Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

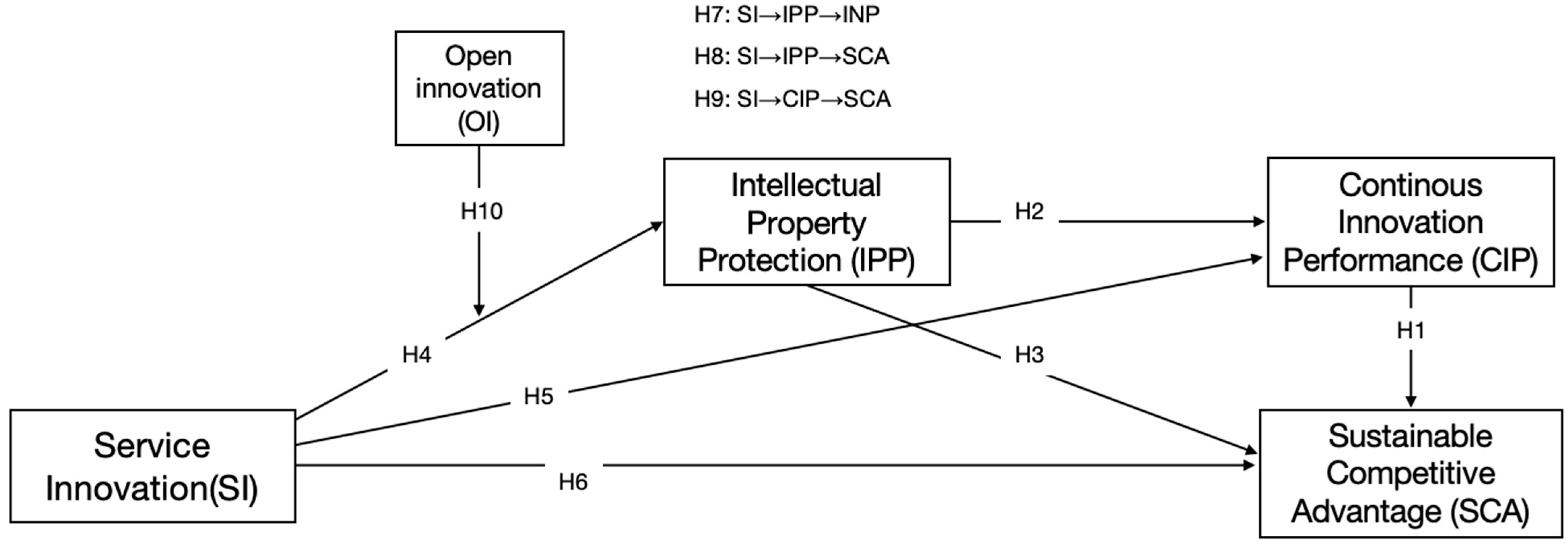

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Resource-Based View (RBV)

2.2. Firm Continuous Innovation Performance (CIP) and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA)

2.3. Intellectual Property Protection

2.4. Service Innovation

2.5. Intellectual Property Protection (IPP) as a Mediating Role

2.6. Continuous Innovation Performance (CIP) as a Mediating Role

2.7. The Moderating Role of Open Innovation (OI)

3. Method

3.1. Samples and Data Collection

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

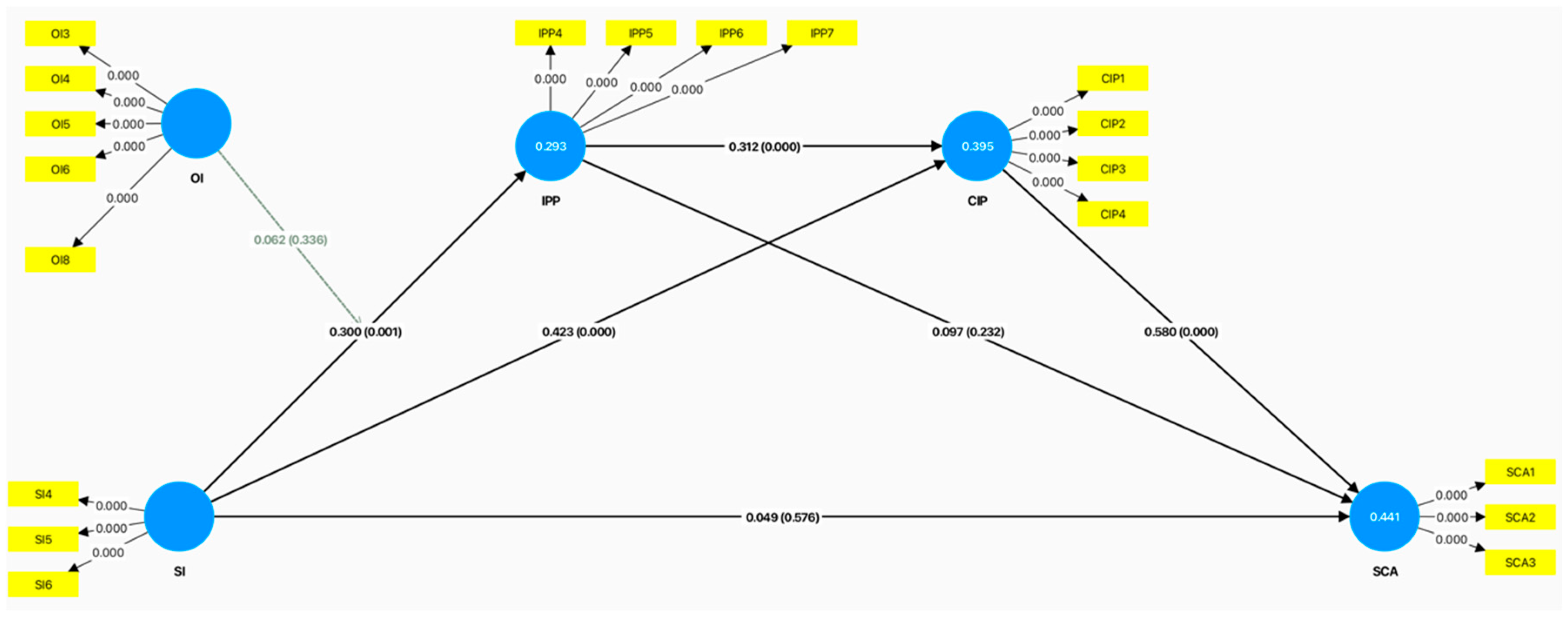

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

4.3. Mediating Effects

4.4. Moderating Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Suggestions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SI | Service innovation |

| OI | Open innovation |

| IPP | Intellectual property protection |

| CIP | Continuous innovation performance |

| SCA | Sustainable competitive advantage |

| IPPM | Intellectual property protection method |

| SME | Small and medium-sized enterprise |

| R&D | Research and development |

| CR | Composite reliability |

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

| Construct | Items | Ref. |

| Service innovation | The areas of expertise that your company offers | [23] |

| The speed in which your company delivers its products/services (e.g., accelerated delivery) | ||

| The flexibility of your company products or services (e.g., customization) | ||

| The ways in which the services your company provide are delivered | ||

| The ways in which the services your company provide are produced | ||

| The processes by which your company procures resources to offer products/services (e.g., introducing new recruitment standards) | ||

| The ways by which your company evaluates the quality of the products/services offered | ||

| The nature of technology that is used to produce or deliver products/services | ||

| Open innovation | We often acquire technological knowledge from outside for our use | [77,78] |

| We regularly search for external ideas that may create value for us | ||

| We have a sound system to search for and acquire external technology and intellectual property | ||

| We proactively reach out to external parties for better technological knowledge or products | ||

| We tend to build greater ties with external parties and rely on their innovation | ||

| We are proactive in managing outward knowledge flow | ||

| We make it a formal practice to sell technological knowledge and intellectual property in the market | ||

| We have a dedicated unit (i.e., gatekeepers, promoters) to commercialize knowledge assets (e.g., selling, cross-licensing patents, or spin-off) | ||

| We welcome others to purchase and use our technological knowledge or intellectual property | ||

| We seldom co-exploit technology with external organizations | ||

| Intellectual property protection | Having patents is important for our enterprise | [63] |

| Having trademarks is important for our enterprise | ||

| Having copyrights is important for our enterprise | ||

| Using trade secrets method is important for our enterprise | ||

| Using non-disclosure agreements and other contractual agreements methods is important for our enterprise | ||

| Using the product complexity method is important for our enterprise | ||

| Using the lead times method is important for our enterprise | ||

| Continuous Innovation performance | Reduce innovation risks | [63] |

| Reduce new product/process development cost | ||

| Reduce time to market | ||

| Introduce new or significantly improved products or services | ||

| Introduce new or significantly improved processes of producing our products or services | ||

| Sustainable competitive advantage | The innovations your company introduced enabled them to enjoy a superior market position for a reasonable period | [23] |

| Your company’s competitors could not easily match the advantages of the new products or services that they introduced | ||

| The new products or services your company introduced were a stepping stone for further development |

References

- Witell, L.; Snyder, H.; Gustafsson, A.; Fombelle, P.; Kristensson, P. Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Jung, S.; Kim, C. Product and service innovation: Comparison between performance and efficiency. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Y.-H.; Chou, Y.-H. Modeling the impact of service innovation for small and medium enterprises: A system dynamics approach. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2018, 82, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasi, J.; Rantala, T. Services, open innovation and intellectual property. In VTT Symposium on Service Innovation; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2011; p. 291. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282820358_Services_open_innovation_and_intellectual_property (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Lai, E.L.-C. International intellectual property rights protection and the rate of product innovation. J. Dev. Econ. 1998, 55, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Nosella, A.; Soranzo, B. The impact of formal and informal appropriability regimes on SME profitability in medium high-tech industries. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 27, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mu, R.; Hu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Intellectual property protection, technological innovation and enterprise value—An empirical study on panel data of 80 advanced manufacturing SMEs. Cogn. Syst. Res. 2018, 52, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Lee, K.; Yang, J.Y. How do intellectual property rights and government support drive a firm’s green innovation? The mediating role of open innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 317, 128422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z.; Li, P.; Sun, P. How do intellectual property rights affect green technological innovation? Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A.J. The paradox of openness: Appropriability, external search and collaboration. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freel, M.; Robson, P.J. Appropriation strategies and open innovation in SMEs. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 578–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Green, L. Patents in the Service Industries; Fraunhofer Institute Systems and Innovation Research: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paallysaho, S.; Kuusisto, J. Intellectual property protection as a key driver of service innovation: An analysis of innovative KIBS businesses in Finland and the UK. Int. J. Serv. Technol. Manag. 2008, 9, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päällysaho, S.; Kuusisto, J. Informal ways to protect intellectual property (IP) in KIBS businesses. Innovation 2011, 13, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Flikkema, M.; Castaldi, C.; de Man, A.-P. The effectiveness of appropriation mechanisms for sustainable innovations from small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 374, 133921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L. A management perspective. In The Management of Intellectual Property; Elgaronline: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 66–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sveiby, K.E.; Risling, A. The Know-How Company; Liber: Malmo, Sweden, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, P.H. A brief history of the ICM movement. In Value-Driven Intellectual Capital: How to Convert Intangible Corporate Assets into Market Value; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 238–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y. The effects of customer and supplier involvement on competitive advantage: An empirical study in China. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1384–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, E. How intellectual property management capability and network strategy affect open technological innovation in the Korean new information communications technology industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; Weerawardena, J.; McColl-Kennedy, J.R. Competing through service innovation: The role of bricolage and entrepreneurship in project-oriented firms. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R.; Nyadzayo, M.; Mohan, M. Service innovation and adoption in industrial markets: An SME perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.-H.; Ha, J.-L.; Wang, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-L. A study of the relationship among service innovation, customer value and customer satisfaction: An empirical study of the hotel industry in Taiwan. Int. J. Organ. Innov. 2012, 4, 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Lianto, B.; Dachyar, M.; Soemardi, T.P. Continuous innovation: A literature review and future perspective. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2018, 8, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Coad, A.; Segarra, A. Firm growth and innovation. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lin, M.-J.J.; Chang, C.-H. The positive effects of relationship learning and absorptive capacity on innovation performance and competitive advantage in industrial markets. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Nelson, R.; Walsh, J.P. Protecting Their Intellectual Assets: Appropriability Conditions and Why US Manufacturing Firms Patent (or Not); NBER Working Papers 7552; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. The logic of open innovation: Managing intellectual property. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, M.; Greco, M.; Cricelli, L. A framework of intellectual property protection strategies and open innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Joo, S.H.; Kim, Y. The complementary effect of intellectual property protection mechanisms on product innovation performance. RD Manag. 2018, 48, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Terziovski, M. Intellectual property appropriation strategy and its impact on innovation performance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2016, 20, 1650016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, L.; Filippini, R.; Nosella, A. Protecting intellectual property to enhance firm performance: Does it work for SMEs? Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2016, 14, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, S.J.; Sohn, S.Y. Perceived importance of intellectual property protection methods by Korean SMEs involved in product innovation and their value appropriation. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2023, 61, 2561–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallouj, F. Innovation in the Service Economy: The New Wealth of Nations; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, R.; Miles, I. Innovation, measurement and services: The new problematique. In Innovation Systems in the Service Economy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, C.M.; Prajogo, D.I. Service innovation and performance in SMEs. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2012, 32, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, W.U.; Nisar, Q.A.; Wu, H.-C. Relationships between external knowledge, internal innovation, firms’ open innovation performance, service innovation and business performance in the Pakistani hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Nambisan, S. Service innovation. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.L.; Cham, T.H.; Dent, M.M.; Lee, T.H. Service innovation: Building a sustainable competitive advantage in higher education. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2019, 10, 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.L.; Cheong, C.B.; Rizal, H.S. Service innovation in Malaysian banking industry towards sustainable competitive advantage through environmentally and socially practices. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 224, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-S.; Tsou, H.-t. Information technology adoption for service innovation practices and competitive advantage: The case of financial firms. Inf. Res. Int. Electron. J. 2007, 12, n3. [Google Scholar]

- Madhani, P.M. Resource based view (RBV) of competitive advantage: An overview. In Resource Based View: Concepts and Practices; Madhani, P., Ed.; Icfai University Press: Hyderabad, India, 2009; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Grimpe, C.; Hussinger, K. Resource complementarity and value capture in firm acquisitions: The role of intellectual property rights. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1762–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rylková, Ž.; Chobotová, M. Protection of intellectual property as a means of evaluating innovation performance. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 14, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xiu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, J. Intellectual property protection and enterprise innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 62, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Y.; Boadu, F. Distributed innovation, knowledge re-orchestration, and digital product innovation performance: The moderated mediation roles of intellectual property protection and knowledge exchange activities. J. Knowl. Manag. 2023, 27, 2686–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Militaru, G. The moderating effect of intellectual property rights on relationship between innovation and company performance in manufacturing sector. Procedia Manuf. 2019, 32, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yu, X.; Liu, X. Obtaining a sustainable competitive advantage from patent information: A patent analysis of the graphene industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjet, A.; Zagoracz, I.; Milkovic, M.; Kozina, G. Intellectual Property Rights as A Source of Competitive Advantage. In Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2022; pp. 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.F.; Dyerson, R.; Wu, L.Y.; Harindranath, G. From temporary competitive advantage to sustainable competitive advantage. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, 617–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonsela, N.S.; Mukwakungu, S.C.; Mbohwa, C. Continuous innovation as fundamental enabler for sustainable business practices. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 8, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Teixeira, E.; Werther, W.B., Jr. Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuncoro, W.; Suriani, W.O. Achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product innovation and market driving. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Open innovation in practice: An analysis of strategic approaches to technology transactions. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2008, 55, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Crowther, A.K. Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. RD Manag. 2006, 36, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Intellectual property and open innovation: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2010, 52, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bican, P.M.; Guderian, C.C.; Ringbeck, A. Managing knowledge in open innovation processes: An intellectual property perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1384–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunningham, N. Regulating small and medium sized enterprises. J. Envtl. L. 2002, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-P.; Chou, C. The impact of open innovation on firm performance: The moderating effects of internal R&D and environmental turbulence. Technovation 2013, 33, 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Aloini, D.; Lazzarotti, V.; Manzini, R.; Pellegrini, L. IP, openness, and innovation performance: An empirical study. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1307–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair Jr, J.F.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Fassott, G. Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 713–735. [Google Scholar]

- Rajapathirana, R.J.; Hui, Y. Relationship between innovation capability, innovation type, and firm performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2018, 3, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurmelinna Laukkanen, P.; Ritala, P. Protection for profiting from collaborative service innovation. J. Serv. Manag. 2010, 21, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Voss, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. Modes of service innovation: A typology. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 1358–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.U.; Yu, F. Do formal and informal protection methods affect firms’ productivity and financial performance? J. World Intellect. Prop. 2018, 21, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brem, A.; Nylund, P.A.; Hitchen, E.L. Open innovation and intellectual property rights: How do SMEs benefit from patents, industrial designs, trademarks and copyrights? Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toivonen, T. Continuous innovation–combining Toyota Kata and TRIZ for sustained innovation. Procedia Eng. 2015, 131, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soosay, C.A.; Chapman, R.L. An empirical examination of performance measurement for managing continuous innovation in logistics. Knowl. Process Manag. 2006, 13, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelin-Palmqvist, H.; Sandberg, B.; Mylly, U.-M. Intellectual property rights in innovation management research: A review. Technovation 2012, 32, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbertson, R.W.; Furseth, P.I. Digital services and competitive advantage: Strengthening the links between RBV, KBV, and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Items | Num | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of employees | Less than 20 | 91 | 57.59% |

| 21–50 | 56 | 35.44% | |

| 51–200 | 11 | 6.96% | |

| Establish time | Less than 1 year | 104 | 65.82% |

| 1–2 years | 32 | 20.25% | |

| 3–5 years | 17 | 10.76% | |

| 5–10 years | 5 | 3.16% | |

| More than 10 years | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Job position | CEO | 121 | 76.58% |

| Sales executive | 3 | 1.90% | |

| Operations supervisor | 8 | 5.06% | |

| Technical supervisor | 6 | 3.80% | |

| Financial supervisor | 4 | 2.53% | |

| Head of personnel and administration | 16 | 10.13% | |

| Industries | Retail | 5 | 3.16% |

| Manufacturing | 12 | 7.59% | |

| Internet and technological services | 64 | 40.51% | |

| Telecommunication | 25 | 15.82% | |

| Financial Services | 19 | 12.03% | |

| Education | 13 | 8.23% | |

| Transport and transportation | 16 | 10.13% | |

| Sports and entertainment | 4 | 2.53% | |

| Others | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Total | 158 | 100.00% | |

| Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | CIP1 | 0.768 | 0.857 | 0.903 | 0.700 |

| CIP2 | 0.858 | ||||

| CIP3 | 0.861 | ||||

| CIP4 | 0.856 | ||||

| IPP | IPP4 | 0.793 | 0.817 | 0.879 | 0.645 |

| IPP5 | 0.795 | ||||

| IPP6 | 0.805 | ||||

| IPP7 | 0.819 | ||||

| OI | OI3 | 0.765 | 0.841 | 0.887 | 0.611 |

| OI4 | 0.814 | ||||

| OI5 | 0.730 | ||||

| OI6 | 0.848 | ||||

| OI8 | 0.746 | ||||

| SCA | SCA1 | 0.883 | 0.861 | 0.915 | 0.782 |

| SCA2 | 0.900 | ||||

| SCA3 | 0.870 | ||||

| SI | SI4 | 0.808 | 0.772 | 0.868 | 0.687 |

| SI5 | 0.842 | ||||

| SI6 | 0.836 | ||||

| CIP | IPP | OI | SCA | SI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIP | 0.837 | ||||

| IPP | 0.502 | 0.803 | |||

| OI | 0.444 | 0.461 | 0.782 | ||

| SCA | 0.657 | 0.410 | 0.510 | 0.884 | |

| SI | 0.563 | 0.449 | 0.436 | 0.419 | 0.829 |

| CIP | IPP | OI | SCA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPP | 0.603 | |||

| OI | 0.509 | 0.549 | ||

| SCA | 0.756 | 0.491 | 0.594 | |

| SI | 0.690 | 0.563 | 0.537 | 0.514 |

| Hypothesis | β | t-Value | p Values | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CIP -> SCA | 0.580 | 6.690 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2 | IPP -> CIP | 0.312 | 4.235 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3 | IPP -> SCA | 0.097 | 1.194 | 0.232 | NS |

| H4 | SI -> IPP | 0.300 | 3.340 | 0.001 | Supported |

| H5 | SI -> CIP | 0.423 | 5.216 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H6 | SI -> SCA | 0.049 | 0.560 | 0.576 | NS |

| Hypothesis | IV | MV | DV | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H7 | SI | IPP | CIP | 0.094 (2.367) * | 0.094 (2.367) * | 0.517 (7.312) *** | 18.18% | NS |

| H8 | SI | IPP | SCA | 0.329 (5.790) *** | 0.029 (1.104) | 0.378 (4.690) *** | 7.67% | NS |

| H9 | SI | CIP | SCA | 0.329 (5.790) *** | 0.246 (4.514) *** | 0.378 (4.690) *** | 65.08% | Supported |

| Interaction Terms | 2.5% Lower Bound | 97.5% Upper Bound | Zero Included | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OI × SI -> IPP | −0.06 | 0.192 | Yes | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Yusof, R.N.R.; Jaharuddin, N.S. Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094093

Wang X, Yusof RNR, Jaharuddin NS. Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):4093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094093

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xi, Raja Nerina Raja Yusof, and Nor Siah Jaharuddin. 2025. "Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 4093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094093

APA StyleWang, X., Yusof, R. N. R., & Jaharuddin, N. S. (2025). Driving SMEs’ Sustainable Competitive Advantage: The Role of Service Innovation, Intellectual Property Protection, Continuous Innovation Performance, and Open Innovation. Sustainability, 17(9), 4093. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17094093