A Moral Mapping for Corporate Responsibility: Introducing the Local Dimension—Corporate Local Responsibility (COLOR) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Reconstituted Kantian Method for CRPs

2.1. Reconstituted Kantian Method Steps

“As (A),I do the action of (B),in the circumstances of (C),accounting for (D),to bring about (E),unless (F) happens.”

2.2. Reconstituted Kantian Method Application Through Case Studies

“Everyone does the action of (B),in the circumstances of (C),regardless of (D),to bring about (E),unless (F) happens.So do I, as (A).”

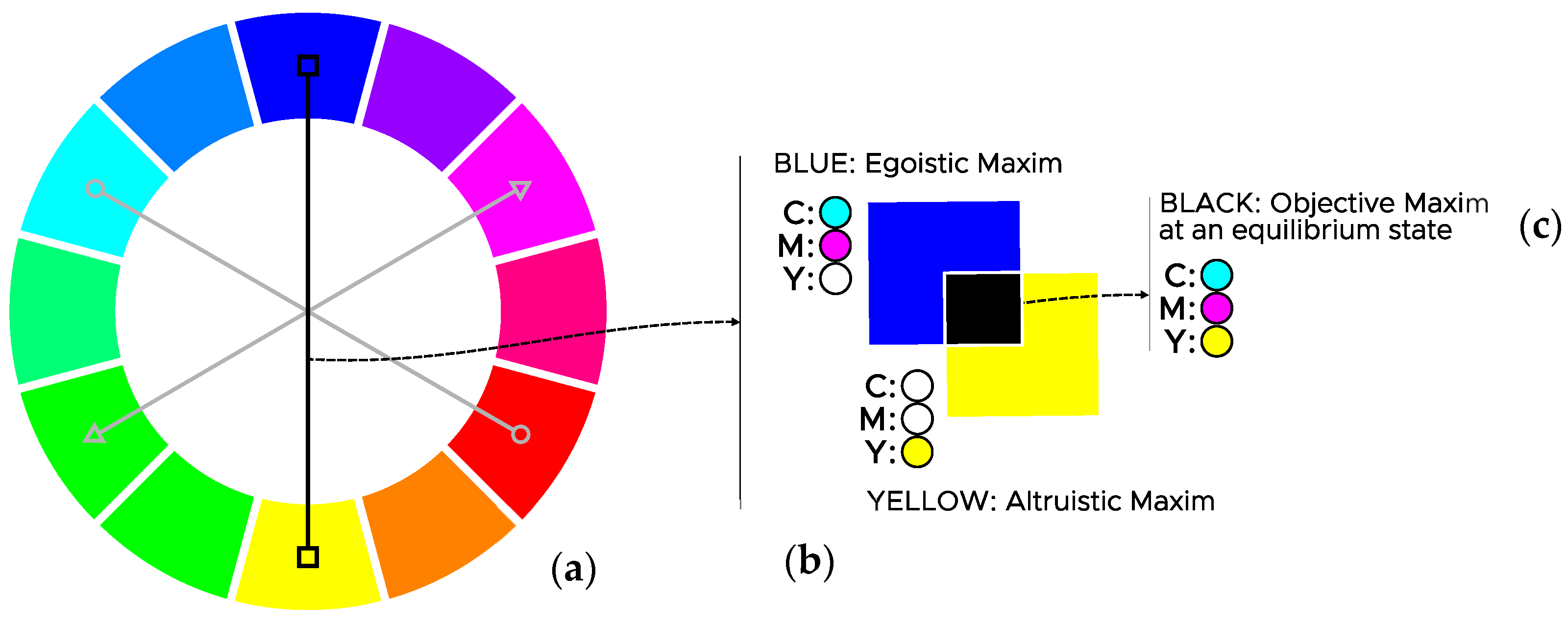

3. Mapping the CRPs

- (a)

- Exclusive policies focus on the welfare of internal sources and philanthropic activities;

- (b)

- The reactive approach prioritizes policies that have serious social demand or changing policies after a strong public reaction;

- (c)

- Integrating audit processes into the corporate structure by following international and national regulatory standards;

- (d)

- Participative policies set up omnichannel communication for all stakeholders and encourage active participation in the feedback mechanism.

- (a)

- Exclusive policies serve the purpose of maximizing shareholder value and generating economic profits;

- (b)

- The main goal of reactive policies is to minimize the loss caused by regulatory costs and public reactions to certain corporate behavior;

- (c)

- Integrative policies prioritize attracting more investment and generating shared value for stakeholders;

- (d)

- The main survival goal for participative policies is to be future-proof, robust, resilient, and strategically sound. This requires incorporating technology into the business model to obtain feedback from stakeholders, identify trends, and build trust.

3.1. Exclusive CRPs

Case Study: Corporate Philanthropy in the Turkish Textile Sector

“As a corporate leader (A),I do the action of initiating a preemptive wage increase for employees (B),in the circumstances of inflationary and competitive pressures (C),accounting for workforce stability and corporate reputation improvement opportunity (D),to bring about reducing employee turnover and increasing productivity (E),unless significant financial constraints or adverse market conditions emerge (F).”

“As a corporate leader (A),I do the action of initiating a preemptive wage increase for employees (B),in the circumstances of inflationary and competitive pressures (C),accounting for my moral imperative to ensure fair compensation (D),to bring about gaining employee loyalty and preserve their dignity (E),unless significant financial constraints or adverse market conditions emerge (F).”

3.2. Reactive CRPs

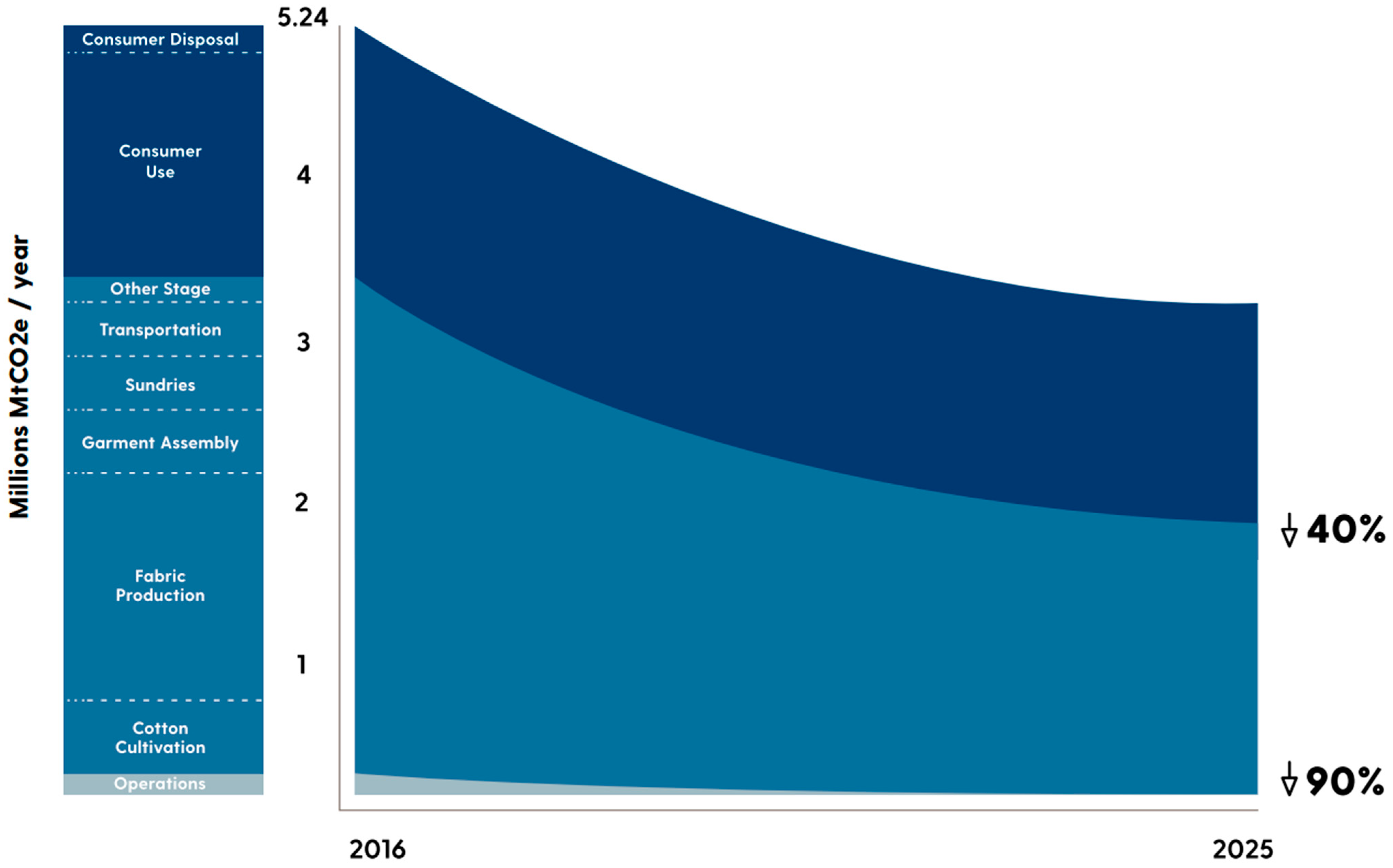

Case Study: Too Dirty to Wear Campaign

“As a corporate executive (A),I do the action of employing a Climate Action Strategy (B),in the circumstances of the pressure from social movements, consumers, and media (C),accounting for protecting corporate reputation and mitigating financial losses (D),to bring about maintaining customer trust and market position (E),unless diminishing public attention makes this strategy redundant (F).”

“As a corporate executive (A),I do the action of employing a Climate Action Strategy (B),in the circumstances of the pressure from social movements, consumers, and media (C),accounting for the long-term impact of the ecological footprint reduction (D),to bring about sustainable operational improvements (E),unless insurmountable financial obstacles prevent effective implementation (F).”

3.3. Integrative CRPs

Case Study: Organic Cotton Fraud in India

“As a supply chain manager (A),I do the action of enhancing due diligence protocols within our supply chain (B),in the circumstances of decreased public trust due to the certification scandals (C),accounting for the ineffectiveness of these new protocols (D),to bring about attracting more responsible investment (E),unless another systemic regulatory scandal arises (F).”

“As a supply chain manager (A),I do the action of enhancing due diligence protocols within our supply chain (B),in the circumstances of the decreasing public trust due to the certification scandals (C),accounting for our obligation to spot inefficiencies and uphold industry benchmarks (D),to bring about improving stakeholder trust and setting higher industry standards (E),unless a more effective and comprehensive regulatory framework is established (F).”

3.4. Participative CRPs

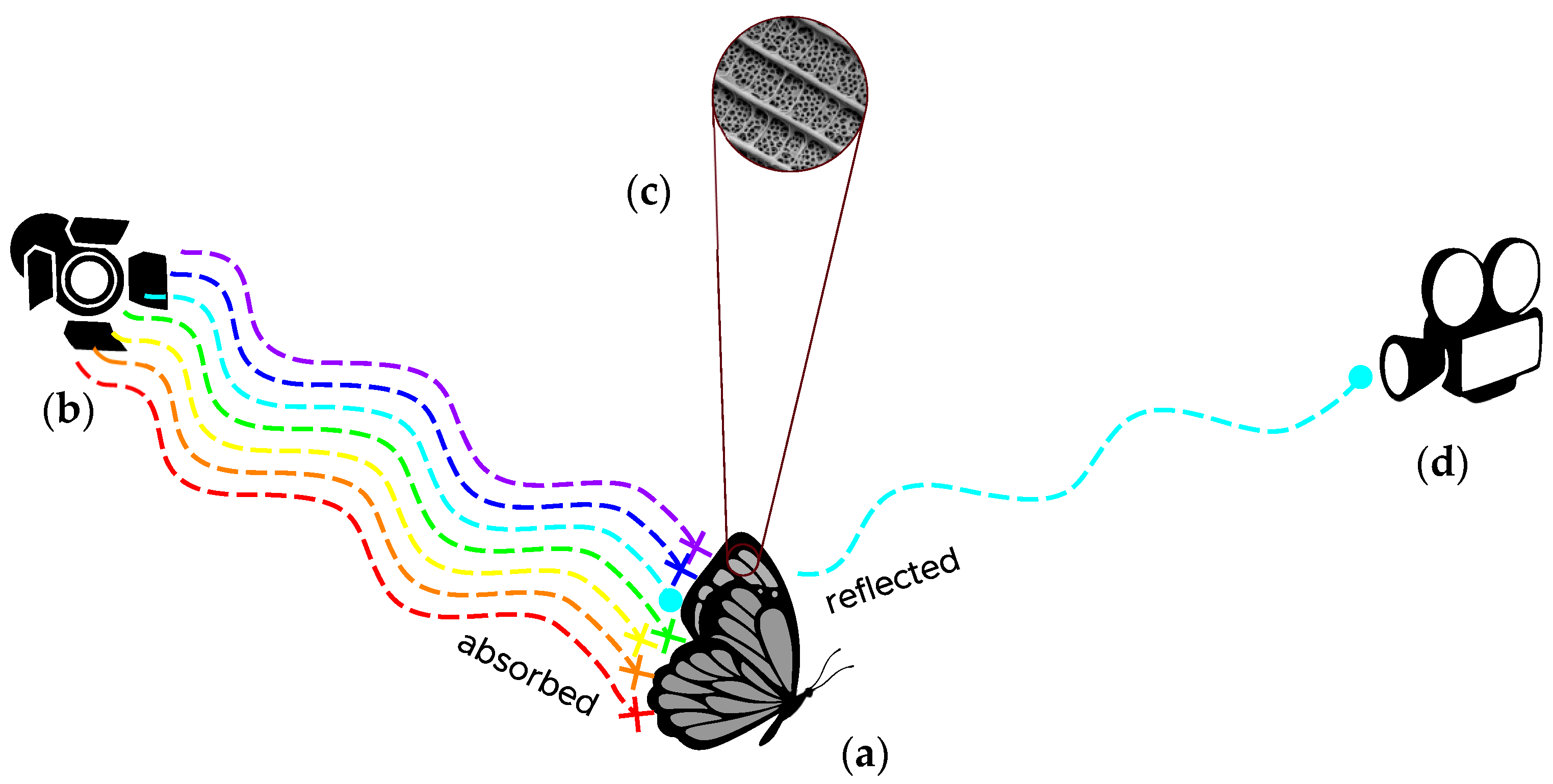

A New Model: COLOR

- Operational Element: As we would like to observe the immediate surroundings of the business, this element refers to the object. Enabling companies to incorporate diverse perspectives at all levels, the operational element ensures that local stakeholders and workers actively shape decision-making. It encourages corporate leaders to nurture a culture of collective accountability, structural innovation, and participatory decision-making. Rewarding favored ideas while discouraging harmful initiatives helps all immediate stakeholders work toward common goals.

- Movement Element: Since it represents the outside influence and sheds light on the real shades of corporate actions, movement element represents the light source. CRPs have to respond to evolving public expectations; therefore, it stresses trust-building, public scrutiny, and grassroots activities to guarantee that business strategies are consistent with community values. An effective change management mechanism is, therefore, a necessity to drive robust change.

- Regulation Element: Corresponding to the standardized procedures as the scales attached to the object, resonates with the texture. It promotes transparency through the availability of high-quality data collection and knowledge-sharing platforms, inviting stakeholders to examine corporate claims and contribute to responsible policymaking. The high-quality data enable experts to simulate the needs and expectations of stakeholders to make CRPs more resilient to the changing conjuncture.

- Collaboration Element: This is the eyes of the local communities that scrutinize and look into a different perspective to improve processes, which are the receptors. Establishing localized decision-making structures that allow affected communities to shape business policies. It offers a modular approach based on the idea that decisions should be made closer to the effects of an action. Thus, responsibility is distributed across all levels of business operations.

4. Discussion

“Everyone does the action of initiating a preemptive wage increase for employees (B),in the circumstances of inflationary and competitive pressures (C),regardless of my moral imperative or the reputation improvement opportunity (D),to bring about fulfilling our obligation to the local stakeholders (E),unless significant financial constraints or adverse market conditions emerge (F).So do I, as a corporate leader (A).”

“Everyone does the action of employing a Climate Action Strategy (B),in the circumstances of high ecological impact in our supply chain (C),regardless of the pressure from social movements, consumers, and media (D),to bring about maintaining customer and stakeholder trust (E),unless insurmountable financial obstacles prevent effective implementation (F).So do I, as a corporate executive (A).”

“Everyone does the action of enhancing due diligence protocols within supply chains (B),in the circumstances of noticing shortcomings of standardization processes (C),regardless of decreased public trust due to the certification scandals (D),to bring about setting higher industry standards (E),unless a more effective and comprehensive regulatory framework is established (F).So do I, as a supply chain manager (A).”

5. Cross-Sectoral Applications, Limitations, and Future Implications

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The virtue ethics versus ethical egoism debate took us to the “enlightened industrialists,” the businesspeople (1) of early industrial capitalism, who were concerned about the living conditions of (2) employees and took initiative for (3) coercive bodies to change the law.

- (2)

- The consequentialism versus ethical egoism debate led us to (4) social movements, which formed (5) labor associations and (6) civil society organizations, and altogether they demanded specific actions from other stakeholders.

- (3)

- The deontological ethics versus ethical egoism debate introduced us (7) professional associations, (8) independent researchers, and (9) standard-setting bodies, which are working on rules and regulations to check and balance corporate impact.

- (4)

- The social contract versus ethical egoism debate showed the rise in (10) customers and (11) media figures after the developments in information technologies. They started forming social contracts with business stakeholders, independent stakeholders, and non-business stakeholders and (12) broader stakeholders, like local communities, minorities, and other discriminated groups.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CMYK | Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, and Black (or Key) |

| COLOR | Corporate Local Responsibility |

| CR | Corporate Responsibility |

| CRPs | Corporate Responsibility Policies |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CT | Color Theory |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| GOTS | Global Organic Textile Standard |

| GRS | Global Recycling Standard |

| ILO | International Labor Organization |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| MNCs | Multinational Corporations |

| NGO | Non-governmental Organization |

| PR | Public Relations |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| USA | United States of America |

References

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: Evolution of a Definitional Construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Hatch, N.W. Researching Corporate Social Responsibility: An Agenda for the 21st Century. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awa, H.O.; Etim, W.; Ogbonda, E. Stakeholders, Stakeholder Theory and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Moon, J. “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A Conceptual Framework for a Comparative Understanding of Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 404–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, O.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Structural Change in Financial Services. Manag. Audit. J. 2004, 19, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankental, P. Corporate Social Responsibility—A PR Invention? Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Liedtka, J. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Critical Approach. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, R. Defining Sustainability. In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Sustainability; Brinkmann, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-3-031-01948-7. [Google Scholar]

- Klarin, T. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From Its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad Strokes towards a Grand Theory in the Analysis of Sustainable Development: A Return to the Classical Political Economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. Tracing the Journey of Sustainability Practices, the Historical Evolution Through the Industrial Revolutions. In Sustainable Finance and Business in Sub-Saharan Africa; Mhlanga, D., Dzingirai, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 15–29. ISBN 978-3-031-74050-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bakardjieva, R. Sustainable Development and Corporate Social Responsibility: Linking Goals to Standards. J. Innov. Sustain. 2016, 2, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostepaniuk, A.; Nasr, E.; Awwad, R.I.; Hamdan, S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. Managing a Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayman-Bacchus, L.; Walsh, P.R. Theorising Corporate Responsibility and Sustainable Development. In Corporate Responsibility and Sustainable Development; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-315-14252-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, T.; Elbanna, S. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Implementation: A Review and a Research Agenda Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 183, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Jain, T. Unpacking Micro-CSR through a Computational Literature Review: An Identity Heterogeneity View of Internal Stakeholders. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Sánchez, F.J.; Molina-Prados, A.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Moral-Cuadra, S. Exploring the Three-Dimensional Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Equity, Corporate Reputation, and Willingness to Pay. A Study of the Fashion Industry. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP Threads of Change: Perspectives on a Systemic Transformation in the Textile Sector. Available online: https://www.unep.org/technical-highlight/threads-change-perspectives-systemic-transformation-textile-sector (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Frederick, W.C. From CSR1 to CSR2: The Maturing of Business-and-Society Thought. Bus. Soc. 1994, 33, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-674-25578-4. [Google Scholar]

- Scharding, T. Individual Actions and Corporate Moral Responsibility: A (Reconstituted) Kantian Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulia, P.; Behura, A.K.; Sarita, S. The Moral Imperatives of Sustainable Development: A Kantian Overview. Probl. Ekorozwoju 2018, 13, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.; Dubbink, W. Understanding the Role of Moral Principles in Business Ethics: A Kantian Perspective. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 205–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, T.M. A Kantian Justification of Fair Shares: Climate Ethics and Imperfect Duties. Ethics Policy Environ. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K. A Kantian Perspective on Individual Responsibility for Sustainability. Ethics Policy Environ. 2021, 24, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, B. The Practice of Moral Judgment; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-674-69717-1. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, M.C. The Decomposition of the Corporate Body: What Kant Cannot Contribute to Business Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M.C. Kant and Applied Ethics: The Uses and Limits of Kant’s Practical Philosophy, 1st ed.; Wiley: West Sussex, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-470-65766-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E.J. The Age of Revolution: 1789–1848; First Vintage Books edition; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-679-77253-8. [Google Scholar]

- EuroCommerce. European Textiles Global Value Chain Report; Reports and Studies—Environment, Sustainability & Energy; EuroCommerce: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe, S.; Dominish, E.; Martinez-Fernandez, C.; International Labour Organization; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Taking Climate Action: Measuring Carbon Emissions in the Garment Sector in Asia; ILO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022; ISBN 978-92-2-035325-7. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.K.; Hossain, F.; Khan, B.U.; Rahman, M.; Asad, M.A.Z.; Akter, M. Circular Economy: A Sustainable Model for Waste Reduction and Wealth Creation in the Textile Supply Chain. SPE Polym. 2025, 6, e10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Azmat, F.; Fujimoto, Y.; Hossain, F. Exploitation in Bangladeshi Ready-Made Garments Supply Chain: A Case of Irresponsible Capitalism? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2023, 34, 164–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future; Conker House: Stroud, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Audit Committee. Fixing Fashion: Clothing Consumption and Sustainability; Authority of the House of Commons: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, K.; Mason, M.; Williams, C.; Davidson, M.; O’Callaghan, B.; Hepburn, C. Industrial Need for Carbon in Products; Final 25% Series Paper; Oxford Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Global Plastics Outlook: Economic Drivers, Environmental Impacts and Policy Options; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 978-92-64-65494-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vennesson, P. Case Studies and Process Tracing: Theories and Practices. In Approaches and Methodologies in the Social Sciences; Della Porta, D., Keating, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 223–239. ISBN 978-0-521-88322-1. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffee, E.C. The Origins of Corporate Social Responsibility. Univ. Cin. Law Rev. 2017, 85. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2957820 (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- Agudelo, M.A.L.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A Literature Review of the History and Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A History of Corporate Social Responsibility: Concepts and Practices. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., Matten, D., McWilliams, A., Moon, J., Siegel, D.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 19–46. ISBN 978-0-19-921159-3. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.E. Corporate Social Responsiveness: An Evolution. Univ. Mich. Bus. Rev. 1978, 30, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the s Back in Corporate Social Responsibility: A Multilevel Theory of Social Change in Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26000:2010; Guidance on Social Responsibility. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Friedman, M. The Social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Time Magazine, 13 September 1970; pp. 32–33, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Arjoon, S. Virtue Theory as a Dynamic Theory of Business. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 28, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, R.C. Corporate Roles, Personal Virtues: An Aristotelean Approach to Business Ethics. Bus. Ethics Q. 1992, 2, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, R. Egoism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Engels, F. The Condition of the Working Class in England; McLellan, D., Ed.; The world’s classics; 1. publ.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993; ISBN 978-0-19-282955-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, 1953rd ed.; Univ. of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-60938-196-7. [Google Scholar]

- Morais, H.M. Marx and Engels on America. Sci. Soc. 1948, 12, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, G. The Truly Responsible Enterprise: About Unsustainable Development, the Tools of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Deeper, Strategic Approach; KÖVET-Hungarian Association for Sustainable Economies: Budapest, Hungary, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers: A Holistic Perspective on Corporate Sustainability Drivers. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melé, D. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., Matten, D., McWilliams, A., Moon, J., Siegel, D.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 47–82. ISBN 978-0-19-921159-3. [Google Scholar]

- Osho, G.; Ashe, C.; Wickramatunge, J. Correlation of Morale, Productivity and Profit in Organizations. Natl. Social. Sci. J. 2006, 26, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ergül, B.; Davud, D. Asgari Ücreti Beklemeyen Firmalar, Zammı Erkene Çekti! Maaşlara Yüzde 15 Iyileştirme. Available online: https://www.haberler.com/ (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Göçer Akder, D.; Bahçecik, Ş.O. The Impact of Brand-Supplier Relations on Producers in the Earthquake Zone, Turkey 2023; Middle East Technical University: Ankara, Turkey, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and Society: The Link between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott-Armstrong, W. Consequentialism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Nodelman, U., Eds.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zadek, S. Doing Good and Doing Well: Making the Business Case for Corporate Citizenship; Research Report; Conference Board: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8237-0731-7. [Google Scholar]

- Crossley, N. Making Sense of Social Movements; Open University Press: Buckingham, PA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-335-20603-2. [Google Scholar]

- Touraine, A. The Voice and the Eye: An Analysis of Social Movements; Cambridge University Press, Maison des sciences de l’homme: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1981; ISBN 978-0-521-23874-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrow, S. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-521-62072-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, D. Sustainable Development. In Dictionary of Corporate Social Responsibility: CSR, Sustainability, Ethics and Governance; Idowu, S.O., Capaldi, N., Fifka, M.S., Zu, L., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-10535-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stand.earth Climate Pollution Protests with “Too Dirty to Wear” Campaign Begin at Levi’s Flagship San Francisco Store. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20171215062406/https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/climate-pollution-protests-with-too-dirty-to-wear-campaign-begin-at-levis-flagship-san-francisco-store-300571821.html (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Levi Strauss & Co. Climate Action. Strategy 2025; Levi Strauss & Co: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levi Strauss & Co. Climate Transition Plan: As of October 2024; Levi Strauss & Co: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B. Some Problems in the Sociology of the Professions. Daedalus 1963, 92, 669–688. [Google Scholar]

- Wilensky, H.L. The Professionalization of Everyone? Am. J. Sociol. 1964, 70, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.T.; Kim, S. Specialization and Regulation: The Rise of Professionals and the Emergence of Occupational Licensing Regulation. J. Econ. Hist. 2005, 65, 723–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Epstein, S. A World of Standards but Not a Standard World: Toward a Sociology of Standards and Standardization. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2010, 36, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herciu, M. ISO 26000—An Integrative Approach of Corporate Social Responsibility. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2016, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B.; Primiana, I.; Sarasi, V.; Satyakti, Y. Sustainability Innovation in the Textile Industry: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Textile Exchange. Organic Cotton Market Report; Textile Exchange: Lamesa, TX, USA, 2022; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- GOTS GOTS Detects Evidence of Organic Cotton Fraud in India—GOTS—Global Organic Textile Standard. Available online: https://global-standard.org/news/gots-press-release-gots-detects-evidence-of-organic-cotton-fraud-in-india (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- TextileToday GOTS Finds ‘Gigantic Scale’ Fraud in India Organic Cotton. Available online: https://www.textiletoday.com.bd/gots-finds-gigantic-scale-fraud-india-organic-cotton/ (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Ghosh, S. Global Confidence in Organic Cotton Dips. Reason: The Great Indian Organic Cotton Scam. Available online: https://texfash.com/special/global-confidence-in-organic-cotton-dips-reason-the-great-indian-organic-cotton-scam (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- GOTS GOTS Version 7.0 Released: Major Leap Forward for the Sustainable All-Inclusive Solution for Organic Fibre Processing —GOTS—Global Organic Textile Standard. Available online: https://global-standard.org/news/gots-annual-pr-2023 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- GOTS Certification Bans—GOTS—Global Organic Textile Standard. Available online: https://global-standard.org/the-standard/protection/certification-bans (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Hobbes, T. Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclasiasticall and Civil; Andrew Crooke, at the Green Dragon in St. Paul’s Church-yard: London, UK, 1651; ISBN 978-1-4392-9725-4. [Google Scholar]

- Svanberg, M.K.; Svanberg, C.F.C. The Anti-Egoist Perspective in Business Ethics and Its Anti-Business Manifestations. Philos. Manag. 2022, 21, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does Doing Good Always Lead to Doing Better? Consumer Reactions to Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.; Chipriyanova, G.; Krasteva-Hristova, R. Integration of Digital Technologies in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Activities: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.J.; Vu, M.C.; Williams, C. Building Skillful Resilience Amid Uncertainty. In The Palgrave Handbook of Corporate Sustainability in the Digital Era; Park, S.H., Gonzalez-Perez, M.A., Floriani, D.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 379–395. ISBN 978-3-030-42411-4. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A.E. Artists’ Colors and Newton’s Colors. Isis 1994, 85, 600–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Vinci, L.; Rigaud, J.F.; John, F.; Brown, J.W. A Treatise on Painting; J.B. Nichols and Son: London, UK, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G. International Trade and Industrial Upgrading in the Apparel Commodity Chain. J. Int. Econ. 1999, 48, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçer, D. The Impact of the Earthquake on Textile and Garment Workers; Clean Clothes Campaign Turkey: Istanbul, Turkey, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hisarlı, D.; Demir, B. Turkey’s Garment Industry Profile and the Living Wage; Clean Clothes Campaign Turkey: Istanbul, Turkey, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Çetin, M.B.; Gündüz, S. From Boom to Bust: Unravelling the Global Tech Layoffs Phenomenon. In Economic Uncertainty in the Post-Pandemic Era; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-1-00-346107-4. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Industrial Sector | Mean Product Lifetime (Years) [37] | Mechanically Recyclable Polymer (%) [38] | Plastic Waste Generation, 2019 (%) [39] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Packaging | 0.5 | 91 | 40 |

| Consumer and Institutional Products | 3 | 72 | 12 |

| Textiles | 5 | 100 | 11 |

| Electrical/Electronic | 8 | 36 | 4 |

| Transportation | 13 | 61 | 10 |

| Industrial Machinery | 20 | 86 | 0.4 |

| Building and Construction | 35 | 39 | 5 |

| Case Study | Corporate Philanthropy in the Turkish Textile Sector | Too Dirty to Wear Campaign | Organic Cotton Fraud in India |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral agent within the company | The business owner | Chief executives | Specialized departments |

| Source of data | Local news, research reports, in-sector interviews | Company communications and protesting social movement reports | Lab result reports, news, and the certification provider’s communications |

| Action trigger | Currency crisis causing high inflation | Protests and boycotts organized by a social movement | Lab test results and certification criteria mismatch |

| Function in the textile value chain | Supplier | Retailer | Certification/Audit |

| Action | Raising worker salaries before the salary renewal period | Implementing a climate action strategy for 2025 | Removing fraudulent companies from the system |

| Consequence | Remained ad hoc | Complied with the 2025 agenda and issued its own audit system for its supply chain | Learning from the inefficiencies, taking measures to improve audit processes |

| CRP Groups | (a) Exclusive CRPs | (b) Reactive CRPs | (c) Integrative CRPs | (d) Participative CRPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who is responsible? (Moral Agent) | The business owner, Leaders | Business owners, Chief Executives, Leaders | Chief Executives, Specialized departments, and their managers | Individuals who make a decision suggest opinions for the decision or supervise at any level of corporate policymaking |

| Public access to crucial knowledge (Transparency) | Prohibited | Restricted | Partially allowed | Encouraged |

| Responsible for doing/complying with (Key terms) | Charity, philanthropy, and civic activities that are mostly related to the welfare of its internal stakeholders | Preserving corporate image, obtaining certificates and memberships that contribute to public trust | Complying with Legal Acts, National Regulations, and International Standards, like ISO26000 [47], scientific principles | Full transparency and scrutiny over the product, stakeholder involvement in decision-making, consumer education |

| Source of altruistic ethics | Actor-based (Virtue Theory) | Results-based (Consequentialism) | Actions-based (Deontology) | Contract-based (Social Contract) |

| Guided by | The arbitrary moral vision of the Leader | Public reactions and scandals, PR or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)communication experts, media, consumers, stockholders, opinion leaders | Independent auditors, outsourced specialists, international organizations, the international community | Public scrutiny |

| CR perception | Personal decisions of businesspeople | Decision-making process responsive to societal demand | Strategic necessity | A business model that integrates all parties affected by the business activity into the decision-making process |

| Corporate business goal | Generating economic profits | Evading regulatory costs | Attracting responsible investment | Gaining stakeholder trust to achieve a robust business model |

| Maximizing share-holder value | Generating shared value | Securing competitive-ness with sector-wide accepted principles | Creating a company culture of transparency and shared responsibility | |

| Motivation of the decision-maker (egoist) | Profit, wealth, and/or reputation maximization | Minimizing the loss by overseeing unexpected incidents | Keeping business as usual by standardized safer policies | Pursuing individual self-interest to be heard in the wider community |

| (altruist) | Well-being of closer stakeholders, i.e., workers and their families | Utilizing maximum benefits for society | Sustainable growth based on corporate strategy and rules | Building resilient relationships with all stakeholders |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çetin, M.B.; Gündüz, S. A Moral Mapping for Corporate Responsibility: Introducing the Local Dimension—Corporate Local Responsibility (COLOR). Sustainability 2025, 17, 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083495

Çetin MB, Gündüz S. A Moral Mapping for Corporate Responsibility: Introducing the Local Dimension—Corporate Local Responsibility (COLOR). Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083495

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇetin, Mahmut Berkan, and Selim Gündüz. 2025. "A Moral Mapping for Corporate Responsibility: Introducing the Local Dimension—Corporate Local Responsibility (COLOR)" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083495

APA StyleÇetin, M. B., & Gündüz, S. (2025). A Moral Mapping for Corporate Responsibility: Introducing the Local Dimension—Corporate Local Responsibility (COLOR). Sustainability, 17(8), 3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083495