Abstract

This study explores the concept of hybridity in architecture, shaped by cultural exchange, globalization, and evolving socio-political contexts. In this research, hybridity in architecture is defined as a dynamic process that emerges within boundary spaces, where physical elements interact with evolving cultural, social, and political forces, resulting in adaptable and multilayered architectural environments. Despite the significance of hybridity in architecture, existing research lacks a comprehensive and systematic framework for its analysis. To bridge this gap, the study develops a conceptual framework that integrates archival research, literature synthesis, and an architectural analysis. The methodology combines a qualitative analysis of historical documents and design drawings to identify eight key indicators of hybridity—form, typology, program, mixed-use, multi-layering, user mixing, border spaces, and control/resistance—and applies them to a case study of the University of Baghdad. These indicators embody the interaction between the static and kinetic aspects of hybridity. The Static Aspect refers to the tangible outcomes of hybridity—such as mixed forms and functions—that materialize in built structures. In contrast, the Kinetic Aspect reflects the intangible dimensions, including ongoing social and cultural dynamics and shifts in power relations, which continuously reshape these hybrid forms. Together, these aspects illustrate that hybridity is both a product and a process, where material expressions emerge from social negotiations and, in turn, influence future adaptations. The findings reveal that the hybrid architecture evolves through complex interactions among historical references, contemporary needs, and socio-political forces. By establishing a systematic methodology for analyzing hybridity, this study bridges theoretical discourse with practical applications, providing architects and researchers with a robust analytical tool to assess hybrid architectural spaces within culturally diverse contexts. It also reinforces the understanding of hybridity as a dynamic force—one that not only results in physical architectural expressions but also evolves through ongoing cultural, social, and political interactions.

1. Introduction

Architecture is an art form that reflects cultural, historical, and societal influences, shaping the built environment in unique and distinctive ways [1]. In recent years, there has been a growing academic and professional interest in the concept of hybridity in architecture, which involves the integration of various architectural styles, influences, and cultural elements within a single context to produce adaptable and context-responsive built environments [2]. This concept has gained considerable importance as architects increasingly seek to create designs that transcend traditional boundaries and embrace the richness of cultural pluralism and global exchange [3].

Although this concept has gained momentum only recently, its theoretical roots span broader fields of knowledge. Practices of hybridity have long existed across multiple civilizations before being formally defined, having developed through philosophy, art, and culture. Ancient societies often blended their own experiences with foreign influences in ideas, technologies, and arts [4]. Many scholars affirm that architectural hybridity has been practiced for centuries, through functional spatial responses such as houses above shops, apartments over bridges, and other structures that reflect hybrid configurations [5]. Despite lacking an explicit theoretical designation at the time, these early hybrid expressions laid the groundwork for contemporary understandings of hybridity, which formally emerged in the postmodern era [6].

Studies such as those by Morton [7] and Hernández [6] demonstrate that modern architecture in the non-Western world was not a neutral outcome but rather a reflection of colonial structures of domination and social ordering. Colonial powers systematically imposed classical European architectural forms to symbolize authority and discipline while marginalizing local styles as “backward”. The remnants of this architectural hegemony remain visible today, reinforcing the understanding of colonialism as an ongoing structure rather than a closed historical chapter [8].

Conversely, the modernization efforts in postcolonial periods led to a wave of architectural projects that attempted to break free from colonial symbolism, albeit without a complete rupture from the tools of Western modernity. Many of these projects, such as those in 1950s Iraq, sought to craft a national identity through modernist architectural expressions that embodied aspirations of independence and progress.

In the age of globalization, stylistic boundaries have become increasingly blurred. However, this blending is not unidirectional. As Alsayyad [2] notes, globalization is continuously recontextualized within specific social and cultural frameworks, producing hybrid conditions that facilitate the coexistence of seemingly opposing dualities—such as the local and global, traditional, and modern [3,9,10].

Over the past four decades, hybridity has become a widely discussed subject across multiple disciplines, including architecture and cultural studies, serving as a conceptual tool for understanding cultural adaptation, diversity, and innovation [3]. Within this discourse, postcolonial theory has emerged as a critical lens for interpreting architectural hybridity, especially in contexts where identities are being renegotiated in the aftermath of political liberation.

Homi Bhabha, one of the foremost postcolonial theorists, argues that hybridity is not merely the fusion of incompatible components but rather the product of a “Third Space”—a dynamic zone of cultural friction and interaction that generates new meanings. Similarly, Spivak, and Hall emphasize the need to analyze these spaces through the lenses of representation, power, and identity. A vivid architectural manifestation of this dynamic can be seen in Jean Nouvel’s Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, where the failure of singular cultural representations is revealed through hybrid structures that challenge conventional classifications [11].

Accordingly, hybridity goes beyond the simplistic idea of mixing disparate parts. As Bhabha argues [2], it emerges through encounters in which elements engage and transform each other. These hybrid spaces hold multiple layers of meaning and narrative, offering forms of cultural sustainability by integrating historical storytelling with contemporary needs. As such, they become landmarks embedded in community memory, shaping collective identities while enabling both continuity and rupture [2,3,4].

Within this framework, Richard Ingersoll stresses the importance of hybridity as an anthropological equivalent to biodiversity—a necessity for the survival of cities and architecture [12]. Just as hybridity fosters diversity and adaptability in ecological systems, it also provides architecture with the means to respond to its evolving socio-cultural context, generating hybrid forms and functions [13]. An awareness of hybridity thus becomes a celebration of complexity, diversity, and the overlaying of different activities and elements [14].

Building on this rich conceptual foundation, this study develops a comprehensive conceptual framework for analyzing hybridity in architecture. The framework explores hybridity across multiple dimensions—formal, functional, spatial, cultural, and ideological—offering a systematic methodology for understanding how architectural expressions evolve through the fusion of elements and cultural interactions.

The framework is applied to Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad, a project emblematic of intense historical and geopolitical transitions. This case study represents a unique confluence of British colonial withdrawal, the rise of a national identity, and an ambitious state-led modernization project. The university thus serves as an ideal site for analyzing architectural hybridity in its political, cultural, and formal dimensions.

Rather than evaluating the planning or functional efficiency of the university, the framework aims to demonstrate its analytical applicability for studying hybrid architectural spaces, paving the way for broader use across diverse contexts. Ultimately, this research contributes to the ongoing discourse on the complexities of creating and interpreting hybridity in architecture, supporting more culturally adaptive and sustainable design decisions. The next section offers the theoretical foundation of the study, followed by the development of the framework and its application to the selected case study.

2. Contextualization of the Research

2.1. Definition of Hybridity

The idea of hybridity has attracted theorists across various disciplinary fields and has aroused the interest of many researchers. Hybridity spans multiple fields and intersects with various concepts, making its definition complex and multifaceted. Evolving from its biological and botanical origins, it has become a key concept in racial, colonial, linguistic, and cultural studies. It has also gained significance in anthropology, geography, literature, sociology, and architecture. As a theoretical tool, hybridity helps analyze the interactions between physical and non-physical elements within diverse contexts, including colonialism and globalization, often symbolizing new combinations.

The term “hybrid” originated in biology and botany, referring to cross-pollination between species that produces a new hybrid form. Over time, genetics has redefined hybridity as a process leading to genetic modification [3]. Historically, hybrids were often perceived as impure mutations, a notion reinforced by eugenics and Social Darwinism, which influenced restrictive laws and discriminatory ideologies [15].

In the twentieth century, the concept of hybridity expanded beyond biological and racial frameworks to encompass linguistic and cultural domains. Mikhail Bakhtin introduced a linguistic interpretation of hybridity, describing it as a continuous and dynamic process that challenges the notion of a homogeneous and authoritative discourse [16].

Many postcolonial theorists have employed the term “hybridity” to describe the cultural transformations resulting from colonialism. Homi Bhabha emphasized the “Third Space” as a site of resistance and negotiation; meanwhile, Stuart Hall highlighted identity as a hybrid construct. In contrast, Gayatri Spivak problematized hybridity in relation to cultural representation and power [6,15]. These perspectives offer valuable insights into the spatial and symbolic dynamics that this study aims to explore within architectural contexts [6].

A synthesis of theoretical perspectives on hybridity reveals that it manifests across three key aspects:

- Hybrid by describing a result, a tangible result (object, decoration, architecture…) to mix and combine different elements, but at the same time, they have specific compositional qualities and characteristics. This perspective is reflected in Joseph Fenton’s work on hybrid buildings [5], and in the empirical studies conducted by the a+t research group on programmatic hybridity [14,16].

- Hybridity as a Process: this dimension reflects AlSayyad’s interpretation of hybridity as a continuous negotiation shaped by postcolonial and global forces [2]. It aligns with Bhabha’s concept of cultural production and transformation [6] and resonates with Bakhtin’s theory of dialogic interaction [16], which was later expanded by Stuart Hall [15].

- Hybridity as a Site: closely linked to Bhabha’s concept of the “Third Space” [6], this perspective sees hybridity as an unstable, marginal, or transitional site where multiple identities and meanings coexist—often in tension rather than in harmony. This idea is further echoed in spatial studies such as those by Murrani [17] and Ikas and Wagner [18], which explore hybrid border spaces as zones of cultural, social, and symbolic interaction.

Based on this synthesis, this study defines architectural hybridity as a multi-dimensional and dynamic process that emerges in boundary spaces, where physical elements interact with evolving cultural, social, and political forces—ultimately generating flexible and multilayered architectural environments.

2.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Hybridity: Postcolonial and Architecture

The answer to the question about the relationship between architecture and post-colonialism is simple and not complex. Early contributions included Brian Bryce Taylor’s 1984 editorial [11] on colonial architecture in Morocco, Tunisia, Mali, Egypt, and Indonesia and Chris Abel’s Architecture and Identity, which explored hybridity in colonial Malaysia [1]. Similarly, Nizar Al-Sayyad’s Hybrid Urbanism examined colonial domination and hybridity in French, Italian, and British colonies, highlighting its role in globalization [2].

Colonial ambitions to restructure cities led architecture and urban planning to become key tools in shaping colonial societies [11]. This created a complicity between architects and structures of social and cultural dominance, as architecture was used to impose a new social and political order and maintain colonial control [6]. George Simmel described the infrastructure projects carried out by British colonizers in Iraq as “visible institutions of the state”, embodying power through administrative structures [19]. These projects also formed tangible frameworks on the ground to implement taxation systems, land ownership regulations, law and order, as well as the broader roles of government [19].

Almost all master plans for colonial cities envisioned the segregation of populations, reserving different areas for colonial and colonized populations [11]. The colonized were seen as uneducated and backward and had to be taught the European way, which included how to live in an organized manner in the city (unlike the savages). The orthogonal grid system reinforced racial separation, keeping the colonized on the periphery or outside city walls, away from colonial elites.

From here, it is possible to understand how engineering, planning and “development” were an integral part of the act of the new state and was a large part of the colonizers’ vision of a nation in their own image [19]. Therefore, colonial cities can be considered the spatial embodiment of “civilization” that colonialism claimed to carry, while representing in itself the violence of colonialism [6]. In addition to spatial mechanisms of racial, ethnic, and sexual segregation, the most common concern of colonial architects was their confrontation with local building traditions and the urban fabric of the city. In this regard, practices that extend back to our time can be found, and this is based on the large-scale demolition of the existing urban fabric and the preservation of Western values of conservation [11]. In the re-planning of Basra in Iraq, for example, the replanning was not the seizure of land for trade, but it was also the annihilation and creation of a new city arranged on British lines, with the houses possessing all the characteristics of an “English house with additional construction to exclude the sun and heat produced” [19], and this process of appropriation even extends tangible physical aspects to intangible aspects, where a Map of Basra produced in 1918 is an attempt the British made themselves at home using familiar place names including Piccadilly Circus, Old Kent Road, and Oxford Street Jaipur, thus rejecting the local names, history, and memories [19]. Colonialism may seem like a distant past, especially in architecture, where terms like “colonial” and “postcolonial” are often linked to old buildings. However, many states fought for independence well into the late 20th century, making colonial experiences and the “end of the empire” era still relevant. These historical interactions continue to shape people’s perceptions and behaviors within similar environments [20].

The lasting influence of colonialism continues to shape architectural practices and discourse, reinforcing dominant Western perspectives. This study argues that postcolonial critical theory provides a valuable foundation for constructing a comprehensive conceptual framework for hybridity in architecture, systematically uncovering its complex layers. This aligns with previous studies that emphasize the role and significance of postcolonial theoretical concepts in enhancing our understanding of the relationship between architecture and the cultural and social contexts in which it emerged, contributing to a broader comprehension of this concept in architecture [2,6,7,8,21].

2.3. Hybridity in Architecture

Hybrid spaces in architecture serve as adaptive responses to cultural diversity and socio-political change, aligning with sustainability’s focus on preserving heritage while fostering social cohesion. Scholars such as Fernández Per and Mozas, Galina Ptichnikova, and Nezar AlSayyad emphasize that hybridity emerges as a means of problem-solving in urban life, reflecting the coexistence of multiple cultural groups within the built environment [2,9,22]. This dynamic interaction enables urban spaces to balance continuity and transformation, maintaining cultural identity while integrating new influences.

In colonial and postcolonial cities, hybridity arises through the reconfiguration of spaces, where imposed architectural forms merge with local adaptations. This process not only sustains cultural heritage but also contributes to its evolution, preventing complete erasure. As urban environments adapt to shifting socio-political contexts, hybrid architecture exemplifies resilience, offering a sustainable model for preserving identity while accommodating change [23].

While eclecticism in architecture often involves the direct borrowing of historical styles and motifs [24,25], hybridity represents a deeper process of cultural integration, adaptation, and transformation. Unlike eclecticism, which is often perceived as a superficial stylistic mix, hybridity emerges as a response to social, cultural, and political forces, making it a dynamic and evolving architectural process [2,6].

Hybridity in architecture extends beyond colonial cities to border zones, where cultural and functional negotiations shape spatial identity. Jan Pieterse highlights free enterprise zones, offshore banking hubs, and ethnic neighborhoods as spaces where hybridity emerges through interaction and exchange [2], border zones also extend to include the boundaries between public and private space, where hybridity will emerge as a result of negotiations, interface, and exchange across borders [26].

Despite their seemingly fixed nature, buildings embody evolving narratives of cultural adaptation. The fusion of local and global influences in forms, functions, and construction methods results in hybrid structures that respond to environmental, cultural, and contextual shifts [9]. This is evident in the transformation of the Bungalow style in India and the adaptation of housing styles on Penang Island, Malaysia, where decorative elements and spatial layouts were modified to reflect local influences [1,6,27].

Architecture today, as Katarzyna Pluta asserts, offers multiple models of hybridity that can be found everywhere around us, from industrial areas transformed into cultural areas, cemeteries used as public parks, and renewed historical spaces [28]. These transformations create an intermediate state where the adapted structure is neither entirely original nor entirely new. Rather than replicating the guest function, the building simultaneously embodies both its past and present identity, blurring the boundaries between them [2,29]. Rather than merely taking over a building and assimilating it into a new culture, adaptation creates an independent entity that bridges both cultures, maintaining continuity while embracing transformation. This interplay generates hybridity, where distinct elements coexist and interact without destroying each other [30].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Methods

This study adopts a multi-method qualitative approach to develop and validate a conceptual framework for analyzing hybridity in architecture. The methodology integrates archival research, case study analysis, architectural drawings and plans, and the analysis of visual and spatial culture, ensuring a robust and multidimensional exploration of the topic. The case study methodology—recognized as an effective strategy in postcolonial and architectural studies [2,5,6,7,8,9,17,21,22,28,31,32]—is central to this research. According to Tellis [33], case studies support triangulated research designs by enabling the use of diverse methods and sources of empirical evidence, including archival documentation, visual materials, and field observations.

3.2. Research Phases

The study follows a structured research design consisting of three main phases:

First: Theoretical and Literature Synthesis: A comprehensive literature review was conducted to consolidate theoretical perspectives on hybridity, drawing from postcolonial theory, cultural studies, and architectural discourse. Academic databases, such as Scopus, JSTOR, and ScienceDirect, were searched using keywords like “architectural hybridity”, “Thirdspace”, “postcolonial architecture”, and “hybrid buildings”. A sample of 31 core texts (9 books and 22 peer-reviewed articles) was selected and analyzed using thematic coding to extract recurring conceptual patterns of hybridity. These patterns were then synthesized into eight conceptual indicators.

Second: Framework Development: Based on the synthesis of the literature, eight core indicators of hybridity were identified: form, typology, program, mixed-use, multi-layering, user mixing, border spaces, and control/resistance. These indicators were refined through a systematic content analysis. Both explicit definitions and recurring themes related to hybridity were interpreted into applicable conceptual categories. The indicators were then organized into a matrix to guide an architectural analysis.

Third: Empirical Application and Validation: The proposed framework was applied to the design of the University of Baghdad as a case study. The analysis was grounded in multiple empirical sources, including the following:

- Archival architectural drawings and plans from the Gropius Foundation and The Architects Collaborative.

- Archival and contemporary photographs of the site and major buildings.

- Secondary sources such as previous academic studies, planning documents, and official records.

- Direct field observations of user interactions, accessibility, and movement within the campus.

These materials were analyzed through a manual coding process. Each researcher independently evaluated the indicators and recorded binary values (1 = presence of hybrid indicator; 0 = absence) in Table A1, based on predefined conceptual criteria. This was followed by group review sessions to compare outcomes and discuss discrepancies, helping to enhance internal consistency, interpretive reliability, and alignment with the theoretical framework.

This methodology bridges theory and practice and reinforces the analytical strength of the proposed framework, supporting the research objective of constructing a comprehensive conceptual tool for analyzing hybridity in architecture. The case study was treated as a “complete study”, in which multiple data types were integrated to generate meaningful conclusions, as recommended by Yin [34].

3.3. Case Study Selection: Baghdad University Campus

The University of Baghdad serves as the primary case study for applying and validating the proposed conceptual framework for hybridity in architecture. This selection is based on its unique historical, architectural, and cultural context, as well as its role in reflecting broader socio-political transformations.

The University of Baghdad holds significant importance as a symbolic structure of state-building in modern Iraq, particularly during the colonial and postcolonial periods. Its design reflects the influence of major political, cultural, and social changes, spanning three distinct iterations of development between 1954 and 1981. These transformations occurred across three political regimes and six rulers, paralleling Iraq’s shift from direct colonial rule to the postcolonial era. During this period, international firms, including The Architects Collaborative (TAC) led by Walter Gropius, played a pivotal role not only in designing the university but also in shaping its academic vision, particularly in the field of architectural education in Iraq [11,35,36].

The University of Baghdad campus is the largest project undertaken by Gropius and a significant example of modern architectural heritage in the Middle East. Given its broader spatial and geopolitical context, it offers valuable insights into how Western and American powers have used architecture to assert influence and reshape power dynamics in colonial and postcolonial societies. Therefore, it stands as a crucial site for analyzing hybridity in architecture across physical, functional, spatial, and ideological dimensions.

4. Literature Review

4.1. Relevant Study Analysis

This research conducted a comprehensive review of relevant studies, examining 31 selected works on hybridity in architecture (as detailed in the methodology section). These works were categorized into two groups: nine books focusing on the theoretical foundations and the spatial relationships of hybridity, and twenty-two peer-reviewed articles addressing the architectural and cultural dimensions of the concept. These texts were selected based on their direct relevance to the notion of hybridity in architecture and their frequent appearance in core academic literature.

The first group of studies on hybridity in architecture and urbanism provides diverse perspectives. Joseph Fenton’s Hybrid Buildings [5] represents an early exploration of hybridity, examining functional integration in mega buildings. In Hybrid Urbanism [2], Nezar AlSayyad analyzed hybridity at the urban level, clarifying the cultural, social, and political dimensions that contributed to its emergence in various cities. Patricia A. Morton’s [7] highlighted Western architects’ role in shaping colonial representations, and Smith and Leavy [26] emphasized hybridity as a dynamic interplay between local and global influences, challenging the notion of pure identities.

Hernández [6] emphasized the methodological approaches of postcolonial theory, particularly those of Homi J. Bhabha, in understanding architectural history and analyzing contemporary works. Guignery [16] examined hybridity’s theoretical, linguistic, and cultural dimensions, exploring its relationship to identity through the perspectives of scholars such as Anjali Prabhu, Mikhail Bakhtin, Robert Young, and Bhabha. Additionally, two publications by the a+t research group [14,22] explored hybrid buildings with mixed functions, highlighting their historical roots and the impact of globalization and urban demands. Fernández Per and Mozas [22] further analyzed hybridity by examining a set of buildings in New York City, determining the percentage of hybridity at the programmatic level.

The second group of studies reviewed in this research consists of 22 peer-reviewed articles and conference papers on hybridity in architecture. Oldenburg [37] introduced the concept of “third place”, a socially accessible space distinct from home and work, aligning with Bhabha’s “third space” and hybridity theories. Noble [31] examined hybridity in post-apartheid South African architecture, highlighting the insertion of foreign elements into local contexts. Loveday [38] explored hybridity within the structural layers of buildings, while Nissen [39] analyzed the transformation of public spaces into hybrid spaces where distinctions between public and private dissolve.

Beattie [8] examined hybrid spaces in Barabazaar, Calcutta, linking colonial laws to market space transformations. Lawson [40] studied hybrid spaces in libraries, showing how users continuously redefine spatial boundaries. Ikas and Wagner [18] analyzed border cities as third spaces where multiple identities coexist, echoing Waterhouse et al. [41], who argued that hybrid spaces arise from cultural conflicts at physical or imagined borders. Mehta and Bosson [42] examined Oldenburg’s third places in street life, while Adeyeye et al. [13] described hybridity in building adaptation strategies. Sargın and Savaş [43] explored hybridity in urban design through experimental projects integrating social and political realities. Pluta [28] analyzed multifunctional urban hybrid spaces, while Hart [10] discussed hybridity in the context of sovereignty and globalization. Kurniawan et al. [21] investigated the potential of Bhabha’s hybridity theories in shaping architecture and urban spaces in a Malaysian tin mining town.

Çelik and Akalın [30] identified four categories linked to the emergence of hybridity. Murrani [17] examined hybrid spaces formed along concrete walls in conflict zones, analyzing their spatial and social impact within the concepts of limits and third space. Thejas Jagannath [44] further expanded on this discourse by presenting Edward Soja’s urban interpretation of “Thirdspace” as a manifestation of hybrid environments. Krasilnikova and Klimov [45] explored permeable urban spaces as hybrids where public and private boundaries blur. Kassim et al. [32] investigated colonial-era stylistic changes, highlighting hybrid tectonic formations merging old and new materials. Zibung [15] linked hybridity to identity, emphasizing its role in shaping fluid and evolving identities. Nagy [46] differentiated multifunctional buildings from those using hybridization strategies, offering a broad perspective. Ptichnikova [9] viewed hybridity as an adaptive response to cultural globalization, resulting from the integration of local and global influences.

4.2. Critique and Gap Analysis

These studies have provided a detailed examination of hybridity relationship with architecture, highlighting the term’s inherent complexity, its extensions into diverse fields, and its intersection with various related concepts. These studies vary in focus: whereas studies (Agency, Leavy, Hernández [6], Guignery [16], Bhabha, Ikas and Wagner, Mclaughlin and others [18], Hart [10], Zibung [15]) focused on the theoretical background of the concept of global interconnectedness at the historical and current levels, studies such as (AlSayyad, Oldenburg, Nissen, Beattie, Mehta and Other, Pluta, Kurniawan et al., Murrani, Krasilnikov and Klimov) went to study the topic of hybridity in terms of its relationship to urban spaces between buildings and in cities in the period of colonialism, post-colonialism, and globalization. Hybridity, in terms of being a tangible material image, was the focus of studies (Fenton [5], a+t, Loveday [38], Kassim and others [32], Nagy [46]), which addressed the tangible aspects. The fourth group cooperated with the social, spatial, and symbolic dimensions (Morton [7], Nobl [31], Akalın Jagannath [44], Ptichnikova [9]) and how architecture reflects the social and cultural dimensions and hybrid discourses. While the last group (Sargın and Savaş [43]) addressed hybridity in terms of its connection to design methodology and design processes, whether at the level of architectural buildings or urban design.

Despite the wide range of studies addressing the concept of hybridity in architecture, they have often exhibited three main limitations: first, the absence of a unified analytical framework that systematically categorizes and distinguishes the manifestations of hybridity; second, the neglect of its ideological and cultural dimensions, in favor of focusing solely on form or function; and third, the reliance on descriptive applications of the concept within architectural case studies.

This study addresses these gaps by developing a comprehensive conceptual framework that classifies hybridity into tangible material indicators, dynamic interactive processes, and interconnected spatial dimensions. This model offers a flexible analytical tool to explore the relationship between hybridity, architectural meaning, and production, thereby contributing to the development of a more contemporary critical apparatus. This approach is further supported by Salama [47], who underscores the need for conceptual tools capable of engaging with the interaction between architectural discourse and socio-political contexts—positioning the current study as a significant contribution that moves beyond descriptive treatments towards a structured and applicable analytical model.

5. Developing a New Conceptual Framework for Hybridity in Architecture

5.1. Development of Indicators

Through an in-depth analysis of the literature and a systematic synthesis of both explicit indicators and recurring conceptual patterns associated with the concept, a new conceptual framework for hybridity in architecture was developed. These indicators were systematically derived from previous studies to establish coherent and integrated relationships that contribute to constructing a comprehensive theoretical model, supporting both conceptual clarity and practical application. This framework is structured around eight key indicators (see Table 1):

Table 1.

This table shows the conceptual framework indicators for hybridity in architecture.

- Form Hybridity: the hybridity indicator “Form” refers to a tangible appearance, manifesting through mixing shapes, combining elements, or representing mixed functions in the building mass. The first approach involves hybridity through material fragments, symbolic metaphors, or decorations tied to historical narratives [1,2,6,31]. The second approach extends to architectural and structural elements, such as columns and balconies [2,8,21]. While these approaches have historical roots, hybridity in the representation of mixed functions reflects modern urbanization and economic influences. The studies discussed here indicate that this type of hybridity can be expressed in several ways: through the explicit articulation of the building mass to reflect a mixture of functions (termed Graft hybrids), by concealing the functional mixture within the building mass (Fabric hybrids), or through the presentation of a unified, monolithic mass (Monolith hybrids) [5,48].

- Typological Hybridity: the “Type” hybridity index refers to the formal results of the hybridityization process, as it embodies a physical image of a set of interactions with different dimensions taking place in the background. Hybridity at the level of style can be observed through three indicators: first, as a result of mixing a local style with the architectural style of the colonizer or the dominant, which may occur due to modernization, hegemony, or economic, and cultural interaction [1,2,32,49]. Second, as a result of mixing a local style with a classical (Western) style, whose motives are symbolically related to social status and a representation of power [8,19,21,50]. Third, mixing the local style with the global, which is based on mixing multiple traditions and lineages under the influence of globalization concepts, and here continuous clashes arise between the local and the global [2,32,48,51].

- Program: from the critical discussions, it becomes clear that the “Program” indicator derives its depth from the historical repetition of the practice of combining multiple functions within a single structure. Hybridity at the functional program level is based on the necessity of diversifying the programs and uses of buildings and their spaces in response to the complexities imposed by the urban, cultural, and social environment [5,45,48]. In general, for the possibility of identifying two sub-indicators for the “Program” indicator, the first is the “Thematic program” where functions with similar themes are mixed, which achieves a kind of dependency and encourages an interaction between its parts while maintaining the uniqueness of each one. The second sub-indicator is the “Disparate Program” based on mixing separate entities into a single block [5].

- Mixing Use: hybridity in this context can manifest in three key forms: the integration of pre-determined uses, the blending of non-pre-determined uses, and the dynamic alternation of functions across different times of the day, such as day and night. Hybridity emphasizes the overlapping and sharing of spaces and functions within a building’s program, enabling flexible responses to current needs while anticipating future demands. This approach promotes the creation of open, adaptable spaces and fosters a social interaction by encouraging connections between strangers [22,49]. In this sense, hybridity can be seen as a response to Robert Venturi’s concept of the “difficult whole”, functioning as a dynamic system governed by contingency and indeterminacy. The third, the more advanced form of hybridity, adds complexity by allowing spaces to adapt to different functions throughout the day. For example, a space may serve one purpose in the morning and transform to meet a different need in the evening, offering temporal flexibility and maximizing utility based on occupancy patterns [22,46].

- User Mixing: this indicator highlights the continuous process of the interaction that defines hybridity, where it arises from the integration of diverse cultural and social practices within architectural spaces. This process unfolds through three key aspects: first, by creating porous and permeable spaces that invite access and engagement from both residents and strangers, fostering inclusivity [6,52]. Secondly, by preventing social and cultural differences from hindering the participation of different individuals or groups, but rather, it will support the building of relationships and challenge them at the same time [2,53]. The third is the recognition of the possibility of combining different images of architecture as imagined by the architect and its actual occupants [6,7]. Thus, architecture and its spaces are redefined as fields of power, activities, and continuous interactions in which users play a crucial role in shaping and reshaping these spaces, transforming them into living environments that reflect diverse identities and practices.

- Border Space: this indicator is primarily concerned with the location where hybridity occurs, at the point where two binaries are forced to meet. These boundaries can take various forms, whether material or immaterial, real or imaginary [41,54,55]. This indicator includes, first, the creation of border spaces that encourage community activities and allow for a high degree of personalization, and second, the process of breaching boundaries by recognizing the lack of a clear separation between the public and the private and the possibility of bringing one into the other, which contributes to the erosion of the boundaries between the two fields and the formation of an in-between space [2,39,52]. A compelling example of this overlap can be seen in the courtyard houses of Barabazar, India. These homes exemplify a fusion of public and private spaces, creating a unique form of hybrid architecture. The courtyards, though considered private, served multiple public functions such as ritual venues for family marriage ceremonies, death celebrations, confirmations, religious festivals, and discussions. The outer rooms (on the ground floor) surrounding the courtyard also served as offices, or kashbari, and were rented or lent as a courtesy for meetings, theatre rehearsals, and classes, blurring the lines between domestic and communal spaces [8].

- Multilayer: the changes that are implemented on the building over time will constitute a driver for the formation of hybridity in architecture through the accumulation of layers of use and reuse and the accompanying memories [2]. According to this vision, the concept of “Multilayers” can be understood in two aspects. The first involves the mixing and hybridity of different (different genes) layers within a site or building, which leads to identifying and distinguishing the nature of the previous occupation of the building and the nature of the current occupation of the building, Or by synchronizing all the layers, where multiple layers of building ruins dating back to different historical periods, are revealed and integrated into a new building that is part of this history, which gives the feeling of the slow flow of time. The second aspect represents hybridity based on re-composition, which is mainly based on the reuse of parts, elements, and strong structures of building structures that have lost their function or become fragmented over time for various reasons and are remixed in a context and meaning related to the new building.

- Control and Resistance: The “Control and Resistance” indicator reflects the represents the ongoing process of hybridity, as all attempts to control (whether by the dominant or marginalized party) over space are met with resistance that reproduces and redefines it. Many theorists, such as Homi K Bhabha, Paul Gilroy, Stuart Hall, Gayatri Spivak, and Nezar AL Sayyad, have pointed out that hybridity is not a fixed outcome but an evolving process of integration and fusion. However, hybridity also involves a dimension where synthesis does not fully occur and elements remain in tension creating conflict rather than harmony. This results in spaces being in a continuous state of flux, displacement, and competition. Such dynamics can manifest through the occupation of spaces or the use of architecture to project power and control. For example, in the 19th century, elites and officials adopted European architectural styles to assert authority and signify cultural dominance. Palaces and other grand structures became visual markers of this cultural conflict, symbolizing power struggles and social hierarchy [21,32]. Additionally, control and resistance are also enforced through laws, regulations, and planning policies that institutionalize differences. A notable example occurred in Basra after the British occupation in 1914. Captain Samuel Douglas Meadows, the city’s military governor, implemented urban development plans that enforced racial segregation, excluding original city areas and reserving the riverfront for government officials and merchants. British planners renamed streets with familiar British names like Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Street, erasing local identities and histories to assert colonial dominance. In this way, hybridity becomes a site of continuous negotiation.

5.2. Final Development of the Conceptual Framework of Hybridity in Architecture

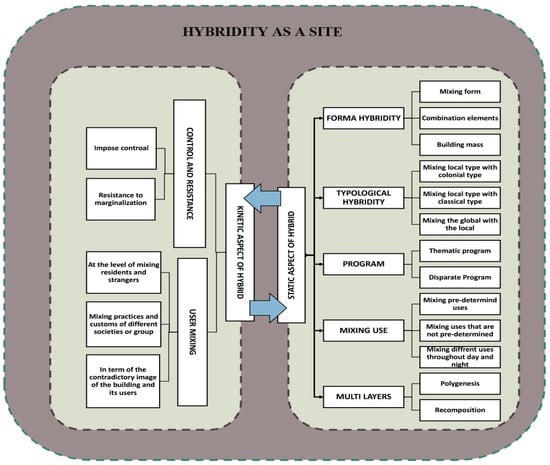

This section progresses to the final stage of developing a clear and comprehensive conceptual framework for hybridity in architecture. This framework is established by linking and integrating the primary indicators with the three dimensions identified in definitions of hybridity within postcolonial studies: hybridity as a result, hybridity as an ongoing process, and hybridity as a site. This approach enhances and provides a deeper understanding of the intricate layers of hybridity in architecture. Ultimately, this integration allows for the presentation of a complete and cohesive conceptual framework, fulfilling the primary research objective.

Hybridity as a site is represented spatially when cultures or situations are forced to interact, such as in post-colonial contexts or border areas—whether between nations, peoples, or spatial categories like public and private spaces. These interactions blur boundaries, creating spaces that absorb tensions and reveal hybridity at the intersection of dualities.

Hybridity manifests in two interconnected aspects. The “Static Aspect of Hybrid” encompasses the tangible results of hybridity, including blended architectural elements, functional programs, overlapping styles (local and global), adaptive reuse, and layered uses or histories. These material expressions are captured through indicators such as Form, Type, Program, Mixing Use, and Multilayering.

The “Kinetic Aspect of Hybrid” focuses on the intangible, ongoing interactions among users and communities from diverse cultural and social backgrounds. These interactions are shaped and mediated by laws, regulations, public opinion, and power dynamics, including those influenced by colonialism, globalization, or marginalized group negotiations. Indicators like Mix User and Control and Resistance exemplify this dynamic process.

These aspects are deeply interconnected: the Kinetic Aspect generates material forms (Static Aspect), while these static outcomes, in turn, fuel further interactions, sustaining a cycle of evolution and negotiation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

This figure shows the conceptual framework for hybridity in architecture.

6. Results

6.1. Application of the Framework: Baghdad University Case Study

This part focuses on achieving the third stage of this research, which is the application of the conceptual framework to a case study. In this context, it is essential to note that this research considers the University of Baghdad as a case study to explore how these hybrid concepts emerge in architectural form without assuming complete alignment with the designer’s original intentions. By analyzing the different dimensions of hybridity on the University of Baghdad campus, the usefulness of the framework in analyzing and interpreting hybrid architectural expressions will be demonstrated.

6.1.1. Introduction to Baghdad University’s Architectural Context

The University of Baghdad campus stands as a vital representation of modernist architectural heritage in the Middle East, embodying modernist principles while integrating local influences [56]. The university’s impact extended beyond Iraq, becoming a regional hub for scholars and contributing to Iraq’s intellectual and cultural leadership in the Middle East [57,58]. The architectural historian Mina Marefat emphasizes the University of Baghdad’s pivotal role in spreading architectural modernism beyond Europe and North America, during a period when Western ideas were widely adopted in the region [59]. This transitional era became a catalyst for architectural hybridity, blending efforts to solidify Baghdad’s role as the capital with aspirations for political independence and cultural renewal. Poppelreuter and Karim [60] note that these efforts were integral to positioning Baghdad as a center of modern architectural and urban development in the region.

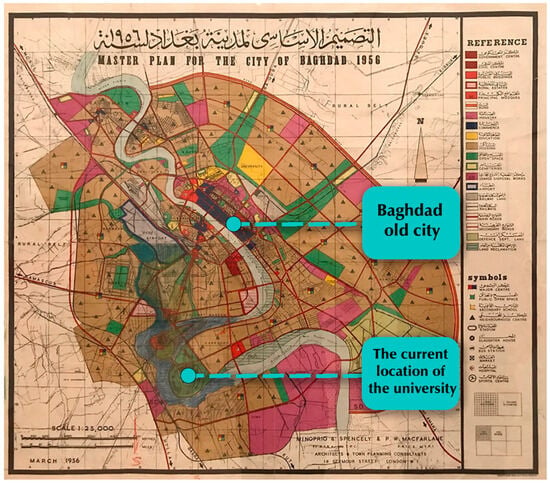

During the 1950s, the Industrial Development Board (IDB) played a pivotal role in Iraq’s modernization efforts, initiating studies aimed at advancing the nation’s economic, industrial, and educational sectors [61]. To bring this vision to life, globally renowned architects such as Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Gio Ponti, and Alvar Aalto were commissioned to design iconic structures [57,62,63] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The master plan of Baghdad City March 1956, by the British consultant London’s Minoprio & Spencely & P.W. MacFarlane [62].

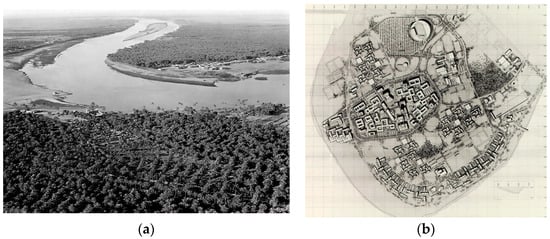

Walter Gropius began designing the Universi ty of Baghdad campus after visiting the site in November 1956 [62,64]. Beyond designing the physical structures, Gropius and The Architects Collaborative (TAC) developed the university’s architectural program, teaching principles, and multiple master plan iterations, culminating in three versions of the university between 1954 and 1981 [58,65]. His design emphasized flexibility to accommodate future needs, shaped by the site’s natural topography, the river’s curvature, and the region’s climate [64]. A key feature of the master plan was the integration of existing dikes or retaining walls, which TAC used as elevated walkways to link buildings and groups of structures. These dikes provided access to various entrance levels and terraces around the central plaza, adding spatial variety and complexity to the campus layout [64] (see Figure 3). Extensive research into traditional Iraqi architecture informed the design, combining local principles with modern construction techniques [65].

Gropius envisioned the campus as a low-rise, human-scale “small city”, inspired by traditional Arab settlements. Buildings were limited to three stories and densely arranged to create shaded, interconnected spaces that mimicked Baghdad’s narrow streets, fostering cooling and a sense of community [64]. The design featured courtyards, water basins, and fountains, creating a harmonious balance between built and open spaces. Shadow effects, achieved through cantilevers and recessed facades, introduced both rhythm and functionality to the architecture [66,67].

Figure 3.

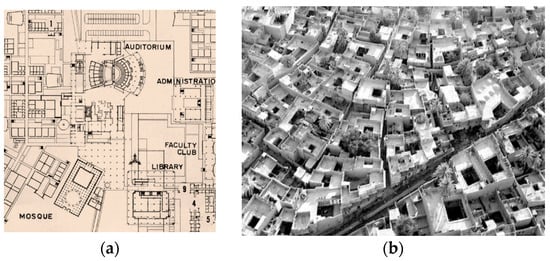

(a) The designated location of the University of Baghdad prior to its construction in 1932 AD. Source: Baghdad university museum archives; (b) Master plan of University of Baghdad 1957. Source: Wikimedia [68].

6.1.2. The Campus Design and the Context

The Canadian Centre for Architecture CCA portfolio of 1960 shows that the spatial structure of the campus was divided into three rings (zones) representing three main functions, including common, academic and residential areas, arranged centrifugally, with the degree of enclosure of buildings increasing as we move from the center towards the surrounding Tigris River [58,69]. The first zone (closest to the center) contained the academic buildings, the second zone contained student housing, and the third zone contained the sports fields.

The First Zone: At the core of the University of Baghdad campus, a central plaza surrounded by key structures—such as the library, lecture hall, theater, Mosque, and tower of faculty offices—formed the cultural and academic heart of the university (see Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6). This asymmetrical plaza, set among palm trees and green spaces, served as a hub for daily student activities and represented the university’s public life, blending academic and cultural functions [58,64].

Figure 4.

(a) Site plan of campus center. Source: architectural record archive 1959. (b) Courtyard pattern in the traditional fabric of an old neighborhood unit in Baghdad. Source: Library of Congress [70].

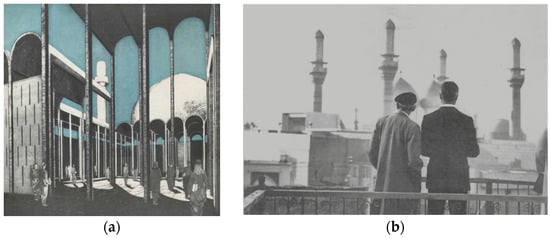

Figure 5.

(a) View from the plaza leading toward the mosque. Source: architectural record archive. (b) Gropius and Mc Millen in front of the great Shiite mosque at Kadhimiya, Baghdad. Source: Mc Millen, Louis, ‘The University of Baghdad, Iraq’, in The Walter Gropius Archive, ed. by Alexander Tzonis (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991).

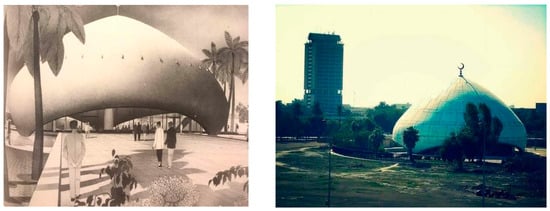

Figure 6.

The university mosque was initially a traditional design but it morphed into a large dome supported on three points suspended over a circular water basin to reflect light. The exterior was to have glazed turquoise tile and a rectangular praying area extending from outdoor to indoors. Source: Iraqipalac [64,69,71].

The academic area grouped faculties of science, engineering, and humanities around smaller green spaces. Flexible scheduling of shared facilities encouraged interdisciplinary dialogue and allowed for future expansion. Elevated walkways and shaded paths connected all buildings, creating a cohesive network, while a surrounding ring road minimized vehicle access, adhering to Bauhaus principles of functional unity [64].

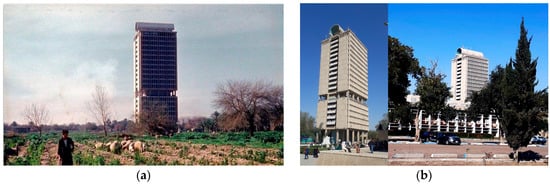

The third prominent building in this area is The Tower: a 20-story faculty office tower, the only high-rise in the campus skyline (see Figure 7). This tower was added after General Abdul Karim Qasim came to power in Iraq following the assassination of King Faisal II on 14 July 1958. Qasim specifically requested a tall building in the central square, reportedly so he could see it from his Ministry of Defense office miles upriver or to ensure public visibility of the university landmark [58,64]. As Sudjic (2005) [72] notes, high-rise buildings were often a priority for wealthy regimes eager to present themselves as modern. Thus, Qasim’s request for the University Tower can be interpreted as an assertion of his authority and an attempt to frame his power within Baghdad’s evolving skyline [61].

Figure 7.

(a) A photo of the university of Baghdad tower taken in 1967, showing the surrounding project context in the foreground, including orchards and agricultural areas. Source: Baghdad university museum archives. (b) The deep-set windows of the tower reflect sensitivity to the local climate, while the structure stands as a prominent symbol of modernization in education and architecture during the post-independence era. Source: observation survey.

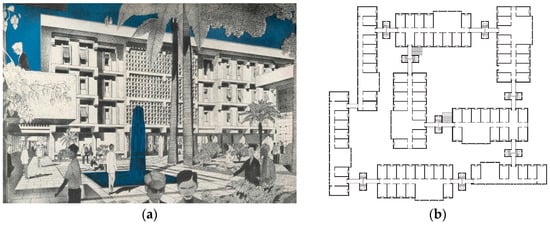

The Second Zone: The second zone of the University of Baghdad campus included medium-rise dormitories for male and female students, originally planned for 5600 male and 2400 female residents, though later converted into educational facilities [58]. The design considered social and cultural norms, separating male and female dormitories into distinct courtyards for privacy (see Figure 8) [62,64].

Figure 8.

(a) Dormitory building. Source: [58,73]; (b) dormitory building—upper floor plan. Source: [73].

The Third Zone: In this zone, two main clusters can be mentioned, the sports facilities and the faculty housing, which have not been built. Gropius chose the location of the stadium away from its center and close to its entrance, assuming that it would serve not only the campus but also the city and the community surrounding the campus in the future [58,73]. The design team located these residential areas according to the position of the existing dams, which were built during the late Ottoman modernization process to regulate the flow of water and prevent flooding [58]. The master plan for the campus also proposed a location for the elementary school directly opposite the central area and along the opposite edge of the campus, away from the central facilities, which would facilitate the school’s opportunities to serve the university and the surrounding community and help create an opportunity for integration with the surrounding campus community in the future [73].

6.1.3. Analysis Using the Framework

The conceptual framework of hybridity in architecture is applied to the designs of the University of Baghdad campus, created by one of the most prominent pioneers of modern architecture, Walter Gropius (see Table A1). Each indicator is analyzed to uncover how hybridity manifests through the architectural and spatial strategies employed in the campus design. This detailed step-by-step examination provides an in-depth exploration of the multidimensional layers of hybridity embedded in Gropius’s visionary project.

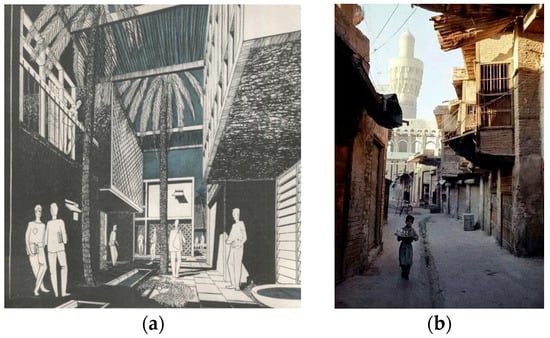

Hybridity at the Form Level: Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad campus exemplifies formal hybridity through the integration of modern and traditional architectural elements. Surface treatments blended exposed concrete with woven local materials, creating facades that reflect both global modernism and local aesthetics. Gropius innovatively combined traditional shading elements, like mashrabiyas, with modern sunbreaks to adapt to the cultural and climatic context (see Figure 9). This approach brings hybridity to the forefront, avoiding the replication of historical forms while fostering a unique architectural identity.

Figure 9.

(a) Typical dormitories. Note that close spacing of building and overhangs provide shade. Source: architectural record archive1959; (b) Baghdad, Iraq 1969. Source: photo by Ferdinando Scianna.

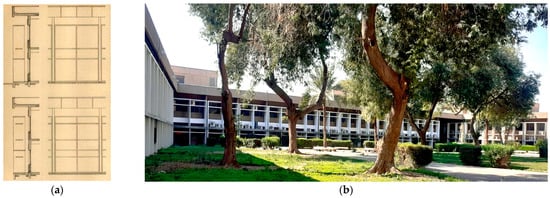

Hybridity at the Type Level: Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad showcases architectural hybridity by blending local and global influences, showcasing a profound post-colonial interaction. Surface treatments blended exposed concrete with woven local materials, creating facades that reflect both global modernism and local aesthetics. Gropius innovatively combined traditional shading elements, like mashrabiyas, with modern louvers to adapt to the cultural and climatic context (see Figure 10). More broadly, Gropius’s vision of a “small city” is realized through dense, low-rise buildings, traditional courtyards, and shaded pathways. This design not only mirrors Baghdad’s historic urban fabric but also incorporates modernist principles. This approach embodies hybridity by transcending the mere replication of historical forms, instead fostering a distinctive architectural identity that bridges tradition and modernity.

Figure 10.

(a) Above are shown alternates of precast sun-shade louvers, each designed to break down the sun according to varying sun angles resulting from different orientations. Source: architectural record archive 1965; (b) design of Baghdad central station. Source: observation survey.

Hybridity at the Functional program Level: By applying the conceptual framework of hybridity in architecture, Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad campus did not show any indications of a hybridity at the functional program level.

Hybridity at Mixed use Level: Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad reflects hybridity through mixed use, creating flexible spaces that accommodate both academic and non-classroom activities. These shared spaces are not designated for specific programs or departments. This approach fosters interaction across fields of knowledge, transforming the university into a collaborative and adaptable center for learning.

Hybridity at the Multilayered Level: This is evident in Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad, which blends modern campus planning with the site’s historical and cultural context. Gropius integrated natural elements like palm orchards, dams, and retaining walls into courtyards, elevated walkways, and multi-level entrances (see Figure 11 and Figure 12). These features preserved the site’s agricultural and cultural history, evoking memories of daily life and reinforcing local identity. Rather than erasing the past, the design embraced it, creating a hybrid texture rich in layers of history and local consciousness.

Figure 11.

Elevated streets and shaded paths form a seamless network, weaving together the learning spaces into a cohesive whole. Source: observation survey.

Figure 12.

The team also suggested an irrigation network and a sewage treatment system so that bacteriologically safe water could be used for the irrigation of the campus landscape. Source: the official page of the College of Political Science at the University of Baghdad [74], and Wikipedia [75].

Hybridity at the Resistance and Control Level: This reflects hybridity as an ongoing process in Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad, showcasing architecture as both a tool for imposing control and resisting marginalization in a post-colonial context. The campus’s location on the Karada Peninsula, separated from Baghdad by the Tigris River, mirrored colonial practices of isolating projects from local communities. This separation aligned with Iraqi elites’ vision of development and integration into the modern world.

The architecture served as a tool of control, with the Iraqi government adopting American modernist styles to assert authority and replace British colonial influences. Urban planning reinforced Western educational philosophies while fostering state-building efforts. However, Iraq reasserted control post-colonially, modifying the campus to reflect national identity. Additions such as the University Presidency Tower and Gate symbolized resistance to colonial influences and asserted Iraqi sovereignty. These steps highlight hybridity as a process blending control, resistance, and identity.

Hybridity at the Mixing users Level: Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad exemplifies hybridity through the mixing of users, fostering a continuous interaction between individuals from diverse backgrounds. The campus design encouraged meetings and communication among university members and the surrounding community. The central area, with its cultural spaces, acted as a meeting point for students and the public, while courtyards facilitated interactions among students from various religious and cultural backgrounds.

The campus’s permeability and accessibility further enhanced hybridity, with markets and a primary school at the borders and cultural spaces like the library and theatre at its core. These spaces allowed for interactions between academics and the Baghdad community. Elevated corridors and shaded pathways connected buildings, creating hybrid spaces for collaboration across disciplines. Additionally, courtyards supported diverse social and cultural activities, promoting interactions and cultural exchange.

Hybridity at the Border Space Level: Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad reflects hybridity through active edges and the integration of public and private spaces. The university’s borders, featuring schools and markets, serve as active zones that bridge the campus and local community, fostering social interaction and hybrid spaces. Semi-private spaces, such as courtyards and corridors, balance privacy with interaction, encouraging engagement between departments and with public spaces in the academic core. This design enriches both university life and community connections.

6.1.4. Results Summary

Applying the conceptual framework of hybridity in architecture to Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad campus shifts the focus from the Western system of classifying architectural output based on the building’s image, materials, and construction techniques, to linking the building to a much broader context that includes the cultural, political, and social aspects that are inherent in their production. This framework thus allows for the disclosure of the ways in which buildings respond to people and users as individuals or groups. At the same time, the application of the framework reveals the cultural, social, and ideological aspects of interactions between different groups in post-colonial Iraqi society on the one hand, and Gropius, who seeks to represent modernity according to his vision and interpretation of the path of modernization that postcolonial countries must follow. In summary, the results of applying the framework in terms of the three aspects of hybridity in the design of the University of Baghdad campus can be summarized as follows:

The Static Aspect of Hybrid

The conceptual framework proves useful in revealing the dimensions of hybridity in Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad campus. It highlights how Gropius combined modern architectural techniques, rooted in his Bauhaus background, with traditional local elements. The integration of exposed concrete with local materials such as brick and the blending of modern sunbreaks with traditional shading devices like the mashrabiya, exemplify “Form Hybridity”, where imported and indigenous aesthetics intersect to serve both functional and cultural goals. While these solutions addressed environmental challenges such as thermal comfort, the framework also reveals a deeper dynamic: hybridity was used as a pretext for prioritizing technological advancement and modernity over local traditions, thereby marginalizing traditional architectural identities [66,67,76,77].

The framework reveals how Gropius’s design reflects hybridity and its tensions. His modernist philosophy fostered “Typological Hybridity” by merging traditional courtyard forms with modern materials like concrete and steel. These spaces addressed the climate, preserved the human scale, and encouraged social interaction—unlike colonial models, which Chris Abel sees as driven by control through adaptation [1]. The collaboration with Iraqi architects from the TAG Group—particularly Mahdloom and Munir—likely contributed to embedding local cultural awareness in the project.

Furthermore, the shared academic spaces, designed with spatial openness and adaptability, reflect the concepts of “Mixed Use” and “User Mixing”, enabling interdisciplinary interactions while dissolving rigid spatial hierarchies. This spatial flexibility aligns with Aurora Fernández Per’s [22] vision of hybrid buildings that promote flexible use. However, while hybridity created opportunities for spatial innovation, Gropius’s dominant emphasis on modernity often threatened to obscure local materials and identity—a concern highlighted by theorists such as Anthony King [78] and Edward W. Said [79]. Thus, the design reveals hybridity as a double-edged condition—facilitating cultural synthesis, yet introducing tensions between preservation and transformation.

The Kinetic Aspect of Hybrid

The conceptual framework of hybridity effectively reveals the multidimensional nature of Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad campus, particularly highlighting its role as an arena for resistance and control. Gropius’s approach combined design solutions rooted in interpretations of Iraqi architecture and cultural heritage with a Western vision of modernity. However, this integration also served as a tool for cultural, ideological, and political control, positioning architecture as a symbol of power. By blending these elements, Gropius’s design both responded to and fueled divisions within Iraqi society: modernist proponents, often Western-educated architects, supported modernization; traditionalists sought a return to local architectural styles; and others upheld British colonial classical architecture as a symbol of royal authority [19].

This tension underscores how Gropius’s architecture mediated resistance and control. His design aimed to liberate Iraqi architecture from British colonial influence while promoting a Western-oriented modernization. The concept of hybridity reveals his work as both a transformative force and a tool of authority. The university tower, added at General Qasim’s request, became a dominant visual symbol of the new regime and a deliberate assertion of state power—exemplifying the “Control and Resistance” indicator within national modernization efforts [58,80].

By introducing the “city within a city” concept, Gropius combined Baghdad’s traditional urban fabric with modern academic structures, using courtyards to facilitate collaboration and interaction. While promoting open, democratic spaces, this approach also reinforced subtle forms of dominance through the spatial organization and material symbolism [66,67]. Thus, hybridity within the kinetic dimension emerges as both a tool for democracy and a means of strategic control.

Hybridity as a Site

The conceptual framework of hybridity reveals the University of Baghdad campus as a hybrid site where multiple interactions occur, reflecting Homi K. Bhabha’s “third space” concept [50]. Gropius designed active edges on the campus periphery, placing markets and schools to bridge traditional boundaries and foster interaction between the academic and local communities. These spaces created opportunities for cultural and social exchange while maintaining some academic boundaries, reflecting a postcolonial negotiation between cultural hegemony and integration.

The inclusion of semi-public and semi-private spaces between campus departments and public access to the central cultural areas further supports hybridity as a site. This approach, as noted by critics like King [78] and Hall [81], enhances multiculturalism and social interaction. Rather than enforcing separation, Gropius’s design fosters dynamic, hybrid spaces that redefine urban interaction, blending academic and local cultures in ways that challenge traditional hierarchies.

7. Discussion

7.1. Contextualizing Research Findings in the Literature

This section places the proposed framework within a broader academic conversation, showing how it builds upon and extends previous studies in the absence of a comprehensive conceptual model for hybridity in architecture. By offering a systematic and structured approach, this study moves beyond conventional perspectives on hybridity by:

- Expanding Jevremović’s [3] view of hybridity as a transitional and unstable condition by offering a structured analytical framework that allows for its examination as an organized process applicable across different historical and cultural contexts;

- Building upon Fenton’s [5] classification of hybrid buildings based on functional integration but extending the analysis to include socio-political and contextual forces rather than limiting hybridity to formal structures;

- Challenging Abel’s [1] static interpretation of hybridity which primarily focuses on European stylistic shifts in colonized territories. By demonstrating that hybridity is a fluid and evolving phenomenon shaped by power structures cultural identity and architectural adaptation, this study provides a more comprehensive framework that accounts for the transformation of indigenous architectural traditions in response to colonization;

- Expanding AlSayyad’s perspective [2], by introducing a structured framework to assess hybridity as both an architectural process and outcome, building on his view of urban hybridity shaped by migration and colonial legacies.

Compared to previous research, this study introduces a structured and multidimensional framework that addresses key gaps in architectural hybridity research, particularly those related to analytical methods and real-world applications, specifically the following:

- It incorporates multiple dimensions—formal, functional, spatial, and ideological—going beyond earlier approaches such as Fenton [5] and AlSayyad [2], which tend to focus on singular aspects like functional integration or cultural symbolism.

- It offers a systematic and indicator-based method for identifying hybridity in design, in contrast to the predominantly narrative or qualitative discussions in works like Morton [7] and Smith and Leavy [26].

- It extends the postcolonial architectural analysis by connecting hybridity to architectural adaptation, modernization, and resistance—moving beyond the abstract or discursive nature of studies like Hernández [6] and Guignery [16].

- It grounds the theoretical framework in a real architectural case—Walter Gropius’s University of Baghdad—offering a practical model of how hybridity materializes in spatial and material design, which is often missing in conceptual texts such as Ptichnikova [9] or Zibung [15].

7.2. Insights from the Baghdad University Case Study

The application of the proposed conceptual framework of hybridity to Walter Gropius’s design for the University of Baghdad reveals several new insights that go beyond conventional interpretations of his work. These insights reflect the depth of Gropius’s hybrid approach and demonstrate how his designs were shaped by social, political, cultural, and environmental factors. Below are the key points derived from the framework:

- Hybridity as a Strategic Tool for Modernization: the framework (see Table A1) highlights how Gropius employed hybridity as a strategic tool for modernization without detaching from cultural identity. This ideological dimension of hybridity is evident in the Iraqi government’s adoption of American modernist styles to reshape its authority and replace British colonial legacy, as reflected in the framework’s “Control and Resistance” indicators. On another level, Gropius’s integration of local materials such as brick with modern technologies like ribbon windows and exposed concrete exemplifies “Typological Hybridity”, “specifically through the Mixing the global with the local”. This aligns with Loureiro’s observation [82] that Gropius deliberately rejected the rigid application of the International Style—which often produced homogeneous buildings worldwide—in favor of culturally rooted expressions. His preference for ribbon windows and exposed concrete as “primitive elements” to be localized further underscores this hybrid approach. This hybridity also supported the campus’s sustainability, aligning with Sonetti’s insights [83] and with Gropius’s own assertion that his aim was to include every vital element of life, rather than adhere to a narrow and dogmatic vision [82].

- Hybridity as a Response to Postcolonial Power Dynamics: the framework examines the relationship between architecture and politics through two main pathways. The first is “Imposing Control”, exemplified by the construction of the University Tower as a tangible symbol of power, reflecting the new regime’s intent to assert its presence on the city’s skyline as a post-revolutionary emblem of authority. This aligns with Gropius’s statement that modern architecture should not begin with the public but rather with the elites capable of embracing change [84].The second pathway involves “Reasserting Control/Mimicking Dominance”, aimed at transcending colonial models by integrating local materials such as brick and traditional courtyard designs with modern architectural technologies—falling under the sub-indicator of “mixing local type with global models”. This hybrid approach serves a dual purpose: it rejects colonial architecture, once a symbol of cultural and political domination, while also promoting a new national identity aligned with modernity and progress [85]. This reading illustrates how hybrid architecture, as defined by the framework’s indicators, functions as a dual mechanism—both a form of resistance to prior hegemonies and a tool for reproducing authority within new political arrangements.

- Hybridity in Political and Cultural Identity: The framework reveals how Gropius’s work appears politically charged, reflecting Iraq’s post-revolutionary aspirations to assert cultural independence from British influence while embracing modernity. He found himself aligned with General Abdul Karim Qasim, as both viewed socialism as a means to realize their visions. Gropius regarded the Soviet Union as the only state that had successfully liberated land from private property constraints, enabling the development of healthy, sustainable, and economically viable urban spaces for the public good [73]. The “Tangible Symbols of Power” indicator is manifested in the design of the Presidency Tower, which served as a visible symbol of state dominance and occupied a central position in the campus skyline, reinforcing the regime’s ambition to project a modern national identity. Meanwhile, the “Impose Control” indicator is reflected in Gropius’s formulation of the university’s educational system, which was designed as a tool for shaping the consciousness of future generations in line with modernist ideals. This approach positioned architecture not merely as a physical product but as a mechanism for reproducing authority and directing societal transformation. This interpretation aligns with Marefat’s [62] argument that Gropius’s work at the University of Baghdad was not just a modern hybrid expression but was deeply rooted in nationalist political agendas.

- Hybridity as an Ongoing Negotiation Process: the framework demonstrates that the design of the University of Baghdad evolved through continuous negotiations with local architects and political leaders, reflecting hybridity as an indicator of “ongoing interactive processes” within the framework’s dimensions. This dynamic interaction underscores the adaptability of the design to local political and cultural contexts. This dimension is further evident in the “mixing of practices and customs of different communities”, as the local design team engaged in an architectural production process that merged Western standards with Iraqi social values. Gropius avoided cultural appropriation by prioritizing dialogue and involving local architects, rather than imposing pre-defined Western forms—although the final outcome still reflects the dominance of the modernist aesthetic. This aligns with Crinson’s thesis—supported by others—that modernist architecture in postcolonial contexts played a dual role: symbolizing modern independence on one hand and reinforcing elite cultural dominance on the other [21,32,80]. Over time, external urban pressures diminished the effectiveness of hybrid spaces at the University of Baghdad, weakening the “User Mixing” indicator. Al-Akkam [86] and Khalaf and Ibrahim [87] attribute this decline to inadequate planning and fragmented movement networks, which compromised spatial cohesion and reduced opportunities for social interaction. While hybrid spaces can foster cultural exchange, their long-term viability depends on integrated planning strategies that are responsive to evolving urban conditions.

- The University as a Hybrid City within a City: the framework reveals hybrid layering in Gropius’s design—both in terms of the site and urban fabric—aligning with the “Multi-layering” indicator. He preserved original site features, such as irrigation dams and palm orchards, embedding them into the campus layout to balance spatial memory with a modernist vision. This also reflects the “Border Space” indicator. The campus was designed to facilitate pedestrian movement and spatial accessibility, much like a traditional city, aligning with sustainability principles as confirmed by studies by Matloob [88] and Sonetti [83]. Al-Akkam [86] identifies changes resulting from security measures, infrastructure modifications, and urban expansion, all of which have influenced the relationship between the campus and its surrounding urban fabric. These shifts underscore that campus hybridity is a dynamic process shaped by external socio-political and urban forces, rather than a fixed design outcome.