Moderated Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Innovation Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Role of Inclusive Leadership

1.2. Role of Employee Introspection

1.3. Role of Sense of Accomplishment

1.4. Psychological Safety Status as a Moderator

1.5. Organizational Support Status as a Moderator

2. Method and Variables

2.1. Hypothesis

2.2. Method

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Reliability and Validity Tests

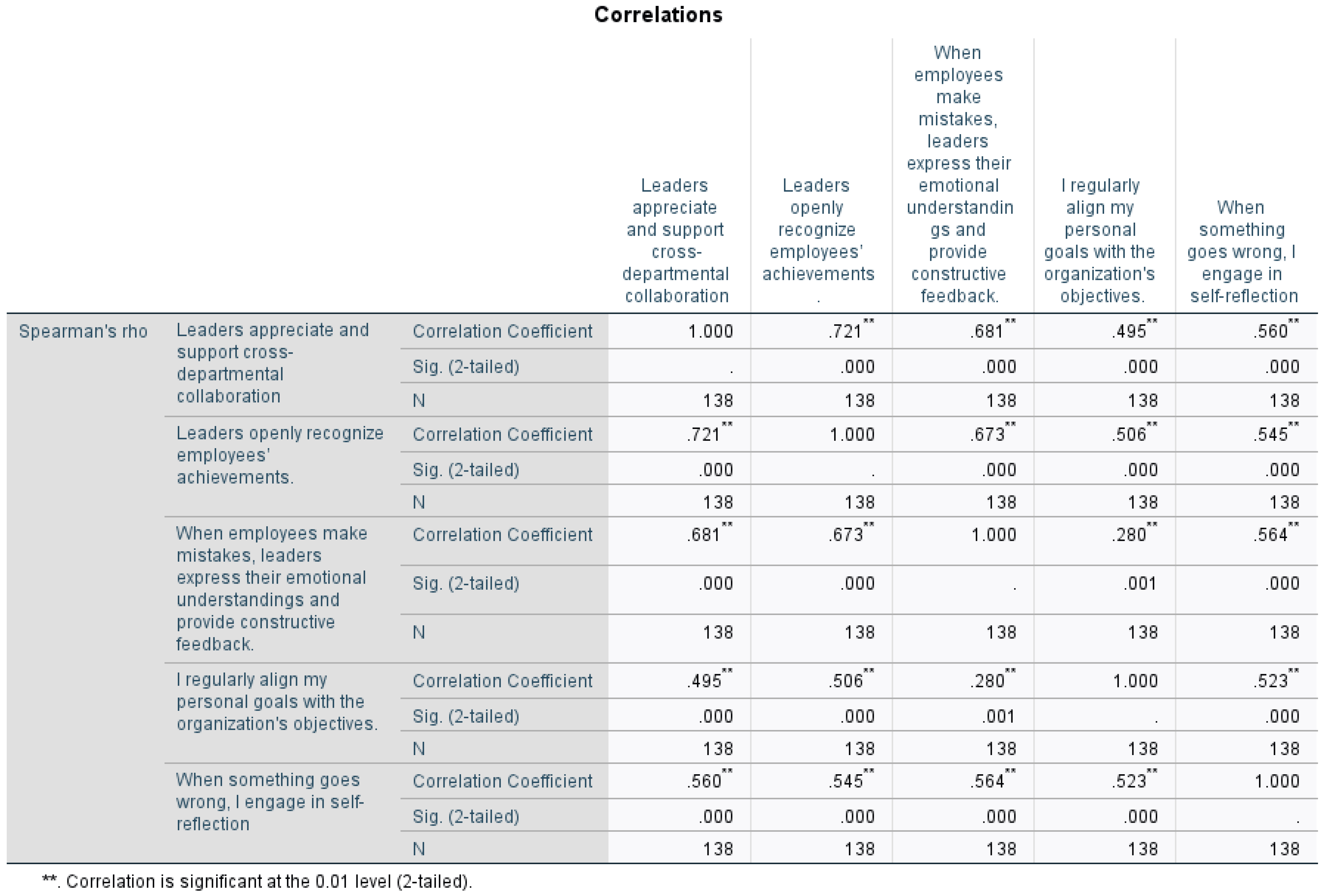

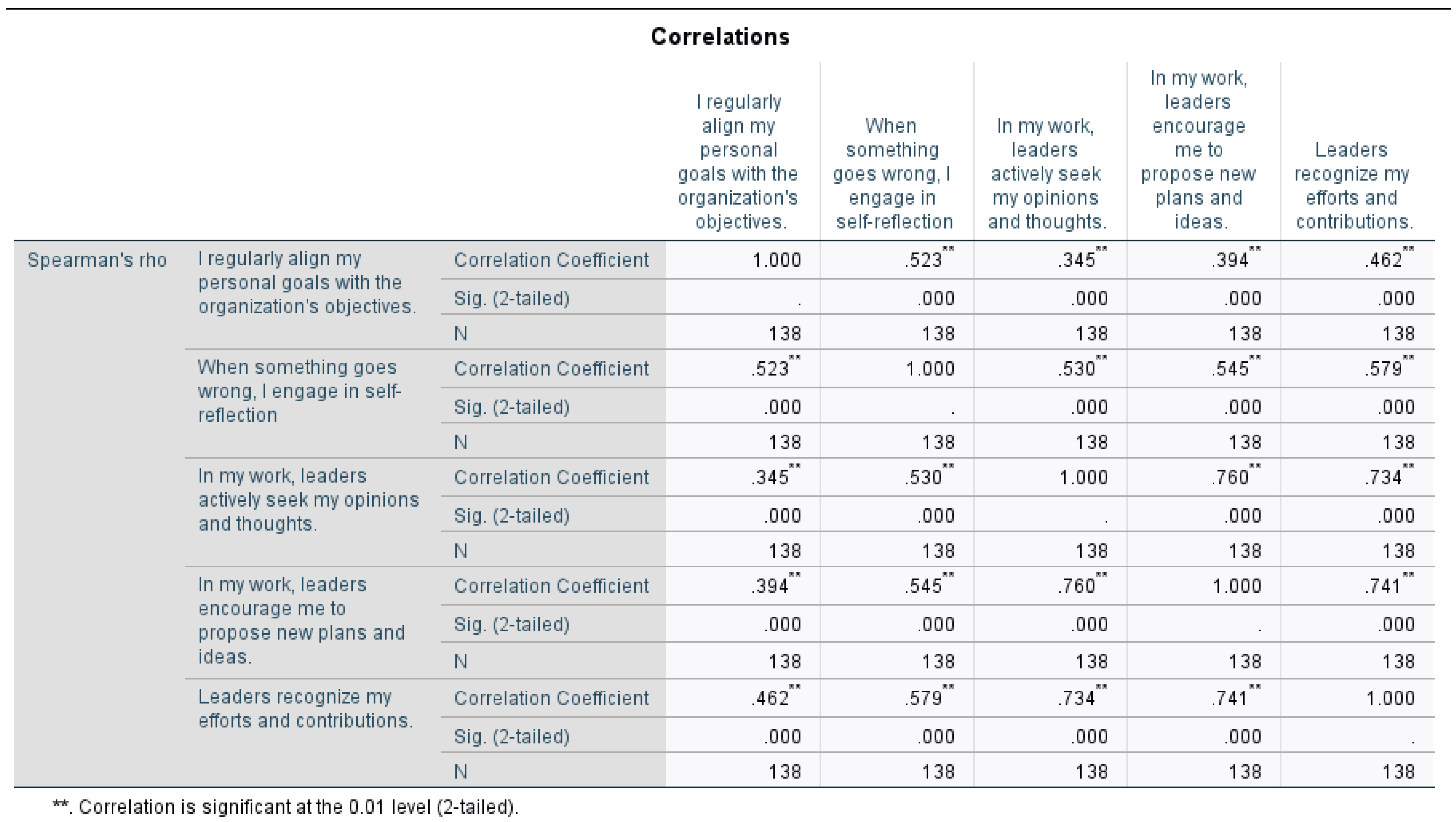

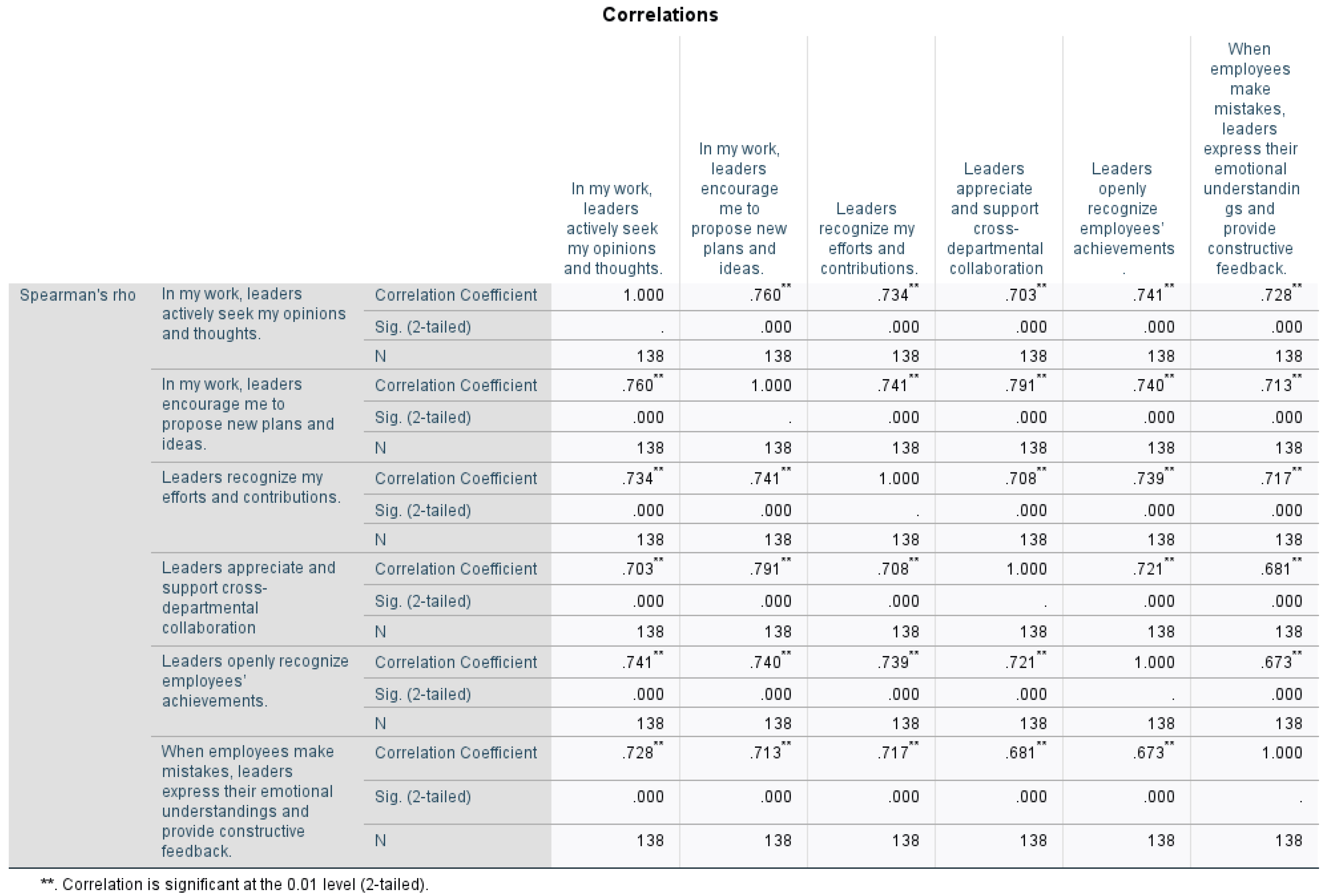

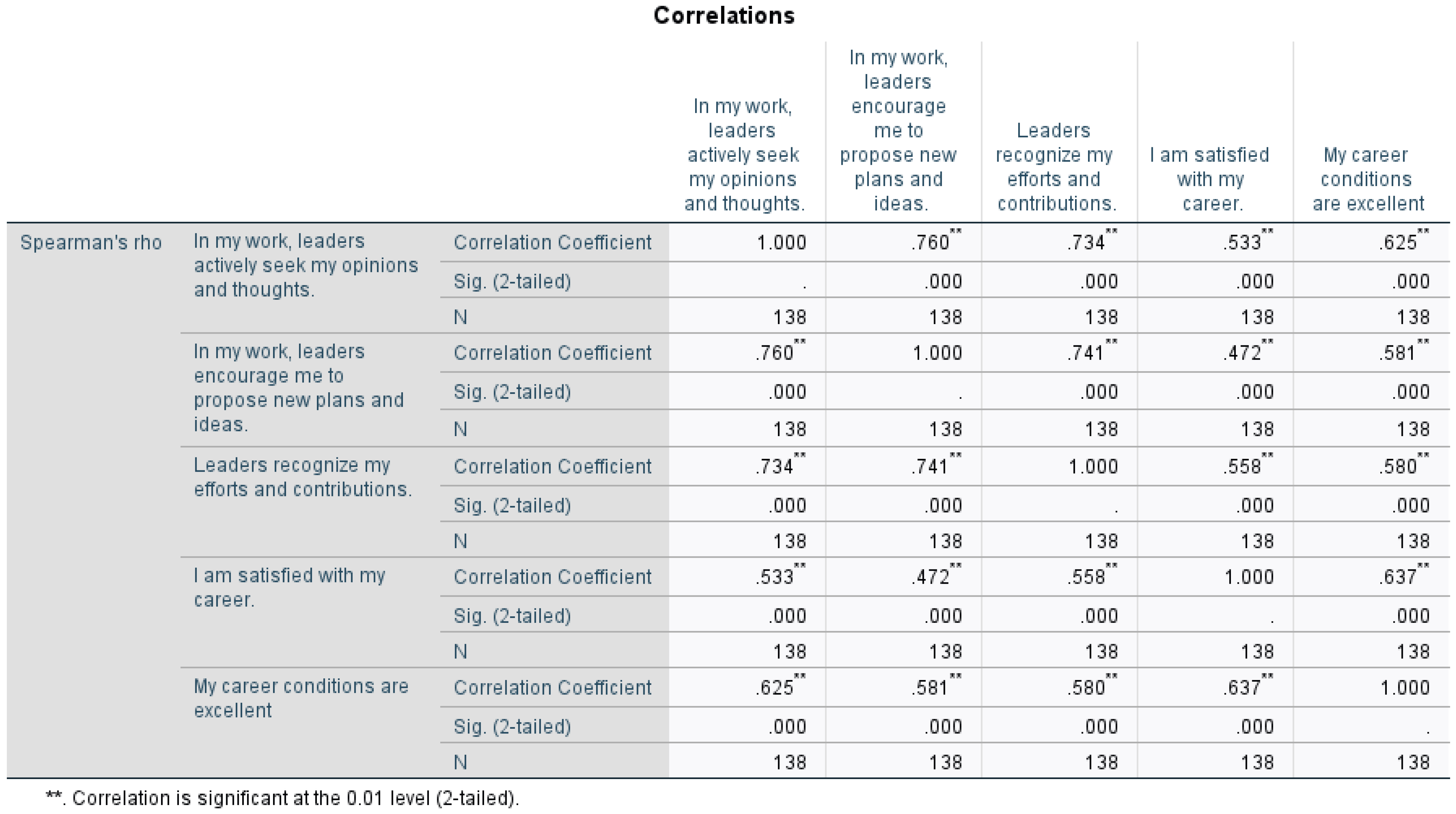

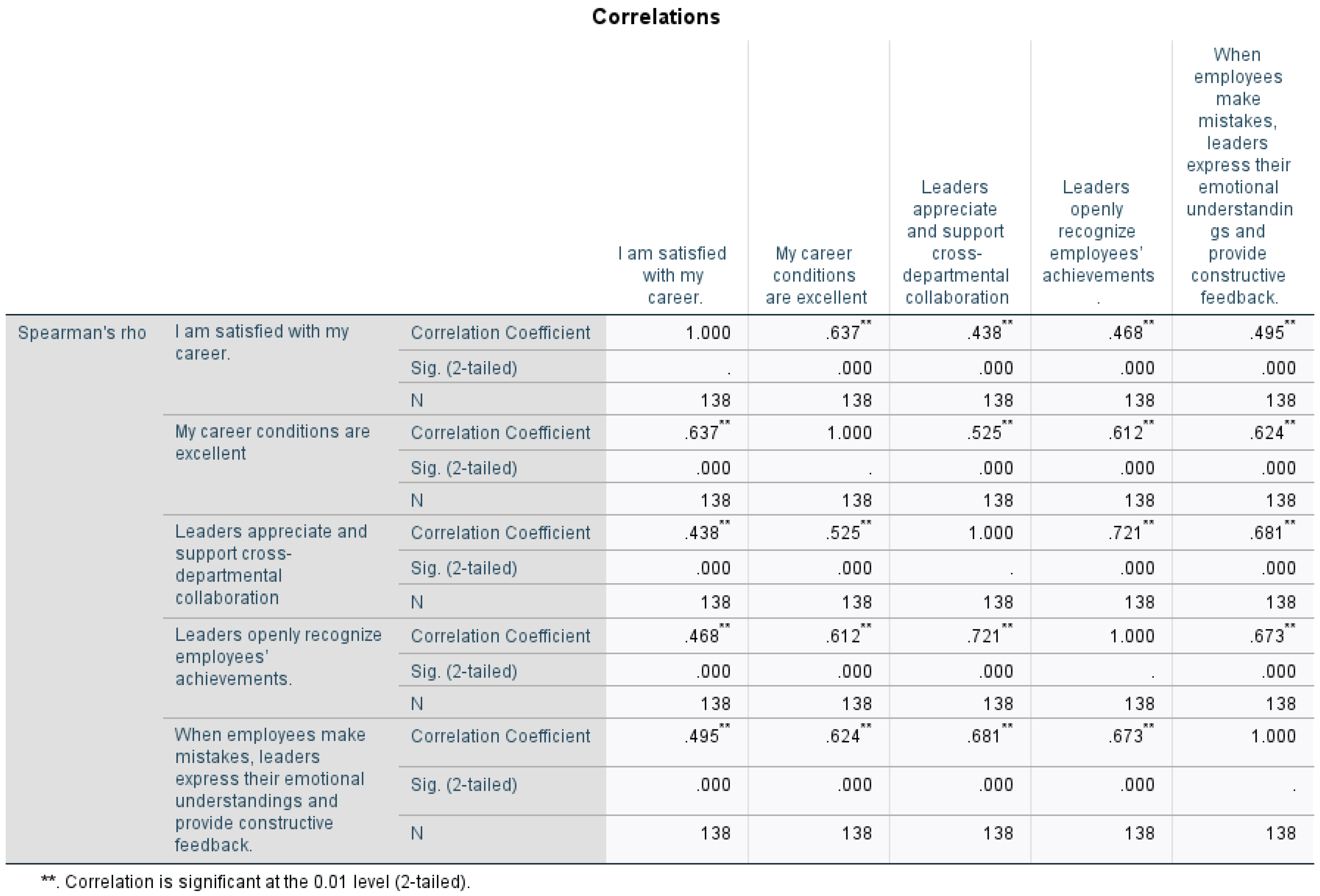

2.3.2. Correlational Analysis

3. Discussion on Results

3.1. Mediation Analysis

3.2. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

Appendix A. Variables and Scales

- I am satisfied with my career.

- My career conditions are excellent.

- 3.

- My organization strongly considers my goals.

- 4.

- My organization strongly considers my values.

- 5.

- In my work, leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts.

- 6.

- Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions.

- 7.

- In my work, leaders encourage me to propose new plans and ideas.

- 8.

- Leaders appreciate and support cross-departmental collaboration.

- 9.

- Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements.

- 10.

- When employees make mistakes, leaders express their emotional understanding and provide constructive feedback.

- 11.

- When something goes wrong, I engage in self-reflection.

- 12.

- I regularly align my personal goals with the organization’s objectives.

- 13.

- Leaders treat employees fairly.

- 14.

- Leaders emphasize fairness and justice in team management.

| Variables | Sense of Accomplishment | Organizational Support | Innovation Behavior | Inclusive Leadership | Employee Introspection | Psychological Safety | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scales |

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. Jackson Personality Inventory Manual; Research Psychologists Press: Goshen, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Motivating creativity in organizations: On doing what you love and loving what you do. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 40, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Lucianetti, L. Within-individual increases in innovative behavior and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: A social–cognitive theory perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 682–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.J.; Zhang, G.L. Research on the impact of work motivation on individual innovative behavior. Soft Sci. 2007, 124–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.D.; Peng, J.S. The impact of organizational innovation atmosphere on employee innovation behavior: The mediating role of innovation self-efficacy. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2010, 13, 30–41. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, J.T. A Study on the Influence Process of Organizational Innovation Atmosphere on Employee Innovation. China Soft Sci. 2010, 133–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tu, X.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; He, X.; Zhang, Q. Critical reflection, innovative process investment, and innovative behavior: An empirical study from employees of technology-based enterprises. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2017, 38, 126–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kleysen, R.F.; Street, C.T. Toward a multi-dimensional measure of individual innovative behavior. J. Intellect. Cap. 2001, 2, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitello, S.; Mithaug, D.E. Inclusive Schooling: National and International Perspectives; Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pless, N.; Maak, T. Building an inclusive diversity culture: Principles, processes and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 54, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 7, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Ziv, E. Inclusive leadership and employee involvement in creative tasks in the workplace: The mediating role of psychological safety. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, E. Inclusive Leadership: The Essential Leader-Follower Relationship; Routledge Academic: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nishii, L.H.; Mayer, D.M. Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader–member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1412–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.X. Exploring the Path to Achieving Inclusive Growth: Based on the Perspective of Inclusive Leadership. Frontier 2011, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.C. The impact of inclusive leadership style on team performance—Mediated by employee self-efficacy. Res. Manag. 2014, 35, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.J. The concept of inclusive leadership and its implementation path. Leadersh. Sci. 2014, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, S.T. Analysis and Future Prospects of the Frontiers in Inclusive Leadership Research. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2014, 36, 55–64, 80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Research on the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Employee Proactive Behavior. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Locke, J. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoza, B. Letter 52 (Nagelate Schriften): To the Most Esteemed and Wise Hugo Boxel from B. D. S. In The Collected Works of Spinoza; Curley, E., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1674. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagawa, T. An analysis of reflective teaching. Educ. Res. 2000, 59–63+76. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.H. Research on the Relationship Between Reflection and Mental Health. Ph.D. Thesis, Huazhong Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2002. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Q. Dewey reflected on the rational spirit in moral theory. Morality Civil. 2014, 91–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- George, I.M.; Reed, T.F.; Ballard, K.A.; Colin, I.; Fielding, I. Contact with AIDS patients as a source of work-related distress: Effects of organizational and social support. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1998, 2, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; Folger, R.; Tesluk, P. Personality as a moderator in the relationship between fairness and retaliation. Acad. Manag. Discov. 1999, 42, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K. Serving unfair customers. Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.P.; Cao, X. The impact of improving self-esteem on behavioral performance. Psychol. Explor. 2015, 35, 239–243. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Sheaffer, Z.; Binyamin, G.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Shimoni, T. Transformational leadership and creative problem-solving: The mediating role of psychological safety and reflexivity. J. Creat. Behav. 2014, 48, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M.C.; Den Hartog, D.N.; Koopman, P.L. Reflexivity in teams: A measure and correlates. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreu, C.K.W.D. Team innovation and team effectiveness: The importance of minority dissent and reflexivity. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2002, 11, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, R.L.; McMinn, J.G. Group reflexivity and performance. In Advances in Group Processes; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmayr, R.; Weidinger, A.F.; Schwinger, M.; Spinath, B. The Importance of Students’ Motivation for Their Academic Achievement—Replicating and Extending Previous Findings. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Nakatani, H.; Hosoda, C.; Nonaka, Y.; Okanoya, K. Sense of Accomplishment Is Modulated by a Proper Level of Instruction and Represented in the Brain Reward System. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0168661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Wu, J. College Satisfaction, Sense of Achievement, Student Happiness and Sense of Belonging of Freshmen in Chinese Private Colleges: Mediation Effect of Emotion Regulation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magen-Nagar, N.; Cohen, L. Learning strategies as a mediator for motivation and a sense of accomplishment among students who study in MOOCs. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, T.A.; Perozzi, B.; Li, W. Sense of accomplishment: A global experience in student affairs and services. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2023, 60, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.P.; Jiang, J.J.; Klein, G.; Wang, E. Job burnout of the information technology worker: Work exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. Inf. Manag. 2013, 50, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Roziner, I.; Savaya, R. Professional identity, perceived job performance and sense of personal accomplishment among social workers in Israel: The overriding significance of the working alliance. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Cha, J.; Chang, K. Commitment to emotional display rules as a moderator between emotional labor and sense of accomplishment. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2019, 50, 220–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, H.; Reio, T.G. Personal Accomplishment, Mentoring, and Creative Self-Efficacy as Predictors of Creative Work Involvement: The Moderating Role of Positive and Negative Affect. J. Psychol. 2016, 151, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaboga, T.; Erdal, N.; Karaboga, H.A.; Tatoglu, E. Creativity as a mediator between personal accomplishment and task performance: A multigroup analysis based on gender during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 12517–12529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H.; Bennis, W.G. Personal and Organizational Change Through Group Methods: The Laboratory Approach; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, R.L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendoly, E. System Dynamics Understanding in Projects: Information Sharing, Psychological Safety, and Performance Effects. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 1352–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. Discov. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jie, Y.H.; Wang, L. Organizational fairness and employee work behavior: The mediating role of psychological security. J. Peking Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 51, 180–186. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Farh, C.I.; Farh, J.L. Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P. The construction and implementation of inclusive leadership—Based on the perspective of new generation employee management. China Hum. Resour. Dev. 2012, 31–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A.; Gittell, J.H. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemsen, E.; Roth, A.V.; Balasubramanian, S.; Anand, G. The influence of psychological safety and confidence in knowledge on employee knowledge sharing. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2009, 11, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraj, S.; Yan, A. Boundary work in knowledge teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashauer, S.A.; Macan, T. How can leaders foster team learning? Effects of leader-assigned mastery and performance goals and psychological safety. J. Psychol. 2013, 147, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A.; Dawson, M. Perceived supervisor and co-worker support for error management: Impact on perceived psychological safety and service recovery performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M.; Frese, M. Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yan, J. The impact of organizational trust atmosphere on task performance. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2007, 1111–1121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L. Perceived organizational support: A literature review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2019, 9, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwan, M.; Mulyani, S.R.; Ali, H. Improving employee performance through perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Sys. Rev. in Pharm. 2020, 11, 839–849. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Cummings, I.; Armeli, S.; Lynch, P. Perceived organizational support, discretionary treatment, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Fasolo, P.M.; Davis-LaMastro, V. Effects of perceived organizational support on employee diligence, innovation, and commitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 53, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, L.M.; Wayne, S.J. Commitment and employee behavior: Comparison of affective commitment and continuance commitment with perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organ, D.W. Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan, B.; Enders, J. Support from the top: Supervisors’ perceived organizational support as a moderator of leader-member exchange to satisfaction and performance relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Noreen, S. Perceived organizational support as a moderator of affective well-being and occupational stress. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2015, 9, 865–874. [Google Scholar]

- Youssef, C.M.; Luthans, F. Positive organizational behavior in the workplace: The impact of hope, optimism, and resilience. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.; Koyasu, M.; Oh, S.; Ogawa, A.; Short, B.; Huang, Z. Culture, executive function, and social understanding. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2009, 123, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| KMO and Bartlett | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMO | 0.929 | |||

| Bartlett | Chi-square | 1726.522 | ||

| df | 120 | |||

| p | 0.000 | |||

| Cronbach | ||||

| (CITC) | Deleted alpha coefficient | Cronbach’s α | ||

| Age | −0.034 | 0.947 | 0.939 | |

| Gender | −0.056 | 0.946 | ||

| My career conditions are excellent. | 0.701 | 0.935 | ||

| My organization strongly considers my goals. | 0.801 | 0.932 | ||

| My organization strongly considers my values. | 0.857 | 0.931 | ||

| I am satisfied with my career. | 0.607 | 0.937 | ||

| Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions. | 0.819 | 0.932 | ||

| In my work, leaders encourage me to propose new plans and ideas. | 0.810 | 0.932 | ||

| Leaders treat employees fairly. | 0.797 | 0.932 | ||

| When something goes wrong, I engage in self-reflection. | 0.468 | 0.939 | ||

| Leaders emphasize fairness and justice in team management. | 0.822 | 0.931 | ||

| I regularly align my personal goals with the organization’s objectives. | 0.619 | 0.937 | ||

| Leaders appreciate and support cross-departmental collaboration. | 0.796 | 0.933 | ||

| When employees make mistakes, leaders express emotional understanding and provide constructive feedback. | 0.798 | 0.932 | ||

| Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements. | 0.782 | 0.933 | ||

| In my work, leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts. | 0.839 | 0.931 | ||

| Cronbach’s α = 0.927 | ||||

| My career conditions are excellent. | leaders openly Recognize employees’ achievements. | In my work, leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts. | My career conditions are excellent. | ||

| Constant | 1.370 ** (4.740) | 0.288 (1.088) | 0.138 (0.581) | 1.282 ** (4.599) | |

| Leaders appreciate and support cross-departmental collaboration. | 0.258 * (2.581) | 0.584 ** (6.378) | 0.541 ** (6.604) | 0.023 (0.199) | |

| When employees make mistakes, leaders express their emotional understanding and provide constructive feedback. | 0.389 ** (4.630) | 0.345 ** (4.471) | 0.392 ** (5.679) | 0.235 * (2.568) | |

| Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements. | 0.199 * (2.037) | ||||

| In my work, leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts. | 0.218 * (1.997) | ||||

| Sample size | 138 | 138 | 138 | 138 | |

| R2 | 0.362 | 0.560 | 0.618 | 0.420 | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.352 | 0.553 | 0.613 | 0.403 | |

| F | F (2,135) = 38.283, p = 0.000 | F (2,135) = 85.769, p = 0.000 | F (2,135) = 109.364, p = 0.000 | F (4,133) = 24.089, p = 0.000 | |

| * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 ():t | |||||

| I regularly align my personal goals with the organization’s objectives. | Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions. | Leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts. | In my work, leaders encourage me to propose new plans and ideas. | I regularly align my personal goals with the organization’s objectives. | |

| Constant | 1.263 ** (4.251) | 0.602 * (2.447) | 0.146 (0.635) | 0.099 (0.440) | 1.095 ** (3.684) |

| Leaders appreciate and support cross-departmental collaboration. | 0.444 ** (4.052) | 0.447 ** (4.931) | 0.462 ** (5.442) | 0.637 ** (7.715) | 0.315 * (2.359) |

| Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements. | 0.197 * (2.181) | 0.395 ** (5.282) | 0.451 ** (6.452) | 0.313 ** (4.591) | 0.058 (0.546) |

| Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions. | 0.259 * (2.411) | ||||

| In my work, leaders actively seek my opinions and thoughts. | 0.137 (1.153) | ||||

| In my work, leaders encourage me to propose new plans and ideas. | −0.080 (−0.662) | ||||

| Sample size | 138 | 138 | 138 | 138 | 138 |

| R2 | 0.330 | 0.566 | 0.639 | 0.656 | 0.372 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.320 | 0.559 | 0.633 | 0.651 | 0.349 |

| F | F (2,135) = 33.233, p = 0.000 | F (2,135) = 87.862, p = 0.000 | F (2,135) = 119.273, p = 0.000 | F (2,135) = 128.950, p = 0.000 | F (5,132) = 15.668, p = 0.000 |

| * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 ():t | |||||

| In My Work, Leaders Actively Seek My Opinions and Thoughts. | When Something Goes Wrong, I Engagee in Self-Reflection. | I Regularly Align My Personal Goals with the Organization’s Objectives. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | ||||

| Constant | 0.626 | 0.302 | 2.074 | 0.040 * | 3.509 | 0.507 | 6.928 | 0.000 ** | 2.927 | 0.564 | 5.189 | 0.000 ** | |||

| Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions. | 0.639 | 0.064 | 10.010 | 0.000 ** | 0.139 | 0.143 | 0.969 | 0.334 | −0.071 | 0.159 | −0.447 | 0.655 | |||

| Leaders treat employees fairly. | −0.271 | 0.188 | −1.442 | 0.152 | −0.175 | 0.210 | −0.833 | 0.406 | |||||||

| Leaders recognize my efforts and contributions. × Leaders treat employees fairly. | 0.074 | 0.044 | 1.674 | 0.097 | 0.119 | 0.049 | 2.417 | 0.017 * | |||||||

| When something goes wrong, I engage in self-reflection. | −0.081 | 0.085 | −0.955 | 0.341 | |||||||||||

| I regularly align my personal goals with the organization’s objectives. | 0.239 | 0.072 | 3.328 | 0.001 ** | |||||||||||

| Sample size | 138 | 138 | 138 | ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.593 | 0.238 | 0.346 | ||||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.581 | 0.215 | 0.326 | ||||||||||||

| F | F (3,134) = 65.121, p = 0.000 | F (3,134) = 13.958, p = 0.000 | F (3,134) = 23.624, p = 0.000 | ||||||||||||

| * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 | |||||||||||||||

| Direct Effect | |||||||||||||||

| Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | ||||||||||

| 0.639 | 0.064 | 10.010 | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.765 | ||||||||||

| In My Work, Leaders Actively Seek My Opinions and Thoughts. | My Career Conditions Are Excellent. | I Am Satisfied with My Career. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | β | SE | t | p | |||

| Constant | 0.186 | 0.247 | 0.751 | 0.454 | 2.588 | 0.585 | 4.425 | 0.000 ** | 1.990 | 0.617 | 3.226 | 0.002 ** | ||

| Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements. | 0.577 | 0.063 | 9.180 | 0.000 ** | −0.091 | 0.170 | −0.536 | 0.593 | −0.069 | 0.180 | −0.382 | 0.703 | ||

| My organization strongly considers my goals. | −0.046 | 0.201 | −0.227 | 0.821 | 0.456 | 0.212 | 2.154 | 0.033 * | ||||||

| Leaders openly recognize employees’ achievements × My organization strongly considers my goals. | 0.118 | 0.050 | 2.367 | 0.019 * | 0.030 | 0.053 | 0.564 | 0.574 | ||||||

| My career conditions are excellent. | 0.130 | 0.085 | 1.534 | 0.128 | ||||||||||

| I am satisfied with my career. | 0.196 | 0.076 | 2.568 | 0.011 * | ||||||||||

| Sample size | 138 | 138 | 138 | |||||||||||

| R2 | 0.617 | 0.465 | 0.406 | |||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.605 | 0.448 | 0.388 | |||||||||||

| F | F (3,134) = 71.911, p = 0.000 | F (3,134) = 38.760, p = 0.000 | F (3,134) = 30.490, p = 0.000 | |||||||||||

| * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 | ||||||||||||||

| Direct Effect | ||||||||||||||

| Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |||||||||

| 0.577 | 0.063 | 9.180 | 0.000 | 0.454 | 0.701 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Gao, H. Moderated Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Innovation Behavior. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093962

Liu J, Liu X, Gao H. Moderated Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Innovation Behavior. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093962

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jialin, Xinyu Liu, and Hongbo Gao. 2025. "Moderated Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Innovation Behavior" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093962

APA StyleLiu, J., Liu, X., & Gao, H. (2025). Moderated Mediation Analysis of the Relationship Between Inclusive Leadership and Innovation Behavior. Sustainability, 17(9), 3962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093962