Abstract

This study examines Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement by comparing its climate policy framework with those of Germany and Spain—two EU countries with absolute, legally binding emission reduction targets. Despite ratifying the Paris Agreement in 2021 and declaring a net-zero target for 2053, Türkiye’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) lacks absolute reduction commitments and a comprehensive Climate Act. This gap is particularly critical given the EU’s implementation of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which links climate action to trade competitiveness. Using a comparative policy analysis approach, this study evaluates official emission data, legal documents, and EU climate progress reports to assess the coherence of Türkiye’s climate strategy. The findings indicated that Türkiye’s emissions continue to rise in the presence of fossil fuel domination and the absence of binding targets. Conversely, Germany and Spain have reduced emissions through robust legislation, functioning Emissions Trading Systems, and long-term investment in renewables. This study offers policy recommendations tailored to Türkiye’s context, including the adoption of absolute and binding targets, acceleration of renewable energy—especially solar—and the promotion of community-based energy models, inspired by Spain’s approach. Additionally, mechanisms to balance energy security, local acceptance, and decarbonization are discussed, drawing from Germany’s phased fossil fuel exit. The results indicate that Türkiye’s ability to align with EU climate targets and the Paris Agreement without compromising its development priorities or energy supply security can only be achieved with a realistic roadmap and specific reforms.

1. Introduction

The Paris Agreement aims to address climate change (Art. 2/1) and promote a development model based on low greenhouse gas emissions (Art. 2/1-b) [1,2]. While the Agreement comprises a combination of non-binding, flexible, and stringent provisions [3], it establishes a framework that allows parties to achieve their emission reduction targets in a manner adaptable to their national circumstances. Thus, the core aspect of the Agreement lies in its provision of a “flexible framework” [4]. Despite this structure, Türkiye ratified the Paris Agreement in 2021, expressing certain reservations. Accordingly, Türkiye has declared that it will implement the Agreement as follows:

- Based on the principles of equity, common but differentiated responsibilities, and respective capabilities;

- Under its status as a developing country;

- Within the framework of the commitments outlined in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC);

- Provided that the Agreement and its mechanisms do not adversely impact its economic and social development [5].

However, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) [6] regulations, which can be referred to as a “green customs duty” implemented by the EU, Türkiye’s largest export market with a share of 56.9% [7], constitute a foreign trade mechanism that narrows the flexible framework introduced by the Paris Agreement and transforms emission reduction from a voluntary effort based solely on the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) into a mandatory obligation. As a global leader in greenhouse gas emission reduction and compliance with the Paris Agreement, the EU thus compels exporting countries, such as Türkiye, to undergo a similar transformation. Countries that do not tax carbon and fail to transition toward low-emission investments quickly enough face the risk of losing their price competitiveness in exports to the EU due to the CBAM [8].

The loss of strength and competitive advantage in exports to the EU is not a desirable outcome for Türkiye. Therefore, under current conditions, it has become imperative for Türkiye to swiftly align with EU legislation and practices. This includes addressing deficiencies related to the enactment of framework laws by the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye (GNAT), updating policy documents with more ambitious targets, and more effectively directing incentive mechanisms toward investments that support emission reduction [9].

Türkiye can benefit from the legislation and practices of many countries worldwide in areas such as compliance with the Paris Agreement, the climate law framework, the formulation of policy documents, and the adaptation of incentive mechanisms to evolving conditions. However, considering that its largest export market is the EU, this study identifies two EU member states, Germany and Spain, as benchmark countries. Specifically, Germany, the EU’s leading economy, has a total population (83,280,000) similar to that of Türkiye (85,325,965) [10]. Compared to Türkiye, Germany has a developed climate policy and law [11]. Additionally, Türkiye has historically drawn upon German laws and its legal system when enacting fundamental legislation, and these factors have been influential in selecting it as a benchmark country.

Like Türkiye, Spain, whose southern part is located in the Mediterranean climate zone, has a high number of sunny days. In recent years, it has accelerated its renewable energy investments and significantly increased its installed capacity, particularly in solar energy [12]. When examining Türkiye’s National Energy Plan (NEP) and the installed capacity targets by energy source, solar energy is projected to rank first with 52.9 GW by 2035 [13]. Considering these factors, Spain has been evaluated as a suitable benchmark for Türkiye in terms of transitioning to renewable energy, particularly solar energy.

Considering that Türkiye ratified the Paris Agreement under the status of a “developing country” [5], it is possible to identify several developing countries that could serve as examples in the compliance process. However, the strong trade ties between Türkiye and the EU [7] and the fact that the EU’s CBAM compels Türkiye to undergo a transformation similar to that of the EU have been the key factors in selecting the two EU members.

With the ratification of the Agreement, Türkiye has announced its 2053 climate neutrality target [14]. In line with this target, it has envisaged developing strategies focused on increasing the use of renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and adopting policies for low-carbon production processes in the industry [15].

This study analyzes Türkiye’s current position regarding the Paris Agreement, which seeks to mitigate global carbon emissions. It explores the challenges faced in the compliance process and evaluates potential strategies to overcome these challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, Türkiye’s Paris Agreement compliance is evaluated by a comparative analysis method. This study examines Türkiye’s climate policies and framework climate legislation (if enacted) in comparison with those of two EU member states, Germany and Spain. The analysis focuses on greenhouse gas emission trends, renewable energy policies—particularly those related to solar energy—and the regulatory framework governing climate action.

2.1. Methodology

Both qualitative and quantitative analysis methods are used in this study. Quantitative analysis relies on the data between 1979 and 2023, while qualitative analysis covers between 1979 and 2025, depending on data availability.

- Comparative Legal Analysis: The framework climate legislation of Germany, Spain, and Türkiye (where applicable) are examined.

- Statistical Trend Analysis: Changes in per capita emissions and installed renewable energy (solar) capacity trends across selected countries are examined.

- Policy Assessment: Türkiye’s climate policies and emission trends are analyzed in relation to their alignment with the objectives of the Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal.

2.2. Criteria for Selecting Benchmark Countries

Germany and Spain, the two leading EU countries, have been selected for a comparative analysis for the assessment of Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement, based on the key criteria outlined in Table 1. While it is theoretically possible to include additional EU countries, a limited but carefully selected number of representative cases was preferred to enable a focused and in-depth comparative analysis. The comparative evaluation of Germany, Spain, and Türkiye reveals both shared characteristics and significant differences, supporting the appropriateness of Germany and Spain as benchmark countries. The choice of EU member states is particularly grounded on Türkiye’s strong economic ties with the European Union—especially with Germany, which remains Türkiye’s largest export partner—as well as its need to harmonize national policies with EU regulations under the European Green Deal and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) [6]. Germany, as the EU’s largest economy [16], represents a prominent example of advanced climate governance, with legally binding emission reduction targets and an established climate policy framework. Spain, on the other hand, offers geographic and climatic proximity to Türkiye, particularly due to their shared Mediterranean climate, and stands out for its notable progress in solar energy development, especially between 2018 and 2023. The comparison is strengthened further with Türkiye’s own National Energy Plan (NEP) [13], which projects that solar power will become the leading source of installed energy capacity by 2035. In parallel, as a developing country increasingly integrated into the EU market, Türkiye faces mounting pressure to accelerate its green transition in line with CBAM-driven regulatory expectations [6]. Other EU countries were not included, as they did not offer the same level of regulatory impact, economic relevance, or contextual similarity needed to support the analytical objectives of this study within its defined scope.

Table 1.

Criteria for selecting benchmark countries. The symbols indicate that the elements are ✔: present and ✘: not present.

2.3. Data Sources

The data utilized in this study were compiled from a range of authoritative national and international sources to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness. National-level data were primarily obtained from official climate and environmental reports published by the Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT) and the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change (MEUCC), along with the European Commission’s Türkiye Report for 2024 [23]. International data sets and comparative indicators were sourced from globally recognized institutions, including the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) [35], the World Bank (WB) [10,33,36,37,38], and the Global Carbon Budget (GCB) [39,40]. In addition, legal and policy documents—such as Germany’s and Spain’s national emission laws and relevant European Union climate legislation—were analyzed to support the comparative legal framework of this study.

2.4. Analysis Process

The data were analyzed using statistical comparisons, trend analyses, and policy compliance assessments. This study’s framework is as follows:

- Data Currency: Some data are restricted to specific years. In the scope of this comparative analysis, countries that share certain structural similarities with Türkiye—such as economic scale, energy transition processes, emission trends, and trade relations—were initially considered. Germany, Spain, China, and Mexico could all be seen as potential benchmark countries in this context. However, this study limits the comparative assessment to Germany and Spain, both members of the European Union (EU), due to Türkiye’s direct economic, legal, and political alignment with the EU. In particular, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) represents a regulatory framework that directly affects Türkiye’s climate and trade policy orientation. In contrast, Mexico’s primary export partner is the United States [36], which results in substantially different legal and policy dynamics. China, however, is a scale economy and has a population of 1.41 billion as of 2023 [37]. While it is a global leader in installed renewable energy capacity, it is a global leader in installed renewable energy capacity, however in annual CO2 emissions as well [41]. Furthermore, China does not exert regulatory pressure on Türkiye comparable to the EU’s CBAM [6]. For these reasons, China and Mexico were excluded from the comparative framework, and Germany and Spain were selected as reference countries with comparable legal structures, trade orientation, and climate policy instruments.

- Policy Changes: Recent legislative changes have been considered during the analysis process. Within the framework of the specified methodology, strategic recommendations have been developed for Türkiye’s compliance process under the Paris Agreement by drawing insights from the successful practices of Germany and Spain.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Türkiye’s Current Status Under the Paris Agreement

Türkiye’s designation as a “developing country” under the Paris Agreement affords it a degree of procedural flexibility, allowing for nationally determined mitigation pathways without the imposition of absolute emission reduction obligations. This status provides a critical advantage in terms of policy autonomy, enabling Türkiye to frame its climate commitments in alignment with national development priorities and economic capabilities. Furthermore, it strengthens Türkiye’s position in international climate negotiations by preserving its right to access climate finance and capacity-building support mechanisms.

However, this formal flexibility is increasingly constrained by Türkiye’s deep economic integration with the European Union, particularly in the context of the European Green Deal and the CBAM. While Türkiye does not bear legally binding emission reduction targets under the Paris framework, its export-oriented economy is de facto subject to the EU’s regulatory environment, which mandates rigorous carbon accountability. This dynamic places Türkiye in a hybrid position—retaining the nominal privileges of a developing country, yet simultaneously compelled to adhere to the behavioral expectations of developed economies.

From this perspective, the dual structure presents both strategic opportunities and critical challenges. On the one hand, Türkiye can leverage its developing country status to preserve developmental space and negotiate favorable conditions within global climate governance. On the other hand, the urgency to align with EU sustainability standards necessitates accelerated structural reforms, potentially generating socio-economic pressures, especially in carbon-intensive sectors. Thus, Türkiye must navigate a complex policy landscape wherein it is expected to balance its sovereign development trajectory with the imperatives of external regulatory convergence.

3.1.1. Türkiye’s Accession Process and Commitments

The Paris Agreement was signed by Türkiye in 2015; however, its ratification process was not finalized until 2021. One of the main factors contributing to this delay was Türkiye’s classification as a “developed country” under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which restricted its access to financial mechanisms [42]. Limitations related to climate financing and technology transfer were among the key challenges that delayed the ratification process.

Together with the ratification of the Agreement, Türkiye, compared to the reference scenario, committed to reducing its emissions by 21% by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2053 [43]. This target was later updated [15]. To reach the said targets, first of all, the energy sector, reliant on fossil fuels, must move towards renewable energy sources, cost-effective solutions to reduce emissions in industrial enterprises and transportation sectors must be adopted, and energy efficiency in buildings needs to be improved. However, the implementation of the commitments is closely linked to the availability of infrastructure and sources.

The EU’s new policy for economic development, the European Green Deal, on the other hand, paved the way for Türkiye’s decision to ratify the Agreement. The need to comply with EU regulations such as CBAM [6] has driven Türkiye to initiate transformations in key sectors such as energy, industry, and agriculture. Türkiye’s Customs Union with the EU made the adoption of the European Green Deal policies a necessity, ultimately leading to the country’s ratification of the Agreement [11]. In this context, Türkiye’s commitments under the Paris Agreement are shaped not only by environmental obligations but also by economic and social interests [15]. Indeed, the fact that the Agreement was ratified with certain reservations confirms this aspect [5].

3.1.2. Türkiye’s Carbon Emissions, Updated Nationally Determined Contribution, 2024 EU Report, and Transition to Renewable Energy

To better understand Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement and its carbon emissions in light of its 2053 climate neutrality target, it is essential to compare its emissions with those of other countries or regions. The EU plays a regional and global leadership role in Paris Agreement compliance, climate law, and the transition to a green economy [44]. Since the developments in the EU have a strong impact on Türkiye, a comparison of the changes in their per capita emissions can provide valuable insights. Such comparison helps us assess whether Türkiye is progressing in the same direction as the EU in its transition to a low-emission economy and the extent of its alignment with the EU policies. Figure 1 clearly illustrates this situation. While the EU is observed to be following a strong emission reduction trend, Türkiye has not aligned with this trajectory and appears to be following a significantly different path from the EU.

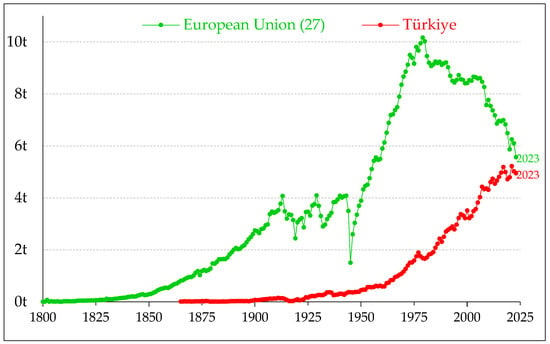

Figure 1.

Per capita carbon emissions: EU and Türkiye [39].

Indeed, Figure 1 shows that the EU, which began a gradual reduction in per capita carbon emissions in 1980, accelerated this process after 2006–2007 and has maintained the same trend following entry into the force of the Paris Agreement. The same years, however (early 1980s), represent a period for Türkiye when its emissions began to rise rapidly. The data in Figure 1 clearly indicate that Türkiye has continued this trend to the present day, with emissions still on an upward trajectory. This situation is neither a sustainable path for Türkiye nor aligned with the transition to a low-carbon economy [45].

When examining sources of Türkiye’s emissions, it becomes clear that the largest share originates from energy production. Figure 2 presents data that clearly illustrate this situation. The energy sector plays a decisive role in total emissions through fossil fuel consumption and electricity generation [46]. Therefore, the transition in the Turkish energy sector towards renewables is at the core of the country’s transition to a low-carbon economy.

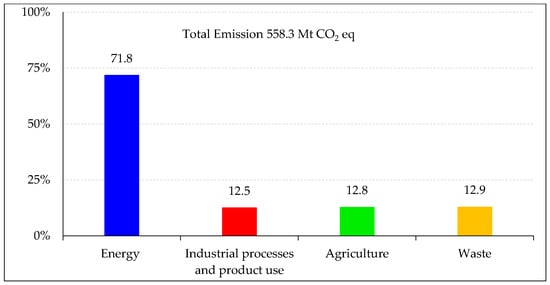

Figure 2.

Greenhouse gas emission shares by sector in Türkiye, 2022 [47].

Türkiye’s total emissions amounted to 558.3 Mt CO2 equivalent in 2022, based on the data in Figure 2. Of this total, 71.8% originated from the energy sector, while agriculture accounted for 12.8%, industrial processes and product use for 12.5%, and waste for 2.9%. The figures here clearly indicate that a significant portion of Türkiye’s emissions are generated by the energy sector. It is, therefore clear that this sector must be prioritized in reducing the emissions and speeding up the transition towards renewable energy [48].

Türkiye is currently undergoing a transformation that prioritizes the reduction in emissions in the energy sector. This transition has gained momentum in line with the commitments set under the Paris Agreement and the 2053 net-zero carbon target [35]. However, achieving these targets requires significant steps to be taken in energy production and the transition to renewable energy [13].

On the other hand, agriculture and industry are also significant emission sources in Türkiye (Figure 2). Among these, priority should be given to export-oriented sectors subject to the EU CBAM regulation, particularly the iron and steel industry [49].

In its updated NDC under the Agreement, which was submitted in 2022, Türkiye targeted a 41% reduction in emissions by 2030 compared to the Business as Usual (BAU) scenario. This target aims to reduce projected emissions from 1215 Mt CO2 equivalent under the BAU scenario to 695 Mt CO2 equivalent [15]. The NDC integrates both mitigation and adaptation measures, encompassing the entire economy to implement comprehensive climate action. Emissions are estimated to peak in 2038 and the climate neutrality target is expected to be achieved by 2053. The first period of implementation is between 1 January 2022 and 31 December 2030. The 2030 targets are defined within the BAU scenario as a reduction from projected increases rather than an absolute reduction in emissions [50].

However, the EU Türkiye 2024 Report states that Türkiye’s overall emission reduction targets are insufficient [51]. The report evaluates this situation as an indication that Türkiye’s updated NDC does not incorporate a science-based level of emission reduction, particularly in relation to short- and medium-term commitments. Also, it is recommended that a new NDC—one that establishes absolute reduction targets rather than reductions from projected increases—be prepared and submitted prior to the 30th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC, scheduled for November 2025 [23,52].

Additionally, the report notes that, as of its publication date (30 October 2024), neither a climate law supporting Türkiye’s 2053 climate neutrality target nor a domestic Emissions Trading System (ETS) has been enacted. The report also asserts that a long-term strategy for low-emission development has not yet been adopted under the Agreement. Moreover, it recommends aligning with the major updates in climate policies introduced through the EU’s comprehensive climate and energy legislative package, Fit for 55, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 [23].

In its updated NDC, Türkiye emphasizes that it is a developing country with ambitious climate change targets [53] and that further investment is needed for the transition to a green economy. It also states that, in line with Article 9 of the Paris Agreement [1], achieving a just transition toward the net-zero target requires the provision and mobilization of climate finance, considering Türkiye’s developing country status. The NDC further highlights that the implementation of its commitments heavily depends on access to new and additional international financial resources and that an increase in climate finance would accelerate climate actions, enabling the enhancement of contributions. The updated NDC also states that Türkiye remains unable to benefit from the Green Climate Fund, the largest climate fund under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement [15].

On the other hand, it is stated that the Draft Climate Law is under review by the GNAT [15]. Additionally, Türkiye aims to establish an ETS aligned with the EU, which will operate based on the “cap-and-trade” principle and cover emission-intensive sectors. The system is planned as a key mitigation instrument for the industrial and energy sectors, ensuring that emissions remain under control through an emissions cap, while reductions are achieved in the most cost-effective areas [54].

The Climate Law and the domestic ETS are key instruments that will enhance Türkiye’s compliance with both the Paris Agreement and the regulations under the European Green Deal through emission reductions. Preparation of the domestic ETS and its temporary implementation led by the Directorate of Climate Change (DCC) have reached their final stage. The draft preparations for the ETS and pilot implementation have been completed. Following the enactment of the Climate Law, a regulation will be issued to define the scope of the ETS, allocation rules, and key dates [55].

Preparations for a domestic ETS in Türkiye essentially began in 2015 with the practice of the Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification System [56]. Facilities exceeding a certain threshold (>100 kilotons of CO2 equivalent—ktCO2eq) in specific sectors, such as electricity, refineries, basic metals, non-metallic minerals, paper, and chemicals, are included within its scope. The ETS is expected to become operational in 2025. However, the ETS should not be regarded as the sole instrument to move towards a low-carbon economy. Existing and new regulations can strengthen carbon markets, align with incentives, or, in some cases, reduce the effectiveness of these incentives. Moreover, fossil fuel subsidies and tax advantages provided to certain sectors may limit the impact of the ETS [56].

In order to prevent and reduce emissions and waste generation at their source—particularly in industrial facilities operating in sectors such as energy, metal production and processing, the mineral industry (including cement production), the chemical industry, and waste management—and to mitigate air, water, soil, noise, and odor pollution, as well as to promote resource efficiency, green transformation in industry, circular economy, and decarbonization, the Regulation on the Management of Industrial Emissions was published in the Official Gazette on 14 January 2025, and entered into force (Art. 1). The regulation imposes an obligation on certain industrial facilities to obtain a Green Transformation in Industry Certificate within a specified period (Provisional Article 1) [57].

Another critical side of the process is to make sure that that energy is sourced from renewable resources. Indeed, the Medium-Term Program (2023) states that projects developed under the Renewable Energy Resource Area model will continue to include requirements for the use of domestically produced components [54].

According to 2020 data, fossil fuels accounted for 83.3% of Türkiye’s primary energy consumption [13]. Emissions are projected to peak in 2038 [35]. By 2053, the share of fossil fuels in total energy consumption is planned to be reduced to 20.8% [13]. In Türkiye’s coal phase-out process, concerns related to energy supply security and economic development remain key determining factors [58].

Ultimately, it can be stated that for Türkiye to achieve absolute emission reduction through the transition to renewable energy and enhance its compliance with the Paris Agreement, it is necessary to continue developing its legal, economic, and technical infrastructure, accelerate the process, and set more ambitious targets. Achieving the goals set under the Paris Agreement will only be possible through solid reforms in these areas.

3.1.3. Deficiencies and Challenges in the Compliance Process

The energy sector was responsible for the majority of Türkiye’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, contributing 71.8% to the national total—highlighting the sector’s central role in shaping the country’s emission trajectory. This high dependency highlights the need for a fundamental transformation of the energy system as a core component of national decarbonization efforts [47]. In this context, Türkiye faces the dual challenge of transforming its entire economy around the principle of sustainability to strengthen and accelerate its compliance with the Paris Agreement—ensuring that its competitive position in exports to the EU is not weakened—while also maintaining the need to accelerate its economic growth. Balancing these objectives represents the most significant difficulty [59].

In 2023, Türkiye’s annual per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) stood at USD 13,105.7 [38], placing it behind certain developed and developing countries. Türkiye aims to accelerate its development in social and economic fields such as education and employment. Additionally, per capita greenhouse gas emissions in Türkiye were 5 tons of CO2 equivalent in 2023, remaining below the average of developed countries [39,40]. Despite these challenges, the updated NDC states that Türkiye has adopted the most ambitious emission reduction targets possible within its national circumstances [15].

However, the efforts to accelerate economic growth, along with concerns related to energy security and economic stability, make it difficult to reduce the share of coal in Türkiye’s national energy mix, creating a limiting effect on the transition to renewable energy [13]. State subsidies for fossil fuels in Türkiye constitute a significant political economy constraint on the transition to renewable energy [60], and according to [61], strategies to increase renewable energy investment in Türkiye are not compatible with the country’s current political economy structure and growth model, as its development model is speculation-driven and shaped by short-term approaches. Indeed, the Twelfth Development Plan (2024–2028) states that domestic coal will continue to be used, with environmental impacts considered to the greatest extent possible, as part of Türkiye’s strategy to ensure energy supply security [62].

The 2024 EU Türkiye Report [23] suggests that Türkiye should complete its alignment with the EU acquis regarding climate action, particularly focusing on emission trading, and recommends the reduction in emissions and key emission sources (such as coal and other fossil fuels) through the Emissions Trading System (ETS), a market-based mechanism [23].

Türkiye’s efforts to establish a domestic ETS were hindered for a certain period due to some gaps in the legal framework [63]. However, the Climate Law Proposal (CLP) was submitted to the GNAT in February 2025. Under this law, the establishment of the ETS and the preparation of national allocation plans are envisaged. Accordingly, the pilot ETS period is set to begin in 2025 and is planned to last for a minimum of two years. During this period, certain facilities may be granted free allocations [26].

On the other hand, deficiencies in renewable energy infrastructure create a significant barrier to Türkiye’s ability to meet its emission reduction targets. Türkiye’s NEP [13] projects that the share of the installed renewable energy sources capacity will increase to 64.7% until 2035. However, limitations such as storage technologies and insufficient local production capacities are affecting the feasibility of achieving the above-mentioned goals [13].

The updated NDC notes that Türkiye requires more investment for the transition to a green economy and that it is expected that climate finance will be provided and mobilized in line with its developing country status. This point must be emphasized, as it highlights that the issue of Türkiye’s access to climate finance, due to its developing country status, stands out as one of the key challenges faced [13,64].

In conclusion, Türkiye faces the fundamental challenge of maintaining its competitive position in exports to the EU while rapidly transforming its entire economy in line with the Paris Agreement and sustainability principles, using cost-effective financing [65]. On the other hand, this transformation must be achieved without hindering development [5] or jeopardizing energy supply security [13].

3.2. Türkiye’s Targets Under the Paris Agreement

Türkiye’s targets under the Paris Agreement play a critical role in shaping sustainability policies aligned with national development priorities, as well as in developing a climate strategy that is integrated with international obligations. In this context, a detailed assessment is required regarding the content and adequacy of Türkiye’s declared targets, along with strategic policy solutions and benchmark country practices that could strengthen their implementability.

3.2.1. Türkiye’s Targets

According to Türkiye’s updated NDC, the goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 41% by 2030, compared to the reference scenario, using 2012 as the base year. Furthermore, emissions are expected to peak by 2038, and Türkiye aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2053 [15].

In pursuit of this target, the Climate Law is planned to be enacted [15], and preparations for its implementation are nearing completion. Additionally, regulations related to ETS and carbon credits are expected to be introduced [66], and the CLP was submitted to the GNAT in February 2025 [26].

Increasing investments in renewable energy in the energy sector and enhancing energy efficiency in the industrial and transportation sectors are also among the primary targets. Preparations are underway for the national green taxonomy, which will facilitate the direction of financial flows toward green investments [15]. Indeed, the DCC has published the “Türkiye Green Taxonomy Regulation Draft” [67]. The purpose of the regulation is to establish the principles and procedures for Türkiye’s Green Taxonomy, which aims to support economic activities aligned with sustainable development goals, promote the flow of financing toward sustainable investments, and prevent greenwashing in the market (Art. 1).

In recent years, investments at an important scale have been made in renewable energy to increase their share in the energy sector in Türkiye. For example, a solar power plant located in Konya Province, Turkey, is the Kalyon Karapınar Solar Power Plant. It has 1350 MW installed capacity and covers 20 million square meters. It consists of approximately 3.5 million solar panels. The investor describes it as the largest solar power plant in Europe due to its construction at a single location by a single investor and its operation by the same firm [68]. This example clearly demonstrates that Türkiye’s technical and administrative capacity should not be underestimated.

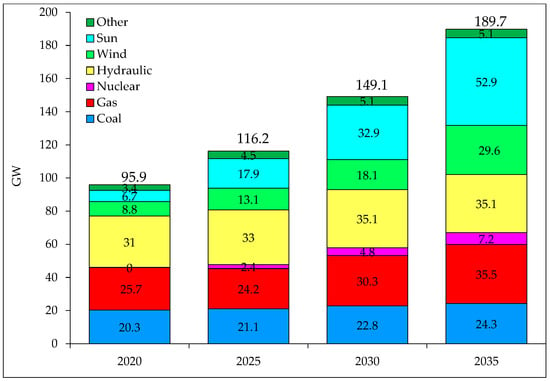

As stated above, the NEP of Türkiye [13] aims for 64.7% of the total electricity installed capacity to be resourced from renewable energy by 2035. In line with this, the data shared in Figure 3 show that the capacity of solar energy is planned to reach 52.9 GW, while wind energy is expected to reach 29.6 GW [13].

Figure 3.

Installed capacity by energy source in Türkiye [13].

Figure 3 reflects the distribution of Türkiye’s installed capacity for electricity generation by energy source from 2020 to 2035. Each energy source is shown in gigawatts (GWs) for specific periods. The total installed capacity is expected to reach 116.2 GW in 2025 and 189.7 GW by 2025 [13]. This represents an approximate 63% increase over the next 10 years. When looking at the increases by energy source, solar energy shows the most significant growth. Solar capacity is planned to rise 52.9 GW by 2035 from its projected level of 17.9 GW in 2025, which is expected to rise to 52.9 GW by 2035. This indicates a target increase of about 195% in installed solar capacity from 2025 to 2035, highlighting the leading role of solar energy in the country’s renewable energy goals [13].

During the same period, a significant increase in installed capacity for wind energy is also targeted (approximately 125%) (Figure 3). When comparing the installed capacity increase for solar and wind energy for the 2035 targets, it is evident that Türkiye aims to increase its solar capacity more significantly than its wind capacity. It is understood that hydropower plants will maintain their position as a long-term source and nuclear energy is also included in the plans. The coal capacity, which is at 21.1 GW level in 2025, is projected to slightly rise to 24.3 GW by 2035 (Figure 3). As a result, it can be anticipated that, in line with Türkiye’s 2035 targets, the share of renewable energy sources (especially solar energy) in the total installed capacity will significantly increase.

3.2.2. Adequacy of Current Targets

The goals of the Paris Agreement require the gradual reduction in fossil fuels (such as oil, coal, etc.) and a transition to renewable energy sources [69]. Also, Türkiye’s largest export market, the EU, has followed a strategy aimed at gradually reducing greenhouse gas emissions since the early 1980s (Figure 1).

The Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal have strengthened this trend. In the 1980s and 1990s, the EU focused on the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital, and today, it is continually developing and strengthening a new value system shaped around the principle of sustainability, particularly in the realms of climate and energy policies [70].

Emission reduction plays a significant role in sustainability goals [71], and in this context, the transition to modern renewable sources like solar and wind energy in energy production stands out as one of today’s most important global environmental trends. Indeed, EU member states are working to align with this trend by rapidly increasing their installed modern renewable energy capacity [72]. In this regard, it would be useful to evaluate Türkiye’s targets set under its Nationally Determined Contribution within the framework of the Paris Agreement from the perspective of the global transition to renewable energy.

In this context, comparing the current modern solar energy capacity of Germany, the leading economy in the EU, with that of Spain, located on the Mediterranean coast and having similar climate conditions to Türkiye, will provide an important indicator for evaluating the need to strengthen Türkiye’s climate goals. The choice of solar energy for this comparison is based on its inclusion in Türkiye’s plans and policy documents [13] as one of the modern renewable energy sources, and its priority position in terms of installed capacity in the 2035 targets (Figure 3).

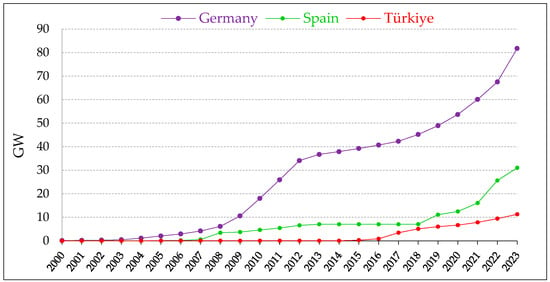

Figure 4 reflects the cumulative increase in installed solar energy capacity over the years for Germany, Spain, and Türkiye. It has seen Germany’s rapid expansion of installed solar energy capacity since 2008, reaching approximately 80 GW by 2023, positioning it significantly ahead of Spain and Türkiye. Spain has exhibited notable growth since 2018, achieving an installed capacity of approximately 31 GW in 2023 [12]. Türkiye, despite a later start, has demonstrated accelerated growth in recent years, reaching 11.29 GW in 2023. As of 2018, Türkiye’s installed capacity (5 GW) was relatively close to that of Spain (7 GW) [12]. However, Spain expanded its solar energy capacity by 338.7% from 2018 to 2023, whereas Türkiye recorded a 101% increase over the same period [12]. Consequently, by 2023, Spain’s installed solar capacity was nearly three times that of Türkiye. This trend highlights Türkiye’s progress in expanding its renewable energy capacity (solar) in the context of Paris Agreement commitments, providing a basis for evaluating both comparative advancements and the adequacy of national targets.

Figure 4.

Solar energy installed capacity—Germany, Spain, and Türkiye [12].

Another source that provides the opportunity to evaluate the current situation, recorded progress, and adequacy of the targets is the EU Türkiye Reports. For example, in the latest EU Türkiye Report—2024 [23], it is stated that, as of the publication date (30 October 2024), Türkiye has not yet adopted a climate law to support its 2053 climate neutrality target, nor has regulations for a national ETS and a long-term low-emission development strategy been approved. Also, it is claimed that Türkiye’s NDC under the Paris Agreement does not include concrete commitments for scientific emission reductions, particularly in the short and medium term, and that the emission reduction pledge is not sufficiently ambitious. Additionally, it is recommended that, before the UN Climate Conference (COP30), a new NDC be submitted that includes an absolute emission reduction target and a significantly enhanced contribution [23].

Therefore, the EU claims Türkiye needs to set more ambitious targets and take more concrete steps in the fight against climate change. Indeed, in order to achieve its own climate neutrality target, the EU Climate Law (2021) under Article 4, titled “Interim Targets”, establishes a binding target for the EU to reduce its net greenhouse gas emissions (after accounting for removals) by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels (Art. 4/1) [73].

In contrast, in its updated NDC [15], Türkiye has pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 41% by 2030 compared to the reference scenario based on 2012 levels. In contrast, in its updated NDC, Türkiye has pledged to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 41% by 2030 compared to the reference scenario based on 2012 levels. It should be noted, however, that Türkiye’s target does not include an absolute reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions like the EU’s; it is based on the principle of reducing emissions from an increase [15].

In Türkiye, the Climate Change Law Draft shared on the Western Mediterranean Exporters Association (WMEA) website under the “Reduction Targets” section states that greenhouse gas emissions will be reduced in line with the net-zero emissions target and the goals and policies outlined in the NDC (Art. 4/1) [74]. However, it appears that the draft does not include a legally binding emission reduction target [74].

The CLP was submitted to GNAT in February 2025. The official announcement states that greenhouse gas emissions will be reduced in line with the net-zero target and the NDC; however, it does not clarify whether the law includes a binding absolute emission reduction target [26].

In conclusion, there is a clear gap between the climate targets and trends under the Paris Agreement set by the EU and Türkiye’s current targets. To close this gap, it is necessary to reduce coal-based energy consumption and increase incentives for renewable energy sources [51]. By setting more ambitious emission reduction targets and transforming them into legally binding texts, Türkiye will strengthen its compliance with both the Paris Agreement and EU climate acquis, facilitating the closure of this gap. This situation has the potential to create a strong impact on increasing Türkiye’s exports to the EU.

3.3. Proposed Solutions and Strategies for Achieving the Targets

Given that the EU has taken global leadership in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and complying with the Paris Agreement [75], Türkiye’s core strategy should be to follow a path aligned with the EU in this area [76].

Closely monitoring the EU’s transformation under the European Green Deal and sustainability principles, as well as strengthening the alignment of national legislation with EU climate law, will support Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement. Additionally, more effective implementation of the updated national legislation will make the compliance process more efficient [77].

There may be other developing countries with similar characteristics to Türkiye, such as total population, total and per capita GDP, and installed capacity by energy source, some of which may be suitable as benchmarks for Türkiye’s Paris Agreement compliance steps. However, when it comes to emission reduction, adopting an approach aligned with the EU and selecting model countries from the EU is a more rational choice for Türkiye, as the EU is Türkiye’s largest export market [7].

Regarding compliance with the Paris Agreement, some EU member states stand out compared to others. Germany, with its comprehensive climate legislation and ambitious policies, leads these countries. The second model country, Spain, has similar characteristics to Türkiye, particularly in terms of the number of sunny days along the Mediterranean coast. Additionally, Spain has made significant progress in a short time in renewable energy, especially in the area of solar energy, which is also highlighted in Türkiye’s own plans and programs (Figure 4).

Table 2 compares the climate policies of Türkiye (Tr), Spain (Es), and Germany (De). The data in the table provide insights into the proposed solutions and strategies for achieving the targets.

Table 2.

Climate policies of Türkiye, Spain, and Germany. The symbols indicate that the elements are ✓: present and ✘: not present.

Table 2, reflecting the climate policies of Türkiye, Spain, and Germany, provides an opportunity to compare these countries based on specific parameters and assess Türkiye’s position in terms of legal regulations and targets in the fight against climate change. As emphasized earlier, Türkiye has not yet enacted a Climate Law containing absolute and binding emission reduction targets; however, such laws were enacted in Germany in 2019 and in Spain in 2021.

Regarding emission reduction targets, Türkiye relies on relative targets (from increase to reduction) [15], while Spain [25] and Germany [24] have absolute emission reduction commitments.

When looking at climate neutrality targets, Germany has set the year 2045, Spain has set 2050, and Türkiye has set 2053. Furthermore, Spain plans to phase out coal by 2030, and Germany by 2038, while Türkiye currently does not have an official binding target for coal phase-out (Table 2). This indicates that Türkiye needs to set more specific and ambitious targets in these areas.

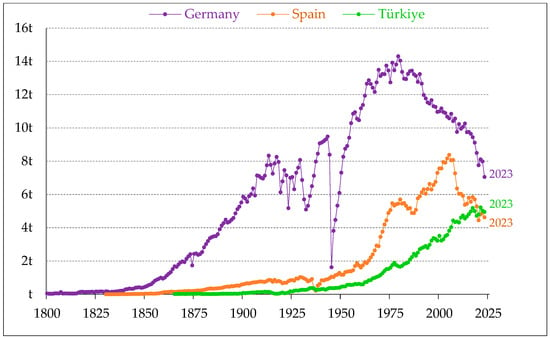

In terms of renewable energy investments, Türkiye’s installed solar energy capacity is limited to 11.29 GW [12], while its wind energy capacity stands at 11.70 GW [79]. In comparison, Spain and Germany have significantly higher capacities in these sectors (Figure 4). These differences indicate the need to evaluate the role of long-term planning and incentive mechanisms in the development of renewable energy investments in Türkiye. Additionally, comparing the direction and pace of emission reduction efforts over the years between Germany, Spain, and Türkiye will provide a different perspective on the direction and pace that Türkiye should adopt for its emission reduction efforts. Indeed, Figure 5 reflects the change in per capita carbon emissions over the years for Türkiye, Spain, and Germany.

Figure 5.

Per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and industry: Germany, Spain, and Türkiye [40].

Spain’s per capita carbon emissions peaked in 2005 by reaching 8.4 tons, followed by an accelerating downward trend [40]. Türkiye’s carbon emissions were 5 tons per person, while Spain’s have declined to 4.6 tons in 2023. Consequently, in 18 years between 2005 and 2023, Spain’s per capita emissions have decreased by 45.3% (Figure 5).

Per capita carbon emissions peaked in Germany in 1979 at 14.3 tons, followed by a significant downward trend, particularly after 1990 [40]. In 18 years between 2005 and 2023, Germany’s per capita emissions have decreased by 33% (Figure 5).

Meanwhile, in Türkiye, per capita emissions increased by 31% (Figure 5), as Türkiye’s installed energy capacity—and so its development—still heavily relies on fossil fuels [13]. Energy production facilities and industrial plants require considerable capital. There is already an established investment, employment, and production capacity based heavily on fossil fuels, which generate high greenhouse gas emissions [47]. Aligning Türkiye’s emission trajectory with that of Germany and Spain requires improved access to affordable international financing and grants [15]. Despite its classification as a developing country under the Paris Agreement [5], Türkiye faces limited access to such funds, partly due to its non-EU status. Without enhanced financial support, a rapid energy transition could risk job losses, social unrest, and economic instability [80].

In addition to financial constraints, certain structural characteristics within Türkiye’s climate governance present challenges for effective and sustained emission reduction efforts. Unlike Germany, where climate policies benefit from long-standing institutional mechanisms and legally binding emission targets, Türkiye’s institutional landscape is still in the process of evolving toward more integrated and enforceable frameworks. The absence of a comprehensive Climate Act and the relatively limited coordination between relevant administrative units may constrain the full integration of long-term emission targets into national planning. These institutional dynamics, rather than legislative differences alone, help explain part of the divergence in emission trajectories.

However, Türkiye’s increased trend in per capita emissions indicates the need for faster implementation of decarbonization policies. Therefore, it is crucial to shape the climate law framework with binding and ambitious targets at the legislative level, accelerate renewable energy investments, strengthen energy efficiency policies, and reduce fossil fuel dependence. These actions are beneficial for Türkiye to achieve its emission reduction targets and comply with the Paris Agreement.

In this context, it would be useful to examine the details of these two countries that could be models for Türkiye. However, further research should be carried out in order to provide insights to address the structural issues regarding climate governance in Türkiye, including the evolving role of inter-institutional coordination, implementation capacity, and policy prioritization in shaping long-term climate strategies.

3.4. International Examples (Germany and Spain)

3.4.1. Germany

Germany is among the countries with comprehensive legislation for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The German Federal Climate Protection Act (Klimaschutzgesetz-KSG) [27] and the Renewable Energy Sources Act (Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz-EEG) [81] have binding targets regarding emission reduction and the transition to renewable energy. This section aims to examine these laws and propose potential solutions for Türkiye.

Germany’s climate policy is shaped by KSG, enacted in 2019, which provides a comprehensive and ambitious legal framework for the country’s compliance with the Paris Agreement and its target of achieving greenhouse gas neutrality by 2045 (Art. 1). As stipulated in the Act, binding emission reduction targets have been set, such as a minimum of 65% by 2030 and at least 88% by 2040, compared to 1990 levels (Art. 3/1). These targets are relevant to facilitate and ensure a structured, accountable, and transparent transition towards a low-carbon economy.

The annexes of the KSG clearly specify Germany’s total annual emission targets for the period 2020–2030, as shown in Table 3. These figures indicate a gradual year-on-year reduction in national emissions, with all targets made legally binding under the KSG framework.

Table 3.

Germany’s gradual emission reduction—quantity targets (KSG, Annex-2) [24].

Table 4 presents the proportional emission reduction targets set for the period 2031–2040, expressed as percentages relative to 1990 levels. When Table 3 and Table 4 are considered together, it becomes evident that Germany has adopted a legally binding, long-term, and absolute approach to greenhouse gas emission reduction. As a result, KSG can provide a model for Türkiye in the following ways:

Table 4.

Germany’s gradual emission reduction—proportional targets (KSG, Annex-3) [82].

- Updating the Climate Law, which was submitted to the GNAT in February 2025, to set gradual absolute emission reduction targets (Art. 4/1; Annex-2) [24].

- Establishing a flexible framework, giving the government the authority to modify annual emission budgets through regulation if necessary (Art. 4/3) [27].

- Creating an independent monitoring and reporting mechanism by establishing a scientific committee to evaluate whether annual emission targets are met (Art. 12) [27].

- Strengthening energy efficiency measures in public buildings, inspired by the role of public authorities as role models (Art. 13 and Art. 15) [27], could serve as an example for Türkiye in enhancing energy efficiency in public buildings.

While implementing the specified legal and political changes, some issues must also be taken into account. For example, as a developing country, Türkiye would face a deeper transformation—particularly in greenhouse gas-intensive sectors such as energy—if it were to adopt binding and legal climate targets. This transformation is directly dependent on the availability of strong and cost-effective financial flows [15]. Therefore, the incorporation of binding emission reduction targets into the Turkish Climate Law, inspired by the German Climate Law, must be supported by financial mechanisms to ensure that Türkiye’s development is not hindered [15]. Likewise, the ability of the government to revise annual emission targets when necessary is of critical importance to prevent the risk of slowing economic growth [27].

From the perspective of the Renewable Energy Sources Act, the German EEG [81] aims to facilitate the move to a fully renewable energy-based electricity supply (Art. 1/1). To achieve this, an interim target has been included for the share of electricity produced from renewable energy sources in gross electricity consumption to reach at least 80% by 2030 (Art. 1/2) [83]. Furthermore, the transition to renewable energy is required to be continuous, cost-effective, and environmentally sustainable (Art. 1/3) [83].

One notable aspect of the law is that the construction and operation of renewable energy plants and auxiliary facilities must be based on the principle that they serve the “public interest”, contributing to public health and safety. The law also establishes the principle that renewable energy will be prioritized in the evaluation of protected interests until the country’s electricity production is nearly greenhouse gas neutral (Art. 2) [83]. Another noteworthy aspect is that starting from 2024 until 2040, capacity increase targets for onshore and offshore wind turbines are set in the law for every two-year period (Art. 4) [83].

The law stipulates that operators of the specified types of plants must provide financial support to municipalities affected by the construction of their facilities. In this context, plant operators can offer unilateral, non-repayable grants to the affected municipalities (Art. 6/1) [83]. This regulation allows for flexible negotiation and agreement with local authorities without imposing additional financial burdens on companies operating renewable energy plants.

These types of agreements between municipalities and plant operators are not considered bribery or similar interests under the German Penal Code (Strafgesetzbuch-StGB), particularly under Articles 331–334 [84]. This rule also applies to similar agreement proposals and related grants (Art. 6). As a result, the following recommendations for Türkiye were identified:

- Based on the legal principle in the EEG that renewable energy projects serve the public interest and should be prioritized (Art. 2) [83], Türkiye could also prioritize these projects in its administrative and legal processes.

- Under the EEG, Germany aims to increase the share of renewable energy in electricity consumption to at least 80% by 2030 (Art. 1/2) [83]. Similarly, Türkiye could accelerate the renewable energy transition by setting binding, legal interim targets for specific dates.

- Under the EEG, in Germany, operators of certain renewable energy plants can offer non-repayable grants to municipalities affected by the projects (Art. 6) [83]. A similar support and negotiation framework could be incorporated into Türkiye’s legislation to ensure the integration of local governments in such projects.

- Under the EEG, Germany has set periodic capacity increase targets for onshore and offshore wind turbines until 2040 (Art. 4) [83]. Türkiye could also integrate long-term, regular, and binding legal capacity increase targets into its legislation.

However, it is important to emphasize the following point as well: although Türkiye has made significant investments in renewable energy [68], it tends to continue operating thermal power plants throughout their economic lifespan in order to avoid slowing down development and to maintain energy supply security [62]. For instance, the protests against deforestation in the Akbelen Forest—carried out to expand open-pit mining activities supplying coal to a thermal power plant in the Southern Aegean region—demonstrated strong support from civil society organizations and local communities for the closure of such plants [85]. However, the protests did not yield any concrete results. The government’s approach to prioritizing energy supply security prevailed, and the thermal power plant was permitted to convert the pine forest into a coal mining area [86]. This situation clearly indicates that Türkiye’s transition to renewable energy is conditional on not compromising its energy security and development objectives.

3.4.2. Spain

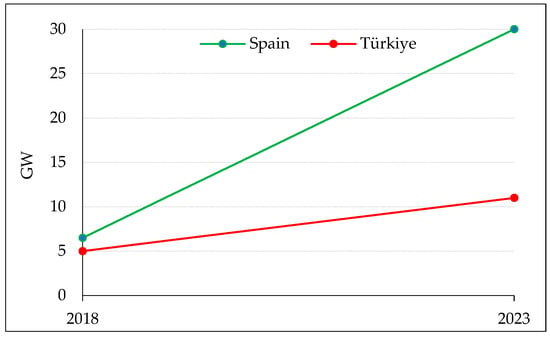

Spain’s progress in renewable energy (especially solar energy) (Figure 6) and its ambitious targets [87] provide valuable insights into how Türkiye can develop more effective legislation and policies for compliance with the Paris Agreement. Therefore, the aspects that Türkiye can adopt as a model have been evaluated.

Figure 6.

Installed solar energy capacity of Türkiye and Spain (2018–2023) [12].

Among EU members, Germany leads by a large margin in total renewable energy capacity [88]. But Spain also has accelerated its solar energy investments, especially since 2018 [89], positioning itself ahead of Türkiye (Figure 4 and Figure 6). Compared to Germany, Spain’s installed solar energy capacity is closer to Türkiye’s (Figure 4) and its high number of sunny days due to its Mediterranean climate makes it a suitable model for the Paris Agreement and renewable energy (solar) targets.

Spain had an installed solar capacity of 7.07 GW in 2018 when it began to speed up solar investments, while Türkiye’s capacity was at 5.06 GW. That was when the two countries’ solar installed capacity values were nearly the same. According to 2023 data, Spain increased its installed capacity by approximately 338%, reaching 31.02 GW, while Türkiye showed a significant 101% increase during the same period (Figure 4). However, in the five years between 2018 and 2023, Spain’s rapid growth widened the gap between the two countries, with Spain leading (Figure 6).

Since 2018, Spain has rapidly increased its installed solar energy capacity (Figure 6). When examining the key factors that triggered developments in this area, it is evident that in 2018 the European Union enacted Directive 2018/2001 on the Promotion of the Use of Renewable Energy Sources (Renewable Energy Directive—RED II) [90]. According to Article 3, titled “Binding General Union Target for 2030”, the Member States are required to ensure that by 2030, at least 32% of the total final energy consumption in the Union comes from renewable sources, thus accelerating both the energy transition process and Paris Agreement compliance steps. However, it should be noted that this 32% target was later increased to 42.5% in the subsequent years (Art. 3/1) [72]. In the same year, Spain enacted the Royal Decree-Law (RDL) 15/2018 [91], which significantly accelerated renewable energy (especially solar) investments (Figure 6). According to this decree, Spain intends to carry out the following:

- The previous regulations, which required individuals, groups, or companies generating and consuming their own electricity to bear additional costs, were eliminated under the RDL 15/2018. Self-consumed energy generated from renewable sources was exempted from all kinds of fees and tariffs (Art. 18/5).

- The RDL 244/2019 [92] on the Administrative, Technical, and Economic Conditions for Self-Consumption of Electricity established the legal framework that allows multiple individuals or groups (such as apartments, neighborhoods, or cooperatives) to produce and consume their electricity together (Art. 4).

- ▪

- In the Climate Change and Energy Transition Law (Law 7/2021), enacted on May 20, 2021 [25], Article 3 outlines the “reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy, and energy efficiency targets”. The following goals are set for 2030:

- ▪

- A reduction in emissions by at least 23% compared to 1990 levels (Art. 3/1-a) [25].

- ▪

- An increase in the share of renewable energy in final energy consumption to at least 42% (Article 3/1-b) [25].

- ▪

- Ensuring that at least 74% of electricity production is sourced from renewable energy sources (Article 3/1-c) [25].

Considering the Above Regulations

- The CLP submitted to the GNAT in February 2025 can be updated based on the 2018/2001 EU Renewable Energy Directive [90] and the Spanish Climate Law (Law 7/2021) [25], setting binding and ambitious targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, increase the share of renewable energy in total final energy consumption, and raise the proportion of renewable energy usage in electricity production. Taking such a step would accelerate the energy transition and strengthen Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement.

- By leveraging Spain’s RDL 15/2018 [91], Türkiye can more strongly encourage consumers to produce their own electricity. The mechanism for selling excess production to the grid or offsetting could be updated to be more consumer-friendly, flexible, and incentive-based.

- Similar to Spain’s RDL 244/2019 [92], an inclusive and flexible legal framework could be created in Türkiye to enable community-based solar energy production (such as in apartments, neighborhoods, or cooperatives).

Such regulations or updates could accelerate Türkiye’s solar energy investments, support the energy transition, and strengthen Türkiye’s compliance with the Paris Agreement.

In addition to strengthening renewable energy capacity, another issue related to compliance with the Paris Agreement is the selection of areas for solar energy investments. Unfortunately, in Turkey, news occasionally surfaces in the public sphere about the cutting down of numerous trees (for example, olive groves, pine forests, and others in the Southern Aegean) during the construction of solar power plants [93]. Forests are carbon sinks, and therefore protecting them helps countries resist climate change and thus better comply with the Paris Agreement, particularly under Article 5 [1]. In our opinion, the preservation of local tree communities, such as olive groves, should also be regarded as a crucial component of alignment with both the Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal [94]. To reduce these shortcomings, strengthening “public participation” in Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) processes could enhance the perception of legitimacy among environmental NGOs and local communities during the transition to renewable energy [95].

4. Conclusions

This study has provided a comparative analysis of Türkiye’s alignment with the Paris Agreement, focusing on legal, institutional, and policy-based challenges by examining the experiences of Germany and Spain. The findings highlight the need for Türkiye to address key structural deficiencies, particularly the absence of enforceable legal frameworks, limited access to international climate finance, and institutional coordination weaknesses.

To fully align with the Paris Agreement and maintain its competitiveness within the EU market, Türkiye must enact a comprehensive climate law that introduces absolute and binding targets while respecting national development priorities. The successful practices of Germany and Spain show that long-term planning, effective use of carbon pricing mechanisms, and promotion of community-based renewable energy models can create tangible outcomes. Türkiye’s future pathway should integrate these lessons through tailored reforms and operationalize a domestic ETS with a well-managed pilot phase.

That said, it is essential to point out several limitations that may impact the interpretation and generalizability of the findings. The analysis does not provide multi-level policy dynamics or regional and sectoral differences, all of which are essential to understanding the full scope of climate policy implementation, and relies primarily on secondary sources, such as valuable government documents, policy reports, and statistical data. However, these may reflect prevailing institutional narratives and limit the granularity of the analysis. The absence of fieldwork, including interviews or observational data, constrains insights into implementation challenges on the ground. The exclusive focus on national-level policies and emission trends also overlooks subnational heterogeneity. Finally, although Germany and Spain provide relevant EU case studies, the omission of comparator countries with different socio-economic contexts may limit the generalizability of the conclusions.

In light of these gaps, future research may focus on the practical aspects of climate policy implementation in Türkiye, particularly at the local level. Emphasis should be placed on pilot applications, sector-specific assessments of market-based instruments such as ETS, inter-institutional coordination, and the degree of policy coherence during the green transition. Furthermore, studies that explore public participation, social acceptance, and the adaptability of EU policy models to Türkiye’s unique administrative and socio-political landscape would offer meaningful contributions. Advancing research in these directions will not only strengthen Türkiye’s strategic and legal climate policy architecture but also enhance its operational effectiveness and long-term resilience.

Ultimately, Türkiye’s alignment with the Paris Agreement is not solely an environmental commitment but a strategic necessity. In an increasingly climate-conscious global economy, achieving a just and effective transition will depend on the country’s ability to ensure legal clarity, policy consistency, and the mobilization of sustainable investments.

Author Contributions

Conceptual approach and methodology, A.B.; writing—original draft, A.B.; supervision, G.S.-A.; visualization, G.S.-A.; writing—review and editing, G.S.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study covers Akin Batmaz’s part of a doctoral thesis under the supervision of Goknur Sisman-Aydin. We thank Kemal Simsek for his valuable support in editing this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| BAU | Business as Usual |

| CBAM | EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| CLP | Climate Law Proposal |

| COP30 | 30th Convention of Parties to UNFCCC |

| DCC | Directorate of Climate Change, Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, the Republic of Türkiye |

| De | Germany |

| EC | European Commission |

| Es | Spain |

| ETS | Emissions Trading System |

| EU | European Union |

| GCB | Global Carbon Budget |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GNAT | Grand National Assembly of Türkiye |

| GW | Gigawatt |

| KSG | German Federal Climate Protection Act |

| ktCO2eq | Kilotons of CO2 equivalent |

| Law 7/2021 | Climate Change and Energy Transition Law, Spain |

| MEUCC | Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, the Republic of Türkiye |

| MtCO2eq | Metrictons of CO2 equivalent |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| NEP | National Energy Plan |

| RDL | Royal Decree-Law, Spain |

| Tr | Türkiye |

| TURKSTAT | Turkish Statistical Institute |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| WB | World Bank |

| WMEA | Western Mediterranean Exporters Association |

References

- UNFCCC. Paris Agreement. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/english_paris_agreement.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Bodansky, D. The Paris Climate Change Agreement: A new hope? Am. J. Int. Law 2016, 110, 288–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajamani, L. The 2015 Paris Agreement: Interplay between hard, soft and non-obligations. J. Environ. Law 2016, 28, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.; Wong, D. Soft law in the Paris Climate Agreement: Strength or weakness? Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2017, 26, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OG. Paris Agreement–7.10.2021/31621 (Duplicate Issue); Decision Number: 4618; Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye; Official Gazette of the Republic of Türkiye: 2021. Available online: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2021/10/20211007M1-1.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025). (In Turkish)

- EC. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). 26 February 2025. Available online: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- MT. Export Analysis by Country Groups; The Ministry of Trade (MT): Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024. Available online: https://ticaret.gov.tr/haberler/ticaret-bakanligi-ulke-gruplarina-gore-ihracat-analizi-yapti (accessed on 15 March 2025). (In Turkish)

- Koç, B.E.; Kaynak, S. The possible effect of the carbon border adjustment mechanism on Turkey-EU-27 foreign trade relationship. J. Product. 2023, 57, 273–288. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çimen, Z.A. Carbon Regulation at the Border and Türkiye’s Global Competitiveness in Selected Sectors. Polit. Ekon. Kuram. 2024, 8, 1–17. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WB. Population, Total—Türkiye and Germany. United Nations Population Division; World Population Prospects: 2024 Revision; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=TR-DE (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Üstün, K.T. The beginning of a new era: The European Green Deal and its impacts on Turkish environmental law and policies. Memleket Siyaset Yönetim (MSY) 2021, 16, 329–366. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/msydergi/issue/68237/1063473 (accessed on 25 February 2025). (In Turkish).

- IRENA. Installed Solar Energy Capacity: Spain, Türkiye; International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA): Masdar City, United Arab Emirates, 2024; Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/installed-solar-pv-capacity?country=ESP~TUR~DEU (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- MENR. Türkiye National Energy Plan. The Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources (MENR) of the Republic of Türkiye. 2022. Available online: https://enerji.gov.tr/Media/Dizin/EIGM/tr/Raporlar/TUEP/T%C3%BCrkiye_National_Energy_Plan.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Charalampidis, I.; Taranto, Y. Net Zero 2053: Socioeconomic Impacts of the Transition to Carbon-Free Energy in Türkiye; SHURA Energy Transition Center: Istanbul, Türkiye, 2024; ISBN 978-625-6956-56-8. Available online: https://shura.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/SHURA-2024-10-Net-Zero-2053-Socioeconomic_ENG.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- MEUCC. Updated First Nationally Determined Contribution. The Ministry of Environment, Urbanization and Climate Change (MEUCC) of the Republic of Türkiye; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC); 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/NDC/2023-04/T%C3%9CRK%C4%B0YE_UPDATED%201st%20NDC_EN.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Schramm, L.; Krotz, U. Leadership in European crisis politics: France, Germany, and the difficult quest for regional stabilization and integration. J. Eur. Public Policy 2024, 31, 1153–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. List of Parties That Signed the Paris Agreement on 22 April. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, UN. 2016. Goal 13: Climate Actions, News. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2016/04/parisagreementsingatures/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database: Emerging Market and Developing Economies—Emerging and Developing Europe 2024, October. 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/select-countries?grp=2903&sg=All-countries/Emerging-market-and-developing-economies/Emerging-and-developing-Europe (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database. Major Advanced Economies (G7). 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/select-countries?grp=119&sg=All-countries/Advanced-economies/Major-advanced-economies-(G7) (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Database. Euro Area. 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/select-countries?grp=995&sg=All-countries/Advanced-economies/Euro-area (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- European Commission (EC). EU Enlargement: Candidate Countries. Communication From the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2014-15. (COM/2014/0700). Document 52014DC0700. 2014. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/eu-enlargement_en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- EU. European Union Countries. 2025. Available online: https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/eu-countries_en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- EC. Türkiye 2024 Report; European Commission (EC): Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/8010c4db-6ef8-4c85-aa06-814408921c89_en?filename=T%C3%BCrkiye%20Report%202024.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- BGBI. Annex 2 Climate Protection Act (KSG) FLG I 2019,2519. Federal Climate Protection Act. Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBI.) (Federal Law Gazette), Germany. 2019. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ksg/anlage_2.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- BOE. Climate Change and Energy Transition Law (Law 7/2021). Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE)-Official State Gazette, Spain. 20 May 2021. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2021-8447 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- GNAT. Türkiye’s First Climate Change Law Proposal. Grand National Assembly of Türkiye-GNAT News. 20 February 2025. Available online: https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/Haber/Detay?Id=77e291f5-6b4a-4bb6-b157-0195286c4403 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- BGBI. Federal Climate Protection Act (Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz–KSG). Bundesgesetzblatt (BGBI.) (Federal Law Gazette), Germany. 2019. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ksg/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- FGG. Ending Coal-Generated Power: The German Coal Phase-Out Act (Kohleausstiegsgesetz). Federal Government of Germany (FGG). 2020. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/service/archive/kohleausstiegsgesetz-1717014 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- MITECO. National Integrated Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC 2023–2030). The Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge (MITECO) of Spain. 2024. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/energia/files-1/pniec-2023-2030/PNIEC_2024_240924.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Fernández, L. Renewable Energy Capacity Installed in Germany in 2023 and Targets for 2030, by Source. Statista. EMBER. 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1468460/renewable-capacity-targets-by-source-germany/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- TURKSTAT. Foreign Trade Statistics, January 2025; Turkish Statistical Institute (TURKSTAT): Ankara, Türkiye, 2025. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Foreign-Trade-Statistics-January-2025-53900 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- DESTATIS. In 2024, United States Became Germany’s Most Important Trading Partner Once Again After Nine Years; Federal Statistical Office of Germany (DESTATIS): Wiesbaden, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Press/2025/02/PE25_063_51.html (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS); World Bank (WB). Spain Trade Summary. 2023. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/countrysnapshot/en/ESP (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- BGBI. Federal Climate Change Act (KSG), Section 3(1). Official Gazette, Federal Ministry of Justice (BMJ), Germany. 2021. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/ksg/KSG.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2024: No More Hot Air … Please! With a Massive Gap Between Rhetoric and Reality, Countries Draft New Climate Commitments; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS); World Bank (WB). Mexico Trade Summary: Top 5 Products Exports and Imports at HS 6-Digit Level. Mexico Trade Summary 2022 Data. 2022. Available online: https://wits.worldbank.org/CountrySnapshot/en/MEX/textview (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Development Indicators; World Bank. Population, Total—China (2023 Data). 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=CN (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- WB. GDP per Capita (Current US$)—Türkiye; WB: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=TR (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Global Carbon Budget (GCB). Per Capita CO2 Emissions: Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions from Fossil Fuels and Industry. (EU and Türkiye) Our World in Data. Population Based on Various Sources. 2024. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/co-emissions-per-capita?tab=chart&country=TUR~OWID_EU27 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- GCB. Per Capita CO2 Emissions from Fossil Fuels and Industry: Germany, Spain, Türkiye; Global Carbon Budget: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/co-emissions-per-capita (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Liu, H.; Evans, S.; Zhang, Z.; Song, W.; You, X. The Carbon Brief Profile: China; Carbon Brief Ltd. © 2025: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://interactive.carbonbrief.org/the-carbon-brief-profile-china/index.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Karakaya, E. Paris Climate Agreement: Its content and an evaluation on Turkey. Adnan Menderes Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 3, 1–12. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]