Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change in South African Smallholder Systems: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Literature Review

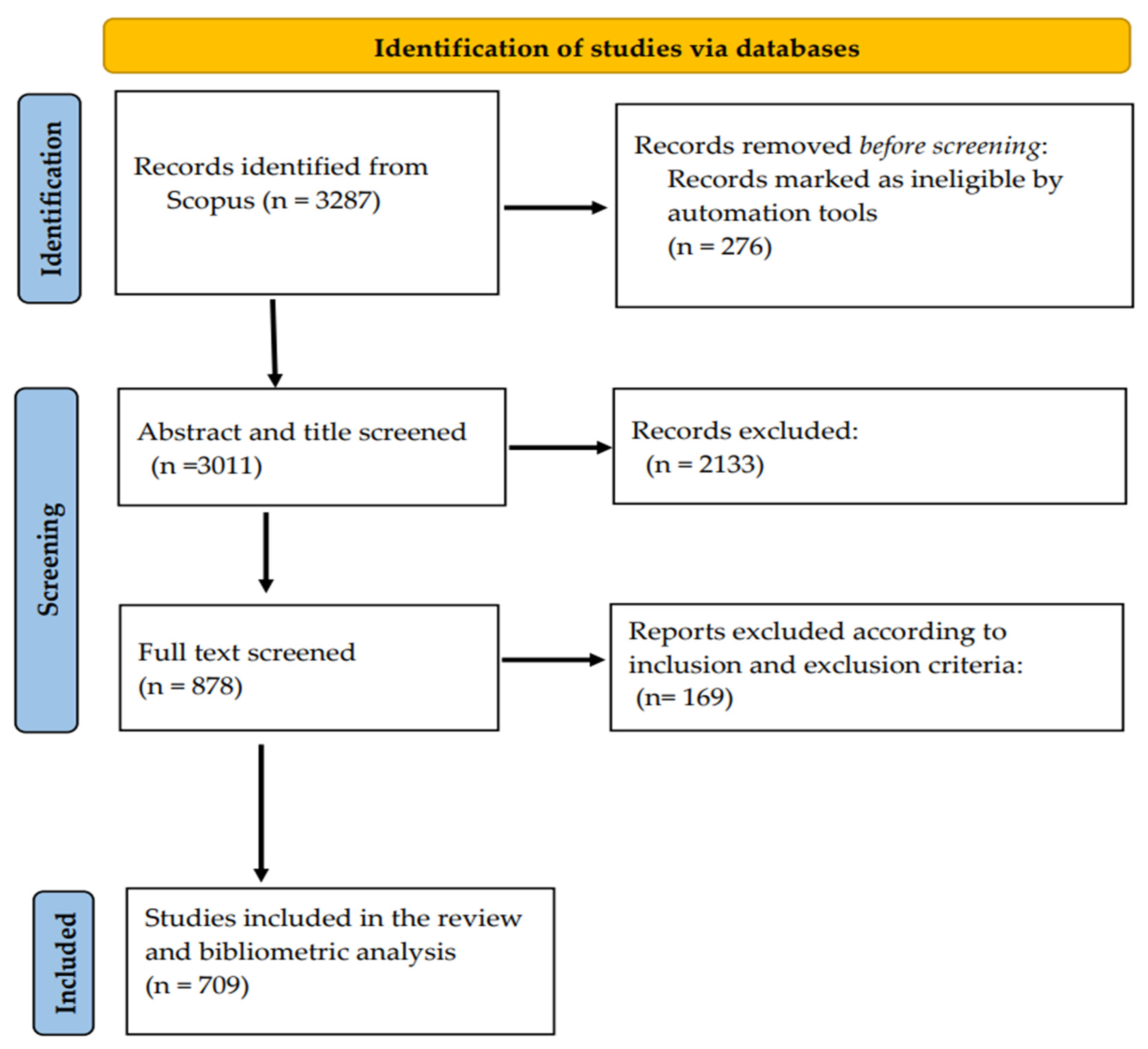

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Identification of Information Sources

3.2. Study Selection Criteria

3.3. Bibliometric Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

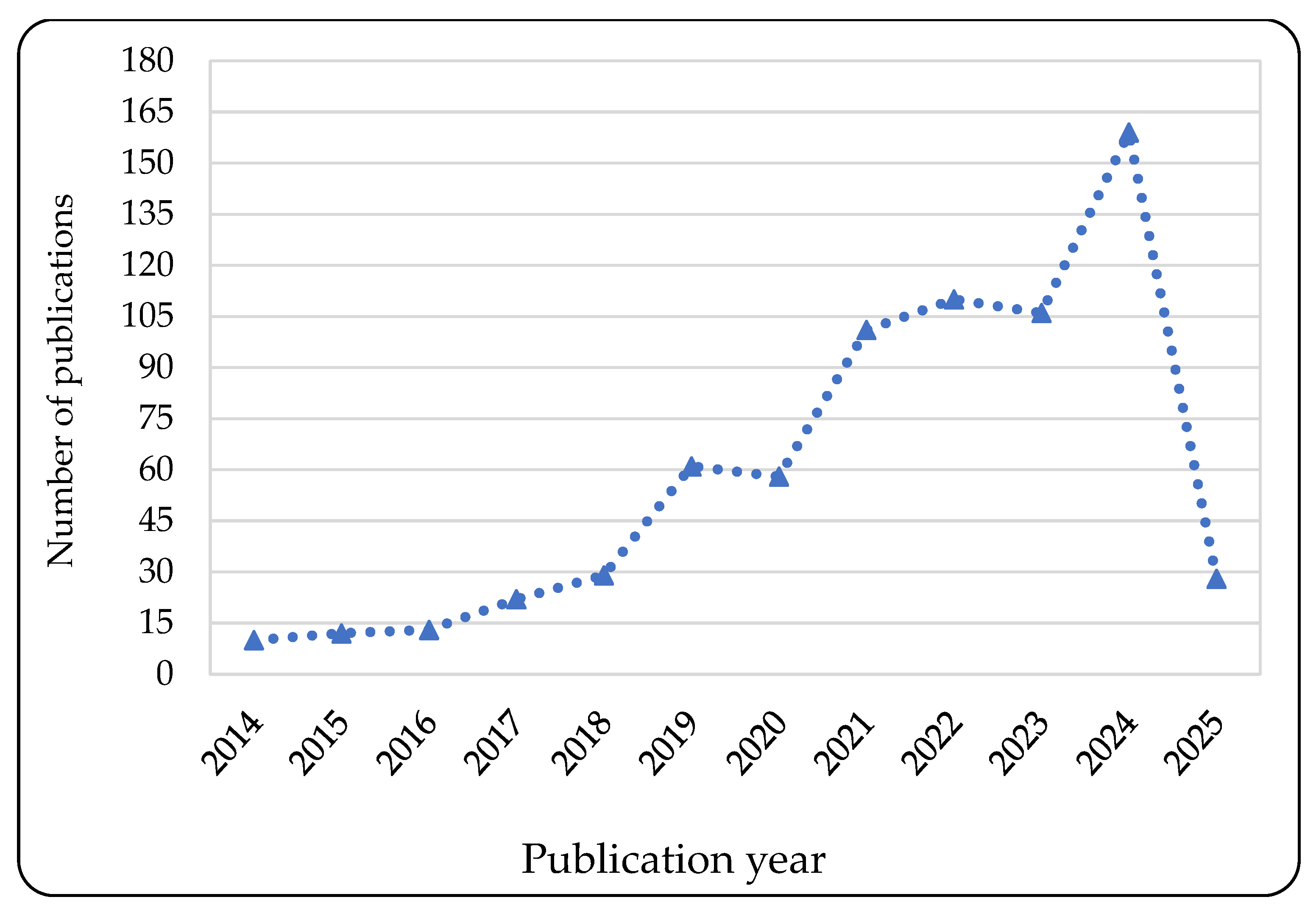

4.1. Characteristics of Data

4.2. Publication Trends on Climate Change, Smallholder Farming, and Sustainable Interventions

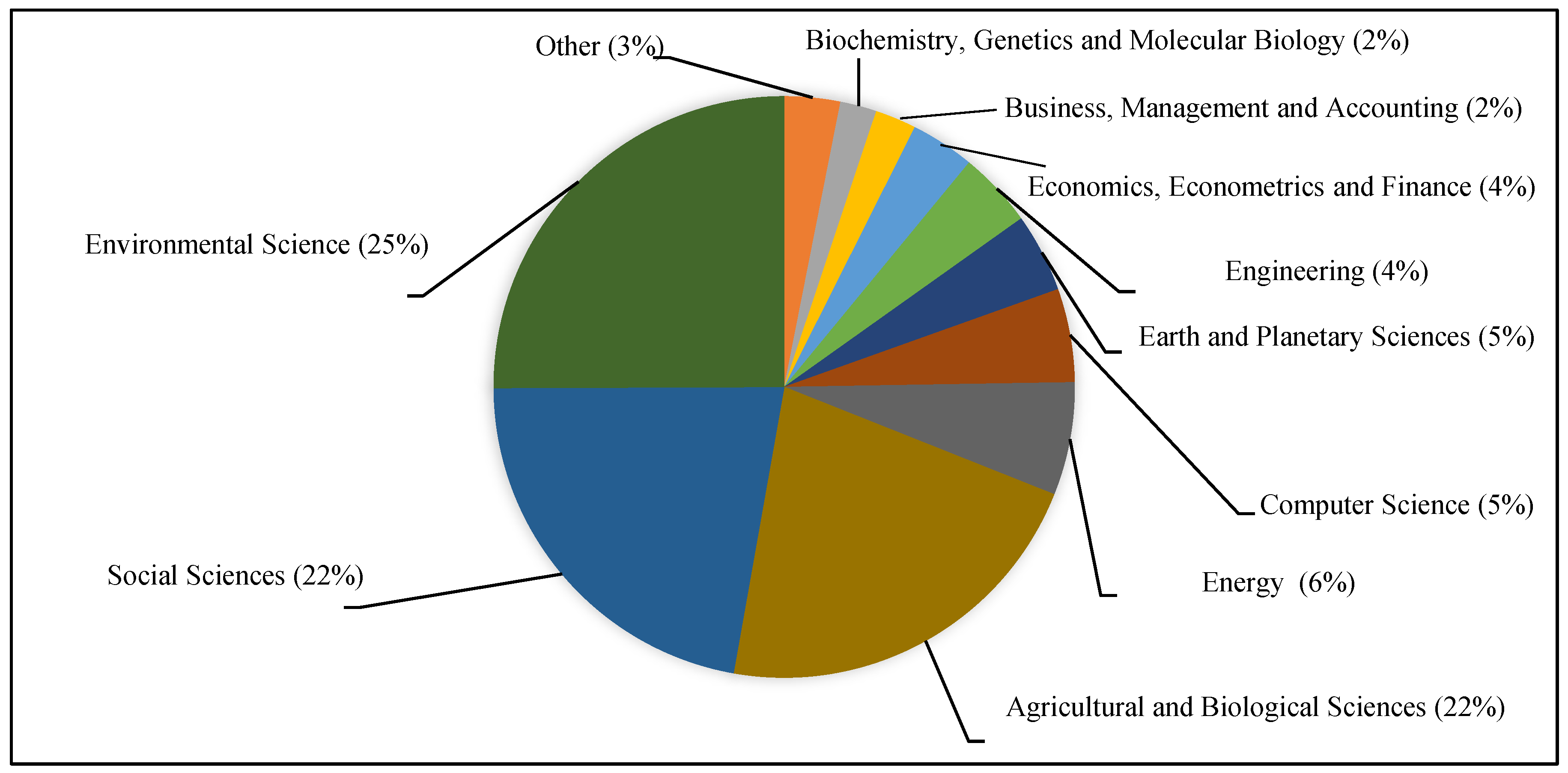

4.3. Distribution of Subject Areas on Climate Change, Smallholder Farmers’ Vulnerability and Sustainable Agricultural Interventions

4.4. Cited Publications on Climate Change, Smallholder Farmers’ Vulnerability, and Sustainable Agricultural Interventions

| Reference | Source Title | Citations | DOI | Document Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senyolo et al. [47] | Journal of Cleaner Production | 152 | 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.019 | Article |

| Abegunde et al. [48] | Sustainability | 138 | 10.3390/SU12010195 | Article |

| Tongwane and Moeletsi [50] | Environmental Development | 110 | 10.1016/j.envdev.2016.06.004 | Article |

| Myeni and Moeletsi [51] | Sustainability | 79 | 10.3390/su11113003 | Article |

| Sinyolo [52] | Technology in Society | 69 | 10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101214 | Article |

| Kom et al. [53] | GeoJournal | 62 | 10.1007/s10708-020-10272-7 | Article |

| Olorunfemi et al. [54] | Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences | 56 | 10.1016/j.jssas.2019.03.003 | Article |

| Ojo et al. [55] | Science of the Total Environment | 52 | 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148499 | Article |

| Mutengwa et al. [56] | Sustainability | 51 | 10.3390/su15042882 | Review |

| Swanepoel et al. [57] | South African Journal of Plant and Soil | 41 | 10.1080/02571862.2017.1390615 | Review |

| Popoola et al. [58] | Sustainability | 40 | 10.3390/su12145846 | Article |

| Zerihun et al. [59] | Development Studies Research | 39 | 10.1080/21665095.2014.977454 | Article |

| Cammarano et al. [60] | Food Security | 38 | 10.1007/s12571-020-01023-0 | Article |

| Ncoyini et al. [61] | Climate Services | 34 | 10.1016/j.cliser.2022.100285 | Article |

| Pangapanga-Phiri and Mungatana [62] | International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | 32 | 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102322 | Article |

| Khoza et al. [63] | Gender, Technology and Development | 31 | 10.1080/09718524.2020.1830338 | Article |

| Muzangwa et al. [64] | Agronomy | 31 | 10.3390/agronomy7030046 | Article |

| Popoola et al. [65] | GeoJournal | 30 | 10.1007/s10708-017-9829-0 | Article |

| Myeni and Moeletsi [66] | Agriculture | 29 | 10.3390/agriculture10090410 | Article |

| Ogundeji [49] | Agriculture | 27 | 10.3390/agriculture12050589 | Article |

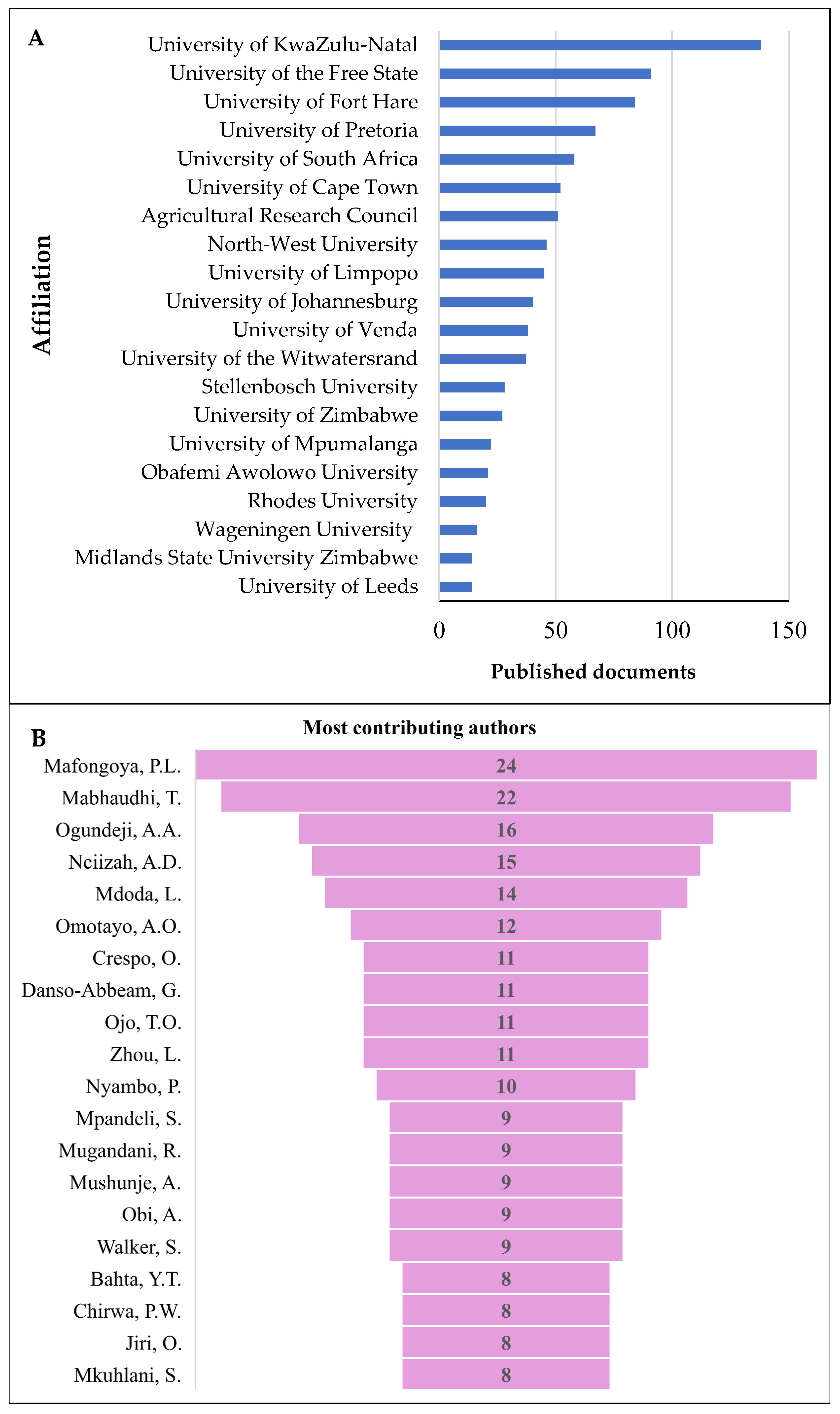

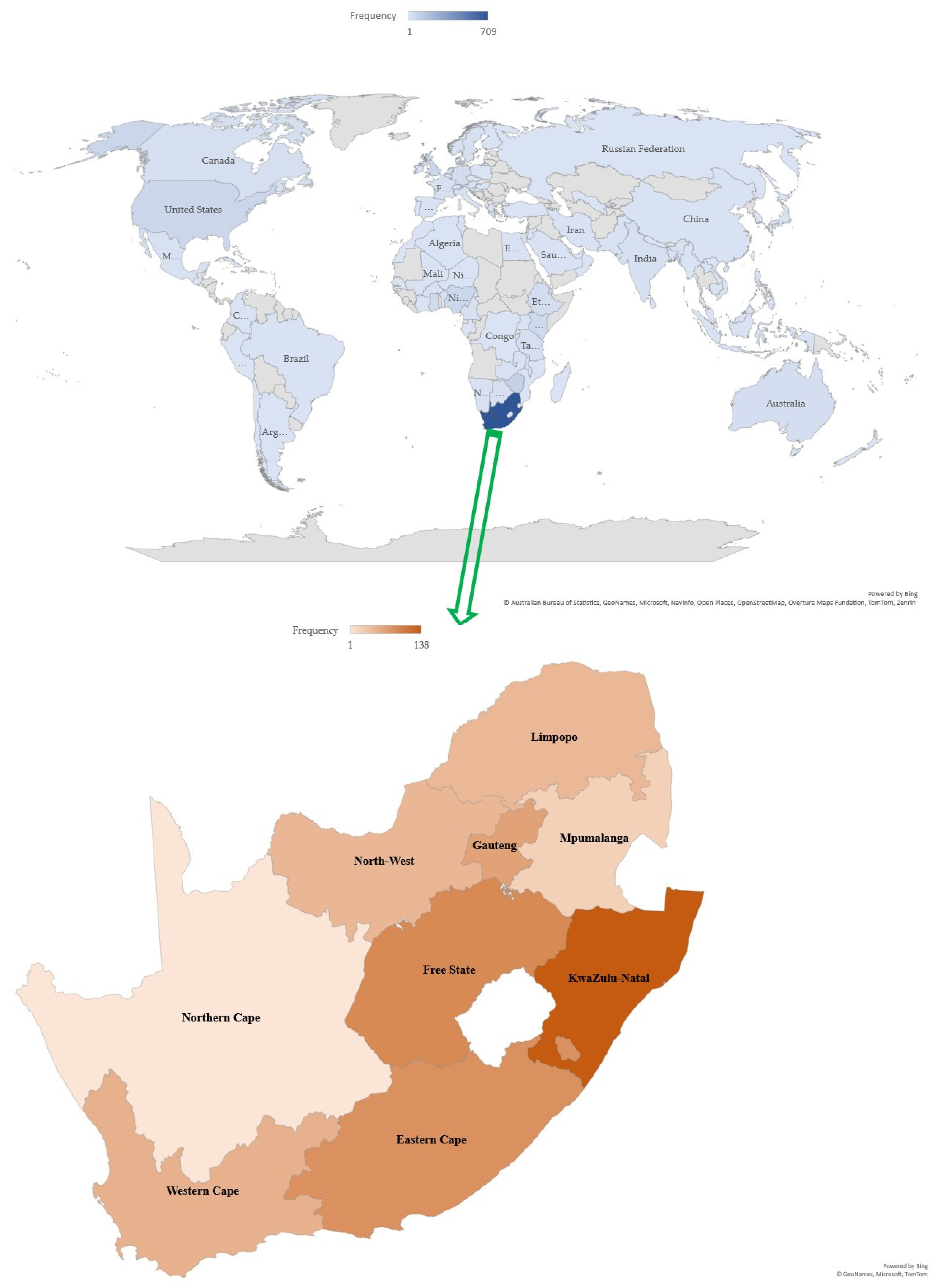

4.5. Affiliations, Contributing Authors and Geographic Distribution of Research on Climate Change, Smallholder Farming, and Sustainable Agricultural Interventions

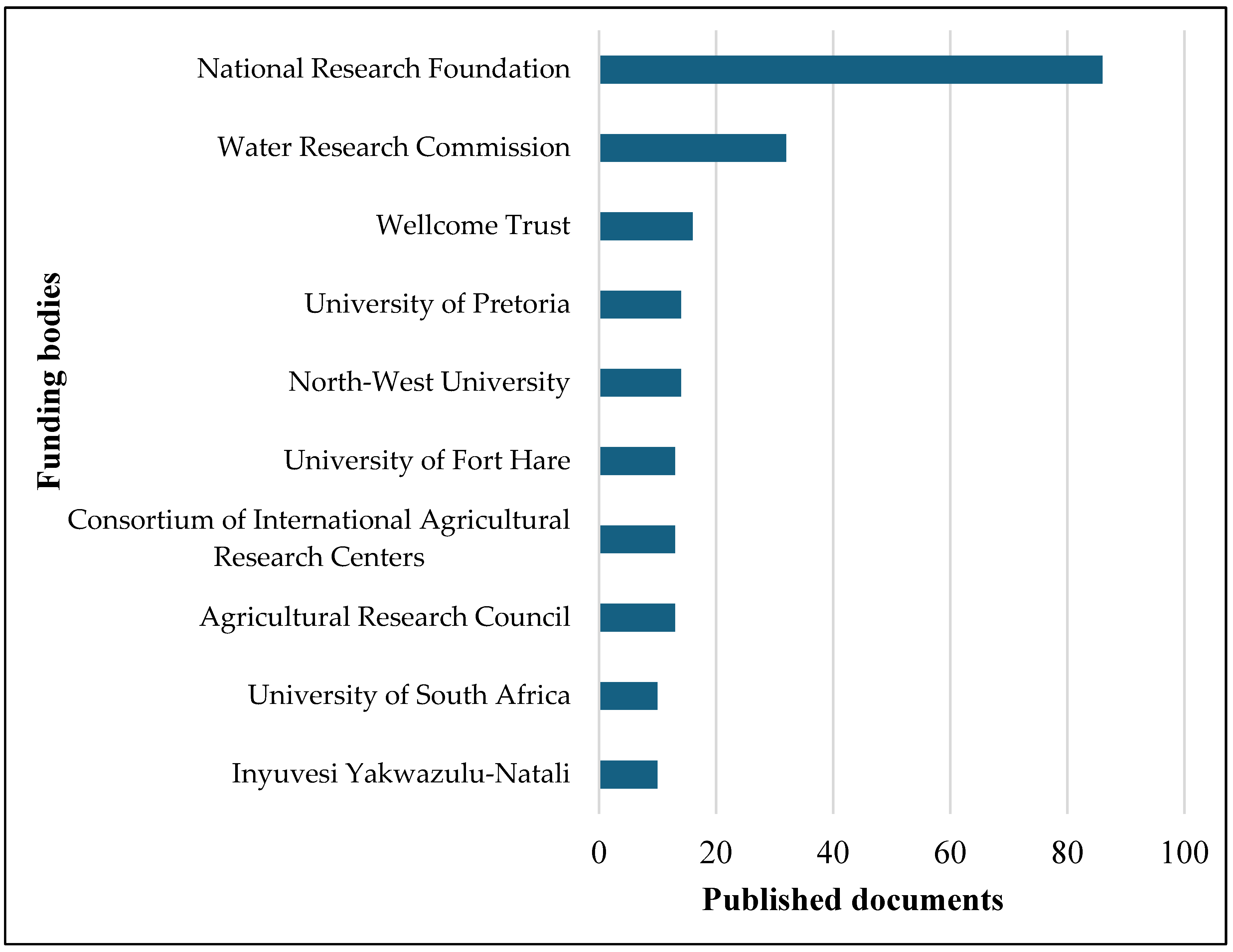

4.6. Funding Organisations

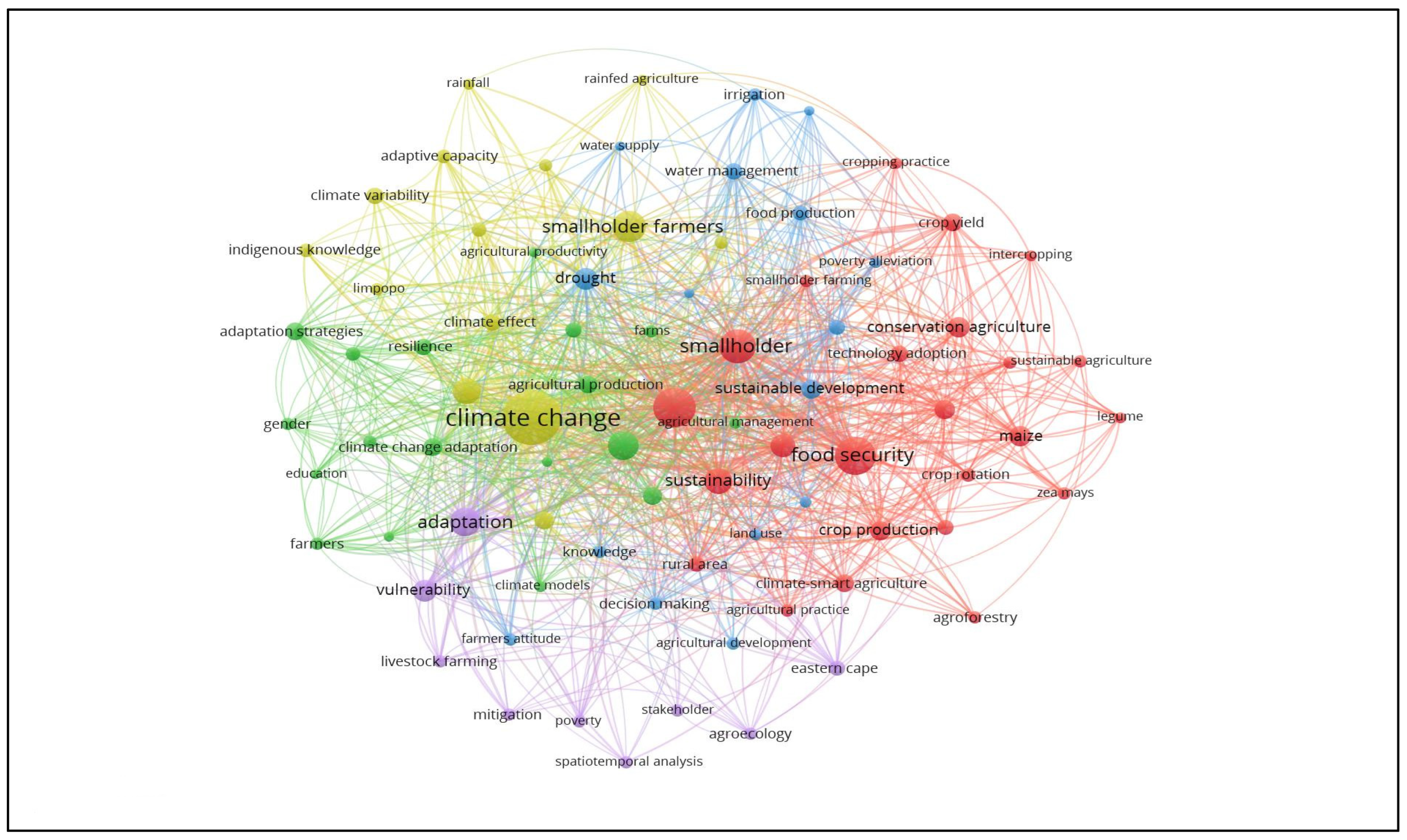

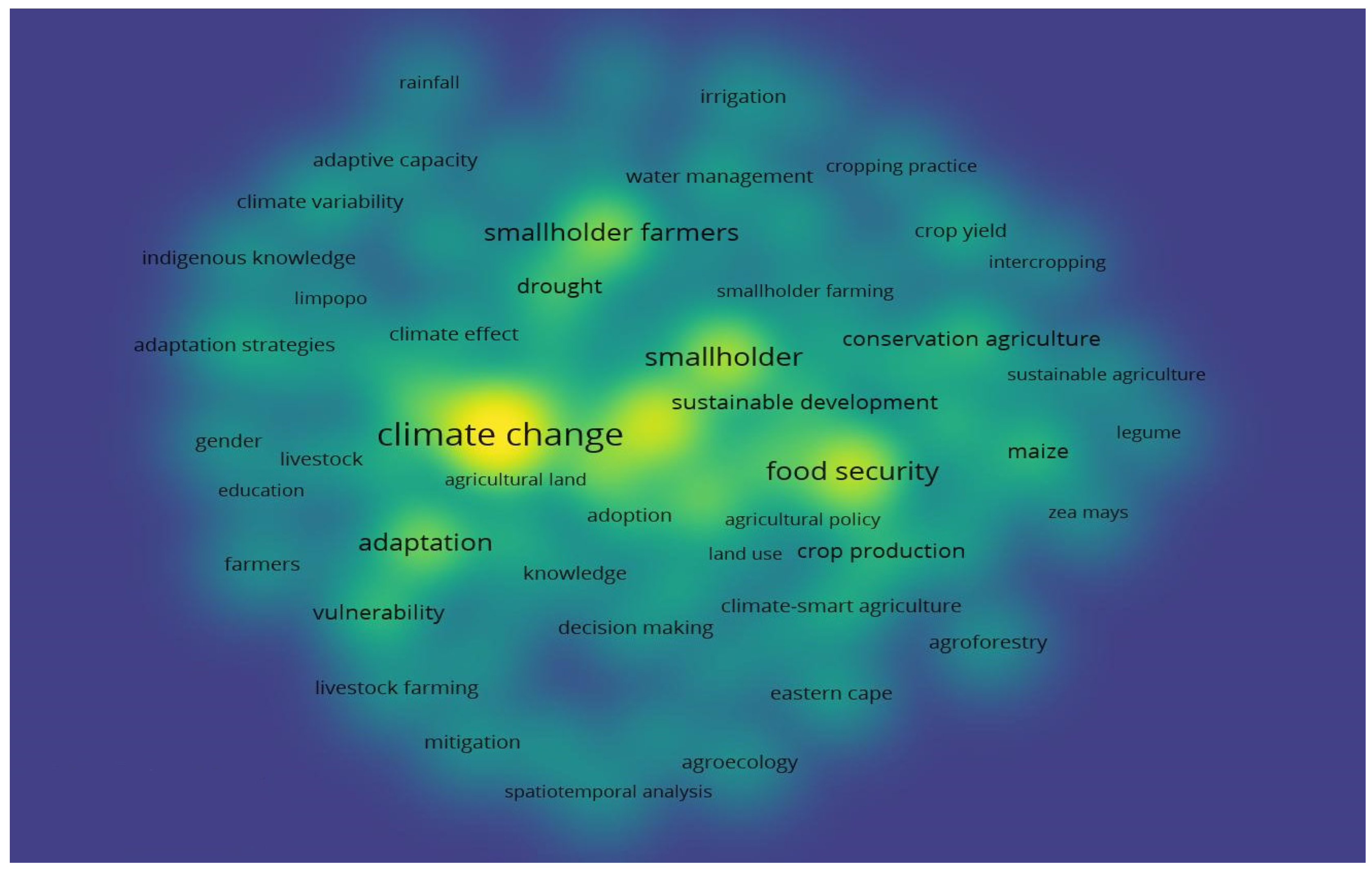

4.7. Keyword Co-Occurrence in Climate Change, Smallholder Farmers’ Vulnerability, and Sustainable Agricultural Interventions

4.8. Key Findings on Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change

5. Limitations, Practical Implications, and Opportunities for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASSAf | Academy of Science of South Africa |

| CSA | Climate-smart agriculture |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SSA | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| NRF | National Research Foundation |

| WRC | Water Research Commission |

References

- Anik, A.R.; Rahman, S.; Sarker, J.R. Five Decades of Productivity and Efficiency Changes in World Agriculture (1969–2013). Agriculture 2020, 10, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofiu, T.T.; Akande, R.S.; Abdulkareem, H.K.K.; Jimoh, S.O. Does the Relative Size of Agricultural Exports Matter for Sustainable Development? Evidence from Sub-Sahara Africa. World Dev. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, G.; Cacchiarelli, L.; Haug, R.; Sorrentino, A. Promoting Sustainable Change of Smallholders’ Agriculture in Africa: Policy and Institutional Implications from a Socio-Economic Cross-Country Comparative Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 358, 131949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa. Africa 2030: SDGs Within Social Boundaries Leave No One Behind Outlook. 2021. Available online: https://sdgs.opm.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Uganda-VNR-Report-2020.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Bhatnagar, S.; Chaudhary, R.; Sharma, S.; Janjhua, Y.; Thakur, P.; Sharma, P.; Keprate, A. Exploring the Dynamics of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices for Sustainable Resilience in a Changing Climate. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Majaha, J.; Chikwanha, O.C.; Dzama, K.; Kgasago, N.; Mapiye, C. Drought’s Implications on Agricultural Skills in South Africa. Outlook Agric. 2022, 51, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Elshorbagy, A.; Helgason, W. Assessment of Agricultural Adaptations to Climate Change from a Water-Energy-Food Nexus Perspective. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 284, 108343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Nadeem, F.; Nawaz, A.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Heat Stress Effects on the Reproductive Physiology and Yield of Wheat. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2022, 208, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Muchenje, V. Hair Coat Characteristics and Thermophysiological Stress Response of Nguni and Boran Cows Raised under Hot Environmental Conditions. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 2183–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikwanha, O.C.; Mupfiga, S.; Olagbegi, B.R.; Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Molotsi, A.H.; Abiodun, B.J.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Impact of Water Scarcity on Dryland Sheep Meat Production and Quality: Key Recovery and Resilience Strategies. J. Arid Environ. 2021, 190, 104511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K.A., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 3–22. ISBN 9781139177245. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi-Agyei, P.; Baffour-Ata, F.; Alhassan, J.; Kpenekuu, F.; Dougill, A.J. Understanding the Barriers and Knowledge Gaps to Climate-Smart Agriculture and Climate Information Services: A Multi-Stakeholder Analysis of Smallholder Farmers’ Uptake in Ghana. World Dev. Sustain. 2025, 6, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mthethwa, K.N.; Ngidi, M.S.C.; Ojo, T.O.; Hlatshwayo, S.I. The Determinants of Adoption and Intensity of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices among Smallholder Maize Farmers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slayi, M.; Zhou, L.; Jaja, I.F. Constraints Inhibiting Farmers’ Adoption of Cattle Feedlots as a Climate-Smart Practice in Rural Communities of the Eastern Cape, South Africa: An in-Depth Examination. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selokane, B.; Maseko, N.; Cira, N.; Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Mazenda, A. Towards Resilient Farming: Addressing Climate-Smart Agriculture Constraints in Selected Southern African Countries. SN Soc. Sci. 2025, 5, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, N.Z.; Mdoda, L.; Sibanda, M. Uptake and Level of Use of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices by Small-Scale Urban Crop Farmers in EThekwini Municipality. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, A.B.; Omotayo, A.O. The Interplay between Agriculture, Greenhouse Gases, and Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. Reg. Environ. Change 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenda, M. A Systematic Literature Review on the Impact of Climate Change on the Livelihoods of Smallholder Farmers in South Africa. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Slayi, M.; Ngarava, S.; Jaja, I.F.; Musemwa, L. A Systematic Review of Climate Change Risks to Communal Livestock Production and Response Strategies in South Africa. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 868468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenda, M.; Rodolph, M.; Harley, C. The Impact of Climate Variability on the Livelihoods of Smallholder Farmers in an Agricultural Village in the Wider Belfast Area, Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.M.; Klein, R.J.T. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessments: An Evolution of Conceptual Thinking. Clim. Change 2006, 75, 301–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, O.; Asadi, A.; Kalantari, K.; Azadi, H.; Scheffran, J. Vulnerability to Climate Change of Smallholder Farmers in the Hamadan Province, Iran. Clim. Risk Manag. 2019, 23, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Ghosh, A.; Hazra, S.; Ghosh, T.; Safra de Campos, R.; Samanta, S. Linking IPCC AR4 & AR5 Frameworks for Assessing Vulnerability and Risk to Climate Change in the Indian Bengal Delta. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 7, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Burton, I.; Challenger, B.; Huq, S.; Klein, R.; Yohe, G.; Adger, W.; Downing, T.; Harvey, E.; Kane, S.; et al. Adaptation to Climate Change in the Context of Sustainable Development and Equity. In Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 879–912. [Google Scholar]

- Henri Aurélien, A.B. Vulnerability to Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa Countries. Does International Trade Matter? Heliyon 2025, 11, e42517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Ahmed, M.Y.; Owusu, P.A. Global Adaptation Readiness and Income Mitigate Sectoral Climate Change Vulnerabilities. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Khan, M.M.; Lodhi, R.H.; Altaf, S.; Nawaz, A.; Najam, F.A. Multidimensional Poverty Vis-à-Vis Climate Change Vulnerability: Empirical Evidence from Flood-Prone Rural Communities of Charsadda and Nowshera Districts in Pakistan. World Dev. Sustain. 2023, 2, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcamu, B. Climate Change and Disaster Preparedness Issues in Eastern Cape and Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Town Reg. Plan. 2022, 81, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, T.A.; Delaney, A.; Tamás, P.A.; Chesterman, S.; Ericksen, P. A Systematic Review of Local Vulnerability to Climate Change in Developing Country Agriculture. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosperi, P.; Allen, T.; Cogill, B.; Padilla, M.; Peri, I. Towards Metrics of Sustainable Food Systems: A Review of the Resilience and Vulnerability Literature. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2016, 36, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumel, D.Y. Assessing Climate Change Vulnerability: A Conceptual and Theoretical Review. Rev. Artic. J. Sustain. Environ. Manag. 2022, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Goswami, K. Progress in Agricultural Vulnerability and Risk Research in India: A Systematic Review. Reg. Environ. Change 2021, 21, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, C.C.; Danso-Abbeam, G.; Groupson-Paul, O.; Ogundeji, A.A. Climate-Smart Agriculture amidst Climate Change to Enhance Agricultural Production: A Bibliometric Analysis. Land 2023, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, R.A.; McManus, C. Bibliographic Mapping of Animal Genetic Resources and Climate Change in Farm Animals. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McManus, C.; Pimentel, F.; de Almeida, A.M.; Pimentel, D. Tropical Animal Health and Production: A 55-Year Bibliographic Analysis Setting the Course for a Globalized International Reference Journal. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasa, P.M.; Botai, C.M.; Botai, J.O.; Mabhaudhi, T. A Review of Climate-Smart Agriculture Research and Applications in Africa. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimi, P.M.; Fobane, J.L.; Matick, J.H.; Mala, W.A. A Two-Decade Bibliometric Review of Climate Resilience in Agriculture Using the Dimensions Platform. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to Design Bibliometric Research: An Overview and a Framework Proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidi, A.; Ajibade, S.S.M.; Shah, M.A.; Bashir, F.M.; Falude, E.; Dodo, Y.A.; Adewolu, A.O.; Ngo-Hoang, D.L. Evolution of Climate-Smart Agriculture Research: A Science Mapping Exploration and Network Analysis. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoko, K.D.; Musakwa, W.; Kelso, C. A Bibliometric Analysis of Smallholder Farmers’ Climate Change Adaptation Challenges: A SADC Region Outlook. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2024, 17, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, W.; He, Q. Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices for Enhanced Farm Productivity, Income, Resilience, and Greenhouse Gas Mitigation: A Comprehensive Review. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2024, 29, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantlana, B.; Nondlazi, B.X.; Naidoo, S.; Ramoelo, A. Insights on Who Funds Climate Change Adaptation Research in South Africa. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyolo, M.P.; Long, T.B.; Blok, V.; Omta, O. How the Characteristics of Innovations Impact Their Adoption: An Exploration of Climate-Smart Agricultural Innovations in South Africa. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3825–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, V.O.O.; Sibanda, M.; Obi, A. Determinants of the Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices by Small-Scale Farming Households in King Cetshwayo District Municipality, South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundeji, A.A. Adaptation to Climate Change and Impact on Smallholder Farmers’ Food Security in South Africa. Agriculture 2022, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongwane, M.; Mdlambuzi, T.; Moeletsi, M.; Tsubo, M.; Mliswa, V.; Grootboom, L. Greenhouse gas emissions from different crop production and management practices in South Africa. Environ. Dev. 2016, 19, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Thavhana, M.; Randela, M.; Mokoena, L. Barriers Affecting Sustainable Agricultural Productivity of Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Free State of South Africa. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinyolo, S. Technology Adoption and Household Food Security among Rural Households in South Africa: The Role of Improved Maize Varieties. Technol. Soc. 2020, 60, 100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kom, Z.; Nethengwe, N.S.; Mpandeli, N.S.; Chikoore, H. Determinants of Small-Scale Farmers’ Choice and Adaptive Strategies in Response to Climatic Shocks in Vhembe District, South Africa. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olorunfemi, T.O.; Olorunfemi, O.D.; Oladele, O.I. Determinants of the Involvement of Extension Agents in Disseminating Climate Smart Agricultural Initiatives: Implication for Scaling Up. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2020, 19, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, T.O.; Adetoro, A.A.; Ogundeji, A.A.; Belle, J.A. Quantifying the Determinants of Climate Change Adaptation Strategies and Farmers’ Access to Credit in South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutengwa, C.S.; Mnkeni, P.; Kondwakwenda, A. Climate-Smart Agriculture and Food Security in Southern Africa: A Review of the Vulnerability of Smallholder Agriculture and Food Security to Climate Change. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, C.M.; Swanepoel, L.H.; Smith, H.J. A Review of Conservation Agriculture Research in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Plant Soil 2018, 35, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.O.; Yusuf, S.F.G.; Monde, N. Information Sources and Constraints to Climate Change Adaptation amongst Smallholder Farmers in Amathole District Municipality, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerihun, M.F.; Muchie, M.; Worku, Z. Determinants of Agroforestry Technology Adoption in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Dev. Stud. Res. 2014, 1, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cammarano, D.; Valdivia, R.O.; Beletse, Y.G.; Durand, W.; Crespo, O.; Tesfuhuney, W.A.; Jones, M.R.; Walker, S.; Mpuisang, T.N.; Nhemachena, C.; et al. Integrated Assessment of Climate Change Impacts on Crop Productivity and Income of Commercial Maize Farms in Northeast South Africa. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncoyini, Z.; Savage, M.J.; Strydom, S. Limited Access and Use of Climate Information by Small-Scale Sugarcane Farmers in South Africa: A Case Study. Clim. Serv. 2022, 26, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangapanga-Phiri, I.; Mungatana, E.D. Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices and Their Influence on the Technical Efficiency of Maize Production under Extreme Weather Events. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoza, S.; de Beer, L.T.; van Niekerk, D.; Nemakonde, L. A Gender-Differentiated Analysis of Climate-Smart Agriculture Adoption by Smallholder Farmers: Application of the Extended Technology Acceptance Model. Gend. Technol. Dev. 2021, 25, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzangwa, L.; Mnkeni, P.N.S.; Chiduza, C. Assessment of Conservation Agriculture Practices by Smallholder Farmers in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Agronomy 2017, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.O.; Monde, N.; Yusuf, S.F.G. Perceptions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Measures Used by Crop Smallholder Farmers in Amathole District Municipality, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. GeoJournal 2018, 83, 1205–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, L.; Moeletsi, M.E. Factors Determining the Adoption of Strategies Used by Smallholder Farmers to Cope with Climate Variability in the Eastern Free State, South Africa. Agriculture 2020, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damons, A. Research Chairs Focus on the Impact of Climate Change; University of the Free State: Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Filho, W.L.; Sierra, J.; Kalembo, F.; Ayal, D.Y.; Matandirotya, N.; de Victoria Pereira Amaro da Costa, C.I.; Sow, B.L.; Aabeyir, R.; Mawanda, J.; Zhou, L.; et al. The Role of African Universities in Handling Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). Second Biennial Report to Cabinet on the State of Climate Change Science and Technology in South Africa; Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf): Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf). First Biennial Report to Cabinet on the State of Climate Change Science and Technology in South Africa; Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf): Pretoria, South Africa, 2017; ISBN 9780994711700. [Google Scholar]

- Chitakira, M.; Ngcobo, N.Z.P. Uptake of Climate Smart Agriculture in Peri-Urban Areas of South Africa’s Economic Hub Requires up-Scaling. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 706738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Kori, D.S.; Sibanda, M.; Nhundu, K. An Analysis of the Differences in Vulnerability to Climate Change: A Review of Rural and Urban Areas in South Africa. Climate 2022, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlahla, S.; Ngidi, M.; Duma, S.E.; Sobratee-Fajurally, N.; Modi, A.T.; Slotow, R.; Mabhaudhi, T. Policy Gaps and Food Systems Optimization: A Review of Agriculture, Environment, and Health Policies in South Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 867481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Research Foundation NRF. VISION 2030: Reimagining the Future. 2025. Available online: https://www.saasta.ac.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/NRF-Vision-2030.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Water Research Commission. Annual Report 2023/2024; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Murugani, V.G.; Pereira, L.M.; Sobratee, N.; Govender, L.; Slotow, R.; Modi, A.T. Mainstreaming Underutilized Indigenous and Traditional Crops into Food Systems: A South African Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Mpandeli, S.; Nhamo, L.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Nhemachena, C.; Senzanje, A.; Naidoo, D.; Modi, A.T. Prospects for Improving Irrigated Agriculture in Southern Africa: Linking Water, Energy and Food. Water 2018, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpandeli, S.; Nhamo, L.; Moeletsi, M.; Masupha, T.; Magidi, J.; Tshikolomo, K.; Liphadzi, S.; Naidoo, D.; Mabhaudhi, T. Assessing Climate Change and Adaptive Capacity at Local Scale Using Observed and Remotely Sensed Data. Weather Clim. Extrem. 2019, 26, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokool, S.; Mahomed, M.; Kunz, R.; Clulow, A.; Sibanda, M.; Naiken, V.; Chetty, K.; Mabhaudhi, T. Crop Monitoring in Smallholder Farms Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles to Facilitate Precision Agriculture Practices: A Scoping Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abafe, E.A.; Bahta, Y.T.; Jordaan, H. Exploring Biblioshiny for Historical Assessment of Global Research on Sustainable Use of Water in Agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, G.P.; Bavorova, M.; Ullah, A.; Pradhan, P. Food Security and Sustainability through Adaptation to Climate Change: Lessons Learned from Nepal. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 101, 104279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molua, E.L.; Sonwa, D.; Bele, Y.; Foahom, B.; Mate Mweru, J.P.; Wa Bassa, S.M.; Gapia, M.; Ngana, F.; Joe, A.E.; Masumbuko, E.M. Climate-Smart Conservation Agriculture, Farm Values and Tenure Security: Implications for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation in the Congo Basin. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 16, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, V.O.; Obi, A. The Role and Perspective of Climate Smart Agriculture in Africa: A Scientific Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabato, W.; Getnet, G.T.; Sinore, T.; Nemeth, A.; Molnár, Z. Towards Climate-Smart Agriculture: Strategies for Sustainable Agricultural Production, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Reduction. Agronomy 2025, 15, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanlade, A.; Oluwaranti, A.; Ayanlade, O.S.; Borderon, M.; Sterly, H.; Sakdapolrak, P.; Jegede, M.O.; Weldemariam, L.F.; Ayinde, A.F.O. Extreme Climate Events in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Call for Improving Agricultural Technology Transfer to Enhance Adaptive Capacity. Clim. Serv. 2022, 27, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füssel, H.M. Vulnerability: A Generally Applicable Conceptual Framework for Climate Change Research. Glob. Environ. Change 2007, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupfiga, S.; Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Chikwanha, O.C.; Molotsi, A.H.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Meat Production, Feed and Water Efficiencies of Selected South African Sheep Breeds. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 214, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagbegi, B.R.; Chikwanha, O.C.; Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Marais, J.; Molotsi, A.H.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Physicochemical, Volatile Compounds, Oxidative and Sensory Profiles of the Longissimus Muscle of Six South African Sheep Breeds. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2023, 63, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimani, T.; Marandure, T.; Chikwanha, O.C.; Molotsi, A.H.; Abiodun, B.J.; Dzama, K.; Mapiye, C. Smallholder Sheep Farmers’ Perceived Impact of Water Scarcity in the Dry Ecozones of South Africa: Determinants and Response Strategies. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 34, 100369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K. Family Farming in Climate Change: Strategies for Resilient and Sustainable Food Systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogisi, O.D.; Begho, T. Adoption of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Progress, Barriers, Gender Differences and Recommendations. Farming Syst. 2023, 1, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoko, K.D.; Kelso, C.; Musakwa, W. Climate Change Adaptation by Smallholder Farmers in Southern Africa: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Review. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Results |

|---|---|

| Period | 2014:2025 |

| Sources | 574 |

| Documents | 709 |

| Annual growth rate (%) | 28.6 |

| Document average age | 3.51 |

| Average citation per document | 13.84 |

| Keywords plus (ID) | 3494 |

| Author’s keywords (DE) | 2940 |

| Authors | 833 |

| Authors of single authored documents | 42 |

| Single authored documents | 45 |

| Co-authors per document | 1.19 |

| International co-authorship (%) | 47.95 |

| Article | 503 |

| Review | 115 |

| Book chapter | 80 |

| Conference paper | 5 |

| Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | 231 | 1136 |

| Smallholder | 96 | 667 |

| South Africa | 121 | 615 |

| Food security | 112 | 460 |

| Adaptive management | 52 | 411 |

| Agriculture | 64 | 395 |

| Adaptation | 68 | 363 |

| Smallholder farmers | 76 | 317 |

| Farming system | 42 | 304 |

| Sustainability | 54 | 207 |

| Cluster | Extracted Theme | Selected Keywords | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Red cluster | Climate-smart agronomic practices and food security | Agroforestry, conservation agriculture, crop rotation, intercropping, maize, legume, CSA, agricultural technology, cropping practice, farming system, sustainable agriculture, sustainability | Technology-driven adaptation to improve production and food security. |

| Green cluster | Climate change adaptation and resilience | Climate change adaptation, adoption, climate models, agricultural management, adaptation strategies, education, gender, farmers’ knowledge | Sociocultural and agro-ecological strategies, knowledge and skills are important in climate change mitigation and building resilience. |

| Blue cluster | Water management and agricultural development | Agricultural policy, decision making, water management, water supply, water use efficiency, poverty alleviation, food production, food supply, irrigation, land use | The government plays an essential role in building resilience of farmers. |

| Yellow cluster | Climate change indicators, agricultural productivity and smallholder farmers | Rainfall, climate variability, climate effect, rainfed agriculture, indigenous knowledge, smallholder farmers | Climate variability is a direct threat to smallholder farmers as it influences agricultural productivity. |

| Purple cluster | Socioeconomic and spatial aspects | Vulnerability, agroecology, mitigation, livestock farming, adaptation, poverty, spatiotemporal analysis, stakeholder | Diverse coping mechanisms to climate change involving risk assessment, adaptation capacity and farming systems. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Katiyatiya, C.L.F.; Ncanywa, T. Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change in South African Smallholder Systems: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2026, 18, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010114

Katiyatiya CLF, Ncanywa T. Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change in South African Smallholder Systems: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatiyatiya, Chenaimoyo Lufutuko Faith, and Thobeka Ncanywa. 2026. "Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change in South African Smallholder Systems: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010114

APA StyleKatiyatiya, C. L. F., & Ncanywa, T. (2026). Sustainable Agricultural Interventions to Climate Change in South African Smallholder Systems: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 18(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010114