Dynamic Effects of Education Investment on Sustainable Development Based on Comparative Empirical Research Between China and the United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. On Connotations of Sustainable Development

2.2. On the Impact of Education Investment on Sustainable Development

2.3. Summary

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. General Discussion on the Impact Mechanism of Education Investment on Sustainable Development

3.2. Impact Mechanism of Education Investment on Economic Sustainable Development

3.3. Impact Mechanism of Education Investment on Social Sustainable Development

3.4. Impact Mechanism of Education Investment on Ecological Sustainable Development

4. Research Design

4.1. General Design

4.2. Model Construction

4.3. Indicator Selection and Data Sources

5. Empirical Analysis and Results Discussion

5.1. Empirical Analysis

- (1)

- Table 2 reveals the following findings:

- (a)

- Impact of Lagged Chinese Educational Investment

- (b)

- Impact of Lagged American Educational Investment

- (2)

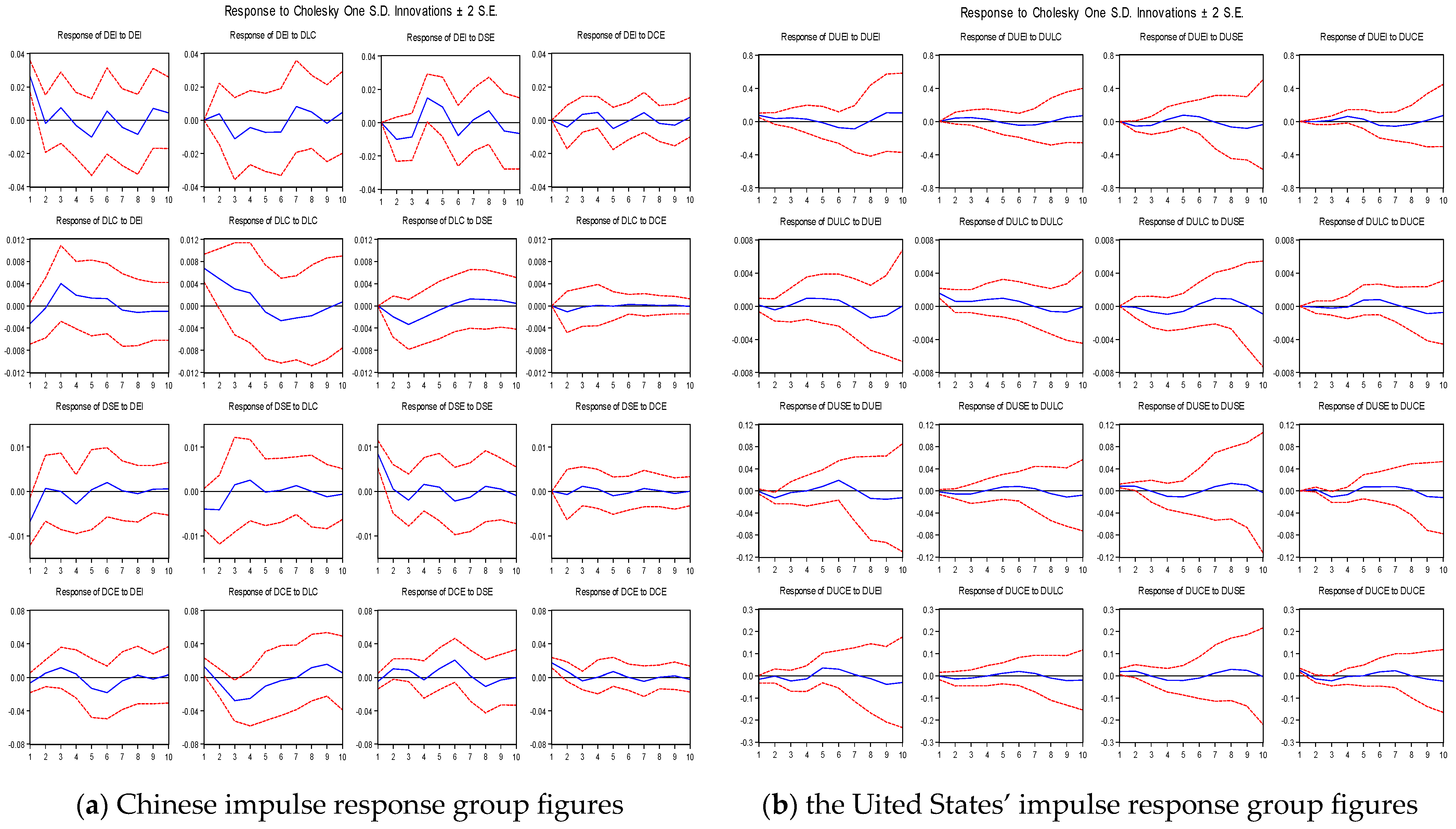

- Figure 2a,b illustrate the following:

5.2. Discussion Between Findings in This Study and Previous Studies

- (1)

- Impact on Economic Sustainable Development

- (2)

- Influence on Social Sustainable Development

- (3)

- Effect on Ecological Sustainable Development

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Research Conclusions

- (a)

- Theoretically, sustainable development is a sophisticated and dynamic process characterized by a three-dimensional connotation structure encompassing economic, social, and ecological dimensions. Education investment, by enhancing educational capacity and delivering high-quality education services, can positively influence human capital accumulation. This, in turn, drives economic sustainable development. It also promotes social justice, which is the cornerstone of social sustainable development, and contributes to carbon emission reduction, facilitating ecological sustainable development.

- (b)

- Empirical studies provide partial support for the theoretical hypothesis. Specifically, the VAR regression results and impulse response curves of China and the United States corroborate the theoretical perspective that the impact of educational investment on sustainable development is a dynamic process. The direction and strength of the effect of educational investment on sustainable development vary over time and depend on the development conditions of different countries. This is consistent with the need for a more comprehensive and dynamic analysis of the relationship between education investment and sustainable development, as previous studies have mainly focused on single- or two-dimensional aspects, and discussions on the dynamic impact are still insufficient.

- (c)

- In the context of China, the previous year’s educational investment can indeed promote current social equality. However, it slightly impedes talent capital accumulation, ecological development, and its own growth. This short-term deviation from the general theoretical expectation may be due to inefficiencies in resource allocation in the short run, as discussed in the comparison with previous studies. For example, new educational facilities may not be fully utilized immediately, or there could be a time lag in training and deploying qualified teachers. The educational investment from the year before last still promotes social equality. Additionally, it can increase per capita schooling years, thereby promoting talent capital accumulation. In terms of coefficients, its negative impact on ecological development is less severe compared to the previous year, and it inhibits the current growth of educational investment to a lesser extent. This shows a declining trend in the strength of its effects, indicating that over time, the positive impacts of education investment on economic and ecological aspects start to emerge, which is in line with the long-term positive relationship between education investment and sustainable development found in previous studies.

6.2. Recommendations

- (1)

- Broaden and Diversify Education Investment Sources

- (2)

- Targeted Allocation of Education Investment

- (3)

- Implement Dynamic Adjustment of Education Investment

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schultz, T.W. Investment in Human Capital. Am. Econ. Rev. 1961, 51, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, G. Investment in Education. Stud. Ir. Q. Rev. 1965, 54, 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/zh/development-agenda/ (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-10/12/content_5550452.htm (accessed on 17 March 2025). (In Chinese)

- China’s Polulation Consus Yearbook 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/zk/indexch.htm (accessed on 16 March 2025). (In Chinese)

- Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, W. Research on the Dynamic Coupling and Coordination of Health Investment, Educational Investment and Economic Development in Western China. Med. Soc. 2023, 36, 55–61. Available online: https://www.chndoi.org/Resolution/Handler?doi=10.13723/j.yxysh.2023.09.010 (accessed on 17 March 2025). (In Chinese).

- Sustainable Cleveland 2019-Action and Resources Guide. Reports. 2019. Available online: https://jstor.org/stable/community.32537557 (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- United Nations Brundtland Commission. 1987. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Duran, D.C.; Gogan, L.M.; Artene, A.; Duran, V. The components of sustainable development—A possible approach. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 26, 806–811. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Ma, X.; Mu, H.; Li, P. The inequality of natural resources consumption and its relationship with the social development level based on the ecological footprint and the HDI. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2010, 12, 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schebesta, H.; Bernaz, N.; Macchi, C.; Zuniga, F.R.; Nsour, M.F.; Ali, A.N.M.A.; Solaiman, S.M. The European Union Farm to Fork Strategy: Sustainability and Responsible Business in the Food Supply Chain. Eur. Food Feed. Law Rev. 2020, 15, 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- Psacharopoulos, G.; Patrinos, H.A. Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Educ. Econ. 2018, 26, 445–458. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Chu, Y.; Fang, H. Hierarchical education investment and economic growth in China. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 112–125. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wye, C.K. The Effect of Investment in Education on China’s Economic Growth: The Role of Financial Development. Chin. Econ. 2022, 56, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Q. Sustainable Development of Chinese Industrial Clusters and Public Policy Choices. China Ind. Econ. 2005, 9, 5–10+33. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. From quantitative “demographic dividend” to qualitative “human capital Dividend” (Also on the power transformation mechanism of China’s economic growth). Econ. Sci. 2016, 5, 5–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, D.; Shrestha, D.P. Investment in education and its impact on economy of Nepal (An empirical analysis of educational spending to agriculture productivity). J. Adv. Acad. Res. 2017, 2, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, J.; Tan, N. Research on the spillover effect of higher education investment and human capital structure on regional economic growth. Heilongjiang Res. High. Educ. 2021, 39, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H. Sustainable development: The colors of sustainable leadership in learning organization. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Arsani, A.; Ario, B.; Ramadhan, A. Impact of Education on Poverty and Health: Evidence from Indonesia. Econ. Dev. Anal. J. 2020, 9, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ding, H. The current situation and existing problems of sustainable development of competitive sports in China. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 2000, 2, 8–11+22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, J. On the Reserve Talent Resources and Sustainable Development of Competitive Sports. J. Shanghai Inst. Phys. Educ. 2003, 1, 1–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, P.; Yang, R. Government investment in education, human capital investment and the income gap between urban and rural areas in China. J. Manag. World 2010, 1, 36–43. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen-Tsang, A.W.; Ku, B.H.; Wang, S. Social Work Education as a Catalyst for Social Change and Social Development: Case Study of a Master of Social Work Program in China. In Global Social Work: Crossing Borders, Blurring Boundaries; Noble, C., Strauss, H., Littlechild, B., Eds.; Sydney University Press: Sydney, Australia, 2014; pp. 283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hien, P.V. Public Investment in Education and Training in Vietnam. Int. Educ. Stud. 2018, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Frugal innovation embedded in business and political ties: Transformational versus sustainable leadership. Asian Bus. Manag. 2023, 22, 2225–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Gan, H. On the Relationship between the Concepts of Reasonable Allocation and Carrying Capacity of Water Resources and Sustainable Development. Prog. Water Sci. 2000, 3, 307–313. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wang, R. Ecosystem service functions, ecological values, and sustainable development. World Sci. Technol. Res. Dev. 2000, 5, 45–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zayyat, F.M. Impact of Education Expenditure on Cognitive Determinants of Sustainable Development The status of Arab Countries according to the International Development Indices. J. Educ. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 14, 13–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M. Investigating the linkages of female employer, education expenditures, renewable energy, and CO2 emissions: Application of CS-ARDL. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 61277–61282. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, C.; Wu, Q.; Cai, Q.; Li, G.; Jiang, C. On the Agricultural Resource Utilization and Sustainable Development of Urban Sludge. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000, 1, 158–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanger, N.R.G. Moving ‘Eco’ Back into Socio-Ecological Models: A Proposal to Reorient Ecological Literacy into Human Developmental Models and School Systems. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2011, 18, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Akesson, B.; Burns, V.; Hordyk, S.R. The Place of Place in Social Work: Rethinking the Person-in-Environment Model in Social Work Education and Practice. J. Soc. Work. Educ. 2017, 53, 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Zou, Y. Green university initiatives in China: A case of Tsinghua University. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 491–506. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, C.; Dewancker, B. A study of development mode in green campus to realize the sustainable development goals. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 799–818. [Google Scholar]

- Mturi, A.J.; Fuseini, K. Repositioning South Africa to Implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: A Demographic Perspective. S. Afr. J. Demogr. 2016, 17, 199–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hytten, K. Rethinking Aims in Education. J. Thought 2006, 41, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Meskill, D. Promoting a Skilled Workforce. In Optimizing the German Workforce: Labor Administration from Bismarck to the Economic Miracle, 1st ed.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 42–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, H.A. Education and socialization: A study of social importance of education in the development of society. Asian J. Multidimens. Res. 2019, 8, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, M.T.; Smith, C.L.; Leverenz, T. Quality of Life and the Carbon Footprint: A Zip-Code Level Study Across the United States. J. Environ. Dev. 2021, 30, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X. Education and Income Inequality: An Empirical Study in China. Manag. World 2004, 6, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 6th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdenberg, A.; Romeu, R. Parameter Estimate Uncertainty in Probabilistic Debt Sustainability Analysis. IMF Staff Papers 2010, 57, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L.; Lütkepohl, H. Vector Autoregressions: Uses and Interpretation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Analysis of factors influencing the price of Beijing carbon emission allowance based on the VAR model. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2025, 8, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xue, X.; Fan, X.; Chen, Q. An Empirical Study on the Impact of Education Input Output on Income Gap in China. Econ. Manag. Rev. 2024, 40, 136–149. Available online: https://www.chndoi.org/Resolution/Handler?doi=10.13962/j.cnki.37-1486/f.2024.02.011 (accessed on 27 March 2025). (In Chinese).

- Ding, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, W. The Social Returns of University Education: Expansion of Enrollment and the Spillover Effect of Human Capital. Economics (Quarterly) 2024, 24, 412–430. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qiu, B.; Wu, L.; Peng, T. Accumulation of Human Capital, Trade Openness, and Innovation in Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises. Economics (Quarterly) 2024, 24, 379–394. Available online: https://www.chndoi.org/Resolution/Handler?doi=10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2024.02.03 (accessed on 27 March 2025). (In Chinese).

- Criqui, P.; Russ, P.; Deybe, D. Impacts of Multi-Gas Strategies for Greenhouse Gas Emission Abatement: Insights from a Partial Equilibrium Model. Energy J. 2006, 27, 251–273. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Code | Data Sources | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | ||||

| The ratio of education funding to GDP | ei | Official website database of National Bureau of Statistics of China | 0.0488 | 0.0032 |

| Schooling years per capita | lc | UNDP Human Development Report database | 7.6326 | 0.7034 |

| Gini coefficient of disposable income per capita | se | Official website database of National Bureau of Statistics of China | 0.4754 | 0.0092 |

| Carbon emission per capita | ce | The World Bank Databank | 6.2564 | 1.3643 |

| The United States | ||||

| The ratio of education funding to GDP | uei | The World Bank Databank | 0.0591 | 0.0067 |

| Schooling years per capita | ulc | UNDP Human Development Report database | 13.5151 | 0.2232 |

| Gini coefficient of disposable income per capita | use | The World Bank Databank | 0.4088 | 0.0050 |

| Carbon emission per capita | uce | The World Bank Databank | 16.7827 | 1.9700 |

| Explained Variable | Results Based on Chinese Data | Results Based on the United States’ Data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explanatory Variable | dei | dlc | dse | dce | duei | dulc | duse | duce | |

| DEI (−1) | −0.45377 | −0.01684 | −0.03571 | 0.52884 | 0.271611 | −0.008 | −0.13939 | −0.05493 | |

| [−1.55383] | [−0.20094] | [−0.27943] | [2.07067] | [0.66893] | [−0.91270] | [−2.77315] | [−0.29241] | ||

| DEI (−2) | −0.33036 | 0.10166 | −0.0368 | 0.283974 | −0.31066 | 0.002568 | 0.004702 | −0.03079 | |

| [−1.26468] | [1.35597] | [−0.32185] | [1.24303] | [−0.94986] | [0.36365] | [0.11614] | [−0.20347] | ||

| DLC (−1) | 0.224503 | 0.678307 | −0.50467 | −0.92245 | 16.82513 | 0.369055 | −2.52884 | −4.26985 | |

| [0.19113] | [2.01211] | [−0.98171] | [−0.89799] | [0.97355] | [0.98898] | [−1.18207] | [−0.53404] | ||

| DLC (−2) | −3.48881 | −0.41236 | 0.317742 | −1.57815 | −7.1577 | 0.249097 | 2.907098 | 4.491658 | |

| [−1.88664] | [−0.77697] | [0.39260] | [−0.97584] | [−0.49426] | [0.79662] | [1.62168] | [0.67043] | ||

| DSE (−1) | −1.33274 | −0.26719 | 0.039017 | 1.408128 | −6.33655 | −0.0039 | 0.746142 | 3.451227 | |

| [−1.86240] | [−1.30097] | [0.12458] | [2.25002] | [−1.92707] | [−0.05495] | [1.83312] | [2.26872] | ||

| DSE (−2) | −1.061994 | −0.151582 | −0.321017 | 0.730957 | 0.260544 | −0.08727 | −0.87572 | 0.765893 | |

| [−1.46003] | [−0.72611] | [−1.00839] | [1.14907] | [0.11646] | [−1.80662] | [−3.16224] | [0.74001] | ||

| DCE (−1) | −0.23986 | −0.06274 | −0.04171 | 0.388943 | −0.16326 | −0.00504 | 0.091278 | −0.56308 | |

| [−0.63904] | [−0.58245] | [−0.25390] | [1.18489] | [−0.22544] | [−0.32216] | [1.01819] | [−1.68062] | ||

| DCE (−2) | 0.145416 | 0.037773 | 0.043463 | −0.25508 | 1.193776 | −0.01193 | −0.51792 | −1.59133 | |

| [0.53903] | [0.48786] | [0.36812] | [−1.08117] | [1.10301] | [−0.51032] | [−3.86581] | [−3.17818] | ||

| C | 0.070539 | 0.011068 | 8.90 × 10−5 | 0.070201 | −0.00752 | 0.000246 | −0.01439 | −0.07596 | |

| [1.79070] | [0.97899] | [0.00516] | [2.03776] | [−0.16044] | [0.24306] | [−2.48134] | [−3.50407] | ||

| R-squared | 0.665892 | 0.713399 | 0.27278 | 0.838056 | 0.499583 | 0.750175 | 0.855958 | 0.706677 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Hu, X. Dynamic Effects of Education Investment on Sustainable Development Based on Comparative Empirical Research Between China and the United States. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073068

Zhao J, Li Q, Hu X. Dynamic Effects of Education Investment on Sustainable Development Based on Comparative Empirical Research Between China and the United States. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073068

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Junjing, Qi Li, and Xiaobing Hu. 2025. "Dynamic Effects of Education Investment on Sustainable Development Based on Comparative Empirical Research Between China and the United States" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073068

APA StyleZhao, J., Li, Q., & Hu, X. (2025). Dynamic Effects of Education Investment on Sustainable Development Based on Comparative Empirical Research Between China and the United States. Sustainability, 17(7), 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073068