Abstract

Tourism and recreation are critical components of global economies and are significantly impacted by climate change due to their climate-dependent nature. This study aimed to assess the effects of climate change on outdoor recreation within the tourism sector, as perceived by stakeholders and tourists, through a systematic review. Following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, a comprehensive search of the Web of Science database was conducted, resulting in a systematic review of 42 publications that met the inclusion–exclusion criteria out of a total of 226 publications published between 2007 and 2024. The comprehensive analysis identified four primary themes: vulnerability, adaptation, climate change perception, and tourist behavior. The USA emerges as the most researched country, followed by the UK, Germany, and France. The predominant research methods include regression analysis (37.2%) and thematic analysis (20.9%). Coping behaviors regarding climate change are influenced by various factors, such as geography, participant expertise, the type of activity, and the development levels of countries. Tourists adopt locational, temporal, strategic, activity substitution, and informational coping strategies in response to climate change. Conversely, businesses face challenges like reservation cancellations and mitigate global warming effects by modifying activities and adjusting routes due to rising water levels and drought. Adaptation projects are categorized into research–education, management, policy, behavior change, structural, and technical solutions. Implementing diversification strategies enables businesses to enhance their resilience and reduce environmental vulnerabilities. Additionally, raising awareness among visitors about the consequences of climate change is essential in fostering responsible behavior and promoting sustainable practices. The analysis reveals the lack of a holistic perspective in tourism studies, highlighting the need for projects that involve all stakeholders and support undeveloped and developing countries. Furthermore, it was observed that the perspectives of employees and residents were inadequately addressed in the studies examined.

1. Introduction

The significance of tourism and recreation in global economies is well documented [1]. According to 2019 data, tourism constitutes 4% of the global gross domestic product (GDP). Moreover, its indirect impact on other economic sectors is substantial, as evidenced by its multiplier effect on the supply of goods and services, investments, and public spending [2]. The outdoor recreation industry in the United States contributed a significant amount to the nation’s economy in 2022, with a total contribution of USD 563.7 billion to the GDP and the provision of employment opportunities to 4.9 million individuals, as reported by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis [3]. The prevalence of outdoor recreation among the American populace, defined as individuals aged six and above, is further evidenced by the participation rate of 57.3%, which amounts to 175.8 million individuals [3]. A notable increase of 4.1% in participation rates was observed in comparison to the previous year [4]. This statistical analysis indicates a sustained growth trend, a phenomenon that is believed to have been exacerbated by the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite the growth of outdoor recreation, changes or different risks are predicted due to climate change, such as the increasing frequency of extreme storms, changes in precipitation regimes, and rising maximum temperatures [1].

Climate change is affecting economic conditions around the world, with far-reaching implications for economic growth, productivity, public health, and ecological function [5]. It is expected to have far-reaching impacts at all levels of the tourism system, from the global level to the destination community level, as well as leading to operational changes in individual businesses [6]. Concurrent studies have demonstrated that climate change exerts an influence on the growth rates of national economies, the labor supply, agricultural production, natural systems, and health-related problems [7,8]. Tourism emerges as one of the sectors that affects climate change, especially within the scope of international travel. The changing weather patterns, a consequence of global warming, influence tourists’ decisions regarding vacation times and destinations, thereby altering the appeal of various locations and impacting the financial viability of tourism-based enterprises. A study conducted in Israel demonstrates that an increase in temperature negatively influences local and international tourism decisions, with warmer than normal conditions leading to a decline in tourism levels [9]. In the context of climate change and its impact on outdoor recreation, it is predicted that outdoor activities will become increasingly unfavorable in parallel with the increase in temperature. This increase in temperature is expected to result in a decrease in snowfall and a reduction in the length of winter, while warmer weather is likely to have an impact on the lengthening of the recreation season. This phenomenon is attributed to the earlier snowmelt in spring and the later onset of winter, which will enable access to areas that were previously inaccessible due to snow cover and soil saturation during specific times of the year [10,11]. Consequently, recreation times are expected to increase in some regions and decrease in others. For instance, Canada is projected to experience a favorable shift in its climate, particularly favoring tourism, as indicated by an increase in park visits, golf participation, zoo visits, and more general tourism activities (such as sightseeing and shopping) [12,13]. Conversely, climate change is projected to exert a negative influence on cold-weather activities such as alpine skiing, snowmobiling, winter festivals, polar bear watching, and glacier viewing, which are particularly dependent on snow and ice as the primary climate-forming elements [14,15,16,17]. According to a study conducted in Norway, tourists express a preference for rising temperatures, indicative of global warming, while the projected increase in rainy days is viewed negatively [12]. A similar phenomenon can be observed in the context of golf. According to Nicholls et al. [18], future projections of increased rainfall are anticipated to have adverse effects on the game, potentially leading to diminished customer satisfaction. Conversely, decreased rainfall may exert negative impacts on course conditions and irrigation systems.

The effects of climate change are particularly pronounced in African tourism destinations. Key climate-related challenges facing African tourism include increasing temperatures, flooding, severe droughts, snowmelt, a higher frequency of tropical storms, sea level rises, and coral bleaching. For example, in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, extreme weather events have caused significant damage to infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and accommodation facilities, and have exacerbated human–wildlife conflicts and increased the susceptibility to wildfires. Additionally, disruptions to outdoor tourism activities have negatively impacted the experiences of tourists visiting the reserve [19]. In Zimbabwe, businesses have reported that their primary concerns related to climate change include shortened vacation periods for tourists, delayed facility openings, reduced biodiversity, and decreased capacity utilization [20]. Similarly, a study in Mexico indicated that climate change will affect the timing of demand in the tourism market [21].

Given the wide range of activities that can be developed and carried out in natural areas, different adaptation options are likely to emerge in response to the highly vulnerable status of ecosystems in the face of climate change’s impacts. For example, the reduction in snow cover and the deterioration of mountain landscapes in mountainous areas due to climate change may result in a shorter winter season and a longer summer season. This shift presents a potential opportunity for alternative outdoor activities, such as trekking, hiking, and mountain biking, as part of a diversified outdoor tourism plan [22]. The projected increase in the average temperatures during the peak vacation season, particularly in Mediterranean countries, suggests a potential shift in the demand for outdoor recreation, with a tendency toward northern destinations during the summer months. This indicates the likelihood of an increase in the popularity of mountainous destinations during summer. The shift in the summer season is likely to prompt tourists to adapt their vacation preferences, opting for shorter trips over extended vacations [11].

In the initial stages of the research, it was observed that existing studies on the subject predominantly addressed the issues from either a participant or business perspective. Recognizing this trend, this research aimed to conduct an in-depth analysis from both perspectives to identify and address gaps in the literature. By examining the studies through these dual lenses, this research sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter, highlighting areas that have been underexplored or overlooked. Additionally, this study aimed to illustrate the geographical distribution of the examined research, identify the most commonly used methods, and highlight the key findings related to visitors and businesses. The primary aim was to lay a solid foundation for future research by identifying existing trends and gaps within the current body of literature that has explored the relationship between climate change and outdoor recreation. By critically examining these gaps, this study seeks to highlight areas requiring further scholarly attention and empirical investigation. It also seeks to emphasize the urgency and significance of practical applications by demonstrating to policymakers, destination managers, and all sector stakeholders that the impacts of climate change vary based on the geographical location, income disparities, and attitudes.

2. Theoretical Framework

The Impact of Climate Change on Outdoor Recreation

Outdoor recreation encompasses activities undertaken in natural or green spaces, often as part of daily or weekend routines. These settings include forests, coastal areas, lakes, rivers, mountains, national parks, and other protected landscapes. The range of recreational activities includes both passive pursuits, such as sitting, relaxing, and appreciating the scenery, and active endeavors like skiing, mountain biking, and horseback riding. These activities can be enjoyed individually or in groups [23].

The repercussions of climate change for outdoor recreation and tourism can be categorized into two distinct classes: direct and indirect. Direct impacts are defined as any alteration in one or more climate variables that results in a direct modification in the level, duration, timing, or location of participation in outdoor recreation. Indirect impacts, on the other hand, emerge as a consequence of climate change’s effects on the distribution or quality of the natural and cultural resource base on which outdoor recreation is contingent. A notable example of this is the alteration in the patterns of fall leaf peeping tours, attributable to the migration of tree species such as aspen and maple in response to changing climatic conditions [18].

In Indiana, USA, the direct impacts of climate change include an increase in the number of hot and extremely hot days each summer, fewer mild days, more rain, and less snow. These changes are projected to have impacts such as health-related issues, new infrastructure needs, changes in forests and other recreation areas, and changing consumer attitudes towards travel and recreation. The temperature and humidity negatively affect visitors’ outdoor recreation experiences and create challenges for tourism workers [6]. Climate change is also significantly affecting the lifestyles and livelihoods of local communities living around recreation areas, as it leads to the degradation of grasslands, water scarcity, and yield losses in both agriculture and livestock production. Local communities are vulnerable to climate change because they live on fragile and marginalized lands, are highly dependent on natural resources, and have poor living conditions [24]. Increasing air temperatures have significant impacts, especially on winter recreational activities. For example, the decreasing snow cover in Greenland stands out as the most critical climate-related impact. For the 2100 projection, some destinations are expected to exhibit optimal ski temperatures, while snow cover is expected to decrease with increasing precipitation rates, negatively affecting ski slope conditions [25].

In landlocked countries, concerns about the impacts of climate change on the region are mainly centered on sea level rises, erosion, and possible changes to wildlife habitats [26,27,28]. According to the United Nations Development Programme, Small Island Developing States (SIDS) lost USD 153 billion to extreme weather from 1970 to 2020, compared to the SIDS average GDP of USD 13.7 billion [29]. These impacts are increasingly leading to displacement, with small island states in the Caribbean and South Pacific disproportionately affected relative to their population sizes. The ongoing threat of rising global temperatures and ocean acidification is of particular concern, as these phenomena not only jeopardize the integrity of marine ecosystems, such as coral reefs, but also have the potential to disrupt critical economic activities, including fishing and tourism, as well as exacerbating the threat of storm surges. Furthermore, rising sea temperatures are projected to exacerbate the risks of drought and water scarcity in SIDS. For instance, a study conducted in Tonga revealed elevated levels of destination vulnerability due to the island’s considerable exposure to climate events, pronounced seasonality, constrained livelihood options, challenges in accessing human capital, land availability issues, limited infrastructure, restricted access to water and energy resources, environmental degradation, inadequate governance processes, and the limited capacity of nations to adequately adapt [30].

A number of studies have indicated a correlation between rising temperatures and increased travel times. For instance, Liu [31] utilized short-term temperature fluctuations to ascertain that an increase in temperature results in the augmentation of both the total travel time and the number of trips. The author hypothesizes that, if the temperatures are below 5 °C, then a rise in temperature will result in a decrease in travel in low-temperature regions. Nevertheless, it has been determined that visitors will compensate for the reduced number of trips with a longer travel time. In addition to the travel time, Wilkins et al. [32] investigated the economic impact of temperature increases on regions. The authors investigated the impact of a temperature increase of 1.1 °C and 1.7 °C on tourism expenditures in three destinations in Maine, one of the coldest states of the USA, in both the summer and winter seasons. The study’s findings indicated that the highest spending was observed in the summer months across all three destinations. A decline in spending was observed in the winter months, particularly in two destinations that are popular for winter recreational activities. The study predicted a decline in expenditure at 4.6 °C in all locations during winter, with a subsequent rise as the temperatures rise or fall. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that higher temperatures do not permit outdoor activities such as ice fishing, skiing, and snowmobiling but do allow for other outdoor recreational activities, such as hiking and cycling.

In consideration of the impact of climate change on outdoor activities, it is projected that there will be adverse effects on motorized water activities, motorized snow activities, primitive land use, and trail riding. Conversely, it is anticipated that there will be beneficial impacts on swimming [11,33,34,35]. Furthermore, the projected impacts of climate change on hunting, fishing, and participation in undeveloped skiing differ by region in the western United States, with positive impacts in the Pacific Coast region and negative impacts in the Rocky Mountains region. These variations underscore the significance of the regional context in recreationists’ responses to climate change [35]. For instance, in Austria, it is projected that participation in hiking, cycling, swimming, water sports, air sports, and golf tourism will increase in parallel with the extension of the season. However, it has been determined that changes in fish species compositions will affect fishing due to the loss of attractive species; the risk of falling rocks will affect mountaineering due to permafrost reductions; hiking and cycling will be affected by circulatory stress due to hot weather; and algal blooms due to drought will have negative effects on swimming [11]. According to the IPCC 2022 report, tourism and real estate value declines associated with climate-induced harmful algal blooms have been recorded in the US, France, and the UK.

3. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (2020) guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Figure 1). The study utilized data from the Web of Science (WoS) database. The WoS database is an online platform that offers access to numerous databases, providing reference and citation information from academic journals, conference proceedings, and other documents across various academic fields. It encompasses a collection of over 22,000 peer-reviewed journals, more than 308,000 conferences, and over 151,000 books [36]. The justification for utilizing the Web of Science database in this research lies in its distinction as the oldest, most extensively used, and authoritative source for research publications and citations. It is a selective, well-structured, and balanced database that caters to diverse informational needs, providing comprehensive citation links and enriched metadata. In addition to offering a wide range of search resources and data downloads, WoS is regarded as an effective academic research system for the synthesis of evidence through systematic reviews [37].

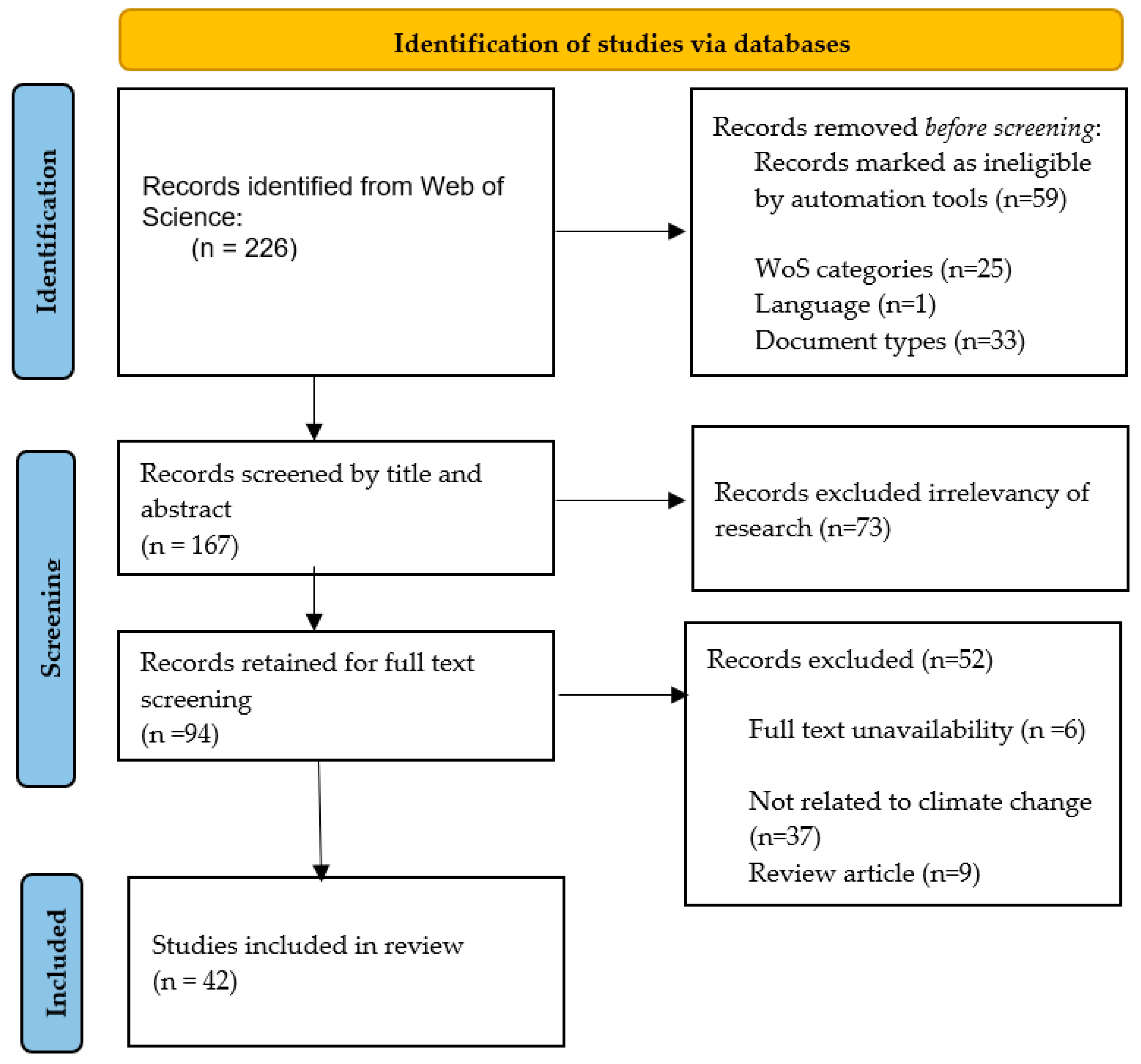

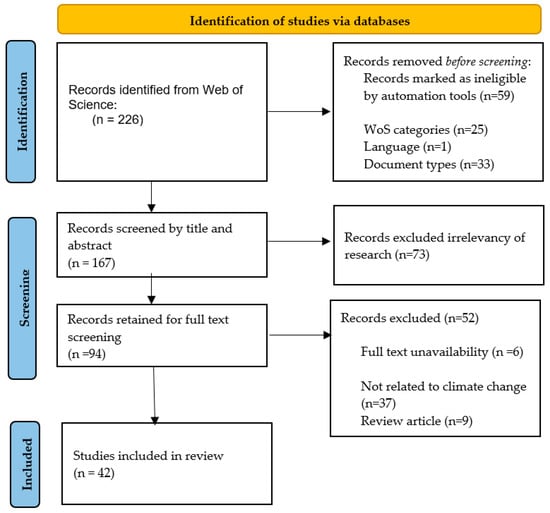

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Source: Page MJ, et al. [38].

Systematic literature reviews are developed within the framework of the specific research questions that they aim to address. Therefore, the research questions (RQs) were initially established.

- RQ1: What is the geographical distribution of the articles?

- RQ2: What are the most common research methods used in the articles?

- RQ3: What is the impact of climate change on outdoor recreation from a visitor perspective?

- RQ4: What are the impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation in the context of businesses?

- RQ5: What are the adaptation strategies implemented in relation to the impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation?

3.1. Search Strategy

The Web of Science (WoS) database was searched on 2 October 2024. The keywords “climate change” OR “global warming” AND “tourism” OR “travel” AND “outdoor recreation” OR “nature-based tourism” were selected as they frequently appear in studies pertinent to the scope of this review paper. The search was conducted without any publication year limitation, and the date range of the publications was 2007–2024. Regarding the eligibility criteria, all publications (n = 226) identified through the search string were initially included for further consideration. Subsequently, the selected publications were evaluated based on exclusion criteria aligned with the research scope.

3.2. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA protocol employed for the selection and exclusion process in this review.

- Initially, 226 publications were identified in the Web of Science database using the search terms “climate change” or “global warming” combined with “tourism” or “travel” and “outdoor recreation”. Automation tools excluded 59 records based on the WoS categories, language, and document types.

- The remaining 167 documents were then screened by analyzing their titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 73 records that were unrelated to the research focus.

- A Microsoft Excel spreadsheet was utilized to compile a list of the remaining 94 articles for full-text screening. This facilitated the systematic categorization of the articles based on their titles, abstracts, problem statements, and research objectives. Documents that were unavailable in full text or not pertinent to the topic were excluded (n = 6).

- Upon reviewing the full texts, several manuscripts were excluded due to their review format (n = 9). The review proceeded with publications that excluded topics unrelated to the impact of global warming on outdoor recreation (e.g., transformative learning theory, coping with COVID-19, forest management) and articles initially excluded but included as reviews in the second evaluation (n = 37).

- Ultimately, after applying the exclusion criteria, a final database of 42 documents was deemed eligible for inclusion in this study.

4. Results

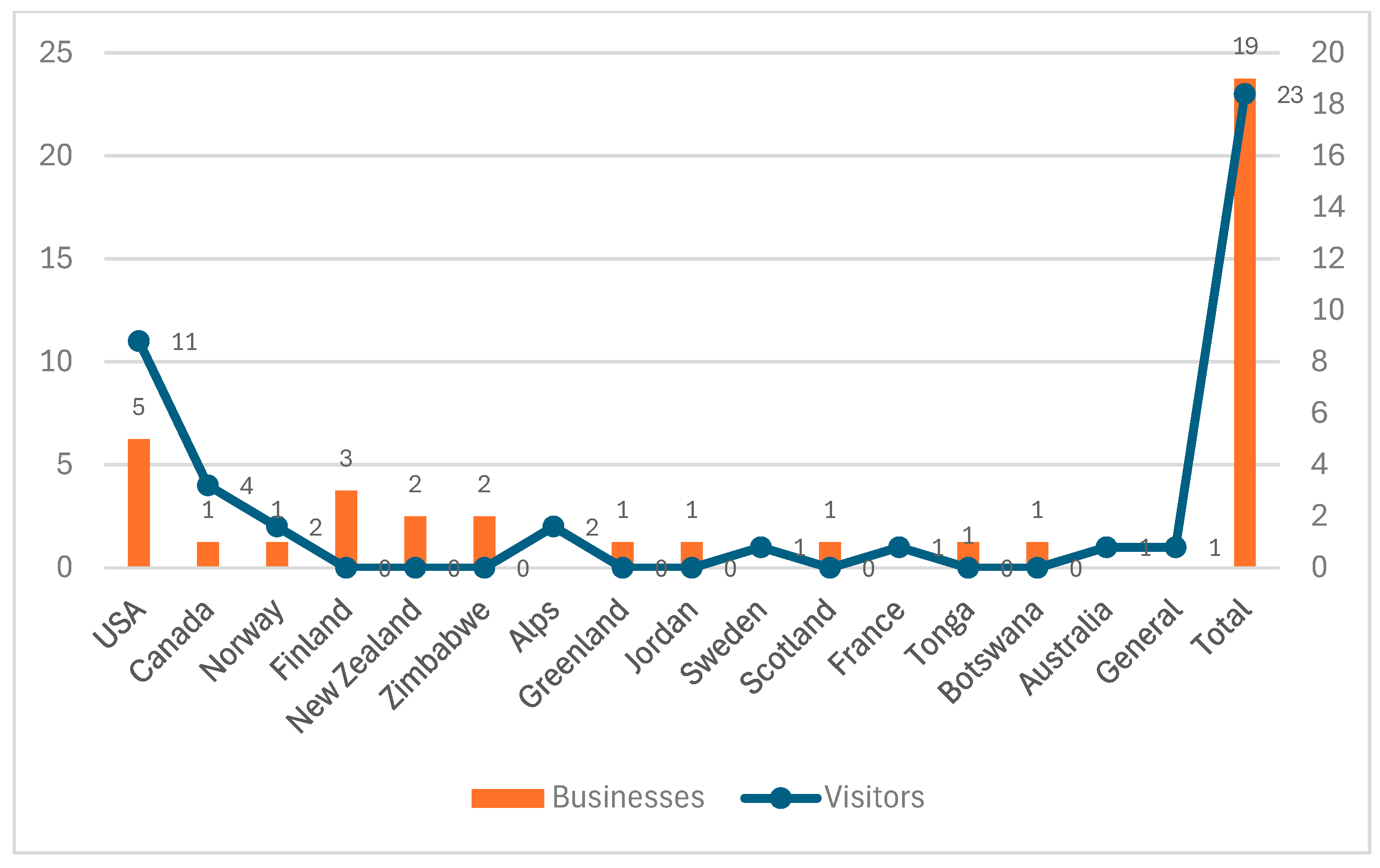

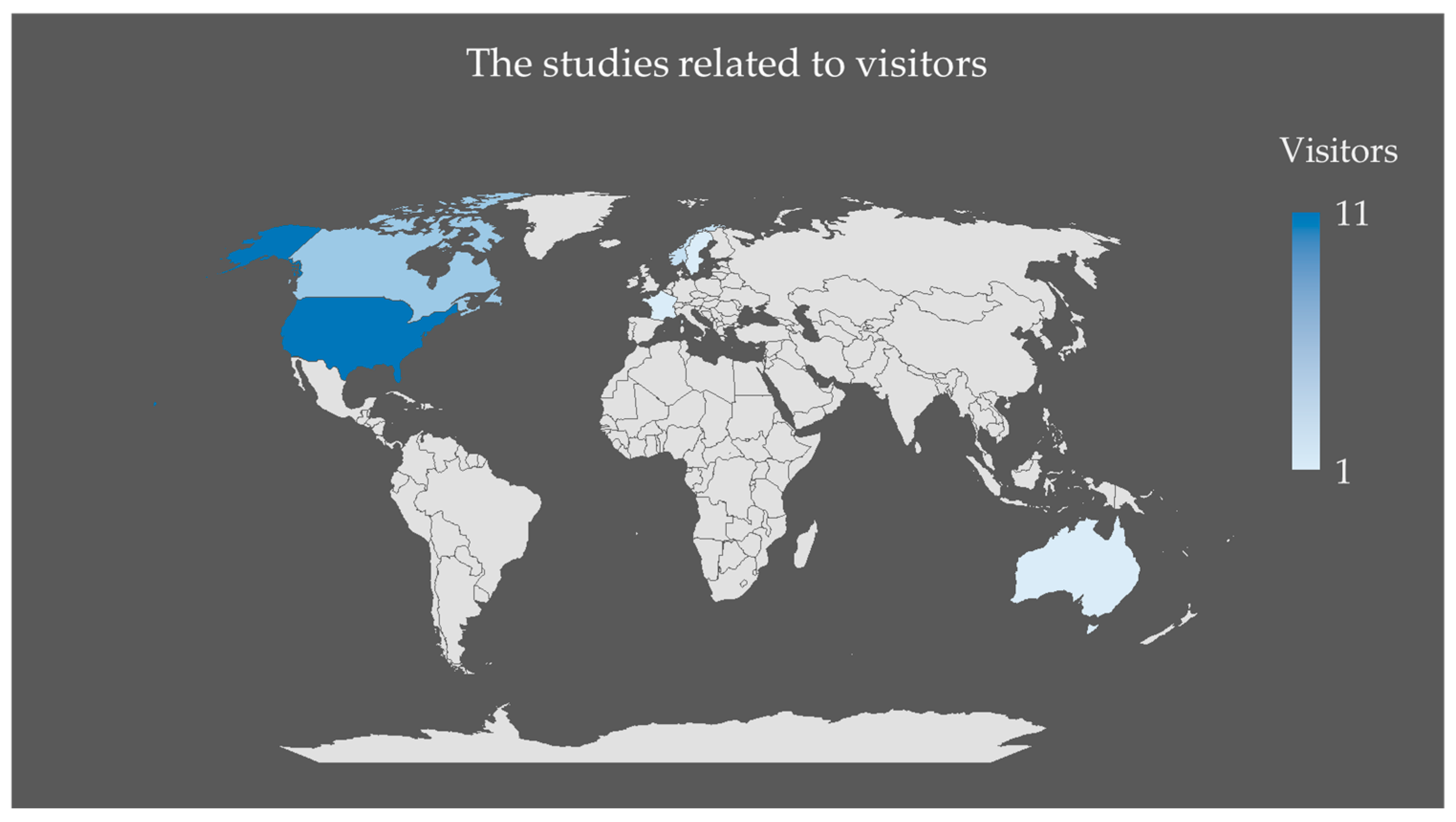

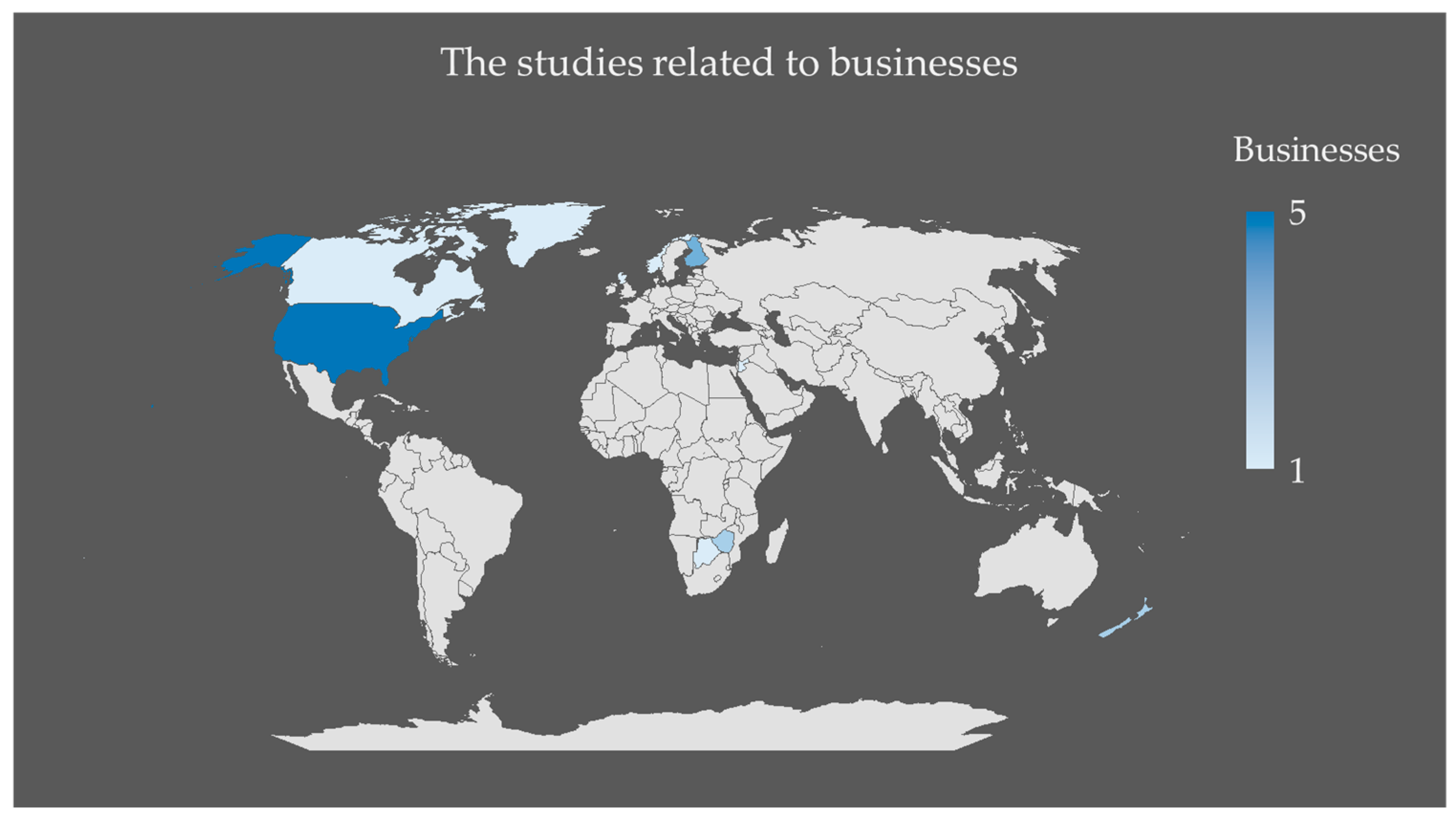

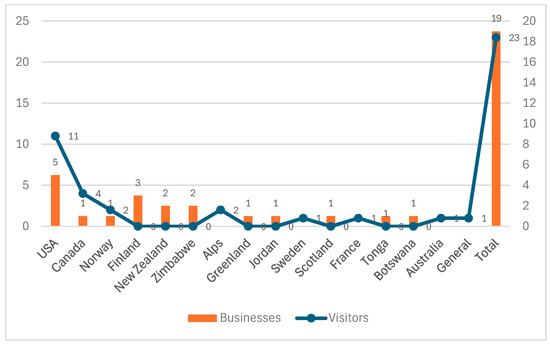

A review of the extant literature reveals that a significant proportion of studies (54.76%) are grounded in a visitor perspective, while 45.24% of articles adopt a business-centric approach to address climate change. A closer examination of the data reveals that the USA dominates as a contributor to both participant- and business-oriented studies (Figure 2). Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate the intensity of research from the visitor and business perspectives, respectively. The outdoor recreation industry contributed approximately USD 640 billion to the GDP in 2023, with the majority of this contribution stemming from travel activities. Non-local travel generated approximately USD 218 billion, while domestic travel contributed almost USD 60 billion. The significance of the outdoor recreation industry in the US is further underscored by the substantial number of visitors to national parks, which reached 326 million in 2023 [39]. Additionally, the Bureau of Economic Analysis conducts regular measurements of the economic activity, sales, and revenues generated by outdoor recreation, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the sector’s productivity. Consequently, it is unsurprising that northern countries such as Canada, Norway, and Finland are the next in line. The 2022 IPCC report indicates a projected risk of the reduced viability of tourism-related activities in North America, increased mass loss of the Greenland and Antarctic Ice Sheets throughout the 21st century and beyond, changes in biodiversity and ecosystem health, and declines in human health and well-being (e.g., tourism, recreation, food, livelihoods, and quality of life). The report indicates that tourism and outdoor recreation are adversely impacted by the decline in snow cover, glaciers, and permafrost in high mountain regions [8].

Figure 2.

Distribution of articles on businesses and visitors by country.

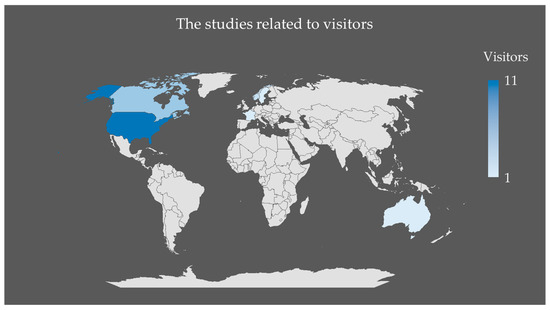

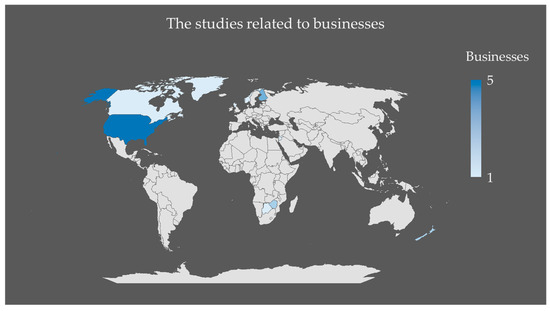

Figure 3.

Studies related to visitors.

Figure 4.

Studies related to businesses.

A similar observation has been made in the context of New Zealand, which has been identified as a country under investigation due to the significant impacts of climate change on tourism, as evidenced by the sector’s heavy reliance on natural heritage and outdoor attractions [8]. While global warming is a phenomenon that affects the entire planet, as evidenced by the graph, there is a conspicuous absence of relevant publications from Central and South America. The dearth of climate data, as well as the pervasive issues of poverty and inequality [8], can explain the paucity of research and highlight the necessity for further advancements in scientific knowledge concerning the consequences of climate change and the vulnerabilities and resilience of ecosystems to it. Poverty and inequality significantly diminish the capacity of individuals and communities to adapt to climate change. Limited access to resources constrains the range of adaptive responses available, as most adaptation strategies require substantial resources [8]. Inequality exacerbates this issue by restricting the options for vulnerable populations. The concentration of global research efforts in North America and Europe is primarily due to the ample resources allocated to research in these regions [40]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between income, human development, and investment in research and development [41]. Nations experiencing elevated levels of poverty and inequality frequently face constraints in financial resources allocated to research and development (R&D). These limitations can lead to a reduction in the number of research initiatives, a reliance on outdated technology, and insufficient facilities.

Following an evaluation of the studies in terms of methods, it was found that regression analysis was the most prevalent at 37.2%, with thematic analysis in second place at 20.9%. At 4.65%, both ANOVA and factor analysis were found to be equally ranked third. The methods employed on a single occasion included the Delphi method, the destination sustainability framework, the sensitivity assessment approach, the weather outdoor recreation process model, the Hirham regional climate model, the hierarchical GAM, cluster analysis, MANCOVA, MAXQDA, the random utility model, the t-test, and the case study. Regression analysis is a statistical method used to determine the relationships between a single dependent variable and one or more independent variables. It is commonly applied in forecasting scenarios [42]. The widespread use of regression techniques in this domain can be attributed to the intrinsic connection between climate projections and regression analysis.

4.1. Visitor Perspective

Since perceptions affect policies and decision-making, understanding beliefs and perceptions about climate change is critical to influencing environmental behavior [32]. Therefore, discussing consumer perceptions towards climate change, learning about the impacts of climate on different tourist groups, and predicting possible future behavioral changes will affect policies and strategies. When focusing on global warming and tourism studies, it is seen that the studies are related to three areas: vulnerability, risk perception, and travel behavior from a participant perspective. While visitors’ vulnerability perceptions are high regarding extreme weather conditions, sea level rises, and increased ticks and mosquitoes, in terms of risk perception, visitors are more interested in environmental factors rather than socially related threats. Disease outbreaks and food and water shortages are perceived as the least risky. De Urioste-Stone et al. [27] revealed three segments: skeptics, believers, and cautors. Skeptics, who constitute a small group, saw climate change as a threat but stated that it would not affect their travel decisions. Believers felt that physiological and safety needs, as well as access and health, could affect their travel decisions. Those who were cautious were neutral in their perceptions of the likelihood of global warming’s impacts on wildlife and access factors and were neutral regarding the impact of climate change on their travel decisions [27]. According to McCreary et al. [43], outdoor recreationists exhibit behaviors such as changing their actions, changing their environments, changing their work, or changing how they evaluate the situation in the face of undesirable conditions that prevent them from achieving their goals of obtaining a desired recreational experience. The articles examined in this review were evaluated within the scope of these behaviors.

4.1.1. Site Substitution

Climate change may affect destination selection and substitution due to changes in precipitation in certain locations. For example, insufficient snow depths for skiing may shift visitors to higher-altitude ski resorts or ski operations with snowmaking opportunities [43]. In West Greenland, ski touring and heli-skiing are likely to move to safer snow destinations as the temperature warms [25]. For tent campers, travel behavior (choosing different destinations, postponing travel) is expected to change due to increased precipitation [32]. According to McCreaery et al. [44], visitors characterized by low travel expectations or long travel distances due to climate change are likely to cancel their trips or travel to another location for ideal recreation conditions. According to their research, it was determined that participants who planned to stay in the same destination would engage in a different activity. However, it should be noted that substitute trips may vary depending on recreationist, sociodemographic, and cultural influences [35]. For example, it has been stated that many trips in Austria are influenced by traditions and expectations, such as spring flowers, colorful forests in autumn, wine tasting in local vineyards, and mushroom or chestnut picking [11]. According to a study conducted in Israel, weather-related parameters have a statistically significant effect on national park visits among both domestic and foreign tourists. However, the study also revealed that the magnitude of the effect varies depending on the park and where the visitors come from [9]. In addition, alternative places will not be preferred because they will require high access costs due to distance or it may not be possible to change the timing of the visit [35]. The type of outdoor activity is also likely to affect individuals’ decisions. For example, according to a study conducted on mountain tourists, the first type of tourists will tend to choose a different destination in the future if rockfalls and personal injuries are frequently experienced. The second group, who are familiar with alpine risks, will largely remain “loyal” to the mountains, even under less favorable conditions. The third group, who are interested in an untouched natural environment during mountain tours and show a high level of risk awareness, will tolerate the natural changes in the terrain and will revisit it [11]. According to the study conducted by Scott et al. [45], participants stated that the attractiveness of the Rockies will decrease due to climate change and that they will visit another mountain park in the long term. However, in a study conducted by Pröbstl-Haider et al. [46], who divided alpine travelers into three groups focused on nature, activity, and recreation, they found that the groups had a low likelihood of switching to an alternative destination due to additional sunny days. The increase in sunny days only becomes important for some tourism segments when it is exchanged for other destination qualities, such as outdoor activities, nature experiences, or events. Therefore, it may not be correct to state that relocation will be preferred for every type of tourist.

4.1.2. Activity Substitution

In Indiana, the longer duration of mild weather due to air temperature changes creates opportunities for recreational participation, while the extreme temperatures experienced in the summer season cause heat-related illnesses such as dehydration, fatigue, chest pain, and respiratory failure and increased energy consumption due to heat. At the same time, it is expected that activities such as ice fishing, cross-country skiing, and snowmobiling will be affected by the decrease in snowfall [6]. A study examining the effects of the climate on outdoor recreation behavior through cycling activity, with data from 27 million bicycle trips in 16 North American cities, determined that climate change will have a significant and positive impact on recreation by the mid-century, generating approximately USD 900 million per year in economic gains for cycling alone and USD 20.7 billion per year for total outdoor recreation [5]. Participants who specialize in outdoor activities will tend to continue their activities despite the impacts of climate change. For example, in Austria, those who specialize in fishing, sailing, mountaineering, canoeing, and golf are likely to choose destinations where they can perform their activities despite climate change [11]. Similarly, according to a study by Salim et al. [16], expert climbers pursue the activity with more enthusiasm than beginners and are more open to substituting one activity or place for another. The higher the climbers’ performance, the higher their substitution behavior. According to a study by Wilkins et al. [32], 35.1% of nature-based generalists, 28.2% of nature-based specialists, and 22.2% of non-nature-based climbers reported that they would change their travel or recreation plans due to weather conditions. In a study conducted in Norway, one-quarter of the participants reported that they tended to engage in more indoor activities due to weather conditions [47]. Taking bus or car trips, visiting museums, going for walks, and performing land-based activities instead of ocean-based activities are emerging as substitute activities. However, it should be noted that, for some activities, such as ferry crossing and whale safaris, substitute activities do not exist [48]. Similarly, while it is easier to switch to substitute activities (e.g., traditional climbing instead of rock-based mountaineering) for rock-based activities, ice-based activities are more difficult to substitute due to their more specific nature. Substituting ice-based activities in time is important for informational coping [16]. In a study on the impact of algal blooms in the Baltic Sea, 40% of the participants stated that they had changed their activities because they could not swim often enough [49]. In Scotland, it has been determined that, in seasons with a lack of snow, instead of skiing, year-round touring activities, winter walking in ski areas, mountain biking, the expansion of restaurant and café facilities, concrete sledging, dry ski slopes, and zip-lines can be implemented [50]. Since cross-country skiing and sled dog tours, which require a minimum snow cover depth of 20 to 30 cm depending on the terrain, are sensitive to temperatures, attempts are being made to compensate with climate change tours, where tourists watch retreating icebergs or experience the Greenland Ice Sheet before it disappears. Since a minimum snow cover threshold of 15–30 cm is required for snowmobiling, the use of ATCs that are not dependent on snow has emerged as a suggestion [25].

4.1.3. Temporal Substitution

The frequent occurrence of typhoons or tropical storms due to climate change in coastal areas and intense heat waves cause tourists to experience reductions in comfort and safety. This may cause tourists to be less likely to visit again or to stay in destinations for shorter periods [51]. According to a study conducted in Norway, one-third of summer tourists change their plans depending on the weather conditions. However, it should be noted that the situation may vary for domestic and foreign visitors. For example, three-quarters of domestic visitors adhere to their original plans, while foreign visitors are more likely to change their plans and 5% shorten their stay. This situation shows that weather perceptions differ between cultures and may vary according to the country of residence [47]. In Sweden, due to algal blooms, tourists tend to shorten their stays or choose another holiday destination, while a small portion cancel their vacations [49]. Climbers mostly avoid routes in August due to poor snow and ice conditions and increased rockfall and tend to travel the route at another time [16]. According to a study conducted with guides, guides are trying to adapt to climate change by choosing different climbing routes, changing their locations, changing the daily and seasonal timing of tours, diversifying the services that they offer to their guests, and offering alternative activities when the weather conditions are not suitable for climbing or when the seasons become shorter and more variable. Guides are shifting their focus from goal-based guidance, such as guiding clients to a specific peak, to instructional guidance (offering courses where guests learn technical skills such as crevasse rescue, avalanche safety training, traditional rock climbing placements, etc.) that can be performed in a variety of weather conditions and less hazardous locations [52].

4.1.4. Strategic Substitution

Strategic substitution is defined as a range of behaviors (spatial, temporal, or unrelated to activity substitution) that enable recreationists to overcome uncertain environmental conditions or climate-related constraints. According to McCreary et al. [43], younger visitors in particular expressed a preference for coping with climate change by using new equipment, gear, or technology during their visit. A Norwegian study revealed that, while hot and rainy days are predicted to rise, tourists will not solely rely on climate factors when choosing a destination. Instead, they will take into account the necessary clothing and equipment [12].

4.1.5. Informational Coping

There is a linear relationship between the risk of the activity and informational coping. For example, perceptions of increased rockfall frequencies and volumes significantly and positively explain the adoption of informational coping. Considering that rockfall in August is explained by strong temperature anomalies in the Alps, and rockfall is associated with exceptionally high basement rock temperatures, it seems that climbers tend to seek more information in the event of a heat wave [16]. According to a study evaluating the effects of sociodemographic, cognitive, experience, and sociocultural factors on the risk perceptions of visitors to Acadia National Park, Maine, it was determined that risk perception increased in visitors who were predominantly women, had higher levels of belief in climate change, had more first-hand experience with climate impacts, and had stronger altruistic values. Contrary to the assumption that anxiety and perceived risks increase in parallel with increased climate change knowledge, the researchers determined that knowledge does not affect risk perception [53]. Another study conducted in Maine found that a lack of knowledge about climate change significantly affects the perceptions of the impacts of climate change on tourism. This lack of knowledge can be used as an educational opportunity for managers, who can inform visitors about the current biophysical changes in destinations, the roles of visitors in reducing their carbon footprints, climate-friendly services offered by the park, the adaptation strategies in place, and possible behaviors to encourage [26]. According to the study conducted by McCreary et al. [43], visitors stated that they coped with climate change by paying more attention to weather forecasts before and during recreational visits. A study conducted in Sweden showed that tourists’ previous experiences affected their preferences. According to the study, 68% of the participants who had experienced an algal bloom would return to the same destination, while 18% would not choose the destination. Returning visitors made plans to avoid the months during which algal blooms are at their highest [49].

4.2. Business Perspective

Research has demonstrated that, from a business perspective, the issue of climate change is regarded in terms of health and safety implications, increased operational costs, alterations in tourist behavior, economic impacts, sustainability, and adaptation.

4.2.1. Health and Safety Implications

As global temperatures and precipitation levels rise, an increase in the scope and intensity of public health threats is anticipated. In addition to diseases transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, a prolonged pollen season is anticipated to exacerbate the process for those afflicted with allergies, respiratory disorders, and asthma, as well as leading to an increase in heat-related illnesses such as dehydration, heat exhaustion, and exertional heat stroke [10,11,54]. According to a study conducted in Finland, an increase in sprains, strains, and fractures was observed due to slippery conditions, while differences in tourists’ nationalities caused problems with health insurance and administrative workloads [34].

4.2.2. Increased Operational Costs

Several climate impacts are expected, including changing oceans, ocean acidification, warmer water temperatures, sea level rises, changing fisheries and marine food webs, larger tidal events, more frequent storms causing infrastructure damage, and erosion. Flooding due to sea level rises, tidal events, storms, and heavy rainfall can damage shops and homes and can disrupt transportation. Furthermore, a significant proportion of tourism infrastructure located in coastal areas is susceptible to flooding [7,54]. A study conducted in Zimbabwe revealed that the top concerns of tourism stakeholders pertained to the decline in groundwater levels due to rising temperatures, the collapse of forests, the heightened risk of fires, and the loss of biodiversity due to animal starvation. The potential impact on the Big Five species (lions, leopards, rhinos, elephants, and African buffaloes) in the region is a key concern, as it is anticipated that this will have a detrimental effect on the destination’s attractiveness [7].

Askew and Bowker [47], in their study examining the effects of global warming on participation in outdoor recreation, predicted that snowmobiling and rudimentary skiing (cross-country skiing and snowshoeing)—and, in some regions, motorized water activities, hunting, and fishing—would be negatively affected in parallel with global warming, while horseback riding and swimming on trails would be positively affected. Similarly, Lépy et al. [43] stated that cross-country skiing and husky and reindeer safari trails would be negatively affected in Finland. According to Craig and Ma [48], one form of outdoor recreation that could be positively affected is camping. There are opportunities for camping businesses to benefit from the positive effects of the weather in seasons other than summer. The climate resources for camping and warm-weather nature-based tourism have generally improved in higher-altitude and -latitude locations, while they have decreased in hot and humid regions. For example, in Africa, due to drought and shallow water levels, boat companies have stated that islands emerging due to receding water damage their boats. Boat companies have reported that extreme droughts have rendered slipways ineffective, making it difficult for boats to dock and land easily. In addition, rising temperatures could cause landing and take-off problems for some aircraft types. For example, an Air Zimbabwe aircraft (MA 60) was forced to abort a landing in November 2015 due to concerns that the wheels could burst or engine problems could occur during landing due to temperatures exceeding 40 degrees. Such extreme weather events are critical as they cause industry stakeholders to lose revenue due to reduced occupancy and reduced sales [7].

In a study conducted in Botswana, some tour operators stated that there would be an increase in the number of people preferring to swim in parallel with the increase in temperature, while others emphasized that guest mobility would decrease due to the temperature and that attractions would be affected poor accessibility and appearances. In addition, businesses are concerned that the increase in temperature will cause vegetation problems, wildlife migration, and the drying of water sources [50]. In a study conducted in Zimbabwe, tour operators stated that their navigation experience and prior knowledge of water bodies were vital for their operations during the summer season, when the water levels are low [49]. In addition, creating an early warning system through the media will help in many activities to prevent tourists from entering risky situations due to floods, storms, or extreme heat [11]. Furthermore, when tourism stakeholders work together, it creates strong interpersonal connections within and between suppliers, allowing businesses to leverage their skill sets to accomplish more complex tasks than would be possible when working alone. Partnerships between tourism suppliers and government representatives have made it possible to realize some projects [42].

4.2.3. Alterations in Tourist Behavior

A study conducted in Finland has indicated that businesses are sensitive to other climate variables, including extreme temperatures, precipitation, wind, and snow and ice [34]. A survey of businesses revealed that cancellations due to weather conditions had occurred in three out of the last four winter seasons. The primary weather conditions that led to these cancellations were high temperatures, extremely low temperatures, strong winds, and rain. A notable frequency of cancellations was observed among enterprises specializing in downhill skiing, cross-country skiing, reindeer riding, and ice activities [55].

Horne et al. [40] argue that park managers or tourism stakeholders can instead focus on visitors’ past experiences with the effects of climate change and appeal to their altruistic values, as opposed to directly providing climate change facts to influence visitors’ perceptions and behaviors. In this context, ensuring that visitors comply with park policies and visitor resource use guidelines, maintaining a positive visitor experience in nature-based tourism environments, and protecting the integrity of natural and cultural resources from changes in visitation, such as increasing tourist numbers, are of critical importance.

4.2.4. Economic Impacts

A study conducted in New Zealand on the economic impact of cancellations estimated the economic impacts of flooding and flooding events from Hurricanes Hale and Gabrielle in early 2023 on public conservation lands and waters in the North Island of New Zealand. The study estimated that the aforementioned losses amounted to NZD 65–97 million, with reduced visitor bookings, a reduction in the regional tourism GDP, and reduced business revenues for concessionaires, with extreme weather events being the primary causes. The greatest loss was incurred by private sector companies operating in conservation areas, thereby reinforcing the pivotal role of protected areas in generating economic income and (regional) development through positive ripple effects [56].

4.2.5. Sustainability and Adaptation

A study conducted in Scotland identified that businesses, particularly those in the ski industry, perceive weather variability as the most significant risk, as they require not only sufficient snow depths for activities but also high visibility and low winds [50]. In North America, industry stakeholders emphasize that the decline in skier numbers across the continent is exacerbated by the scarcity of natural snow and high energy and operating costs, engendering a cycle of deep decline that the industry is attempting to reverse. The loss of areas that are unable to adapt to climate change has been demonstrated to result in damage to supply chains and reductions in the ability to cater to all demographics of skiers [57]. It is anticipated that parks, trails, and nature reserves utilized for tourism and recreation will become more challenging to manage in the face of extreme temperatures. A body of research has identified several consequences of this phenomenon, including changes in habitat suitability for plants and wildlife, increased pressure from invasive species, and changes in the timing of biological events that generate tourism [11]. In Canada, an increase in the number of visitors due to rising temperatures and high guest volumes has been observed to have a negative effect on wildlife and human–wildlife interactions, thereby jeopardizing the sustainability of nature-based tourism [13]. A study conducted in Kariba (Zimbabwe) revealed that the decline in the water level of the regional reservoir has led to challenges in electricity generation and supply. The decline in electricity generation has been found to have a deleterious effect on economic activities in energy-deficient countries, leading to a reduction in disposable income and the weakening of local tourism, particularly among small tourism enterprises that lack the capacity to invest in or adopt alternative energy sources [58].

It is important to acknowledge that corporate attitudes towards climate change can be influenced by factors such as their size and industry. For instance, a study undertaken among entrepreneurs in Finland demonstrates that entrepreneurial characteristics, encompassing values and attitudes, can impede or facilitate adaptation. The study posits that the high confidence of entrepreneurs in their survival may result in reactive responses to global environmental change, as opposed to proactive measures. Entrepreneurs representing smaller businesses may have greater flexibility in terms of shorter planning periods and scales of operations. Conversely, this flexibility may also result in reactivity rather than proactivity, as smaller businesses rely on larger businesses to assume a leadership role in target-scale development. Furthermore, the above study determined that small businesses possess a greater understanding of the state of nature than large businesses [59]. In certain destinations (e.g., Canada), to manage the increasing number of visitors in the context of global warming, it is necessary to increase the number of employees in the short term and to set guest limits in the long term, taking into account the seasonal carrying capacity. Furthermore, it is imperative for park managers to develop distinct strategies for each park, considering the variations in the local climate, tourism, and ecological community composition [13].

4.3. Adaptation Projects

Adaptation strategies have been developed with the aim of addressing sustainable recreation under new conditions in a clearer manner by increasing the flexibility of existing programs and practices. These strategies are determined as follows: increasing the usability of existing recreation areas; scheduling the opening of roads, trails, and facilities; creating budget and management strategies that support longer seasons; collaborating with local organizations and landowners to provide recreation management and economic opportunities; and providing recreation access and managing public expectations through effective communication methods. Concurrently with the augmentation of recreation opportunities, particularly during shoulder seasons, there is a necessity to increase personnel and ensure straightforward access to infrastructure [35]. While some effects of the climate on recreation can be mitigated (e.g., improving the quality of a nature center), adaptation to future climate conditions will be necessary. Scott et al. [45] propose five specific adaptation measures applicable to the tourism industry: research and education; policy; behavioral change; business management; and technical solutions. This review evaluates adaptation projects according to Scott’s classification.

- Research and education: In order to increase environmental awareness, the stakeholders of the Dana Biosphere Reserve have identified two environmental education programs targeting students and employees in public and private institutions [24]. Similarly, a study conducted in France suggests that tourists should be educated about environmental issues (such as melting glaciers) to encourage environmentally friendly behavior [60]. With the development of information materials such as maps containing information about typical risks, it is possible to ensure that appropriate time intervals for activities are selected [11]. In order to protect yellow-eyed penguins on the Otago Peninsula, the New Zealand Department of Conservation has implemented volunteer ranger programs and initiatives to educate tourists on appropriate behaviors, such as not being visible in breeding areas and remaining silent [28]. Raising the awareness and knowledge of climate change issues, publicizing appropriate responses, and encouraging tourists to participate in protecting the natural resources that they come to see and use are examples of research and education [30]. While new activities may have unknown effects, climate change affects the ranges, distribution, behavior, phenotypes, and growth of alpine species, indicating a greater need for evidence-based planning, development, and management [57]. Policymakers and stakeholders can respond to risks and threats more quickly by applying big data analytics and technology to predict adverse weather events in both the short and long term [51] so as to reduce the climate change risks. O’Toole et al. [10] identified a recreation menu and adaptation strategies and approaches designed to help managers to make climate-responsive decisions that best fit their goals, constraints, and perceptions of climate risks and opportunities, and they tested this menu on two recreation projects in two national forests in Vermont and California. They identified adaptation tactics that included deactivating snowmobile segments that were not permanently frozen for snowmobile trails, installing barriers to limit access, and allowing the deactivated trails to naturally revegetate. They identified tactics such as rerouting a trail segment for a hiking trail; shielding shorelines to prevent erosion from pedestrian traffic for developed areas; and preserving the upper tree canopy to provide shade from existing snow for backcountry skiing. Concrete adaptation options, as a result of a case study conducted by Halofsky et al. [61], have demonstrated the benefits of science–management collaboration in climate change adaptation. Adaptation to climate change requires systematic monitoring and evaluation to detect changes and determine the success of adaptive management activities. Being aware of the current knowledge about the potential impacts of climate change is important to identify additional ways to incorporate climate change adaptation into management.

- Policy: Policy innovations must be informed by socioeconomic cost–benefit analysis, stakeholder consultation, and policy adjustment to identify ways to balance the dual missions of conservation and visitor use. In their study, Weber et al. [62] proposed that Parks Canada should initiate a process to develop a public transport strategy. This strategy would alleviate traffic (and associated greenhouse gas emissions) and congestion. It would also support climate change mitigation and adaptation activities onsite. The long-term environmental impacts of climate change are not readily apparent, and businesses are less likely to plan for them at the local level. Consequently, adaptations in response to the potential impacts of climate change are more readily addressed by conservation groups, community members, and local government representatives. To illustrate this point, a conservation representative in Otago is planning to change bird-watching habitats by growing a different plant species that would reduce the fire risk in the region, while another conservation organization is planning to shift the distribution patterns of local seabirds as a result of climate change. This would reduce the fire risk of the region during the long-term dry weather patterns associated with the changing climate [28]. The Finnish government is examining preparedness and risk management in various sectors by addressing adaptation-related legislation, strategies, and policies within the scope of the Kokosopu project. The assessment encompasses a range of sectors, including biodiversity, natural resource management, transport, national defense, marine conservation, rescue services, the built environment, water management, social and healthcare, and environmental protection [63]. The enhancement of the institutional capacity and coordination, the devolution of decision-making authorities to various national and local entities, and the establishment of public–private partnerships have been identified as pivotal strategies for governance and policy [30]. A study of ski industry representatives in North America suggests that responding to climate change, increasing industry sustainability, and growing skier numbers are collective action challenges. In response, industry leaders have proposed a range of solutions, including the introduction of recycling programs, investments in renewable energy sources, and the promotion of international carbon tax schemes [57]. The US Forest Service (USFS) has outlined a strategy that includes supporting the planning of recreational infrastructure, raising awareness of potential risks and opportunities for recreationists, ensuring accessibility for disadvantaged communities, and collaborating with communities and partners to address disparities related to climate change and support adaptation [33]. In France, the “Mountain 2” law of 28 December 2016 highlighted the necessity of taking into account various criteria in order to ensure a balanced nature in operations in the development of tourism in mountain areas and especially the creation or expansion of new touristic units [64].

- Behavioral change: In a study conducted in Canada, participants stated that they desired an educational experience that reflected an unspoiled and natural environment and was interwoven with this natural backdrop. A significant proportion of the visitors indicated that acquiring knowledge about glaciers and the impact of climate change on glaciers was a determining factor in their decision to visit the destination [62]. Given the pivotal role of effective climate change communication in enhancing risk awareness and preparedness, there is an imperative for tourism businesses to develop strategic communication messages that will raise awareness and foster adaptability [28]. Awareness of the potential threats and the appropriate responses of employees in a recreation center enables visitors to be informed about the risks that they may encounter, including specific climate-related threats such as harmful and invasive plants, hazardous trees, flash floods, extreme heat, avalanches, strong winds, and storm surges. Furthermore, well-trained employees can encourage authorized institutions to identify hazardous trees and initiate their removal [10]. From the perspective of visitors, those located within close proximity to the travel distance are more inclined to demonstrate climate-friendly behavior; however, they are less likely to express support for climate-friendly management actions. Given the critical role that awareness and concern about climate change play in influencing visitors’ environmentally responsible behavior, it is imperative for national park managers to educate visitors on the merits of environmentally friendly behavior. This can be achieved by offering a superior onsite experience and enhancing environmental sustainability [65].

- Business management: Managers should try to reduce the negative impacts of climate change on the area by rethinking their marketing strategies. Repositioning efforts should be created by marketing different aspects of the destination or region [60]. Craig et al. [66] investigated how the spatial, temporal, and social proximity to weather and climate events and the scale of events or issues affect the understanding of and impact on business outcomes through the Weather–Proximity–Cognition (WPC) framework, seeking to enable businesses to understand how changing short- and long-term weather and climate conditions affect economic outcomes. WPC, a method that can be used by businesses to understand and localize weather or climate change risks and also to increase the impact of participating in adaptive or mitigating efforts, was applied to two campgrounds in Moab and Gatlinburg. The results from the case study revealed that continuous weather variables and weather events with zero to 10-day lags explained between 2.7% and 61.3% of the variability in the daily camp occupancy rate, depending on the geographical location, meteorological season, and camp occupancy type. In a study conducted in Jordan, tourism stakeholders indicated different methods to increase the capacity of tourism facilities to mitigate the impacts of climate change, focusing on adjusting prices during less popular seasons, marketing, implementing environmentally friendly practices, and developing new tourism services and products [24]. In addition, product diversification benefits many local people, allowing for year-round employment opportunities [50]. Another study showed that national park managers need to find a balance between ecological integrity and visitor use, such as limiting commercial tourism development, prioritizing educational material, and preserving ecological integrity [62]. With the decline of yellow-eyed penguins on the Otaga Peninsula, bird-watching operators have attempted to diversify their tourism products to some extent by integrating species such as New Zealand sea lions and newcomers such as royal spoonbills into the birding experience as part of the purposeful diversification of their tourism products [28]. In two destinations in Finland, businesses have initiated measures to address the scarcity of snow, utilizing snowmaking technology, stockpiling resources, and constructing a ski tunnel. Furthermore, they have developed strategies to diversify with alternative indoor activities (such as swimming pools and indoor ball games) [34]. However, it should be noted that the suitability of snowmaking technology is contingent on the climatic conditions. For instance, in Scotland, businesses have reported that they are unable to utilize snowmaking technology due to factors such as high humidity and temperature variations. Furthermore, non-climate risks such as international competition and evolving consumer demands have been identified as factors that may impede investment decisions by businesses [50]. Conversely, in Greenland, the capital-intensive nature of technical applications such as artificial snowmaking has prompted businesses to explore non-snow-dependent activities, such as winter sailing and heli-skiing, as strategies to extend the tourism season and boost volumes [25]. In Botswana and Zimbabwe, businesses have prioritized visitor comfort and marketing objectives rather than climate change, employing swimming pools, air conditioning, and shade as adaptation strategies [7,67]. Tour operators’ most common adaptation strategy regarding summer temperatures is to organize safaris and boat trips in the early morning and at sunset, when the temperatures are lower [58]. In a separate study conducted in Botswana, tour operators indicated that alternative destinations, such as the Central Kgalagadi Game Reserve, could be utilized in instances where the primary destination, the delta, is inundated. The study further revealed that tourism businesses prioritize afforestation and the incorporation of natural airflow structures in their adaptation strategies. In addition, businesses have emphasized the importance of strategies such as increasing the use of renewable energy, developing an environmental management plan focusing on environmental management, the existence of a fully fledged environmental department in the organization, and compliance with government regulations regarding the carrying capacity [67].

- Technical solutions: To adapt infrastructure, technical solutions such as irrigation, artificial pools, artificial canoe routes, the reconstruction of paths and new connections (bridges) in the case of melting glaciers, or the narrowing of nets to provide rockfall protection can be used [11]. To enhance the recreational opportunities in the San Bernardino National Forest, Lytle Creek has initiated a series of measures. These include the relocation of existing infrastructure and facilities to areas with a reduced risk of climate-related damage, the relocation of visitor access from at-risk areas, collaboration with telecommunications companies to provide services such as ridesharing and emergency communication within the canyon, and the raising of public awareness of climate change and its associated risks [68]. Some businesses, such as fishing tour operators on Lake Michigan, have demonstrated the ability to adapt by changing the fish species that they seek in response to changes in climate. Infrastructure enhancements are required at facilities, such as the installation of floating piers, the optimization of stormwater management, and the implementation of shoreline protections [6]. The enhancement of river continuity to facilitate fish migration, in conjunction with the planting of vegetation along riverbanks to improve fish habitats, can contribute to the adaptation of natural conditions [11]. A study conducted in Zimbabwe has revealed that accommodation facilities in proximity to national parks are susceptible to the effects of drought and erratic rainfall. This has led to the adoption of borehole or rainwater storage tanks as a strategy to conserve water. Furthermore, energy-efficient lighting, solar panels, and liquefied petroleum gas for cooking are commonly implemented in all facilities, while the use of xerophytic plants requiring minimal irrigation is favored in landscaping. While some resorts are implementing environmentally sustainable practices such as matting, afforestation, reforestation, and eco-friendly facilities to mitigate the impact of extreme temperatures, others are implementing unsustainable solutions using air conditioning [7]. A study of the Dana Biosphere Reserve in Jordan revealed that businesses have adopted various technical practices, including alternative energy use, rainwater conservation, environmental experimentation, and camera monitoring, to address social, economic, and environmental issues and reduce its vulnerability [24]. The enhancement of technical equipment to ensure the continuity of these activities is identified as a pivotal solution. For instance, the adoption of alternative vessels capable of navigating shallower waters, the utilization of specialized equipment for air sports, and the enhancement of equipment’s resilience to variable wind conditions have been proposed [11]. Despite the existence of vehicle-based glacier tours in Canada, a company has been granted approval to construct a glass-bottomed observation platform as a response to global warming [62]. In a study on agencies organizing birdwatching tours, the decline in yellow-eyed penguins has prompted agencies to devise adaptations, such as observing penguins in their natural habitats, including rehabilitation facilities or remote monitoring with live video providers [28]. According to a study conducted on the websites of outdoor recreation businesses, businesses stated that, by using business leadership in combating climate change and technological innovation to develop sustainable outdoor equipment, the consumption of products can improve recreationists’ outdoor experiences without harming the environment. These companies asserted that they have developed technological innovations with the objective of ensuring that the equipment required by recreationists offers protection to individuals in the outdoors and is sustainable for the environment. The enhancement of equipment’s quality to obviate the necessity for repurchase, the assurance of the repair of used equipment, and the augmentation of recycled plastic in products are strategies that businesses deem significant in the context of sustainability [69].

In certain studies, the participants indicated a greater propensity to allocate additional financial resources toward adaptation strategies that were designed to mitigate the consequences of climate change [15,17]. A Minnesota-based study revealed that individuals who anticipated adverse consequences from climate change were more inclined to allocate additional funds for adaptation measures [15]. A similar phenomenon was observed in a study on the Mendenhall Glacier in the Tongass National Forest, where participants expressed a willingness to pay an average of USD 648 per year to reduce the annual rate of glacier loss to 0.15 km3 over the next 60 years [17]. This suggests that developing destination marketing efforts that increase the importance of negative climate risks may increase the likelihood of visitors accepting climate adaptation funding initiatives. Investment in interpretive programs that enhance knowledge, awareness, and self-efficacy regarding the impacts of climate change can empower visitors with destination heritage and encourage commitment to make substantial investments in climate adaptation initiatives [15].

A study evaluating the perspectives of Canadian mountain guides on climate change identified several barriers to adapting to climate change within the sector. These included a lack of political leadership, the cost of implementation, a lack of sufficient sector-specific knowledge, limited capacities, a lack of company leadership, and resistance from customers. In addition to the aforementioned factors, other barriers have been identified, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the remote nature of the sector, a perceived lack of urgency, a paucity of action at multiple levels (global, national, local), uncertainty regarding effective adaptation strategies, resistance from employees, and the carbon intensity of the sector [52]. Scrot et al. [25] have stated that ski touring and heli-skiing activities are less sensitive to warming, but heli-skiing contributes to an increase in atmospheric greenhouse gases (high CO2 equivalents per unit income). Furthermore, it is imperative to devise adaptation strategies that are mindful of the sociocultural significance and sustainability of activities such as dog sledding and trophy hunting, which are inextricably linked to Greenlandic traditions. The impact of climate change serves to exacerbate the inequalities already experienced by Indigenous Peoples, Pacific Islanders, migrants, and marginalized populations such as women working in fisheries and mariculture. These inequalities have the potential to undermine livelihoods and food security, increase the risks to basic human rights, and lead to the loss of social, economic, and cultural rights. To mitigate these adverse outcomes, it is imperative to guarantee the rights of access to and utilization of resources and territories for all ocean-dependent communities. Furthermore, the promotion of fair, participatory, and equitable decision-making processes is crucial [8].

Despite the implementation of adaptation strategies, the achievement of the desired or expected results may not be guaranteed. For instance, in the Arctic, external migration was initiated in response to the imminent threat of rising temperatures and the thawing of permafrost. However, this resulted in the loss of livelihoods, infrastructure, and ecosystems. Conversely, in Africa, the integration of plants and animals, the management of soil fertility, the cultivation of diverse plant life, the migration of livestock to areas with low pastures in anticipation of drought, and the implementation of various other strategies have contributed to enhancing food security. Conversely, in the Caribbean, the utilization of state aid for hurricanes and storms has been proposed, but this has resulted in the loss of income sources, depletion of assets, and damage to housing and agriculture. In South Asia, measures such as livelihood diversification, the construction of physical barriers, irrigation channels, and physical protection were implemented to mitigate the impacts of landslides and hurricanes. However, the implementation of these measures resulted in adverse consequences, including the loss of life, property, and infrastructure. In South Asia, adaptation projects such as the regeneration of degraded forests against drought, landslide, and typhoon threats, product diversification, and food aid have resulted in food security, the loss of crops and land, and the pollution of drinking water. The melting of glaciers on a global scale has resulted in migration, the loss of cultural heritage as a result of new livelihood projects, the loss of life, and the loss of income [8].

5. Discussion

In the initial phase of this research project examining the impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation, the study was designed to encompass the perspectives of employees, visitors, and businesses. However, a subsequent analysis of the publications sourced from the WoS database revealed a restricted focus, with studies primarily addressing two perspectives. As a result, this review concentrated on evaluating the studies within the scope of visitor and business perspectives. This observation underscores a significant gap in the research concerning the impact of climate change on employees within the tourism sector. The scarcity of research in this area is further emphasized by the fact that the topic is predominantly addressed in Rushton and Rutty’s [52] study on the coping strategies of Canadian tour guides in response to climate change.

In recent years, numerous reviews have utilized bibliometric analysis, a widely adopted method in this field. Silva et al. [70] and Qui et al. [71] have specifically explored the impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation through bibliometric analysis. Unlike bibliometric analysis, a systematic review provides a more comprehensive framework, albeit with a smaller number of studies. This contrast highlights the depth and breadth offered by systematic reviews in understanding the multifaceted effects of climate change on outdoor recreation.

Despite the dual evaluation framework employed in the studies, a clear correlation emerges between the articles and the themes of vulnerability, adaptation, climate change perception, and tourist behavior, as evidenced by the subject distribution. Within the scope of vulnerability, studies have been conducted on destination vulnerability [7,24,30,34], tourists’ sensitivity to climate change [16,47,49,50], and risk perception [27,52,56]. In the context of adaptation, the most extensively researched topics pertain to climate adaptation strategies [25,28,43,58,59]; temporal, activity, location, and strategic substitution [14,16,18,45,46]; and resilience [28,52,57]. In the context of climate change, several studies have examined climate-friendly behavior [15,17,65] and the willingness to pay to mitigate the impacts of climate change [15,17]. Research has also explored the impacts of weather conditions on tourism expenditures [32,56] and recreation experiences [15,43,46,52,54,58,65,67]. Within the scope of visitor behavior, studies have focused on motivation [32,60] and visitor preferences [12,17,43].

The geographical distribution of the analyzed studies is predominantly centered on the United States. This focus may be attributed to the significant role of outdoor recreation as a major industry in the US [39] and the availability of regular data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. However, considering the global nature of climate change’s impacts, the under-representation of other countries in these studies is a critical issue that needs to be addressed.

6. Conclusions

Tourism and global warming can be understood as interconnected phenomena, each influencing and exacerbating the other in significant ways. The expansion and intensification of the tourism industry contribute to the acceleration of global warming, primarily through increased carbon emissions from transportation, accommodation, and related activities. Conversely, tourism, particularly in regions reliant on climate-dependent activities, is highly susceptible to the adverse impacts of global warming. This vulnerability is particularly evident in sectors such as outdoor recreation, a core component of the tourism industry. The increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, rising temperatures, and shifting ecosystems present considerable risks to outdoor tourism activities, threatening both the environmental sustainability of tourism destinations and the economic viability of tourism-dependent regions.

This study aimed to assess the impacts of climate change on outdoor recreation by analyzing articles from the Web of Science database. The findings reveal that most publications are concentrated in the United States, attributable to the significance of outdoor recreation as a major industry and the availability of comprehensive statistical data in the country. The analysis of these publications highlights a predominant focus on research centered on visitors, specifically addressing visitors’ perceptions of climate change, their substitution behaviors, and the influence of climate change on their travel decisions. From a business perspective, studies have examined the effects of global warming on booking patterns, alternative scenarios, and strategies for adapting to the changing climate. A review of the existing literature reveals a significant gap in research concerning the impact of climate change on employees within the tourism industry, with the notable exception of studies focused on tour guides. Research on this group indicates that guides have adopted various adaptive strategies to cope with climate-related challenges, including relocating to different areas, selecting alternative climbing routes, modifying daily and seasonal tour schedules, diversifying service offerings, and introducing alternative activities when adverse weather conditions or unpredictable seasons render traditional climbing excursions unfeasible. Given the crucial role that tour guides play as intermediaries between tourists and the natural environment, their ability to communicate climate-related information positions them as key actors in raising awareness about global warming. Therefore, expanding the research to examine the broader implications of climate change on tourism employees could provide valuable insights into their role as facilitators of climate adaptation and environmental education. Further investigation into how tourism industry workers experience and respond to climate change could enhance our understanding of workforce resilience and inform policies aimed at improving adaptation strategies across the sector.