How Trust Affects Hazardous Chemicals Logistics Enterprises’ Sustainable Safety Behavior: The Moderating Role of Government Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Trust in Government

2.2. Safety Behavior in HCLEs

2.3. Multifaceted Role of Government Governance in HCL

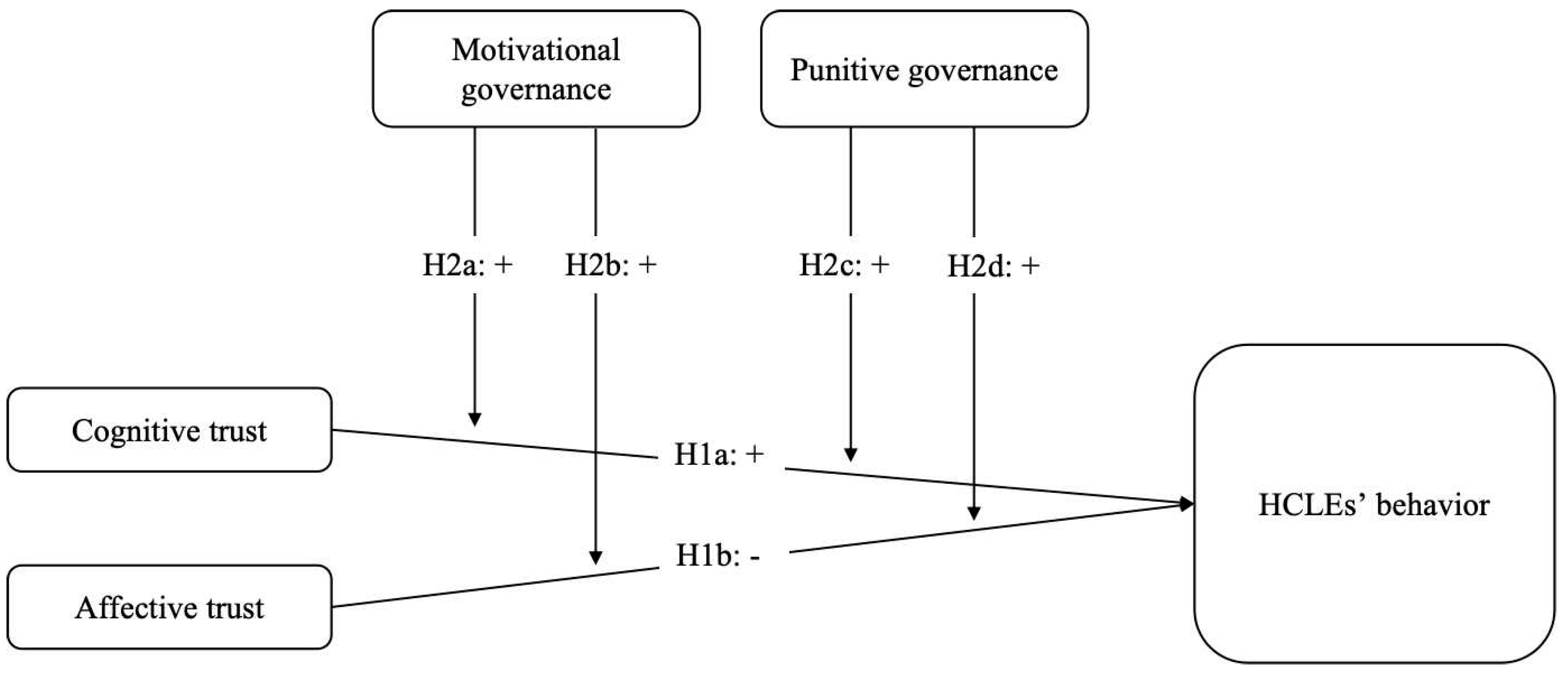

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Influence of Trust on HCLEs’ Behavior

3.2. Moderating Effect of Government Governance

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

4.2. Measures

4.2.1. Trust

4.2.2. HCLEs’ Behavior

4.2.3. Government Governance

4.3. Reliability and Validity

4.4. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.5. Correlation Analysis

4.6. Validated Factor Analysis

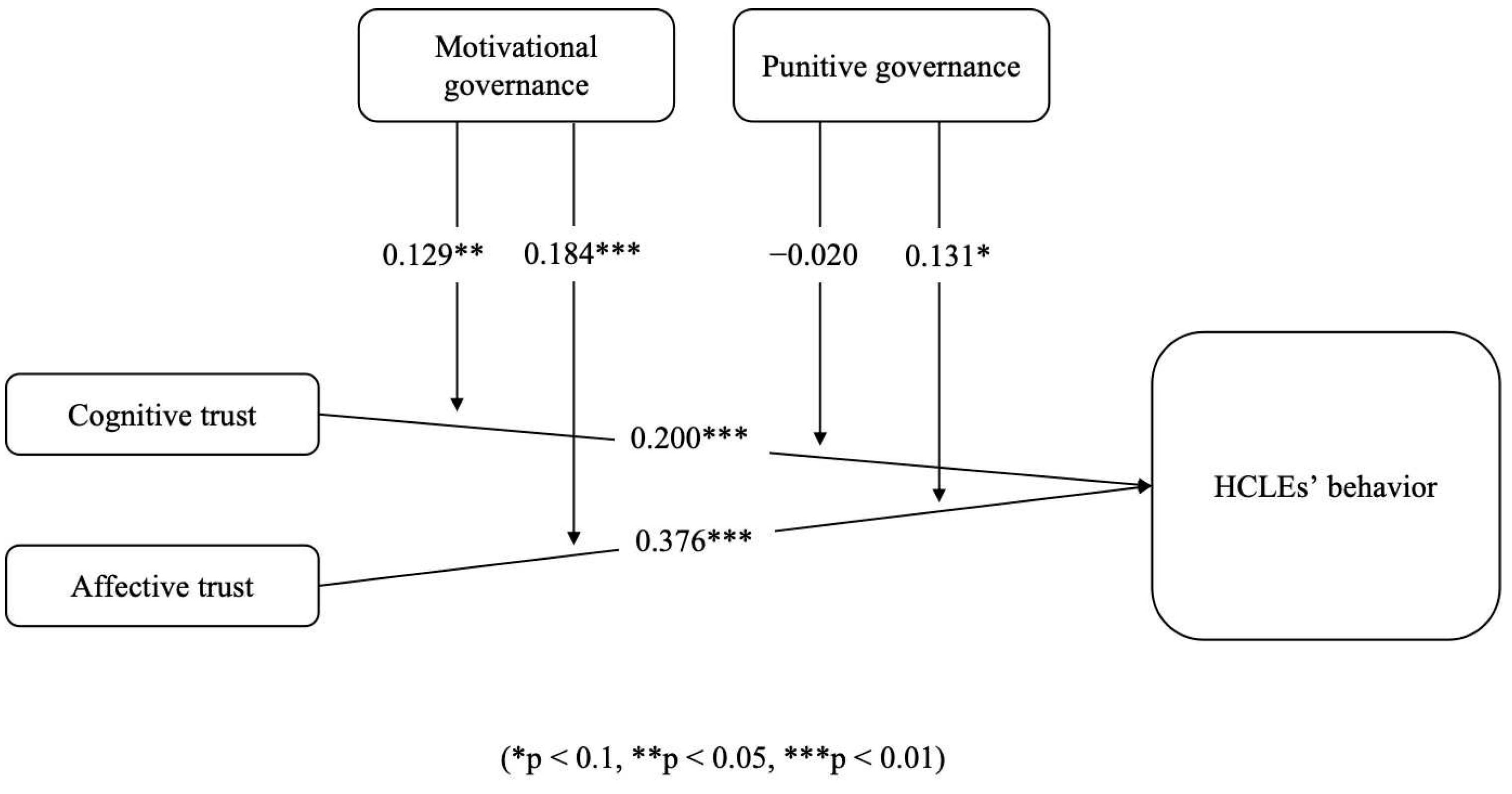

4.7. Results

5. Discussion and Implication

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCL | Hazardous Chemical Logistics |

| HCLEs | Hazardous Chemical Logistics Enterprises |

References

- Marcotte, P.; Mercier, A.; Savard, G.; Verter, V. Toll Policies for Mitigating Hazardous Materials Transport Risk. Transp. Sci. 2009, 43, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhang, D. Causation Analysis of Fire Explosion in the Port’s Hazardous Chemicals Storage Area Based on FTA-AHP. Process Saf. Prog. 2023, 42, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Fang, X.; He, J.; Huang, L. Exploiting Expert Knowledge for Assigning Firms to Industries: A Novel Deep Learning Method. MIS Q. 2022, 47, 1147–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Verreynne, M.-L.; Steen, J.; Torres De Oliveira, R. Government Support versus International Knowledge: Investigating Innovations from Emerging-Market Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Bhatnagar, S. Impact of COVID-19 on Ports, Multimodal Logistics and Transport Sector in India: Responses and Policy Imperatives. Transp. Policy 2023, 130, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stekelorum, R.; Gupta, S.; Laguir, I.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S. Pouring Cement down One of Your Oil Wells: Relationship between the Supply Chain Disruption Orientation and Performance. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 2084–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Yang, G. Research on the Tripartite Evolutionary Game of Public Participation in the Facility Location of Hazardous Materials Logistics from the Perspective of NIMBY Events. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 72, 103017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abkowitz, M.; List, G.; Radwan, A.E. Critical Issues in Safe Transport of Hazardous Materials. J. Transp. Eng. 1989, 115, 608–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousuf, R.; Majid, Z.A. Navigating the Risks: A Look at Dangerous Goods Logistics Management for Women in Logistics. In Women in Aviation; Abdul Rahman, N.A., Mohd Nur, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 161–174. ISBN 9789819930975. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.; Yu, D.; Xue, B.; Wang, X.; Jing, J.; Zhang, W. Transport Risk Modeling for Hazardous Chemical Transport Companies—A Case Study in China. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 84, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Liu, R.; Tian, M. The Bright Side of Dependence Asymmetry: Mitigating Power Use and Facilitating Relational Ties. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 251, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, B.; Haney, M.H.; Kang, M. The Effect of Buyer Digital Capability Advantage on Supplier Unethical Behavior: A Moderated Mediation Model of Relationship Transparency and Relational Capital. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 253, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowell, D.; Morrison, M.; Heffernan, T. The Changing Importance of Affective Trust and Cognitive Trust across the Relationship Lifecycle: A Study of Business-to-Business Relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 44, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K. Trust as an Affective Attitude. Ethics 1996, 107, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust as Foundations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfinch, S.; Taplin, R.; Gauld, R. Trust in Government Increased during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Australia and New Zealand. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2021, 80, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eesley, C.; Lee, Y.S. In Institutions We Trust? Trust in Government and the Allocation of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Organ. Sci. 2023, 34, 532–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, I.C.D.; Campos, E.A.R.D.; Pagani, R.N.; Guarnieri, P.; Kaviani, M.A. Are Collaboration and Trust Sources for Innovation in the Reverse Logistics? Insights from a Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 25, 176–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Singh, H.; Chaturvedi, K.R.; Rakesh, S. Blockchain in Logistics Industry: In Fizz Customer Trust or Not. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2020, 33, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.-L.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Lai, K. Linking Inter-Organizational Trust with Logistics Information Integration and Partner Cooperation under Environmental Uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 139, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, R.; Pimpohnsakun, P.; Booncharoen, P. Exploring the Impact of Logistics Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction, Trust and Loyalty in Bus Transport. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2024, 16, 519–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Cao, G.; Xing, D. Evolutionary Dynamics of the Port Hazardous Chemical Logistics Enterprises’ Security Behavior under Dynamic Punishment. J. Coast. Res. 2019, 94, SI087–SI94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yang, G.; Han, J.; Duo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Tong, R. Quantitative Assessment of Human Error of Emergency Behavior for Hazardous Chemical Spills in Chemical Parks. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 189, 930–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollnagel, E. Safety–I and Safety–II: The Past and Future of Safety Management, 1st ed.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781315607511. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Hazardous Materials Safety 2019–2020 Biennial Report; U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA): Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Abdi, A.N.M. The Mediating Role of Perceptions of Municipal Government Performance on the Relationship between Good Governance and Citizens’ Trust in Municipal Government. Glob. Public Policy Gov. 2023, 3, 309–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M. Citizens’ Trust in Government as a Function of Good Governance and Government Agency’s Provision of Quality Information on Social Media during COVID-19. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 38, 101597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, T.; Gao, W.; Xie, W.; Yu, Z. How Does Environmental Regulation Affect Real Green Technology Innovation and Strategic Green Technology Innovation? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 872, 162221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Jebran, K. Trust and Corporate Social Responsibility: From Expected Utility and Social Normative Perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chkir, I.; Rjiba, H.; Mrad, F.; Khalil, A. Trust and Corporate Social Responsibility: International Evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Piao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y. Trust and Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from CEO’s Early Experience. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 78, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1985; ISBN 9781489922731. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, T.D. The Effects of Interpersonal Trust on Work Group Performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K.G.; Carroll, S.J.; Ashford, S.J. Intra- and interorganizational cooperation: Toward a research agenda. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Waseem, D.; Xia, Z.; Tran, K.T.; Li, Y.; Yao, J. To Disclose or to Falsify: The Effects of Cognitive Trust and Affective Trust on Customer Cooperation in Contact Tracing. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 94, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.; Grayson, K. Cognitive and Affective Trust in Service Relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M. The Effects of Emotions on Trust in Human-Computer Interaction: A Survey and Prospect. Int. J. Human Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 6864–6882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacke, F.; Knockaert, M.; Patzelt, H.; Breugst, N. When Do Greedy Entrepreneurs Exhibit Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior? The Role of New Venture Team Trust. J. Manag. 2023, 49, 974–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Ma, J.; Liu, R.; Jin, W. Multi-Class Hazmat Distribution Network Design with Inventory and Superimposed Risks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 161, 102693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.G. Reinforcement Theory and the Consumer Model. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1979, 61, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villere, M.F.; Hartman, S.S. Reinforcement Theory: A Practical Tool. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 1991, 12, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.R.; Rakotonarivo, O.S.; Bhargava, A.; Duthie, A.B.; Zhang, W.; Sargent, R.; Lewis, A.R.; Kipchumba, A. Financial Incentives Often Fail to Reconcile Agricultural Productivity and Pro-Conservation Behavior. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambuehl, S. An Experimental Test of Whether Financial Incentives Constitute Undue Inducement in Decision-Making. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, R.L. Punishment. Am. Psychol. 1964, 19, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayvaci, A.S.; Cox, A.D.; Dimopoulos, A. A Quantitative Systematic Literature Review of Combination Punishment Literature: Progress Over the Last Decade. Behav. Modif. 2025, 49, 117–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stajkovic, A.D.; Luthans, F. A meta-analysis of the effects of organizational behavior modification on task performance, 1975–1995. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1122–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H. The Effects of Competitive Environment on Supply Chain Information Sharing and Performance: An Empirical Study in China. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying Careless Responses in Survey Data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutt, C.S.; Harvey, W.S.; Shaw, G. Exploring the Relevance of Social Exchange Theory in the Middle East: A Case Study of Tourism in Dubai, UAE. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 25, 198–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measures for the Safety Management of Road Transport of Dangerous Goods; Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Quackenbush, S.L. Deterrence Theory: Where Do We Stand? Rev. Int. Stud. 2011, 37, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Guo, W. Evolutionary Game and Simulation Analysis of Tripartite Subjects in Public Health Emergencies under Government Reward and Punishment Mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, N.; Manrai, A.K.; Manrai, L.A. The Financial Services Industry and Society: The Role of Incentives/Punishments, Moral Hazard, and Conflicts of Interests in the 2008 Financial Crisis. J. Econ. Finance Adm. Sci. 2017, 22, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. The Devastating Health Consequences of the Ohio Derailment: A Closer Look at the Effects of Vinyl Chloride Spill. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.W.; Dekker, H.C.; Van Den Abbeele, A. Costly Control: An Examination of the Trade-off Between Control Investments and Residual Risk in Interfirm Transactions. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 2163–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Dimoka, A. The Nature and Role of Feedback Text Comments in Online Marketplaces: Implications for Trust Building, Price Premiums, and Seller Differentiation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2006, 17, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Nawaz, M.R.; Ishaq, M.I.; Khan, M.M.; Ashraf, H.A. Social Exchange Theory: Systematic Review and Future Directions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1015921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Based on the Theory of Reinforcement Learning in Psychology. Systems 2023, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraeder, S. When Beliefs Influence the Perceived Signal Precision: The Impact of News on Reinforcement-Oriented Agents. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 5517–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, G.M.; Snyder, H.T.; de Vries, J.R.; Temby, O. On Inter-Organizational Trust, Control and Risk in Transboundary Fisheries Governance. Mar. Policy 2021, 134, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dak-Adzaklo, C.S.P.; Wong, R.M.K. Corporate Governance Reforms, Societal Trust, and Corporate Financial Policies. J. Corp. Finance 2024, 84, 102507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale Dimension | Cronbach’s α | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

|---|---|---|

| motivational governance | 0.916 | 0.895 |

| punitive governance | 0.912 | 0.834 |

| cognitive trust | 0.900 | 0.713 |

| affective trust | 0.907 | 0.696 |

| HCLEs’ behavior | 0.954 | 0.940 |

| Scale Dimensions | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| motivational governance | 3.444 | 1.195 |

| punitive governance | 3.502 | 1.189 |

| cognitive trust | 3.180 | 1.355 |

| affective trust | 2.982 | 1.325 |

| HCLEs’ behavior | 3.096 | 1.339 |

| Scale Dimension | Motivational Governance | Punitive Governance | Cognitive Trust | Affective Trust | HCLEs’ Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| motivational governance | 1.000 | ||||

| punitive governance | 0.453 ** | 1.000 | |||

| cognitive trust | 0.404 ** | 0.212 * | 1.000 | ||

| affective trust | 0.466 ** | 0.154 * | 0.485 ** | 1.000 | |

| HCLEs behavior | 0.402 ** | 0.097 | 0.478 ** | 0.608 ** | 1.000 |

| Scale Dimension | Item | Standardized Factor Loading | AVE | CR | Square Root of AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| motivational governance | motivational governance1 | 0.974 | 0.651 | 0.917 | 0.807 |

| motivational governance2 | 0.766 | ||||

| motivational governance3 | 0.803 | ||||

| motivational governance4 | 0.732 | ||||

| motivational governance5 | 0.746 | ||||

| motivational governance6 | 0.795 | ||||

| punitive governance | punitive governance7 | 0.951 | 0.726 | 0.913 | 0.852 |

| punitive governance8 | 0.836 | ||||

| punitive governance9 | 0.792 | ||||

| punitive governance10 | 0.819 | ||||

| cognitive trust | cognitive trust1 | 0.981 | 0.755 | 0.902 | 0.869 |

| cognitive trust2 | 0.810 | ||||

| cognitive trust3 | 0.804 | ||||

| affective trust | affective trust1 | 1.000 | 0.774 | 0.911 | 0.880 |

| affective trust2 | 0.784 | ||||

| affective trust3 | 0.841 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior | HCLEs’ behavior1 | 0.991 | 0.724 | 0.954 | 0.851 |

| HCLEs’ behavior2 | 0.841 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior3 | 0.818 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior4 | 0.826 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior5 | 0.813 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior6 | 0.833 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior7 | 0.847 | ||||

| HCLEs’ behavior8 | 0.824 |

| Structural Path | B | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affective trust → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.376 | 0.071 | 5.288 | <0.001 |

| Cognitive trust → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.200 | 0.062 | 3.220 | 0.001 |

| Motivational governance → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.198 | 0.075 | 2.644 | 0.008 |

| Punitive governance → HCLEs’ behavior | −0.100 | 0.065 | 1.549 | 0.121 |

| Motivational governance × Affective trust → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.184 | 0.067 | 2.739 | 0.006 |

| Punitive governance × Cognitive trust → HCLEs’ behavior | −0.020 | 0.065 | 0.302 | 0.763 |

| Punitive governance × Affective trust → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.131 | 0.070 | 1.885 | 0.059 |

| Motivational governance × Cognitive trust → HCLEs’ behavior | 0.129 | 0.063 | 2.053 | 0.040 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hou, L.; Yao, B.; Hu, Y.; Yu, K.; Yuan, K. How Trust Affects Hazardous Chemicals Logistics Enterprises’ Sustainable Safety Behavior: The Moderating Role of Government Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083577

Hou L, Yao B, Hu Y, Yu K, Yuan K. How Trust Affects Hazardous Chemicals Logistics Enterprises’ Sustainable Safety Behavior: The Moderating Role of Government Governance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083577

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Li, Bin Yao, Yibo Hu, Keyi Yu, and Kebiao Yuan. 2025. "How Trust Affects Hazardous Chemicals Logistics Enterprises’ Sustainable Safety Behavior: The Moderating Role of Government Governance" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083577

APA StyleHou, L., Yao, B., Hu, Y., Yu, K., & Yuan, K. (2025). How Trust Affects Hazardous Chemicals Logistics Enterprises’ Sustainable Safety Behavior: The Moderating Role of Government Governance. Sustainability, 17(8), 3577. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083577