1. Introduction

With rising demand for food and water, driven by the elimination of widespread famine, epidemic outbreaks and recent wars, energy consumption and the use of non-renewable sources have increased. Therefore, the European Commission has initiated the “Circular economy action plan”, which finds solutions to environmental and social problems [

1,

2]. Agriculture plays a key role in accomplishing sustainability, with one of the main objectives being soil health [

3].

Understanding soil health and fertility helps farmers properly dose fertilizers and nutrients. Thus, it reduces resource loss and potentially negative environmental impacts such as water contamination, leaching, volatilization, greenhouse gas emissions and deterioration of the soil [

4,

5].

In Europe, the total consumption of mineral fertilizers is estimated at 20–25 million tons annually, while organic fertilizers, which are under the influence of sustainability, are estimated to make up 5–10% of the total market (varies greatly from year to year). European agriculture, which includes Croatia, imports large amounts of nutrients through mineral fertilizers [

6]. According to the International Fertilizer Association [

7], the total global consumption of N, P

2O

5 and K

2O was 109,173,000 tons, 44,093,400 tons and 34,656,700 tons, respectively. Around 13,138,657 tons of N are used in Europe, followed by P

2O

5 with 3,111,479 tons and K

2O with 3,742,126 tons [

8]. In Croatia, 88,431 tons of N, 32,415 tons of P

2O

5 and 40,009 tons of K

2O are utilized [

9]. Moreover, it has been reported that 30–35% of these nutrients leach or volatilize from mineral fertilizers [

5,

10]. On the other hand, organic fertilizers, which include a wide range of fertilizers (slurry, animal manure, sewage sludge, household bio-waste, digestate, straw, compost, green manure, food industry waste, meat-and-bone meal, ashes, etc.), are also a source of nutrients for plants [

11,

12,

13]. All of these residual materials can be enhanced through several processing methods. In this way, recycled nutrients from agriculture can be converted into alternative bio-based fertilizers (BBFs) [

14]. This applies in particular to areas with intensive livestock farming, where considerable quantities of animal manure are disposed of [

6].

The main question worldwide is how to convince farmers to replace mineral fertilizers with BBFs. Firstly, farmers should know their environmental benefits as they are derived from renewable resources, making them a more sustainable replacement for conventional mineral fertilizers, which is today’s goal. Secondly, by enhancing soil health, they contribute to the long-term fertility of agricultural lands while also reducing environmental pollution. As mentioned, they align with the principles of the “Circular Economy” by utilizing organic waste materials and promoting resource efficiency, whereby they minimize waste and contribute to sustainable agricultural practices [

2,

3,

7,

15,

16].

The term “BBF” refers to fertilizer products or resources made from waste or derived from renewable biomass-related sources (e.g., digestate) and used either directly or for the production of tailor-made fertilizers (TMFs). TMFs are specifically designed with a composition determined by the end user, using BBFs and mineral fertilizers as primary resources to meet crop requirements, soil fertility status and/or fertilizer management plans. BBF has gained increasing prominence in academic research, where it is used to describe a broad category of bio-derived materials designed to provide essential nutrients to crops [

1,

6,

11,

17,

18].

Farmers’ preferences for BBFs depend on whether the nutrients and organic ingredients meet the needs of the plants, whether the price of the fertilizers is competitive compared to mineral fertilizers and whether they are easy to apply [

17,

18]. Furthermore, the lower price of animal manure should encourage farmers to replace mineral fertilizers with animal manure, if not entirely, then at least partially [

6,

12,

19]. From an economic perspective, BBFs are proving profitable for farmers as they increase nutrient use efficiency (NUE), improve profit margins and reduce dependence on mineral fertilizers [

20]. Bodake and Gaikwad [

21] highlighted several major obstacles, including the lack of agricultural studies, insufficient financial resources, inadequate supply of BBFs in local village centers and limited support from agricultural departments. A study conducted by Malarkodi and Bharathi [

22] highlighted that the lack of knowledge of application methods and uncertainty about results are the main factors hindering wider acceptance of BBFs. Moreover, the use of BBFs is becoming increasingly fashionable as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional mineral fertilizers in agriculture. These are organic, resource-based fertilizers such as animal manure and other biodegradable wastes that have potential environmental benefits and are in line with circular economy themes. In various countries, farmers prefer concentrated BBFs with a guaranteed N content and a lower price compared to mineral fertilizers. Characteristics such as organic carbon content and nutrient release rate are relevant in some places, but not in all [

1,

6]. Farmers in Denmark, for example, demand BBFs with comparable properties to mineral fertilizers, including the safety of N content and sanitation, and are willing to pay up to 50% of the cost of mineral fertilizers [

1]. BBFs can improve soil fertility and agricultural productivity and reduce the environmental impacts associated with mineral fertilizers. For example, algae-based fertilizers have been found to improve soil fertility and productivity without polluting the environment with inorganic pollutants [

23]. Biochar-based N fertilizers have also been shown to improve NUE and reduce greenhouse gas emissions in tropical soils, making them an improved sustainable option [

24]. Other work, e.g., on economic calculations, shows that BBFs can be more profitable for farmers than mineral fertilizers, especially when their ecological impact is taken into account [

25]. Overcoming challenges is a long-term process, but the first step is always key.

Additionally, farmers’ perspectives and their dependence on manure and other farm-sourced nutrients have shifted with the widespread availability of mineral nutrients. They usually strive for mineral sources due to their well-known composition of nutrients unlike varieties of nutrient content in residual materials such as animal manure [

6]. According to Case et al. [

26], farmers considered animal manure waste, but after a fact-based evaluation, their perception of manure changed, acknowledging it as a valuable source of nutrients. With physical, chemical and biological processes, the composition of nutrients can be changed from its original state. This means that the characteristics of nutrient content would improve, more accurate amounts of N would be obtained and much easier usage and storage of these products would be achieved [

6]. In this way, making new bio-based products from renewable sources could increase sustainability in general and become more acceptable to both farmers and markets [

27]. Furthermore, the concept of using BBFs can also serve as a basis for the implementation of integrated farming systems. This does not only concern the future replacement of mineral fertilizers but also the creation of a circular system in arable farming at the regional level that can be adapted to different pedoclimatic conditions. By integrating animal husbandry, crop production and industrial waste management, this approach can optimize energy resources and improve sustainability [

13].

The use of fertilizers in the European Union is strictly regulated by a variety of policies to ensure environmental protection, sustainable agriculture and food security. These policies aim to promote the use of BBFs as part of broader environmental and sustainability objectives. The EU Fertilizer Regulation (2019/1009) sets out harmonized rules for organic fertilizers and BBFs, including digestate and compost. It sets out quality, safety and labeling requirements to promote the circular economy through the recycling of nutrients from organic waste. It also promotes the use of recycled fertilizers, ensuring that they comply with environmental and health standards. The Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC) aims to reduce water pollution by nitrates from agricultural fertilizers and requires member states to designate nitrate vulnerable zones, implement action programs to limit fertilizer use, set maximum nitrogen application rates (170 kg N/ha/year from livestock manure) and promote precision farming to optimize fertilizer use. The EU Circular Economy Action Plan promotes the recycling of nutrients from organic waste (e.g., digestate, sewage sludge), encourages the replacement of synthetic fertilizers with bio-based alternatives and supports innovative fertilizer technologies (e.g., the recovery of struvite from wastewater). The European “Green Deal & Farm to Fork” (F2F) strategy also aims to reduce nutrient losses by 50% by 2030 while maintaining soil fertility. One of the goals is also to reduce the use of synthetic fertilizers by at least 20% by 2030, promote organic farming (25% of agricultural land in the EU by 2030) and support digital agricultural tools (e.g., satellite-guided fertilization). National policies such as the Fertilizer Act (NN 39/2023), the Regulation on the Use of Sewage Sludge in Agriculture (NN 38/2008), the Regulation on the Protection of Agricultural Land from Pollution (NN 71/2019), the Regulation on the Content of the Action Program for the Protection of Waters from Pollution by Nitrates from Agriculture (NN 72/2021) and the act amending the Agricultural Land Act (NN 52/2022) regulate the application of fertilizers by farmers, including regulations on nutrient management, manure application and subsidies for sustainable agriculture, which complement measures at the EU level [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Kurniawati et al. [

38] stated that policy maker engagement is essential to enhance public acceptance, encourage farmer adoption and ensure the availability of BBFs at affordable prices.

In relation to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (and consequently the Green Deal and Farm to Fork strategies), Croatia’s objectives also include ensuring food security, preserving rural areas, protecting the environment through sustainable agricultural practices, preserving biodiversity and adapting to climate change. The Strategic Plan of the Republic of Croatia within the Common Agricultural Policy for the period of 2023–2027 highlights that soil loss and declining fertility due to erosion are significantly higher in Croatia compared to the EU average, with 1 million ha of agricultural land facing a high risk of erosion. According to a monitoring study conducted by the Croatian Agency for Agriculture and Food on the condition of agricultural land in the Republic of Croatia, the humus content of the soils examined is critically low. The results show that 90% of soils have a humus content of less than 3%, while 55.4% of soils contain less than 2% humus [

39]. This is a result of decades of intensive agricultural practices, including the prolonged use of synthetic and mineral fertilizers, pesticides, topsoil removal, insufficient vegetation cover and inadequate use of manure to replenish organic matter in the soil.

This study’s aims are as follows:

- (i)

Investigate current fertilizer use practices among Croatian farmers.

- (ii)

Assess farmers’ preferences and willingness to adopt new fertilizers, particularly BBFs.

- (iii)

Identify key barriers to BBF adoption in Croatia.

Additionally, the study explores how socio-demographic factors and farm characteristics influence the acceptance of BBFs. Given the lack of research on fertilizer use in Croatia, particularly regarding bio-based alternatives, this study seeks to fill a research gap and provide an updated overview of current trends and challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

The questionnaire focused on understanding farmers’ opinions to explore current and future practices related to BBFs as the agricultural sector moves towards greater sustainability. To ensure the reliability and relevance of the survey, agricultural experts including agronomists, scientists and farmers were consulted in the questionnaire design. The questionnaire was tested on around 10 farmers prior to data collection in order to check its comprehensibility and clarity.

Our sample consisted of 203 farmers from Croatia. According to the latest data, there are 161,227 agricultural producers in Croatia [

40] with an average farm size of 8.6 hectares (2023) and a total utilized agricultural area (UAA) of 1,486,053 hectares [

41]. Organic farming accounts for 119,873 hectares or 8.10% of the UAA, including land under conversion [

41]. For the purposes of the study, the authors divided Croatia into two main areas, Continental and Adriatic Croatia (after applying NUTS2 classification). In Adriatic Croatia, according to national databases, there are a total of 50,097 agricultural holdings (AH) or 31% of the total number of AH in Croatia, and in Continental Croatia, there are 111,130 AH or 69% of the total number of AH. The distribution of the sample corresponds to the population distribution: 77% of responses from Continental Croatia compared to 23% of responses from Adriatic Croatia. The sample was purposive.

Data collection took place between 2 January 2021 and 30 April 2021 (due to difficulties in collecting responses, the questionnaire remained open until the end of the year). In order to obtain a purposive sample, the survey was designed to reflect the diversity of farming practices in the country, including differences in farm size, crop type and geographical location.

Farm size: The questionnaire targeted farmers of all sizes, from small family farms to larger commercial farms. Farm size was considered important for understanding how different farm sizes affect attitudes toward BBFs. Larger farms may have more resources to invest in new technologies, while smaller farms may have different barriers or opportunities for adopting BBF.

Crop type: The Croatian agricultural sector is diverse, and different types of crops are grown in different regions (e.g., fruit, vegetables, cereals and vineyards). The survey aimed to involve farmers from all major crop categories to determine whether preferences and barriers to the adoption of BBFs vary by farm type.

Geographical region: Croatia’s agricultural landscape varies from coastal areas to inland plains. To capture the diversity of practices and challenges faced by farmers, the sample was stratified by geographic region. We ensured that major agricultural regions of Croatia (Continental and Adriatic) were represented in the sample.

The questionnaire was created using the Survey Sparrow platform. This data collection method automatically excludes producers lacking internet access and good computer skills. In general, it is quite challenging to collect a large number of responses (especially from farmers) when conducting surveys. In order to obtain a purposive sample, the survey was initially divided into two brainstorming sessions organized as part of a project in Croatia. These sessions served as a first attempt to engage stakeholders, but the response rate was lower than expected. To increase participation, the survey was further disseminated through a combination of online dissemination via specialized agricultural Facebook groups, contacting the consultancy and direct telephone contact with selected farmers from the consultancy’s database. Thanks to the consultancy company, a considerable number of respondents were recruited (203 valid questionnaires in total). Additionally, as it was difficult to reach farmers in the traditional way, the use of online platforms and direct outreach helped increase sample size and diversity. The use of a consultancy enabled access to a wider range of farmers, including those who are not regular users of online platforms. Respondents were assured anonymity and, during the survey, farmers agreed to participate in the survey. On average, the questionnaire took 10 min to complete, but no strict time limit was set so that participants could answer at their own pace.

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part focused on farmers’ current practices regarding the fertilizers they use, the second part focused on farmers’ willingness to use innovative BBFs and farmers’ willingness to pay for this type of fertilizer. The third part examined socio-demographic and farm characteristics. The type of questions varied throughout the questionnaire, comprising mostly closed questions with one or more answer options, a 4-point scale (from very likely to very unlikely) to explore the acceptability of different types of BBFs and open questions to describe limitations in the use or non-use of BBFs.

The questionnaire was developed through a multi-step process to ensure comprehensiveness and consistency with the research objectives. It began with a literature review of relevant research and projects aimed at developing, integrating, testing and validating nutrient management strategies for the efficient recovery of mineral nutrients and other agronomically valuable products (such as organic supplements and biostimulants) from animal manures. This review enabled the identification of key issues and questions related to BBFs. To further refine the survey, internal workshops were held with project partners where stakeholders provided feedback to ensure that the questions were clear, relevant and in line with the project’s aim to develop reliable and safe fertilizers that could be competitive in the European market. These meetings provided valuable insights which, in combination with the results of previous studies, informed the careful formulation of the questions to cover the key areas of interest. The draft questionnaire was then sent to external reviewers from Belgium and the Netherlands, who assessed its clarity, structure and validity. Finally, it was pre-tested to ensure ease of use for farmers.

This thorough design process, which included a literature review, collaboration with experts and iterative testing, resulted in a well-rounded and reliable survey instrument. The questionnaire aimed not only to address the technical objectives of the project but also to identify end users’ preferences and willingness to purchase bio-based and tailor-made fertilizers.

The data were processed using the STATA v. 16 software package. First, descriptive statistics were used to provide a general description of the sample and opinions about current fertilizer practices and willingness to pay for innovative BBFs. In addition, a linear and logistic regression analysis was conducted to discuss three models and, more precisely, which independent variables influence the willingness to accept new fertilizers in general, BBFs in particular and the willingness to pay more for organic and environmentally friendly fertilizers. Each model contained one dependent and seven independent variables, referred to as multiple regression models [

42]. In addition, the authors applied Firth’s penalized logistic regression to models 1 and 2 due to the high prevalence of positive outcomes (more than 85% “yes” for dependent variables), which can bias the maximum likelihood estimates in standard logistic regression [

43]. For Model 3, the method was applied preemptively to avoid potential problems with sampling bias and to ensure consistent and unbiased parameter estimation. The results section highlights any (statistical) differences in the data between the application of linear regression, logistic regression and Firth’s logistic regression. In addition, linear and (Firth) logistic regression was used to test which factors influence the acceptance of different organic fertilizers. A multicollinearity analysis was conducted beforehand, and the variance inflation factor (VIF) and independent (categorical) dummy variables used for the regression analysis are described in

Table 1.

4. Discussion

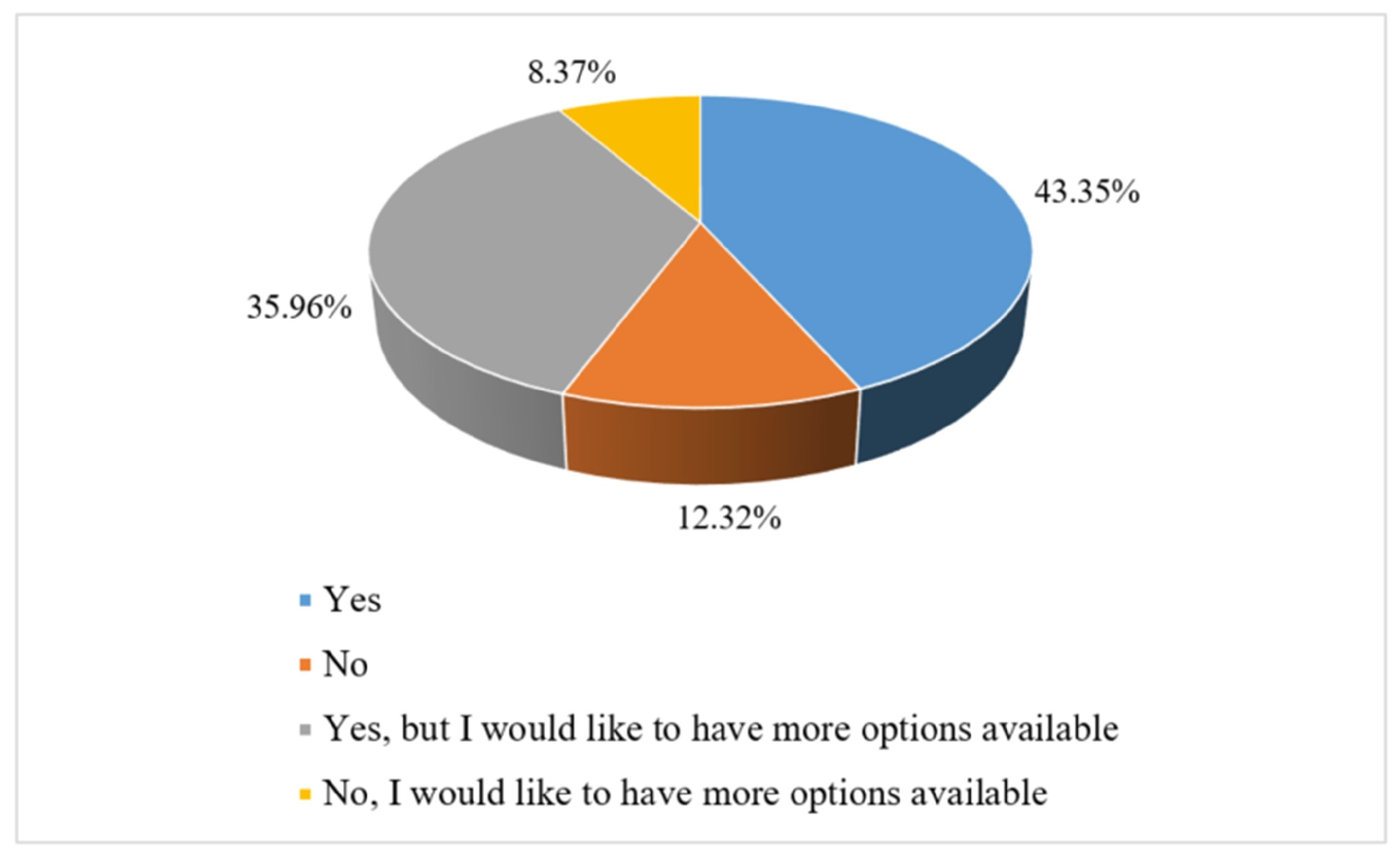

Following the analysis, we can confirm that less than a third of farmers in Croatia use organic practices, which is in line with previous research (e.g., [

45]). Most respondents in Croatia are satisfied or partially satisfied with the supply of fertilizers in general but stated that there is a need for more diverse fertilizer options on the market. In comparison, Tur-Cardona et al. [

6] found that around 40% of respondents were satisfied with the current fertilizer use in the European market. This suggests that the introduction of new products could increase market satisfaction and satisfy unmet needs. We must keep in mind that the market for BBFs is currently smaller and at an early stage compared to the market for conventional mineral fertilizers [

18,

46]. On the other hand, Alvarez Salas et al. [

18] found that the price increase in mineral fertilizers could represent an opportunity for the BBF industry [

47]. The relatively low dissatisfaction rates indicate that most farmers are satisfied, but the desire for diversity points to opportunities for innovation in the fertilizer market, with the aim of protecting the environment. In Croatia, farmers use mineral fertilizers most frequently (32.84%), while only 21.49% use organic fertilizers. In Denmark, for example, 12% of people do not currently use organic fertilizers, while around 80% of them use at least one type of organic fertilizer. Research conducted in Sweden showed that older participants were the most resistant, while younger participants indicated the possibility of using alternative organic fertilizers [

48]. This shows the low level of acceptance of BBFs among Croatian farmers. The comparison of current usage with conventional mineral fertilizers is particularly interesting as it makes it possible to determine the competitive position of the newly developed bio-based alternatives, thus providing useful insights for the design of marketing strategies and policy development [

45].

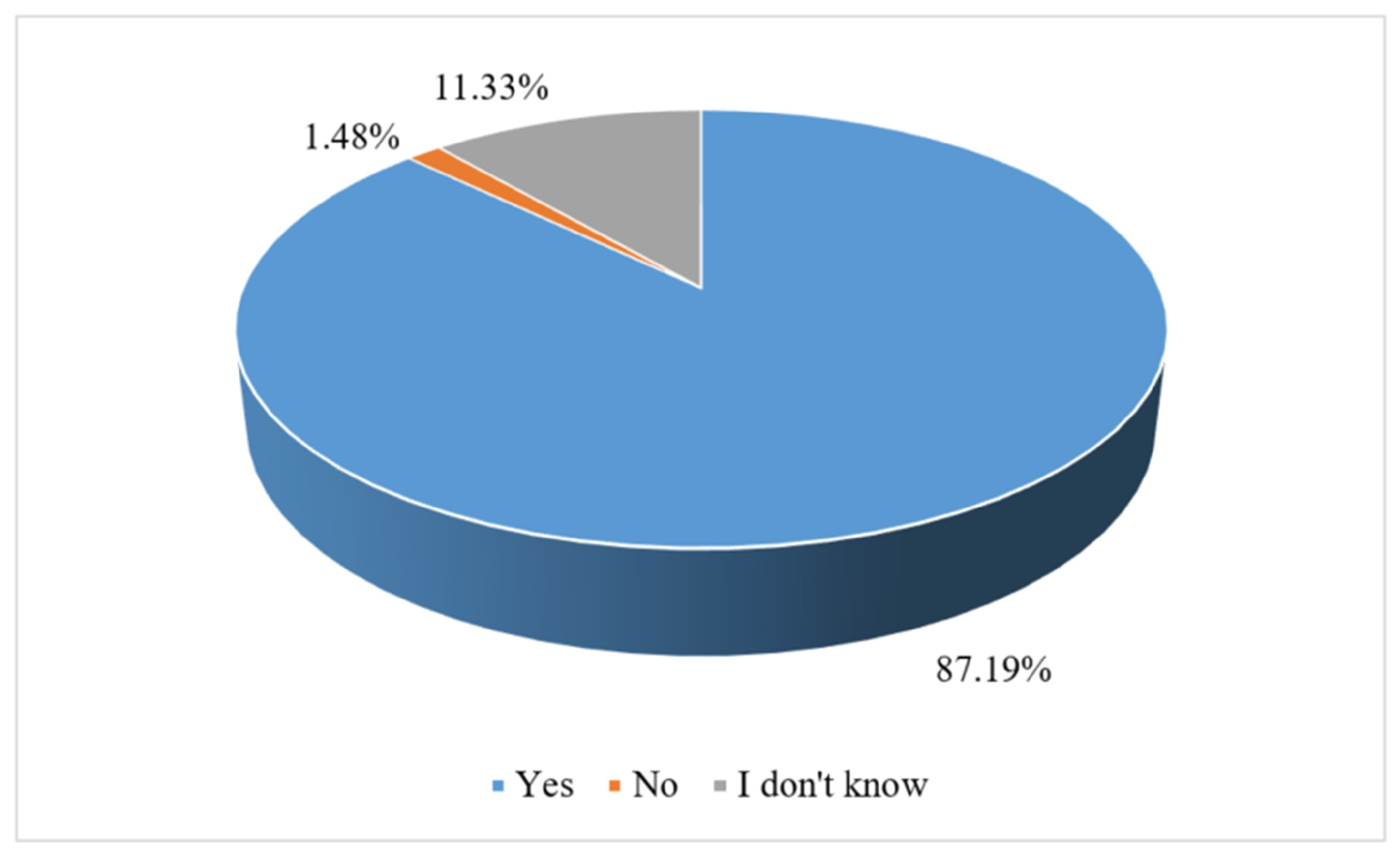

Croatian farmers are generally open to trying new fertilizers, with a clear majority (87%) expressing their willingness to use BBFs due to their positive impact on soil quality, but the lack of availability of alternative organic fertilizers is a challenge. This is consistent with the finding that soil health can be improved through the use of BBFs, as evidenced by another study [

13]. The accessibility and distribution of these fertilizers needs to be improved to meet farmers’ demand and support sustainable agricultural practices. Farmers prefer BBFs from organic and natural sources, such as animal manure and urban green waste. This preference is in line with the findings of Tur-Cardona et al. [

6], according to which 87% of farmers are aware of BBFs in various forms and over 90% of farmers use fertilizers on their fields. However, almost half of these farmers have experienced macro- or micronutrient deficiencies when relying on conventional fertilizers.

Hills et al. [

49] also found that 78% of respondents were already using organic fertilizers, which is consistent with Croatian farmers’ interest in BBFs. Despite this interest, there is a notable gap in the availability of alternative organic fertilizers. While the interest in alternative unprocessed manure and urban waste-derived fertilizer is relatively low (just over 20%), the interest in alternative processed manure is significantly higher, expressed by almost half of the respondents. However, more than two-thirds of farmers interested in alternative organic fertilizers do not have access to them, which is a significant barrier to adoption [

26].

In terms of current fertilizer costs and willingness to pay for BBFs, most farmers pay on average between EUR 200 and EUR 500 annually per hectare. Using the WTP scale, we found that half of the respondents are willing to pay the same price as they do for mineral fertilizers, and only 20% are willing to pay 10% more than the current fertilizer price. Kragt et al. [

50] stated that respondents were highly price sensitive. But, if farmers are more WTP, it is mostly affected by higher incomes and affordable prices of products [

6,

45,

51]. On the other hand, farmers are reluctant due to cost sensitivity, uncertainty about the effectiveness of BBFs and the lack of strong financial incentives. While many farmers are open to the use of biofertilizers, only a small percentage are WTP more unless clear economic and productive benefits are demonstrated [

6,

45].

Recent research showed that farmers are WTP a premium for bio-based fertilizers that have certain desirable properties (e.g., granular, solid form, hygienic or containing organic carbon), compared to fertilizers lacking these properties [

6]. According to the same study, the optimal selling price for bio-based fertilizers in Europe is estimated to be 76.6% of the price of equivalent mineral fertilizers with similar nutrient content, taking into account all preferred properties (solid form, consistent volume, reliable nitrogen content, hygienic conditions and rapid nutrient release). In their experiment, Hills et al. [

49] found that respondents preferred the hypothetical BBF alternative with a lower price. But Moshkin et al. [

45] stated that to ensure the rapid adoption of BBFs, a discount of 30–46% compared to mineral fertilizers is required.

Although interest in BBFs is growing among various stakeholders, their adoption is still held back by a mix of financial and technical challenges. High production and transport costs, limited financial incentives and strong competition from conventional mineral fertilizers make BBFs less economically attractive. In addition, inconsistent nutrient levels, the lack of clear regulations and compatibility issues with current agricultural equipment further complicate matters. Concerns about biosafety and negative consumer perceptions add to the reluctance of growers to make the switch [

6,

17,

38].

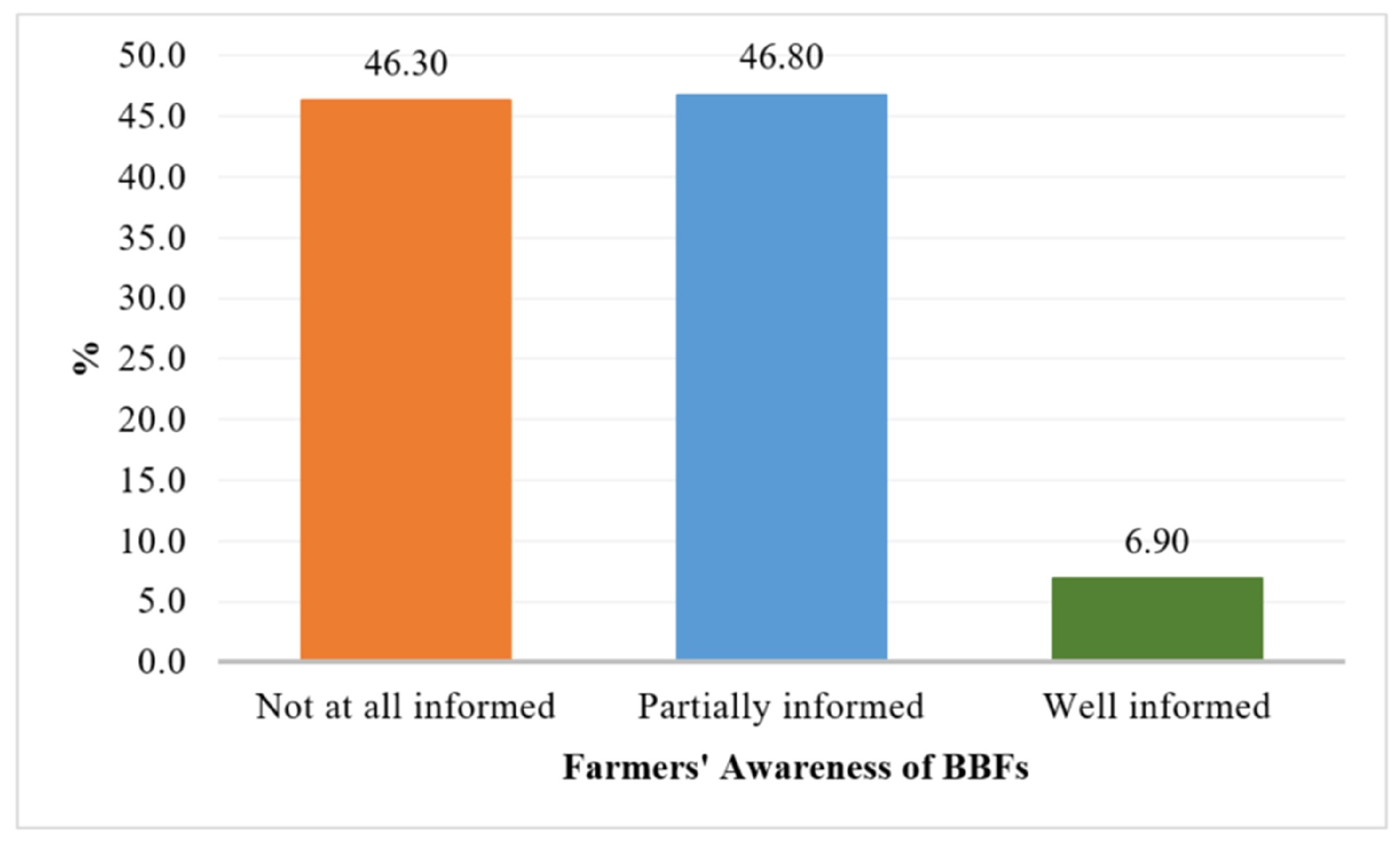

According to the survey results, many farmers feel that they do not have enough information about BBFs, which significantly affects their willingness to use them. Cost is the biggest concern—BBFs are often seen as too expensive, and many also cite the need for specialized equipment as a major barrier. A smaller number of farmers cite regulatory issues and import/export restrictions as additional barriers. Tur-Cardona et al. [

6] also point out that high logistics and production costs may reduce farmers’ willingness to adopt BBF. In addition, some farmers remain skeptical about the actual effectiveness of BBFs, especially in terms of nutrient content.

To make BBFs more attractive to farmers and encourage their wider adoption, some important steps are needed: clearer and more accessible information, better training, financial support, investment in the right equipment, improved regulations and continuous technological development.

From the study of socio-demographic data and farm characteristics, it can be concluded that respondents with an agricultural educational background are more willing to try new fertilizers in general. On the other hand, farms that are organic, in the conversion period and use sustainable practices on the farm are more willing to use bio-based fertilizers and more WTP for bio-based fertilizers. Rachman et al. [

51] stated that farmers with more education are more likely to appreciate the benefits of BBFs and thus are WTP more, which is not consistent with our data. Older farmers tend to resist the introduction of new technologies, relying instead on traditional farming practices and long-standing knowledge acquired over time. A major obstacle to the adoption of BBF technology is the lack of awareness and knowledge of its benefits. Furthermore, implementing BBFs requires additional work and effort, which can be a significant deterrent for older farmers with limited physical capacity. In addition, older farmers often prefer to use animal manure as a fertilizer, as it is a natural by-product of livestock farming and costs little. Its accessibility makes it a convenient and economically viable option, especially for those who are already raising livestock [

18,

46,

52,

53]. Furthermore, the authors concluded that the choice of different organic fertilizers depends on the size of the farm, type of production, higher education and age of the farmer.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the current practices and preferences of Croatian farmers regarding innovative bio-based fertilizers. The results show that although a significant proportion of farmers are aware of BBFs, their use is hindered by factors such as high costs, uncertainty about nutrient content and a strong dependence on conventional fertilizers. Farmers are willing to use BBFs, especially if they have certain desirable characteristics, such as a solid granule form, hygienic conditions and reliable nutrient release. However, the transition to BBFs is also influenced by socio-economic factors such as age, farm size and access to information.

The contribution of this study lies in the assessment of current fertilization practices and farmers’ attitudes towards BBFs in Croatia. The study provides empirical evidence on the factors (high costs, lack of infrastructure and lack of awareness) influencing farmers’ adoption of sustainable fertilization practices and identifies barriers and opportunities for wider adoption. By analyzing farmers’ preferences, the study supports the development of targeted measures, policy interventions, education campaigns and financial incentives to promote BBFs as an alternative to conventional fertilizers. By encouraging collaboration between researchers, policy makers, traders and farmers, Croatia can promote the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices and reduce dependence on mineral fertilizers. In addition, the paper contributes to the growing knowledge of circular economy practices in agriculture, with a focus on the Croatian market.

To avoid financial and logistical setbacks in the implementation of BBF schemes, policy makers should adopt strategic approaches that improve market transparency, financial support and stakeholder engagement. Firstly, the establishment of a central BBF database at the EU level would improve market accessibility by providing up-to-date prices, quality standards and availability, thus promoting informed decision-making. Secondly, targeted financial mechanisms, such as subsidies linked to carbon pricing (connection to agri-food sector) and common agricultural policy (CAP) incentives, would encourage the uptake of BBFs by offsetting higher production costs and rewarding sustainable agricultural practices. In addition, incentives for collaboration between stakeholders, including farmers, industry and researchers, through grants and joint initiatives can increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness. By ensuring clear funding mechanisms and improving the flow of information, these strategies can mitigate economic risks, promote adoption and support the transition to sustainable agricultural practices.

One of the limitations of this study is its geographical scope, as the research was conducted exclusively in Croatia, which may affect the generalizability of the results. In addition, further research should be conducted with farmers who only practice arable farming or horticulture, for example, instead of analyzing farmers in different production areas. Self-reporting by farmers may lead to biases in perception and actual practices. To reduce biases, incorporating a behavioral approach (and using experimental methods) and investigating behavioral and/or psychological factors in future research may help to gain detailed insights into what influences farmers’ preferences for BBFs. Future research should include longitudinal studies and cross-country comparisons as well as long-term field trials to demonstrate the effectiveness of BBF and explore innovative strategies to improve its accessibility and affordability. Ultimately, the switch to BBF is a crucial step towards sustainable agriculture and environmental protection in Croatia.