Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Global Literature Review: Concepts and Practices

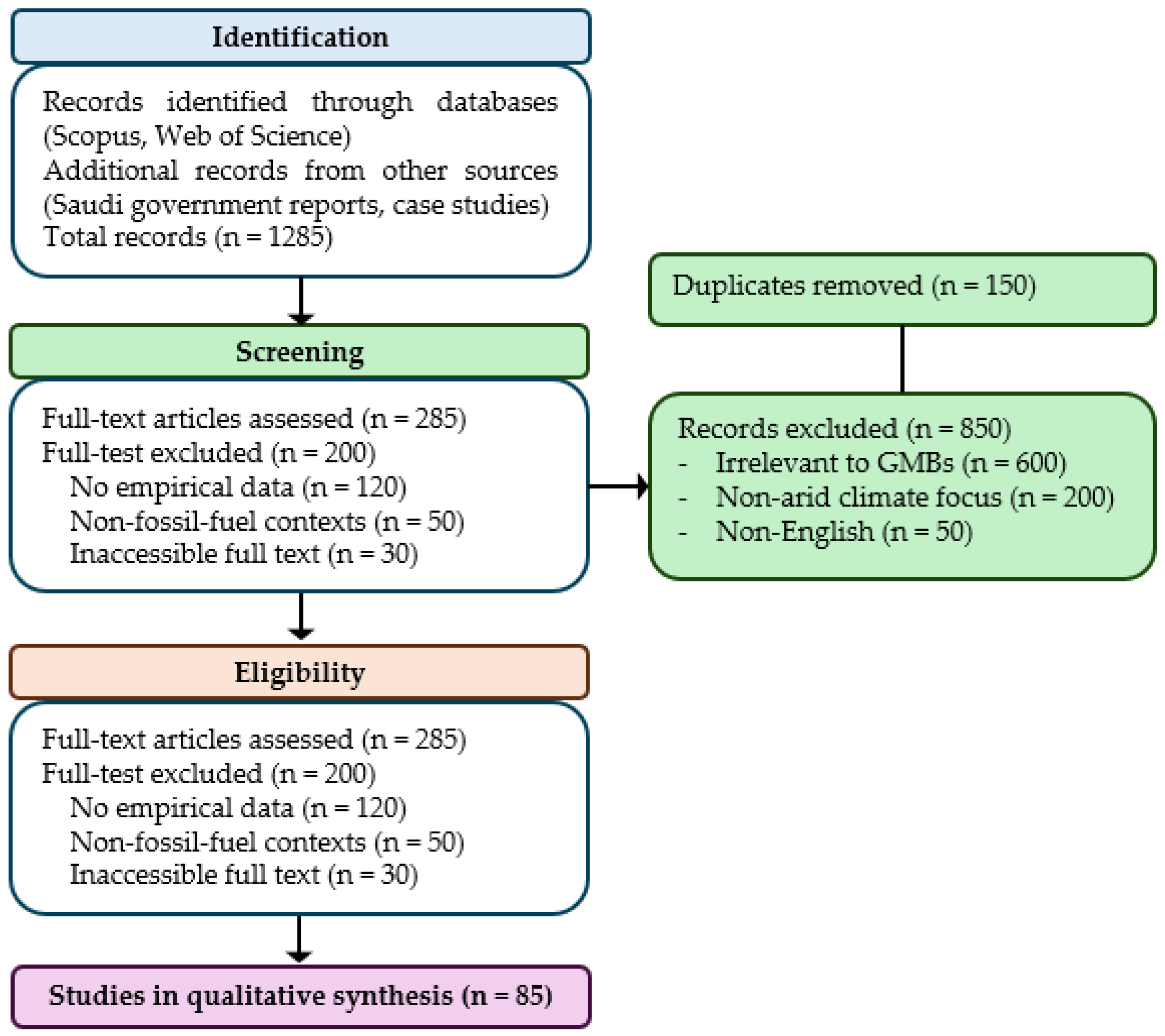

3. Materials and Methods

4. Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabia: Principles, Initiatives, and Policies

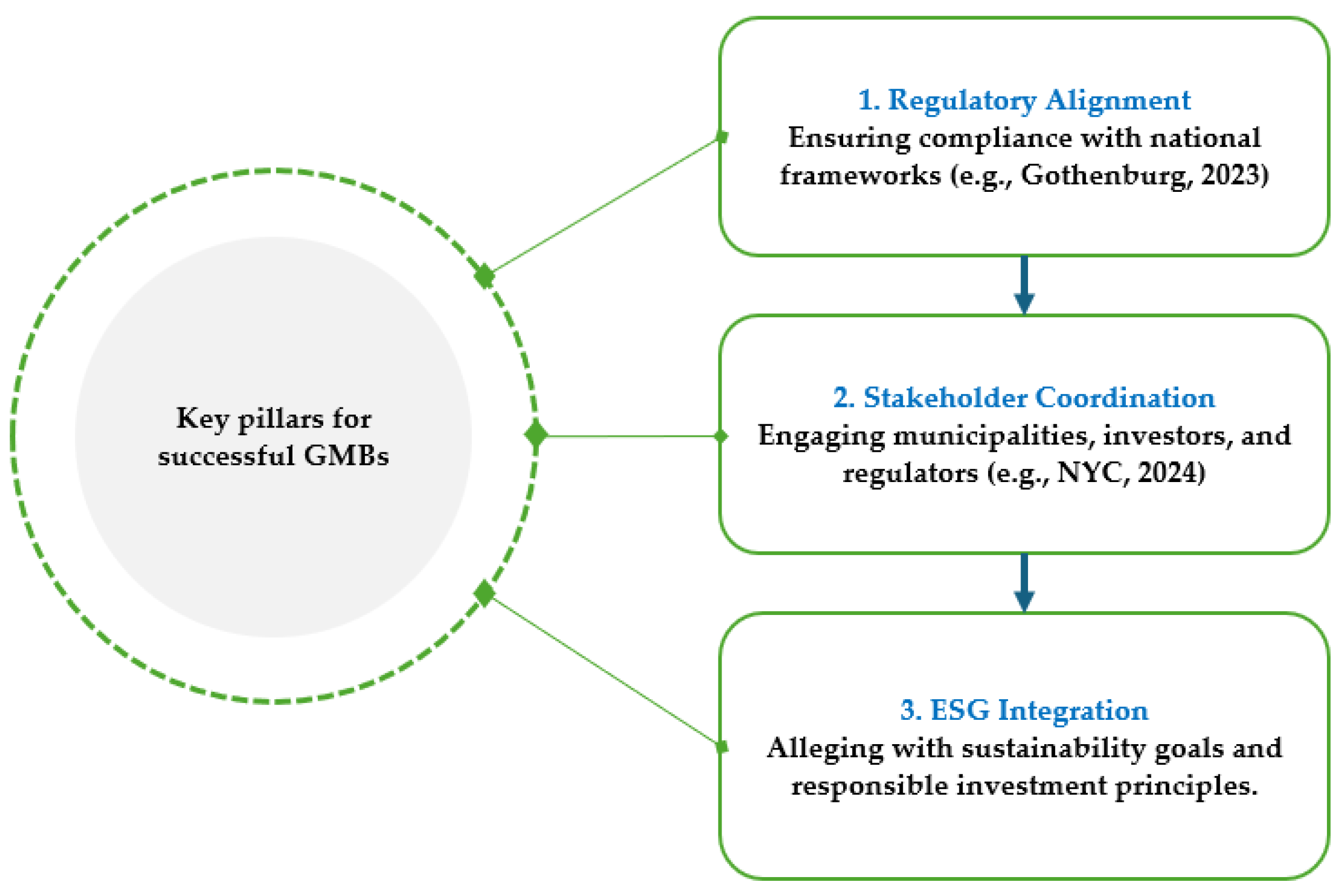

5. Discussion: GMB Adoption in Saudi Arabia

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs and Housing (MOMRA). National Urban Development Strategy; Saudi Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hathloul, S.; Mughal, M.A. Urban Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: Opportunities and Challenges. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2020, 146, 04020018. [Google Scholar]

- Matar, W. Energy efficiency in Saudi Arabia’s built environment: Progress and challenges. Energy Effic. 2023, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Fattah, S.M. Renewable energy integration in Saudi Arabia: A techno-economic analysis. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120–135. [Google Scholar]

- Lahn, G. Saudi Arabia’s Energy Transition: Balancing Oil and Climate; Chatham House Report: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Vision 2030. National Transformation Program: Sustainable Development Goals; Official Vision 2030 Document: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Municipal, Rural Affairs and Housing (MOMRA). Municipal Finance Reports (2023); Saudi Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Finance (MOF). Annual Budget Statements (2013–2023); Saudi Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). The Role of Green Bonds in Financing Climate-Resilient Cities; CBI Annual Report; Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). Global Green Bond Standards; CBI Official Report; Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI): London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Green Finance and Investment: Mobilizing Capital for Climate-Resilient Infrastructure; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Financing Climate-Resilient Cities: The Role of Green Bonds; OECD Urban Policy Review; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Barngetuny, J. Financing the Transition to Net-Zero in Kenya: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Stud. 2024, 14, 480–488. [Google Scholar]

- Alawadi, K.; Khanal, A.; Al-Saidi, M. Green finance in GCC urban governance: Challenges and opportunities. Energy Policy 2023, 178, 113567. [Google Scholar]

- New York State Comptroller. Reports: Annual Debt Reports Detail Bond Issuances for Environmental Projects; State Debt Reports; New York State Comptroller: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- City of Cape Town. The City’s 2018–2022 Drought Response Included Funding for Water Security. A ZAR 1 Billion Green Bond; Treasury Reports; City of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hertog, S. Energy transitions in rentier states: A Saudi case study. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 108, 103402. [Google Scholar]

- Amundi-IFC. Emerging Market Green Bonds: Trends and Opportunities; Amundi Institute Report; Amundi-IFC: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A.P.J. Globalization and Environmental Reform: The Ecological Modernization of the Global Economy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. The city as a hybrid: On nature, society, and cyborg urbanization. Capital. Nat. Social. 1996, 7, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Investment Fund (PIF). Saudi Arabia’s Inaugural Sovereign Green Bond Issuance: $3 Billion for Sustainable Projects. 2022. Available online: https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/news-and-insights/press-releases/2022/usd-3-billion-inaugural-bond (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Public Investment Fund (PIF). PIF Green Bond Impact Assessment 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.pif.gov.sa/-/media/project/pif-corporate/pif-corporate-site/our-financials/capital-markets-program/pdf/pif-green-bond-impact-assessment-2024.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Mehmood, U. Green finance and sustainable development goals: The role of Islamic finance. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). Saudi Green Initiative: Roadmap for Sustainability and Climate Action. 2021. Available online: https://www.sgi.gov.sa/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Saudi Green Initiative (SGI). Annual Sustainability Report; Saudi Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zweig, P. The Saudi Green Initiative: A Roadmap for Sustainable Development; Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Financing Sustainable Cities; OECD Urban Policy Review; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ICMA. Green Bond Principles; International Capital Market Association Report; ICMA: Zürich, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- BlackRock. Sustainable Investing: Reshaping the Financial Landscape; BlackRock Global Report; BlackRock: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Green Bonds for Sustainable Cities; World Bank Climate Finance Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Green Finance for Sustainable Urbanization; United Nations Report; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Gothenburg Green Bonds—Financing for Climate-Friendly Investment; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/financing-for-climate-friendly/gothenburg-green-bonds (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- City of Gothenburg. Green Bonds in Gothenburg; City of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, NE, USA, 2024; Available online: https://goteborg.se/wps/portal?uri=gbglnk%3A2019923102711631 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- New York City Office of the Mayor. Recovery for All of Us: Mayor de Blasio, Comptroller Stringer, and Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation Announce Successful Green Bond Issuance; New York City Office of the Mayor: New York, NY, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/694-21/recovery-all-us-mayor-de-blasio-comptroller-stringer-hudson-yards (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Office of the New York City Comptroller. The City of New York Announces Successful Sale of $1.1 Billion of General Obligation Bonds; Office of the New York City Comptroller: New York, NY, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/assets/investorrelations/downloads/pdf/pr/gopr-07-31-24.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- City of Cape Town. City of Cape Town Green Bond Framework. 2017. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/files/files/Cape%20Town%20Green%20Bond%20Framework.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- REGlobal. Green Bond Market in South Africa. 2022. Available online: https://reglobal.org/green-bond-market-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- ICMA. Sustainability Bond Guidelines; International Capital Market Association Report; ICMA: Zürich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. ESG Investing and Municipal Bond Markets; OECD Working Paper; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Policy Initiative. Aligning National Green Taxonomies with ESG Standards; CPI Report; Climate Policy Initiative: Rio, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Afripoli. Easing Africa’s Climate Crisis: Can Green Bonds Help Close the Climate Finance Gap? 2024. Available online: https://afripoli.org/easing-africas-climate-crisis-can-green-bonds-help-close-the-climate-finance-gap (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Green Bonds in Latin America; IDB Financial Insights Report; IDB: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, S. The Principles of Green Urbanism: Transforming the City for Sustainability; Earthscan Publications: Oxford, MS, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bulkeley, H.; McGuirk, P.M.; Dowling, R. Urban climate governance and green finance. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 1001–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, T.; Bauer, R.; Orlitzky, M. ESG and green bonds: A global review of standards and market practices. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2022, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Blue Horizon Energy. The Emergence of Municipal Green Bonds in South Arica. 2022. Available online: https://www.bluehorizon.energy/financing-climate-change-adaptation-the-emergence-of-municipal-green-bonds-in-south-africa/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Luomi, M. Gulf states’ climate change mitigation strategies: Beyond rentierism? Middle East Policy 2022, 29, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- DinarStandard. Islamic Finance and Sustainability: The Rise of Green Sukuk; DinarStandard Report; DinarStandard: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, A.M. Smart Cities as a Pathway to Sustainable Urbanism in the Arab World: A Case Analysis of Saudi Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Global Climate Action Highlights: Urban Transitions. 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Paulson Institute. Sustainable Urban Planning Principles. 2017. Available online: https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Sustainable-Urban-Planning_EN_vF.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Columbia|SIPA Center on Global Energy Policy. Saudi Arabia’s Renewable Energy Initiatives and Their Geopolitical Implications. 2023. Available online: https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/saudi-arabias-renewable-energy-initiatives-and-their-geopolitical-implications/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (MEWA). National Renewable Energy Program Overview; Saudi Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy, Industry, and Mineral Resources (MEIM). Saudi Arabia’s National Renewable Energy Program: Achieving 50% Renewable Energy by 2030; Government Publication: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- NEOM. NEOM Sustainability Framework; NEOM Official Report; NEOM: Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Business Group. Saudi Arabia’s Green Transition: From Oil to Renewables; OBG Report; Oxford Business Group: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, R. The Gulf Energy Transition: Opportunities and Challenges; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Reiche, D. Renewable energy policies in Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Gielen, D. Renewable energy prospects for the Gulf Cooperation Council. Renew. Energy 2023, 200, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (RCRC). Annual Report: Climate Change and Humanitarian Action. 2020. Available online: https://stories.climatecentre.org/annual-report-2020/index.html (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Saudi Building Code. Green Building Regulations; Government of Saudi Arabia: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC). Green Building Trends: USGBC Annual Report 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.usgbc.org/resources/usgbc-annual-report-2021 (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Ewis, H.F. The Role of Green Financing in Transforming Financial Institutions in Saudi Arabia: A Focus on ESG Innovations. Pakistan journal of life and social sciences 2025, 23, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M. Sustainable urban transitions in the Gulf: Challenges and opportunities. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112703. [Google Scholar]

| Feature | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Use of Proceeds | Funds must be allocated exclusively to green projects, such as renewable energy, sustainable transport, or climate adoption initiatives. | A city issues a GMB to finance a new solar farm, reducing reliance on fossil fuels. |

| Certification and Standards | Issuers must follow recognized frameworks such as the Green Bond Principles (GBP) by the ICMA or the Climate Bonds Standard (CBS) by the Climate Bonds Initiative. | A municipality follows the Green Bond Principles to certify its green bond for water conservation projects. |

| Transparency and Reporting | Regular disclosures ensure accountability, including updates on fund allocation and environmental impact assessments. | A city government publishes an annual report showing how bond proceeds were used for energy-efficient building upgrades. |

| Investor Appeal | Attracts ESG-focused investors, contributing to sustainable finance trends and boosting credibility in financial markets. | Institutional investors, such as pension funds, purchase green bonds to align with their ESG investment strategies. |

| Category | Key Aspect | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits | Climate Action and Environmental Impact | Funds green projects such as renewable energy, public transit, and climate-resilient infrastructure. Reduces carbon footprint and aligns with global climate goals (e.g., Paris Agreement) [10,30]. |

| Economic Advantages | Lower borrowing costs attract ESG investors, leading to competitive interest rates. Energy-efficient projects reduce operational costs. Creates jobs in green sectors (e.g., solar installation, urban forestry) [15]. | |

| Investor Appeal | Appeals to institutional investors (e.g., BlackRock, pension funds) prioritizing ESG factors. Expands a municipality’s investor base to include global green finance markets [29]. | |

| Enhanced Transparency and Accountability | Mandatory reporting ensures regular updates on project progress and environmental impact. Certification standards (e.g., Green Bond Principles) build credibility [28]. | |

| Social Equity | Supports underserved communities with projects such as clean water access and flood defenses. Improves overall quality of life through cleaner air, better public transport, and green spaces [42]. | |

| Resilience Building | Helps mitigate climate risks through projects such as coastal defenses and drought-resistant infrastructure [37]. | |

| Barriers | High Upfront Costs | Green infrastructure projects (e.g., smart grids) require significant initial investment. Municipal budgets face competing priorities such as healthcare and education [15]. |

| Lack of Expertise and Capacity | Smaller cities may lack technical knowledge in green finance or project design. Certification processes (e.g., Climate Bonds Standard) can be complex and resource-intensive [28]. | |

| Regulatory and Political Challenges | Fragmented policies make bond issuance difficult. Political instability may disrupt long-term sustainability projects [10]. | |

| Market Risks | Emerging markets face higher borrowing costs due to currency/credit risks. Greenwashing concerns create skepticism about environmental impact [37]. | |

| Limited Investor Awareness | Some investors are unfamiliar with GMBs, particularly in developing markets. Smaller bond issuances may struggle to attract institutional investors [42]. | |

| Reporting Burden | Ongoing compliance requires dedicated resources for impact reporting, data collection, and auditing [28]. |

| Framework | Focus | Unique Saudi Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| World Bank Green Cities | Broad urban sustainability | Integrates oil price volatility and arid-climate resilience [30]. |

| OECD Green Finance | Policy coherence | Shariah-compliant mechanisms [21,22,26]. |

| This Study | Fossil-fuel contexts | Blends ESG metrics with Islamic finance [23,48,49]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhowaish, A.K. Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093950

Alhowaish AK. Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2025; 17(9):3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093950

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhowaish, Abdulkarim K. 2025. "Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 17, no. 9: 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093950

APA StyleAlhowaish, A. K. (2025). Green Municipal Bonds and Sustainable Urbanism in Saudi Arabian Cities: Toward a Conceptual Framework. Sustainability, 17(9), 3950. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17093950