1. Introduction

In Tuvalu—a low-lying Pacific nation already contending with rising seas, changing weather patterns, and stressed natural systems—environmental stewardship is not just policy talk; it is part of daily life. From the shoreline to the classroom, climate change is shaping how people live, work, and think about the future. Education is often seen as one of the most powerful tools for preparing young people to face these challenges. However, even with national policies that promote sustainability and resilience, there is still a gap between what is promised on paper and what is actually taught in schools [

1,

2].

This commentary offers a personal and professional reflection on that gap, drawing on the lead author’s dual experience as a doctoral researcher and Director of Environment for Tuvalu. It builds on an earlier publication [

3], which analyzed the extent to which Tuvalu’s national education and environmental policies are aligned with each other and with regional and global sustainability frameworks. That study found significant inconsistencies across policy domains, highlighting the need for better horizontal and vertical policy coherence to effectively integrate Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE) into the national curriculum. In this piece, the focus shifts from policies to practice—how ESE is represented in school curricula and why that matters.

National frameworks like the Tuvalu Education Strategic Plan III (TESP III, 2016–2020) and the Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF, 2019) talk about preparing students for climate challenges. However, studies show that environmental content is inconsistently included in the actual curriculum—especially in primary and lower secondary levels [

3,

4]. Even when it is there, ESE is often confined to upper-level electives like geography and biology, which only a fraction of students ever take [

1]. That is a real problem in a country where high dropout rates mean many students finish their schooling by the end of primary education [

5,

6].

What is more, Tuvalu’s traditional ecological knowledge—wisdom rooted in generations of environmental care—is rarely reflected in formal curricula. This is a missed opportunity not just for cultural continuity, but also for teaching locally grounded, climate-relevant skills [

7].

This is a critical reflection—grounded in practice—on how climate-vulnerable countries like Tuvalu can rethink what and how we teach. By sharing Tuvalu’s experience, this article intends to spark conversation across the Pacific and other Small Island Developing States (SIDS) about making ESE more inclusive, more relevant, and more impactful.

2. Methodological Positioning and Approach

This commentary draws on a blend of document analysis, professional experience, and insights gathered through years of involvement in Tuvalu’s education and environmental policy sectors. Rather than offering new empirical research, the reflections presented here are grounded in a close reading of national curricula, education policy frameworks, and environmental strategies developed between 2007 and 2019 [

1,

2,

8].

The primary sources examined include the Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (2019), the Tuvalu Education Strategic Plan III (2016–2020), and relevant syllabi for subjects most closely aligned with Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE)—specifically, basic science, social science, geography, and biology subjects [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. These subjects were selected because they contain the clearest intersections with environmental and climate education themes. Geography and biology, however, are offered only as optional subjects in upper secondary school, which limits their reach for the broader student population [

3] (see

Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Materials). This has potential repercussions in how future environmental stewardship is framed and practiced by future generations.

Many of the documents used in this analysis were accessed through the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (MEYS), the Department of Environment (DoE), and the Department of Climate Change (DCC). Some were publicly available online, while others were obtained directly from relevant departments. Where possible, we reviewed the most recent versions in use for policymaking and school-level implementation [

22,

23,

24].

Our approach also builds on a previous study published as Part 1 of this series, titled Environmental Stewardship Education in Tuvalu: The Role of Policy Alignment [

3]. That work involved a more detailed critical discourse and content analysis of government policy documents to explore the conceptual alignment between education and environmental goals. Rather than duplicate those methods here, this article focuses on how those policy ideas are being (or not being) reflected in actual classroom practice.

These reflections are further informed by firsthand knowledge of government operations and curriculum development in Tuvalu. This ‘insider’ perspective provides context for interpreting how national education goals translate into everyday teaching practices. By bringing together documentary evidence and practitioner experience, the goal is to offer a grounded perspective on how ESE could be more effectively embedded in Tuvalu’s education system.

3. Observations and Reflections on Curriculum Delivery

3.1. Early Dropout and Missed Opportunities

One of the most pressing challenges in Tuvalu’s education system is student retention. While primary education is compulsory and widely accessed, many students do not continue to the upper levels of secondary education. In 2022, for example, only 66 students remained in Year 13 from a cohort of 244 that started in Year 1—a 73% attrition rate [

25]. These numbers, detailed in

Table 1, reflect a hard truth: if ESE is primarily taught in the later years of secondary school, most young people will never encounter it.

Given these realities, it becomes clear that ESE needs to be introduced much earlier. Primary education is not just a starting point—it is often the only point. Embedding core environmental concepts during these early years, especially through experiential strategies, could have a far greater reach and impact [

4,

26,

27,

28]. Young children are naturally curious and open to new ideas. By engaging them in sustainability topics from the outset, we can foster the values and habits that support lifelong stewardship.

Table 1.

Attrition rates in primary and secondary schools.

Table 1.

Attrition rates in primary and secondary schools.

| Primary School | Secondary School |

|---|

| ECCE | Yr 1 | Yr 2 | Yr 3 | Yr 4 | Yr 5 | Yr 6 | Yr 7 | Yr 8 | Yr 9 | Yr 10 | Yr 11 | Yr 12 | Yr 13 | Total |

| 718 | 244 | 222 | 248 | 232 | 219 | 225 | 221 | 243 | 203 | 173 | 148 | 98 | 96 | 3260 |

| | | −9.0 | +11.7 | −6.50 | −5.60 | +2.7 | −1.80 | +10.0 | −16.5 | −14.8 | −14.5 | −33.8 | −32.7 | - |

The low uptake of optional subjects like geography and biology at Motufoua Secondary School (the only government-owned institution in Tuvalu) further compounds this issue. Only a small percentage of students choose these subjects—14–27% depending on the year—meaning ESE is effectively limited to a minority of students in Years 11–13. The message is clear: waiting until upper secondary to introduce ESE is a strategy that misses most learners.

3.2. Reflections on Primary and Lower Secondary Curriculum (Years 1–10)

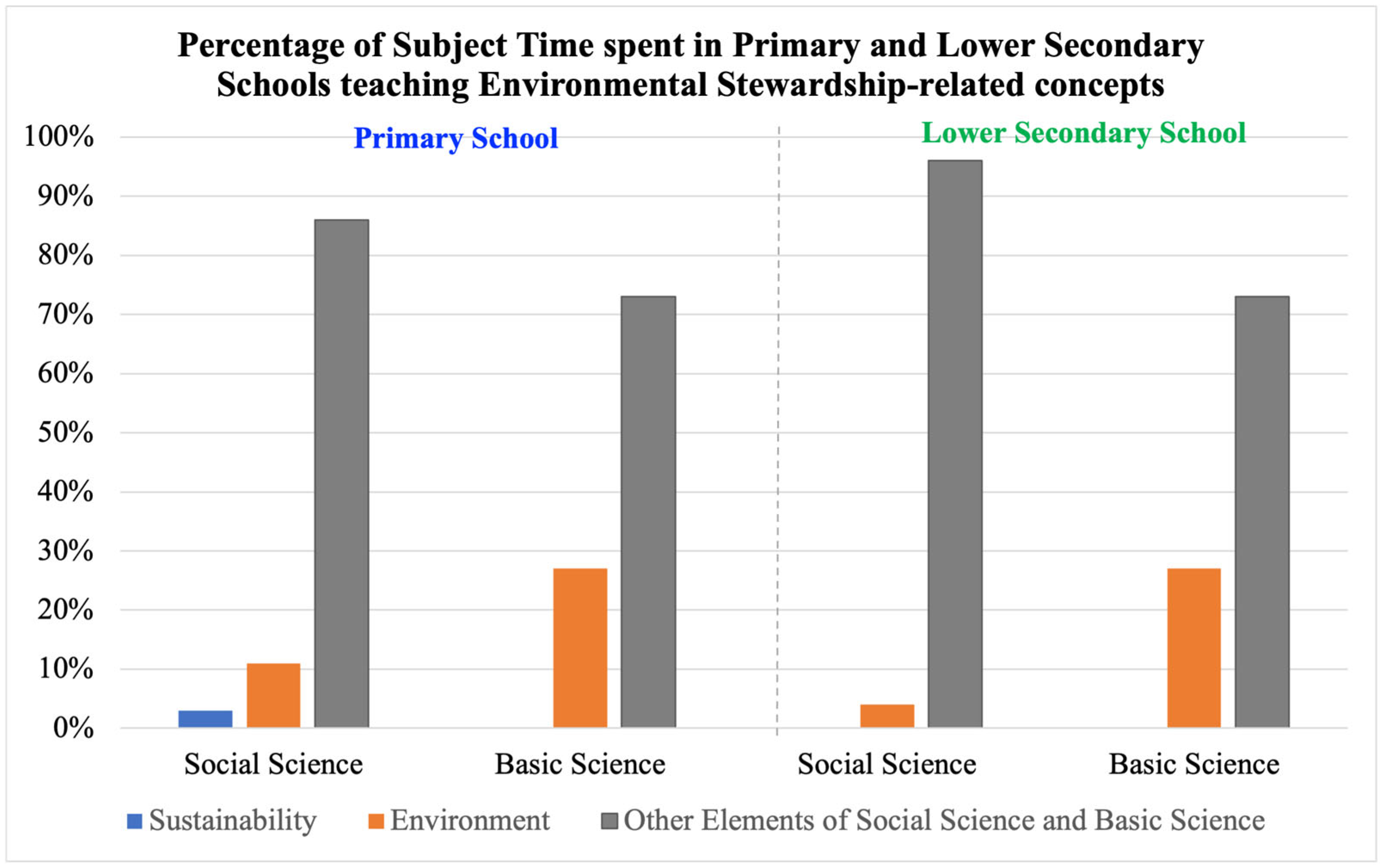

When we looked more closely at the syllabi for primary and lower secondary education, we found that environmental topics do appear—but they are inconsistently integrated and often limited in scope. In Years 6–10, ESE-related content is primarily found in social science and basic science, and even then, it is not always labeled explicitly as environmental stewardship. Topics such as sustainability, climate change, or biodiversity are sometimes present, but often as background themes rather than focal points.

The results indicated a misalignment between the intended policy outcomes and the actual content delivered in schools. ES and environmental stewardship-related concepts such as sustainability, the environment, climate change (CC), biodiversity and disaster risk reduction (DRR) are delivered through national curricula in ten elementary and two secondary schools with English as the medium of instruction [

30]. As a result of the review of the TESP II 2011–2015 to formulate the TESP III 2016–2020, a key recommendation was to improve the curriculum and assessment. This recommendation coincided with the formulation of the first-ever Tuvalu National Curriculum and Policy Framework (TNCPF) in 2013, which proposes the adoption of an outcome-based curriculum [

8] (p. 14). Further work must be done to transform the TNCPF into syllabi, teaching guides, and student handbooks aligned with an outcomes-based curriculum from preschool to year 13 [

31] (p. 33).

As shown in

Figure 1, the total teaching time allocated to environmental themes is small. Out of hundreds of instructional hours across multiple years, less than 2% is spent on topics linked directly to environmental stewardship. For instance, in Year 7, only four weeks in Term 2 are dedicated to ESE-related content, as illustrated in

Table 2. This reflects a broader pattern: while policy language highlights sustainability, the curriculum tells a different story.

Even the TNCPF encourages outcome-based learning that would support environmental education, but much of this remains to be translated into practical classroom tools—like lesson plans, student handbooks, or teaching guides. Without this, good intentions stay on paper.

3.3. Reflections on Upper Secondary Curriculum (Years 11–13)

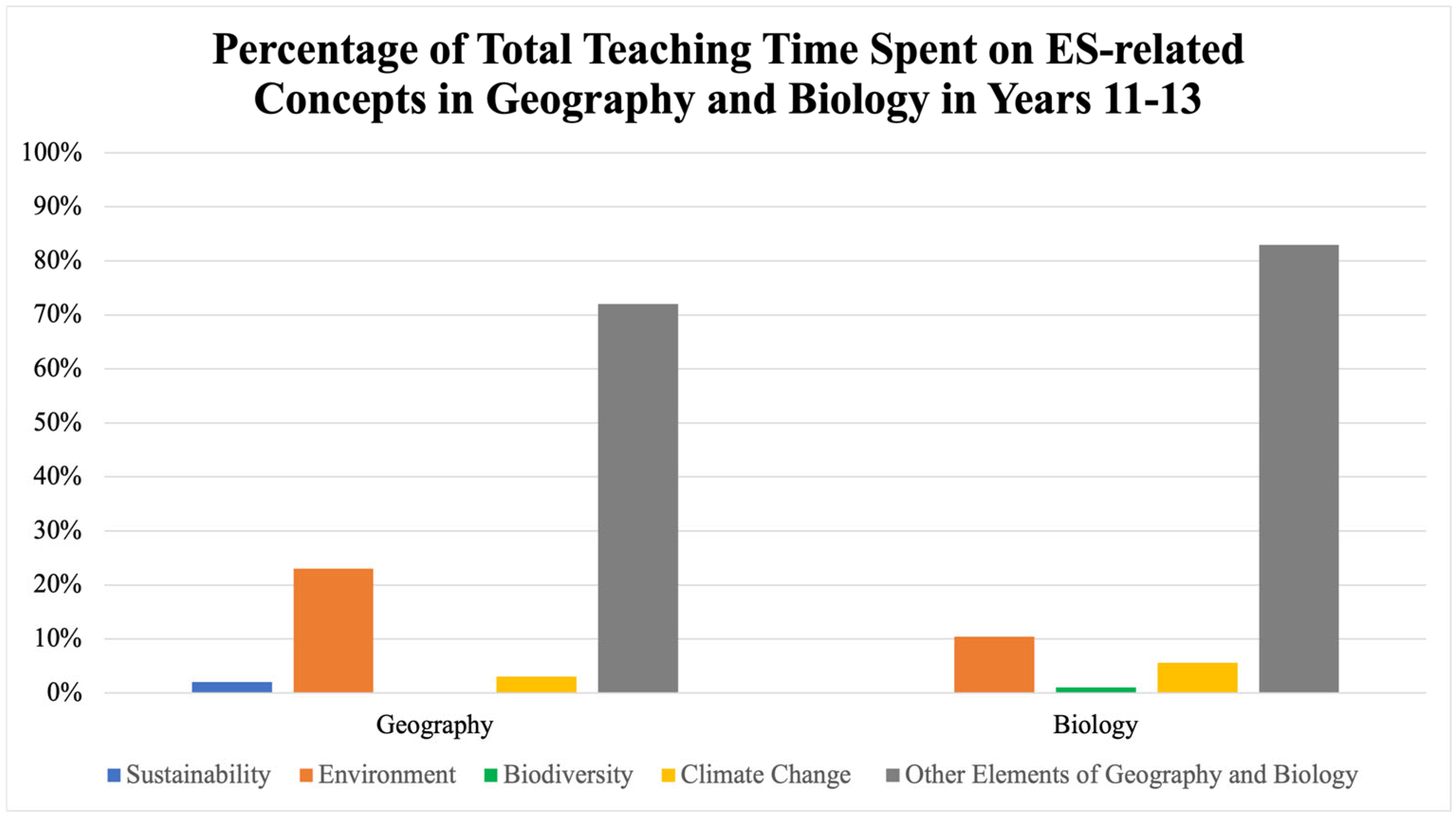

At the upper secondary level, subjects like geography and biology [

22,

23] do engage more deeply with environmental issues. These are the only two subjects in which ESE is meaningfully addressed, and even here, the content has limitations.

Figure 2 shows that while some time is allocated to topics like climate change and conservation, biodiversity appears just once in the Year 13 curriculum—and disaster risk reduction is notably absent.

It is worth noting that the inclusion of climate-related content at this level is largely due to the influence of regional partners like the Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s (SPC) and its Educational Quality and Assessment Programme (EQAP). This shows that external frameworks can shape local education offerings—but also raises questions about long-term national ownership of ESE content.

Given how few students make it to upper secondary—and how few of those select ESE-relevant subjects—there is an urgent need to rethink how and when these topics are introduced. By focusing ESE at the primary and lower secondary levels, we have the opportunity to make environmental learning inclusive, timely, and culturally grounded.

4. Reflections on Gaps, Possibilities, and the Path Forward

4.1. Disconnect Between Policy and Practice

Tuvalu’s education policy documents speak optimistically about sustainability and environmental awareness. However, upon closer inspection of what is actually delivered in classrooms, the gap becomes hard to ignore. ESE is scattered throughout the curriculum—sometimes hinted at, sometimes overlooked entirely. Biodiversity, climate resilience, and disaster risk reduction might appear in policy language, but they are rarely treated as structured learning outcomes in day-to-day teaching [

2,

29].

Part of the challenge lies in a lack of coherence between different sectors. While the Ministry of Education and the Department of Environment each have relevant mandates, they do not always work in synchronization. This siloed approach means opportunities are missed, and key environmental themes are lost somewhere between strategy and implementation [

31].

4.2. Rethinking the Curriculum for Relevance

Tuvalu’s shift to an outcome-based curriculum was intended to improve clarity and consistency. However, in practice, it sometimes reinforces a rigid, externally shaped model that does not always reflect Tuvalu’s cultural and environmental realities [

32,

33]. Education, in many cases, still emphasizes preparing students for formal employment, even though the majority of people rely on local livelihoods, overseas labor markets, or subsistence-based activities [

33].

This presents a clear opportunity. If the curriculum instead prioritized life skills that are meaningful in local contexts—including environmental stewardship—it could build real resilience. Indigenous knowledge systems, which are rich with environmental wisdom, have been largely left out of formal education. Bringing that knowledge back in—through place-based and community-based learning—would make education more relevant, more empowering, and more engaging [

7,

8].

4.3. Why ESE Must Begin in Primary School

One of the clearest takeaways from this reflection is that ESE needs to start early. Data from recent years show that a significant percentage of students drop out before they reach the final years of secondary school [

25], and even those who make it to Year 13 may not opt for subjects like geography or biology—currently the only pathways through which ESE is taught in any depth [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23].

By contrast, primary school reaches the majority of Tuvaluan students. These are the formative years when curiosity is high and values are still being shaped. Introducing ESE at this stage—when students are open to new ideas and eager to connect with their environment—can lay a foundation for long-term environmental responsibility. It is not just about awareness; it is also about building adaptive capacity and community resilience from the ground up [

28,

34].

4.4. Missing Methods, Missing Moments

Another important challenge is not just what we teach—but how. Less than 2% of instructional time is currently dedicated to environmental themes [

29], and where ESE is present, it tends to follow traditional, lecture-based methods. Experiential, hands-on learning—like growing school gardens, mapping local ecosystems, or participating in community projects—is rare, despite its potential to bring lessons to life through application of environmental awareness and stewardship [

26,

35].

There is also little space for learning that fosters self-awareness, cultural identity, or social action—core elements of environmental stewardship. Without these, students may struggle to connect what they learn with the realities of their lives and communities. The absence of such methods limits both engagement and deeper understanding.

Future research and education reforms could look at integrating approaches like participatory action research, place-based learning, and storytelling. These methods would not only make learning more effective but also help students see themselves as capable of shaping change in their communities [

36,

37].

4.5. Strengthening Engagement Through Cultural and Social Relevance

Improving ESE is also about listening to students, communities, and culture. Many young people in Tuvalu grow up surrounded by traditional ecological knowledge passed down through family and community life. However, formal education often ignores these insights [

7]. That disconnect can leave students feeling detached from school content—and, by extension, from school itself.

Economic pressures and limited educational pathways add further obstacles. When students do not see a link between school and future opportunities, motivation wanes. ESE could help bridge this gap, especially if it is tied to career paths in environmental work, sustainability, or local governance. Mentorship programs, scholarships, and community involvement could offer not just motivation but meaningful purpose [

38].

5. Concluding Reflections: A Call for Early, Culturally Rooted Environmental Learning

Tuvalu’s journey toward a more climate-resilient future must begin in its classrooms. This commentary has reflected on the often overlooked disconnect between policy commitments and what is actually taught in schools when it comes to Environmental Stewardship Education (ESE). What emerges clearly from this reflection is the urgency of starting earlier, teaching differently, and rooting education more deeply in the lived experiences and values of Tuvaluan communities [

2,

3].

We must act early, teach differently, and center education in the lived realities of our communities. The opportunity to shape how students connect with their environment, culture, and future begins now, not at the end of their schooling journey, but at the beginning.

Introducing ESE at the primary level is not just a recommendation—it is a necessity. Most Tuvaluan children do not make it to upper secondary school, where subjects like geography and biology (the only formal avenues for ESE) are taught [

19,

20,

21,

24,

25]. By the time students are old enough to choose these electives, many have already left the system. We are missing the moment when their curiosity is high and their values are still forming [

28,

34].

However, it is not only about when or what we teach. It is about how. Participatory, community-based, and place-based learning approaches offer a real opportunity to connect formal education with local wisdom, daily life, and the climate realities that Tuvaluans face [

7,

39]. These are not just pedagogical preferences—they are strategies for building resilient, environmentally aware citizens.

There is also hope. National frameworks like the Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework (TNCPF) provide a strong starting point to being able to think more innovatively about embedding ESE into curricula. Regional momentum is growing, and there is increasing global recognition of the role education plays in addressing environmental challenges, especially in Small Island Developing States (SIDS) [

40].

Future research and policy efforts should explore how these changes can be made sustainable and scalable, not only in Tuvalu, but across the Pacific and other climate-vulnerable nations. What we learn here could help shape a more just, locally grounded approach to sustainability education worldwide.

The foundation for environmental resilience is built in classrooms—but only if we start early, teach wisely, and honor the wisdom already present in our communities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17094119/s1, Table S1: Environmental stewardship and related concepts in the Years 11–13 Geography syllabus; Table S2: Environmental stewardship and related concepts in Years 11–13 biology syllabus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.T., S.L.H. and A.P.K.; Methodology, S.S.T.; Formal analysis, S.S.T.; Investigation, S.S.T.; Data curation, S.S.T.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.S.T., S.L.H. and A.P.K.; Writing—review and editing, S.S.T., S.L.H., T.G.M., M.H. and A.P.K.; Visualization, S.S.T.; Supervision, A.P.K., S.L.H., T.G.M. and M.H.; Project administration, S.S.T. and A.P.K.; Funding acquisition, S.S.T. and S.L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received external funding from the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission. The funding number to access this fund at the University of Lincoln is 0006192.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of the University of Lincoln, UK: LEAS reference 2021_6409.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by the Commonwealth Scholarships Commission, which has been instrumental in facilitating this research. Additionally, we extend our gratitude to those who have provided administrative and technical support throughout this project. Special thanks to the Tuvalu Education Department, which contributed materials and resources for this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Education Department. Education Statistical Report 2012; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2012. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/publication (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2019. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/publication (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Tinilau, S.S.; Hemstock, S.L.; Mercer, T.G.; Hannaford, M.; Kythreotis, A.P. Environmental Stewardship Education in Tuvalu, Part 1: The Role of Policy Alignment. Sustainability 2025, 17, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havea, P.H.; Tamani, A.; Takinana, A.; De Ramon N’ Yeurt, A.; Hemstock, S.L.; Coombes, H.J.D. Addressing Climate Change at a Much Younger Age Than Just at the Decision-Making Level: Perceptions from Primary School Teachers in Fiji. In Climate Change and the Role of Education; Filho, W.L., Hemstock, S.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, W.; Muttarak, R.; Striessnig, E. Universal education is key to enhanced climate adaptation. Science 2014, 346, 1061–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabawani, B.; Hanika, I.M.; Pradhanawati, A.; Budiatmo, A. Primary schools eco-friendly education in the frame of education for sustainable development. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2017, 12, 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mansoori, F.; Hamdan, A. Integrating Indigenous Knowledge Systems into Environmental Education for Biodiversity Conservation: A Study of Sociocultural Perspectives and Ecological Outcomes. AI IoT Fourth Ind. Revolut. Rev. 2023, 13, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Tuvalu National Curriculum Policy Framework; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2013. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/publication (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Basic Science Syllabus Year 6; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Basic Science Syllabus Year 7; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Basic Science Syllabus Year 8; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Basic Science Syllabus Year 9; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Basic Science Syllabus Year 10; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Social Science Syllabus Year 6; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Social Science Syllabus Year 7; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Social Science Syllabus Year 8; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Social Science Syllabus Year 9; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Social Science Syllabus Year 10; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Biology Syllabus Year 11; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Geography Syllabus Year 11; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports). Geography Syllabus Year 12; Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017.

- EQAP. South Pacific Form Seven Certificate [SPFSC]: Biology Syllabus, 5th ed.; Pacific Community (SPC): Suva, Fiji, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- EQAP. South Pacific Form Seven Certificate [SPFSC]: Geography Syllabus, 5th ed.; Pacific Community (SPC): Suva, Fiji, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Tuvalu (MEYS Tuvalu and EQAP). Biology Syllabus and Prescription Year 12; MEYS Tuvalu and EQAP: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2022.

- Tane, S. Tuvalu School Enrolment in Each Level [email]; Education Department, Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, Funafuti, Tuvalu; Sent to Tinilau, S. 2 February 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J. Introducing a fifth pedagogy: Experience-based strategies for facilitating learning in natural environments. Envioron. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, Z.T. Impact of Whole-School Education for Sustainability on Upper-Primary Students and Their Families. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 2013. Available online: https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/publications/impact-of-whole-school-education-for-sustainability-on-upper-prim (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Taylor, N.; Quinn, F.; Eames, C. (Eds.) Why Do We Need to Teach Education for Sustainability at the Primary Level? In Educating for Sustainability in Primary Schools: Teaching for the Future; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinilau, S.S. An Examination of Formal, Non-Formal, and Informal Environmental Stewardship Education in Tuvalu. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Geography, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Tuvalu (Ministry of Education Youth and Sports). Tuvalu Education Sector Situational Analysis; Ministry of Education Youth and Sports: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/publication (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Government of Tuvalu. 2016 & 2017 Education Statistical Report; Government of Tuvalu: Funafuti, Tuvalu, 2017. Available online: https://meys.gov.tv/statistics (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Yu, F.-L.T. Outcomes-based education: A subjectivist critique. Int. J. Educ. Reform 2016, 25, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Craney, A. Seeking a Panacea: Attempts to Address the Failings of Fiji and Solomon Islands Formal Education in Preparing Young People for Livelihood Opportunities. Contemp. Pac. 2021, 33, 338–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.B.; Buchanan, T.K. Environmental Stewardship in Early Childhood. Child. Educ. 2011, 87, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, K.M.; Ontl, T.A.; Handler, S.D.; Janowiak, M.K.; Brandt, L.A.; Butler-Leopold, P.R.; Shannon, P.D.; Peterson, C.L.; Swanston, C.W. Beyond Planning Tools: Experiential Learning in Climate Adaptation Planning and Practices. Climate 2021, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras-Velazquez, A.; Fronza, V. Sustainability in formal education: Ways to integrate it now. IUL Res. 2020, 1, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbokazi, M.S.; Mkhasibe, R.G.; Uleanya, C. Measuring the Effectiveness of Environmental Education Programmes in Promoting Sustainable Living in Secondary Schools. Tech. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 23, 164–176. [Google Scholar]

- Blimpo, M.P.; Gajigo, O.; Pugatch, T. Financial constraints and girls’ secondary education: Evidence from school fee elimination in the Gambia. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2019, 33, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; DuBois, B. Climate adaptation education: Embracing reality or abandoning environmental values. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.; Hemstock, S. Resilience in Formal School Education in Vanuatu: A Mismatch with National, Regional and International Policies. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 15, 206–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).