Sustainable Logistics: Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Intention to Use Toward Autonomous Delivery Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1. What factors influence consumer attitudes toward ADS?

- RQ2. Does consumer attitude affect the intention to use ADS?

- RQ3. Do technology anxiety and personal innovativeness act as moderators in the association between consumer attitude and intention to use ADS?

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Technology Acceptance Model

2.2. Sustainability

2.3. Customer Participation

2.4. Self-Efficacy

2.5. Perceived Risk

2.6. Attitude and Intention to Use

2.7. Technology Anxiety

2.8. Personal Innovativeness

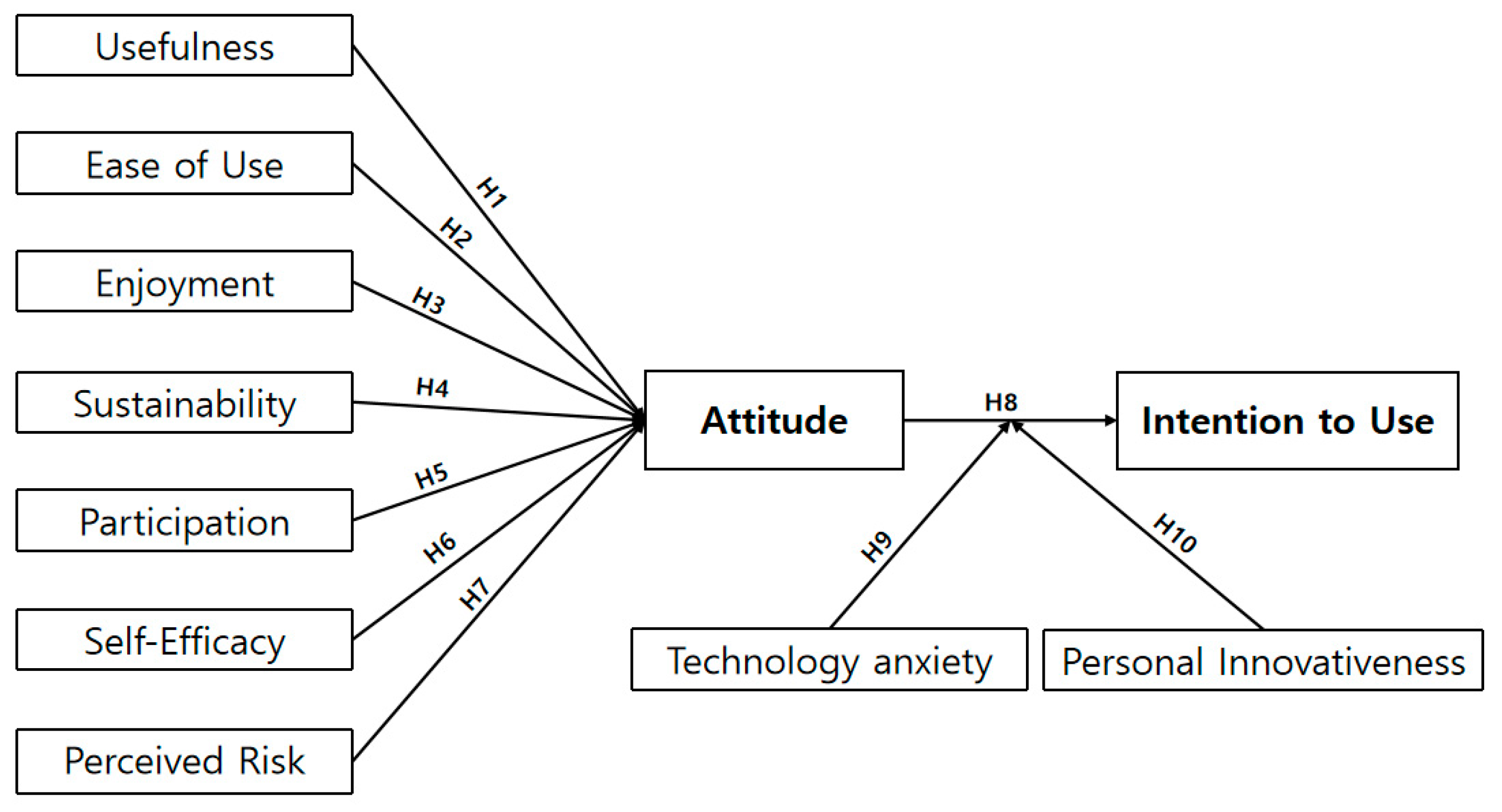

2.9. Research Model

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results of the Analysis

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

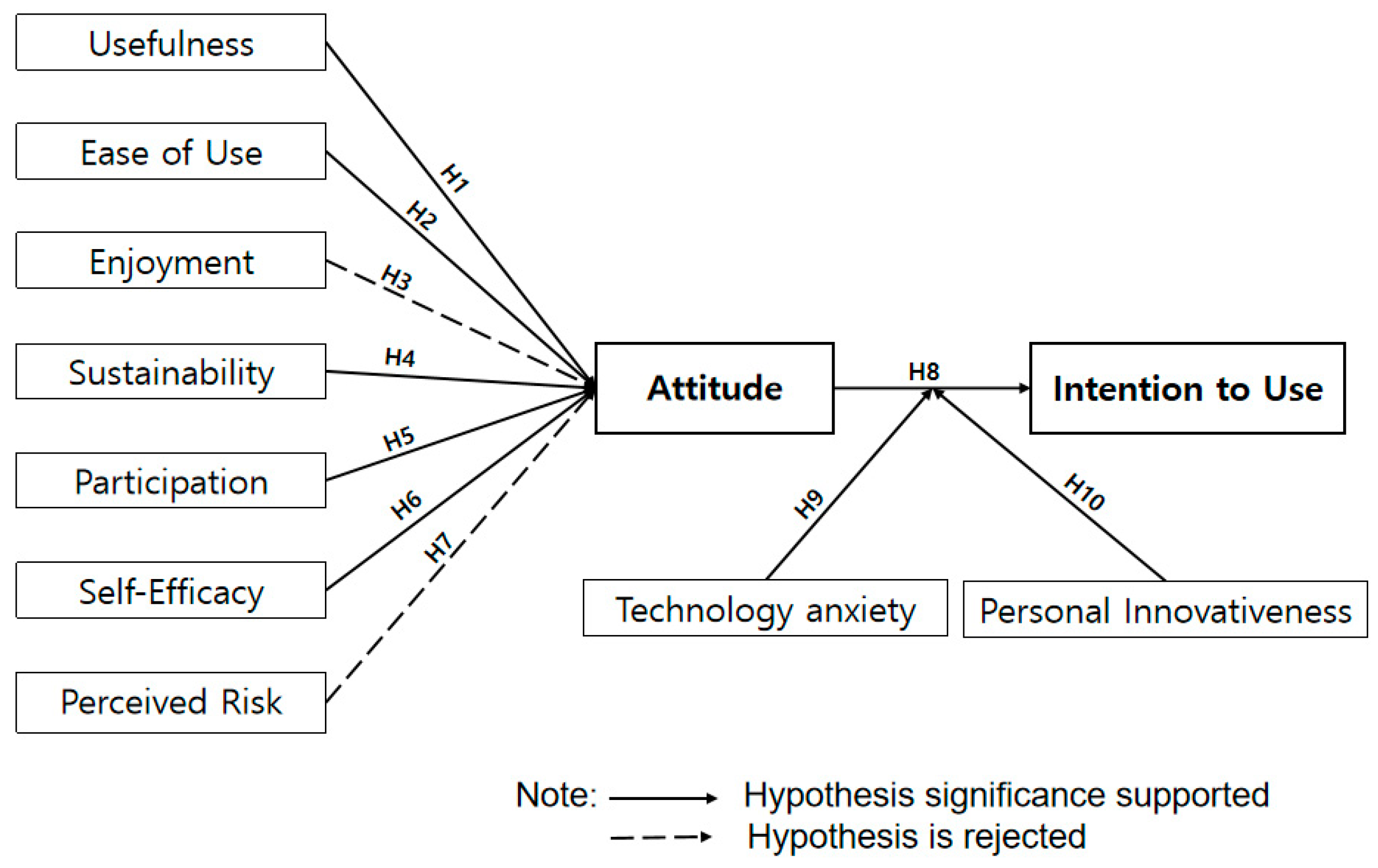

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Multi-Group Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campisi, T.; Russo, A.; Basbas, S.; Politis, I.; Bouhouras, E.; Tesoriere, G. Assessing the evolution of urban planning and last mile delivery in the era of e-commerce. In Smart Energy for Smart Transport; Nathanail, E.G., Gavanas, N., Adamos, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysen, N.; Fedtke, S.; Schwerdfeger, S. Last-mile delivery concepts: A survey from an operational research perspective. OR Spectr. 2021, 43, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranieri, L.; Digiesi, S.; Silvestri, B.; Roccotelli, M. A Review of last mile logistics innovations in an externalities cost reduction vision. Sustainability 2018, 10, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, D.; Figliozzi, M. Study of road autonomous delivery robots and their potential effects on freight efficiency and travel. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R.; Gonzalez, E.S. Understanding the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies in improving environmental sustainability. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorooshian, S.; Khademi Sharifabad, S.; Parsaee, M.; Afshari, A.R. Toward a modern last-mile delivery: Consequences and obstacles of intelligent technology. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2022, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cai, L.; Lai, P.-L.; Wang, X.; Ma, F. Evolution, challenges, and opportunities of transportation methods in the last-mile delivery process. Systems 2023, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogue, R. Strong prospects for robots in retail. Ind. Robot. Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2019, 46, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H. Designing Autonomous Drone for Food Delivery in Gazebo/Ros Based Environments; Technical Report; Binghamton University: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://scholar.smu.edu/engineering_compsci_research/6 (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bogue, R. The role of robots in logistics. Ind. Robot. 2024, 51, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Are Autonomous Delivery Vehicles Classified as Motor Vehicles or Non-Motor Vehicles? Available online: https://www.mot.gov.cn/jiaotongyaowen/202403/t20240304_4039403.html (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- In 2023, the Scale of China’s Low-Altitude Economy Exceeded 500 Billion Yuan. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202402/content_6934828.htm (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Engesser, V.; Rombaut, E.; Vanhaverbeke, L.; Lebeau, P. Autonomous delivery solutions for last-mile logistics operations: A literature review and research agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D. Research on the application of “last-mile” autonomous delivery vehicles in the context of epidemic prevention and control. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Its Application on Media (ISAIAM), Xi’an, China, 21–23 May 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Tu, R.; Lu, T.; Zhou, Z. Understanding forced adoption of self-service technology: The impacts of users’ psychological reactance. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2019, 38, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinders, M.J.; Frambach, R.; Kleijnen, M. Mandatory use of technology-based self-service: Does expertise help or hurt? Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, S.; Elms, J.; Moore, S. Exploring the adoption of self-service checkouts and the associated social obligations of shopping practices. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 42, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Philos. Rhetor. 1977, 10, 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.-W.; Kim, Y.-G. Extending the TAM for a World-Wide-Web Context. Inf. Manag. 2001, 38, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watchravesringkan, K.; Nelson Hodges, N.; Kim, Y. Exploring consumers’ adoption of highly technological fashion products: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivational factors. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2010, 14, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Cheung, C.M.; Chen, Z. Acceptance of internet-based learning medium: The role of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Cheung, C.M.; Chen, Z. Understanding user acceptance of multimedia messaging services: An empirical study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudeyer, P.-Y.; Kaplan, F. What is intrinsic motivation? A typology of computational approaches. Front. Neurorobot. 2007, 1, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Liang, C.; Yan, C.-F.; Tseng, J.-S. The impact of college students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on continuance intention to use English mobile learning systems. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2013, 22, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-S.; Ha, S.; Jeong, S.W. Consumer acceptance of self-service technologies in fashion retail stores. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2020, 25, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijters, B.; Rangarajan, D.; Falk, T.; Schillewaert, N. Determinants and outcomes of customers’ use of self-service technology in a retail setting. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, C.-H.; Hsu, M.K.; Shang, J.-Z.; Wang, S.W. Self-service technology adoption by air passengers: A case study of fast air travel services in Taiwan. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 41, 671–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Du, X.; Zhang, J.; Maymin, P.; DeSoto, E.; Langer, E.; He, Z. Private Vehicle Drivers’ Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles: The Role of Trait Mindfulness. Transp. Policy 2024, 149, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.-S.; Han, S.-L.; Ha, J. The effects of consumer readiness on the adoption of self-service technology: Moderating effects of consumer traits and situational factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, V.; Langella, I.; Carbo, J. From green to sustainability: Information technology and an integrated sustainability framework. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. Integrating sustainability into strategic decision-making: A fuzzy AHP method for the selection of relevant sustainability issues. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C. Corporate social responsibility on customer behaviour: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2020, 31, 742–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldisseri, A.; Siragusa, C.; Seghezzi, A.; Mangiaracina, R.; Tumino, A. Truck-based drone delivery system: An economic and environmental assessment. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C.M.; Albergaria De Mello Bandeira, R.; Vasconcelos Goes, G.; Schmitz Gonçalves, D.N.; D’Agosto, M.D.A. Sustainable vehicles-based alternatives in last mile distribution of urban freight transport: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Yu, E.; Jung, J. Drone delivery: Factors affecting the public’s attitude and intention to adopt. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.O.; Jha, A.N.; Lingappa, A.K.; Sinha, P. Attitude towards drone food delivery services—Role of innovativeness, perceived risk, and green image. J. Open. Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex 2021, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.; Popp, B. Last-mile delivery methods in e-commerce: Does perceived sustainability matter for consumer acceptance and usage? Sustainability 2022, 14, 16437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrisi, A.; Ganjipour, H. Factors affecting intention and attitude toward sidewalk autonomous delivery robots among online shoppers. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2022, 45, 588–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Troye, S.V. Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tat Keh, H.; Wei Teo, C. Retail customers as partial employees in service provision: A conceptual framework. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2001, 29, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.-L.; Song, H.; Han, J.J. Effects of technology readiness on prosumer attitude and eWOM. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2013, 23, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.A. Customer voluntary performance: Customers as partners in service delivery. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Lawlor, J.; Mulvey, M. Customer roles in self-service technology encounters in a tourism context. J. Travel. Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Brown, S.W. Choosing among alternative service delivery modes: An investigation of customer trial of self-service technologies. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.-T.; Yeo, C.; Amenuvor, F.E.; Boateng, H. Examining the relationship between customer bonding, customer participation, and customer satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Wang, J.-P. Customer participation, value co-creation and customer loyalty–A case of airline online check-in system. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barki, H.; Hartwick, J. Measuring user participation, user involvement, and user attitude. MIS Q. 1994, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barki, H.; Hartwick, J. Rethinking the concept of user involvement. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-I.; Chiu, Y.T.; Liu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-Y. Assessing the effects of consumer involvement and service quality in a self-service setting. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2011, 21, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, Y.-J. Do customization programs of e-commerce companies lead to better relationship with consumers? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, P.N.; Shukla, M.K. Examining the Impact of Relational Benefits on Continuance Intention of PBS Services: Mediating Roles of User Satisfaction and Engagement. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2022, 14, 637–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Asaad, Y.; Dwivedi, Y. Examining the impact of gamification on intention of engagement and brand attitude in the marketing context. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Personal and collective efficacy in human adaptation and change. In Advances in Psychological Science: Personal, Social and Cultural Aspects; Adair, J.G., Belanger, D., Dion, K.L., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Locke, E.A. Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blut, M.; Wang, C.; Schoefer, K. Factors influencing the acceptance of self-service technologies: A meta-analysis. J. Serv. Res. 2016, 19, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yun, J.; Chang, W. Intention to adopt services by AI avatar: A protection motivation theory perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 80, 103929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiheydari, N.; Ashkani, M. Mobile application user behavior in the developing countries: A survey in Iran. Inf. Syst. 2018, 77, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-H.; Tang, K.-Y. Investigating factors affecting the acceptance of self-service technology in libraries: The moderating effect of gender. Libr. Hi Tech 2015, 33, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, P.-S.; Lee, K.Y.M.; Ling, L.-S.; Mohd Suhaimi, M.K.A. Investors’ intention to use mobile investment: An extended mobile technology acceptance model with personal factors and perceived reputation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2295603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer behavior as risk taking. In In Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World. In Proceedings of the 43rd Conference of the American Marketing Association, Chicago, IL, USA, 15–17 June 1960; Hancock, R.S., Ed.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1960; pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to influence rural tourism intention by risk knowledge during COVID-19 containment in China: Mediating role of risk perception and attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Zo, H.; Choi, M. User acceptance of wearable devices: An extended perspective of perceived value. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.Y. Exploring perceived risk in building successful drone food delivery services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 3249–3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: A meta-analytic evaluation of UTAUT2. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 23, 987–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; He, L.; Zhu, F. Swarm robotics control and communications: Imminent challenges for next generation smart logistics. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.J.; Jeon, H.M. Untact: Customer’s acceptance intention toward robot barista in coffee shop. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, M.K.; Koay, K.Y. Towards a unified model of consumers’ intentions to use drone food delivery services. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.G.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Lee, D.C. Rule-Based Personalized Comparison Shopping Including Delivery Cost. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2011, 10, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.L.; Sumanth, P.D.; Colling, A.P. A Quantitative Analysis of Possible Futures of Autonomous Transport. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.01696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bonilla, L.; López-Bonilla, J. Explaining the discrepancy in the mediating role of attitude in the TAM. Brit. J. Educ. Technol. 2017, 48, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ryu, M.H. Chinese consumers’ attitudes toward and intentions to continue using skill-sharing service platforms. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Autonomous delivery robots: A literature review. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2023, 51, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastlick, M.A.; Ratto, C.; Lotz, S.L.; Mishra, A. Exploring antecedents of attitude toward co-producing a retail checkout service utilizing a self-service technology. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 337–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuter, M.L.; Ostrom, A.L.; Bitner, M.J.; Roundtree, R. The influence of technology anxiety on consumer use and experiences with self-service technologies. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, N.A.J.; Kabiraj, S.; Shaoyuan, W.; Azam, M.I.A. Adoption of TAM to measure consumer’s attitude towards self-service technology: Utilizing cultural perspectives as a moderator variable. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. The impact of forced use on customer adoption of self-service technologies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeng, M.-Y.; Pai, F.-Y.; Yeh, T.-M. Antecedents for older adults’ intention to use smart health wearable devices-technology anxiety as a moderator. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.-T.; Jabor, M.K.; Tang, T.-W.; Chang, S.-C. Examine the moderating role of mobile technology anxiety in mobile learning: A modified model of goal-directed behavior. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2022, 23, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, K.N.; Le, A.N.H.; Thanh Tam, L.; Ho Xuan, H. Immersive experience and customer responses towards mobile augmented reality applications: The moderating role of technology anxiety. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2063778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giao, H.N.K.; Vuong, B.N.; Tung, D.D.; Quan, T.N. A model of factors influencing behavioral intention to use internet banking and the moderating role of anxiety: Evidence from Vietnam. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2020, 17, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. Diffusion of innovations. In An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research; Stacks, D.W., Salwen, M.B., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2001; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, M.Y.; Fiedler, K.D.; Park, J.S. Understanding the role of individual innovativeness in the acceptance of IT-based innovations: Comparative analyses of models and measures. Decis. Sci. 2006, 37, 393–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirunyawipada, T.; Paswan, A.K. Consumer innovativeness and perceived risk: Implications for high technology product adoption. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. Cultural differences in, and influences on, consumers’ propensity to adopt innovations. Int. Mark. Rev. 2006, 23, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Xie, W.; Tiberius, V.; Qiu, Y. Accelerating new product diffusion: How lead users serve as opinion leaders in social networks. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.E.; Yu, C.-S. Personal innovativeness, social influences and adoption of wireless internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Tian, J.; Liu, Z. Exploring the Usage Behavior of Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Case Study of ChatGPT with Insights into the Moderating Effects of Habit and Personal Innovativeness. Curr. Psychol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.D.; Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, T.M.N. Extend theory of planned behaviour model to explain rooftop solar energy adoption in emerging market. Moderating mechanism of personal innovativeness. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Rehman, U.; Rizwan, M.; Rafiq, M.Q.; Nawaz, M.; Mumtaz, A. Moderating role of perceived risk and innovativeness between online shopping attitude and intention. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.Y.; Qu, H.; Kim, Y.S. A study of the impact of personal innovativeness on online travel shopping behavior—A case study of Korean travelers. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraiwa, S. Voluntary sampling design. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Tiit, E.M. Impact of voluntary sampling on estimates. Pap. Anthropol. 2021, 30, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, C.; Wang, S.; Hu, Z. The impact of individual innovativeness and social influence on consumer intention to adopt autonomous delivery vehicles. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, N.I.; Kasim, H.; Mahmoud, M.A. Towards the development of smart and sustainable transportation system for foodservice industry: Modelling factors influencing customer’s intention to adopt drone food delivery (DFD) services. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.Y.; Xia, Z.; Yuen, K.F. Consumer acceptance of the autonomous robot in last-mile delivery: A combined perspective of resource-matching, perceived risk and value theories. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 182, 104008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Mainardes, E.W. Self-efficacy, trust, and perceived benefits in the co-creation of value by consumers. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 1159–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, Y.C. Exploring university students’ acceptability of autonomous vehicles and urban air mobility. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2024, 115, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, P.Y.K.; Hu, P.J.-H. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: A model comparison approach. Decis. Sci. 2001, 32, 699–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.K.; Huang, H.-L.; Lai, C.-C. Continuance Intention in Running Apps: The Moderating Effect of Relationship Norms. Int. J. Sports Mark. 2021, 23, 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, Y. Crossing the digital divide: The impact of the digital economy on elderly individuals’ consumption upgrade in China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, Z.; Küçük, S.; Karabey, S. Investigating pre-service teachers’ behavioral intentions to use Web 2.0 gamification tools. Particip. Educ. Res. 2022, 9, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yturralde, C.C. Chinese consumers’ satisfaction with online shopping platforms. Asia Pac. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2024, 1, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement Items | References | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | Using an autonomous delivery service will be very useful to me. | [19,27,29] |

| Using an autonomous delivery service will allow me to complete related tasks more efficiently. | ||

| Using an autonomous delivery service will make deliveries faster. | ||

| Using an autonomous delivery service will fulfill my needs. | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) | The process of using the autonomous delivery service will be simple and easy to understand. | [19,27,29] |

| Using an autonomous delivery service will not require much mental effort. | ||

| An autonomous delivery service will be easy to use. | ||

| I will find it easy to learn how to use autonomous delivery services. | ||

| Perceived Enjoyment (PE) | I will feel great enjoyment when receiving packages through an autonomous delivery service. | [26,28,31] |

| An autonomous delivery service will provide me with an enjoyable experience. | ||

| An autonomous delivery service will offer a new and interesting experience. | ||

| Sustainability (SUS) | An autonomous delivery service is an environmentally friendly delivery method. | [38,39,40] |

| An autonomous delivery service has low carbon dioxide emissions in the transportation process. | ||

| An autonomous delivery service contributes to conserving natural resources. | ||

| An autonomous delivery service can help reduce traffic congestion. | ||

| Customer Participation (CP) | I will actively participate in the autonomous delivery service process. | [43,50,103] |

| I will collaborate with the service provider to complete necessary procedures (e.g., providing accurate addresses, setting delivery times). | ||

| I will actively provide feedback to the service provider regarding any issues with the autonomous delivery service. | ||

| I will make suggestions to the service provider for improvements or new features in the autonomous delivery service. | ||

| Self-efficacy (SE) | I am confident that I can easily operate an autonomous delivery service. | [61,64] |

| I am confident that I can use an autonomous delivery service more effectively than others. | ||

| I am confident in my ability to use an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| Perceived Risk (PR) | I am concerned that using an autonomous delivery service may involve certain risks. | [38,41] |

| I am concerned that the safety of an autonomous delivery service may not be guaranteed. | ||

| I am concerned about the risk of personal information leakage when using an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| Attitude (ATT) | I think using an autonomous delivery service is a wise choice. | [38,74,78] |

| I think using an autonomous delivery service is desirable. | ||

| I think using an autonomous delivery service is a good idea. | ||

| I have a positive attitude toward using an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| I think using an autonomous delivery service will be a great experience. | ||

| Intention to Use (ITU) | I am willing to choose an autonomous delivery service. | [31,74] |

| I am more likely to use an autonomous delivery service in the future. | ||

| I will receive products through an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| If given the opportunity, I would like to try an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| Technology Anxiety (TA) | I tend to avoid autonomous delivery technology because I am not familiar with it. | [86,87] |

| I feel anxious about using an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| I worry about whether I can properly use an autonomous delivery service. | ||

| I am anxious that I might make a mistake when using an autonomous delivery service and not receive my product. | ||

| Personal Innovativeness (PI) | I generally adopt new technologies more quickly than those around me. | [27,104] |

| I am willing to try using new technologies and devices. | ||

| I believe learning new technologies is an important personal skill. | ||

| I think new technologies can significantly improve my efficiency and productivity. | ||

| Classification | Category | Number | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 279 | 53.0 |

| Female | 247 | 47.0 | |

| Age | 20–below 30 | 129 | 24.5 |

| 30–below 40 | 157 | 29.8 | |

| 40–below 50 | 118 | 22.4 | |

| 50 and above | 122 | 23.2 | |

| Education | High school/below | 73 | 13.9 |

| University/college graduate | 380 | 72.2 | |

| Postgraduate/above | 73 | 13.9 | |

| Monthly income | Less than 410 USD | 57 | 10.8 |

| 410–820 USD | 148 | 28.1 | |

| 820–1231 USD | 178 | 33.8 | |

| More than 1231 USD | 143 | 27.2 | |

| Frequency of online shopping (including product purchases and food delivery) | Never | 0 | 0 |

| Rarely | 8 | 1.5 | |

| A few times a year | 31 | 5.9 | |

| A few times a month | 167 | 31.8 | |

| A few times a week | 264 | 50.1 | |

| Every day | 56 | 10.7 |

| Variable | Factor | Standard Item Loadings | Cronbach’s α | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | PU1 | 0.816 | 0.873 | 0.634 | 0.874 |

| PU2 | 0.763 | ||||

| PU3 | 0.800 | ||||

| PU4 | 0.806 | ||||

| PEOU | PEOU1 | 0.763 | 0.866 | 0.622 | 0.868 |

| PEOU2 | 0.844 | ||||

| PEOU3 | 0.821 | ||||

| PEOU4 | 0.723 | ||||

| PE | PE1 | 0.776 | 0.849 | 0.655 | 0.850 |

| PE2 | 0.843 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.808 | ||||

| SUS | SUS1 | 0.803 | 0.860 | 0.606 | 0.860 |

| SUS2 | 0.768 | ||||

| SUS3 | 0.772 | ||||

| SUS4 | 0.771 | ||||

| CP | CP1 | 0.815 | 0.893 | 0.676 | 0.893 |

| CP2 | 0.811 | ||||

| CP3 | 0.854 | ||||

| CP4 | 0.809 | ||||

| SE | SE1 | 0.855 | 0.869 | 0.694 | 0.871 |

| SE2 | 0.880 | ||||

| SE3 | 0.760 | ||||

| PR | PR1 | 0.844 | 0.901 | 0.752 | 0.901 |

| PR2 | 0.856 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.901 | ||||

| ATT | ATT1 | 0.778 | 0.915 | 0.685 | 0.915 |

| ATT2 | 0.858 | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.835 | ||||

| ATT4 | 0.769 | ||||

| ATT5 | 0.894 | ||||

| ITU | ITU1 | 0.824 | 0.892 | 0.675 | 0.892 |

| ITU2 | 0.836 | ||||

| ITU3 | 0.826 | ||||

| ITU4 | 0.800 | ||||

| TA | TA1 | 0.756 | 0.868 | 0.622 | 0.868 |

| TA2 | 0.815 | ||||

| TA3 | 0.811 | ||||

| TA4 | 0.771 | ||||

| PI | PI1 | 0.757 | 0.843 | 0.579 | 0.846 |

| PI2 | 0.777 | ||||

| PI3 | 0.718 | ||||

| PI4 | 0.790 | ||||

| Chi-square (χ2) = 935.656, df = 764, χ2/df = 1.225; p = 0.000, GFI = 0.924; CFI = 0.987; AGFI = 0.910; RMSEA = 0.021 | |||||

| PU | PEOU | PE | SUS | CP | SE | PR | ATT | ITU | TA | PI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 0.796 | ||||||||||

| PEOU | 0.425 | 0.789 | |||||||||

| PE | 0.367 | 0.287 | 0.809 | ||||||||

| SUS | 0.371 | 0.433 | 0.336 | 0.778 | |||||||

| CP | 0.282 | 0.372 | 0.309 | 0.329 | 0.822 | ||||||

| SE | 0.307 | 0.387 | 0.253 | 0.361 | 0.255 | 0.833 | |||||

| PR | −0.342 | −0.337 | −0.271 | −0.309 | −0.380 | −0.238 | 0.867 | ||||

| ATT | 0.437 | 0.531 | 0.324 | 0.441 | 0.393 | 0.407 | −0.337 | 0.828 | |||

| ITU | 0.338 | 0.375 | 0.197 | 0.284 | 0.296 | 0.386 | −0.293 | 0.696 | 0.821 | ||

| TA | −0.229 | −0.311 | −0.150 | −0.226 | −0.270 | −0.285 | 0.193 | −0.506 | −0.453 | 0.788 | |

| PI | 0.204 | 0.253 | 0.130 | 0.258 | 0.188 | 0.211 | −0.196 | 0.453 | 0.503 | −0.440 | 0.760 |

| Path | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Path Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: PU→ATT | 0.155 | 0.046 | 3.234 | 0.001 ** | Accepted |

| H2: PEOU→ATT | 0.047 | 0.053 | 5.154 | 0.000 *** | Accepted |

| H3: PE→ATT | 0.265 | 0.045 | 1.048 | 0.295 | Rejected |

| H4: SUS→ATT | 0.132 | 0.045 | 2.710 | 0.007 ** | Accepted |

| H5: CP→ATT | 0.131 | 0.040 | 2.883 | 0.004 ** | Accepted |

| H6: SE→ATT | 0.158 | 0.044 | 3.520 | 0.000 *** | Accepted |

| H7: PR→ATT | −0.059 | 0.042 | −1.320 | 0.187 | Rejected |

| H8: ATT→ITU | 0.699 | 0.056 | 14.344 | 0.000 *** | Accepted |

| Chi-square = 659.292, df = 498, χ2/df = 1.324; p = 0.000, GFI = 0.933; CFI = 0.985; AGFI = 0.920; RMSEA = 0.025 | |||||

| Path | Δχ2, ∆df | Low (n = 281) | High (n = 245) | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | C.R. | Estimate | C.R. | |||

| H9: ATT→ITU | Δχ2 (df = 1) =14.077 *** | 0.789 *** | 12.420 | 0.358 *** | 4.520 | Accepted |

| Path | Δχ2, ∆df | Low (n = 190) | High (n = 336) | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | C.R. | Estimate | C.R. | |||

| H10: ATT→ITU | Δχ2 (df = 1) = 12.761 *** | 0.362 *** | 4.164 | 0.771 *** | 12.397 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Ryu, M.H. Sustainable Logistics: Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Intention to Use Toward Autonomous Delivery Services. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083290

Chen Y, Ryu MH. Sustainable Logistics: Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Intention to Use Toward Autonomous Delivery Services. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083290

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yaxiao, and Mi Hyun Ryu. 2025. "Sustainable Logistics: Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Intention to Use Toward Autonomous Delivery Services" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083290

APA StyleChen, Y., & Ryu, M. H. (2025). Sustainable Logistics: Exploring the Determinants of Consumer Attitudes and Intention to Use Toward Autonomous Delivery Services. Sustainability, 17(8), 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083290