What Constitutes a Successful Livelihood Recovery: A Comparative Analysis Between China and New Zealand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Livelihood Recovery

2.2. Livelihood Recovery Components

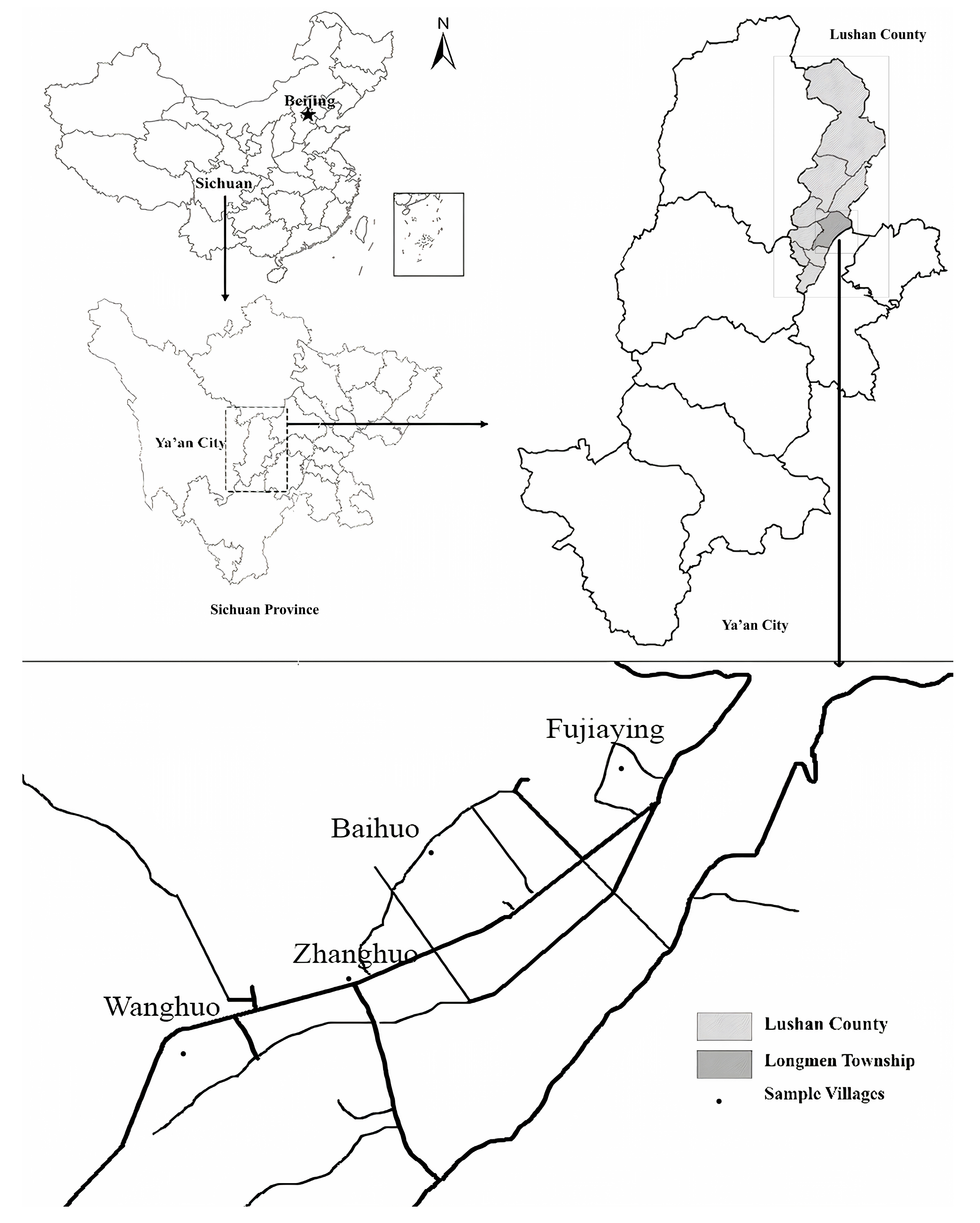

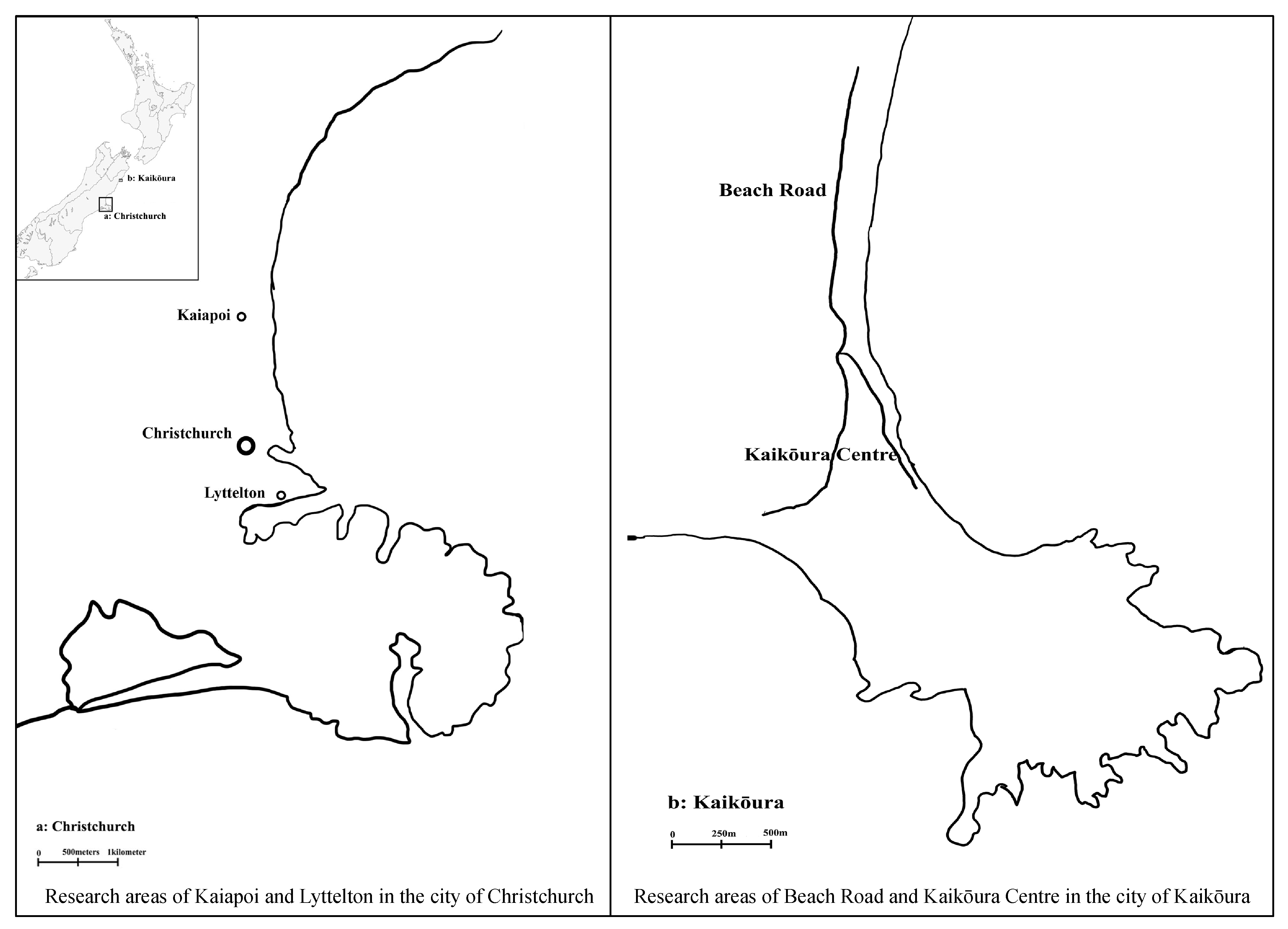

3. Research Methods

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Housing

4.1.1. Housing Functionality

4.1.2. Housing Condition

4.1.3. The Safety and Robustness of Housing

We wanted to start a new business by using one front room for a tea shop. It leaks a lot, and if it rains, it will prevent us from opening the shop.W1

4.1.4. Housing Ownership

4.2. Employment

4.2.1. Income Resources

4.2.2. Access to Employment Opportunities

4.2.3. Education and Skills

Even though we know that education is important, it is too late for us to start learning now.WN3

4.2.4. Work–Life Balance

4.3. External Assistance

4.3.1. Family Assistance

4.3.2. Social Networks

4.3.3. Government Assistance

4.3.4. NGO Assistance

NGO came at the right time to provide advice.KP2

4.3.5. Insurance Policies

Everything needs to be documented: funds, person, and employment, in case such information must be provided to the government. This will enhance efficiency in getting the claim and aim.KP6

4.4. Personal Well-Being

4.4.1. Quality of Life

4.4.2. Livelihood Satisfaction

4.4.3. Physical Health

4.4.4. Mental Health

4.4.5. Feeling of Security

4.5. Summary

5. Recommendations and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaw, R. Indian Ocean tsunami and aftermath: Need for environment-disaster synergy in the reconstruction process. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2006, 15, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Livelihood Assessment Tool-kit. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and International Labour Organization (ILO). Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/tc/tce/pdf/LAT_Brochure_LoRes.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2016).

- Zeng, X.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Zhou, W.; Xu, D. Livelihood risk and adaptation strategies of farmers in earthquake hazard threatened areas: Evidence from Sichuan province, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 53, 101971. [Google Scholar]

- Venn, D. Helping Displaced Workers Back Into Jobs After a Natural Disaster: Recent Experiences in OECD Countries; OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 142; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IDMC. Global Report on Internal Displacement. Available online: https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2019-IDMC-GRID.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Islam, M.R.; Hasan, M. Climate-induced human displacement: A case study of Cyclone Aila in the south-west coastal region of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2016, 81, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What does the future hold for relocated communities post-disaster? Factors affecting livelihood resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 34, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- Pomeroy, R.S.; Ratner, B.D.; Hall, S.J.; Pimoljinda, J.; Vivekanandan, V. Coping with disaster: Rehabilitating coastal livelihoods and communities. Mar. Policy 2006, 30, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, X. Developing a new perspective to study the health of survivors of Sichuan earthquakes in China: A study on the effect of post-earthquake rescue policies on survivors’ health-related quality of life. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2013, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.; Okazaki, K.; Ochiai, C.; Fernandez, G. Livelihood Strategies after the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami in Banda Aceh, Indonesia. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Dietz, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Changes in Human Well-being and Rural Livelihoods Under Natural Disasters. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Liu, S.; Peng, L.; Wang, H. The impact of severe natural disasters on the livelihoods of farmers in mountainous areas: A case study of Qingping Township, Mianzhu City. Nat. Hazards 2014, 73, 1679–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, W.F. Asset building and livelihood rebuilding in post-disaster Sichuan, China. China J. Soc. Work 2013, 6, 190–207. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, Y.; Luo, Y. Post-disaster resettlement and livelihood vulnerability in rural China. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2017, 26, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Fan, J.; Liang, B.; Zhang, L. Evaluation of sustainable livelihoods in the context of disaster vulnerability: A case study of Shenzha County in Tibet, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, Y. A comparative study on the national counterpart aid model for post-disaster recovery and reconstruction: 2008 Wenchuan earthquake as a case. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2013, 22, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Lu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Lau, J. What constrained disaster management capacity in the township level of China? Case studies of Wenchuan and Lushan earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 1915–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J. The progress of emergency response and rescue in China: A comparative analysis of Wenchuan and Lushan earthquakes. Nat. Hazards 2014, 74, 421–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J. NGO collaboration in community post-disaster reconstruction: Field research following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Disasters 2015, 39, 258–278. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Hazeltine, B.; Xu, J.; Prasad, A. Public participation in NGO-oriented communities for disaster prevention and mitigation (N-CDPM) in the Longmen Shan fault area during the Wenchuan and Lushan earthquake periods. Environ. Hazards 2018, 17, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Li, C.; Olshansky, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y. Are we planning for sustainable disaster recovery? Evaluating recovery plans after the Wenchuan earthquake. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 2192–2216. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Xie, Z.; Peng, Y.; Song, Y.; Dai, S. How Can Post-Disaster Recovery Plans Be Improved Based on Historical Learning? A Comparison of Wenchuan Earthquake and Lushan Earthquake Recovery Plans. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, G.; Chang-Richards, A.Y. Identifying critical factors affecting the livelihood recovery following disasters: A comparative analysis of China and New Zealand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 114, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, S.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Beaven, S.; Orchiston, C. Characterising rural resilience in Aotearoa-New Zealand: A systematic review. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 543–557. [Google Scholar]

- Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Fountain, J.; Buelow, F. Transformations for resilient rural futures: The case of Kaikōura, Aotearoa-New Zealand. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, L.J. The livelihood approach: A critical exploration. Erdkunde 2012, 66, 345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.; Boyd, S. Nature-based tourism in peripheral areas: Introduction. In Nature-Based Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development or Disaster? Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, J.R.; Kachali, H.; Whitman, Z.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Wilson, T. Preliminary observations of the impacts the 22 February Christchurch earthquake had on organisations and the economy. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2011, 44, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, S.H.; Becker, J.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Rossiter, K.P. An overview of the impacts of the 2010-2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 14, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, W.J.; Dickson, M.E.; Denys, P.H. New insights on the relative contributions of coastal processes and tectonics to shore platform development following the Kaikōura earthquake. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2017, 42, 2214–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, D.M.; Stevenson, J.; Wotherspoon, L.; Ivory, V.; Trotter, M. The role of data and information exchanges in transport system disaster recovery: A New Zealand case study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 39, 101124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafti, M.T.; Tomlinson, R. Best practice post-disaster housing and livelihood recovery interventions: Winners and losers. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwazu, G.C.; Chang-Richards, A. A framework of livelihood preparedness for disasters: A study of the Kaikōura earthquake in New Zealand. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 61, 102353. [Google Scholar]

- Scoones, I. Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. J. Peasant Stud. 2009, 36, 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, R. What is a disaster? In Handbook of Disaster Research; Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E., Dynes, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Quarantelli, E.L. A social science research agenda for the disasters of the 21st century: Theoretical, methodological and empirical issues and their professional implementation. In What Is a Disaster; Quarantelli, E.L., Perry, R.W., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; Volume 325, p. 396. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, R.W.; Quarantelli, E.L. What Is a Disaster? New Answers to Old Questions; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A. Disaster research and future crises: Broadening the research agenda. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 2005, 23, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dé, L.; Rey, T.; Leone, F.; Gilbert, D. Sustainable livelihoods and effectiveness of disaster responses: A case study of tropical cyclone Pam in Vanuatu. Nat. Hazards 2018, 91, 1203–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J.-C. Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. J. Int. Dev. J. Dev. Stud. Assoc. 2010, 22, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K. Disaster studies. Curr. Sociol. 2013, 61, 797–825. [Google Scholar]

- Berke, P.; Beatley, T. After the Hurricane: Linking Recovery to Sustainable Development in the Caribbean; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.P.; Wenger, D. Sustainable disaster recovery: Operationalizing an existing agenda. In Handbook of Disaster Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 234–257. [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky, R.B.; Hopkins, L.D.; Johnson, L.A. Disaster and recovery: Processes compressed in time. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2012, 13, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Wang, L.; Wei, J. The correlations between livelihood capitals and perceived recovery. Disaster Prev. Manag. Int. J. 2020, 30, 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.S.S.; Lin, W.C. Rebuilding relocated tribal communities better via culture: Livelihood and social resilience for disaster risk reduction. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesch, D.J.; Arendt, L.A.; Holly, J.N. Managing for Long-Term Community Recovery in the Aftermath of Disaster; Public Entity Risk Institute: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I. An overview of post-disaster permanent housing reconstruction in developing countries. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2011, 2, 148–164. [Google Scholar]

- Régnier, P.; Neri, B.; Scuteri, S.; Miniati, S. From emergency relief to livelihood recovery: Lessons learned from post-tsunami experiences in Indonesia and India. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2008, 17, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Rose, A.Z. Towards a theory of economic recovery from disasters. Int. J. Mass Emergencies Disasters 2012, 30, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Lewis, D.; Wrathall, D.; Bronen, R.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Huq, S.; Lawless, C.; Nawrotzki, R.; Prasad, V.; Rahman, M.A.; et al. Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C.; Gardoni, P. The Role of Society in Engineering Risk Analysis: A Capabilities-Based Approach. Risk Anal. 2006, 26, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Daly, P.; Mahdi, S.; McCaughey, J.; Mundzir, I.; Halim, A.; Nizamuddin; Ardiansyah; Srimulyani, E. Rethinking relief, reconstruction and development: Evaluating the effectiveness and sustainability of post-disaster livelihood aid. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101650. [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia, K. Sri Lankan livelihoods after the tsunami: Searching for entrepreneurs, unveiling relations of power. Disasters 2015, 39, 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; North Holland Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Long, N. Family and Work in Rural Societies: Perspectives on Non-Wage Labour; Tavistock: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan, L. Livelihoods in development. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. Can. D’étud. Dév. 2017, 38, 22–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington, A. Capitals and Capabilities: A Framework for Analyzing Peasant Viability, Rural Livelihoods and Poverty. World Dev. 1999, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar]

- Dijk, T.v. Livelihoods, capitals and livelihood trajectories:a more sociological conceptualisation. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sakdapolrak, P. Livelihoods as social practices–re-energising livelihoods research with Bourdieu’s theory of practice. Geogr. Helv. 2014, 69, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, G. Staying Secure, Staying Poor: The “Faustian Bargain”. World Dev. 2003, 31, 455–471. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, B.; Lapavitsas, C. Social Capital And Capitalist Economies. South East. Eur. J. Econ. 2004, 2, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, N.; Newsham, A.; Rigg, J.; Suhardiman, D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105898. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar]

- Arlikatti, S.; Andrew, S.A. Housing design and long-term recovery processes in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian ocean tsunami. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2012, 13, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Leon, E.; Kelman, I.; Kennedy, J.; Ashmore, J. Capacity building lessons from a decade of transitional settlement and shelter. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2009, 13, 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, R.; Alexander, B.; Chan-Halbrendt, C.; Salim, W. Sustainable livelihood considerations for disaster risk management: Implications for implementation of the Government of Indonesia tsunami recovery plan. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2006, 15, 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z. From Vulnerability to Resilience: Long-Term Livelihood Recovery in Rural China After the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, P.; Halim, A.; Nizamuddin; Ardiansyah; Hundlani, D.; Ho, E.; Mahdi, S. Rehabilitating coastal agriculture and aquaculture after inundation events: Spatial analysis of livelihood recovery in post-tsunami Aceh, Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 142, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.; Mitchell, J.T.; Cutter, S.L. Evaluating post-Katrina recovery in Mississippi using repeat photography. Disasters 2011, 35, 488–509. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, R.O.; Okazaki, K. Household Livelihood Recovery after 2015 Nepal Earthquake in Informal Economy: Case Study of Shop Owners in Bungamati. Procedia Eng. 2018, 212, 543–550. [Google Scholar]

- Munas, M.; Lokuge, G. Shocks and coping strategies of coastal communities in war–conflict-affected areas of the north and east of Sri Lanka. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2014, 16, 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Mabuku, M.P.; Senzanje, A.; Mudhara, M.; Jewitt, G.; Mulwafu, W. Rural households’ flood preparedness and social determinants in Mwandi district of Zambia and Eastern Zambezi Region of Namibia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 28, 284–297. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.R.; Gordon, A.; Meadows, K.; Zwick, K. Livelihood diversification in Uganda: Patterns and determinants of change across two rural districts. Food Policy 2001, 26, 421–435. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, M. Household income strategies and natural disasters: Dynamic livelihoods in rural Nicaragua. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 592–602. [Google Scholar]

- Patnaik, U.; Narayanan, K. Are traditional coping mechanisms effective in managing the risk against extreme events? Evidences from flood-prone region in rural India. Water Policy 2015, 17, 724–741. [Google Scholar]

- Aitsi-Selmi, A.; Murray, V. Protecting the health and well-being of populations from disasters: Health and health care in the Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2015, 31, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard, J.-C.; Maceda, E.A.; Stasiak, E.; Le Berre, I.; Espaldon, M.V.O. Sustainable livelihoods and people’s vulnerability in the face of coastal hazards. J. Coast. Conserv. 2009, 13, 119–129. [Google Scholar]

- de Mel, S.; McKenzie, D.; Woodruff, C. Mental health recovery and economic recovery after the tsunami: High-frequency longitudinal evidence from Sri Lankan small business owners. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 582–595. [Google Scholar]

- Minamoto, Y. Social capital and livelihood recovery: Post-tsunami Sri Lanka as a case. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2010, 19, 548–564. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, P. The tsunami of 2004 in Sri Lanka: An introduction to impacts and policy in the shadow of civil war. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2009, 63, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, D.A.; Yamao, M. Effects of the tsunami on fisheries and coastal livelihood: A case study of tsunami-ravaged southern Sri Lanka. Disasters 2007, 31, 386–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, J.; Rudolph, P.M. The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2006, 14, 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, T.; Twigg, J.; Rowell, J. Social Vulnerability, Sustainable Livelihoods and Disasters; Conflict and Humanitarian Assistance Department and Sustainable Livelihoods Support Office, Department for International Development: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Arlikatti, S.; Peacock, W.G.; Prater, C.S.; Grover, H.; Sekar, A.S.G. Assessing the impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami on households: A modified domestic assets index approach. Disasters 2010, 34, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. Building Resilience: Integrating Climate and Disaster Risk into Development—The World Bank Group Experience; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thorburn, C. Livelihood recovery in the wake of the tsunami in Aceh. Bull. Indones. Econ. Stud. 2009, 45, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; van der Geest, K.; Ahmed, I.; Huq, S.; Warner, K. A people-centred perspective on climate change, environmental stress, and livelihood resilience in Bangladesh. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS Working Paper No. 72; Institute of Development Studies: Sussex, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. Responsible well-being—A personal agenda for development. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1743–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, M.B.; Riederer, A.M.; Foster, S.O. The Livelihood Vulnerability Index: A pragmatic approach to assessing risks from climate variability and change—A case study in Mozambique. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.U.; Dulal, H.B. Household capacity to adapt to climate change and implications for food security in Trinidad and Tobago. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garai, J. Gender specific vulnerability in climate change and possible sustainable livelihoods of coastal people: A case from Bangladesh. J. Integr. Coast. Zone Manag. 2016, 16, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Xie, L.Z.; Ge, Q.; Pan, Y.X.; Cheung, M. Reconnaissance report on buildings damaged during the Lushan earthquake, April 20, 2013. Nat. Hazards 2015, 76, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, G.; Yu, G.; Cheng, J.; Tan, X.; Zhu, A.; Wen, X. Seismogenic structure of Lushan earthquake and its relationship with Wenchuan earthquake. Front. Earth Sci. 2013, 20, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, Y. Post-Disaster Community Reconstruction Study of Lushan County in Sichuan Province from Governance Horizon. Master’s Thesis, Central China Normal University, Wuhan, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sichuan Statistical Bureau. Sichuan Statistical Yearbook. Sichuan, China; China Statistical Press: Beijing, China, 2013. Available online: https://tjj.sc.gov.cn/scstjj/tjnjnew/pdf/2013.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2018).

- Kachali, H.; Stevenson, J.; Whitman, Z.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Wilson, T. Preliminary Results from Organisational Resilience and Recovery Study. 2011. Available online: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/5c21e9f8-d52b-46aa-908b-779f47dc89f6/content (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Lyttelton Port Company. Lyttelton Port Recovery Plan Information Package. 2014. Available online: http://www.lpc.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Summary-document-LPC-information-package.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Cretney, R.M.; Cretney, R.M. Local responses to disaster: The value of community led post disaster response action in a resilience framework. Disaster Prev. Manag. 2016, 25, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisheries New Zealand. Kaikōura Fisheries 2 Years on from Earthquakes. 2018. Available online: https://www.mpi.govt.nz/news-and-resources/media-releases/kaikoura-fisheries-two-years-on/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Kaikōura District Council. Reimagine Kaikoura Pōhewatia anō a Kaikōura. 2017. Available online: https://www.kaikoura.co.nz/assets/Tourism-Operators/Reimagine-Kaikoura-Kaikoura-Recovery-Plan-WEB.PDF (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Stevenson, J.R.; Becker, J.; Cradock-Henry, N.; Johal, S.; Johnston, D.; Orchiston, C.; Seville, E. Economic and social reconnaissance: Kaikōura earthquake 2016. Bull. N. Z. Soc. Earthq. Eng. 2017, 50, 346–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin, C.C. The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R.; Seville, E. Resourcing challenges for post-disaster housing reconstruction: A comparative analysis. Build. Res. Inf. 2010, 38, 247–264. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji, A. Negotiating Housing Recovery: Why Some Communities Recovered While Others Struggled to Rebuild in Post-Earthquake Urban Kutch, India; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kashem, S.B. Housing practices and livelihood challenges in the hazard-prone contested spaces of rural Bangladesh. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2019, 10, 420–434. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. Building Back Better: The Large-Scale Impact of Small-Scale Approaches to Reconstruction. World Dev. 2009, 37, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, P.K. Allocation of post-disaster reconstruction financing to housing. Build. Res. Inf. 2004, 32, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining the impacts of disaster resettlement from a livelihood perspective: A case study of Qinling Mountains, China. Disasters 2017, 42, 251–274. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Q.; Liu, H.; Feldman, M. Assessing livelihood reconstruction in resettlement program for disaster prevention at Baihe county of China: Extension of the impoverishment risks and reconstruction (IRR) model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchiston, C.; Higham, J. Knowledge management and tourism recovery (de) marketing: The Christchurch earthquakes 2010–2011. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Waimakariri District Council. Waimakariri District 2010 Business Survey: Kaiapoi. 2010. Available online: https://www.waimakariri.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0012/10632/Woodend-Town-Centre-Business-Survey-2010.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Xu, J.; Xu, D.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Q. A bridged government–NGOs relationship in post-earthquake reconstruction: The Ya’an service center in Lushan earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2018, 90, 537–562. [Google Scholar]

- Marincioni, F. Information technologies and the sharing of disaster knowledge: The critical role of professional culture. Disasters 2007, 31, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Haan, L.; Zoomers, A. Exploring the frontier of livelihoods research. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, T.C.; Wall, G. Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, C.-W.; Wei, J.; Wang, Y. Social Capital and Disaster Recovery: Evidence from Sichuan Earthquake in 2008; Center for Global Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Han, Y. Pre-disaster social capital and disaster recovery in Wenchuan earthquake-stricken rural communities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L.J. An invitation to Reflexive Sociology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward, B.M. Rethinking resilience: Reflections on the earthquakes in Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010 and 2011. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, K.; Cao, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D.; Liu, S. Disaster-risk communication, perceptions and relocation decisions of rural residents in a multi-disaster environment: Evidence from Sichuan, China. Habitat Int. 2022, 127, 102646. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Liu, E.; Wang, X.; Tang, H.; Liu, S. Rural Households’ Livelihood Capital, Risk Perception, and Willingness to Purchase Earthquake Disaster Insurance: Evidence from Southwestern China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, G.; Chang-Richards, A.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. What makes a successful livelihood recovery? A study of China’s Lushan earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2020, 105, 2543–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APEC. Building Natural Disaster Response Capacity: Sound Workforce Strategies for Recovery and Reconstruction in APEC Economies. 2013. Available online: https://www.apec.org/publications/2014/02/building-natural-disaster-response-capacity-sound-workforce-strategies-for-recovery-and-reconstruct (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Mamula-Seadon, L.; Selway, K.; Paton, D. Exploring resilience: Learning from Christchurch communities. Tephra 2012, 23, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- NZRC. Evaluation of the Canterbury Earthquake Appeal and Recovery Programme. 2017. Available online: https://alnap.org/help-library/resources/evaluation-of-the-canterbury-earthquake-appeal-and-recovery-programme/ (accessed on 18 April 2020).

- Brown, C.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J. Efficacy of insurance for organisational disaster recovery: Case study of the 2010 and 2011 Canterbury earthquakes. Disasters 2017, 41, 388–408. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Yao, P.; Jiang, S.-j. Perception of earthquake risk: A study of the earthquake insurance pilot area in China. Nat. Hazards 2014, 74, 1595–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, D.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Potangaroa, R. A conceptual framework for measuring livelihood resilience: Relocation experience from Aceh, Indonesia. World Dev. 2019, 117, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.P.; Zhu, F.B.; Qiu, X.P.; Zhao, S. Effects of natural disasters on livelihood resilience of rural residents in Sichuan. Habitat Int. 2018, 76, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Y. Analysis of farmers’ satisfaction towards concentrated rural settlement development after the Wenchuan earthquake. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Spector, S.; Orchiston, C.; Chowdhury, M. Psychological resilience, organizational resilience and life satisfaction in tourism firms: Insights from the Canterbury earthquakes. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1216–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D. Which is a better predictor of job performance: Job satisfaction or life satisfaction? J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2006, 8, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, L.; Shinfuku, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C.; Shen, Y. Longitudinal study of earthquake-related PTSD in a randomly selected community sample in north China. Am. J. Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, M. One year later: Mental health problems among survivors in hard-hit areas of the Wenchuan earthquake. Public Health 2011, 125, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Jiang, X.; Yao, J.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Pang, M.; Chiang, C.L.V. Depression, social support, and coping styles among pregnant women after the lushan earthquake in ya’an, China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Tian, J.; Zhu, X.; Miao, D. Self-efficacy, social support, and coping strategies of adolescent earthquake survivors in China. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2010, 38, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, K.I.; Moser, K. Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 264–282. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Qing, C.; Deng, X.; Yong, Z.; Zhou, W.; Ma, Z. Disaster risk perception, sense of pace, evacuation willingness, and relocation willingness of rural households in earthquake-stricken areas: Evidence from Sichuan Province, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CERA. Canterbury Wellbeing Index; PUB145.1306; Canterbury Earthquake Recovery Authority: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spittlehouse, J.K.; Joyce, P.R.; Vierck, E.; Schluter, P.J.; Pearson, J.F. Ongoing adverse mental health impact of the earthquake sequence in Christchurch, New Zealand. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Park, A.; Wang, S. Migration and rural poverty in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2005, 33, 688–709. [Google Scholar]

- Orchiston, C. Tourism business preparedness, resilience and disaster planning in a region of high seismic risk: The case of the Southern Alps, New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 477–494. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, L.; Wang, L.; Li, S. Lushan’s New Road: Innovation and Practice in the Local Initiative Responsibility System and Mechanism on the Recovery and Reconstruction After 4.20 Lushan Earthquake; Sichuan University: Chengdu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Comerio, M.C. Housing Recovery in Chile: A Qualitative Mid-Program Review; PEER Report; Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Component | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Housing/Sheltering | Housing condition | [12,65] |

| Safety and robustness of a house | [65,66] | |

| Employment | Income resources | [67,68,69,70,71] |

| Education and skills | [72,73,74,75,76] | |

| Personal well-being | Physical health | [67,77,78] |

| Mental health | [67,79] | |

| External assistance | Social networks | [80] |

| Government policies | [81,82,83] |

| Time | Location | Number of Interviewees | Interviewee Code | Location | Occupations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 July | Lushan County | 5 | B1–B5 | Baihuo | 2 migrant workers, 3 farmers |

| 5 | W1–W5 | Wanghuo | 2 migrant workers, 2 farmers, 1 self-employed | ||

| 5 | WN1–WN5 | Zhanghuo | 2 migrant workers, 2 farmers, 1 self-employed | ||

| 5 | Z1–Z5 | Fujiaying | 2 migrant workers, 1 farmer, 2 self-employed | ||

| 18 June | Christchurch and Kaikōura | 6 | KP1-KP6 | Kaiapoi | 3 employees, 2 shop owners, 1 work in real estate |

| 3 | L1-L3 | Lyttelton | 2 employees, 1 shop owner | ||

| 14 | K1-K14 | Kaikōura | 7 employees, 6 shop owners, 1 work in real estate |

| Category | Component | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | Income resources | [67,68,69,70,71] |

| Education and skills | [72,73,74,75,76] | |

| Access to employment opportunities | Pilot study | |

| Need for work–life balance | Pilot study | |

| Housing/Shelter | Housing conditions | [12,65] |

| Safety and robustness of a house | [65,66] | |

| Housing functionality | Pilot study | |

| Housing ownership | Pilot study | |

| External assistance | Social networks | [80] |

| Government policies | [81,82,83] | |

| Assistance from extended families | Pilot study | |

| NGOs’ assistance | Pilot study | |

| Personal well-being | Physical health | [67,77,78] |

| Mental health | [67,79] | |

| Quality of life | Pilot study | |

| Livelihood satisfaction | Pilot study | |

| Sense of security | Pilot study |

| Lushan, China | Christchurch and Kaikōura, New Zealand | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ranking Within the Category | Overall Ranking | Ranking Within the Category | Overall Ranking | ||

| Housing | Housing functionality | 1 | 3 | 3 | 16 |

| Housing condition | 2 | 4 | 2 | 11 | |

| Safety and robustness of a house | 3 | 9 | 1 | 9 | |

| Housing ownership | 4 | 15 | 3 | 17 | |

| Employment | Income resources | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Access to employment opportunities | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | |

| Education and skills | 3 | 8 | 4 | 15 | |

| Work–life balance | 4 | 17 | 3 | 14 | |

| Personal well-being | Quality of life | 1 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| Livelihood satisfaction | 2 | 10 | 5 | 18 | |

| Physical health | 3 | 11 | 3 | 8 | |

| Mental health | 4 | 13 | 1 | 6 | |

| Feeling of security | 5 | 16 | 2 | 7 | |

| External assistance | Assistance from external families | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| Social networks | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | |

| Government’s assistance | 3 | 12 | 2 | 5 | |

| NGOs’ assistance | 4 | 14 | 4 | 13 | |

| Other components | Insurance policies | 1 | 1 | ||

| Insurance Type | Interviewees | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Business interruption insurance | KP2, K1, K9, k14 | The insurnace covered the expenditures for 12 weeks with NZD 400–500 each week (K1). |

| Content insurance/replacement insurance (EQC) | KP5, KP6, L2, K3, K12 | Everything related to insurance needs to be well documented (KP6); it was hard to claim the insurance, NZD 5000–6000 (L2). |

| Employment insurance | L3 | Individual insurance covered NZD 500 for 6 weeks (L39). |

| Life and sickness insurance | L3, K5 | The paperwork took lots of time. |

| Components in Both Countries | Components in China not in New Zealand | Components in New Zealand not in China | Non-Critical Components in Both Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income resources | Assistance from external families | Insurance policies | Housing ownership |

| Access to employment opportunities | Housing functionality | Government’s assistance | Work–life balance |

| Social networks | Housing condition | Mental health | Livelihood satisfaction |

| Safety and robustness of a house | Education and skills | Feeling of security | NGOs’ assistance |

| Quality of life | Physical health |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pu, G. What Constitutes a Successful Livelihood Recovery: A Comparative Analysis Between China and New Zealand. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073186

Pu G. What Constitutes a Successful Livelihood Recovery: A Comparative Analysis Between China and New Zealand. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073186

Chicago/Turabian StylePu, Gujun. 2025. "What Constitutes a Successful Livelihood Recovery: A Comparative Analysis Between China and New Zealand" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073186

APA StylePu, G. (2025). What Constitutes a Successful Livelihood Recovery: A Comparative Analysis Between China and New Zealand. Sustainability, 17(7), 3186. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073186