Integrating the Cross-Border Industrial Chain: An Exploring of Key Configuration of Agricultural Investment in Lancang-Mekong River Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Value Chain and International Division of Labor Theoretical Support

2.2. Expanding the International Market for Agricultural Products Requires Agricultural Enterprises to Improve Their Industrial Links

2.3. The Development of Cross-Border Agricultural Industry Chains Requires Innovation Management Mechanisms

2.4. The Development and Integration of Agricultural Industry Chains and Innovation Chains Require Technological Support

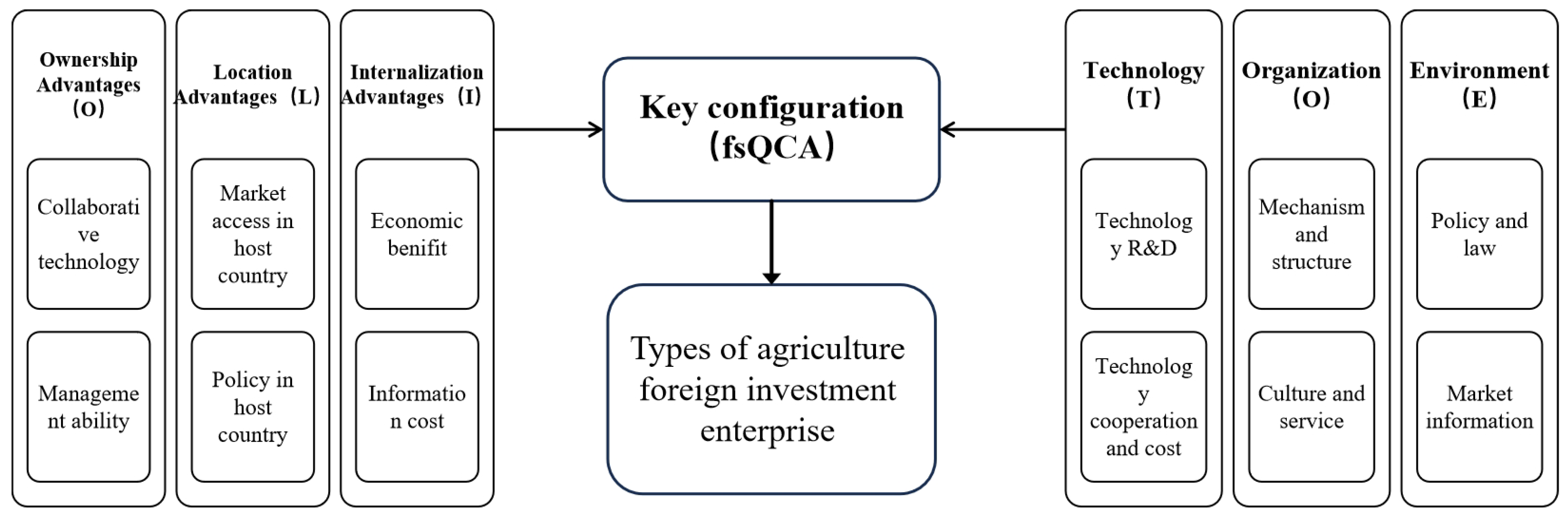

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Empirical Analysis Strategies

3.2. Survey Context

3.3. Survey Design

3.4. Data and Variables

4. Results

4.1. Data Calibration and Necessary Conditions

4.2. Conditional Configuration Analysis

| Configurations | ATC Strength-Oriented | ATC Potential-Oriented | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | C6 | |

| FDI |  |  | ● |  | ||

| EB | ● | ● | ● |  |  | |

| IS |  | ● | ● |  |  | |

| LCM | ● |  | ● | ● | ● | |

| CPS |  | ● | ● | ● | ||

| FPS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| raw coverage | 0.1430 | 0.1318 | 0.0875 | 0.2692 | 0.1547 | 0.2996 |

| unique coverage | 0.0157 | 0.0633 | 0.0340 | 0.0837 | 0.0459 | 0.0668 |

| consistency | 0.9985 | 0.9984 | 0.9952 | 0.9855 | 0.9750 | 0.9522 |

| solution coverage | 0.5582 | |||||

| solution consistency | 0.9716 | |||||

represents core existence or non-existence condition, while a small-size ● or

represents core existence or non-existence condition, while a small-size ● or  indicates marginal existence or non-existence condition. However, the current configuration results reveal that only marginal existence conditions are present (small size ●). Meanwhile, a marginal non-existence condition (small size

indicates marginal existence or non-existence condition. However, the current configuration results reveal that only marginal existence conditions are present (small size ●). Meanwhile, a marginal non-existence condition (small size  ) is only observed in the LCM component of Configuration C2, the blank means the condition existed or not.

) is only observed in the LCM component of Configuration C2, the blank means the condition existed or not.4.3. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Main Conclusions

5.2. Highlights and Contributions

5.3. Discussion and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WB (World Bank). Agriculture Finance & Agriculture Insurance, 2022-08-31. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/brief/agriculture-finance (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Sun, Y.Q. Review and Reflection on China’s Agricultural Overseas Investment and Cooperation Journey. J. Int. Econ. Coop. 2014, 10, 42–45. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, P. Does the Belt and Road Initiative increase the green technology spillover of China’s OFDI? An empirical analysis based on the DID method. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 1043003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liu, Y. A study on agricultural investment along the Belt and Road. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 1036958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Z.; He, Q. Time lag analysis of FDI spillover effect: Evidence from the Belt and Road developing countries introducing China’s direct investment. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2020, 15, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Z. China’s Agricultural Diplomacy Under the “Going Global” Strategy. China Q. Int. Strateg. Stud. 2019, 5, 557–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, P.F.; Zhang, L.B. Report of China’s Agricultural Foreign Investment Cooperation (2021); China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.Y.; Hu, Z.Q. Study on Foreign Agricultural Investments of China’s Agricultural Enterprises under the Belt and Road. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 3, 93–101. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.S.; Kang, W.W.; Jing, R.Q. Analysis on New Mode of “Going Out” of Chinese Private Agricultural Enterprises—Based on Perspective of Whole Industry Chain. Agric. Econ. Manag. 2021, 1, 58–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Song, J. Analysis of the threshold effect of agricultural industrial agglomeration and industrial structure upgrading on sustainable agricultural development in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 341, 130818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCC (Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China), 2021 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment, 2022-11-07. Available online: http://file.mofcom.gov.cn/article/xwfb/xwrcxw/202211/20221103365310.shtml (accessed on 7 November 2022). (In Chinese)

- Doss, C.R. Analyzing technology adoption using micro-studies: Limitations, challenges, and opportunities for improvement. Agric. Econ. 2006, 34, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Y.; Pandey, S.; Hu, F.Y.; Xu, P.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Deng, X.; Feng, L.; Wen, L.; Li, J.; et al. Farmers’ adoption of improved upland rice technology for sustainable mountain development in southern Yunnan. Mt. Res. Dev. 2010, 30, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Meriluoto, L.; Reed, W.R.; Tao, D.; Wu, H. The impact of agricultural technology adoption on income inequality in rural China: Evidence from southern Yunnan province. China Econ. Rev. 2011, 22, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, Y.; Godo, Y. Development economics: From the poverty to the wealth of nations. Oup Cat. 2011, 36, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X.X.; Lu, L.; Reardon, T.; Zilberman, D. Economics of agricultural supply chain design: A portfolio selection approach. In Proceedings of the Allied Social Sciences Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–5 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Jia, F.; Brown, S.; Koh, L. Supply chain learning of sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: A resource orchestration perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1061–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, V.L.; Kovaleski, J.L.; Pagani, R.N. Technology transfer in the supply chain oriented to industry 4.0: A literature review. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 546–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, P.K. One size fits all? Heckscher-Ohlin specialization in global production. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 686–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Rossi-Hansberg, E. Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. Am. Econ. Rev. 2008, 98, 1978–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Li, Q.; Xie, J. Based on data envelopment analysis to evaluate agricultural product supply chain performance of agricultural science and technology parks in China. Custo. AgronegÓCio Online 2019, 15, 314–327. [Google Scholar]

- Borgers, A.; Derwall, J.; Koedijk, K.; Ter Horst, J. Do social factors influence investment behavior and performance? Evidence from mutual fund holdings. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 60, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, P. Factors Influencing the Investment Behavior of Women Investors: An Empirical Investigation. IUP J. Financ. Risk Manag. 2019, 16, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lan, H.L.; Chen, W.H.; Zeng, P. Research on the antecedent configuration and performance of strategic change. J. Manag. World 2020, 9, 168–185. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.T.; Xia, Y. The analysis of the key influencing factors of the effective development of rural collective economy: Based on qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) method. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2020, 41, 138–145. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NJ, USA, 1985; Volume 43, p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- Gereffi, G.; Humphrey, J.; Sturgeon, T. The governance of global value chains. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2005, 12, 78–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott, P.K. Across-product versus within-product specialization in international trade. Q. J. Econ. 2004, 119, 647–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.P. Research on vertical coordination mode of agricultural industry chain-characteristics, choice and governance. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2019, 47, 305–310. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Muflikh, Y.N.; Smith, C.; Aziz, A.A. A systematic review of the contribution of system dynamics to value chain analysis in agricultural development. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Wang, J.M.; Zhong SRWu, B.; Feng, L.; Si, Z.Z. Land-based cooperation for alternative livelihoods in Laos: Case studies of Chinese agricultural companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, B.; Yeung, M.; Laforet, S. China’s outward foreign direct investment: Location choice and firm ownership. J. World Bus. 2012, 47, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Xu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, L. Chinese industrial outward FDI location choice in ASEAN countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, P.; Nenci, S. Does global value chain participation and positioning in the agriculture and food sectors affect economic performance? A global assessment. Food Policy 2022, 108, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Zhong, M.; Liu, W.; Chen, B. Belt and Road Initiative and OFDI from China: The paradox of home country institutional environment between state and local governments. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2023, 17, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.D. Understanding China’s growth: Past present and future. J. Econ. Perspect. 2012, 26, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.K.; Ding, J. Forty years of China’s agricultural development and reform and the way forward in the future. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2018, 3, 4–15. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Anandajayasekeram, P.; Gebremedhin, B. Integrating Innovation Systems Perspective and Value Chain Analysis in Agricultural Research for Development: Implications and Challenges; ILRI (aka ILCA and ILRAD): Nairobi, Kenya, 2009; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Touzard, J.-M.; Temple, L.; Faure, G.; Triomphe, B. Innovation Systems and Knowledge Communities in the Agriculture and Agrifood Sector: A Literature Review. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2015, 2, 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, G.; Knierim, A.; Koutsouris, A.; Ndah, H.T.; Audouin, S.; Zarokosta, E.; Wielinga, E.; Triomphe, B.; Mathé, S.; Temple, L.; et al. How to strengthen innovation support services in agriculture with regard to multi-stakeholder approaches. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2019, 28, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. The Eclectic Paradigm of International Production: A Restatement and Some Possible Extensions. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1988, 19, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Greckhamer, T.; Mossholder, K.W. Qualitative comparative analysis and strategic management research: Current state and future prospects. In Building Methodological Bridges (Research Methodology in Strategy and Management, Vol. 6); Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; pp. 259–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, X.J.; Wang, F.B. The application of qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in Configuration research in business administration field: Commentary and future directions. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2017, 39, 68–83. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Welles, J.S.; Soriano, N.; Dorbu, F.E.; Pereira, G.M.; Rubeck, L.M.; Timmermans, E.L.; Ndayambaje, B.; Deviney, A.V.; Classen, J.J.; Koziel, J.A.; et al. Socio-economic and governance conditions corresponding to change in animal agriculture: South Dakota case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, R.; Zhan, M.; Wang, F. What determines the development of a rural collective economy? A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) approach. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 506–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.; Wulf, J. Innovation and Incentives: Evidence from Corporate R&D. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 634–644. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, Z.; Sun, Y. System identification of enterprise innovation factor combinations—A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis method. Systems 2024, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Tao, D. Construction of Cross-border Agricultural Cooperation Mechanism from the Perspective of Science and Technology Diplomacy: Rethinking Management and Development of the “South and Southeast Asia Agricultural Science and Technology Radiation Center”. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2022, 3, 53–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- YASS (Yunnan Academy of Social Sciences), China. 2019-07-23. Available online: http://www.ynssky.cn/xsyj/zgsd/8168538898571437457 (accessed on 23 July 2019). (In Chinese).

- NDRC (National Development and Reform Commission), China. 2020-10-21. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/jianyitianfuwen/qgzxwytafwgk/202107/t20210708_1289727.html (accessed on 21 October 2020). (In Chinese)

- YPSTD (Yunnan Province Science and Technology Department), China. 2021-11-22. Available online: http://kjt.yn.gov.cn/html/2021/zhongdianlingyuzhengfuxinxigongkai_1122/5091.html (accessed on 22 November 2021)In Chinese.

- Lu, J.; Dev, L.; Petersen-Rockney, M. Criminalized crops: Environmentally-justified illicit crop interventions and the cyclical marginalization of smallholders. Political Geogr. 2022, 99, 102781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Feng, L. Success Factors of Cross-Border Agricultural Investments for Opium Poppy Alternative Project under China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Development intervention and transnational narcotics control in northern Myanmar. Geoforum 2016, 68, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Fuzzy-Set Social Science; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Fan, G.; Hu, L.P. Marketization Index of China’s Province NERI Report 2018; Social Sciences Academic Press (China): Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L. Can China’s agricultural FDI in developing countries achieve a win-win goal?—Enlightenment from the literature. Sustainability 2018, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better casual theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organizational research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.C. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2008; pp. 193–214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y.Z. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in management and organization research: Position, tactics, and directions. Chin. J. Manag. 2019, 16, 1312–1323. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jacqueminet, A.; Durand, R. Ups and downs: The role of legitimacy judgment cues in practice implementation. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 1485–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misangyi, V.F.; Acharya, A.G. Substitutes or complements? A configurational examination of corporate governance mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1681–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, J. Revisiting international business theory: A capabilities-based theory of the MNE. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Swinnen, J.; Kuijpers, R. Value chain innovations for technology transfer in developing and emerging economies: Conceptual issues, typology, and policy implications. Food Policy 2019, 83, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, K.; Estrin, S.; Bhaumik, S.K.; Peng, M.W. Institutions, resources and entry strategies in emerging economies. LSE Res. Online Doc. Econ. 2009, 30, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measure Descriptives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Type ** | Mean | SD | Max | Min | |

| ATC * (Agro-enterprise Technical Collaboration) | No = 0; Yes = 1 | A | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.00 |

| FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) | Proportion of investment flows to total assets % | C | 0.80 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.55 |

| EB (Economic Benefits) | Annual income to total assets % | C | 0.99 | 1.07 | 1.79 | 0.28 |

| IS (Information Source) | Options percentage of government information source % | B | 0.36 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 0.33 |

| LCM (Language Context Management) | Option percentage of management in local language % | B | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| CPS (Chinese Policy Support) | Option percentage of tax reduction policy by China % | B | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 0.25 |

| FPS (Foreign Policy Support) | Option percentage of tax reduction policy by host country % | B | 0.34 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| Variables | Calibration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Affiliated | Intersection | Not Affiliated | ||

| outcome variable | ATC | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| conditional variables | FDI | 1 | 0.84 | 0.39 |

| EB | 1.26 | 0.56 | 0.23 | |

| IS | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.14 | |

| LCM | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.25 | |

| CPS | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0 | |

| FPS | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Conditions Tested | ATC | ~atc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| FDI | 0.6354 | 0.7570 | 0.8023 | 0.3614 |

| ~fdi | 0.4640 | 0.8612 | 0.4605 | 0.3233 |

| EB | 0.5888 | 0.7516 | 0.7675 | 0.3705 |

| ~eb | 0.5068 | 0.8522 | 0.4854 | 0.3086 |

| IS | 0.5665 | 0.8196 | 0.7974 | 0.4363 |

| ~is | 0.6104 | 0.8885 | 0.6703 | 0.3690 |

| LCM | 0.6060 | 0.7957 | 0.8277 | 0.4110 |

| ~lcm | 0.5515 | 0.8943 | 0.5886 | 0.3610 |

| CPS | 0.6960 | 0.7817 | 0.8426 | 0.3579 |

| ~cps | 0.4283 | 0.8780 | 0.4859 | 0.3767 |

| FPS | 0.8609 | 0.8131 | 1.0000 | 0.3571 |

| ~fps | 0.3193 | 1.0000 | 0.4765 | 0.5644 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, L.; Yang, W.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B. Integrating the Cross-Border Industrial Chain: An Exploring of Key Configuration of Agricultural Investment in Lancang-Mekong River Region. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083431

Feng L, Yang W, Jin Y, Zhang Y, Li B. Integrating the Cross-Border Industrial Chain: An Exploring of Key Configuration of Agricultural Investment in Lancang-Mekong River Region. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083431

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Lu, Wei Yang, Yan Jin, Yan Zhang, and Bo Li. 2025. "Integrating the Cross-Border Industrial Chain: An Exploring of Key Configuration of Agricultural Investment in Lancang-Mekong River Region" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083431

APA StyleFeng, L., Yang, W., Jin, Y., Zhang, Y., & Li, B. (2025). Integrating the Cross-Border Industrial Chain: An Exploring of Key Configuration of Agricultural Investment in Lancang-Mekong River Region. Sustainability, 17(8), 3431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083431