Appropriate Planning Policies for the Development of Accessible and Inclusive Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The State of the Art

2.1. The Advantages of Accessible Tourism and Prospects for the Future

2.2. The Importance of Training in the Design of an Accessible Tourism Offer

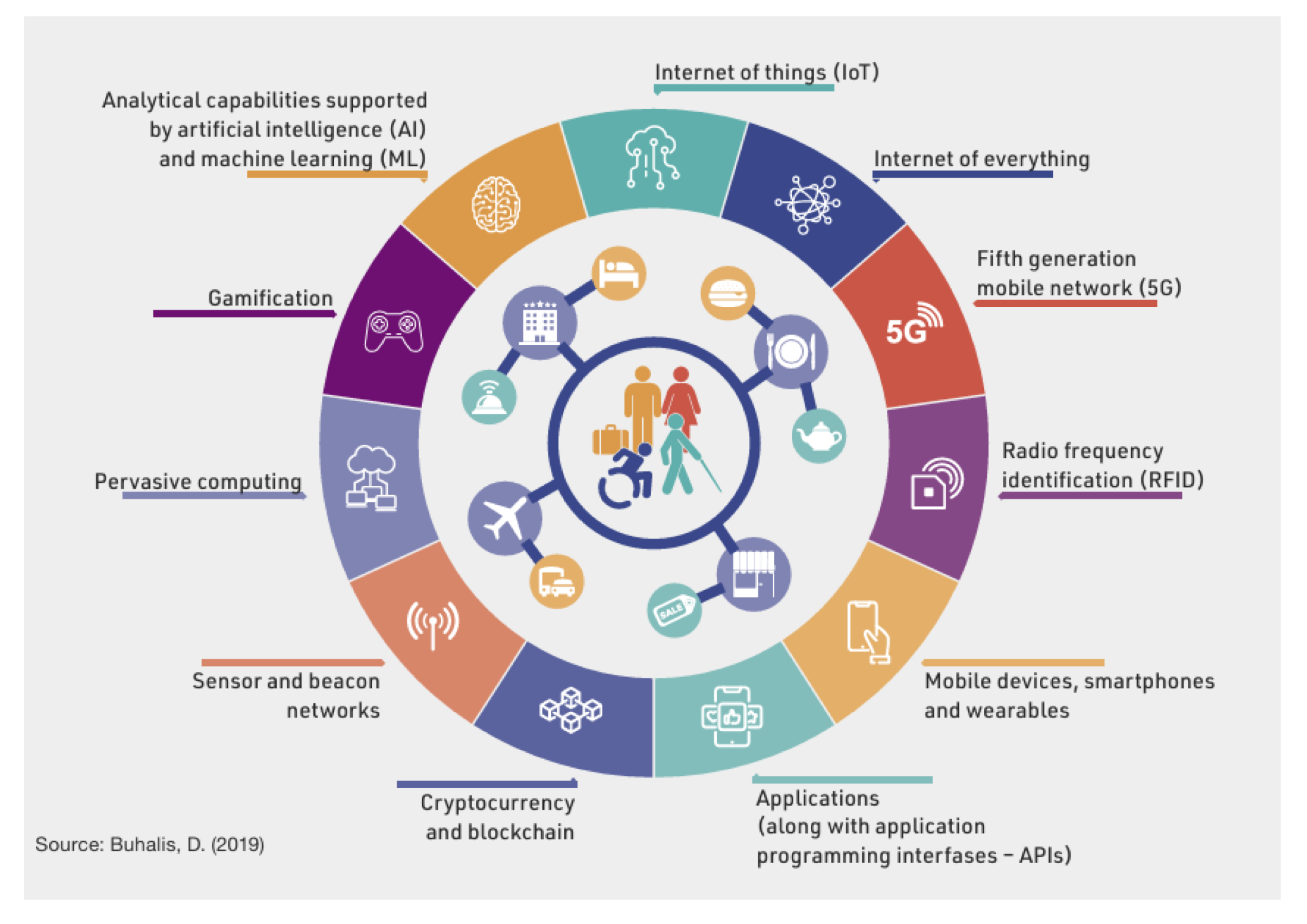

2.3. Smart Tourism for Inclusion

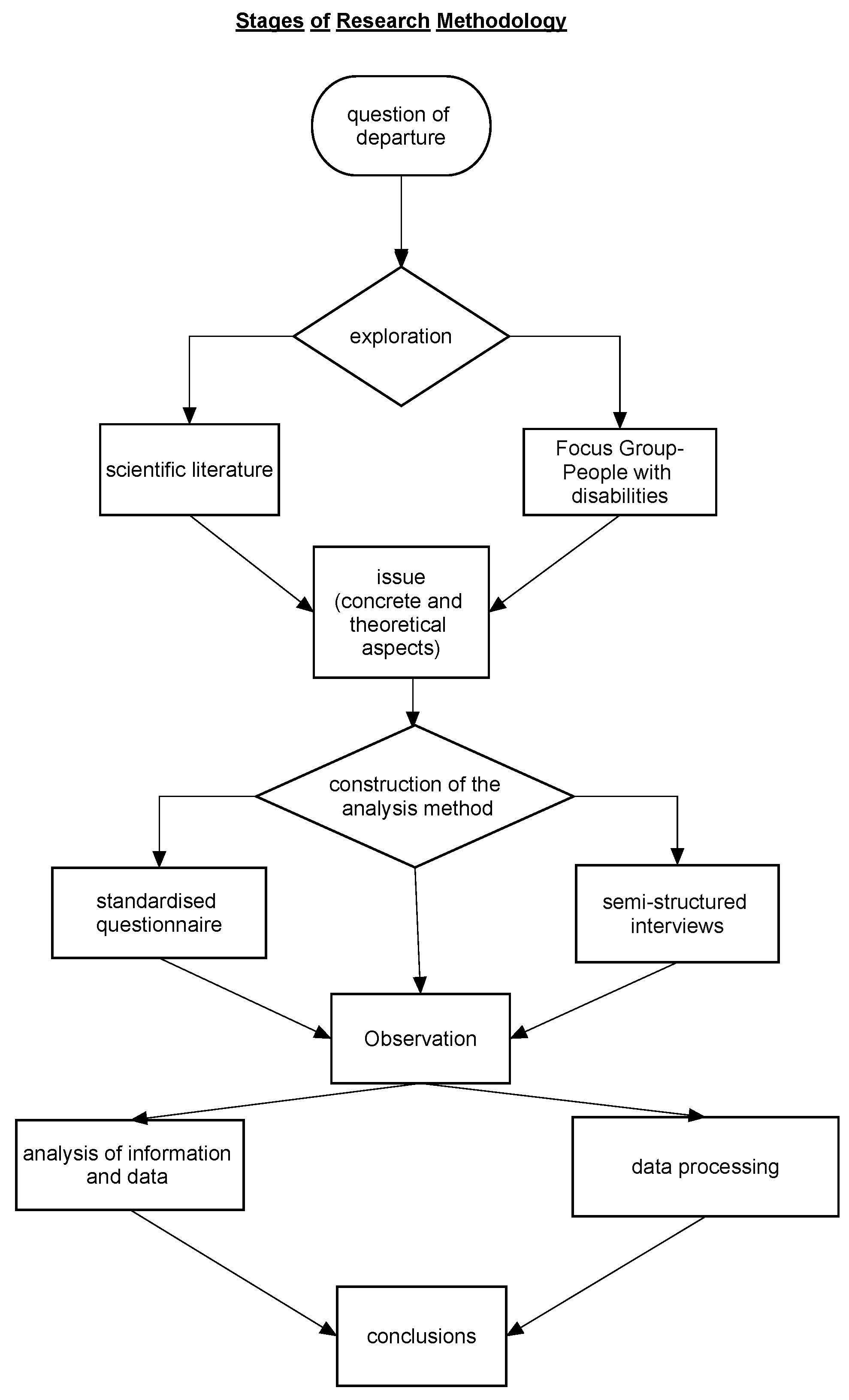

3. Materials and Methods

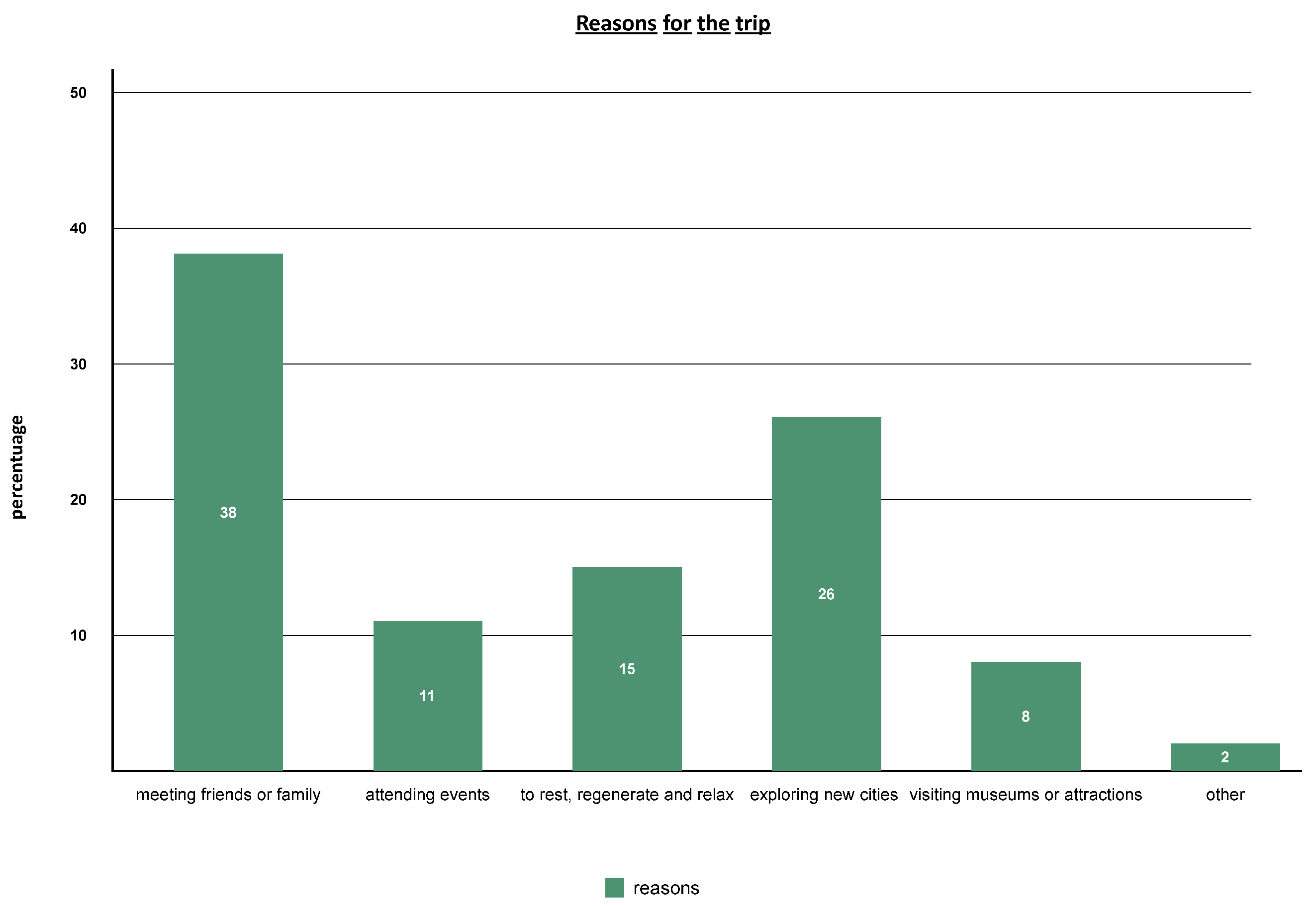

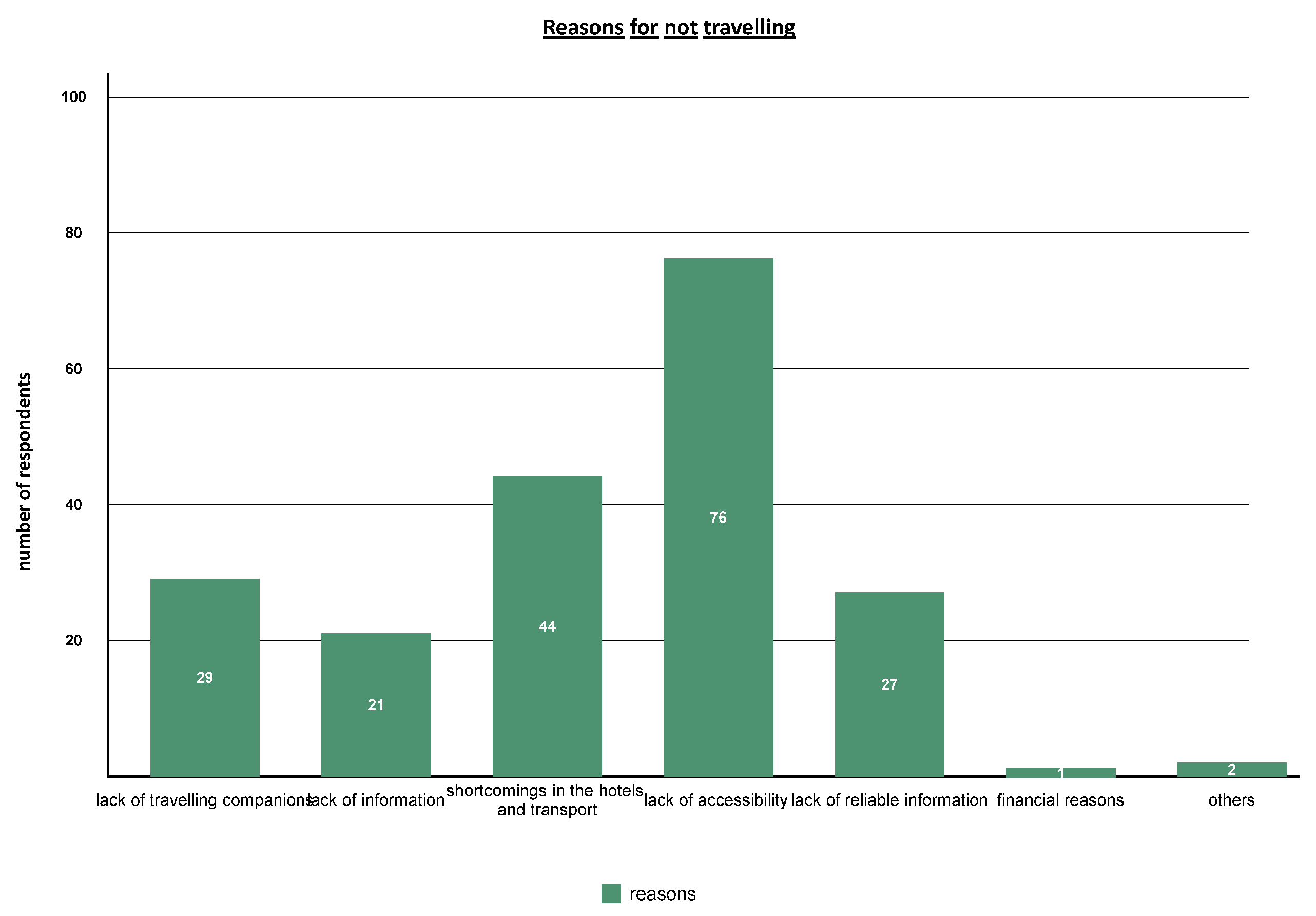

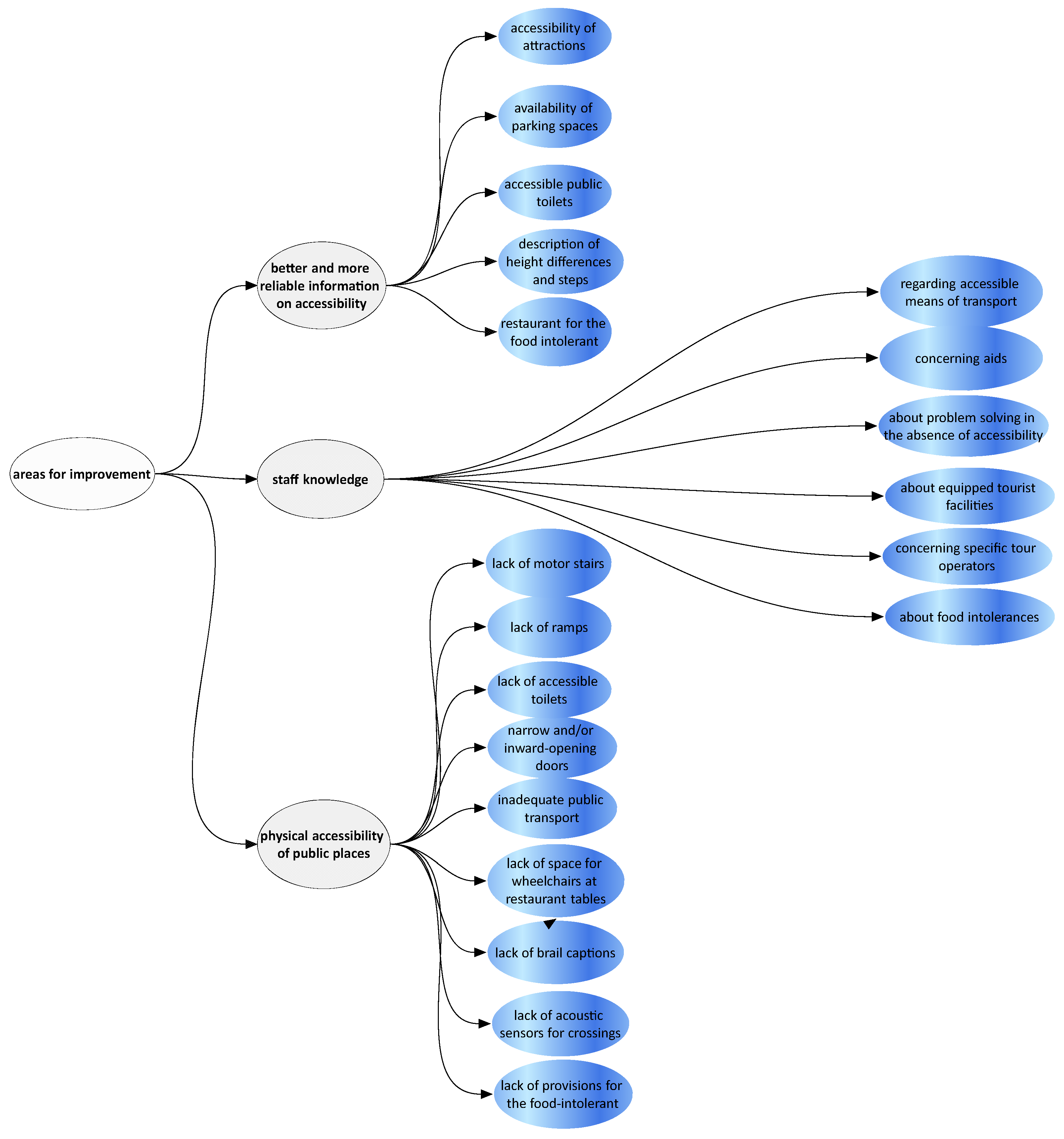

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Factors to Consider for Inclusive and Disability-Oriented Tourism Planning

5.2. Importance of Accessible Tourism in Terms of Socio-Economic Benefits

5.3. Triangulation

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowtell, J. Assessing the value and market attractiveness of the accessible tourism industry in Europe: A focus on major travel and leisure companies. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, M.K.-S.; McKercher, B.; Packer, T.L. Traveling with a disability: More than an Access Issue. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 946–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. World Tourism Barometer; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, S.; Dickson, T.J. A Whole-of-Life Approach to Tourism: The Case for Accessible Tourism Experiences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2009, 1, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Italy. Turismo in Italia: Numeri e potenziali di sviluppo. In Questioni di Economia e Finanza, (Occasional Papers); luglio 2019, n. 505; Banca d’Italia: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Economic Impact on Travel Patterns of Accessible Tourism in Europe–Final Report; DG Enterprise and Industry: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aslasken, F.; Bergh, S.; Bgringa, O.R.; Heggem, E.K. Universal Design, Planning and Design for All; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cocco, V. Pronti a (ri)partire. In Dal Turismo Accessibile; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J.J.; Baker, H.B. Assessing the Travel-Related Behaviors of the Mobility-Disabled Consumer’. J. Travel Res. 2001, 40, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, V.; Buhalis, D. Accessibility: A Key Objective for the Tourism Industry. In Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues; Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cannas, R. Politiche Pubbliche per la Stagionalità del Turismo da una Prospettiva Territoriale. Casi di Studio in Scozia in Sardegna. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bologna: Bologna, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D. Technology in tourism-from information communication technologies to eTourism and smart tourism towards ambient intelligence tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2019, 75, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyfanti, K.; Sdrali, D. Creativity and Sustainable development: A proposal to transform a Small Greek Island into a creative town. In Strategic, Innovative Marketing and Tourism; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 377–385. [Google Scholar]

- Gelter, H.; Digital Tourism and Analysis of Digital Trends in Tourism and Customer Digital Mobile Behavior. Visit Arctic Europe Project. 2017. Available online: https://archipelagobusiness.nu/rapporter/digital-tourism-an-analysis-of-digital-trends-in-tourism-and-customer-digital-mobile-behaviour (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Osservatorio Sull’innovazione Digitale nel Turismo di Milano. Report Federturismo, Confindustria, Ufficio Stampa Osservatori Digital Innovation del Politecnico di Milano. 2019. Available online: https://www.osservatori.net/comunicato/travel-innovation/mercato-digitale-del-turismo-in-italia-crescono-gli-acquisti-online-di-viaggi-e-trasporti-soprattutto-da-mobile/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- World Tourism Organization. International Tourism Highlights; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, S.; Buhalis, D. Introduction: From Disabled Tourists to Accessible Tourism. In Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues; Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Darcy, S.; Buhalis, D. Conceptualising Disability: Medical, Social, WHO ICF, Dimensions and Levels of Support Needs. In Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues; Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Darcy, S.; Ambrose, I. Best Practice in Accessible Tourism: Inclusion, Disability, Ageing Population and Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose, I. European Policies for Accessible Tourism. In Best Practice in Accessible Tourism: Inclusion, Disability, Ageing Population and Tourism; Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., Ambrose, I., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Tonawanda, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pigliucci, M. La pianificazione strategica del turismo nel quadro delle politiche di sviluppo territoriale. In AAVv. Riprogrammare la Crescita Territoriale Turismo Sostenibile, Rigenerazione e Valorizzazione del Patrimonio Culturale; Patron editore: Bologna, Italy, 2021; ISBN 9788855535175. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Sinarta, Y. Real-time co-creation and nowness service: Lesson from tourism and hospitality. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J.C.; Humphreys, C. The Business of Tourism. (Tionde Upplagan); Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Card, J.-A.; Cole, S.-T.; Humphrey, H. A comparison of the Accessibility and Attitudinal Barriers Model: Travel providers and travelers with physical disabilities. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2006, 11, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Darcy, S. Accessible Tourism: Concepts and Issues; Buhalis, D., Darcy, S., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, M.d.F.; Gosling, M.d.S.; Almeida, A.S.A.d. Tourism experiences: Core processes of memorable trips. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Co-creation of Tourist Experience: Scope, Definition and Structure. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism; Prebensen, N.K., Chen, J.S., Uysal, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bjork, P. Tourist experience value: Tourist experience and satisfaction. In Creating Experience Value in Tourism, 2nd ed.; Prebensen, N.K., Chen, J.S., Uysal, M., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Darcy, S. Re-conceptualizing barriers to travel by people with disabilities. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulou, E.; Darcy, S.; Ambrose, I.; Buhalis, D. Accessible tourism futures: The world we dream to live in and the opportunities we hope to have. J. Tour. Futures 2015, 1, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decrop, A. Destination choice sets-An inductive longitudinal approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Cole, S.; Chancellor, C. Understanding leisure travel motivations of travelers with acquired mobility impairments. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.F. Tourist information search. In Handbook of Tourist Behavior: Theory & Practice; Kozak, M., Decrop, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, T.-D.; Gonzalez, E.-A.; Darcy, S. Accessible tourism online resources: A Northern European perspective. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2019, 19, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, J.; Darcy, S.; Packer, T. The embodied tourist experiences of people with vision impairment: Management implications beyond the visual gaze. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.J. Practical Tourism Research, 2nd ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson, S.; Stahl, A. Accessibility, usability and universal design—Positioning and definition of concepts describing person-environment relationships. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Disability | Barriers to Use | Factors That Support Accessibility | Strategic Policies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor and Sensory | Urban barriers | Use of assistive technologies | Policies to improve accessible pedestrian paths and access to cultural sites |

| Motor and Sensory | Confined spaces characterized by limited accessibility (e.g., enclosed, narrow, small, with difficult entry and exit, etc.). | Access that does not present risks or danger | Removal of architectural barriers |

| Motor and Sensory | Transportation barriers | Inclusive public transportation for ease of access | Policies to make transportation accessible with technology and voice announcements |

| Motor and Sensory | Barriers to use | Targeted design solutions | Policies aimed at reducing distances and limiting the use of accommodation facilities |

| Motor and Sensory | Information barriers | Information | Community involvement |

| Motor and Sensory | Cultural barriers | Training | Organization of courses for tourism operators |

| Sensory | Language barriers | Assistive technologies | Adapting the accessibility of cultural facilities with Braille or sign language |

| Food disabilities | Food barriers | Possibilities of food choices | Awareness campaigns for tourism operators in general and for catering operators |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quattrone, G. Appropriate Planning Policies for the Development of Accessible and Inclusive Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093972

Quattrone G. Appropriate Planning Policies for the Development of Accessible and Inclusive Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093972

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuattrone, Giuliana. 2025. "Appropriate Planning Policies for the Development of Accessible and Inclusive Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093972

APA StyleQuattrone, G. (2025). Appropriate Planning Policies for the Development of Accessible and Inclusive Tourism. Sustainability, 17(9), 3972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093972