1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8) of the 2030 Agenda aims to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all” [

1]. It encompasses three interconnected dimensions: economic growth, employment and decent work, and entrepreneurship [

2,

3]. Achieving these targets—particularly 8.1 (GDP per capita growth), 8.3 (support for micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises), 8.5 (full and productive employment and equal pay), and 8.8 (protection of labor rights and safe work environments)—requires macroeconomic and institutional policies that integrate growth with social inclusion [

4,

5].

In recent years, the international context has revealed persistent vulnerabilities that directly affect SDG 8 outcomes. Global economic growth has slowed amid inflationary pressures, geopolitical tensions and post-pandemic recovery asymmetries [

6]. Labor markets exhibit heterogeneous progress: while unemployment has decreased in several high-income economies, informal employment remains the dominant labor condition in most low- and middle-income regions, exposing workers to precarious income, limited social protection and discriminatory practices [

7,

8]. Entrepreneurship has expanded worldwide, yet barriers to credit, high transaction costs and weak institutional support hinder business consolidation, particularly among small-scale enterprises [

9].

Latin America and the Caribbean face structural challenges to advancing SDG 8. Economic growth remains volatile and highly dependent on commodity cycles; labor markets continue to be segmented; and informality affects nearly half of the workforce, limiting access to social protection and decent work [

10]. In Peru, these patterns are even more pronounced: regional inequality persists, employment quality shows slow improvement, and public investment plays a disproportionate role in generating short-term dynamism rather than structural transformation [

11].

Within this national context, the province of Alto Amazonas—located in the Loreto region of the Peruvian Amazon—presents complex barriers to achieving SDG 8. More than 80% of its workforce is informal, productive activities are concentrated in low-value primary sectors, and entrepreneurial initiatives encounter limited credit access, bureaucratic burdens and insufficient institutional coordination [

12,

13,

14]. At the same time, the province exhibits a strong entrepreneurial spirit and a favorable demographic structure that offers potential for inclusive economic expansion if supported by coherent territorial policies.

Despite its strategic importance, Alto Amazonas remains underrepresented in academic and policy-oriented research on SDG 8. Existing studies focus predominantly on metropolitan areas or the coastal and Andean regions, leaving significant knowledge gaps regarding labor conditions, economic diversification and entrepreneurship in Amazonian provinces. There is also limited evidence on how local institutional dynamics—such as municipal investment, labor oversight capacity and business support services—shape SDG 8 performance in dispersed, riverine territories.

Addressing these gaps, this study analyses the progress and challenges associated with achieving SDG 8 in Alto Amazonas using a mixed-methods approach that integrates quantitative, qualitative and documentary evidence. Accordingly, the following research questions guide the study:

RQ1. What is the perceived level of achievement of SDG 8 in Alto Amazonas in terms of economic growth, employment quality and entrepreneurship?

RQ2. How does SDG 8 performance vary across the five districts of the province?

RQ3. Which territorial and institutional factors help explain the gaps and challenges in attaining SDG 8?

Based on these questions, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1. The overall level of achievement of SDG 8 in the province of Alto Amazonas is at least moderate.

To address these questions, the article is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical and empirical literature on SDG 8;

Section 3 explains the mixed-methods design;

Section 4 reports the quantitative and qualitative results;

Section 5 discusses the findings in light of national and international evidence; and

Section 6 provides the conclusions and policy implications.

2. Literature Review

SDG 8 is grounded in the notion that economic growth must be accompanied by productive employment, labor rights, and opportunities for entrepreneurship in order to generate equitable and sustainable development [

15,

16]. International evidence shows that growth alone does not guarantee improvements in employment quality or income distribution. In many regions—particularly in low- and middle-income countries—productivity remains stagnant, labor markets are segmented, and informal employment persists as a dominant occupational pattern [

17,

18]. These structural weaknesses limit the capacity of national economies to translate growth into decent work and social protection.

In Africa and Asia, several studies highlight the coexistence of economic expansion with limited formalization, weak labor institutions, and high vulnerability among self-employed workers [

19,

20]. Research from Southeast Asia emphasizes the difficulty of integrating micro- and small enterprises into value chains due to credit restrictions, high transaction costs, and regulatory burdens [

21]. Similarly, evidence from North Africa shows that informal workers face persistent barriers to accessing social protection and financial services, which reduces their capacity to accumulate assets and increases their exposure to shocks [

22].

In Latin America and the Caribbean, the literature consistently identifies three challenges to SDG 8: (a) the volatility of growth linked to commodity dependence; (b) structural informality affecting nearly half of the labor force; and (c) limited productive diversification, which restricts formal employment creation [

23,

24,

25]. Although several countries have implemented policies to promote micro-enterprise development and entrepreneurship, empirical studies show that institutional weaknesses—such as credit rationing, limited technical assistance, and bureaucratic complexity—continue to hinder business consolidation [

26]. For example, recent evidence from Paraguay links innovation-oriented entrepreneurship with local productive development dynamics [

27]. Evidence-based syntheses also stress that integrated packages combining skills development, support to MSMEs, and labor market institutions tend to be more effective in improving decent work outcomes in developing contexts [

28].

In the Peruvian context, academic and technical reports reveal that labor informality exceeds 70%, with significant territorial disparities [

29]. Employment quality tends to stagnate in regions with limited infrastructure and low private investment, where public spending becomes the primary driver of economic activity [

30,

31]. Research has documented persistent gaps in labor rights enforcement, gender inequalities in employment, and precarious conditions among rural and Amazonian workers [

32,

33]. At the same time, Peru exhibits a strong entrepreneurial culture; however, business survival rates remain low due to insufficient access to credit, informality-related barriers, and scarce institutional support for small producers [

34].

Despite advances in national-level studies, there is limited empirical evidence on SDG 8 performance in Amazonian territories, particularly at the provincial scale. Existing research focuses on macro-level indicators or urban labor markets, leaving significant knowledge gaps regarding territorial inequalities, local institutional dynamics, and the specific barriers faced by rural and semi-urban workers in dispersed Amazonian environments [

35]. Few studies analyze how decent work, economic growth, and entrepreneurship interact in provinces characterized by high informality, limited connectivity, weak market integration, and strong dependence on public investment.

This literature demonstrates the need for subnational analyses that incorporate territorial, social, and institutional characteristics in order to better understand the pathways and barriers to achieving SDG 8. The present study contributes to this agenda by examining the province of Alto Amazonas, a region that has been largely overlooked in SDG 8 research despite its structural vulnerabilities and its strategic relevance to sustainable development in the Peruvian Amazon [

36,

37,

38,

39].

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods design integrating quantitative, qualitative and documentary components in order to examine the achievement of SDG 8 in the province of Alto Amazonas. The mixed approach was chosen because the complexity of labor dynamics, territorial inequalities and institutional conditions in Amazonian regions cannot be captured adequately through a single methodological perspective [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The design follows a sequential structure in which the quantitative phase provides measurable indicators of economic growth, employment quality and entrepreneurship, while the qualitative phase adds interpretive depth regarding institutional and territorial barriers.

3.1. Study Area

The research was conducted in the province of Alto Amazonas, located in the Loreto region of the Peruvian Amazon. The province comprises five districts—Yurimaguas, Lagunas, Santa Cruz, Teniente César López and Balsapuerto—which present dispersed rural–urban settlement patterns, limited connectivity, and strong dependence on public investment for economic activity. These characteristics shape labor conditions, entrepreneurial opportunities, and access to social protection, making Alto Amazonas a relevant case for analyzing SDG 8 performance in Amazonian territories.

3.2. Population and Sample

The sample included an equal proportion of men and women (50.0% each). Most respondents were adults between 25 and 59 years old (70.0%), followed by young adults aged 18–24 years (15.0%) and older adults aged 60 years and over (15.0%). In geographical terms, the majority resided in Yurimaguas (70.0%), while the remaining districts showed smaller proportions: Balsapuerto (10.0%), Lagunas (10.0%), Teniente César López Rojas (4.0%), Jeberos (3.0%), and Santa Cruz (3.0%). These patterns are aligned with the population structure reported for the Loreto region.

Table 1 presents the educational attainment of the economically active population surveyed, highlighting the predominance of basic education over higher education.

3.3. Survey Instrument and Reliability Analysis

The quantitative phase used a structured questionnaire composed of 22 Likert-type items organized into three analytical dimensions: economic growth, employment and decent work, and entrepreneurship. The scale was validated through expert judgment, and internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.82), indicating good reliability. Convergent validity was examined through item–dimension correlations, all of which were statistically significant.

Table 2 summarizes the analytical dimensions, number of items, SDG 8 targets and main focus areas used in the construction of the indicators.

3.4. Qualitative Component

The qualitative phase consisted of semi-structured interviews with local authorities, mayors of the province of Alto Amazonas and the representative of the Chamber of Commerce. The participants were selected through intentional sampling to guarantee the greatest representativeness of the district municipalities. The interviews were transcribed verbatim. A thematic analysis was performed following three coding stages: open coding (generation of initial categories), axial coding (identification of links between categories) and selective coding (emergence of thematic patterns). This process allowed us to identify recurring meanings related to the perception of economic growth, employment and entrepreneurship.

3.5. Data Analysis

All survey responses were coded on a 1–5 Likert scale. Cases with less than 20% missing data were imputed using the item mean. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (p < 0.05) indicated non-normal distributions; therefore, non-parametric methods were applied. Descriptive statistics included frequency distributions, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) for each item.

Given the ordinal structure of the data, the following tests were used:

H0stat: The median of the SDG 8 Composite Index (IC-ODS8) is less than or equal to 3.00.

H1stat: The median of the SDG 8 Composite Index (IC-ODS8) is greater than 3.00.

Significant differences were analyzed using Dunn–Bonferroni pairwise tests.

The IC-SDG8 was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the dimension scores.

Compliance levels were classified as:

Low: 1.00–2.99

Moderate: 3.00–3.99

High: 4.00–5.00

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The study followed ethical standards approved by the Research Committee of the National Autonomous University of Alto Amazonas. Participation was voluntary, informed consent was obtained in writing, and anonymity was preserved throughout data processing and analysis.

4. Results

The integrated analysis of quantitative, qualitative, and documentary data demonstrates both progress and persistent challenges in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth) in the province of Alto Amazonas. Findings reveal that the local economy remains dependent on public investment, employment is perceived as dignified but unstable, and entrepreneurship is dynamic yet weakly formalized.

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Economic Growth (Items 1–8)

The first analytical dimension, Economic Growth, evaluates perceptions related to household income, consumption, local economic performance, public investment and the participation of the private sector.

Table 3 presents the distribution of responses for the eight items that compose this dimension.

Interpretation: Items 1 and 2 show that more than 60% of respondents agree or strongly agree that their personal income and family consumption have increased over the last year. In contrast, items 4, 5 and 6 show higher proportions of disagreement and midscale responses, suggesting concerns regarding employment stability, opportunities for new businesses and the limited presence of the private sector. Items 7 and 8 register the highest agreement levels, indicating that public investment and social projects are perceived as the main drivers of local economic improvement. Overall, the results confirm that perceptions of economic growth remain strongly linked to public spending, reflecting a still limited diversification of productive activity in Alto Amazonas.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of agreement levels for the economic growth indicators.

Interpretation (

Figure 1): The stacked bars show that, for most items, agreement clearly outweighs disagreement, especially in the perception of public investment and social projects (I7–I8). However, the relatively higher share of disagreement in employment stability and private-sector participation (I4 and I6) reinforces the conclusion that economic growth in Alto Amazonas is perceived as highly dependent on the public sector and only weakly supported by private productive activity.

4.1.2. Employment and Decent Work (Items 9–14)

Table 4 reports the response distribution for items related to employment quality and decent work. Most respondents perceive their jobs as decent and dignified, but indicators linked to labor rights, social protection and social dialogue reveal significant shortcomings.

The results show high agreement levels for decent employment (item 9) and dignified work (item 11), which exceed 85%. However, items 12, 13 and 14 record considerably higher proportions of disagreement and midscale responses, reflecting persistent concerns about labor rights, social protection and workplace dialogue. These patterns suggest that, although most respondents perceive their work as decent and dignified, structural deficits in formal labor conditions remain. The contrast between positive perceptions of job dignity and negative assessments of institutional protection highlights the coexistence of subjective satisfaction and objective precariousness in the labor market of Alto Amazonas.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of agreement levels for the six indicators that assess employment quality and decent work.

The figure shows that decent employment (item 9) and dignified work (item 11) have the highest levels of agreement, exceeding 85%, reflecting strong subjective satisfaction with work conditions. In contrast, indicators related to labor rights (item 12), social protection (item 13) and workplace dialogue (item 14) show substantially lower agreement levels and higher disagreement proportions. These results indicate that while workers perceive their jobs as decent and dignified, the institutional components of decent work—rights, protection and dialogue—remain weak. This reinforces the duality observed in

Table 4: positive perceptions coexist with structural deficits in formal labor conditions across Alto Amazonas.

4.1.3. Entrepreneurship (Items 15–22)

Table 5 presents the distribution of responses for the entrepreneurship items. The results show a strong willingness to undertake entrepreneurial activities, but also significant barriers to business creation, formalization and consolidation.

The results indicate that entrepreneurial intention (item 15) shows the highest agreement levels, with nearly 70% of respondents expressing willingness to start a business. However, items related to financing (item 17), formalization (item 18) and technical assistance (item 20) show higher proportions of disagreement and midscale responses, suggesting the existence of structural barriers that hinder business consolidation. Municipal support (item 19) and innovation (item 21) also show moderate agreement levels, reflecting irregular access to institutional and technical resources. Overall, the data reveal an entrepreneurial ecosystem driven largely by necessity rather than opportunity, consistent with the limited formal employment options in Alto Amazonas.

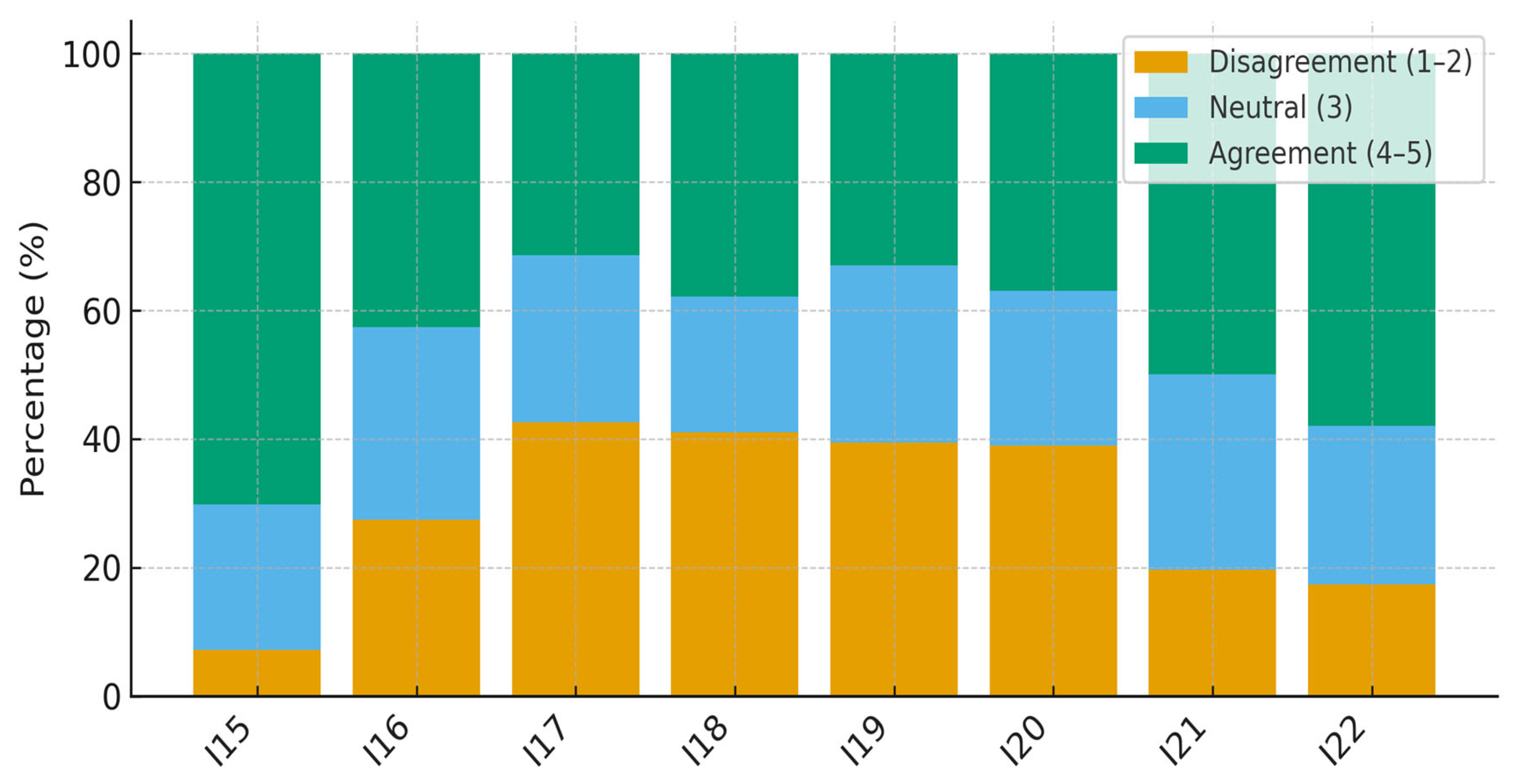

Figure 3 displays the distribution of responses for the entrepreneurship indicators, highlighting patterns related to intention, financing, formalization and business support.

The figure shows that entrepreneurial intention (I15) and perceived contribution to local employment (I22) register the highest levels of agreement, indicating strong motivation among respondents to engage in entrepreneurial activities. In contrast, items related to access to credit (I17), business formalization (I18) and technical assistance (I20) present higher levels of disagreement or neutrality, reflecting persistent structural barriers that limit the viability and growth of new businesses. Municipal support (I19) and innovation (I21) exhibit intermediate patterns, suggesting irregular institutional backing and limited access to specialized services. Overall, the figure reinforces the interpretation that entrepreneurship in Alto Amazonas tends to operate as a survival strategy in a context of scarce formal employment opportunities and weak institutional support.

4.1.4. Inter-Dimensional Relationships

Beyond the item-level findings, the relationships among the three SDG 8 dimensions were examined using Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients. Economic growth, employment and entrepreneurship show moderate, positive and statistically significant associations, indicating that territorial performance is multidimensional rather than fragmented.

Table 6 presents the correlations among the three analytical dimensions of SDG 8 as evidence of internal consistency.

Interpretation (

Table 6): The correlations show that territories with higher perceived economic growth also tend to exhibit better employment conditions and stronger entrepreneurial activity. The strongest association is observed between employment and entrepreneurship (ρ = 0.472), suggesting that improvements in job quality and formality are closely linked to the ability of local actors to create and sustain businesses. Although the coefficients are moderate rather than high, they validate the internal coherence of the SDG 8 Compliance Index and confirm that the three dimensions reinforce one another.

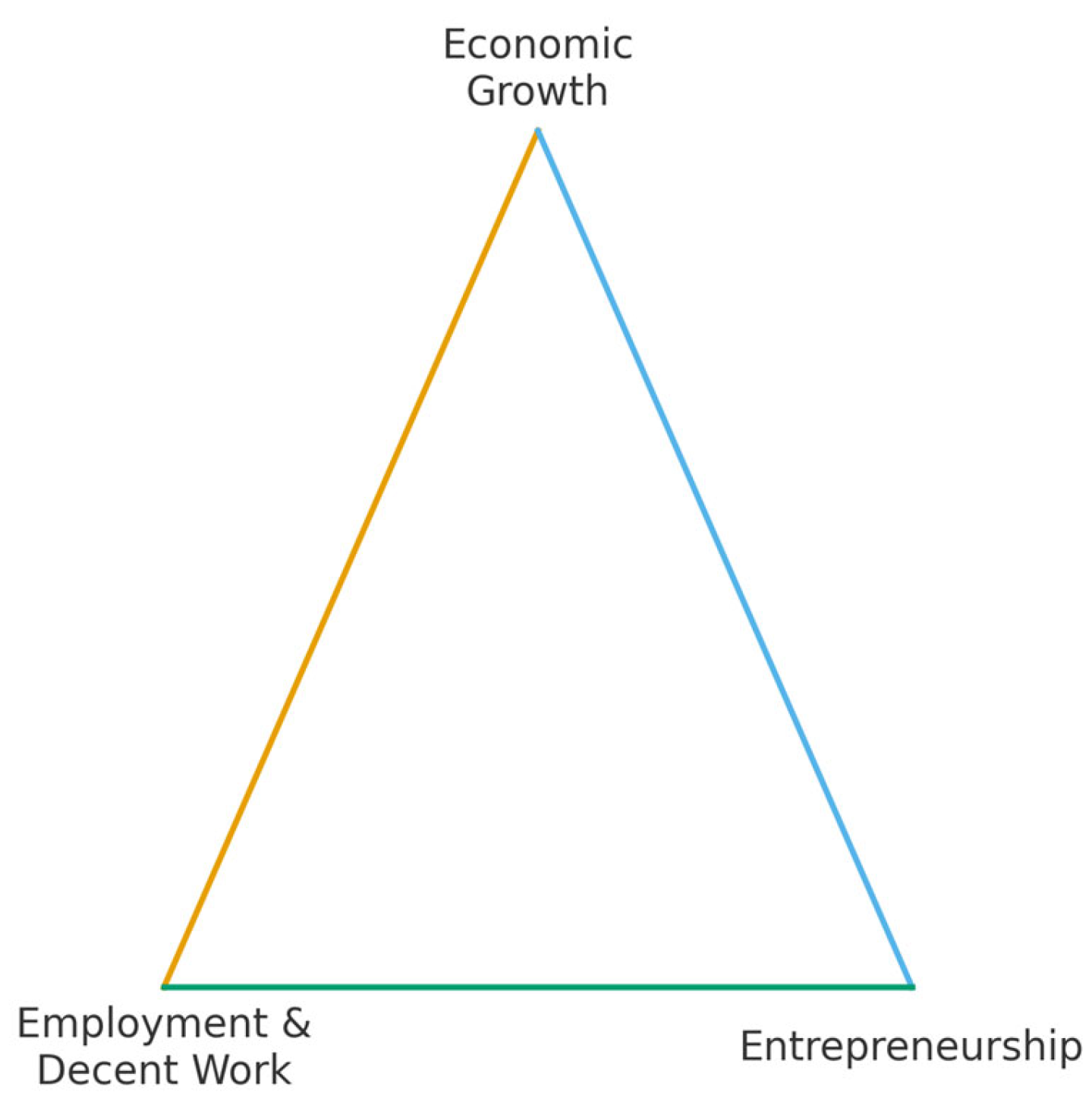

Figure 4 provides a conceptual representation of the interdependence among the three SDG 8 dimensions.

The diagram highlights the interdependence among economic growth, decent work and entrepreneurship. Imbalances in any dimension—such as economic growth without formalization or entrepreneurship without institutional support—can undermine overall progress toward SDG 8.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis H1 was formulated as follows:

H1. The level of achievement of SDG 8 in the province of Alto Amazonas is at least moderate.

To test this hypothesis, the SDG 8 Compliance Index (IC-SDG8) was compared with the neutral benchmark value of 3.00 using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The test produced a statistically significant result (p < 0.01), indicating that the median IC-SDG8 score is higher than the neutral threshold. Approximately 80% of the sample presented scores equal to or greater than 3.00, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 77% to 83%.

In addition, territorial differences were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis H test. The results showed significant variation in IC-SDG8 across the five districts (p < 0.05). Post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni comparisons revealed that Yurimaguas and Teniente César López obtain significantly higher scores than Lagunas and Jeberos, while Santa Cruz represents an intermediate situation.

Table 7 summarizes the non-parametric tests applied to the SDG 8 Compliance Index (IC-SDG8).

Interpretation (Hypothesis testing):

Table 7, the combined evidence confirms H

1. SDG 8 achievement in Alto Amazonas can be characterized as moderate to high at the provincial level, but with marked spatial inequalities. Urban districts with greater access to infrastructure and services outperform rural districts, which remain constrained by informality, limited diversification and weaker institutional capacity.

4.3. Qualitative and Triangulated Findings

The qualitative component of the study included semi-structured interviews with local authorities, mayors of the province of Alto Amazonas and the representative of the Chamber of Commerce. The thematic analysis identified four dominant themes: (i) dependence on public investment, (ii) persistence of informality, (iii) entrepreneurship as a survival strategy and (iv) institutional fragility within the three dimensions.

Table 8 details the construction of the SDG 8 Compliance Index (IC-SDG8) used in the analysis.

The qualitative evidence reinforces the quantitative results by showing that, even when income and employment indicators improve temporarily, the underlying structures of informality and institutional weakness remain largely unchanged. Public investment stimulates short-term economic activity, but these gains do not necessarily translate into sustained improvements in decent work or entrepreneurial consolidation.

Figure 5 provides a schematic overview of the triangulation process, illustrating how quantitative, qualitative and documentary evidence converge in the interpretation of SDG 8 performance.

The diagram shows that a robust assessment of SDG 8 requires integrating multiple sources of information. Survey data offer measurable indicators, qualitative interviews contribute contextualized perceptions and lived experiences, and documentary sources provide macro- and meso-level benchmarks. The convergence of these three components strengthens the credibility, depth and internal coherence of the study’s findings.

4.4. Documentary Analysis

Documentary sources provide essential macro- and meso-economic context for interpreting the results obtained in Alto Amazonas. To contextualize the survey and interview findings,

Table 9 summarizes the main documentary indicators related to SDG 8 at the national, regional, and local levels. According to the INEI report *Perú: Comportamiento de los Indicadores del Mercado Laboral a Nivel Nacional*, the national informal employment rate reached 71.1% in 2023, and INEI indicates that “seven out of ten workers remain in informal employment, mainly in commerce and agricultural activities” [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. Although disaggregated figures are not available specifically for Alto Amazonas, the labor structure of the Loreto region exhibits similar patterns, as shown in INEI’s Regional Employment Statistics [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Macroeconomic trends related to economic growth, fiscal transfers, and public investment dynamics are further documented in official reports from the BCRP and MEF [

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60].

Documentary sources provide essential macro- and meso-economic context for interpreting the results obtained in Alto Amazonas. According to the INEI report Perú: Comportamiento de los Indicadores del Mercado Laboral a nivel Nacional, the national informal employment rate reached 71.1% in 2023, and INEI reports that “seven out of ten workers remain in informal employment, mainly in commerce and agricultural activities” [

45]. Although disaggregated figures are not available specifically for Alto Amazonas, the labor structure of the Loreto region shows similar patterns: INEI’s 2019 Regional Employment Report indicates that only 20.8% of the economically active population in Loreto holds a formal job [

50]. The report also notes that “formalization in Loreto progresses slowly because employment is concentrated in retail trade, family farming, and informal transport services” [

50]. These findings are consistent with the survey results, which reveal weak job stability and limited access to labor rights and social protection.

At the macroeconomic level, the Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (BCRP) reported in its 2024 Annual Report that national GDP contracted –0.4% in 2023, following moderate growth in 2022 [

54]. Formal employment increased by only 0.3%, highlighting the structural fragility of the Peruvian labor market. These results align with the observation that economic expansion has not translated into improvements in employment quality or reductions in informality—key objectives of SDG 8.

With respect to subnational public finance, the Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas (MEF) confirms that the Fondo de Compensación Municipal (FONCOMUN) constitutes the main source of income for district municipalities, often exceeding 70% of local budgets [

55]. This heavy dependency limits fiscal autonomy and reduces the capacity to promote productive diversification. For Alto Amazonas, this means that public spending remains the predominant engine of economic activity, while opportunities to attract private investment or generate sustainable employment remain structurally constrained.

Taken together, these documentary findings reveal a convergent pattern:

- (1)

strong dependence on public investment as the main driver of economic activity,

- (2)

persistent labor informality at national and regional levels, and

- (3)

an entrepreneurial model that is reactive—based on subsistence and necessity—rather than transformative or innovation-driven.

These insights are fully consistent with the survey and interview data, confirming that Alto Amazonas faces structural and institutional constraints in progressing toward SDG 8.

4.5. Triangulation of Findings

Triangulation of quantitative, qualitative and documentary evidence provides a coherent and multidimensional understanding of SDG 8 performance in Alto Amazonas. At the quantitative level, 62% of respondents perceived improvements in household income over the previous year, and 68% attributed this growth primarily to public investment. However, only 54% reported stable employment, and just 30% had access to any form of social protection. The SDG 8 Compliance Index reached 63%, but with marked territorial disparities: Yurimaguas and Teniente César López exceeded 70%, while Lagunas and Jeberos remained below 60%, reflecting unequal access to infrastructure and urban services.

Qualitative interviews reinforced these tendencies. Local authorities acknowledged that job creation depends largely on public works financed through FONCOMUN, while entrepreneurs highlighted persistent obstacles to formalization and credit access, including bureaucratic delays, high interest rates and lack of technical assistance. Many participants described entrepreneurship as a “survival strategy rather than a development model,” underscoring the precarious nature of self-employment in the absence of robust private-sector ecosystems.

Documentary evidence confirmed the structural conditions underlying these perceptions. INEI and BCRP report that national GDP contracted −0.4%, labor informality remains above 70%, and formal employment is particularly limited in Amazonian regions [

45,

50,

54]. MEF data show that more than 70% of municipal budgets depend on FONCOMUN transfers, constraining fiscal autonomy and limiting the territory’s ability to promote productive diversification [

55]. These findings align with survey and interview evidence, confirming that economic activity and job creation rely heavily on public expenditure, while opportunities for sustained, privately driven growth remain limited.

Minor divergences also emerged. Although 88% of survey respondents described their work as “decent” and 93% as “dignified,” qualitative accounts revealed that these descriptors often reflect aspirational or normative perceptions rather than actual fulfillment of labor standards. Likewise, while respondents associated economic improvement with public projects, documentary sources indicate that such initiatives frequently lack continuity once funding cycles end.

Overall, triangulation confirms that Alto Amazonas advances toward SDG 8 through public-led growth but remains constrained by chronic informality, fiscal dependence and institutional fragility. The convergence between survey indicators, interview narratives and official statistics strengthens the internal validity of the mixed-methods approach and provides a solid foundation for the analytical arguments developed in the Discussion.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a multidimensional scenario in which Alto Amazonas exhibits partial progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 8, yet continues to face persistent structural barriers that limit sustainable and inclusive economic development. The coexistence of moderate economic dynamism, precarious labor structures, and weakly consolidated entrepreneurship aligns with regional and global evidence showing that economic growth alone does not guarantee improvements in employment quality or reductions in informality [

17,

18,

19,

20].

First, the results demonstrate that local economic dynamism is driven primarily by public investment rather than private-sector activity. This confirms what Latin American studies have long documented regarding the volatility of growth in territories dependent on public expenditure and commodity cycles [

23,

24]. The strong association between improvements in household income and public investment underscores the fiscal vulnerability of Alto Amazonas, where municipal budgets depend disproportionately on FONCOMUN transfers, as reported by MEF and BCRP. These macro- and meso-economic patterns indicate that the province’s economic expansion is not yet accompanied by productive diversification—one of the core principles underlying SDG 8.

Second, although most respondents described their work as “decent” and “dignified,” the quantitative and qualitative evidence exposes a structural deficit in labor rights, social protection and employment stability. This apparent contradiction between perceived dignity and factual precariousness is consistent with research showing that job satisfaction in informal economies often reflects adaptive expectations shaped by limited opportunities rather than actual fulfillment of labor standards [

18,

22]. The strong negative correlation between dignified work and lack of labor rights (ρ = −0.48;

p < 0.01) empirically confirms this dynamic. Territorial disparities further deepen the issue: urban districts such as Yurimaguas and Teniente César López concentrate the most favorable conditions, while Lagunas and Jeberos remain entrenched in structural informality, weak institutional oversight and limited social protection. These findings echo national reports showing that informality exceeds 70% in Peru and reaches its highest levels in the Amazon region [

30,

32,

33].

Third, entrepreneurship emerges as both a significant aspiration and a constrained reality. While nearly 70% of participants expressed intentions to start a business, fewer than 40% managed to formalize one, and only 18.6% accessed formal credit. These outcomes are consistent with evidence from Southeast Asia and Latin America indicating that micro-entrepreneurial activity often operates as a survival strategy in contexts with limited formal employment, high transaction costs and barriers to accessing finance [

21,

26]. The obstacles identified—lack of capital, bureaucratic hurdles and insufficient technical assistance—reflect the institutional weaknesses characteristic of Amazonian and rural economies, where entrepreneurial ecosystems lack the infrastructure, financing mechanisms and regulatory stability needed for sustained growth.

Fourth, the moderate correlations found among the three SDG 8 dimensions (ρ = 0.39–0.47) reveal internal coherence within the SDG 8 Compliance Index and support the notion that economic growth, decent work and entrepreneurship are interdependent. This is consistent with international evidence showing that progress in any single SDG 8 component reinforces the others when supported by adequate institutional frameworks [

15,

16]. However, the relatively modest strength of these associations indicates that, in Alto Amazonas, the synergy among the three dimensions remains weak, largely due to territorial fragmentation and limited institutional coordination.

Finally, the triangulation of quantitative, qualitative and documentary evidence confirms that Alto Amazonas maintains an active yet structurally fragile economy. Interviewees consistently described an environment where public investment generates short-term employment, entrepreneurship compensates for labor precariousness and local development policies lack continuity due to political turnover. These findings mirror broader national and regional analyses highlighting institutional volatility, uneven territorial development and chronic informality as systemic barriers to SDG 8 in the Peruvian Amazon [

10,

11,

34].

Overall, the study demonstrates that achieving SDG 8 in Alto Amazonas requires more than economic growth: it demands an integrated agenda that promotes formalization, labor rights enforcement, productive diversification, financial inclusion and institutional strengthening. Without addressing these structural constraints, economic dynamism will remain dependent on public investment, labor will continue to be precarious and entrepreneurship will persist as a subsistence strategy rather than a driver of sustainable development.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence and theoretical insight into the progress and limitations of Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8) in the province of Alto Amazonas, Peru. Using a mixed-methods design that integrated quantitative surveys, qualitative interviews and documentary analysis, the research identified partial advances toward decent work and economic growth, alongside persistent structural constraints related to informality, fiscal dependence and limited institutional capacity.

The results show that economic dynamism in Alto Amazonas is largely driven by public investment, generating short-term improvements in household income but insufficient progress in employment quality or labor formalization. Although 62% of respondents perceived an increase in income and 88% described their work as “dignified,” only 30% reported access to social protection. Interview findings further revealed that both entrepreneurship and public employment operate primarily as mechanisms of survival rather than as engines of productive development. Documentary evidence from MEF, BCRP and INEI corroborates this structural dependency, highlighting the restricted fiscal autonomy of local governments and the persistence of informal labor structures.

From a policy perspective, three strategic priorities emerge. First, productive diversification is essential to reduce dependence on public investment and stimulate the creation of quality employment, particularly in sectors aligned with green and community-based development. Second, labor formalization and protection require coordinated action among local authorities, labor inspection systems and social-security mechanisms to extend decent work to rural and informal workers. Third, strengthening entrepreneurial ecosystems demands integrated efforts in technical assistance, training, and access to credit, framed within a territorial model that promotes innovation, inclusion and sustainability.

The study also underscores the importance of higher-education institutions—particularly the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Alto Amazonas—as key mediators of knowledge, innovation and territorial development. Strengthening university research, extension and collaboration with local governments can enhance capacity-building, promote evidence-based decision-making and increase accountability in SDG 8 implementation.

Methodologically, the triangulation of quantitative, qualitative and documentary evidence validated the internal coherence of perceptions, institutional reports and official indicators. This demonstrates that mixed-methods approaches are not only feasible but necessary to territorialize SDG 8 and understand its subnational dynamics—an analytical contribution that can be applied to other Amazonian and peripheral regions.

This study has several limitations. The use of a non-probabilistic sampling strategy restricts the statistical generalization of findings to the broader population of Alto Amazonas. The cross-sectional design captures labor conditions at a single point in time and may be influenced by short-term shocks. Some indicators rely on self-reported information, which can be affected by recall bias or social desirability. Furthermore, the study focuses on a single Amazonian province; therefore, future research should compare these patterns across other regions of Peru and Latin America to deepen the understanding of territorial disparities in SDG 8.

In conclusion, advancing SDG 8 in Alto Amazonas requires simultaneous progress across three interdependent dimensions: (i) environmentally responsible economic diversification, (ii) institutional strengthening for labor protection and social security, and (iii) inclusive and innovative entrepreneurship supported by education and local capacity-building. Addressing these interconnected dimensions is essential for transforming economic growth into sustainable human development and for moving the region toward a more just, resilient and equitable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, W.D.-P.; validation, experts in research instruments and economists; data curation and formal analysis, R.Z.-E.; fieldwork and interviews, M.R.R.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.-C.; writing—review and English editing, C.E.R.-C.; visualization, supervision, project management advice and funding acquisition, Research Institute of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Alto Amazonas (UNAAA). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Alto Amazonas (UNAAA), Loreto, Peru. The university approved the guidelines of the public competition for project selection through Resolution No. 246-2023-UNAAA/CO (2 June 2023). Subsequently, Presidential Resolution No. 245-2023-UNAAA/P (13 July 2023) authorized the funding of the project “Level of SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth in the Jurisdiction of Alto Amazonas”, from which this article is derived. The APC was also funded by UNAAA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The National Autonomous University of Alto Amazonas (UNAAA) exempted this study from ethical review and approval in accordance with its internal regulations (General Research Regulations, Organizing Committee Resolution No. 035-2021-UNAAA/CO, the Code of Ethics for Research approved by Organizing Committee Resolution No. 136-2023-UNAAA/CO, and the Monitoring and Follow-Up Directive, Resolution No. 079-2022-UNAAA/CO) and national legislation (University Law No. 30220), given that the study involved minimal-risk social research conducted through surveys, without clinical intervention or biological manipulation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1975; revised in 2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals who participated in the survey and from all authorities involved in the interviews.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study—including anonymized survey responses, interview transcripts and secondary sources—are archived at the UNAAA Research Institute. Due to ethical and privacy restrictions, these data are not publicly available but may be requested from the authors under the appropriate institutional procedures. For access inquiries, please contact wdiaz@unaaa.edu.pe.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the UNAAA Research Institute and the Vice Presidency of Research for promoting research funding in the Amazon region. We also thank the citizens and local authorities who indirectly contributed through survey responses and interviews. The authors state that they used the tool ChatGPT (OpenAI 5.2) in a complementary manner for language-enhancement purposes, specifically to improve the clarity, grammar, and cohesion of the manuscript. All conceptual, analytical, and interpretative decisions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UNAAA | Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Alto Amazonas |

| FONCOMUN | Fondo de Compensación Municipal |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| MSMEs | Micro, Small-, and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| INEI | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (Peru) |

| MEF | Ministry of Economy and Finance (Peru) |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

Appendix A. Survey Questionnaire on Sustainable Development Goal 8 (SDG 8)

This appendix presents the full wording of the 22 items used to construct the SDG 8 indicators, grouped into the three analytical dimensions of economic growth, employment quality and entrepreneurship.

| Institution: National Autonomous University of Alto Amazonas |

| Faculty: Faculty of Economic, Administrative and Accounting Sciences |

Instructions:

This questionnaire aims to understand perceptions regarding economic growth, employment, and entrepreneurship among the economically active population of Alto Amazonas. Respondents are asked to read each statement carefully and select only one option according to their level of agreement.

Response scale:

1 = Strongly disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Neutral; 4 = Agree; 5 = Strongly agree. |

Table A1.

Sociodemographic information of respondents.

Table A1.

Sociodemographic information of respondents.

| Variable | Response options |

|---|

| Age | Open response |

| Gender | Male; Female |

| Educational level | No schooling; Incomplete primary; Complete primary; Incomplete secondary; Complete secondary; Incomplete non-university higher education; Complete non-university higher education; Incomplete university education; Complete university education |

| Type of worker | Dependent; Independent |

Table A2.

Questionnaire items by dimension (Likert scale 1–5).

Table A2.

Questionnaire items by dimension (Likert scale 1–5).

| Dimension | Item | Statement |

|---|

| Economic Growth | I1 | Economic growth contributes to your personal well-being. |

| Economic Growth | I2 | You consider that your income increased between 2018 and 2022. |

| Economic Growth | I3 | Your income between 2018 and 2022 allowed you to meet your basic needs (food, clothing, education, health). |

| Economic Growth | I4 | Your income between 2018 and 2022 enabled you to improve your home. |

| Economic Growth | I5 | Your income between 2018 and 2022 allowed you to engage in leisure activities (e.g., national or international travel). |

| Economic Growth | I6 | Your current income provides the necessary means to support your personal development. |

| Economic Growth | I7 | Your income is reflected in the salary and/or wages you receive. |

| Economic Growth | I8 | Your income is also reflected through tips, piecework payments, or payments in kind. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I9 | You consider your employment to be decent compared to work conditions in Alto Amazonas. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I10 | You have experienced discrimination (race, gender, religion, etc.) while applying for a job. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I11 | You consider your work to be dignified. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I12 | Your employment is carried out without respect for fundamental labor rights. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I13 | Your employment is carried out without social protection. |

| Employment and Decent Work | I14 | Social dialogue is absent in your workplace. |

| Entrepreneurship | I15 | You have considered becoming your own boss. |

| Entrepreneurship | I16 | You developed entrepreneurial ideas between 2018 and 2022. |

| Entrepreneurship | I17 | You started a business between 2018 and 2022. |

| Entrepreneurship | I18 | You solved financial difficulties thanks to your entrepreneurship between 2018 and 2022. |

| Entrepreneurship | I19 | Entrepreneurial ventures in Alto Amazonas tend to be long-term. |

| Entrepreneurship | I20 | Businesses in the province have formalized their micro and small enterprises (MSEs). |

| Entrepreneurship | I21 | You believe that immigrants in Alto Amazonas tend to be more entrepreneurial. |

| Entrepreneurship | I22 | You consider your family or close environment to be entrepreneurial. |

Appendix B. List of Editorial Annotations and Correspondence with Reviewers (Second Round)

| Code | Reviewer/Comment | Location in Manuscript | Description of Modification Implemented |

| R2–C1 | Reviewer 2—Comment 1 | Section 2, Page 4 | Main hypothesis rewritten; three sub-hypotheses added; hypotheses moved earlier in the manuscript. |

| R2–C5 | Reviewer 2—Comment 5 | Section 4, Page 13 | Analytical content removed from Results and relocated into Section 5 (Discussion). |

| R2–C4 | Reviewer 2—Comment 4 | Section 5, Pages 14–15 | Expanded methodological justification for econometric analysis and SDG 8 Index construction. |

| R2–C3A | Reviewer 2—Comment 3 | Appendix A, Pages 19–20 | Full 22-item survey instrument added in Spanish and English. |

| R2–C3B | Reviewer 2—Comment 3 | Appendix B, Pages 21–22 | Extended anonymized interview excerpts and full guide added. |

| R2–C2 | Reviewer 2—Comment 2 | Table 1, Page 6 | Descriptive statistics table (n = 500) clearly presented; text introduction added. |

| R3–C1 | Reviewer 3—Final assessment | — | Reviewer stated: ‘The article can be published.’ No further modifications required. |

| R1–C1 | Reviewer 1—Final assessment | — | Reviewer confirmed all recommendations were addressed. No additional changes required. |

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023_Spanish.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- UN DESA. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- ECLAC. Latin America and the Caribbean Faced with the Challenge of Accelerating Progress towards the 2030 Agenda: Transitions towards Sustainability (LC/FDS.7/3); ECLAC: Santiago, Chile, 2024; Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/69132 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook 2023: Trends; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN DESA. Policy Integration and Institutional Arrangements for the 2030 Agenda; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/policy-integration-2030agenda (accessed on 2 December 2023).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier—Human Development and the Anthropocene; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://files.acquia.undp.org/public/migration/arabstates/hdr_2020_overview_english.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- ECLAC. Decent Work and Economic Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean: Challenges for the 2030 Agenda; ECLAC: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Giles Álvarez, L.; Vargas-Moreno, J.C.; Ávila Aravena, B.; King, C.; Heinle, W. A Green, Inclusive, and Sustainable Development Framework for the Amazon Region; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Jobs Diagnostics: Peru Country Report; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099238405022236711/p1778550b3615b06c0a1b067e70aa76b57b (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Gutiérrez Goiria, J.; Herrera Herrera, A.F. SDG 8: Economic Growth and Its Difficult Place in the 2030 Agenda. Rev. Int. Comun. Desarro. 2021, 3, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, D.; Donovan, J.; Mulder, G.; Monterroso, I.; Guariguata, M.R.; Cronkleton, P.; Albornoz, M.A.; Pacheco, P.; Katila, P.; Gitz, V.; et al. Forest-Dependent Communities and Sustainable Development Goal 8: Inclusive and Green Growth Pathways. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEI. Comportamiento de la Economía Peruana en 2023; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization (ILO). Decent Work; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Gender Equality and Decent Work Statistics 2024; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Riaño Casallas, M.I. Decent Work and Labor Informality in Latin America: Reflections and Analyses for Latin America and the Caribbean; Fundación Carolina: Madrid, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/DT_FC_98.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Ministry of Labor and Employment Promotion (MTPE). Quarterly Labor Market Report: Employment Situation 2024, Quarter I; MTPE: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mtpe/informes-publicaciones/5783668-informe-trimestral-del-mercado-laboral-situacion-del-empleo-en-2024-trimestre-i (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Informality in Peru Fell, but in 10 Cities the Situation Was Different. 14 August 2024. Available online: https://gestion.pe/economia/informalidad-en-peru-cayo-pero-en-10-ciudades-la-situacion-fue-otra-como-entenderlo-empleo-en-peru-puestos-de-trabajo-inei-mercado-laboral-noticia/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Tudela-Mamani, J.W.; Ancasi-Cáceres, G.; Álvarez-Rozas, K. Multidimensional Assessment of Decent Work in the Puno Region: 2013–2017. Rev. Investig. Altoandinas J. High Andean Res. 2020, 22, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Guiza, O.E.; Lozano Martínez, D.R.; Rodríguez Perdomo, D. Is Labor Formalization the Path toward Decent Work in Colombia? Nuevo Derecho 2024, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Brid, J.C.; Gómez Tovar, R.; Sánchez Gómez, J.; Gómez Rodríguez, L. The Automotive and Textile Industries in Mexico: Trade and Decent Work. Trimest. Econ. 2023, 90, 7–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ILO; United Nations. Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development: Policy Brief; ILO/UNDP: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). Global Report 2023/2024; GEM Consortium: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=51377 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Menegaz, J.C.; Trindade, L.L.; Santos, J.L.G. Entrepreneurship in Nursing: Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goal “Health and Well-Being”. Rev. Enferm. UERJ 2021, 29, e61970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recalde Garay, C.N.; Galeano Sánchez, J.A.; Gallego Correa, G. Analysis of the Progress of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the Municipality of Villa Elisa, Central Department, Paraguay; Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences: Warszawa, Poland, 2020; Available online: https://catalogobibliografico.facen.una.py/cgi-bin/koha/opac-ISBDdetail.pl?biblionumber=647 (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Uribe, G.; Cortés, V. Women Entrepreneurs and Gender Gaps in Latin America. CEPAL Rev. 2022, 136, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón, J.; Ramos, D. Youth Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policies in the Peruvian Amazon. Rev. Gestión Soc. 2023, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón-Tovar, J.A.; Ramos-Sarmiento, R.E. Innovation, entrepreneurship and territorial development in Paraguay. Rev. Científ. UDC 2024, 41, 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Office. What Works: Promoting Pathways to Decent Work; International Labor Organization: Geneve, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/%40dgreports/%40inst/documents/publication/wcms_724049.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- PRODUCE (Peru). Annual Report on Micro and Small Enterprises 2024; Ministry of Production: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Banco Central de Reserva del Perú (BCRP). Revista Moneda 201—Peruvian Labor Market: Stylized Facts and Measurement; BCRP: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/docs/Publicaciones/Revista-Moneda/moneda-201/moneda-201-11.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Ávila Aravena, B.; Giles Álvarez, L.; Larrahondo, C.; Vargas-Moreno, J.C. Territorial Framework for Inclusive, Sustainable, and Green Development of the Andean Amazon Region; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas (MEF). Reporte Económico Regional: Loreto 2024; MEF: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Regional Economic Bulletin Loreto 2024; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations DESA. Policy Coherence and SDG Implementation at the Sub-National Level; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/policy-coherence-sdgs-subnational (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Ranieri, R.; Ramos, R.A. Inclusive Growth: Building up a Concept; IPC-IG Working Paper 104; UNDP: Brasília, Brazil, 2013; Available online: https://ipcid.org/sites/default/files/pub/en/IPCWorkingPaper104.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Solow, R.M. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q. J. Econ. 1956, 70, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P.M. Endogenous technological change. J. Polit. Econ. 1990, 98, S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebisch, R. The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1950; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/29973/S5205EN.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Fajnzylber, F. Industrialisation in Latin America: From the “Black Box” to the “Empty Slot”; Cuadernos de la CEPAL No. 60; ECLAC: Santiago, Chile, 1983; Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/2737/060_en.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Bértola, L.; Ocampo, J.A. The Economic Development of Latin America since Independence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe Mallorquín, R.; Sánchez, L. Informal employment and social protection in Latin America. Int. Labor Rev. 2023, 162, 315–339. [Google Scholar]

- Tokman, V.E. Informality in Latin America: Roots, Concepts and Policy Responses; ILO Working Paper No. 160; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Greenwald, B. Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development and Social Progress; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEI. Peru: Behaviour of Labor Market Indicators at the National Level. First Quarter 2023; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Venezia, A.; González-Campa, C.; Santillán, J. Public policies and the territorialisation of SDGs: Lessons from Latin America. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokri, S.; Ben Abdallah, M.; Karray, S. Decent work and economic growth in North Africa: Empirical assessment of SDG 8 indicators. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cripps, A.; Williams, P.; Patel, D. Employment, education and the sustainable development goals: Evaluating local labor initiatives. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2024, 105, 102830. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M. Assessing governance mechanisms for SDG implementation: Evidence from decentralised economies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3124. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. Loreto: Formal Employment in the Region of Loreto, 2019; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2019; Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/4631781/16.%20Loreto.pdf?v=1685552711 (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Horan, D. Universities and the 2030 Agenda: Integrating SDG 8 into regional development strategies. High. Educ. Policy 2023, 36, 893–912. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human Development Report 2023: Breaking the Gridlock; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BCRP. Annual Report 2024: Production and Employment; Banco Central de Reserva del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/eng-docs/Publications/Annual-Reports/2024/annual-report-2024-1.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- MEF. Municipal Compensation Fund (FONCOMUN); Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ECLAC. Sustainable Development in the Latin-American Amazon: Challenges for the 2030 Agenda; United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- UN DESA. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023: Times of Crisis, Times of Change; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023 (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- IDB. Institutional Capacities for the Implementation of SDG 8 in Sub-national Governments; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BCRP. Peru’s Labor Market and Fiscal Policy Report 2024; Banco Central de Reserva del Perú: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://www.bcrp.gob.pe/docs/Publicaciones/Reporte-Laboral-Fiscal-2024.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- INEI. National Household Survey 2024: Employment and Incomes; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática: Lima, Peru, 2024; Available online: https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib2008/libro.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

Figure 1.

Economic growth indicators (Items 1–8).

Figure 1.

Economic growth indicators (Items 1–8).

Figure 2.

Employment and decent work indicators (Items 9–14).

Figure 2.

Employment and decent work indicators (Items 9–14).

Figure 3.

Entrepreneurship indicators (Items 15–22).

Figure 3.

Entrepreneurship indicators (Items 15–22).

Figure 4.

The three dimensions of SDG 8: economic growth (blue line), employment and decent work (orange line), and entrepreneurship (green line).

Figure 4.

The three dimensions of SDG 8: economic growth (blue line), employment and decent work (orange line), and entrepreneurship (green line).

Figure 5.

Triangulation process used in the study, integrating quantitative survey data, qualitative interview findings, and documentary analysis of official data to generate a triangulated interpretation of SDG 8.

Figure 5.

Triangulation process used in the study, integrating quantitative survey data, qualitative interview findings, and documentary analysis of official data to generate a triangulated interpretation of SDG 8.

Table 1.

Educational level of the economically active population surveyed in Alto Amazonas (n = 500).

Table 1.

Educational level of the economically active population surveyed in Alto Amazonas (n = 500).

| Educational Level | n | % |

|---|

| Primary education | 175 | 35.0 |

| Secondary education | 225 | 45.0 |

| Higher education (technical/university) | 100 | 20.0 |

| Total | 500 | 100 |

Table 2.

Dimensions, number of items, SDG 8 target and main focus.

Table 2.

Dimensions, number of items, SDG 8 target and main focus.

| Dimension | Number of Items | SDG 8 Target | Main Focus |

|---|

| Economic Growth | 8 (Items 1–8) | 8.1 | Perception of income, consumption, investment, and public spending |

| Employment and Decent Work | 6 (Items 9–14) | 8.5 and 8.8 | Quality of employment, protection, and labor rights |

| Entrepreneurship | 8 (Items 15–22) | 8.3 | Entrepreneurial intention, formalization, and access to financing |

Table 3.

Distribution of responses on economic growth (Items 1–8, n = 500).

Table 3.

Distribution of responses on economic growth (Items 1–8, n = 500).

| Item | 1 TDA | 2 DA | 3 MEI | 4 ED | 5 TED |

|---|

| 1. Increase in personal income | 4.6 | 10.2 | 23.0 | 44.0 | 18.2 |

| 2. Growth in family consumption | 5.0 | 11.6 | 21.4 | 45.2 | 16.8 |

| 3. Improvement in local economy | 6.8 | 14.0 | 27.2 | 36.0 | 16.0 |

| 4. Employment stability | 8.0 | 16.2 | 25.0 | 34.2 | 16.6 |

| 5. Opportunities for new businesses | 7.6 | 17.0 | 26.4 | 33.0 | 16.0 |

| 6. Private-sector participation | 10.2 | 19.8 | 25.0 | 29.0 | 16.0 |

| 7. Effect of public investment | 3.0 | 7.8 | 20.0 | 43.2 | 26.0 |

| 8. Impact of social projects | 5.0 | 9.4 | 22.0 | 42.6 | 21.0 |

Table 4.

Distribution of responses on employment and decent work (Items 9–14, n = 500).

Table 4.

Distribution of responses on employment and decent work (Items 9–14, n = 500).

| Item | 1 TDA | 2 DA | 3 MEI | 4 ED | 5 TED |

|---|

| 9. Decent employment | 1.2 | 6.8 | 3.6 | 52.0 | 36.4 |

| 10. Discrimination at work | 19.0 | 40.8 | 7.6 | 20.6 | 12.0 |

| 11. Dignified work | 0.8 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 51.4 | 42.2 |

| 12. Lack of labor rights | 16.2 | 33.4 | 13.0 | 29.2 | 8.2 |

| 13. Lack of social protection | 8.0 | 41.2 | 13.6 | 29.0 | 8.2 |

| 14. Absence of social dialogue | 16.0 | 34.0 | 14.8 | 30.2 | 5.0 |

Table 5.

Distribution of responses on entrepreneurship (Items 15–22, n = 500).

Table 5.

Distribution of responses on entrepreneurship (Items 15–22, n = 500).

| Item | 1 TDA | 2 DA | 3 MEI | 4 ED | 5 TED |

|---|

| 15. Entrepreneurial intention | 2.0 | 5.2 | 22.6 | 47.2 | 23.0 |

| 16. Ease of starting a business | 7.0 | 20.4 | 30.0 | 32.0 | 10.6 |

| 17. Access to financing | 15.0 | 27.6 | 26.0 | 21.0 | 10.4 |

| 18. Business formalization | 12.0 | 29.0 | 21.2 | 25.8 | 12.0 |

| 19. Municipal support to entrepreneurs | 11.4 | 28.0 | 27.6 | 24.0 | 9.0 |

| 20. Technical advice availability | 9.0 | 30.0 | 24.0 | 28.0 | 9.0 |

| 21. Innovation in products/services | 4.6 | 15.0 | 30.4 | 35.0 | 15.0 |

| 22. Contribution to local employment | 5.0 | 12.4 | 24.6 | 38.0 | 20.0 |

Table 6.

Spearman correlations among SDG 8 dimensions (n = 500).

Table 6.

Spearman correlations among SDG 8 dimensions (n = 500).

| Variable | Economic Growth | Employment and Decent Work | Entrepreneurship |

|---|

| Economic Growth | — | 0.436 ** | 0.398 * |

| Employment and Decent Work | | — | 0.472 ** |

| Entrepreneurship | | | — |

Table 7.

Summarizes the non-parametric tests applied to the SDG 8 Compliance Index (IC-SDG8).

Table 7.

Summarizes the non-parametric tests applied to the SDG 8 Compliance Index (IC-SDG8).

| Test | Purpose | Null Hypothesis (H0) | Result | Interpretation |

|---|

| Wilcoxon signed-rank | Compare IC-SDG8 median with neutral value (3.00) | Median(IC-SDG8)

≤ 3.00 | p < 0.01 | IC-SDG8 is significantly higher than the neutral level |

| Kruskal–Wallis H | Compare IC-SDG8 distributions among districts | IC-SDG8 is equal across districts | p < 0.05 | There are significant territorial differences |

Table 8.

Themes emerging from qualitative analysis and illustrative insights.

Table 8.

Themes emerging from qualitative analysis and illustrative insights.

| Theme | Description | Illustrative Insight |

|---|

| Dependence on public investment | Local economic activity is driven primarily by public works and short-term programs financed through FONCOMUN. | Interviewees noted that employment peaks during municipal projects and declines once funding ends. |

| Persistence of informality | High prevalence of informal employment with limited enforcement of labor standards and social protection. | Several participants reported working without contracts or insurance, relying on verbal agreements. |

| Entrepreneurship as survival | Entrepreneurial activity emerges mainly as a response to the scarcity of formal jobs rather than as an innovation-driven strategy. | Entrepreneurs described starting small businesses using family savings to compensate for unstable wages. |

| Institutional fragility | Frequent political turnover and weak coordination among government levels hinder continuity of development policies. | Authorities acknowledged difficulties in sustaining training and employment programs beyond a single municipal term. |

Table 9.

Summary of documentary evidence supporting SDG 8 indicators in Alto Amazonas.

Table 9.

Summary of documentary evidence supporting SDG 8 indicators in Alto Amazonas.

| Source | Year | Indicator | Reported Value | Geographic Scope | Relevance to SDG 8 |

|---|

| INEI [45] | 2023 | National informal employment rate | 71.1% | Peru (national) | Target 8.5—Decent work |

| INEI [50] | 2019 | Formal employment rate (Loreto region) | 20.8% | Loreto (regional) | Target 8.5—Productive employment |

| BCRP [54] | 2024 | National GDP growth rate | −0.4% (2023) | Peru (national) | Target 8.1—Economic growth |

| MEF [55] | 2024 | Municipal financing dependency on FONCOMUN | Predominant (>70%) | Local governments | Target 8.1—Fiscal sustainability |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |