Sustaining Competitiveness and Profitability Under Asymmetric Dependence: Supplier–Buyer Relationships in the Korean Automotive Industry

Abstract

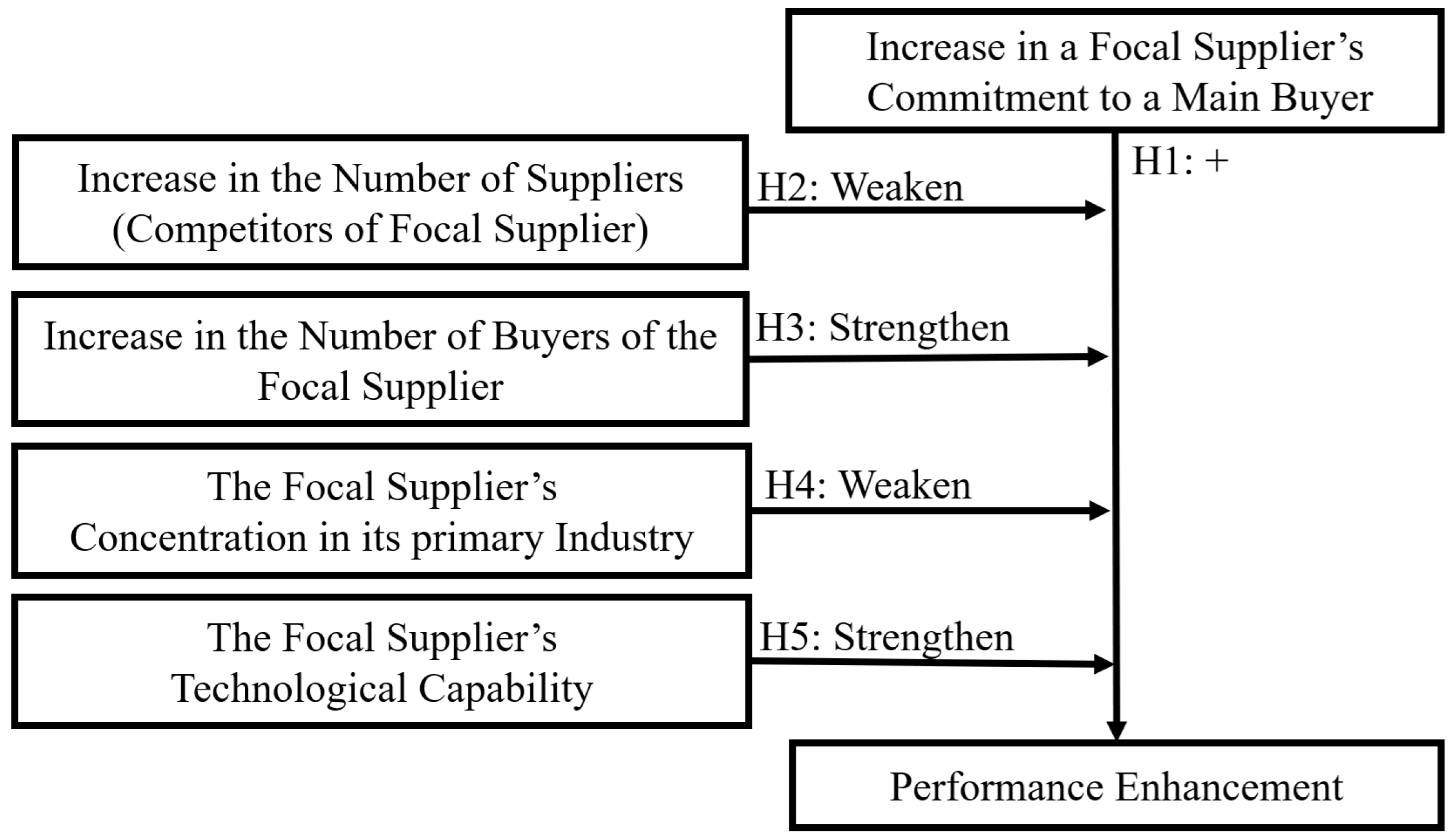

1. Introduction

Asymmetric Dependence

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Asymmetric Dependence Between Transaction Partners

2.2. Commitment to an Exchange Partner

2.3. New Exchange Relationships

2.4. Diversification and Concentration

2.5. Technological Capability

3. Methodology

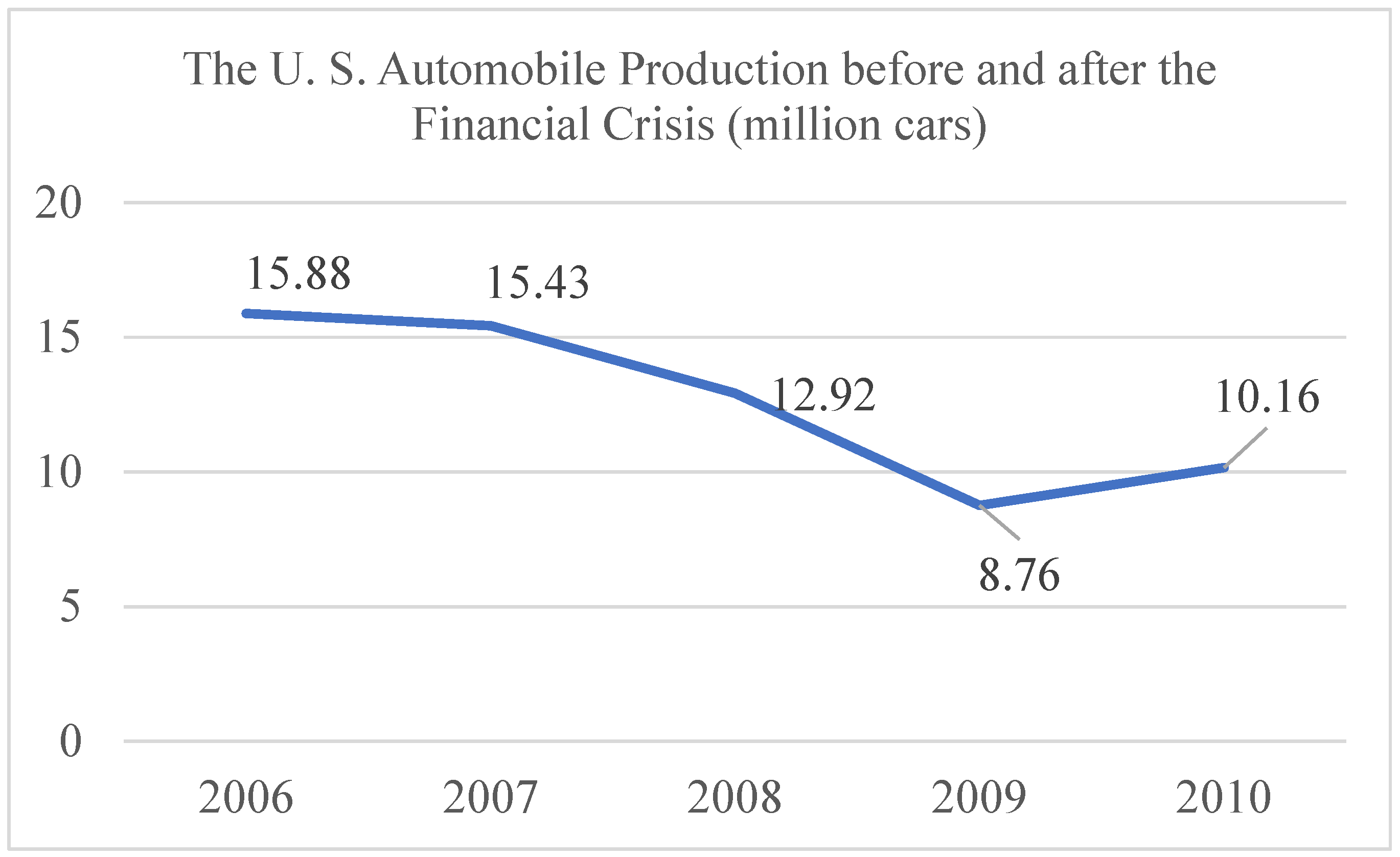

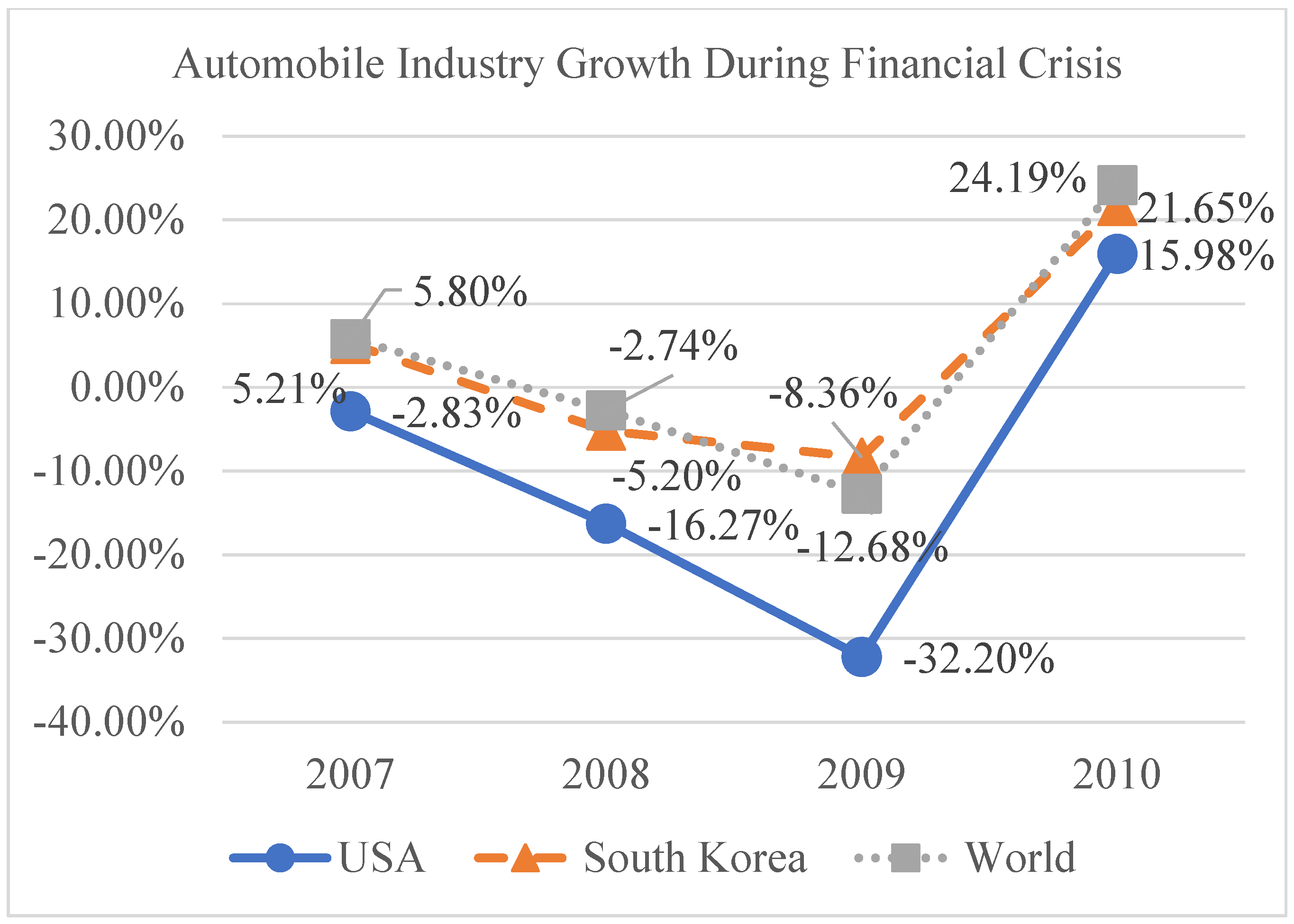

3.1. Korean Automobile Industry

3.2. Data and Sample

3.3. Dependent Variable

3.4. Independent Variable and Moderating Variables

3.5. Control Variables

3.6. Empirical Model

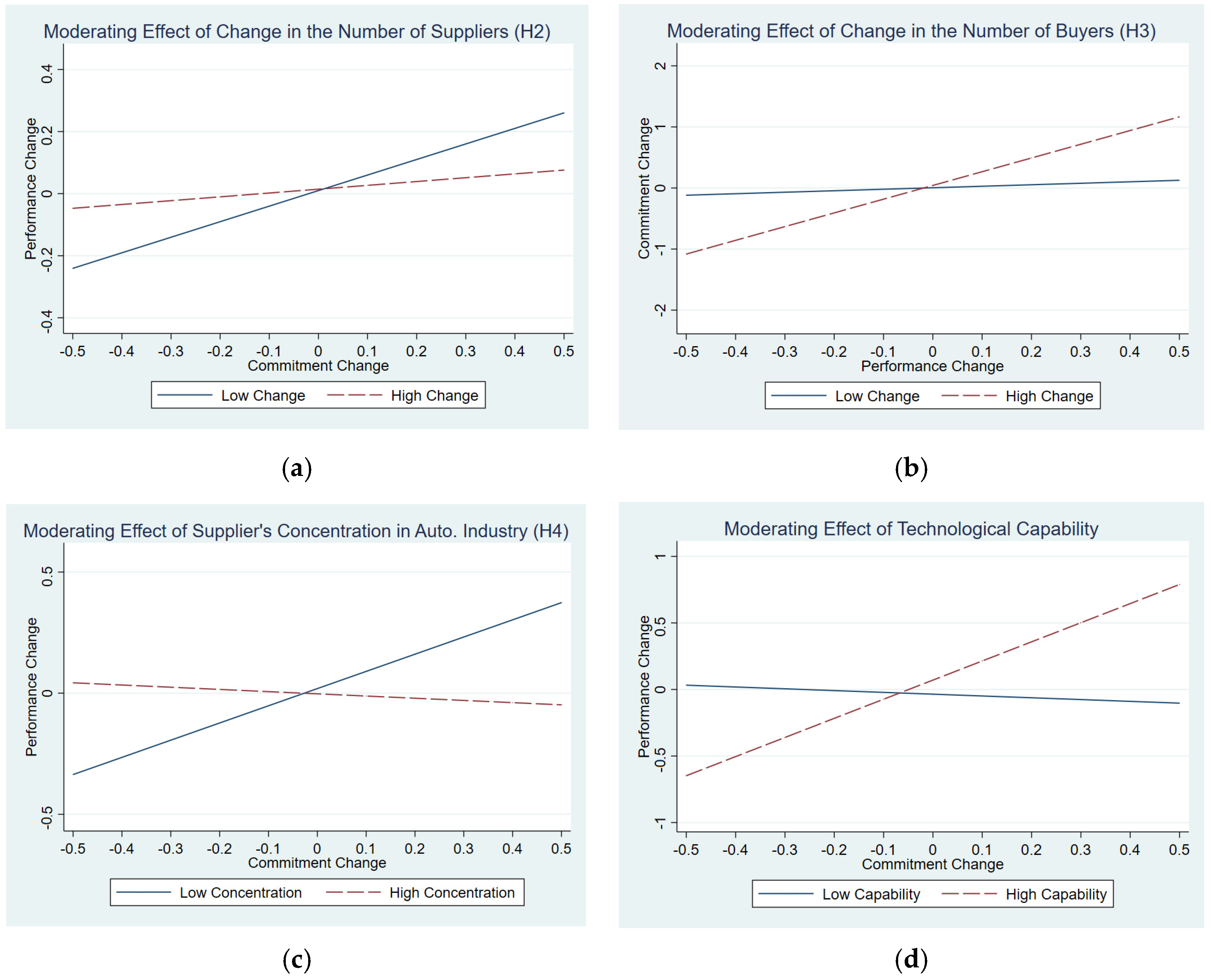

4. Results

4.1. Main Analysis

4.2. Robustness Check

5. Discussion

5.1. Contributions

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KAICA | Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association |

| FLGS | Feasible generalized least squares |

| ROA | Return on asset |

References

- Porter, M.E. The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Originally published by Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith, C.S.; Stiles, C.H. Merger strategies as a response to bilateral market power. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, T.; Piskorski, M.J. Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Adm. Sci. Q. 2005, 50, 167–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Yeung, A.C.L.; Han, Z.; Huo, B. The Effect of Customer and Supplier Concentrations on Firm Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Resource Dependence and Power Balancing. J. Oper. Manag. 2023, 69, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurakhmonov, M.; Ridge, J.W.; Hill, A.D. Unpacking Firm External Dependence: How Government Contract Dependence Affects Firm Investments and Market Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 64, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, R.; Sytch, M. Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on a manufacturer’s performance in procurement relationships. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 32–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, T.Y. Tie Strength and Value Creation in the Buyer–Supplier Context: A U-Shaped Relation Moderated by Dependence Asymmetry. J. Manag. 2015, 41, 1954–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Choe, C. When Does Auto-Parts Suppliers’ Innovation Reduce Their Dependence on the Automobile Assembler? J. Korea Trade 2020, 24, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Fortado, B. Outcomes of supply chain dependence asymmetry: A systematic review of the statistical evidence. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 5844–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Mun, H.J.; Park, K.M. When is dependence on other organizations burdensome? The effect of asymmetric dependence on internet firm failure. Strat. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 2058–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallen, B.L.; Katila, R.; Rosenberger, J.D. How do social defenses work? A resource-dependence lens on technology ventures, venture capital investors, and corporate relationships. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1078–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Shanley, M. Industry determinants of the “merger versus alliance” decision. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, C. Organizational Analysis: A Sociological View; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Subramani, M.R.; Venkatraman, N. Safeguarding investments in asymmetric interorganizational relationships: Theory and evidence. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Weber, D. A transaction cost approach to make-or-buy decisions. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artz, K.W. Buyer–supplier performance: The role of asset specificity, reciprocal investments and relational exchange. Br. J. Manag. 1999, 10, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, M.; Greve, H.R. Resource dependence dynamics: Partner reactions to mergers. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lewis, M. Trust and Distrust in Buyer–Supplier Relationships: An Exploratory Study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 44, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzi, D.; Matopoulos, A.; Clegg, B. Managing Resource Dependencies in Electric Vehicle Supply Chains: A Multi-Tier Case Study. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M.; Coley, L.S.; Lindemann, E. Financially distressed suppliers: Exit, neglect, voice or loyalty? Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 33, 1500–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Chu, W. The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R. Goodwill and the spirit of market capitalism. Br. J. Sociol. 1983, 34, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Sirgy, M.J.; Bird, M.M. Reducing buyer decision-making uncertainty in organizational purchasing: Can supplier trust, commitment, and dependence help? J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, I.W.G.; Suh, T. Factors affecting the level of trust and commitment in supply chain relationships. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 40, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, A.; McEvily, B.; Perrone, V. Does trust matter? Exploring the effects of interorganizational and interpersonal trust on performance. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H. Specialized supplier networks as a source of competitive advantage: Evidence from the auto industry. Strat. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, J.H.; Chu, W. The determinants of trust in supplier-automaker relationships in the U.S., Japan, and Korea. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2000, 31, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, G.T.; Cadotte, E.R. Exchange interdependence and interfirm interaction: Research in a simulated channel setting. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoetker, G.; Swaminathan, A.; Mitchell, W. Modularity and the impact of buyer–supplier relationships on the survival of suppliers. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y. Financial distress and customer-supplier relationships. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 43, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDuffie, J.P.; Helper, S. Creating lean suppliers: Diffusing lean production through the supply chain. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 39, 118–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizruchi, M.S. Similarity of political behavior among large American corporations. Am. J. Sociol. 1989, 95, 401–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provan, K.G.; Gassenheimer, J.B. Supplier commitment in relational contract exchanges with buyers: A study of interorganizational dependence and exercised power. J. Manag. Stud. 1994, 31, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, J.Y.; Brynjolfsson, E. Information technology, incentives, and the optimal number of suppliers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1993, 10, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.M.; Friedl, G. Supplier switching decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 183, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molm, L.D.; Takahashi, N.; Peterson, G. Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. Am. J. Sociol. 2000, 105, 1396–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.F.; Cobb, J.A. Resource dependence theory: Past and future. In Stanford’s Organization Theory Renaissance, 1970–2000; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khieng, S.; Dahles, H. Resource dependence and effects of funding diversification strategies among NGOs in Cambodia. Voluntas 2015, 26, 1412–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gord, M. Diversification and Integration in American Industry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, M. Subcontracting relations in the Korean automotive industry: Risk sharing and technological capability. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 1999, 17, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Sastry, T. Automotive industry in emerging economies: A comparison of South Korea, Brazil, China and India. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 1996, 31, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, L. Crisis construction and organizational learning: Capability building in catching-up at Hyundai Motor. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, D.; Choi, C.J.; Choi, E. The globalization strategy of Daewoo Motor Company. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 1998, 15, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2019 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.; Rhee, H. Effects of FTA provisions on the market structure of the Korean automobile industry. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2014, 45, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, C. Supply Chain Efficiency Measurement to Maintain Sustainable Performance in the Automobile Industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 1997 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 1998 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 1999 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2000 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2001 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2002 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2003 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2004 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2005 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2006 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association. 2007 Yearbook of Automobile Industry; Korea Auto Industries Cooperation Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Benmelech, E.; Meisenzahl, R.R.; Ramcharan, R. The real effects of liquidity during the financial crisis: Evidence from automobiles. Q. J. Econ. 2017, 132, 317–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.J.; Maine, E. Market entry strategies for electric vehicle start-ups in the automotive industry: Lessons from Tesla Motors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, J.M.; Heugens, P.P. Synthesizing and extending resource dependence theory: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Zona, F.; Gomez-Mejia, L.R.; Withers, M.C. Board interlocks and firm performance: Toward a combined agency–resource dependence perspective. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 589–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Young, C.E.; Morris, J.R. Financial consequences of employment-change decisions in major US corporations. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 1175–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jifri, A.O.; Drnevich, P.; Jackson, W.; Dulek, R. Examining the Sustainability of Contributions of Competing Core Organizational Capabilities in Response to Systemic Economic Crises. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D. Dependency and vulnerability: An exchange approach to the control of organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1974, 19, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemin, A.P.; Berry, C.H. Entropy measure of diversification and corporate growth. J. Ind. Econ. 1979, 27, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Al-Shammari, H.A.; Kim, B.; Lee, S.H. CEO duality leadership and corporate diversification behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 1173–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palepu, K. Diversification strategy, profit performance and the entropy measure. Strat. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, A.M.; Bryce, D.J.; Posen, H.E. On the strategic accumulation of intangible assets. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Makhija, M. Flexibility in internationalization: Is it valuable during an economic crisis? Strat. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Makhija, M. The effect of domestic uncertainty on the real options value of international investments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganda, F. Investigating the Relationship and Impact of Environmental Governance, Green Goods, Non-Green Goods and Eco-Innovation on Material Footprint and Renewable Energy in the BRICS Group. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Beamish, P.W.; Lee, H.-U.; Park, J.H. Strategic choice during economic crisis: Domestic market position, organizational capabilities and export flexibility. J. World Bus. 2009, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteverde, K.; Teece, D.J. Supplier switching costs and vertical integration in the automobile industry. Bell J. Econ. 1982, 13, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, B. Research note: An analysis of specificity in transaction cost economics. Organ. Stud. 1993, 14, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Solutions Suggested | Dynamic Variable Used | Focus | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hillman et al. (2009) [7] | Merger and Acquisition | N/A | N/A | Review paper; conventional solutions in resource dependence theory |

| Organizational relationships including joint ventures | ||||

| Board Interlocks | ||||

| Political action | ||||

| Executive succession | ||||

| Chen and Lewis (2024) [22] | Relational norms, trust | No | Supplier | Automotive industry |

| Kang and Choe (2020) [12] | Geographical diversification, global knowledge sourcing | No | Supplier | Automotive industry |

| Gulati and Sytch (2007) [10] | Joint dependence, relational embeddedness | No | Both buyer and supplier | Automotive industry |

| Kim and Choi (2015) [11] | Strength of ties, resource complementarity | No | Both buyer and supplier | Automotive industry |

| Kalaitzi et al. (2019) [23] | Long-term relationship | No | Buyer | Automotive industry; electric car manufacturer |

| Wagner et al. (2021) [24] | Cooperation | No | Buyer | Automotive Industry; measured buyer’s dependence on supplier |

| Variables | Obs. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Change in ROA | 193 | 0.00 | 0.18 | −1.25 | 1.71 |

| (2) Age (log) | 193 | 3.41 | 0.37 | 1.95 | 4.13 |

| (3) Size (asset log) | 193 | 11.42 | 0.98 | 7.84 | 14.46 |

| (4) Growth (asset growth) | 193 | 0.10 | 0.22 | −0.40 | 1.97 |

| (5) Debt Ratio | 193 | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 2.35 |

| (6) Quality Flag | 193 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (7) Export Flag | 193 | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| (8) Main Product Weight | 193 | 0.57 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 1.00 |

| (9) Primary Buyer Dependency | 193 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.99 |

| (10) Change in Commitment | 193 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.45 | 0.16 |

| (11) Change in the Number of Suppliers (%) | 193 | 0.15 | 0.63 | −0.83 | 5.00 |

| (12) Change in the Number of Buyers (%) | 193 | −0.01 | 0.25 | −0.67 | 1.00 |

| (13) Supplier’s Concentration on Auto. Industry | 193 | 0.90 | 0.16 | 0.39 | 1.00 |

| (14) Technological Capability (%) | 193 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| (1) Change in ROA | 1.00 | ||||||

| (2) Age (log) | −0.04 | 1.00 | |||||

| (3) Size (asset log) | −0.02 | 0.41 *** | 1.00 | ||||

| (4) Growth (asset growth) | 0.12 | −0.19 ** | −0.02 | 1.00 | |||

| (5) Debt Ratio | −0.02 | −0.09 | 0.20 ** | −0.10 | 1.00 | ||

| (6) Quality Flag | 0.04 | −0.13 | −0.14 | 0.03 | −0.16 * | 1.00 | |

| (7) Export Flag | −0.02 | 0.37 *** | 0.11 | −0.06 | 0.10 | −0.22 ** | 1.00 |

| (8) Main Product Weight | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.13 † | 0.10 | 0.05 | −0.12 |

| (9) Primary Buyer Dependency | 0.09 | −0.24 *** | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.27 |

| (10) Change in Commitment | 0.21 ** | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.06 |

| (11) Change in the No. of Suppliers (%) | −0.03 | −0.16 * | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.05 |

| (12) Change in the No. of Buyers (%) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.20 ** | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| (13) Supplier’s Concent. on Auto. Ind. | −0.04 | −0.34 *** | −0.41 *** | 0.12 † | −0.33 *** | 0.12 † | −0.20 |

| (14) Technological Capability (%) | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.09 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.12 |

| Variables | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | (14) |

| (8) Main Product Weight | 1.00 | ||||||

| (9) Primary Buyer Dependency | 0.15 * | 1.00 | |||||

| (10) Change in Commitment | −0.08 | 0.12 † | 1.00 | ||||

| (11) Change in the No. of Suppliers (%) | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.00 | |||

| (12) Change in the No. of Buyers (%) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 1.00 | ||

| (13) Supplier’s Concent. on Auto. Ind. | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 1.00 | |

| (14) Technological Capability (%) | −0.06 | −0.14 * | −0.11 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 1.00 |

| DV: Change in ROA | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Dummy | (Included) | ||||||

| Age (log) | 0.0144 | 0.0071 | 0.0062 | −0.0003 | −0.0111 | 0.0086 | −0.0108 |

| (0.0369) | (0.0377) | (0.0362) | (0.0368) | (0.0355) | (0.0379) | (0.0325) | |

| Size (asset log) | 0.0043 | 0.0026 | 0.0009 | 0.0021 | −0.0002 | 0.0035 | 0.0000 |

| (0.0131) | (0.0134) | (0.0129) | (0.0131) | (0.0128) | (0.0137) | (0.0118) | |

| Growth (asset growth) | −0.0043 | −0.0172 | 0.0051 | −0.0286 | 0.0197 | −0.0204 | 0.0180 |

| (0.0699) | (0.0698) | (0.0694) | (0.0689) | (0.0631) | (0.0698) | (0.0611) | |

| Debt Ratio | 0.0042 | −0.0016 | −0.0001 | −0.0348 | −0.1024 * | −0.0110 | −0.1386 ** |

| (0.0512) | (0.0519) | (0.0503) | (0.0532) | (0.0508) | (0.0526) | (0.0491) | |

| Quality Flag | 0.0159 | 0.0255 | 0.0247 | 0.0232 | 0.0323 | 0.0254 | 0.0304 |

| (0.0290) | (0.0293) | (0.0286) | (0.0287) | (0.0265) | (0.0295) | (0.0246) | |

| Export Flag | 0.0093 | 0.0165 | 0.0236 | 0.0140 | 0.0231 | 0.0141 | 0.0266 |

| (0.0286) | (0.0292) | (0.0284) | (0.0284) | (0.0267) | (0.0294) | (0.0249) | |

| Main Product Weight | −0.0109 | 0.0021 | 0.0205 | 0.0160 | 0.0153 | 0.0067 | 0.0489 |

| (0.0472) | (0.0483) | (0.0476) | (0.0478) | (0.0446) | (0.0487) | (0.0417) | |

| Primary Buyer Dependency | 0.0286 | 0.0203 | −0.0007 | 0.0131 | 0.0377 | 0.0267 | 0.0121 |

| (0.0503) | (0.0514) | (0.0505) | (0.0502) | (0.0472) | (0.0521) | (0.0445) | |

| (1) Change in Commitment (H1) | 0.4157 * | 0.5117 ** | 0.5317 *** | 4.5055 *** | 0.3691 * | 5.4106 *** | |

| (0.1636) | (0.1694) | (0.1741) | (0.6000) | (0.1763) | (0.6096) | ||

| (2) Change in the Number of Suppliers (%) | −0.0023 | 0.0138 | |||||

| (0.0262) | (0.0225) | ||||||

| (1) × (2) (H2) | −0.9179 * | −0.9077 † | |||||

| (0.4691) | (0.4772) | ||||||

| (3) Change in the Number of Buyers (%) | 0.0707 | 0.0327 | |||||

| (0.0632) | (0.0541) | ||||||

| (1) × (3) (H3) | 2.0484 * | 2.6767 ** | |||||

| (0.9674) | (0.9941) | ||||||

| (4) Supplier’s Cocent. on Auto. Ind. | −0.2583 *** | −0.2241 ** | |||||

| (0.0779) | (0.0714) | ||||||

| (1) × (4) (H4) | −5.0201 *** | −5.9098 *** | |||||

| (0.7189) | (0.7134) | ||||||

| (5) Technological Capability (%) | 1.0440 | 0.7594 | |||||

| (0.9245) | (0.7711) | ||||||

| (1) × (5) (H5) | 10.2692 | 12.7905 | |||||

| (11.3469) | (9.7559) | ||||||

| Constant | −0.1484 | −0.1127 | −0.0943 | −0.0648 | 0.2467 | −0.1338 | 0.2192 |

| (0.1747) | (0.1783) | (0.1722) | (0.1749) | (0.2226) | (0.1811) | (0.2039) | |

| Observations | 186 | 186 | 186 | 186 | 186 | 186 | 186 |

| Wald X2 | 23.88 | 30.89 | 35.37 | 37.73 | 89.88 | 32.47 | 125.39 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Model | Random Effect | Fixed Effect | FGLS |

| Dependent Variable | Change in ROA | Change in ROA | ROA |

| Year Dummy | (Included) | ||

| Age (log) | −0.0276 | −0.1713 | −0.0642 * |

| (0.0373) | (0.4462) | (0.0301) | |

| Size (asset log) | −0.0036 | 0.0252 | 0.0211 † |

| (0.0133) | (0.0814) | (0.0109) | |

| Growth (asset growth) | 0.0875 | 0.0605 | 0.1067 * |

| (0.0543) | (0.0827) | (0.0435) | |

| Debt Ratio | −0.1651 ** | −0.2816 ** | −0.3729 *** |

| (0.0563) | (0.0929) | (0.0413) | |

| Quality Flag | 0.0343 | 0.0437 | 0.0487 * |

| (0.0276) | (0.0351) | (0.0192) | |

| Export Flag | 0.0317 | 0.0402 | 0.0507 * |

| (0.0287) | (0.0631) | (0.0221) | |

| Main Product Weight | 0.0559 | −0.0257 | 0.0660 † |

| (0.0485) | (0.1908) | (0.0383) | |

| Primary Buyer Dependency | 0.0140 | 0.3597 * | −0.0040 |

| (0.0519) | (0.1562) | (0.0407) | |

| (1) Change in Commitment (H1) | 5.6016 *** | 5.9166 *** | 1.9905 *** |

| (0.6496) | (0.7212) | (0.4098) | |

| (2) Change in the Number of Suppliers (%) | 0.0085 | 0.0118 | 0.0077 |

| (0.0180) | (0.0272) | (0.0148) | |

| (1) × (2) (H2) | −1.2093 * | −1.2833 * | −1.2127 *** |

| (0.5242) | (0.6046) | (0.3442) | |

| (3) Change in the Number of Buyers (%) | 0.0500 | 0.0602 | 0.0285 |

| (0.0482) | (0.0638) | (0.0355) | |

| (1) × (3) (H3) | 1.6464 † | 2.9081 * | −0.4859 |

| (0.9649) | (1.2109) | (0.6925) | |

| (4) Supplier’s Cocent. on Auto. Ind. | −0.2720 ** | −0.5387* | −0.2137 *** |

| (0.0834) | (0.2573) | (0.0641) | |

| (1) × (4) (H4) | −6.1783 *** | −6.6383 *** | −2.2338 *** |

| (0.7680) | (0.8656) | (0.4798) | |

| (5) Technological Capability (%) | 0.7493 | 1.5089 | 0.6553 |

| (0.8973) | (1.5845) | (0.6501) | |

| (1) × (5) (H5) | 13.8344 | 10.4058 | 4.4342 |

| (10.7711) | (12.1716) | (7.0401) | |

| Constant | 0.3613 | 0.6970 | 0.2820 |

| (0.2272) | (1.7645) | (0.1854) | |

| Observations | 193 | 193 | 186 |

| overall R2 | 0.4164 | 0.2742 | |

| within R2 | 0.4356 | 0.4668 | |

| between R2 | 0.4209 | 0.3164 | |

| Wald x2 | 118.44 | 177.14 | |

| F | 4.48 | ||

| Supported Hypotheses | H1, H2, H3, H4 | H1, H2, H3, H4 | H1, H2, H4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, K. Sustaining Competitiveness and Profitability Under Asymmetric Dependence: Supplier–Buyer Relationships in the Korean Automotive Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073089

Kim K. Sustaining Competitiveness and Profitability Under Asymmetric Dependence: Supplier–Buyer Relationships in the Korean Automotive Industry. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073089

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Kyun. 2025. "Sustaining Competitiveness and Profitability Under Asymmetric Dependence: Supplier–Buyer Relationships in the Korean Automotive Industry" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073089

APA StyleKim, K. (2025). Sustaining Competitiveness and Profitability Under Asymmetric Dependence: Supplier–Buyer Relationships in the Korean Automotive Industry. Sustainability, 17(7), 3089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073089