Abstract

The demolition and resettlement of urban villages is a new urbanization strategy widely used by the Chinese government. It is a massive development intervention designed and implemented by the Chinese government to promote the relocation and resettlement of the rural-to-urban population. However, limited research has focused on how rural residents adapt to their new urban lives within these large-scale relocation and resettlement projects. This paper aims to analyze this adaptation process. This study employs Lefebvre’s spatial production theory, based on a survey of 256 resettled residents in Qingdao, China, using a structured questionnaire and the statistical analysis software SPSS 24.0 to quantitatively evaluate the adaptability of resettled residents based on three dimensions: material space, institutional space, and social space. Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses are conducted to explore the relationships among these dimensions. Our findings reveal an association between high adaptation levels and urban resident identity recognition among the resettled residents. Our research findings raise more substantial concerns about the transparency of government decision-making and the community participation of resettlers in the current resettlement process.

1. Introduction

1.1. Urban Villages in the Context of Urbanization in China

Urban villages are unique phenomena arising from China’s rapid urbanization. The term seemingly combines two contradictory elements: “urban” and “village”. Urban villages are rural settlements that have been engulfed by urban expansion but retain their traditional rural governance structures, land ownership patterns, and lifestyles. These villages exist as transitional spaces, blending rural and urban characteristics, and often face governance, infrastructure, and social challenges.

The emergence of urban villages is closely tied to China’s dual land ownership system, where urban land is state-owned and rural land is collectively owned by village collectives. As cities expand, rural land near urban areas is requisitioned for urban development, leaving the original rural settlements in a liminal state, neither fully urbanized nor entirely rural. This process reflects the broader socio-economic transformations accompanying China’s modernization efforts.

Since 1992, when the urban village renovation program was initiated following the reform and opening up, the government has been implementing large-scale relocation and resettlement programs to promote the democratization of the agricultural transfer population. However, in recent years, the urban village resettlement project has been further intensified against the backdrop of the sustained downturn in China’s real estate industry. On 15 November 2024, the central government issued a notice that the scope of the policy support for the transformation of urban villages will be further expanded from the initial 35 super-mega megacities and megacities with an urban resident population of more than 3 million to nearly 300 prefecture-level cities and above. According to the National New Urbanization Plan (2021–2035), the steady implementation of urban village transformation has a key influence on the speed and quality of new urbanization development. Rural–urban migration aligns with the central government’s new urbanization strategy; consequently, due to the higher financial inputs and wider range of follow-up support, urban village renovation is considered an important way to solve the problems of agriculture, rural areas and farmers. In the coming period, the systematic reconstruction of urban villages’ spatial, economic, and social functions will be one of the important ways for prefecture-level cities to promote new urbanization.

The scale of the urban village transformation in China is enormous. At the same time, this strategy of rural-to-urban migration has been conceived as a particular form of urbanization involving the reproduction of spatial changes, social relations and political structures [1,2]. The fundamental aspect of urban village redevelopment lies in integrating these areas into the unified regulatory framework of the city, rather than simply “erasing” them spatially. In other words, the gradual transition from a “dual regulatory” environment to a “unified regulatory” framework is essential for addressing the underlying issues, and this first requires municipal governments to shift away from profit-driven “growth machine” policies and instead adopt a more comprehensive and holistic development policy framework [3]. Examining urban–rural integration from the perspective of spatial organization enables a deeper understanding of the intrinsic organizational mechanisms governing economic, social, cultural, and ecological spaces, as well as the behavioral activities within the urbanization process. Such an approach provides scientific support for the implementation of urbanization and coordinated urban–rural development strategies [4,5].

From 2009 to the present, there has been a significant shift in the value judgments of urban villages within the academic community. This shift has led to advocacy of a pluralistic governance goal of coordinated spatial, social, and economic development. Additionally, scholars have begun to acknowledge stakeholders such as new citizens [6]. Unlike rural residents who independently migrate to large cities in search of better living conditions, the urban village resettlement discussed in this paper is a state-organized renovation project in which rural residents are relocated to modern residential areas close to their original village sites, where the government directly intervened in the lives of the resettled residents and played a dominant role in the urban life they subsequently turned to.

1.2. The Theory of Spatial Production: A Comprehensive Framework for the Study of Urban Villages

1.2.1. The Essence of New Urbanization Is People-Oriented Urbanization

The significant transition from rural to urban and village to citizen over a relatively brief period necessitates swift adaptation to new living spaces and lifestyles by resettled populations. This process can profoundly impact their livelihoods, social relationships, and well-being. The fundamental principle of new urbanization is human-centered urbanization. In this regard, the urbanization of people assumes paramount importance in the process of urban village transformation, making the urbanization of people a pivotal aspect and serving as a key determinant of success in urban village redevelopment projects [7,8]. The capacity of resettled residents to adapt is essential to the success of large-scale urban village resettlement projects in China and the efficacy of subsequent support measures following resettlement.

However, practices and studies concerning urban village redevelopment indicate that the government and enterprises primarily drive the transformation process, with villagers’ interests being disregarded and their status as the primary concern being overlooked [9]. The communication and participation mechanisms, both “top-down” and “bottom-up”, are not functioning optimally [10]. Following the redevelopment, the “rural villagers” have become “urban citizens”, resulting in the loss of land welfare guarantees they previously enjoyed. This is further exacerbated by the relatively weak position of villagers among the three parties involved, leading to intensified conflicts during the urban village transformation process [11]. These processes prioritize the urbanization of landscapes over the urbanization of people. The transformation of urban villages in various places primarily entails the recreation of the landscape environment, while measures to support the urban transformation of villagers are often lacking, resulting in a significant lag in the urbanization process of people [12]. Urban village redevelopment is not merely a reshaping of the landscape but also a process of reproducing social space in urban villages [13].

1.2.2. Current Status of Research on Urban Villages in the Context of New Urbanization

Overall, the existent research in academia has predominantly centered on transforming urban villages into urban spaces, with a paucity of attention devoted to the adaptation of the millions of resettled individuals during large-scale urban village renovations to their new urban environment. At the core of Lefebvre’s materialist theory of space production lies the concept of individuals who exist in corporeality and sensuousness. These individuals possess a corporeal and sensuous existence characterized by their unique feelings, imagination, thinking, and consciousness [14].

Regarding the research content, the academic community has comprehensively investigated urban villages’ spatial, land, system, and societal dimensions. In contrast, the theory of spatial production can incorporate the dimensions of cities and spaces systematically into a concise but comprehensive social theory, enabling individuals to comprehend and analyze spatial processes across diverse levels [15]. Lefebvre’s theories, represented by “The Production of Space” and “Critique of Everyday Life”, have opened up numerous problem areas, which are deeply related to the current reality of China [15]. These theories offer a profound lens through which to unravel the underlying “root causes” of these complex issues.

From the perspective of the research area, urban village research has distinctive regional characteristics. East China is a typical example of the rapid development of urbanization. It is the region where the phenomenon of urban villages occurs most frequently, and it is also the most desirable research area. At present, there are more studies in eastern China, but the cases are dominated by Guangdong and Beijing. In contrast, Qingdao is the largest city in Shandong Province, the first practice area of China’s new urbanization, and one of the fastest-growing megacities in terms of population growth, during which urban villages have emerged in large numbers and become a major challenge for urban development. However, the body of research literature on urban villages in Qingdao is relatively small compared to other developed cities in the east, making Qingdao a typical sample for studying the adaptability of urban village transformation in eastern coastal cities.

In terms of the research focus, several studies related to spatial production theory have emerged in the field of urban planning in China since 2009, as evidenced by the works of [16,17,18,19]. However, domestic research often reflects a disconnect between philosophical (epistemological) approaches and spatial practices [20]. Most research only briefly introduces specific works, lacking a profound sense of empathy and in-depth understanding [21]. The strong tendency toward reductionism and scientism leads to an involuntary slip into the cognitive realm of spatial political economy when interpreting the reality of social space [20]. This perspective remains above the superstructure (ideology, state power, policies, and institutions), unable to penetrate deeply and sink to the foundation and microscopic daily life. In the context of urban village renovation, a pivotal question emerges: How can we foster the creation of the poetry of daily life? This endeavor, in turn, will contribute to the innovation and development of the disciplinary knowledge system of spatial practice.

With respect to the research methodologies, the majority of urban village research from the perspective of spatial production theory is qualitative, with limited quantitative research. Among the few quantitative studies, the epistemological logic often aligns more closely with Harvey’s spatial political economy.

1.2.3. The Theory of Spatial Production: A Comprehensive Framework for the Study of Urban Villages

In summary, this paper evaluates the adaptability of the living space and identity transformations brought to the resettled people by the urban village renovation project, with a particular focus on the corporeal experiences and daily practices of the resettled people. Based on Lefebvre’s dialectical triad of the production of space, this study focuses on three dimensions of inquiry in the resettlement of urban villages. (1) From the dimension of spatial practices, how does the material space of resettled people adapt to urban life after their resettle? (2) From the dimension of representations of space, how do resettled people adapt to the shift in institutional space during the resettlement process? (3) From the dimension of representational spaces, how do resettled people feel about their daily practices during the process of identity transformations? In the next section, we will explore Lefebvre’s triadic dialectic of space production in more detail. The Section 3 describes the research site and data collection methods. Subsequently, this paper will describe our findings on the adaptability of resettled people in the transformation of urban villages through the three dimensions of spatial production: the material, institutional, and social dimensions. Finally, this paper will discuss the key implications of the findings.

2. Theoretical Analysis of the Adaptability of Urban Villages Based on the Dialectics of the Three Elements of Spatial Production

2.1. The Complexity of Urban Village Adaptation with Villagers as the Main Body

There is a large body of literature on the adaptation of resettled people in urban villages, focusing on the process of gradual changes in daily life [22,23,24], acculturation and intercultural migration [25,26], and immigrant integration [27]. These complex processes contrast with the way resettlers’ urban adaptation mechanisms are usually considered in the context of urban village transformation: resettlers’ urban adaptation ranges from shifts in non-agricultural livelihoods to cultural, behavioral, and cognitive changes, and finally, to changes in residential status [28,29]. The assumption here is that once the physical transformation of the urban village is complete, resettlers are also utterly detached from rural society and fully integrated into the urban environment. For a long time, studies on resettlement in China have challenged these assumptions, pointing to more complex processes.

A critical concept in understanding urban villages is the “hukou” system, China’s household registration system. This system categorizes citizens as either rural or urban residents, determining their access to social services, education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Rural residents often face institutional barriers when migrating to urban areas, limiting their integration into urban society. This dual system has historically reinforced the divide between urban and rural populations, contributing to the unique challenges faced by residents of urban villages during resettlement and urbanization. In this section, we draw on the materialist triadic dialectic of Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production to develop a triadic dialectic argument in the problematic area of the dual system in urban villages and to construct our analysis of resettled people’s adaptation.

2.2. An Adaptation Analysis Framework for Urban Villages Based on the Dialectical Triad with Villagers as the Main Body

2.2.1. Understanding of Spatial Production Theory in the Field of Urban Planning in China

Since its inception, Lefebvre’s theory of “the production of space” has undergone three important dissemination processes in the Anglo-American academy. In the first two disseminations, spatial production has been interpreted from different perspectives [30,31,32,33]. It can be said that both L. Althusser’s structuralism and Harvey’s spatial theory keep capitalism in a perpetually closed, crisis-regenerating deterministic state, whereas, in fact, the core vitality of Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space is the search for new, possibly hopeful paths and political practices for the creation and transformation of social life out of the insurmountable inherent spatial contradictions and crises of capitalism [34]. In Chinese academia, this understanding is more evident and severe in urban planning and geography. Most urban planning papers that claim to adopt “the production of space” as a theoretical framework are, in essence, rooted in Harvey’s spatial political economy [35,36,37,38,39,40]. In terms of spatial practice alone, the Chinese academic community has mainly focused on the interpretation of Lefebvre’s late work The Production of Space and has not paid enough attention to some of the topics that he focused on in his early and middle years (such as “daily life” and “the state”), nor has it delved into the core of his philosophy and epistemology (dialectics, historical materialism). As Liu Huaiyu pointed out, “Due to the French language barrier and the professional limitations of researchers, most domestic research remains at a brief introduction to his individual works, and there is little ‘sympathetic’ in-depth understanding, and even less overall and comprehensive research, which is basically divorced from Lefebvre’s extremely complex and rich and varied micro-world of thought and creative context” [41]. Whether they are academics, government departments, or practitioners, if they look at the urban problem only from the perspective of the mechanism of capital accumulation and the surplus value cycle, they tend to ignore human agency and erase the possibility of creation. To break this impasse, it is first necessary to break through the entrenched cognitive paradigm.

Lefebvre conceptualizes space as a concept of social production arising from a sequence and series of action processes [42] (p. 73). This production is not a production in space but a production of space itself [43] (p. 451). The primary target of Lefebvre’s critique is the rationalist color given to the concept of urban policy by technocrats and technologists [44]; these technical experts include architects, planners, geographers, etc. Therefore, there is an imminent need to break away from the mindset of studying the design and management of space from the perspective of planners and managers and to change the concept of treating space only as a “container” to paying attention to the sociological connotation of space itself. Moreover, it emphasizes the importance of focusing on resettled villagers as active agents in understanding space production and practice, especially within urban village redevelopment.

2.2.2. Research Framework for the Adaptability of Urban Villages Based on the Dialectics of the Three Elements of Spatial Production

How is (social) space produced? The central idea of Lefebvre’s theory is that spatial production can be divided into three dialectically related dimensions or processes [42]. On the one hand, there are “spatial practices”, “representations of space”, and “spaces of representation”. On the other hand, they refer to “the perceived”, “the conceived”, and “the lived” spaces. These concatenated sequences point to a dual approach in spatial studies: one phenomenological and the other linguistic or semiotic. The three dimensions of spatial production must be understood as fundamentally equivalent [14]. Space is simultaneously perceived, conceived, and lived, and no one dimension has priority.

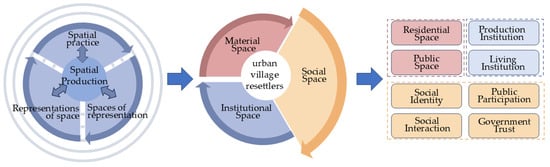

Based on the theory of spatial production, which emphasizes human agency and the spatial triad dialectics, this study proposes a theoretical analytical framework centered on resettled residents (Figure 1). This framework aims to provide methodological support for research on the adaptability of urban village redevelopment while translating and projecting the theory of spatial production into the field of urban planning. The framework comprises three core dimensions—material space, institutional space, and social space. These three dimensions are further delineated by 24 influencing factors (Table 1). Specifically, the dimension of “material space” (perceived dimension) is assessed through residents’ satisfaction with the infrastructure, public facilities, and housing conditions. The “institutional space” (conceived dimension) is measured by residents’ evaluations of the employment changes, income stability, property management satisfaction, and policy compensation during the resettlement period. The “social space” (lived dimension) is operationalized through indicators such as the neighborhood relationships, community participation, household registration preferences, and self-identity changes. This framework underscores the subjective experiences of resettled individuals and their multidimensional adaptation process, which supplements the existing literature and establishes a foundation for future empirical research and evidence-based policy formulation in diverse sociocultural contexts. By meticulously categorizing the adaptation of resettled populations, the system can devise more targeted and efficacious management strategies for urban village renovation, ultimately improving project outcomes.

Figure 1.

A ternary analytical framework for the spatial production of resettlers during adaptation to urban village transformation.

Table 1.

Evaluation indicators and interpretation of resettled residents’ adaptation in urban villages.

Firstly, in the dimension of material space, social space appears as a chain and network of activities and interactions, which in turn depend on a defined material basis (morphology, built environment) [14], mainly including the spatial form, structure, and function of the transformed urban village, etc. The adaptability of material space reflects the foundational capacity of resettled villagers to establish themselves within the transformed urban living environment. Secondly, in the dimension of institutional space, this representation constitutes an organizational model or reference framework for communication that enables (spatial) positioning and co-determines activities [14]. Various types of systems and policies produce an effective influence through policies, systems, and planning [37]; the institutional space reflects the degree of institutional security of the resettled people’s adaptation to urban life. The third dimension of spatial production is social space, which is the living experience of space. It refers to the world experienced by individuals through everyday practices [14]. The social space reflects the lifestyles, social relations, and values among social groups in villages [45], formed by different production subjects under interest or production relations. It is a space of village representation [46], and the social space reflects the resettled people’s sense of identity, belonging, and deeper integration into urban society.

The social change in the process of urban village resettlement can be far-reaching and long-lasting, and it is a socially systemic process. First, there will be a sudden and dramatic change in settlement patterns, with more “ground-level” rural forms being replaced by meticulously planned “high-rise” urban patterns. However, high-density gated communities have long been criticized for lacking a sense of community, increasing spatial segregation, alienating neighbors, and ignoring farmers’ habits [47]. Second, rural life is characterized by strong social networks, shared values, and frequent interactions [48]. In contrast, urban life is seen as having fewer social ties or complexities that extend beyond the immediate environment [49]. Rural–urban migrants may face a rapid transformation of their social relationships [50]. Third, strict planning and community management further limit spontaneous attempts by resettled villagers to reshape space to suit their lives [2]. Existing research suggests that community management focuses too much on organizing formal tasks rather than providing a platform for resettled families to adapt to urban life [51].

Another critical issue is identity construction, although identity issues have not received as much attention as physical–spatial adaptation and socio-spatial adaptation, as required by the Chinese government’s new urbanization strategy, which considers promoting the citizenship of the agricultural transfer population the primary task of new urbanization (State Council Circular on the Issuance of <the Five-Year Action Plan for the In-depth Implementation of the People-Centered New Urbanization Strategy> [2024] No. 17), so identity identification is crucial for the urbanization and resettlement of urban villagers. Identity encompasses an individual’s position in society, their perception of themselves, and their perception of those similar to them [52]. It is highly relevant to resettlement as it reflects a person’s perception of their role and the group they belong to [53]. As argued by Zhu et al. [54], resettlers’ psychological identity is a key issue in realizing the goals of urban village transformation. Their perceptions of their position in urban society, such as feelings of exclusion and psychological distance from urban residents, affect how they identify themselves [55]. Other studies have begun to suggest that the self-described identities of urban villagers may be complicated by urban lifestyles (hygiene practices, living habits, social mores, etc.) as well as by the retention of rural social networks and links to the rural collective economy [55,56].

The issue of resettled people’s identity also draws attention to the more significant structural dynamics that shape the resettlement experience in China. China’s household registration system divides the Chinese population into urban and rural residents, which is a much-discussed barrier to rural migrants’ access to urban benefits and rights [57,58]. Hukou policies continue to be relaxed, and public services have become more uniform, especially in small and medium-sized cities, where most rural migrants now have access to social benefits and welfare [59], but inequalities remain. A key aspect of the hukou system is land rights. In China, rural land ownership belongs to a collective, and residents with a rural hukou (including rural migrants) are part of this collective [60]. Those with a rural hukou legally have contractual and management rights over agricultural land, including the right to use homesteads, to lease management rights to other operators, and to receive compensation for land expropriation [61]. Since 2014, the reform of rural land rights and the revision of the Land Management Law have continued to progress, allowing rural migrants to retain their rural land rights when changing from an agricultural to an urban hukou. This institutional context needs to be considered when considering the adaptation of resettled people: not only do changes in settlement patterns, economic systems, and social relations matter but also access to welfare and land rights between urban and rural areas.

Building on these insights, our conceptual framework draws on Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space for a more in-depth analysis of the urban adaptation of resettled people in the context of urban village transformation. We examine the material, institutional, and social spaces of adaptation and the interrelationships between them. This allows us to move away from the simplistic narrative of rural villagers as urban citizens in the government’s urban village transformation and to explore the resettled people’s adaptation experiences in more detail.

This study emphasizes the following points. First, drawing on Lefebvre’s thought as a starting point, we incorporate his theories into contemporary research on urban village redevelopment, focusing specifically on the subjective experiences of resettlers. This stance is consistent with Lefebvre’s approach to Marxism, advocating a value shift from spatial efficiency to spatial equity. As the concept of new urbanization development takes root, the status and rights of landless peasants are valued and safeguarded, and the citizenship of urban village residents and the modernization of urban village governance are promoted. Secondly, this study strives to get rid of the misinterpretations of spatial production theory that exist in the domestic academic community, refusing to vacillate between the two poles of “political economics” and “cultural studies”. It grasps Lefebvre’s thought at a more holistic level. Third, by focusing on openness and wholeness, the transformation of urban villages should not be the end point of spatial transformation but should instead focus on the process of spatial production. This is in line with Lefebvre’s Marxist temperament of “heresy” and “openness”. Fourth, this study advocates for a methodological shift from qualitative analyses to quantitative approaches within the field of spatial production.

3. Research Methods

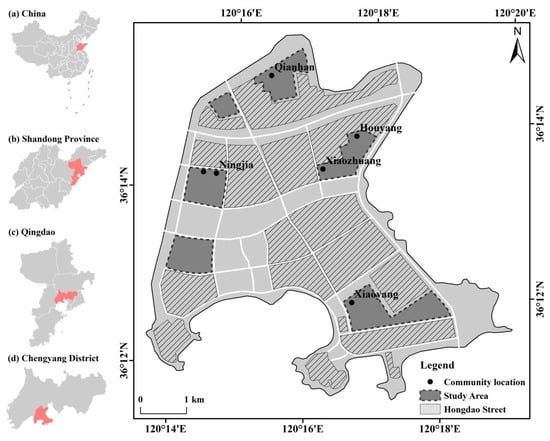

Qingdao is located on the east coast of Shandong Province, China. It surrounds Jiaozhou Bay, which contains three distinct urban areas: Qingdao Downtown in the east, Huangdao Development Zone in the west, and the urban area on the north coast (Figure 2). In 2016, the Qingdao Urban Master Plan (2011–2020) formulated the urban spatial strategy of “whole area coordination and three cities linkage”. The “three-city linkage” takes Jiaozhou Bay as the core and forms three major urban areas with complementary functions, interdependence, and distinctive features on the east, west, and north shores of Jiaozhou Bay, forming the core area of Greater Qingdao. Among these zones, The north shore urban area is the spatial hub of Qingdao’s urban–rural layout, with the government envisioning a new district emphasizing technological innovation, ecological sustainability, and cultural vitality, which is the location of the Hongdao Urban Village Resettlement Area, the case study in this study.

Figure 2.

Location of the urban village.

Under the overall development plan of Qingdao City, the local government launched the urban village transformation of Hongdao Street in 2016 and planned to relocate and resettle about 14,500 urban village residents of Hongdao Street near the village, of which 3748 households are in the southern cluster, 2943 households in the eastern cluster, 3427 households in the northern cluster, and 4382 households in the western cluster. As one of the focal points of Qingdao’s urbanization around the bay, by the end of 2024, 5704 urban village residents had been delivered, and 1945 urban village residents had been relocated and resettled.

This study uses field survey data from 256 resettled residents from five communities of Hongdao Street, and the demographic information of the survey participants is shown in Table 2. All household members living in the resettlement communities and those working as migrant workers were included in this study. A stratified random sampling method drew samples from five communities in four clusters (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Demographic information of the survey participants.

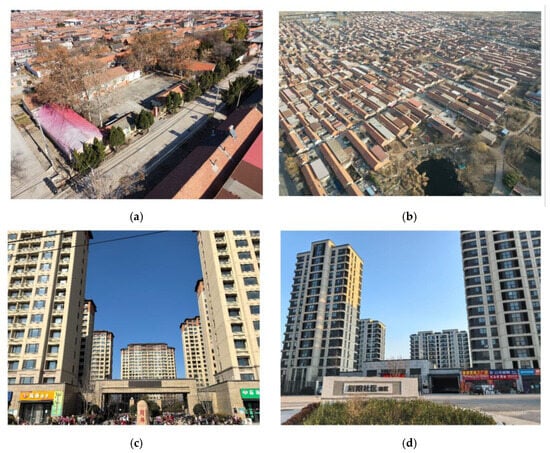

These four clusters have different regional conditions, and Figure 3 show the pre- and post-resettlement landscapes of some of these communities. From the seventeen communities in the four clusters, we selected five occupied resettlement communities in each cluster to represent different natural locations, sizes of resettlement communities, and other factors. The questionnaire included basic information about the resettled people, such as the family composition, employment patterns, housing characteristics, identity, and whether they had adapted to urban life after resettlement. We conducted a preliminary survey in mid-August 2024 and a final survey in November 2024. A total of 317 questionnaires were distributed, and 256 valid questionnaires were collected, excluding invalid questionnaires. Participants in this questionnaire survey were fully informed of the objectives of this study, the potential use of the interviews, and the results of the questionnaire survey, and they gave their explicit consent for the subsequent analysis. The combination of data from these different sources not only enriches the dynamic understanding of the adaptability of resettled people during the transformation of urban villages but also helps to promote the overall development strategy, planning and design of urban villages.

Figure 3.

(a) The pre-resettlement landscape of QianHan village; (b) the pre-resettlement landscape of Houyang village; (c) the post-resettlement landscape of the QianHan community; and (d) the post-resettlement landscape of the Houyang community.

In this study, the measurement of the questionnaire indicators adopts the Likert scale method, utilizing semantic differential scaling to classify the adaptation outcomes into five levels: Excellent, Good, Neutral, Poor, and Very Poor (corresponding to scores of 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively). In the questionnaire, respondents rate their degree of adaptation across three dimensions—material space, institutional space, and social space—on a five-point scale ranging from “very adaptable” to “very unadaptable”. Each single evaluation is expressed in five levels to facilitate the subsequent statistical analysis.

In what follows, we use the descriptive statistics from the survey to outline these three dimensions of resettlement adaptation. We begin by discussing the overall survey results and then examine specific groups in the sample in more detail to further illustrate the complexity of adaptation.

4. Analysis

4.1. Adaptation to Material Space

The core of China’s promotion of new urbanization lies in the urbanization of people, which is essentially people-oriented urbanization. It should enable villagers who have changed from “village to residence” to enjoy the same social and public services as urban residents, as well as the corresponding housing security, and to solve the problem of sharing the fruits of modernization in the city. In the redevelopment process of Hongdao’s urban villages, large-scale demolition of villages erased nearly all traces of the original rural settlements. The rebuilt resettlement communities introduced substantial changes to the villagers’ architectural structures, industrial patterns, and lifestyles. This “thorough” urbanization, characterized by reconstruction from scratch, compelled villagers to move into high-rise buildings, disrupting their previous neighborhood ties and traditional ways of living. To evaluate how the resettled residents adapted to the material space of their new environment, this study examined the suitability of the infrastructure and public service facilities in the resettlement areas. Contrary to our expectation, from the research data in this study, the resettlement residents’ adaptation to the material space of the urban village is relatively high. More than 63.67% of the resettled residents reported adapting well to moving from single-story rural houses to high-rise apartments. Although they had to give up the outdoor gray space of their rural bungalows, they had gained a quality of living that was more suitable for urban life. Furthermore, more than 64.84% of the resettlers considered that the public services, infrastructure, building quality, and environmental protection in the resettlement areas were in good condition.

The surveyed communities were equipped with relatively comprehensive infrastructure and public facilities, including public activity spaces, centralized heating, potable water and natural gas supplies, educational facilities, healthcare services, and other features characteristic of modern urban neighborhoods. Our data suggest that the transformation and upgrading of material space, which has always been a key concern in urban village transformation or urban renewal, is rated highly in the overall adaptability score and that the urban village transformation standards implemented in the Hongdao resettlement area can systematically and comprehensively improve and upgrade the human environment in urban villages, and enhance the vitality and attractiveness of the area. However, it is worth noting that only 22.27% of the resettled people think that the schools and hospitals are more convenient than in the village. The reason for this phenomenon is that, although at the policy level, the standards and control indexes for the revision and control planning and design of the renovated communities are implemented by the relevant national and local design standards, in the actual construction process, the construction of the education and medical facilities occurs later than the construction of the residential buildings. Commercial and education facilities were not delivered simultaneously after relocating the five first-delivered communities studied in this research.

4.2. Adaptation to Institutional Space

To assess the adaptation of resettled residents to institutional spaces, we focus on the resulting employment status, changes in earnings, and neighborhood council and property management. Table 3 shows the changes in employment patterns before and after resettlement. Before resettlement, the resettlers were engaged in diverse activities, and on average, the majority of their earnings already came from non-agricultural or non-fishery jobs.

Table 3.

Proportion of employment types before and after resettlement.

After resettlement, 22.7% of the resettled people continued to engage in agriculture or fishery work, and 7.4% of the resettled people lost their farming or fishing jobs due to loss of land. The proportion of resettled people engaged in non-agricultural or fishery businesses has increased, which means that after resettlement, the income composition is further skewed toward non-agricultural or non-fishery sources. However, only 1.56% of the resettled people gained employment in the service sector post-resettlement. This means that the demolition and reconstruction of urban villages in Hongdao did not seem to have resulted in stable non-agricultural employment for all resettled families.

In addition to the structural changes in income sources, we also sought to explore the situation regarding institutional space further, such as collective rental income for resettled people. In our sample, only 14.45% of resettled people reported being satisfied with the changes in collective rental income and resettlement compensation during the resettlement process. According to the survey results, most resettled people reported that the resettlement compensation and transition fees were not paid on time. Regarding the post-redevelopment collective rental income, although large commercial complexes or town centers were attached, they could not receive this part of the rent due to the construction process. Some residents reported that the increase in rental income was not noticeable or had decreased compared to before the renovation.

In addition, more than 54.3% of respondents reported positive adaptation to property management practices after moving from single-story residential communities to high-rise apartments, citing improved residential quality better suited to urban living. Over 63.28% of the resettled people expressed satisfaction with the management of the resettlement community after the resettlement and transformation because after the “village to community” transformation of Hongdao Street in 2004, the village committee was transformed into a neighborhood committee, and the staff of the neighborhood committee also came from the original village committee. Therefore, there was no change in the management of the neighborhood committee before and after the transformation. Furthermore, almost half (49.22%) of the resettled residents indicated a desire to reside in the resettlement area permanently.

4.3. Adaptation to Social Space

According to the government’s urbanization objectives, resettled villagers must assimilate into urban society and self-identify as urban residents. In the present investigation, we inquired about the respondents’ self-identity as either villagers, urban residents, or a combination of both (neither citizens nor villagers). Significantly, almost half of the resettled people (41.80%) still identified as villagers even though they now live in urban resettlement communities. About 32.42% of the resettled people perceived themselves as “marginal” or “borderline”, neither citizens nor villagers. Only 5.86% identified as citizens. In keeping with this, 93% of the respondents still retained their rural household registration hukou. In addition, about 23% of the resettled people considered their status in the current urban society low, while only 3.13% considered their social status high. These results indicate that, in spite of significant changes in their living circumstances and occupation, the transformation of self-identity progresses much more slowly, with a persistent sense of marginalization.

Our data indicate that, unlike long-range or inter-provincial relocations, Hongdao’s resettled communities have similar lifestyles and economic levels, as resettled families come from the same villages in the same areas. Consequently, they appear to have rebuilt their social networks relatively quickly: 91.41% of households reported having good relationships with their new neighbors, and 11.72% interacted most with them. These connections appear to offer significant social support to resettled families as they adapt to urban life. However, the governance in resettlement communities poses a different challenge. Community institutions are relatively weak as platforms for neighborhood relations and catalysts for local participation [2,62,63]. One way of engaging with neighbors is through involvement in community cultural activities. While 93% of households reported that the community has its activities, only 12.89% indicated frequent participation. Consequently, it can be posited that the establishment of social relationships within these communities is predominantly facilitated through individuals’ personal social activities rather than through organized community activities.

Participation in grassroots community governance is pivotal to establishing communities characterized by authentic common aspirations and a shared sense of identity [64]. The Chinese government has made it clear that resettled families have the prerogative to engage in community discourses, deliberative processes, and communal matters, such as neighborhood committee elections, neighborhood representative assemblies, and participation in government affairs within the community. Our data reveal that the majority of resettled residents were dissatisfied with their participation in the design program (78.13%) and knowledge-sharing efforts (75.78%). Only about 21.49% of resettled people were satisfied with the government’s implementation of policies and the promises made. In comparison, just 24.22% of resettled people believed that the community openly disseminates information regarding public issues. The level of community participation among resettled families was less than ideal, appearing to be largely unidirectional information reception rather than active citizen participation in community affairs.

4.4. Analysis of Differences and Correlations

4.4.1. Analysis of Differences

As previously mentioned, villagers generally lose their original socio-ecological environment following urban village resettlement. This results in significant changes to their living environment and social relations, which impacts and oscillates between various aspects of villagers’ lives, including employment, physical and mental health, and emotional well-being. Rather than focusing on a single moment of resettlement, it is imperative to emphasize the need for continuous attention to post-resettlement adaptation [63,65]. The level of adaptation exhibited by villagers after resettlement provides valuable insights into this dynamic process. In this section, this study quantifies the scores assigned to the resettled individuals’ assessments. First, before conducting the analysis of variance, the one-sample t-test function of the SPSS software is utilized to calculate the composite scores for the overall adaptation and the adaptation evaluations of the dimensions of material space, institutional space, and social space, respectively. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Current status analysis of adaptability.

The analysis results indicate that the mean scores of the three dimensions of material space, institutional space, and overall adaptation after the transformation of urban villages are 3.50, 3.36, and 3.22, respectively, which are significantly higher than the neutral score of 3, implying that the resettled residents in this research have a positive perception of the current situation of the material space, institutional space, and overall adaptation. However, the mean score for the social space dimension is 2.87, which is significantly lower than the neutral score of 3. This finding suggests that the resettled population has a negative perception toward the transformation of social space, implying that adaptation to the new urban environment may vary across dimensions. Specifically, the social space transformation may be a weak point compared to the material space and institutional space dimensions.

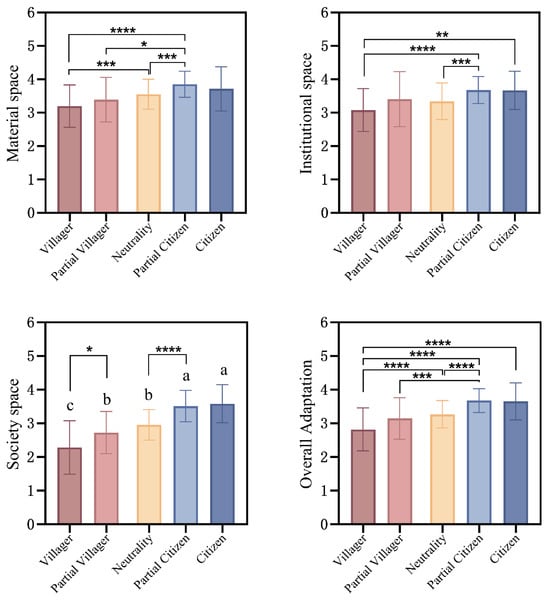

Secondly, we explore how the resettled people’s situation that may affect the adaptation situation through variance analysis (Table 5), classifying the resettled people into five groups based on their self-identified status after resettlement: those identifying as villager (77 participants), those with a partial villager identity (30 participants), those identifying as neither villager nor urban citizen (83 participants), those with a partial urban citizen identity (51 participants), and those identifying as urban citizen (15 participants). This initial classification reveals that the identity transformation intended by the resettlement process is neither uniform nor immediate: behind the survey averages, some of the resettled individuals identify as remaining villagers after the urban village resettlement, while others consider themselves urban citizens. In the following analysis, we describe the characteristics of these groups in order to explore and examine their adaptation dynamism.

Table 5.

Basic information on the five groups.

Table 3 details the fundamental family information in the present study, underscoring notable distinctions among the groups. Residents identifying as villagers after resettlement have the highest proportion of residence periods of 30 years or more, and they also have a higher proportion of groups with primary school education and below than the other groups. Compared with this, the largest proportion of resettled individuals identifying as urban citizens are aged 46 and above. Across all the groups, the proportions of those involved in agriculture and fisheries are relatively consistent, with the exception of the urban citizen group, which shows a lower proportion. These findings suggest that factors such as age, length of residence, educational attainment, and employment status may influence the identity status of resettled populations post-resettlement.

In order to enhance comprehension of the post-resettlement adaptation in Hongdao’s urban villages, this study places greater emphasis on the situation of each group according to the identity, as the adaptation assessment of these five subgroups more accurately reflects the expectations of resettled people in relation to the “city”. Table 6 presents the one-way ANOVA employed to compare the differences between the five groups of resettled people with different identities in the dimensions of material space, institutional space, social space, and overall level of adaptation, and the statistical results are as follows.

Table 6.

Analysis of identity differences.

As illustrated by the above table, statistically significant differences exist across all the dimensions of adaptability and overall adaptability among the groups, with all the p-values from the one-way ANOVA falling below 0.05. Furthermore, the results of Tamhane’s post hoc multiple comparisons further reveal that in the weakest dimension—social space adaptability—the adaptation scores increase progressively across the five groups, from villagers to urban citizens (Figure 4). In our sample,100% of resettled individuals who identified as “citizens” expressed satisfaction with the overall adaptation process. Meanwhile, 63.33% of those who described themselves as “partial villagers” and 31.17% of “villagers” reported satisfaction. This suggests a correlation between higher adaptability and urban citizen identity. At the same time, negative perceptions of resettlement—such as dissatisfaction with delayed transitional payments and lack of government transparency—are associated with a villager identity.

Figure 4.

The differences in the material space, institutional space, and social space dimensions, and the overall adaptability, among five groups with different identity recognition statuses were analyzed using Tamhane’s post hoc multiple comparisons.

Regarding their future intentions, partial villagers are more inclined to indicate a preference for permanent residence in the novel community: 70% versus 66.66% (partial citizens), 66.26% (neutral), 40% (citizens), and 33.77% (villagers). However, only 7% of households have relinquished their rural hukou, and the overwhelming majority exhibited an unwillingness to alter their hukou status. Consequently, irrespective of their prospective aspirations, most resettled households maintain their rural hukou, a phenomenon that merits further investigation.

The findings of this study demonstrate that rural land ownership provides sustained income security for resettled households, underscoring that a rural Hukou generates annual gains of approximately CNY 1200 per capita annually. Moreover, it is evident that a significant proportion of households still depend on at least a portion of their earnings from agriculture, despite the modest nature of agricultural incomes. The primary reasons given by resettled individuals who did not change their rural hukou were rooted in concerns over the potential loss of rent from collective land leases, emotional attachment to the land, and the belief that changing their hukou would not make a significant difference. This finding underscores the prevailing strong attachment to farmland among resettled households, which was identified as a salient factor in previous studies [66]. Indeed, the majority of resettled residents in this study continue to strategically “float” between urban and rural areas, relying on agricultural and non-agricultural sources of income while enjoying the benefits of improved urban amenities and the inherent security of rural land tenure.

4.4.2. Analysis of Correlations

The Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between the material space, institutional space, social space, and overall adaptability. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Pearson correlation analysis of the overall adaptation and three dimensions.

From the perspective of the adaptation effectiveness of the Hongdao urban village resettlement, the three dimensions—material space, institutional space, and social space—exhibit a significant positive correlation with overall adaptation. The significance level (P) of all the correlation coefficients is less than 0.01, and all the correlation coefficients are greater than 0. This indicates that strengthening the currently weaker dimension of social space will strongly enhance the overall adaptation of resettled residents.

Due to the government’s misperception of urban villages, the redevelopment process has been primarily focused on the outright elimination of their spatial morphology. However, our survey data suggest that urban village resettlement should ensure the simultaneous upgrading of resettled residents along with the material space, institutional space, and social space. The outcome of resettlement should be the synchronized urbanization of resettled residents and these three dimensions. Furthermore, combined with the findings in Section 4.4.1, there is a correlation between high adaptability and urban residents’ identity. Future research should focus on the negative perceptions of urban village redevelopment among resettled residents who still identify as villagers, emphasizing the development of transitional policies that facilitate their transformation from villagers to urban citizens.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Theoretical Contributions

Utilizing the three-dimensionality of Lefebvre’s theory of the production of space, our conceptual framework concentrates on three dimensions of the adaptation process of resettled people following the transformation of urban villages: material space, institutional space, and social space. At the same time, through the quantitative analysis of 24 adaptability factors in three categories, this study provides a detailed theoretical framework for the adaptability of urban village renovation with resettlement residents as the main body. The theoretical framework we establish reveals that urban village renovation is not just a simple project of “erasing urban village space” but a complex interaction of social, economic, environmental and political factors.

The findings align with and expand upon previous research in several aspects. The social space of government decision-making, credibility and communication is identified as a weak link, which is consistent with previous research results discussing the role of political governance and communication in influencing residents’ post-resettlement evaluation [12]. Based on the construction of a more complete and comprehensive development policy, it provides scientific support for the implementation of urbanization and urban–rural coordinated development strategies, which is consistent with the previous research results discussing urban–rural integration [4]. This study quantified the correlation between the three dimensions of adaptability and the overall adaptability. Although some studies have used the spatial production perspective to analyze topics such as urban village renovation [67,68], this study extends this methodology to quantitative analysis.

5.2. Discussion on the Study of Urban Village Resettlement with Resettled Residents as the Main Body

In our sample, the material space dimension is better adapted because the previous transformation of urban villages mainly manifested in the reconstruction of the landscape environment of urban villages [69]. Regarding the material space transformation, the current urban village transformation has accumulated systematic experience. The urban village transformation of Hongdao has determined different planning structures according to the level of urban economic development, the scale of the project, the villagers’ living habits, and the production organization forms to realize the material basis for a smooth transition from village to city in Hongdao. However, it should be noted that it may be necessary not only to plan public service facilities at the design stage but also to focus on the simultaneous delivery of public service facilities and residential units and to focus on interfacing with various types of public service facilities in the city in order to enable resettled people to integrate into city life positively and effectively through adequate social security facilities for commerce, healthcare, entertainment, and leisure.

Evidence suggests that resettled families have adapted positively to the institutional space, as resettlement in the vicinity of the original village site has been shown to minimize the creation of significant social or cultural differences [63]. The “village to residence” structure transformed well in advance of the resettlement of urban villages, with relatives and friends in the new neighborhoods providing support for the resettlers’ integration into urban life. Gradually, people were able to establish their own social networks. However, due to the limited absorptive capacity of industry and urban social services in the city, resettled families maintained agricultural livelihoods to support their urban life [70]. Despite some government assistance, stable non-agricultural employment for all resettled households remains elusive. The analysis further delineates a range of observed trajectories. These include a shift toward migrant labor work, small business ventures, and minimal change in employment patterns. These observations are consistent with those reported in relation to other resettlement programs in China [71,72]. In the present study’s sample, there was a paucity of skills training provided to resettlers, and a negligible number found employment through this process. Furthermore, the untimely disbursement of collective rental proceeds, transition or compensation payments, and so forth is a significant factor contributing to the reduced adaptation of resettled individuals.

With regard to the social space dimension, the overall findings of our sample demonstrate that the social space dimension is the sole dimension of dissatisfaction among the dimensions. Furthermore, our findings call into question the transparency of decision-making by government agencies and the community participation of resettled people in the current resettlement process. The findings indicate a paucity of awareness and participation of resettlers in formal community governance structures (neighborhood committees), and the majority of the sample’s perception of the low commitment and transparency of decision-making by government agencies suggests limited avenues for them to exercise their rights as community members. Concurrently, community governance systems may exhibit a paucity of formal institutional structures, particularly in the transitional communities of urban and rural migrants [73]. Recent academic research on resettlement in China has explored community governance [2]. The results of a questionnaire survey on public participation indicate that in the transformation of Hongdao urban villages, villagers adopt a passive role in the transformation process, with limited active participation. This passive participation can be considered as a “passive” process participation rather than a decision-making “active” participation. The government’s role in this process is threefold: first, to prepare transformation plans and formulate policies and standards; second, to supervise the transformation process under the law; and third, to effectively coordinate the contradictions and conflicts of the participants. The government must also play a dominant role in the directions and results of the transformation. However, it is crucial to emphasize that achieving a comprehensive understanding of the transformation process, as opposed to a simplistic approach of merely “eliminating the spatial form of urban villages”, is essential for effectively addressing the challenges posed by urban villages [74]. In this regard, the government’s promotion of urban village transformation must be underpinned by a genuine integration of the concept of “people-oriented” development into the broader framework of new urbanization and realize the citizenship of urban villagers through the transformation process, thereby ensuring that the transformation process becomes a process that comprehensively benefits all interest groups in society.

Finally, the present study found a correlation between the high level of resettlement, people’s adaptation, and urban residents’ identity. It is therefore important to ascertain whether people think their citizenship has substantially changed. A salient factor that eludes the majority’s consideration is whether individuals perceive themselves as urban residents. In relation to identity-related adaptation, there is a paucity of research exploring how individuals perceive themselves after resettlement. Our findings revealed minimal changes in self-identification, with the majority of resettled individuals still identifying as villagers or marginalized, contradicting the government’s discourse on urbanization. This study found that self-identification as villagers or marginalized is influenced by a combination of institutional factors, the community identity, and the social standing of rural immigrants as delineated by their encounters in the urban environment. This finding underscores the need for further investigation into these dynamics, as the uncertain and unstable nature of the identity of these resettlers may further facilitate their transition between rural and urban areas. The findings of this study illuminate the intricacies of the imagined transition from rural to urban life. The issue of rural–urban migration remains salient, with the majority of households in the study sample expressing a preference for permanent residence in the resettled neighborhoods and the utilization of existing public services. However, there is reluctance to alter their current hukou status. Land, while not necessarily a significant source of wealth, is nevertheless regarded as a “guarantee” of household survival and livelihood, although the situation may evolve significantly within five to ten years following resettlement. However, in the proximate phase of urban village transformation, most resettled residents are neither entirely rural nor fully urban.

The material, institutional, and socially relevant complexities involved in adaptation are all closely related to the specific institutional context of China, especially the rights and benefits associated with household registration. Furthermore, the level of villagers’ participation in the resettlement process or the openness of the government to communication is another important factor to be emphasized. The physical task of urban village demolition and relocation has been accomplished, and the goal of villager resettlement has been achieved. However, the long-term viability of these accomplishments is now contingent on addressing the systemic factors that perpetuate social exclusion, including the inadequate provision of public services, limited social engagement, and competitive resource scarcity [65,75], which continue to affect the lives of resettled populations. Future research should focus on the dynamics of these vulnerabilities and recognize the specific developmental trajectories of resettled people with different identities.

5.3. Theoretical Support of the Spatial Triadic Dialectic

The adaptability framework proposed in this study is based on empirical research results and the existing literature. Synthesizing the three dimensions of resettlement in urban villages and taking into account the particular institutional context of China’s urban-rural dichotomy, our analysis provides a more intricate picture of resettlement in urban villages. Contrary to the government’s assertion, resettlement in urban villages is not simply a wholesale shift from “agricultural” to “non-agricultural“ or from “rural” to “urban“ populations. According to Lefebvre, urban policymakers frequently overlook these processes’ profound social and spatial interconnections. He writes, “Blindness consists in the fact that we do not see the shape of the city, the vectors and tensions inherent in this sphere, its logical and dialectical movements, its intrinsic needs. We see only things, operations, objects” [42].

Lefebvre’s deconstruction of spatial epistemology underscores the contemporary inclination to conceptualize space as homogeneous and non-dialectical, devoid of social processes or politics. Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production diverts our focus from the perceived certainty of urban spaces, redirecting our attention toward the practices that sustain them. The analysis provided by Lefebvre offers a valuable point of departure for a systematic review and categorization of the numerous challenges encountered in the transformation of urban villages. It calls for a shift in perspective, moving beyond the conventional focus on the design and management of space by planners and managers. Instead, it highlights the importance of exploring the spatial production of rural resettlement subjects. Applying this approach may also create opportunities for the renewal of spatial practices and politics, as well as a more democratic vision of urban transformation.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

By integrating these factors, our analysis provides important insights into the dynamics of resettled people’s adaptation during the transformation of urban villages in China’s new urbanization process. However, this study’s contributions to understanding adaptability in the resettlement process of urban villages should be considered alongside its methodological limitations and opportunities for advancement. A key limitation of this study is its methodology. The present study is based on a large-scale questionnaire survey, a standard methodology in urban village studies (see, for example, Wang [12] and Zhang et al. [76]). However, issues such as identity, the politics of domicile, uneven access to employment opportunities, and low participation in community governance require a more detailed quantitative approach. At the same time, the reliance on a case base limited to Chinese projects, while providing insights into one cultural context, may affect the generalizability of the findings to other cultural and political contexts.

Several challenges in the adaptive strategies of resettled residents in urban village renovation point to future research directions. It is recommended that future research on urban villages adopt a more inclusive approach, engaging directly with the resettled communities to gain a deeper understanding of their individual-level adaptations, shifts in identity, mobility patterns between villages and communities, and experiences of new forms of work, and provide more opportunities for those in marginal spaces to speak out. In addition, the case base can be expanded to include urban renewal migration projects in different countries. This cross-cultural analysis can highlight regional differences, thereby improving the global applicability of research results while addressing the limitations of the comprehensiveness of current data.

6. Conclusions

This study promotes understanding of the complexity of adaptation in the process of urban village transformation by analyzing the adaptability of resettled residents. Based on the perspective of spatial production theory, this study makes the following contributions:

- It seeks to incorporate Lefebvre’s theoretical framework into empirical studies of urban village redevelopment. It emphasizes the daily practices and the subjective experiences of resettled residents as the focal point of the analysis. Based on this perspective, this study establishes a theoretical framework consisting of three major categories and 24 adaptation factors.

- For the resettled residents of Hongdao, the adaptation to the new urban environment may vary in various dimensions. Compared with the dimensions of the material space and institutional space, the transformation of the social space may be a weak link.

- There is a correlation between high adaptability and urban resident identity, while negative views on the adaptation of urban village transformation are related to a “villager” identity.

- The three dimensions of the material space, institutional space, and social space all show a significant positive correlation with the overall adaptability.

These findings provide theoretical insights and practical guidance for the governance of urban village renovation projects.

In summary, this study combines the academic research on Lefebvre’s spatial production theory with the practical application of urban village renovation, providing tools for addressing the challenges of urban village renovation in the process of new urbanization, and laying a foundation for understanding the urban phenomenon of rural farmers turning into urban citizens and formulating management strategies in urban village renovation.

The present analysis poses questions regarding the efficacy of state-led resettlement schemes in urban villages under the auspices of new urbanization in successfully producing urban citizens. These projects, characterized by their substantial capital investment, are meticulously planned to address the shortcomings of previous resettlement initiatives. By offering adequate housing and infrastructure, along with post-resettlement livelihood support, these projects aim to foster sustainable development [77,78,79]. Nevertheless, these projects continue to encounter challenges, as evidenced by the adaptation dynamics observed in the Hongdao resettlement areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.Z. and A.Z.; methodology, A.Z. and T.Z.; software, A.Z.; validation, A.Z., T.Z. and H.F.; formal analysis, A.Z.; investigation, A.Z.; resources, T.Z.; data curation, A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.Z. and T.Z.; visualization, A.Z.; supervision, T.Z.; project administration, T.Z.; funding acquisition, T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of Qingdao, China (Grant No. 23-21-1-231-zyyd-jch).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to the rural villagers and visitors who generously participated in this study and shared their valuable knowledge and experiences. Without their cooperation and involvement, this research would not have been possible. We also extend our thanks to our academic advisors and colleagues for their guidance and support throughout the research process. Finally, we express heartfelt gratitude for the generous support provided by the funders.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Qian, Z.; Xue, J.H. Small town urbanization in Western China: Villager resettlement and integration in Xi’an. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Qian, Z. Urbanization through resettlement and the production of space in Hangzhou’s concentrated resettlement communities. Cities 2022, 129, 103846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.Z.; Zhao, W. City village in dual-system emenvironment: Development and significance. Plan. Stud. 2007, 1, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.H.L.; Li, M.; Bin, J.Y.; Zhou, G.H.; Zhou, C.L. Progress and prospect on spatial organization of urban-ruralintegration in China since 2006. Prog. Geogr. 2017, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Zhang, W. Theoretical Framework of Rural-Urban Spatial Integration for County in a Metropolitan Area. Mod. Urban Res. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Z.; Ye, Y.M. Forty years of urban village redevelopment and governance: Evolution and prospect of academic thoughts. City Plan. Rev. 2022, 46, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Ma, M.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.J. Comparison and Exploration of Urban Village Renovation Models from a Flexible Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Hefei, China, 7–9 September 2024; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.Q.; Li, Z.G. Citizenization of native villagers after redeveloped urban village: A case study of liede community, Guangzhou. City Plan. Rev. 2012, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.L. Research on the Mechanism of Benefit Distribution in the Reconstruction of the Villages in Zhengzhou. Master’s Thesis, Henan Normal University, Zhengzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Zhu, Z.H.; Yang, C.; Lv, Q.; Tao, D.K. Effective, Usable, and Available: The Dynamic Mechanism and Logical Framework of Village Planning under the Model of Good Governance: A Case Study Based on Practical Village Planning in Jiangsu. South Archit. 2024, 12, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. The Study of Urban Village Reconstruction in Villagers’ Rights and Interests. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University of Political Science and Law, Chongqing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Research on Post-Evaluation of Zhengzhou’s Urban Villages Reconstruction Based on the Perspective of Villagers. Ph.D. Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Hu, Y.; Sun, D.Q. The physical space change and social variation in urban village from the perspective of space production: A case study of jiangdong village in nanjing. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, S. Towards a Three-Dimensional Dialectic: Lefebvre’s Theory of the Production of Space. Urban Plan. Int. 2021, 36, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. To Keep “Totality” and “Openness”: An Introduction of the Special Issue”Rereading The Production of Space”. Urban Plan. Int. 2021, 36, 1–4+22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Deng, H.Y. On the Forming of Consumer Space in Modern Urban Historical & Cultural Areas—An Analysis from the Perspective of Spatial Production Theory. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 23, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Tan, L. Collaged Historical District of Ciqikou: Production of Space, De-Localization, and Living Conditions. Architect 2009, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, S.W. Producing, Duplication and Character-istics Extinction: An Analysis on the Crisis of City’s Characteristic with the Theory of “ Production of Space”. Urban Plan. Forum 2009, 04, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, K.; Xu, X.Q. Critique of Urban Space Production: A Review of the New Marxist Spatial Research Paradigm. Urban Probl. 2009, 04, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Cheng, H.Z. Dissemination of “the Production of Space” in the Context of Anglo-Saxondom and China and Its Misreading in the Fields of Chinese Urban Planning and Geography. Urban Plan. Int. 2021, 36, 23–32+41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y. Mediocrity and Miraculousness in Modernity, 1st ed.; Beijing Normal University Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2018; p. 551. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, C. Urban Migrants in Developing Nations: Patterns and Problems of Adjustment, 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P. Adaptation of young peasant workers to urban life: Discoveries from practical sociology research. Society 2006, 2, 136–209. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D.R.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K. Adaptation to environmental change: Contributions of a resilience framework. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2007, 32, 395–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, W.; Ward, C. The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 1990, 14, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.; Kennedy, A. Where’s the culture in cross-cultural transition—Comparative studies of sojourner adjustment. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1993, 24, 221–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, C.S.; Jin, W.F. Integration of migrant workers: Differentiation among three rural migrant enclaves in Shenzhen. Cities 2020, 96, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Resettlement and adaptation in China’s small town urbanization: Evidence from the villagers’ perspective. Habitat Int. 2017, 67, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Displaced villagers’ adaptation in concentrated resettlement community: A case study of Nanjing, China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. From Urban Society to Urban Revolution; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume Urban question: A Marxist approach. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Chapter 6: The Question of Technology; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume Marx, capital, and the madness of economic reason. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and other real-and-imagined places. Cap. Cl. 1998, 22, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Shanghai Educational Publishing House: Shang Hai, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Charnock, G. Challenging New State Spatialities: The Open Marxism of Henri Lefebvre. Antipode 2010, 42, 1279–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chai, Y.W.; Zhang, X.L. Review on studies on production of urban space. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 31, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W. Connotation, Logical System and Its Reflections of Production of Space on Chinese New Urbanization Practice. Econ. Geogr. 2014, 34, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Luo, X.L. Capital, power and space: Decoding “production of space”. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 27, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.D.; Luan, M.Q.; Gao, H.Z. Urban and Rural Spatial Development in Scenic Areas from the Perspective of Space Production:Tianmu Lake Area in Liyang City as the Case. Urban Plan. Int. 2015, 30, 95–99+118. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.F.; Cai, T.S. The Dilemma of Historic District Reconstmctin Based on the Perspective of Space Prduction:A case Study of Small Park Historic District of Shantou. Mod. Urban Res. 2016, 07, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, F.J.; Song, L. The Internal Logic of the Spatial Production of Capital and China’s Urbanization:A New Perspective Based on New Marxist Spatial Production Theory. Shanghai Econ. Res. 2017, 10, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Research on some issues of “The Production of Space”. Philos. Trends 2014, 11, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publishing: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.Y. Lefebvre: A Critical Analysis of the Modern Essence of Everyday Life. J. Luoyang Norm. Univ. 2006, 01, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravánszky, Á.; Schmid, C.; Stanek, L. Urban Revolution Now: Henri Lefebvre in Social Research and Architecture; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.X.; Qiao, J.J. Sustainable Development of Rural Tourism Community: Based on the Analysis from the Perspective of Ternary Dialectics on Production of Space. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]