Abstract

Systematically synthesizing existing knowledge on ecological resettlements (ERs) is crucial for shaping future research and conservation strategies. We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) using the Web of Science and Scopus databases, analyzing 63 research articles in the review domain of ER. Most reviewed articles emphasize people’s welfare in ERs but adopt traditional review approaches, hindering the identification of specific research gaps. This review identifies and focuses on four cross-cutting themes: anthropocentric notions and social equity, parks–people relationships, political ecology and biodiversity conservation, and connecting nature with people for harmonious coexistence. Further, the review highlights key themes in ER and conservation, emphasizing social equity, political ecology, and human–nature relationships. It underscores the need for social justice, the recognition of displaced communities’ rights, and the promotion of participatory decision making. Conservation efforts should prioritize minimizing displacement and respecting local rights, with a focus on co-management models. Case studies, particularly from India and African countries, reveal the impacts of conservation-induced displacement on marginalized communities and ecosystems. Further, we identified 45 key areas across 15 thematic dimensions for future review and research gaps, which will inform decision making in the discipline. We call for long-term assessments of resettlement to address ecological and social consequences, bridging the gap between social scientists and biologists for balancing conservation and human welfare. Finally, we discuss our findings and propose future research directions to inform conservation policies for the harmonious coexistence of humans and non-human beings on a shared planet.

1. Introduction

Humans and their natural environment share an intricate relationship. Due to the increasing human pressure on natural systems, modern global biodiversity efforts began in the second half of the 19th century, with strict protection mechanisms by the declaration of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 in the United States [1] to safeguard the wilderness. This conservation initiative began by excluding humans from the area and evacuating those who already lived there. Since then, this approach has been widely adopted worldwide, and the trajectory of protected areas (PAs) has led to biodiversity protection [2,3,4]. However, this strategy has also displaced human settlements that had evolved in harmony with nature, particularly in and around wildlife habitats, biodiversity hotspots, or wilderness areas. The number of recorded PAs worldwide has surpassed 286,200 (both terrestrial and marine) [5]. These established PAs were largely adopted with the Yellowstone principle of displacing human settlements. This approach has spread globally and continues to dominate the conservation sector, with few exceptions in community-stewardship conservation initiatives [6,7]. In addition to conservation-led resettlement (CR) or ecological relocation (ER), scholarly attention has focused on this topic from various empirical and review perspectives. However, a systematic review of such studies is sparse.

A better understanding of ER reviews is crucial for exploring consolidated information that can shape conservation-related policies and practices while also fostering a harmonious environment for coexistence between humans and non-human beings. This coexistence, in a safe environment, ensures the path toward achieving local-level livelihoods, ecosystem integrity, and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [8,9], as well as contributing to pathways toward the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) targets [10,11] and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) objectives [12]. These goals encompass socio-economic, ecological, and environmental aspects or their combinations [8,12,13,14], all of which are relevant to ER. A global synthesis of ER would provide an opportunity to make informed decisions at local to global scales, promoting harmonious coexistence and welfare for both people and wildlife (including ecosystems). One of the most effective ways to bridge this gap is to systematically profile the global review literature on the topic.

In acknowledgment of the multi-faceted implications of ER, research on this subject has been growing worldwide. For example, some scholars focus on the socio-economic aspects of resettled societies [2,3,15,16], ecological aspects of conservation [17], land cover changes in resettled and evacuated sites [18], and both positive outcomes and negative impacts on people and ecosystems [19,20,21]. A few scholars have reported on changes in water regimes [22], the loss of ethnobotanical knowledge [23], or the effects on plants, soil [20], or species conservation [17] due to ER. However, this research is piecemeal, theme-based, and site-specific, lacking a single synthesis that provides a global perspective on the geographical sites and communities impacted by ER.

Few review syntheses on ER have focused on various themes and scales. For example, studies address social equity in conservation [24], managed retreat [25], relocation typology [26], protection and impoverishment [27], natural resource management, Indigenous communities [28], and biodiversity offsetting impacts [29]. Some provide global overviews [30,31] or focus on park–people relationships [32,33], regional scales [34,35,36], country-specific studies [37,38,39], or in landscapes [40] and the landscape level [41,42]. These studies often focus on specific conservation or social aspects [43,44,45] or certain communities [46] and adopt conventional review methods [27,30,31]. Some studies offer limited accounts of conservation-led resettlements [33,47], but they are patchy and fail to explore research gaps [47]. Conventional reviews also struggle to quantify themes such as geographical distribution, research focus, and methodology, making it hard to identify review gaps. In contrast, a systematic literature review (SLR) reduces bias [48] and ensures replicability and validity [49,50,51]. Therefore, an SLR of ER review literature is vital for identifying research gaps and providing robust, global evidence to inform decision making.

In this review, we aim to provide a global perspective on the review of reviews related to conservation-led resettlement (CR) or ecological relocations (ERs). Specifically, the study focuses on (1) synthesizing the existing literature on reviews conducted so far and (2) identifying the thematic focus of the selected review articles while highlighting gaps in both reviews and empirical studies within the field. For clarity, we define ER or CR as the physical displacement of humans (or settlements) from their original area of residence to other areas for the primary purpose of biological conservation, as defined by Yarina and Wescoat (2023), unless otherwise stated. Additionally, we interchangeably use terms such as conservation, displacement, resettlement, relocation, dispossession, realignment, retreat, evacuation, and eviction, or combinations thereof, to convey the same or equivalent meanings within the framework of global typological risk-based relocation [26].

2. Method

2.1. Literature Searching and Screening Strategy

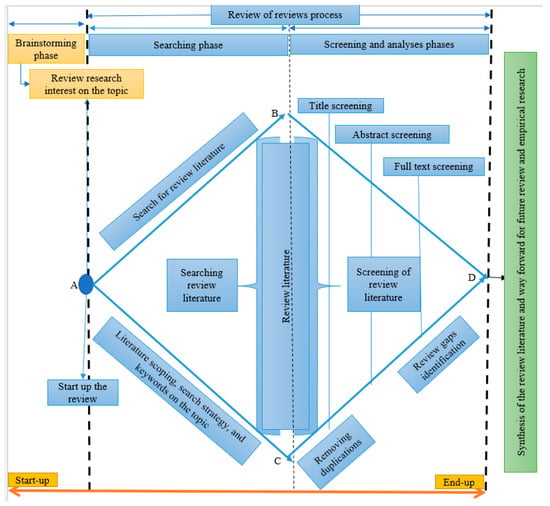

This review employed a standard procedure for systematic literature searching and screening strategies [52,53]. SLRs aim to provide deep, narrative insights into research findings, methods, and knowledge gaps. In contrast, visualization-based reviews focus on structural relationships such as keyword co-occurrence, author networks, or citation clusters, offering a big-picture overview of the field where our focus in this paper is not this line. An SLR approach ensures comprehensive inclusion of all relevant literature on the topic, while also refining the search strategies and quantifying the background literature review process (see details in Figure 1). This framework provides a review protocol that can be applied to this study and future review studies.

Figure 1.

The research design for systematic literature review of reviews (systematic review of reviewed literature). A is the startup of a formal review process to search for review literature, BC spans the piles of literature in the search across the databases, and D is the end of the formal review process.

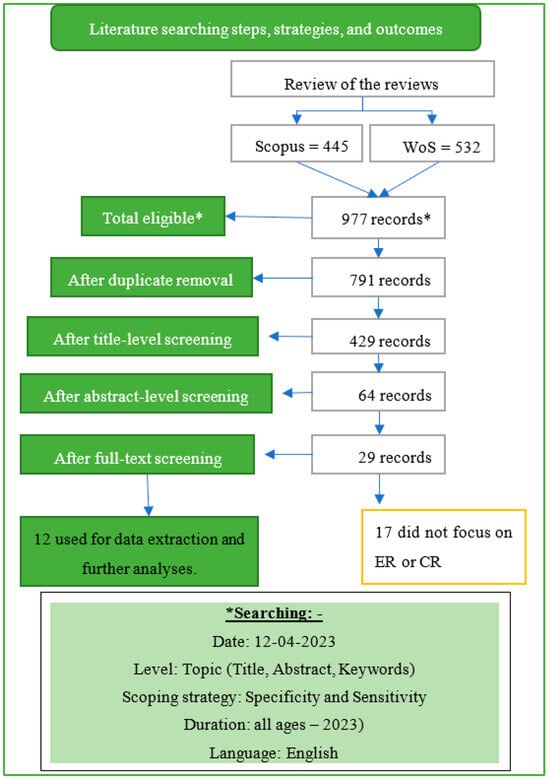

A systematic procedure was followed for the literature search. Firstly, brainstorming was carried out to explore the keywords, their synonyms, and equivalent alternatives. Secondly, we used these words in an iterative process to map the reviewed literature on the topic. In this stage, we finalized the search keywords, taking into consideration the synonymous words referring to more than 20 reviews on the subject, e.g., [26,41,54,55], and considering the sensitivity and specificity of the systematic literature review [48]. The final keywords used for searching strings were “Conservation” OR “Ecological” AND “Displacement” OR “Resettlement” OR “Relocation” OR “Dispossession” OR “Realignment” OR “Retreat”, after validating with experts (n = 3). Thirdly, these search strings were used to explore peer-reviewed review articles from two prominent science databases, namely Web of Science and Scopus, from all years to 2023 (till 12 April). Fourthly, the obtained review articles were screened via title, abstract, and full text to identify the research gaps for our review study (Figure 1). Additionally, subject-specific searches on grey literature and thematic libraries such as libraries of human rights, a database of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and webpages of the Protected Areas’ Congress were also performed. Only those articles published in English were included in the screening process (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The search strategies and quantitative outcomes of the literature during the review process for this study.

2.2. Literature Screening and Shorting

All the reviewed articles identified by the search strings underwent a three-stage screening process before data extraction. Using specific inclusion criteria (Figure 2), the screening was conducted at the title, abstract, and full-text levels for the 977 review articles extracted from the mentioned databases. A micro-level screening and data extraction process ultimately narrowed this down to 12 articles that directly synthesized empirical studies on ecological or conservation-led resettlements.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analyses

The three levels of rigorous screening culminated in the final selection of 12 reviewed articles for synthesis and discussion. After conducting multi-phase screening, we identified only 12 reviewed articles that qualified for synthesis and discussion. A qualitative data analysis approach was used to synthesize the findings of past review research, particularly in tabular format.

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of the Review’s Literature

We summarized the existing body of knowledge from the review literature on related topics (Table 1). While a comprehensive systematic review covering all research in this field eluded our search, we consolidated the existing syntheses conducted to date. The thematic elements within these review articles were carefully curated through a thorough examination of the texts, capturing the broader perspectives and opinions expressed by the authors. Additionally, the highlights summarize the key emphases outlined in the review articles.

Table 1.

Summary of the existing review literature on topic-related subjects.

3.2. Review and Research Gaps on the Topic

Research on conservation projects highlights the socio-economic inequalities created by displacement, particularly in terms of local communities’ access to resources and decision-making power. There is a gap in understanding how displacement impacts social structures and the effectiveness of compensation schemes and property rights in mitigating both social and ecological consequences of forced resettlements. Further studies are needed to explore the long-term effects of conservation-induced displacement on communities’ well-being and their role in conservation decision making (Table 2).

Table 2.

Key review and research gaps on ecological resettlements and conservation-led resettlement.

This review identifies key themes in ecological resettlement (ER) and conservation-led displacement (CLD), highlighting gaps in existing literature. It emphasizes the anthropocentric notion and social equity, advocating for the integration of social justice (distribution, recognition, participation) and environmental justice policies to address the displacement of communities. It discusses parks–people relationships, emphasizing the conflict between protected areas (PAs) and local communities, and the need for anthropological and political economic considerations in conservation. The review also explores political ecology, i.e., different stakeholders in biodiversity conservation, including social actors with unequal political power, involving competition for access to and control of natural resources, shaping policy prescriptions [56,60,61], arguing for a balance between human welfare and biodiversity conservation without displacement. It underscores the importance of respecting local rights, informed consent, and minimizing displacement to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). Additionally, the review connects nature with people, calling for further study on eviction from ecosystems beyond PAs, and highlights the need for comprehensive case studies, particularly in countries like India. The review stresses the importance of assessing the ecological and social consequences of CR and ER, bridging the gap between social scientists and biologists to achieve integrated conservation and social welfare.

4. Discussion

This review synthesized the literature on ecological resettlement (ER) and conservation-led displacement, identifying key gaps and proposing a systematic approach to address them. While many studies emphasize human-centered aspects, such as livelihoods, cultural integrity, and resource rights, others focus on balancing conservation goals with human welfare. The review highlights the need for comprehensive, long-term research integrating social, ecological, and economic dimensions to ensure ethically and practically sound conservation efforts. It emphasizes empowering local communities, ensuring fair benefit-sharing, and fostering participatory co-management. The review calls for transparent, voluntary displacement processes and a thorough evaluation of ecological costs and benefits. This approach allows for quantifying background information and encourages synthesizing existing review literature to formulate research questions. Current systematic literature review (SLR) approaches often overlook these critical aspects [48,62,63,64], making the review within an SLR framework essential to addressing knowledge gaps and affirming the uniqueness of current knowledge.

4.1. Discourses of Past Reviews Synthesis on Conservation-Led Displacement

In synthesizing the reviewed literature, there is a distinct divide in how ecological resettlement is perceived. Most studies emphasize the anthropocentric perspective, focusing on the livelihoods, resource rights, and cultural integrity of communities [35,54,65]. A minority prioritizes nature conservation, striving to strike a balance between conservation and livelihoods [30,31]. However, there is a consensus across these syntheses on the importance of harmonizing wildlife and human coexistence. These studies advocate for environmental policy reforms that favor participatory and co-management models [59], which respects human rights and welfare, aiming to benefit local and indigenous communities [30,31,43,45,66]. Others argue that coexistence is not only essential for people but also critical for optimizing natural resources, contributing to overall well-being, and the achievement of sustainable socio-ecological landscapes [45,46,67]. This body of work underscores the need for more balanced ground-level research that encompasses all dimensions—social (economic, health, security, cultural, political, institutional), ecological (non-living), and ecosystem aspects—of ER.

Additionally, some scholars advocate for displacement that is ethically justified and done with local consent, believing it can effectively conserve nature while fulfilling the needs of displaced communities [39,54,58]. Conversely, others argue that conservation-led resettlements are often exacerbated by broader mega-development projects, leading to economic redistribution and human rights concerns [30,31]. However, there is a perspective emphasizing that successful conservation hinges on empowering local communities, providing cultural benefits, and ensuring support from nature. Conservation initiatives should aim at positive socio-economic enhancement, establish participatory co-management models, and ensure fair benefit-sharing mechanisms [43,68]. Some scholars believe that conservation and human welfare can coexist without displacing either people or nature. They advocate for wise political decisions through transparent dialogues between social scientists and naturalists, favoring voluntary processes over coercion [30,32,37]. This approach requires comprehensive, long-term research across all dimensions of ecological resettlement to ensure a justifiable process, particularly considering the ecological costs and benefits [35]. Further research on all aspects of ER, covering its phases, promoting participatory decision-making, and ensuring equitable benefit-sharing from conservation outcomes, could enhance stewardship and ownership among all stakeholders, fostering harmonious coexistence on our shared planet.

Furthermore, some scholars highlight that due care and justified displacement, aligned with the aspirations of the local people, can be ethical and effective in achieving nature conservation while fulfilling the aspirations of displaced communities [39,54,58]. Other researchers argue that the issue of conservation-led resettlements is aggravated because this type of displacement is often driven by large-scale development projects and associated economic redistribution, which is further complicated by human rights concerns [30,31]. However, scholars believe that conservation success depends on empowering local communities, providing cultural benefits, and ensuring support from nature at the local level. Conservation initiatives should aim to promote positive socio-economic enhancement, establish co-management participatory models, capacitate local people, and ensure justice in the benefits-sharing mechanism arising from conservation [43]. Nature conservation and human welfare can coexist without displacing either people or nature, through wise political decisions, dialogue, and discussions between social scientists and naturalists, with transparent and voluntary processes when displacement is unavoidable [30,32,37]. This requires long-term research—pre-, during, and post-relocation—on all dimensions of ER for a justifiable process [37]. The critical issue of ecological costs and benefits of resettlement cannot be fully justified without long-term research evidence [35]. Therefore, more research covering all phases of ER, promoting participatory decision-making, and ensuring equitable benefits sharing from conservation outcomes could enhance local stewardship and foster harmonious coexistence among all stakeholders, including governments, for a shared planet.

The existing body of review literature lacks synthesis through a systematically assessed approach to ER-related literature. However, a few studies on the topic have been conducted using traditional methods. For example, West et al. (2006) [33] examined the relationship between parks and people, focusing on the social dimension of communities living in and around protected areas. Their study primarily explores the social, material, and symbolic effects of people’s livelihoods concerning protected areas [33]. Most studies focus on specific countries, regions, or protected areas. This is the first attempt to review ER-related literature using a systematic review and double diamond approach in the existing body of scholarship. West et al. (2006) [33] argue that the anthropological and political-economic impacts of creating protected areas should be considered, and they suggest implementing protection in areas where people have not historically resided.

Geisler (2003) [27] appears to be one of the anthropocentric philosophers, and this notion is reflected in his study. For example, the protected area system hinders development projects and creates conservation refugees through dispossession and displacement, which is justified by conservation. This new form of eviction can be addressed through environmental justice policy advocacy, supporting the conservation of refugees within a political-ecological decision-making framework for the creation or expansion of protected areas. Ultimately, strict protection may be a viable option in certain conditions; however, many synergetic strategies can harmonize and optimize both conservation and development outcomes for social and ecological well-being [25,43]. The success of conservation depends on empowerment, cultural benefits, and local support from surrounding residents. Therefore, conservation initiatives should focus on promoting positive socio-economic enhancement, establishing co-management participatory models, empowering local people, and ensuring justice in benefit-sharing mechanisms arising from conservation for the local community [43].

Adams and Hutton (2007) [32] summarized the political ecology of biodiversity conservation in three dimensions: Indigenous people’s rights, the intertwined relationship between biodiversity conservation and its impact on human welfare, and arguments against the conventional approach of protected area management through the displacement of human settlements [32]. For this different interest groups and stakeholders involved in biodiversity conservation, and analyze the policy prescriptions [56,60]. They argue that nature conservation and human welfare can coexist without displacing people or nature. Still, they can thrive together through wise political decisions made via dialogue between science-trained social scientists and naturalists. Furthermore, they propose that human projects in non-human natural landscapes could offer a promising way to harmonize humans and nature, moving beyond the traditional mindset of human-excluded protection [32]. However, this study is largely focused on human-centric perspectives, as it does not address the fact that humans have intervened in nature within protected areas for decades or even centuries.

Brockington and Igoe (2006) [31] is one of the most comprehensive studies on evictions for conservation purposes. This study synthesized over 250 reports, but it focused only on evictions from protected areas and did not address evictions from other ecosystems where conservation is the primary objective [31]. The literature they reviewed was fragmented and inadequate, clearly indicating the need for more systematic study to synthesize the body of knowledge and connect people with nature. Scholars argue that there are likely many more evictions for conservation purposes that have not yet been reported in the literature [31]. Our study provides a complete list of areas and communities reported in empirical studies across the globe, offering concrete evidence and shaping the path for identifying research gaps related to evictions for conservation, including the impacts on national parks, species concerns, and, of course, the affected communities.

O’Donnell (2022) [25] is one of the latest reviews on managed and planned retreats, similar to our study, though not specifically focusing on conservation-led resettlements. This study primarily explores spatial scholarship, property rights, and compensation schemes in relation to climate change-driven retreats and their aftermath. It advocates for incorporating political economy scholarship in climate change-driven retreat activities to promote social and environmental justice [69], particularly focusing on marine ecosystems [25]. The study further suggests that broader justice and equity themes are crucial for just policies and actions related to managed retreats. As the literature emphasizes substantive social justice, future research could explore this direction [25].

Similarly, Fernandes (2001) [46] synthesizes the impact of development-induced displacement on sustainable development, with a particular focus on marginalized women. The study concludes that such displacement leads to the impoverishment and disempowerment of marginalized women, contradicting the goals of sustainable development. It recommends minimizing displacement, ensuring and respecting local rights and livelihoods, and obtaining prior informed consent before initiating development projects. While monetary compensation may partially support livelihoods, it does not restore cultural structures and community systems. Therefore, development projects should involve local people as decision-making and benefit-sharing partners, rather than merely subjects of rehabilitation [46].

4.2. Regional and Country-Specific Reviews

Geisler and De Sousa (2001) [35] provide country-specific cases from Africa and propose environmentally sound land reform as a mitigation strategy for the irreparable losses caused by conservation-led resettlement [35]. A study in Kenya suggests that expanding conservation from an ecosystem to a landscape scale can benefit both pastoralist communities and wildlife conservation. This approach involves reinforcing pastoral practices in open spaces, enabling movement and social interaction through institutional arrangements to manage large-scale pasturelands. It can be achieved by promoting eco-tourism, ensuring equitable benefit-sharing, and creating local employment opportunities through nature-based tourism [67]. These strategies enhance the well-being of communities outside protected areas while conserving wildlife within parks and pastures. In Namibia, Vehrs and Zickel (2023) [55] examined the historical context and consequences of conservation-induced displacement in the Zambezi Region, particularly in the Lyanshulu area. They highlight how the establishment of conservation areas, such as Mudumu National Park, led to the displacement of local communities from their ancestral lands. Affected families have increasingly protested and legally challenged their exclusion from these lands, now designated as protected areas. The authors argue that for conservation efforts to succeed, both past and present environmental injustices must be comprehensively addressed.

Country-focused syntheses are relatively abundant in the literature, particularly in India. Fanari (2019) [57] highlights how the violent relocation of human settlements from protected forest areas leads to conflicts between parks and people, jeopardizes the tenure rights of forest dwellers, and contradicts India’s Forest Rights Act. The study criticizes the displacement of anthropogenic landscapes, arguing that removing human activities, rights, and culture fosters violence and social inequality while simultaneously reinforcing government dominance over natural resources through neoliberal policies and power structures [57]. Similarly, Lasgorceix and Kothari (2009) [37] examined the economic and cultural impacts of displacement and relocation from protected areas in India. They question the ecological justification for resettlement, arguing that the assumption of reduced pressure on wildlife habitats is unsupported due to gaps in research on both evacuated and resettled sites. The study underscores the need for comprehensive, long-term assessments before, during, and after relocation to fully understand the socio-economic and environmental impacts of ecological resettlement [37].

Rangarajan and Shahabuddin (2006) [58] synthesized cases of displacement and relocation in India, noting a disciplinary divide in the literature: social scientists focus on the social dimensions of resettled communities, while biologists and natural scientists examine human impacts on ecosystems and wildlife. They emphasize the need to sensitize biologists and forest managers to the socio-economic and cultural significance of resident communities while encouraging social scientists to recognize the importance of species and ecosystem conservation. Additionally, they argue that ethical and well-justified displacement, aligned with local aspirations, can be both effective and morally sound in achieving conservation goals. They advocate for a transparent, voluntary, and discursive approach to coercion [39,54,58]. Agrawal and Redford (2009) [30] contend that conservation-led resettlements are further complicated by their intersection with large-scale development projects, economic redistribution, and human rights concerns [30]. They highlight the ethical dilemma of balancing conservation objectives with human rights, warning that forced displacement may not only violate human rights but also contribute to species extinction. To ensure long-term conservation success, they recommend that conservation organizations adopt ethically sound approaches to address conservation-induced displacement [30,31].

Overall, these reviews offer limited comprehension of existing studies compared to global literature and often do not focus primarily on ER or CR. A systematic review of global ER literature is essential to identify research gaps, analyze trends, and provide robust evidence for informed decision making. Our study partially fills this gap and is a pioneering effort on ER from a comprehensive perspective. However, significant scope remains for further reviews, including knowledge mapping, applying diverse theoretical frameworks, climate and livelihood perspectives [70,71], and exploring various dimensions of ER research from local to global scales.

4.3. Limitation, Scope, and Future Pathways

This paper provides a novel summary of peer-reviewed global articles on conservation-led resettlements. It examined the current state of reviewed knowledge and identifies research gaps for both review and empirical studies [53]. However, it does not cover all ER efforts, focusing specifically on empirical studies published in peer-reviewed, science-based journals indexed in Web of Science and Scopus. We acknowledge that our review is limited to English-language articles from peer-reviewed journals. Scholarly works in books, book chapters, non-English publications, grey literature, reports, policy documents, discussion papers, and unpublished literature are not included, leaving room for future research in these areas. Additionally, the scope of this review extends beyond the thematic analysis of Pandey et al. (2024) [47] on conservation-led displacement and ecological resettlements [47], suggesting further areas for review and empirical research in the field.

Nevertheless, this study enhances the understanding of ER in both practical and theoretical contexts. It contributes to the social-ecological perspective [72], political ecology, and environmental governance through decision making and dispossession [61,73]. It also applies to biodiversity conservation and sustainable management [10,14] and provides insights into social justice, human rights, and equity, particularly for marginalized and vulnerable populations [74,75,76]. Additionally, it broadens ecological justice discourse [76,77,78,79] and considers ethical implications for both human and non-human entities, aligning with planetary justice [78,80,81]. Furthermore, the study offers insights into the social, ecological, and environmental dimensions of ER, supporting policy formulation and implementation. These interconnected aspects contribute to local and global goals, including poverty reduction, SDG achievement, CBD targets, and climate action under the UNFCCC. Ultimately, this research provides a foundation for systematizing ER guidelines and improving discipline-wide frameworks [30,47].

The findings from this review suggest that existing ecological resettlement literature often lacks synthesis and fails to address the full scope of the issue. While past studies have focused on specific regions or aspects of resettlement, there is a clear need for a more systematic global review. Our research not only identifies significant gaps but also contributes to the broader discourse on social justice, human rights, and environmental governance. By using a double-stage review process, this study offers valuable insights into how conservation and human welfare can coexist and calls for more research to develop equitable, sustainable models for ecological resettlement. This research sets a foundation for future studies and policy development, emphasizing the importance of integrating both social and ecological factors in conservation planning.

5. Conclusions and Ways Forward

This study presents the first global review of systematic literature reviews on ecological resettlements (ERs) and conservation-led relocation. Analyzing over 900 journal articles from Web of Science and Scopus, we screened 63 reviews using a novel “review of reviews” methodology. While interest in ER is growing, our findings highlight a persistent gap in informed decision making and responsible execution, revealing weak governance in conservation science. Without policy revisions that better integrate human–nature connections, national and international conservation goals may remain unfulfilled. Government-led ER initiatives dominate, yet nearly all reviews report forced evictions, livelihood disruptions, access restrictions, and human rights violations, disproportionately impacting the poorest and Indigenous communities. These communities, deeply intertwined with natural systems, often face relocation without consent, fair compensation, or consideration for their cultural ties, voice, and choice. This imbalance threatens both societal and ecological well-being. Despite global treaties advocating for Indigenous rights, the reality on the ground starkly contradicts these commitments. ER programs fail to uphold even basic rights, necessitating global guidelines and oversight institutions to safeguard displaced communities’ fundamental needs, human rights, and land-based traditions. To prevent repeating past injustices, ER policies must align with sustainable development principles and good governance—not just in theory but in practice—to ensure the coexistence of human and non-human life on our shared planet.

Our analysis highlights key insights for future research and policy directions on ER: (1) Comprehensive exploration of ER’s political, social, economic, cultural, ecological, and spatial dimensions remains limited. (2) Few studies synthesize existing knowledge, and only one employed a systematic review, underscoring the need for transdisciplinary thematic analysis and empirical research. (3) Limited cross-sectoral authorship suggests opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration to achieve balanced social and ecological outcomes. (4) Understanding local political ecology—viz., the differing interests of social actors with asymmetrical political power competing for access to and control of natural resources, along with government interests, commitments, and international pressures, as well as the roles of stakeholders on the ground—is essential for effective ER policies. (5) Applying diverse frameworks to assess ER research can provide multiple perspectives to guide decision making. (6) Future research should adopt participatory approaches to enhance public accountability, ownership, and stewardship—elements often missing in past studies. This review underscores the importance of integrating human and ecological dimensions, reinforcing the need for just conservation policies that balance both aspects for sustainable outcomes.

Author Contributions

H.P.P.: Conception, Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, and Writing the original draft; T.N.M.: Review and editing, Supervision, and Discussion; A.A.: Review and editing, Supervision, and English proofing; H.Z.: Review and editing, Supervision, and English proofing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific funding.

Data Availability Statement

No specific data was used; this was a review of review articles.

Acknowledgments

The first author sincerely thanks the Australian Government and the University of Southern Queensland for the Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship and International Fees Research Scholarship that made this study possible. The first author also acknowledges the Government of Nepal for granting study leave for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no financial or other conflicts of interest among the authors or supporting organizations related to this study, the data used, or any other aspects of this research.

References

- Haines, A.L. Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment; U.S. National Park Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Maclean, J.; Strade, S. Conservation, Relocation, and the Paradigms of Park and People Management—A Case Study of Padampur Villages and the Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.; Paul, S.; Sarma, V. Reversal of Fortune? The Long-Term Effect of Conservation-Led Displacement in Nepal. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2016, 44, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, E.G. Conserving Dispossession? A Genealogical Account of the Colonial Roots of Western Conservation. Ethics Policy Environ. 2021, 24, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP-WCMC and IUCN Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database on Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM) 2023. Available online: https://www.protectedplanet.net/en/thematic-areas/oecms?tab=OECMs, (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Maraseni, T.N.; Neupane, P.R.; Lopez-Casero, F.; Cadman, T. An Assessment of the Impacts of the REDD+ Pilot Project on Community Forests User Groups (CFUGs) and Their Community Forests in Nepal. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 136, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, H.; Pokhrel, N. Formation Trend Analysis and Gender Inclusion in Community Forests of Nepal. Trees For. People 2021, 5, 100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN The 17 Goals: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Pascual, U.; Balvanera, P.; Díaz, S.; Pataki, G.; Roth, E.; Stenseke, M.; Watson, R.T.; Başak Dessane, E.; Islar, M.; Kelemen, E.; et al. Valuing Nature’s Contributions to People: The IPBES Approach. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBD Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets for 2030 In Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement 2022. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022 (accessed on 2 April 2024).

- Yinuo Press Release: Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets for 2030 In Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement. United Nations Sustainable Development 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2022/12/press-release-nations-adopt-four-goals-23-targets-for-2030-in-landmark-un-biodiversity-agreement/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023—IPCC 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- US EPA, Learn About Environmental Justice. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47920 (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- IPBES Report of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on the Work of Its Fourth Session | System of Environmental Economic Accounting. Available online: https://seea.un.org/content/report-plenary-intergovernmental-science-policy-platform-biodiversity-and-ecosystem-services (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Mahapatra, A.K.; Tewari, D.D.; Baboo, B. Displacement, Deprivation and Development: The Impact of Relocation on Income and Livelihood of Tribes in Similipal Tiger and Biosphere Reserve, India. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuki, K. The Violence of Involuntary Resettlement and Emerging Resistance in Mozambique’s Limpopo National Park: The Role of Physical and Social Infrastructure. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2023, 6, 240–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Kong, D.; Wu, C.; Møller, A.P.; Longcore, T. Predicted Effects of Chinese National Park Policy on Wildlife Habitat Provisioning: Experience from a Plateau Wetland Ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, R.V.; Ogra, M.V.; Badola, R.; Hussain, S.A. Conservation-Induced Resettlement as a Driver of Land Cover Change in India: An Object-Based Trend Analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 69, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Wang, K. Eco-Compensation Effects of the Wetland Recovery in Dongting Lake Area. J. Geogr. Sci. 2010, 20, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Gongbuzeren; Zhuang, M.; Ji, B. Ecological Consequence of Nomad Settlement Policy in the Pasture Area of Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: From Plant and Soil Perspectives. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, K. Authoritarian Environmentalism, Just Transition, and the Tension between Environmental Protection and Social Justice in China’s Forestry Reform. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 131, 102574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Hu, W.; Zhang, B.; Li, G.; Shen, S.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y. Assessing Impacts of the Ecological Retreat Project on Water Conservation in the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katin, N. Exploring the Ecological Dimensions of Displacement in Núcleo Itariru (Serra Do Mar State Park): An Ethnobotanical Study of Peasant/Landscape Relations in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. J. Ethnobiol. 2020, 40, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, R.S.; Law, E.A.; Bennett, N.J.; Ives, C.D.; Thorn, J.P.R.; Wilson, K.A. How Just and Just How? A Systematic Review of Social Equity in Conservation Research. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 053001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, T. Managed Retreat and Planned Retreat: A Systematic Literature Review. Philos. Trans. B 2022, 377, 20210129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarina, L.; Wescoat, J.L. Spectrums of Relocation: A Typological Framework for Understanding Risk-Based Relocation through Space, Time and Power. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 79, 102650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, C. A New Kind of Trouble: Evictions in Eden*. Int. Soc. Sci. J. 2003, 55, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Sudarsan, D.; Santos, C.A.G.; Mishra, S.K.; Kar, D.; Baral, K.; Pattnaik, N. An Overview of Research on Natural Resources and Indigenous Communities: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on Scopus Database (1979–2020). Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupala, A.-K.; Huttunen, S.; Halme, P. Social Impacts of Biodiversity Offsetting: A Review. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 267, 109431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Redford, K. Conservation and Displacement: An Overview. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockington, D.; Igoe, J. Eviction for Conservation: A Global Overview. Conserv. Soc. 2006, 4, 424–470. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Hutton, J. People, Parks and Poverty: Political Ecology and Biodiversity Conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2007, 5, 147–183. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and Peoples: The Social Impact of Protected Areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, B.; Sunderland, T.; Maisels, F.; Oates, J.; Asaha, S.; Balinga, M.; Defo, L.; Dunn, A.; Telfer, P.; Usongo, L.; et al. Are Central Africa’s Protected Areas Displacing Hundreds of Thousands of Rural Poor? Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, C.; De Sousa, R. From Refuge to Refugee: The African Case. Public Adm. Dev. 2001, 21, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, S.; Wilshusen, P.; Brockington, D.; Seidler, R.; Bawa, K. Beyond Exclusion: Alternative Approaches to Biodiversity Conservation in the Developing Tropics. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2010, 2, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasgorceix, A.; Kothari, A. Displacement and Relocation of Protected Areas: A Synthesis and Analysis of Case Studies. Econ. Political Wkly. 2009, 44, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shahabuddin, G.; Bhamidipati, P.L. Conservation-Induced Displacement: Recent Perspectives from India. Environ. Justice 2014, 7, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, B.; Wang, M. Voluntary and Involuntary Resettlement in China: A False Dichotomy? Dev. Pract. 2015, 25, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harihar, A.; Ghosh-Harihar, M.; MacMillan, D.C. Human Resettlement and Tiger Conservation—Socio-Economic Assessment of Pastoralists Reveals a Rare Conservation Opportunity in a Human-Dominated Landscape. Biol. Conserv. 2014, 169, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaminsen, T.A.; Bryceson, I. Conservation, Green/Blue Grabbing and Accumulation by Dispossession in Tanzania. J. Peasant. Stud. 2012, 39, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratford, E. Belonging as a Resource: The Case of Ralphs Bay, Tasmania, and the Local Politics of Place. Environ. Plan. A 2009, 41, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.E.; Evans, K.L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda-Pinto, M.; Kennedy, C.; Collier, M.; Cooper, C.; O’Donnell, M.; Nulty, F.; Castañeda, N.R. Finding Justice in Wild, Novel Ecosystems: A Review through a Multispecies Lens. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 83, 127902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickgraf, C.; Ali, S.H.; Clifford, M.; Djalante, R.; Kniveton, D.; Brown, O.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S. Natural Resources, Human Mobility and Sustainability: A Review and Research Gap Analysis. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 1077–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, W. Development Induced Displacement and Sustainable Development. Soc. Change 2001, 31, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A. Insights into Ecological Resettlements and Conservation-Led Displacements: A Systematic Review. Environ. Manag. 2024, 75, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Bethel, A.; Dicks, L.V.; Koricheva, J.; Macura, B.; Petrokofsky, G.; Pullin, A.S.; Savilaakso, S.; Stewart, G.B. Eight Problems with Literature Reviews and How to Fix Them. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4, 1582–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarborough, M. Moving towards Less Biased Research. BMJ Open Sci. 2021, 5, e100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Ide, T.; Barnett, J.; Detges, A. Sampling Bias in Climate–Conflict Research. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.C.; van Binsbergen, J.; van Weel, C. Systematic Reviews Incorporating Evidence from Nonrandomized Study Designs: Reasons for Caution When Estimating Health Effects. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, S155–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.A. Enhancing Systematic Literature Review Adapting ‘Double Diamond Approach’. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt-Soltau, K.; Brockington, D. Protected Areas and Resettlement: What Scope for Voluntary Relocation? World Dev. 2007, 35, 2182–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehrs, H.-P.; Zickel, M. Can Environmental Injustices Be Addressed in Conservation? Settlement History and Conservation-Induced Displacement in the Case of Lyanshulu in the Zambezi Region, Namibia. Hum. Ecol. 2023, 51, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, I.; Beltran, O.; Paquet, P.A. Political Ecology and Conservation Policies: Some Theoretical Genealogies. J. Political Ecol. 2013, 20, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanari, E. Relocation from Protected Areas as a Violent Process in the Recent History of Biodiversity Conservation in India. Ecol. Econ. Soc.–INSEE J. 2019, 2, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangarajan, M.; Shahabuddin, G. Displacement and Relocation from Protected Areas: Towards a Biological and Historical Synthesis. Conserv. Soc. 2006, 4, 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.; Aryal, K. Unlocking the Tapestry of Conservation: Navigating Ecological Resettlement Policies in Nepal. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K. The Political Ecology of Biodiversity, Conservation and Development in Nepal’s Terai: Confused Meanings, Means and Ends. Ecol. Econ. 1998, 24, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, R.L.; Bailey, S. Third World Political Ecology; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-415-12744-8. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, A.M.; Tsafnat, G.; Gilbert, S.B.; Thayer, K.A.; Shemilt, I.; Thomas, J.; Glasziou, P.; Wolfe, M.S. Still Moving toward Automation of the Systematic Review Process: A Summary of Discussions at the Third Meeting of the International Collaboration for Automation of Systematic Reviews (ICASR). Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (Prisma-p) 2015: Elaboration and Explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanari, E. Struggles for Just Conservation: An Analysis of India’s Biodiversity Conservation Conflicts. J. Political Ecol. 2022, 28, 1051–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Towards Harmonious Conservation Relationships: A Framework for Understanding Protected Area Staff-Local Community Relationships in Developing Countries. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 25, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, D.; Tyrrell, P.; Brehony, P.; Russell, S.; Western, G.; Kamanga, J. Conservation from the Inside-out: Winning Space and a Place for Wildlife in Working Landscapes. People Nat. 2020, 2, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.; Bhusal, S. Decoupling REDD+ Understanding of Local Stakeholders on the Onset of Materializing Carbon Credits from Forests in Nepal. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A. Assessing the Theoretical Scope of Environmental Justice in Contemporary Literature and Developing a Pragmatic Monitoring Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Maraseni, T.N.; Apan, A.; Bhusal, S. Achieving SOC Conservation without Land-Use Changes between Agriculture and Forests. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, H.P.; Aryal, S.; Poudyal, B.H.; Bhusal, S.; Maraseni, T.N. Navigating Climate Change: Impacts on Indigenous Practices Concerning Agrifood Systems in Nepal’s Socio-Ecological Landscape. Sustain. Horiz. 2025, 14, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Do Institutions for Collective Action Evolve? J. Bioecon. 2014, 16, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svarstad, H.; Benjaminsen, T.A.; Overå, R. Power Theories in Political Ecology. J. Political Ecol. 2018, 25, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Social Justice; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1979; ISBN 978-0-19-159079-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mohai, P.; Pellow, D.; Roberts, J. Environmental Justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. Theorising Environmental Justice: The Expanding Sphere of a Discourse. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, B.H. Ecological Justice and Justice as Impartiality. Environ. Politics 2000, 9, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, B. A Theory of Ecological Justice; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1-134-38602-4. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, A. Sentientist Politics: A Theory of Global Inter-Species Justice; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-0-19-250702-0. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.; McGuire, S.; Sullivan, S. Global Environmental Justice and Biodiversity Conservation. Geogr. J. 2013, 179, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashwan, P.; Biermann, F.; Gupta, A.; Okereke, C. Planetary Justice: Prioritizing the Poor in Earth System Governance. Earth Syst. Gov. 2020, 6, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).