Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rural Depopulation: Global and National Context

1.2. Gender, Identity, and Sense of Belonging in Rural Contexts

1.3. Research Questions and Operationalization of the Object of Study

- To what extent is the perception of identity and belonging in rural “depopulated Spain” related to gender?

- How does gender influence the perception, use, and management of the natural environment in rural communities?

- What are the gender differences in the perception of risks and challenges facing rural areas and their possible solutions?

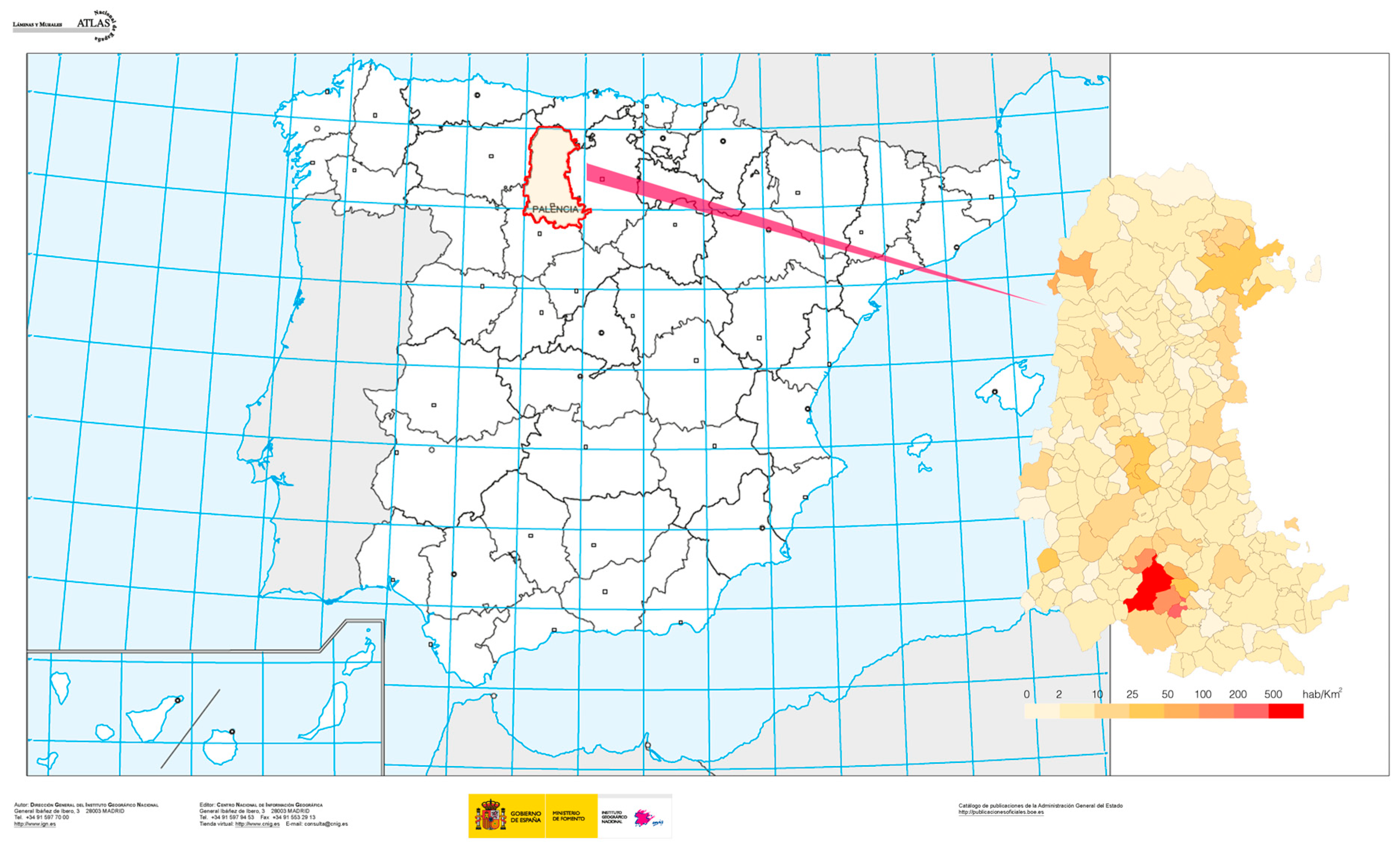

1.4. Demographic and Geographic Context

1.5. Educational Applications of the Research

- Social mapping works created during the study, reflecting participants’ narratives on identity, depopulation, and the transformation of rural spaces;

- Didactic material from “Pebbles of Memory”, which demonstrates how these topics were adapted to young students;

- Artistic expressions related to rural memory and sustainability, further connecting research results with public engagement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

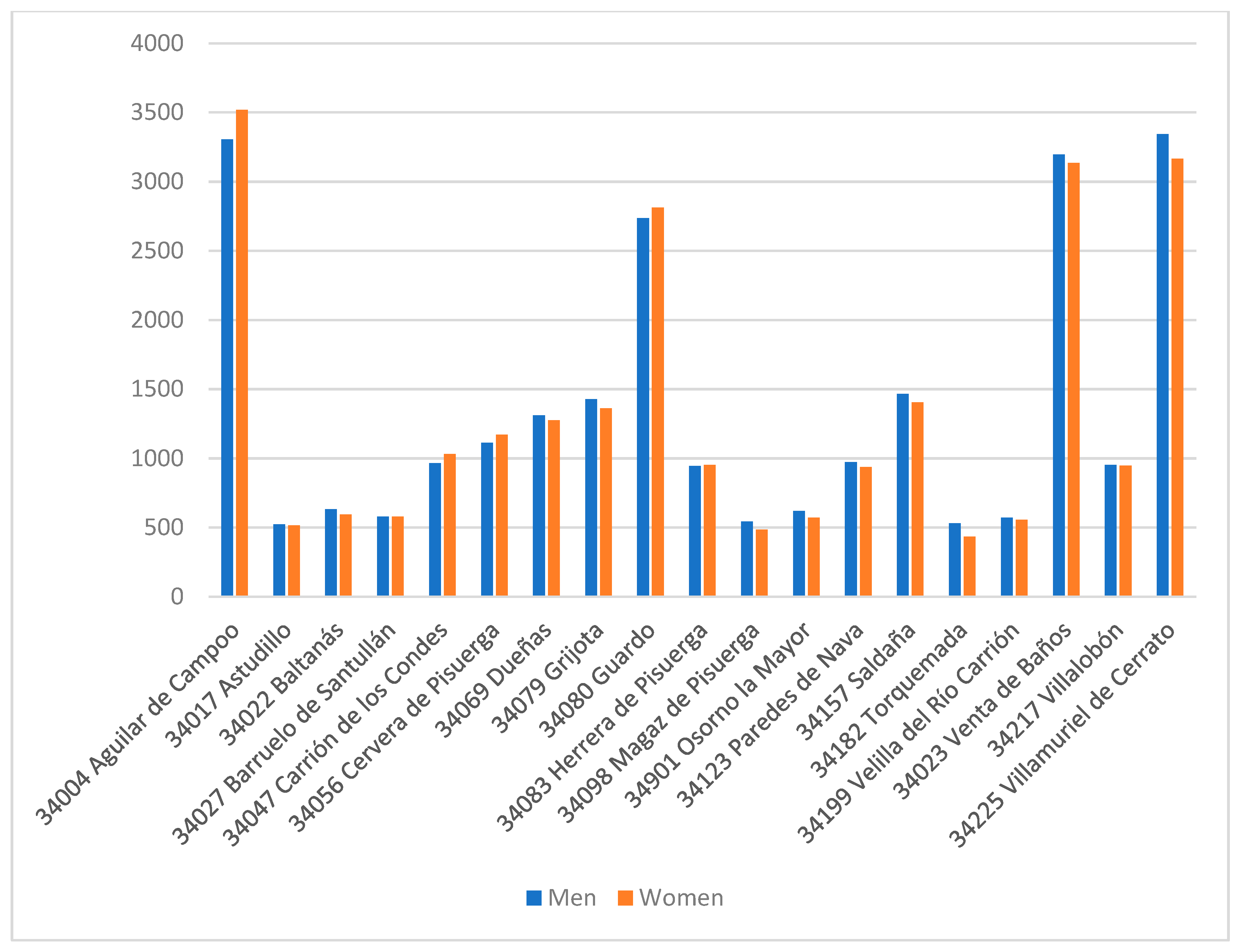

2.2. Participants

- Under 35 years old (n = 28)

- Median age (35–59 years) (n = 31)

- 60 an older (n = 31)

- Representativeness and other eligible participants

- Inclusion criteria

- a.

- Be 18 years of age or older;

- b.

- Have resided for at least 10 years in towns in Palencia affected by depopulation;

- c.

- Have permanent residence or close family ties to the town;

- d.

- Demonstrate willingness to participate voluntarily and provide detailed information about their experiences in the rural context.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3.2. Social and Participatory Mapping

- Can you describe places in your town that have significance and why?

- How do you think your relationship with these spaces has changed over time?

- Do you perceive differences in the way men and women interact or value certain places in the community?

- Are there particular areas that you associate with traditions, community events or collective memory?

- How has rural depopulation affected these areas?

2.3.3. Mapping and Data Collection Process

- Places of collective memory and social interaction (e.g., community events, traditional meeting points);

- Areas of environmental concern or transformation (e.g., degraded lands, conservation areas or sites affected by depopulation);

- Gendered spaces (e.g., places perceived as central to male or female social roles).

2.3.4. Interview Context and Ethical Considerations

2.3.5. Key Interview Topics

- Personal and geographic background: Participants were asked about their age, place of origin and current residence, as well as their perception of rural life, including sensory descriptions of their village (landscape, sounds, traditions) and significant personal anecdotes.

- Identity and sense of belonging: Participants reflected on how they perceive their connection to their community, what aspects define their sense of rootedness, and whether they have experienced changes in their sense of belonging over time.

- Perception of the natural environment: Interviews explored how men and women value and interact with nature, whether their relationship with the land is emotional or utilitarian, and how gender perspectives shape environmental conservation and land use.

- Depopulation and migration experiences: In the case of participants who had migrated to urban areas, questions asked about their motivations for leaving, their expectations of the reality of the city, and whether they would have stayed if local employment and services had been available.

- Challenges and rural revitalization: This study investigated participants’ perspectives on the risks and challenges facing rural communities, their views on possible solutions, and how gender influences responses to depopulation.

2.4. Procedure

2.4.1. Data Collection

2.4.2. Open Coding

2.4.3. Axial Coding

2.4.4. Selective Coding

2.5. Validity and Reliability Strategies

2.5.1. Source Triangulation

2.5.2. Validation with Participants

- Diversity of perspectives: Participants were chosen to represent different age groups, genders, and geographic locations within rural Palencia to ensure a validation process.

- Participation in the study: Priority was given to people who demonstrated a higher level of reflection and commitment during the interviews, as they were able to provide more detailed comments on the interpretations.

- Availability and willingness to participate: Only those who were willing and available at the time of validation were included.

2.5.3. External Audit

2.5.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

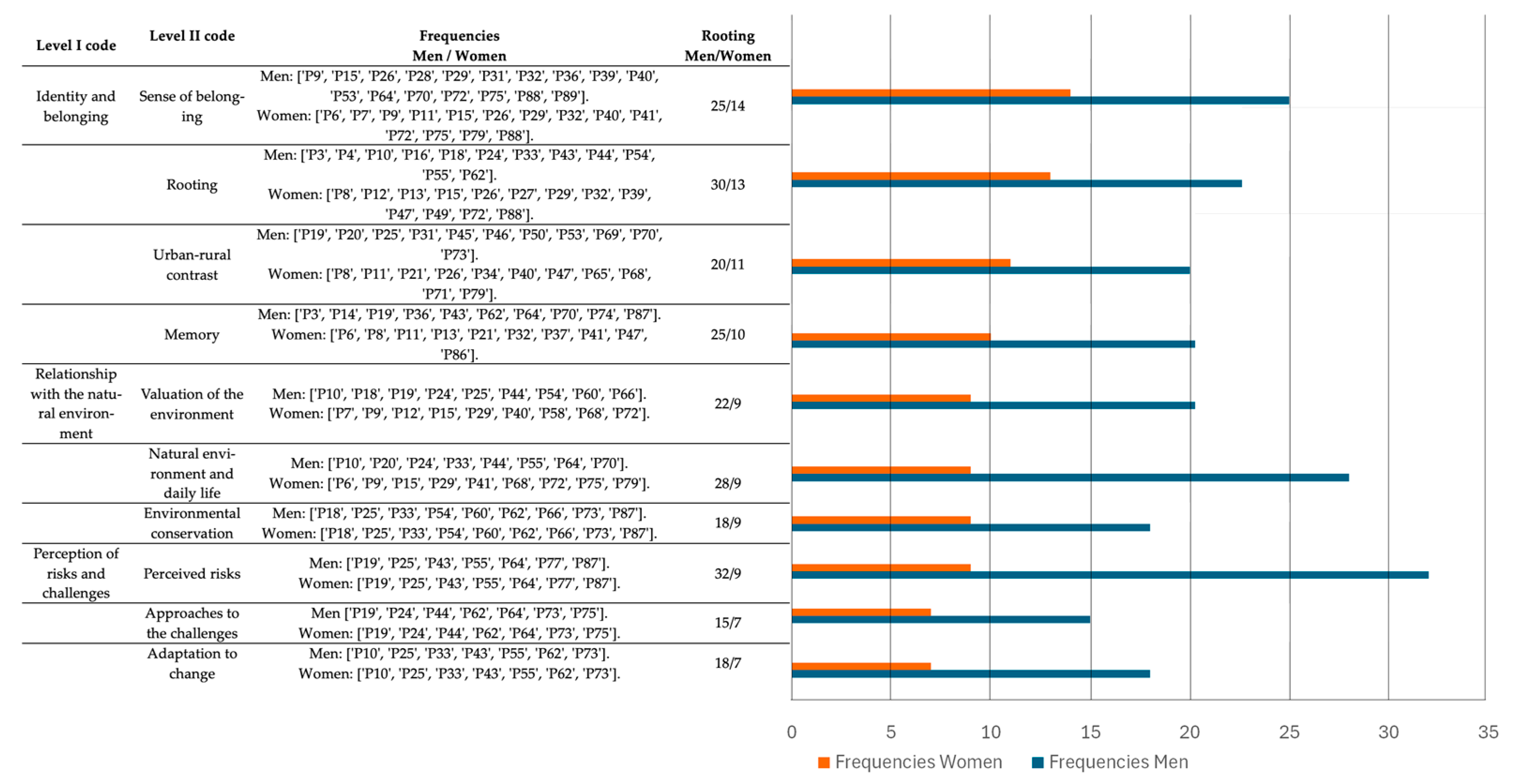

3.1. Identity and Belonging

“My role here is to follow in my father’s footsteps, to take care of the land he left us and to make sure there is no shortage of anything at the village festivals”.

“For me, the village is the place where I grew up surrounded by people who know me, who have watched my children grow up, and where I know I will never be alone”.

“Here you have to keep the family name and the place that the family holds in the community; that’s what we were always taught, and that’s what I want to leave to my children”.

“My grandmother’s and mother’s stories are part of who I am; they taught me what it means to belong here, and I like to think it continues inside me”.

“In the city, people forget where they come from; here, we always know who we are and where we come from”.

“The memories I have are of when we all worked together during the harvest; those days were the best because the village was united”.

“My memories are filled with afternoons spent with my mother and aunts, sewing and telling stories; those things are the heart of this place for me”.

3.2. Relation to the Natural Environment

“The village is, for me, a haven of peace, an oasis to stop and breathe”.

“It is a good town, welcoming and well cared for; it has fed several generations”.

“I remember the walks and excursions I took with my children, teaching them the value of taking care of the river and the trees. They talk to you, they are part of us, they have a language that is also ours”.

“In 1981 I got married and bought my in-laws’ land to work it again. I would like to create new crops and move into the production of processed products, but it’s not easy”.

“The smell of the wet earth gives me peace and joy; when the rain returns, everything germinates again”.

“The climate and the quality of the soil determine what can be produced each year and what the harvest will be like. I like rain, cold and dry heat, but each thing in its own time”.

“I don’t like that the river is not as clean as it used to be. It’s something I want to preserve for my children and grandchildren. Water is life”.

“If the land wears out, it won’t produce like it used to; we have to find a way to make it yield more”.

3.3. Perceived Risks and Challenges of Depopulation

“I do not see myself doing anything but cultivate; I do not know how to do anything but plant and harvest; I live on it and I will die on it. What can exist for me beyond my land?”.

“It is good that there are different jobs in town, we need more variety for families to stay. Today you can’t live off the land alone; there are better communications, more possibilities. We have to open ourselves to the future. I’m not saying it’s easy, nothing is, but either we do it or we die. That’s the way things are”.

“The important thing is to have work so that young people don’t leave, because ‘before there was work in the countryside for everyone, now almost no one stays, and the young people leave”.

“If we all work together, we can create spaces for our children and for those who come after us”.

“It would be good to have workshops for families and spaces where people can come together, talk, learn from the past, understand the present and imagine other possible futures, beyond loss and defeat”.

“In the city, people forget where they come from; here, we always know who we are and where we come from. In the countryside there is something—I wouldn’t know how to define it—that is authentic, and that something, honestly, I don’t find in city people”.

“I don’t see anything wrong with learning things from the city; I think we can be from here and there. You don’t have to leave town to be a well-rounded person”.

“I like my children to have Palencia friends; all my friends are from the village. Here, I am the outsider. I don’t want the same thing to happen to my children, that they grow up without roots. They should strive to belong here, and that means creating ties in the city”.

“Playing soccer with my coworkers helped me adjust. I did it every Friday afternoon and Saturday mornings. Playing soccer, having a drink, watching games... it’s something we all enjoy”.

3.4. Representativeness of the Perception of the City

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Methodological Contributions

4.3. Implications for Addressing Rural Depopulation

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implications for Research and Practice in Rural Contexts

5.2. Limitations of the Study

5.3. Future Lines of Research

- It would be beneficial to repeat this study in other rural communities with different cultural, geographic, and economic characteristics, as the comparison of the results in different rural contexts could help to identify common patterns and significant differences.

- In addition, longitudinal studies exploring how perceptions of gender, identity, belonging, and relationships with the environment evolve over time would provide valuable insights.

- A subsequent quantitative approach could enrich the analysis and offer a complementary perspective to this qualitative study.

- In addition, an interesting line of research would be to examine how age influences perceptions of identity and belonging, as it could help identify generational changes in gender perceptions.

- Finally, it would be valuable to investigate how rural development policies influence identity in order to design and implement gender-sensitive policies that support economic development, social cohesion, and emotional well-being in rural communities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Institute of Digital Publishing |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three-letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Alamá-Sabater, L.; Budí, V.; García-Álvarez-Coque, J.M.; Roig-Tierno, N. Using mixed research approaches to understand rural depopulation. Econ. Agrar. Recur. Nat. 2019, 19, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco de España. Informe Anual 2020: La Distribución Espacial de la Población en España y sus Implicaciones Económicas. 2020. Available online: https://www.bde.es/f/webbde/SES/Secciones/Publicaciones/PublicacionesAnuales/InformesAnuales/20/Fich/InfAnual_2020-Cap4.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Del Barrio, J.M. De los problemas a los retos de la población rural de Castilla y León. Encrucijadas. Rev. Crítica Cienc. Soc. 2013, 6, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero, L.; Oliva, J. Understanding rural change: Mobilities, diversities and hybridizations. Sociální Stud./Soc. Stud. 2016, 13, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasanta, T.; Arnáez, J.; Pascual, N.; Ruiz-Flaño, P.; Errea, M.; Lana-Renault, N. Spatio-temporal process and drivers of land abandonment in Europe. Catena 2017, 149, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Molino, S. La España Vacía: Viaje por un País que nunca fue; Turner: Madrid, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Soler, R.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Valenciano, J.D.P. Worldwide trends in the scientific production on rural depopulation: A bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix R-tool. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, L.; Hill, K. The gender dimension of agrarian transition: Women, men, and livelihood diversification. Gend. Place Cult. 2009, 16, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Rubio, M. Local place identity: A comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.; Chipuer, H.; Bramston, P. Sense of place among adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, L.S. Contextual variations in young women’s gender identity negotiations. Psychol. Women Q. 2003, 27, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent-Bedmar, V.; Palma, V.C.C.-D.; Navarro-Granados, M. The rural exodus of young people from empty Spain. Socio-educational aspects. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J. Rural depopulation, civil society and its participation in the political arena in Spain: Rise and fall of “Empty Spain” as a new political actor? In Win or Lose in Rural Development; Cejudo-García, E., Navarro-Valverde, F., Cañete-Pérez, J.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Verschuuren, B. Cultural and spiritual significance of nature in protected and conserved areas. The ‘deeply rooted bond’. In Cultural and Spiritual Meaning of Nature in Protected Areas; Verschuuren, B., Brown, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, J.; Campbell, R.C.; Lombrozo, A.; Wilson, D.M. The role of gender in belonging and sense of community. In Proceedings of the 2009 39th IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 18–21 October 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallés, M. Qualitative Techniques in Social Research. Methodological Reflection and Professional Practice; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Olabuénaga, J.I. Methodology of Qualitative Research; Universidad de Deusto: Bizkaia, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Council of Palencia. Strategic Plan 2020 of the Province of Palencia. Diputación de Palencia. 2020. Available online: https://www.diputaciondepalencia.es/sitio/promocion-economica/plan-estrategico-participacion (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- UN. General Assembly Adopts 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/2015/09/la-asamblea-general-adopta-la-agenda-2030-para-el-desarrollo-sostenible/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Jayalath, C. Application of Grounded Theory Method in Exploring the Discourse of Involuntary Resettlement and Challenges Encountered. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2023, 36, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L. Thinking About Data with Grounded Theory. Qual. Inq. 2018, 25, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vérez, M.V.; Sanchez Alba, B.; Gil-Ruiz, P. Social Cartography, an Art Education Proposal to Analyze Rural Depopulation from a Gender Perspective [Dataset]. Zenodo, 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14510064 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Kvale, Z. The Interview in Qualitative Research; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M.; Atkinson, P. Ethnography: Research Methods; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.M.G.; Jaber, M.; Sato, M. Social mapping and environmental education: Dialogues from participatory mapping in the Pantanal, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1514–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draucker, C.; Martsolf, D.; Ross, R.; Rusk, T. Theoretical sampling and category development in grounded theory. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Aguilar, V.; Miranda Mamani, P.; Tiayna Pacha, G.; Hidalgo Figueroa, E.; Tuna Varas, C. Sexual and gender diversity in educational communities in Arica, Chile: Fissure of heteronorma from multiculturalism. Lat. Am. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 15, 247–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques RF, R.; Júnior, W.M. Migration for Work: Brazilian Futsal Players’ Labor Conditions and Disposition for Mobility. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2020, 45, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Acuña, R.A.; Arzuaga, M.A.; Giraldo, C.V.; Cruz, F. Differences in data analysis from different versions of Grounded Theory. EMPIRIA J. Soc. Sci. Methodol. 2021, 51, 185–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, R.; Camarero, L. Immigrants, family strategies and rootedness: Lessons from the crisis in rural areas. Migrations 2016, 40, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashi Nulleshi, S.; Kalonaityte, V. Gender roles or gender goals? Women’s return to rural family business. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2023, 15, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C. Intergenerational gendered livelihoods: Marriage, matchmaking and Rural-Urban migration in China. Trans-Actions Plan. Urban Res. 2022, 1, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Sanchez, M.; Hoffman, J. Intergenerational strategies for preserving and appreciating the natural environment. In Intergenerational Pathways to a Sustainable Society. Perspectives on Sustainable Growth; Kaplan, M., Sanchez, M., Hoffman, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolache, E. Transforming gendered social relations in urban space. J. Res. Gend. Stud. 2013, 3, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Litina, A.; Moriconi, S.; Zanaj, S. The cultural transmission of environmental values: A comparative approach. World Dev. 2016, 84, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acselrad, H.; Núñez Viégas, R. Participatory social cartography: A theoretical approach to cartographic practices. Cuad. Geogr. Rev. Colomb. Geogr. 2022, 31, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Men | N | Average Age | DT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 39 | 53.7 | 21.96 |

| Women | 49 | 52.8 | 20.52 |

| Total | 88 |

| Level I Code | Level II Code | Frequencies Men/Women | Rooting Men/Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identity and belonging | Sense of belonging | Men: [‘p9’, ‘p15’, ‘p26’, ‘p28’, ‘p29’, ‘p31’, ‘p32’, ‘p36’, ‘p39’, ‘p40’, ‘p53’, ‘p64’, ‘p70’, ‘p72’, ‘p75’, ‘p88’, ‘p89’]. Women: [‘p6’, ‘p7’, ‘p9’, ‘p11’, ‘p15’, ‘p26’, ‘p29’, ‘p32’, ‘p40’, ‘p41’, ‘p72’, ‘p75’, ‘p79’, ‘p88’]. | 25/14 |

| Rooting | Men: [‘p3’, ‘p4’, ‘p10’, ‘p16’, ‘p18’, ‘p24’, ‘p33’, ‘p43’, ‘p44’, ‘p54’, ‘p55’, ‘p62’]. Women: [‘p8’, ‘p12’, ‘p13’, ‘p15’, ‘p26’, ‘p27’, ‘p29’, ‘p32’, ‘p39’, ‘p47’, ‘p49’, ‘p72’, ‘p88’]. | 30/13 | |

| Urban–rural contrast | Men: [‘p19’, ‘p20’, ‘p25’, ‘p31’, ‘p45’, ‘p46’, ‘p50’, ‘p53’, ‘p69’, ‘p70’, ‘p73’]. Women: [‘p8’, ‘p11’, ‘p21’, ‘p26’, ‘p34’, ‘p40’, ‘p47’, ‘p65’, ‘p68’, ‘p71’, ‘p79’]. | 20/11 | |

| Memory | Men: [‘p3’, ‘p14’, ‘p19’, ‘p36’, ‘p43’, ‘p62’, ‘p64’, ‘p70’, ‘p74’, ‘p87’]. Women: [‘p6’, ‘p8’, ‘p11’, ‘p13’, ‘p21’, ‘p32’, ‘p37’, ‘p41’, ‘p47’, ‘p86’]. | 25/10 | |

| Relationship with the natural environment | Valuation of the environment | Men: [‘p10’, ‘p18’, ‘p19’, ‘p24’, ‘p25’, ‘p44’, ‘p54’, ‘p60’, ‘p66’]. Women: [‘p7’, ‘p9’, ‘p12’, ‘p15’, ‘p29’, ‘p40’, ‘p58’, ‘p68’, ‘p72’]. | 22/9 |

| Natural environment and daily life | Men: [‘p10’, ‘p20’, ‘p24’, ‘p33’, ‘p44’, ‘p55’, ‘p64’, ‘p70’]. Women: [‘p6’, ‘p9’, ‘p15’, ‘p29’, ‘p41’, ‘p68’, ‘p72’, ‘p75’, ‘p79’]. | 28/9 | |

| Environmental conservation | Men: [‘p18’, ‘p25’, ‘p33’, ‘p54’, ‘p60’, ‘p62’, ‘p66’, ‘p73’, ‘p87’]. Women: [‘p18’, ‘p25’, ‘p33’, ‘p54’, ‘p60’, ‘p62’, ‘p66’, ‘p73’, ‘p87’]. | 18/9 | |

| Perception of risks and challenges | Perceived risks | Men: [‘p19’, ‘p25’, ‘p43’, ‘p55’, ‘p64’, ‘p77’, ‘p87’]. Women: [‘p19’, ‘p25’, ‘p43’, ‘p55’, ‘p64’, ‘p77’, ‘p87’]. | 32/9 |

| Approaches to the challenges | Men [‘p19’, ‘p24’, ‘p44’, ‘p62’, ‘p64’, ‘p73’, ‘p75’]. Women: [‘p19’, ‘p24’, ‘p44’, ‘p62’, ‘p64’, ‘p73’, ‘p75’]. | 15/7 | |

| Adaptation to change | Men: [‘p10’, ‘p25’, ‘p33’, ‘p43’, ‘p55’, ‘p62’, ‘p73’]. Women: [‘p10’, ‘p25’, ‘p33’, ‘p43’, ‘p55’, ‘p62’, ‘p73’]. | 18/7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Vérez, V.; Gil-Ruiz, P.; Montero-Seoane, A.; Cruz-Souza, F. Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073027

Martínez-Vérez V, Gil-Ruiz P, Montero-Seoane A, Cruz-Souza F. Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073027

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Vérez, Victoria, Paula Gil-Ruiz, Antonio Montero-Seoane, and Fátima Cruz-Souza. 2025. "Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073027

APA StyleMartínez-Vérez, V., Gil-Ruiz, P., Montero-Seoane, A., & Cruz-Souza, F. (2025). Rural Depopulation in Spain from a Gender Perspective: Analysis and Strategies for Sustainability and Territorial Revitalization. Sustainability, 17(7), 3027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073027