Factors Influencing Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption of Thai MSMEs: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To develop an integrated DOI-RBV-TOE model for assessing MSMEs’ CBEC adoption.

- To examine the applicability of the integrated DOI-RBV-TOE model for assessing CBEC adoption in the context of manufacturing MSMEs.

- To analyze the factors influencing the adoption of CBEC among manufacturing MSMEs in Thailand using an integrated DOI-RBV-TOE model.

- To provide practical recommendations for Thai MSMEs and policymakers on transitioning from traditional trade to CBEC to enhance competitiveness and profitability in the digital economy.

2. Literature Review

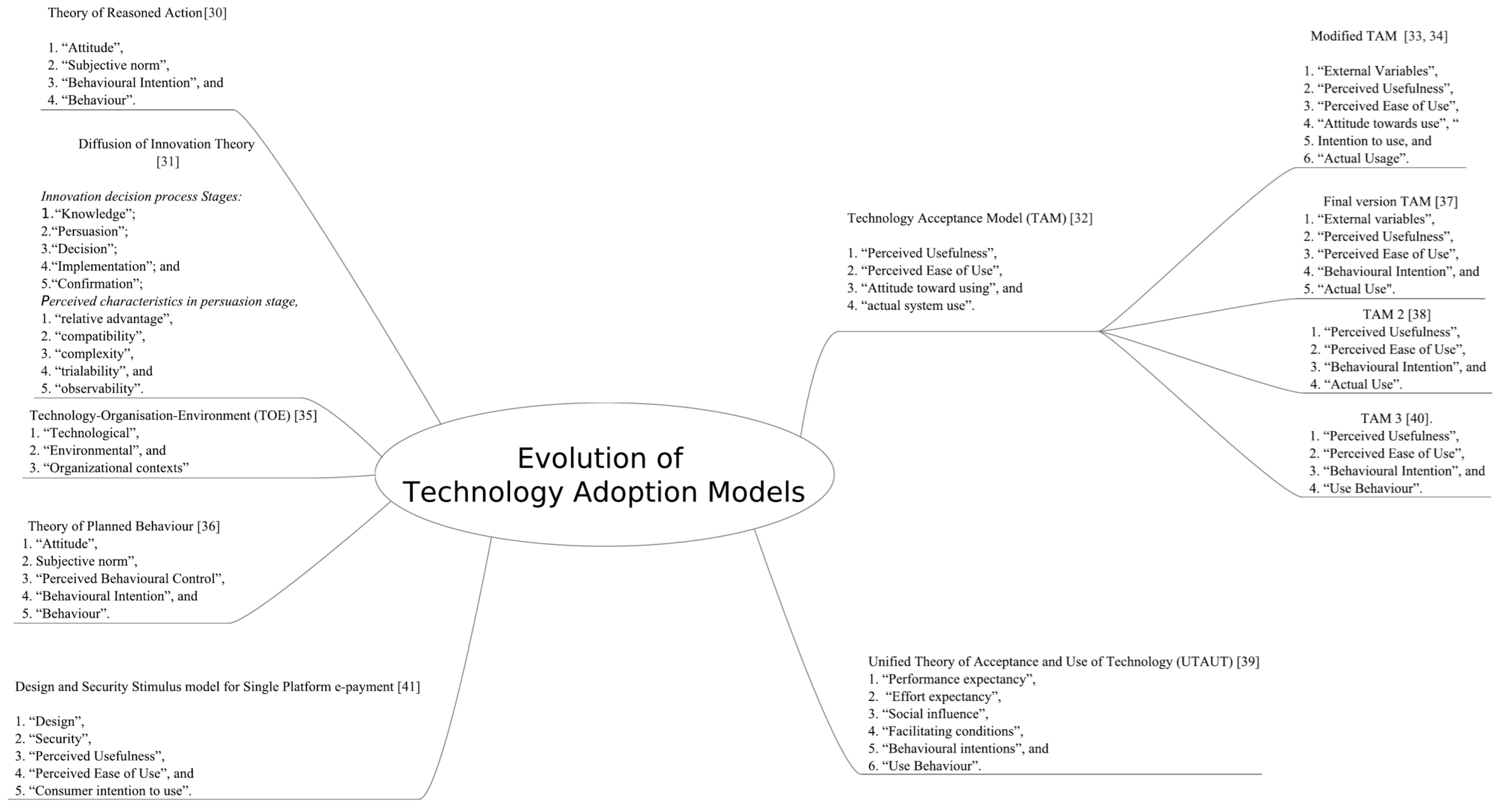

2.1. Technology Adoption Models and TOE Framework

2.2. The Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) and Resource-Based View (RBV) Theories

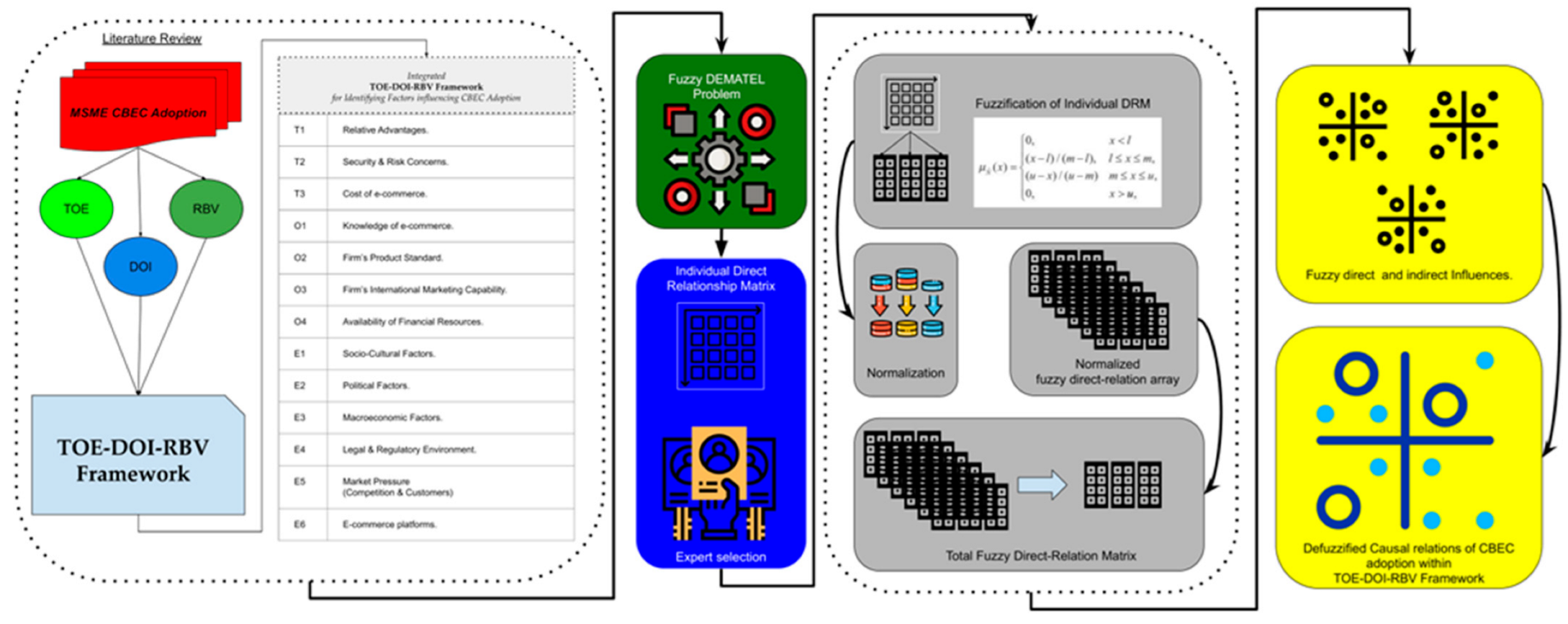

2.3. An Integrated DOI-RBV-TOE Theory for Identifying CBEC Variables

3. Methodology

- Step 1: The Statistical Tool, Construct, Scale Development and Questionnaire Format

- Step 2: Data Collection

- Step 3: Fuzzification

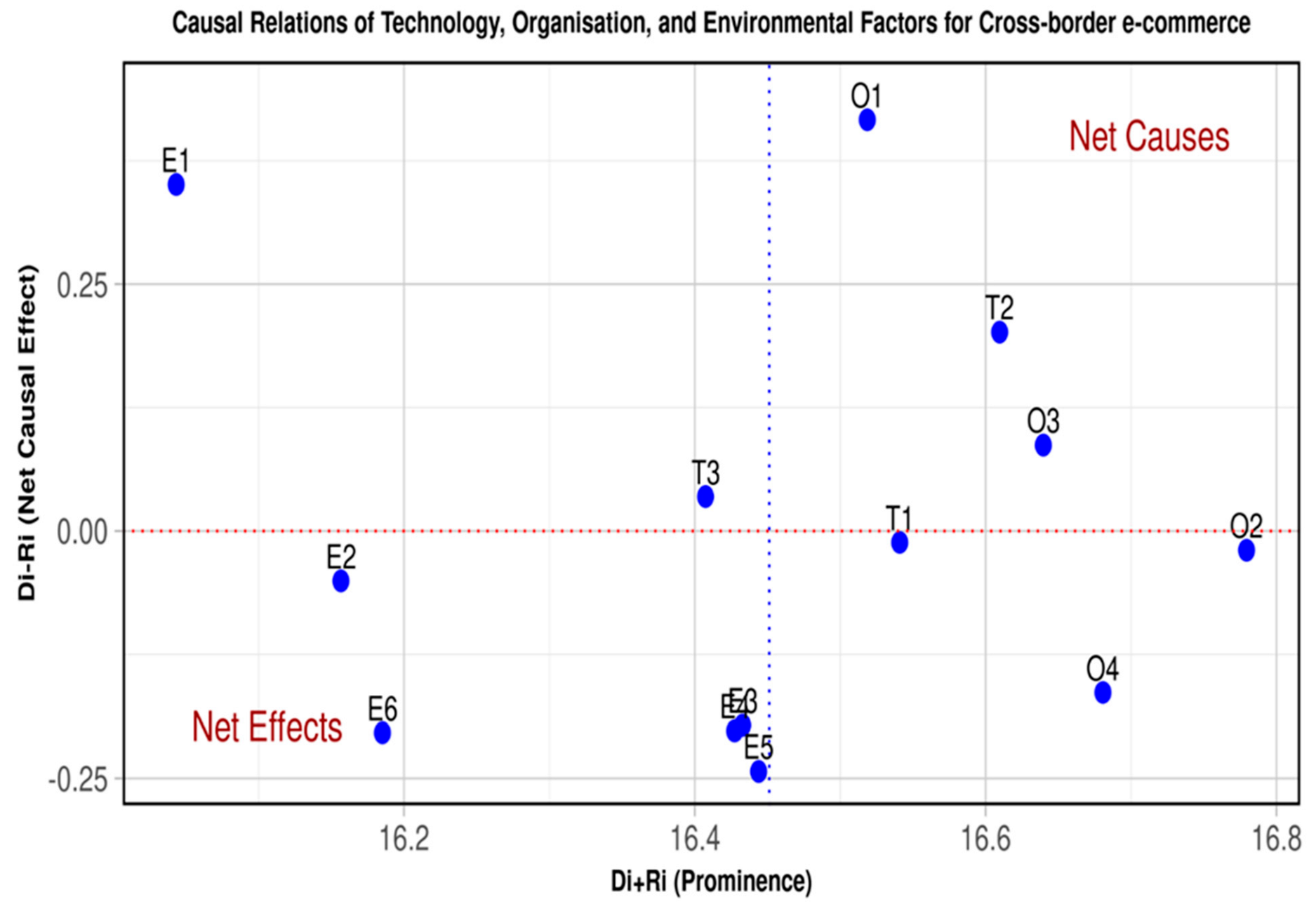

4. Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNCTAD. Global E-Commerce Hits $25.6 Trillion—Latest UNCTAD Estimates. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/global-e-commerce-hits-256-trillion-latest-unctad-estimates (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- UNCTAD. Making E-Commerce and the Digital Economy Work for All. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/making-e-commerce-and-digital-economy-work-all (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD Technical notes on ICT for development. In Business E-Commerce Sales and the Role of Online Platforms; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1, ISBN 978-92-1-106449-0. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulkarem, A.; Hou, W. The Influence of the Environment on Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption Levels Among SMEs in China: The Mediating Role of Organizational Context. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 215824402211038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thailand—eCommerce. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/thailand-ecommerce (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Sukantapong, K. Thai SMEs Interested in Doing Cross Border e-Commerce, Look This Way in Guangxi—Thaibizchina. Available online: https://thaibizchina.com/artcle/smes-%E0%B9%84%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%A2%E0%B8%AA%E0%B8%99%E0%B9%83%E0%B8%88%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B3-cross-border-e-commerce-%E0%B8%A1%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%97%E0%B8%B2%E0%B8%87%E0%B8%99%E0%B8%B5%E0%B9%89/ (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Policy and Strategy Department. Digital Economy Promotion Agency Cross-Border e-Commerce: A New Choice for Thai Entrepreneurs in the Digital World. Available online: https://www.depa.or.th/en/article-view/cross-border-e-commerce (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Department of International Trade Promotion. E-Services. 2022. Available online: https://www.ditp.go.th/e-services (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- OSMEP. Thai Trade (E-Marketplace). Available online: https://en.sme.go.th/en/page.php?modulekey=432 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Thaitrade.com. Available online: https://www.thaitrade.com/ (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Arunmas, P. Cross-Border Trade Poised to Hit B1.80tn. Bangkok Post. 5 September 2022. Available online: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/general/2384295/cross-border-trade-poised-to-hit-b1-80tn (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- The Government Public Relations Department. Thailand’s Border Trade Value Increases by 4.9% this Year. Available online: https://thailand.prd.go.th/en/content/category/detail/id/52/iid/195602 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Fan, C.; Pongpatcharatrontep, D. Kano Model for Identifying Cross-Border e-Commerce Factors to Export Thai SMEs Products to China. In Proceedings of the 2020 Joint International Conference on Digital Arts, Media and Technology with ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (ECTI DAMT & NCON), Pattaya, Thailand, 11–14 March 2020; pp. 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ractham, P.; Banomyong, R.; Sopadang, A. Two-Sided E-Market Platform: A Case Study of Cross Border E-Commerce between Thailand and China. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Electronic Business, Newcastle, UK, 8–12 December 2019; pp. 475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Siriphon, A.; Gatchalee, P.; Li, J. China’s Cross-Border E-Commerce: Opportunities and New Challenges of Thailand. Connex. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Cao, Z. An Empirical Study on the Trade Impact of Cross Border E-Commerce on ASEAN and China under the Framework of RECP. In E3S Web of Conferences, Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Economic Innovation and Low-Carbon Development (EILCD 2021), Qingdao, China, 28–30 May 2021; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2021; Volume 275, p. 01039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, Z.S. Yunnan Dunjue Company Business Development Strategy of Cross-Border E-Commerce in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Siam University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krainara, C. Cross-Border Trade and Commerce in Thailand: Policy Implications for Establishing Special Border Economic Zones. Ph.D. Thesis, Asian Institute of Technology, Bangkok, Thailand, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krainara, C.; Routray, J.K. Cross-Border Trades and Commerce between Thailand and Neighboring Countries: Policy Implications for Establishing Special Border Economic Zones. J. Borderl. Stud. 2015, 30, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Feng, Y.; Wang, W.; Qiu, M.; Yang, H. The Development Prospects of Cross-Border E-Commerce in Thailand; Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 42, pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huy, L.V.; Rowe, F.; Truex, D.; Huynh, M.Q. An Empirical Study of Determinants of E-Commerce Adoption in SMEs in Vietnam: An Economy in Transition. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 2012, 20, 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.K.; Windasari, N.A.; Pai, R. Exploring E-Readiness on E-Commerce Adoption of SMEs: Case Study South-East Asia. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Bangkok, Thailand, 10–13 December 2013; pp. 1382–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Siraj, S. A Systematic Review and Analysis of Determinants Impacting Adoption and Assimilation of E-Commerce in Small and Medium Enterprises. Int. J. Electron. Bus. 2018, 14, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornkitvikai, Y.; Tham, S.Y.; Harvie, C.; Buachoom, W.W. Barriers and Factors Affecting the E-Commerce Sustainability of Thai Micro-, Small-and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSMEs). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Z.; Samikon, S.A.; Jintao, X. Multiple Regression Analysis on the Influencing Factors in Smes Adoption of Cross-Border E-Commerce: Evidence from China. Spec. Ugdym. 2023, 1, 568–586. [Google Scholar]

- Madhavan, M.; Sharafuddin, M.A.; Wangtueai, S. Impact of Industry 5.0 Readiness on Sustainable Business Growth of Marine Food Processing SMEs in Thailand. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, V.; Ahmi, A.; Saad, R.A.J. E-Commerce Adoption Research: A Review of Literature. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2018, 6, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Patel, A.N.; Shaikh, M.Z.; Chavan, C.R. SLRA: Challenges Faced by SMEs in the Adoption of E-Commerce and Sustainability in Industry 4.0. Acta Univ. Bohem. Meridionales 2021, 24, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrezeanu, A. Models of Technology Adoption: An Integrative Approach. Netw. Intell. Stud. 2015, 3, 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M.; Chakrabarti, A.K. The Processes of Technological Innovation. In Issues in Organization and Management Series; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations; The Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Model of the Antecedents of Perceived Ease of Use: Development and Test. Decis. Sci. 1996, 27, 451–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A Theoretical Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model: Four Longitudinal Field Studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.C. Design and Security Impact on Consumers’ Intention to Use Single Platform E-Payment. Interdiscip. Inf. Sci. 2016, 22, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A Resource-based View of the Firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassia, F.; Magno, F. Cross-Border e-Commerce as a Foreign Market Entry Mode among SMEs: The Relationship between Export Capabilities and Performance. Rev. Int. Bus. Strategy 2022, 32, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Lin, Y.-C.; Bag, A.; Chen, C.-L. Influence Factors of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and Micro-Enterprises in the Cross-Border E-Commerce Platforms. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 416–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabanda, S.K.; Brown, I. E-Commerce Enablers and Barriers in Tanzanian Small and Medium Enterprises. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 67, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmawan, B.N.; Ridho, W.F. Determinants Influencing SMEs in E-Commerce Adoption through Local Government Facilities in Indonesia: Mixed Methods Approach. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 90, e12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Wei, M.; Teo, B.S.-X. Analysis of the Key Influencing Factors of China’s Cross-Border e-Commerce Ecosystem Based on the DEMATEL-ISM Method. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dou, Z.; Yang, W. Research on Influencing Factors of Cross Border E-Commerce Supply Chain Resilience Based on Integrated Fuzzy DEMATEL-ISM. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36140–36153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, R.; Standing, C. A Classification Model to Support SME E-Commerce Adoption Initiatives. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2006, 13, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.Y.; Magobe, M.J.; Kim, Y.B. E-Commerce Applications in the Tourism Industry: A Tanzania Case Study. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 46, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Qu, F.; Zhao, Y. The Influencing Factors Model of Cross-Border e-Commerce Development: A Theoretical Analysis. In Proceedings of the 17th Wuhan International Conference on E-Business—Cross-border e-Commerce Initiatives under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, WHICEB 2018, 74., Wuhan, China, 25–27 May 2018; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/whiceb2018/74/ (accessed on 29 December 2023).

- Liu, A.; Osewe, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhen, X.; Wu, Y. Cross-Border E-Commerce Development and Challenges in China: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabus, A.; Fontela, E. Perceptions of the World Problematique: Communication Procedure, Communicating with Those Bearing Collective Responsibility; Battelle Geneva Research Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.; Chang, C.-W.; Wu, C.-H. Fuzzy DEMATEL Method for Developing Supplier Selection Criteria. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.-L.; You, X.-Y.; Liu, H.-C.; Zhang, P. DEMATEL Technique: A Systematic Review of the State-of-the-Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 3696457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.; Sharafuddin, M.A.; Wangtueai, S. Assessing Trade Attractiveness Using International Marketing Environmental Factors and Fuzzy DEMATEL. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2021, 09721509211046335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-W.; Lee, Y.-T. Developing Global Managers’ Competencies Using the Fuzzy DEMATEL Method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Herrera, E.; Martens, B.; Turlea, G. The Drivers and Impediments for Cross-Border e-Commerce in the EU. Inf. Econ. Policy 2014, 28, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Huo, J.; Campos, J.K. The Development of Cross Border E-Commerce. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Transformations and Innovations in Management (ICTIM 2017), Shanghai, China, 9–10 September 2017; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 487–500. [Google Scholar]

- Valarezo, Á.; Pérez-Amaral, T.; Garín-Muñoz, T.; García, I.H.; López, R. Drivers and Barriers to Cross-Border e-Commerce: Evidence from Spanish Individual Behavior. Telecommun. Policy 2018, 42, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.No. | Factors/Variables | Study Type | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Owners and their management, industry sectors and relationships, anticipation and realization of benefits, lack of knowledge, lack of resources, external factors, and technology factors. | Qualitative study (mixed method—literature, case studies, stakeholder participation, and seminars) | [50] |

| 2 | TOE framework (Characteristics of technology (relative advantage, perceived compatibility, complexity and innovation risk), organization (resources such as HR, financial, technology, and knowledge), environment (government incentives and support, industry support, intensity of competition, and buyer and supplier behavior), and managers (attitude, and new knowledge of IT)). | Quantitative study (logistic regression) | [21] |

| 3 | Technology, organization, environment, and management (internal). | Quantitative study (AHP) | [22] |

| 4 | Intensity of pressure, perceived benefits, technological competence, and barriers to e-commerce use. | Quantitative study (used SEM tools) | [51] |

| 5 | Perceived organizational factors (awareness, management support, human resources, lack of ICT expertise, technology resources, governance, business resources, and mobile phone tech) and perceived environmental factors (lack of market e-readiness, lack of institutional e-readiness, lack of industrial support, and socio-cultural norms). | Qualitative research (thematic analysis) | [46] |

| 6 | In the context of technology (relative advantage, compatibility, technology cost, security, and risk), organization (technology readiness, strategic orientation, and firm characteristics), environmental (external pressure, government support, support from technology supplier), and individual (innovativeness of the owner, characteristics, experience, and top management support). | Review and systematic qualitative approach for grouping variables and clustering factors | [23] |

| 7 | Country infrastructure, technology infrastructure, management support, Diffusion of Innovation theory factors, environmental factors (external pressures from stakeholders – competitor, supplier, customer, government, industry), organizational readiness, IT skills, and capabilities. | Literature review | [27] |

| 8 | Political, economic, social, and technology (PEST) from a macroeconomic perspective along with the stakeholders of CBEC. | Review | [52] |

| 9 | Information flow, financial flow, and logistics flow. | Quantitative research (Kano Model) | [13] |

| 10 | Resource-Based View (RBV) (capabilities and resources), Diffusion of Innovation (innovation characteristics and IT), and TOE (cost, top management support, government support, and competitive pressure). | Review analysis | [28] |

| 11 | Regulatory support, competitor pressure, and the IT infrastructure. | Quantitative research (PLS-SEM) | [47] |

| 12 | The study conceptualized and assessed the links between export capabilities (IT, international marketing, export operations) and CBEC’s strategic and financial performance. | Quantitative research (PLS-SEM) | [44] |

| 13 | Customs clearance efficiency, logistics costs and risks, customs declaration and tax refunds, payment risks, and management and talents. | Systematic literature review | [53] |

| 14 | Technological factors (internal e-commerce tools such as websites, smartphones, and PCs), organizational factors (owner characteristics such as age, gender, education, and IT skills), firm characteristics (firm size, age, e-commerce experience), and external environment (external e-commerce platforms). | Quantitative research technique (used the Tobit regression model and one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test) | [24] |

| 15 | TOE—technology (perceived relative advantage, cost, complexity, and compatibility), organization (top management support, technology resources, human resources, firm size, level of decentralization and formalization), and environmental factors (pressure from competitors, suppliers, and customers, regulatory and legal environment in home and host country, and e-readiness of the home and host country). | Quantitative research (SEM using SmartPLS 3 software) | [4] |

| 16 | TOE—technology (level), organization (resources, internationalization level), and environment (pressure of competition and policy support). | Quantitative study (linear regression) | [25] |

| 17 | Internal enterprise factors (e-commerce platforms, e-commerce logistics, foreign trade, payment security, certification, and cooperation among firms), government support (subsidies, tax incentives, infrastructure investment, degree of supervision), economic foundation (GDP, standard of living, per capita income), and external environment (culture, demand, competitiveness, scale of CBEC transactions, and investment in information technology). | Quantitative research (DEMATEL and ISM analysis) | [48] |

| 18 | Five capabilities (product, marketing, cross-border potential, knowledge, and cross-border start-up) and CBEC platforms (economic, technological, social, and legal). The study found that firms’ capabilities affect CBEC platforms. | Interviews and case study approach | [45] |

| T1 | T2 | T3 | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | NA | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| T2 | 4 | NA | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| T3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| O1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | NA | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| O2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| O3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| O4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | NA | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| E1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | NA | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| E2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| E3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | NA | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| E4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 4 | 3 |

| E5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | NA | 4 |

| E6 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | NA |

| Component 1 (l) | Component 2 (m) | Component 3 (u) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | T1 | T2 | T3 | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | T1 | T2 | T3 | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | |||

| T1 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | T1 | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | T1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| T2 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | T2 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | T2 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 |

| T3 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | T3 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | T3 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 |

| O1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | O1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | O1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O2 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | O2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | O2 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O3 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | O3 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | O3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| O4 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | O4 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | O4 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| E1 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | E1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | E1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 |

| E2 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | E2 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | E2 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 |

| E3 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | E3 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | E3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| E4 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0 | 0.25 | 0.25 | E4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | E4 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| E5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | E5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | E5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| E6 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0 | E6 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | E6 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.75 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Steps | Label | Equation | Equation Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Direct relationship matrix | (1) | |

| 2. | Fuzzification | (2) | |

| (3) | |||

| (4) | |||

| 3. | Normalization | (5) | |

| 4. | Normalized fuzzy direct relation array | (6) | |

| 5. | Compute total relationship | (7) | |

| 6. | Calculating the direct and indirect influences | (8) | |

| (9) | |||

| (10) | |||

| (11) | |||

| (12) | |||

| (13) | |||

| 7. | Defuzzification | (14) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madhavan, M.; Sharafuddin, M.A.; Wangtueai, S. Factors Influencing Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption of Thai MSMEs: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083632

Madhavan M, Sharafuddin MA, Wangtueai S. Factors Influencing Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption of Thai MSMEs: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083632

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadhavan, Meena, Mohammed Ali Sharafuddin, and Sutee Wangtueai. 2025. "Factors Influencing Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption of Thai MSMEs: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083632

APA StyleMadhavan, M., Sharafuddin, M. A., & Wangtueai, S. (2025). Factors Influencing Cross-Border E-Commerce Adoption of Thai MSMEs: A Fuzzy DEMATEL Approach. Sustainability, 17(8), 3632. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083632