1. Introduction

In a village next to one of the authors’ homes, a new shopping center was built. The only new tree that appeared with it was an iron one. On the surrounding fields and meadows, new housing estates were built one after another, mainly gated communities. As we enter Warsaw, the capital of Poland, we see more and more oppressive architecture. Concrete and over-dense cities, suburbs, and villages with no space for anything except roads and parking lots are slowly becoming a reality for many cities. This view is shared by a number of concerned citizens. It is reflected not only in publications in the field of urban development [

1,

2,

3] but also in the content of the UN-Habitat agency’s report ’World Cities Report 2022: Envisaging the Future of Cities’ [

4]. However, this is not the end of the matter. Once, one of the authors shared her opinion on this subject with a fellow architect. He raised his head from blueprints and replied with sheer surprise: “Who cares?”. The authors have always thought that professionals involved in the development process should stand guard over an essential value—the livability of space for people and the environment. Are they wrong?

Why is the question of values important in the investment process, especially the process of space development? Whether it is about successfully combating climate change or making the neighborhood a livable, public space more friendly, the chain of action culminates often in the development stage. Here, the following question arises: can the participants of the process help counteract adverse changes? Can they, in a way, become custodians of the common good? And further

“quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” (who will guard the guards themselves?) [

5].

Land management is regulated not only by binding law but also a code of conduct for people and communities in the spirit of values. Here lies the need for actual knowledge, good will, reliability, imagination, and the desire to support a good cause. Someone initiates urban projects, someone pays for them, someone greenlights them, and someone benefits from them. This means that each participant in the development process, in some way, upholds the standards and values that will contribute to public benefit. The authors of this publication are not alone in their view. When addressing the construction industry’s management problem, non-financial factors that influence satisfactory business activity are raised. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) issues, combined with business ethics, become important for long-term company valuation, investment decision-making, and capital allocation. Key players of the investment and construction process must demonstrate to stakeholders and the public that they are committed to optimal performance when it comes to the basic triad: people, the planet, and profit [

6].

When studying the approach of other authors to the question of attitudes and values related to them as represented by participants in the construction investment process (CIP), several trends can be noticed.

The first one relates to the analysis of the attitudes of the participants (or, more broadly, stakeholders) of the CIP as an important human factor. This is the factor that goes beyond conventional economic and social approaches used to evaluate the investment process in designing projects and policies [

7]. In the context of CIP, all investment proposals and decisions are perceived as “human constructions” [

8].

Another trend focuses on the identification of attitudes that can improve the effectiveness of the CIP and is of an applied nature. Part of this research is aimed at finding the causes of inefficiency of the CIP [

9] and getting to the heart of problems and conflicts that hinder its efficient operation [

7]. Some authors point to the disruption of cooperation between CIP participants as the most significant professional and project execution in the construction industry [

10]. On the other hand, attention is paid to improving the efficiency of the CIP by emphasizing the role of its participants in maintaining the quality of work or achieving synergy resulting from their full cooperation. This is to be facilitated by the realization of the interests of all participants [

11]. Efficiency of the CIP, as a result of the attitudes of its participants, is also associated with obtaining a high-class final product [

12] and user satisfaction, which is largely influenced by the designers’ methodological workshop. Their professionalism is intended to arouse in users a satisfying perceptive experience and positive feelings [

13]. The authors also point out that the quality of work of the participants of the CIP and the ethics of their attitudes support the promotion of the investment process [

12].

The third research trend focuses on exploring the attitudes of CIP participants regarding their relationship to public benefits. This includes explaining attitudes and attitude changes towards promoting pro-environmental behavior [

14] and engaging more deeply in land-use management [

15]. The authors note that this can also be influenced by stakeholder perspectives, which impacts their preferences in this respect [

16]. In terms of considerations of the attitudes of CIP participants on public benefits, the authors are looking for optimal solutions for the triple bottom line of people, the planet, and profit [

6]. They also point to the importance of cooperation between the government and social capital to provide public goods based on ethical rights [

17]. When ethics are lacking in the attitudes of CIP participants, this results in the inefficiency of this process [

9].

A fourth trend is also notable. It points to the connection between ethics and the construction industry [

6] and values related to it. On the one hand, thanks to virtues such as trust, commitment, and reliability, the productivity of CIP increases [

10]. On the other hand, the authors point to a specific system created by value chain participants in construction [

18]. It is also interesting to look at the CIP as a system of creating value for the stakeholders themselves, which, as the authors note, cannot be separated from ethics [

19].

The study presented herein, although of a pilot nature and aimed at a preliminary verification of research assumptions and an assessment of the feasibility of the adopted methodology, will contribute to filling a research gap by identifying the attitudes and related values observed in participants of the CIP. Therefore, the authors designed a study aimed at exploring the attitudes and related values observed among participants in the Construction Investment Process (CIP) as a contribution to the discussion on values.

This study falls within the scope of basic research and aims to understand this phenomenon. The results of this study may, in the future, serve as a basis for conducting a broader research project.

At the outset, the following research questions were formulated: What types of attitudes and values can be taken into account? What will be the underlying theory for defining the attitudes and associated values of the CIP participants? Which attitude will prove to be leading? What values characterize the attitudes of individual groups of participants of the CIP?

Since this process is strongly linked to the law, industry standards, and technical sciences, it was assumed that it would primarily relate to values associated with a rational approach, tied to intellectual abilities, facts, proven technologies, and logical reasoning. In contrast, approaches based on a preference for subjective values and an intuitive or sensory approach may play a less significant role. It was also assumed that groups of participants with specialized education and creative skills would receive the most positive indications (descriptions).

This formulation maintains a direction that opens space for the exploration and interpretation of results within a qualitative approach.

2. Materials and Methods

In developing the research methodology, the focus was on three actions. The first involved selecting an underlying theory that comprehensively accounts for different approaches to reality. The second concerned the identification and recruitment of respondents. The third focused on choosing leading research methods and analyzing the obtained data (

Figure 1).

2.1. Basic Theory

In searching for the underlying theory to explore the attitudes of CIP participants related to values, the focus was on comprehensive approaches to perceiving reality that generate various mechanisms of cognition and orientation in reality.

First, attention was given to cognitive theories that describe the fundamental mechanisms of cognition and orientation in reality. One of these is Carl G. Jung’s theory, which addresses the four functions of the psyche and the resulting four approaches to reality that enable a person to orient themselves in the world [

20,

21]. These approaches are Thinking, Feeling, Perception, and Intuition (along with the associated positives and negatives). In turn, the Theory of Four Types of Knowledge, through which we acquire information about the world [

22], is related to the field of knowledge management. It identifies Explicit Knowledge, which involves rational–logical reasoning; Moral Knowledge, based on an ethical and emotional approach; Tacit Knowledge, which relies on intuition; and Embodied Knowledge, with its approach based on sensory experiences. The Ecological Epistemology Theory [

23] derives attitudes towards reality from a sense of our physicality. The author connects them with the body, environment, and sensory perception in direct contact with the world. When the element of cognition is affordances (perceived possibilities for action), logic and analysis dominate; when sensory experience is involved, sensory perception dominates; when interactions with the environment are involved, intuitive prediction dominates; and when practical action is involved, ethics and values dominate.

Considering theories that integrate different ways of perceiving reality, models can be distinguished that combine and classify various modes of cognition and awareness. In Wilber’s Integral Model of Four Consciousnesses [

24], the ways of perceiving reality include rational–logical ‘It-Science’; ethical, emotional, and subjective ‘I-Mind’; intuitive and inter-subjective ‘We-Culture’; and sensory and inter-objective ‘Its-Systems,’ with a focus on integral development and integral practice. Covey’s Model of Four Intelligences [

25] posits, among other things, that attitudes towards reality arise from different layers of thought. This model, aimed at holistic actions, identifies the following: Intelligence Quotient (IQ), Emotional Intelligence (EQ), Spiritual Intelligence (SQ), and Physical Intelligence (PQ).

Observing how ways of understanding reality change over the lifetime of individuals and societies, attention has been drawn to models describing the evolution of thinking and consciousness. In the Spiral Dynamics Theory by Graves [

26], it is assumed that individuals and societies develop through various levels of consciousness that are dependent on levels of existence. This development begins at a primitive level (focused on sensory survival) and continues through a tribal level (with intuitive–magical thinking); an egocentric level (dominated by strength and emotionality); a hierarchical level (ethical and moral principles); a rational level (logic and analysis); a pluralistic level (with empathy and cooperation); an integral level (where holistic thinking prevails); and finally, global consciousness, which integrates intuition, logic, ethics, and experience. Scharmer, in turn [

27], by considering the decision-making process, particularly in the context of implementing profound changes and innovations in change management, introduced the Theory U. It is characterized by a holistic approach, based on deepening processes and encompassing logic, ethics, intuition, and experience.

As a summary of the considerations, an approach was taken that views reality as complex systems in which different ways of understanding coexist and complement each other. An example is Senge’s Systems Thinking Model [

28], which presents reality as a network of interconnections. For its author, the key is the integration of rationality, ethics, intuition, and experience. According to this theory, ways of perceiving reality result from various aspects/elements of systems: structures and models are associated with logic and analysis, shared values and missions with ethics and morality, adaptations and foresight with intuition, and empirical learning with sensory experience.

In this framework, where each subsequent theoretical block develops the previous one—leading from basic cognitive functions to comprehensive systemic approaches—the theory that appears to give rise to the others is Jung’s theory. The later theories, to a greater or lesser extent, refer to Carl G. Jung’s four psychological functions: Thinking, Feeling, Perception, and Intuition. Moreover, in Jung’s theory, none of the four approaches were considered better or worse. His framework equated approaches based on emotions and values with those rooted in rational logic, the experience of pleasure, or the perception of relationships between elements of reality. Therefore, the authors considered it appropriate to make Jung’s theory the starting point for further research. The authors’ bold decision to follow his theory also resulted from Jung’s own suggestion. In ‘Man and His Symbols’ [

21], the philosopher encouraged readers to use the typology he proposed as a foundation for organizing different or new phenomena related to the human psyche. Taking the above into account, Jung’s theory was adapted for research and focused on four approaches towards reality and the values associated with them.

The first two approaches, described by Jung, thinking and feeling, are, in nature, both perceiving and evaluating reality. They are distinguished by different, contrasting points of view. In the thinking approach, intellectual abilities are used to adapt to people and circumstances. This type of attitude is evaluated by emphasizing objective assessments (“true”, “proven”, and “logical”) and is directed towards objective facts. In the feeling approach, it is about searching and finding one’s way through a different type of evaluation—feelings. It is the expression of one’s own opinions and intentions, a subjective assessment of values, and a selection of a love object following love, respect, or, for example, compassion. By means of the feeling approach, one subjectively decides whether something is pleasant or unpleasant, important or less important.

Using two consecutive approaches—perception and intuition—we perceive reality without evaluation. The perception approach facilitates observations of the surrounding world through the senses: events, phenomena, and people as they are. In this approach, we are interested in what we have in front of our eyes, and we live here and now without thinking about the meaning of events. We see the trees, not the forest. Perception gives birth to gourmets, refined aesthetes, and wonderful playmates who subordinate everything to joyful consumption.

The opposite of the perceptive approach is the intuitive approach. The intuitive type is able to derive information other than those coming from sensory impressions. They “get” the overall meaning of things; see the connections; and notice mood, causes, effects, and possibilities. The intuitive approach allows for capturing patterns, meaning, and significance, connection networks in the world around us, as well as the potential that lies in other people or new solutions.

To adapt Jung’s theory to the research problem in question, the term “approach” (the theory of four approaches to perceiving reality) and the term “attitude” (included in the title of this paper) were first defined. “Approach” is the way one treats someone or takes up something [

29]. “Attitude” is a behavior, judgment, or feeling towards various tangible and intangible entities (positive or negative, favorable or unfavorable) modeled by situational factors [

30]. The attitude towards a given entity is influenced by emotions, behavior, views, and knowledge about it [

31]. Both concepts speak about a person’s orientation towards an entity, but the term “attitude” includes a broader spectrum of meanings and values, as well as emotions. The authors decided that it would be more appropriate to connect it with the investment and construction process.

2.2. Sampling of Respondents

Another important element of this research concerns the participants of the CIP. They were selected based on Polish construction law [

32], because it is well known and deeply embedded in the Polish CIP environment, to which the survey respondents belong. Polish construction law lists the following groups of participants in the construction process: investor, designer, construction manager, and investor’s supervisory inspector.

For the purposes of this research, and for the sake of simplicity (while retaining the essence of their role in the investment and construction process), they were named as follows: investors, designers, contractors, and controllers. To this group, the authors added two groups of participants:

Theoreticians: scientists and creators of ideas and manifestos; they were included because the authors assumed that every action begins with an idea or concept (in line with the views of, among others, Plato [

33], Descartes [

34], and Kant [

35], as well as St. John with his well-known “In the beginning was the Word” (J 1:1) [

36]), which suggests that thoughts and ideas are primary to action.

End-users (hereinafter referred to as Users) of the facilities created in the construction process, such as houses, roads, workplaces, public utility buildings, as well as commercial and service facilities.

To sum up, based on Jung’s theory of four approaches to reality and the selected group of six participants of the CIP (Theoreticians, Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, and Users), this research aimed to determine the nature of the values noticed in the attitudes of the participants in this process by selected experts related to the area of Poland—the country of the authors of this study.

Due to the vast scope and complexity of the matter in question, the authors decided to conduct an exploratory study using individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with carefully selected professionals from six groups of CIP participants. Purposive convenience sampling, combined with elements of the snowball method, was used to identify willing respondents.

To reach the desired individuals, given the difficulty of penetrating this field, six key expert respondents were initially approached using arbitrary selection, guided by their own knowledge of this professional environment. The key informants (seeds) were professionals who met the following criteria:

They have at least ten years of professional experience and were recognized by the authors as respected and effective in their field.

They are active in the CIP within the Warsaw metropolitan area (the capital city).

They represent the private sector or the public sector, which includes state- and local government-owned enterprises, as well as, in the case of Users, the social sector (e.g., NGOs).

Next, each selected ‘seed’ was asked to suggest two relevant participants from the field—one from the private sector and one from the public sector—who met the following criteria:

They have at least ten years of professional experience and are known as respected and effective in their field.

They represent either the private sector or the public sector, which includes state- and local government-owned enterprises, as well as, in the case of Users, the social sector (e.g., NGOs).

From each key informant (seed), the snowball process expanded twice. As a result, each of the 12 participant subcategories (six main categories, each with two subcategories: private/public sector) included 36 individuals (three persons in each of the 12 subcategories), two of whom did not meet the established criteria. Therefore, the seeds were asked to suggest additional candidates to ensure that each category contained an equal number of participants.

From the resulting pool of experts, one person from each of the 12 categories was purposively selected. The final respondents were those who best met the sampling criteria and the research objectives. In cases where multiple individuals within the same subcategory equally met the criteria, the selection was made using simple random sampling. This occurred in four subcategories. Finally, twelve expert respondents (hereinafter referred to as respondents) were selected.

2.3. Data Analysis

The first stage of data collection involved conducting semi-structured individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) with each of the 12 respondents within the timeframe of May 2023 to January 2024. Interviews were conducted in Polish during face-to-face meetings or conversations on the Zoom platform. Each of them lasted, on average, about two hours and was documented manually (in accordance with verbal agreements with the respondents).

The framework for each conversation involved a set of initial questions aimed at obtaining targeted information from respondents in order to analyze their experiences and perceptions regarding what they valued most in the attitudes of each participant group—Theoreticians, Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, and Users—as well as what aspects of these attitudes they found most aggravating or annoying. The set of initial questions is presented in

Appendix A.

In the next stage of this research, inductive content analysis (primarily qualitative and to a lesser extent, quantitative) was used to examine the respondents’ statements, incorporating elements of thematic and sentiment analyses. A diagram illustrating the sequence of the conducted research and the methods used is presented in

Appendix B (

Table A1).

First, all documented statements were reviewed, and initial impressions were noted. Next, the analyzed content was divided into phrases relating to a single action, feature, or value. The total number of phrases was also counted.

In the next stage, the phrases were assigned to six groups of CIP participants: Theoreticians, Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, and Users (the number of phrases assigned to each group was also counted). Subsequently, each set of phrases belonging to the respective CIP participant groups was further categorized into four attitudes towards reality, based on C. G. Jung’s basic theory: Thinking, Feeling, Perception, and Intuition. For phrases that did not fit into the aforementioned attitudes, an additional thematic analysis was conducted. In the course of the research process, the four basic approaches to reality and the values associated with them were juxtaposed with the experts’ statements and further refined. The characteristics of attitudes and values were also expanded. As a result of these activities, two additional attitudes emerged: Creativity and Equilibrium.

The Equilibrium attitude originated during the initial stage of considerations regarding theories describing different approaches to reality. In many of these theories, including Jung’s theory, the importance of an integral, holistic approach was emphasized—where different ways of understanding coexist and complement each other [

20,

21,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. When phrases describing this type of approach appeared in the respondents’ statements, it was decided to expand the set of attitudes to include the Equilibrium attitude. On the other hand, the Creativity attitude originated from the values that respondents associated with the motivation for creative, expressive, and even artistic action, which could be linked to a kind of categorical imperative. The outcomes of such actions, born from the pure desire to create, did not fully align with Jung’s proposed attitudes—Thinking, Feeling, Perception, and Intuition. Therefore, it was decided to distinguish an additional category: Creativity. The characteristics of all

six attitudes, along with the values assigned to them, are presented in the Results section.

Upon completing this stage of the research, a manually conducted sentiment analysis by the researchers was undertaken. Using this method, the phrases assigned to the groups of Theoreticians, Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, and Users, as well as to the six attitudes towards reality—Thinking, Feeling, Perception, Intuition, Creativity, and Equilibrium—were categorized into those describing positive and negative characteristics. This kind of categorization is illustrated in

Table 1. At this stage, not only was the number of phrases assigned to each group counted but also the ratio of negative to positive descriptions.

In the final stage, the phrases within all categories were organized by grouping them into broader themes. Repetitive content was then consolidated and formulated in a way that accurately reflected the essence of the data.

Further research indicated the attitudes and values emerging from the phrases analyzed. Following a discussion of the research results, the most important conclusions and observations from the research were prepared.

Finally, a descriptive characterization of the six groups of CIP participants—Theoreticians, Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, and Users—was developed, focusing on their attitudes and the associated values.

3. Results

In the course of this study, the four attitudes, Thinking, Feeling, Perception, and Intuition, were enriched with additional values that are in line with those assigned to a given attitude by Jung (as presented above).

Based on the respondents’ statements, two further attitudes were identified: Creation and Equilibrium. They were described using values emerging from interviews with representative experts. What characterizes all six attitudes?

Thinking emphasizes objective assessments: “true”, “proven”, and “logical” (the values described by Jung are marked in gray). It respects facts, acting in accordance with professional knowledge, the law, and industry standards. Thinking orders facts and phenomena according to optimal conditions, quantification, and agency in light of the law and common sense (the above values are also accompanied by negatives).

Feeling subjectively decides whether something is “right” or “wrong”, important or less important. Since Jung classified values in the ethical and human sense in this group, the authors added empathy, commitment, and acting to it with a mission based on social good, social justice, and feelings: love, or other sentiments, as well as negatives (e.g., greed, hypocrisy, or negligence).

Perception facilitates the awareness of the surrounding world, the events, phenomena, and people through the senses and as they are. It is about senses, hedonism, beauty, and pleasure, or their opposites.

Intuition allows for capturing patterns, meaning, significance, and networks of connections in the surrounding world and also to notice cause-and-effect sequences, along with the opposites of the above-described values.

Creation is the value of creating something new for the sheer joy of the act of creation. It is the categorical imperative of a creator, searching for and opening up to “different and new” things, as well as sharing one’s discoveries (including the opposites of the above values).

Equilibrium involves striving for harmony, choosing mature solutions, taking balanced actions, thinking and acting on many platforms, covering a wide scope, and influencing the entire process, along with their opposites.

In the course of this research, 629 phrases were obtained, which were assigned to six groups of participants of the investment process. In a comparison, which took into account the number of phrases relating to individual participants (

Figure 2), it could be observed that respondents paid the most attention to two groups: Designers (170 phrases) and Investors (146 phrases). The fewest phrases were devoted to Theoreticians (69).

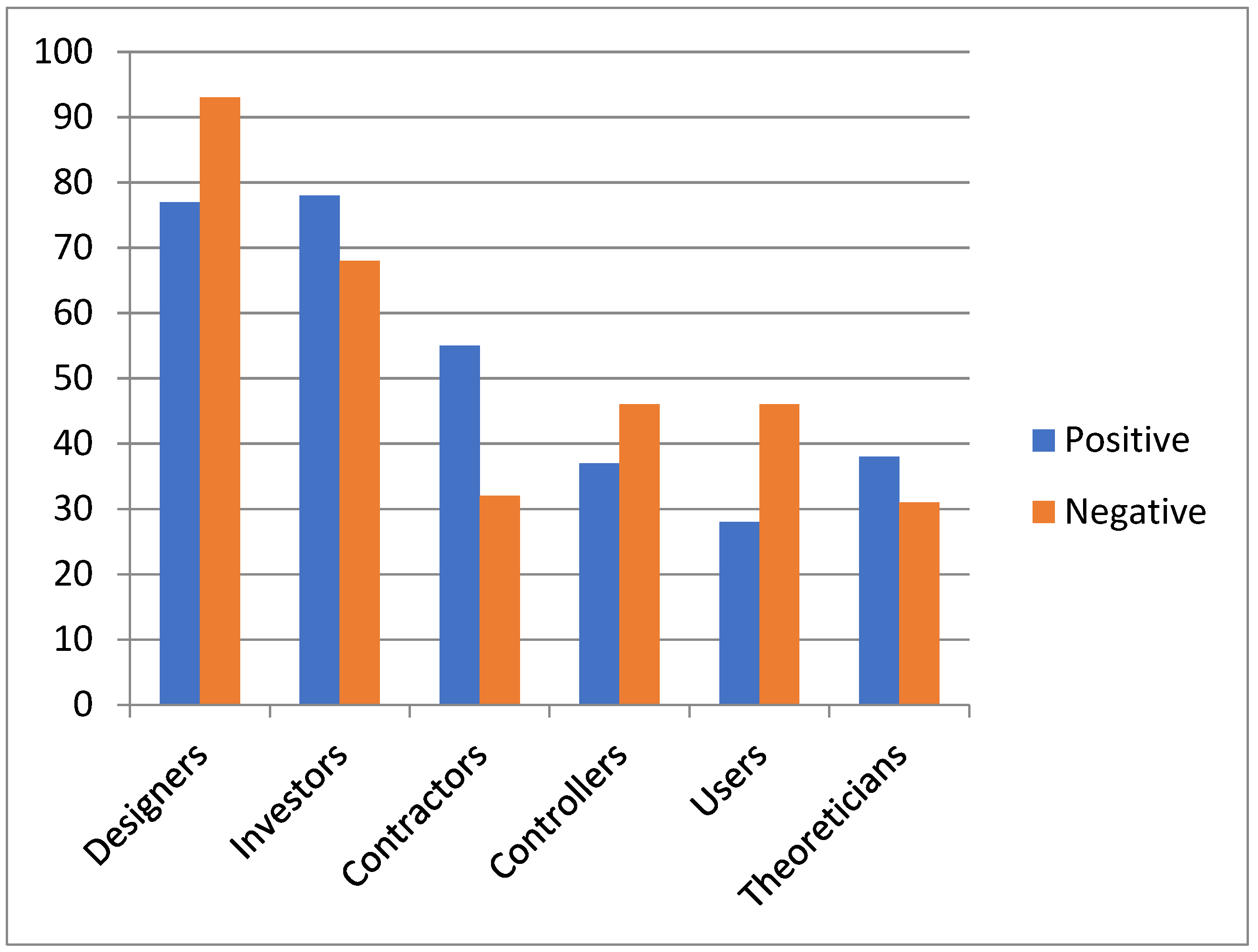

The phrases selected in this study concerned both positive and negative values observed/experienced by the respondents (

Figure 3). Overall, respondents indicated slightly more positive values than negative ones (316 phrases to 313).

The most positive phases were attributed to two groups: Investors (78 phrases) and Designers (77 phrases). The fewest phrases were associated with Users (28 phrases). On the other hand, the group with the most negative phrases was also Designers (93 phrases). The next group was Investors (68). The groups that collected the least number of negative phrases were Theoreticians (31 phrases) and Contractors (32 phrases).

The above lists of positive and negative values associated with the participants of the investment process must be supplemented with the relationships that can be observed in the individual groups of participants (

Figure 4).

The chart shows that the groups where negative values dominate in terms of the number of phrases describing positive and negative values are Users (28:46), Designers (77:93), and Controllers (37:46). The participants with dominant positive values are Contractors (55:32), Investors (78:68), and Theoreticians (38:31).

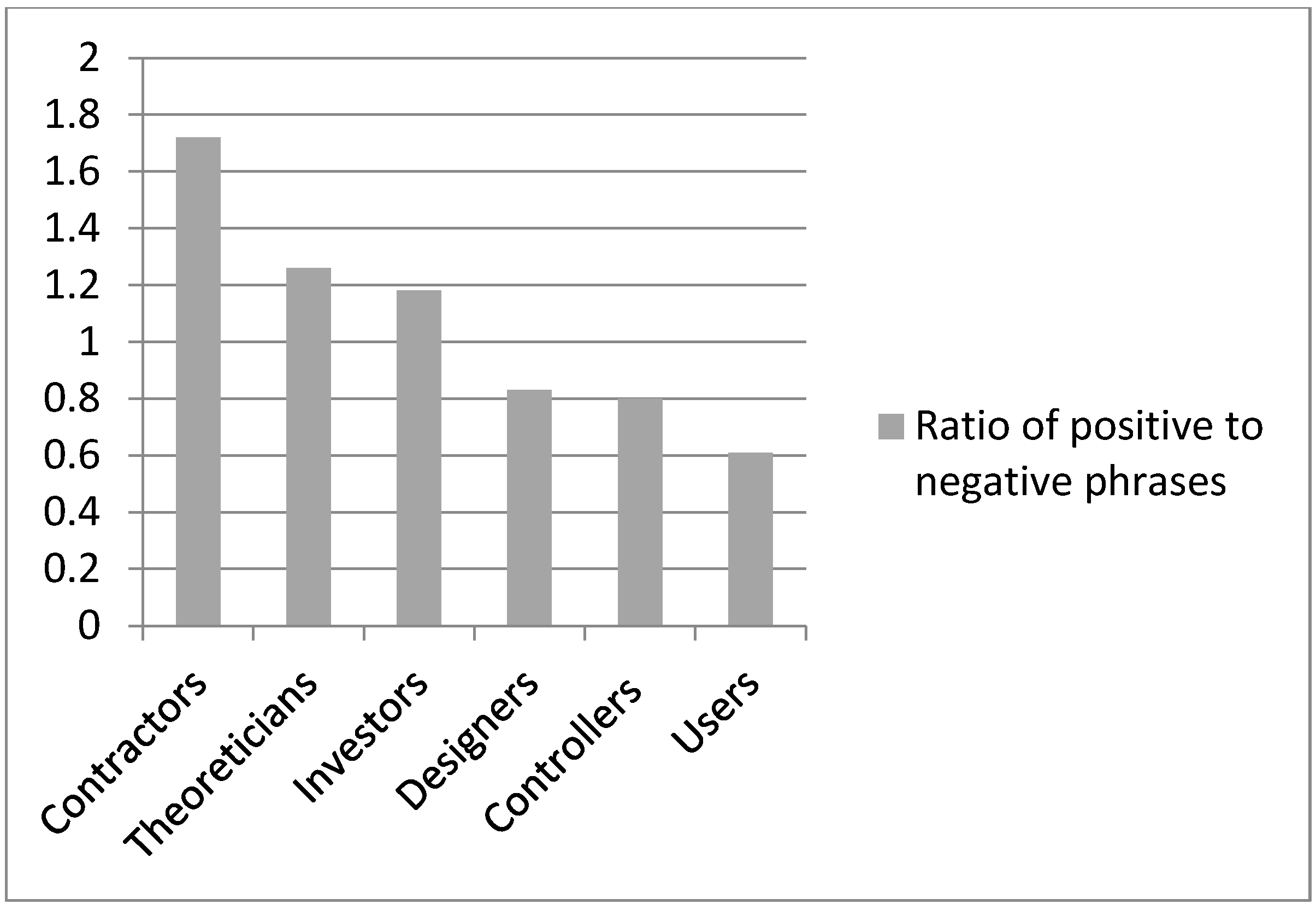

In terms of a ratio of positive to negative phrases, the highest was recorded for Contractors (1.72), Theoreticians (1.26), and Investors (1.18) (

Figure 5).

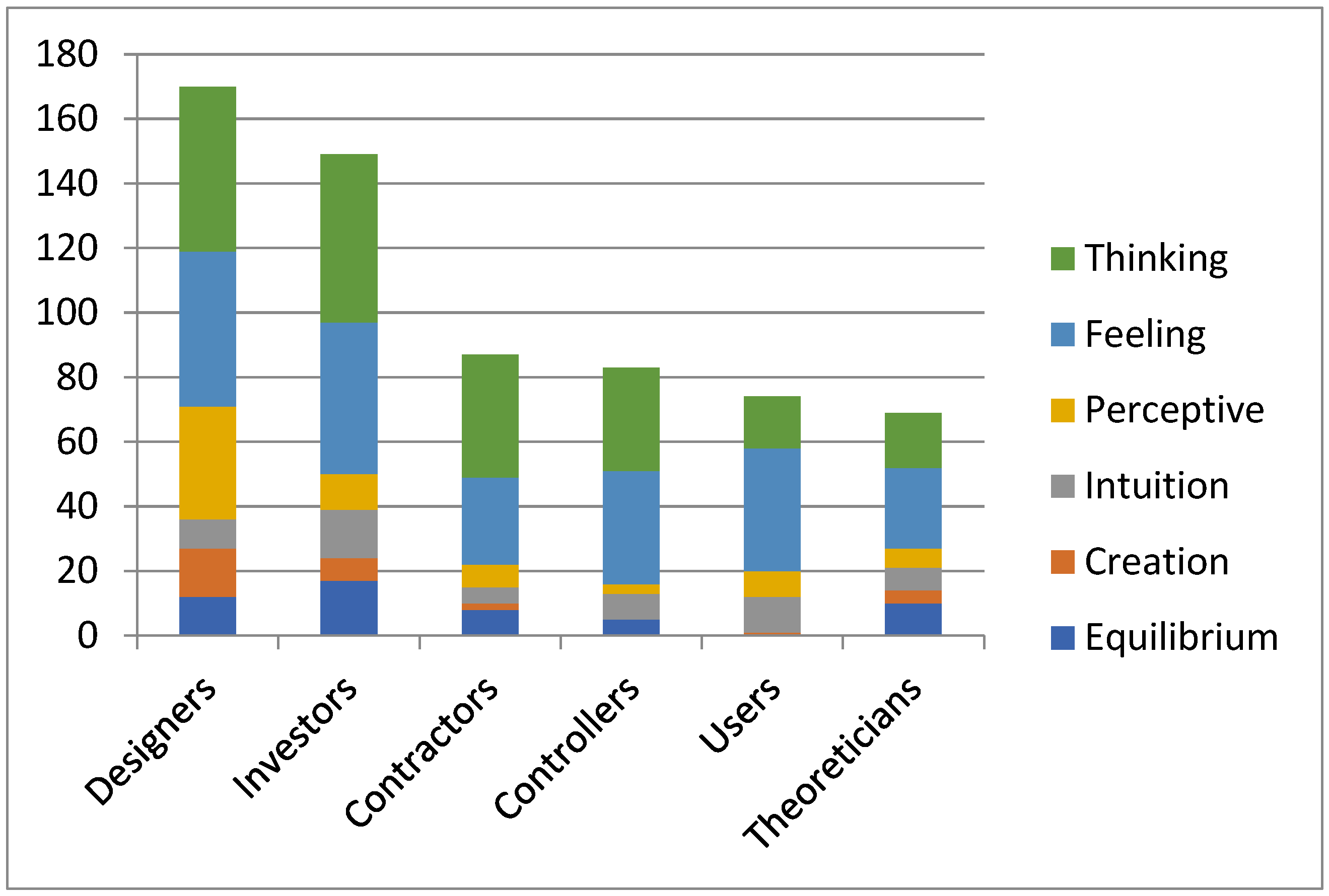

Taking into account the number of phrases assigned to individual attitudes and values that describe them (

Figure 6), the following dominate: Feeling (220 phrases) and Thinking (206 phrases). The next three attitudes are Perception (70 phrases), Intuition (55 phrases) and Equilibrium (49 phrases). The fewest phrases were assigned to Creation (29).

Looking at the number of phrases in the individual types of attitudes, a number of facts can be observed (

Figure 7). Most phrases related to Thinking were assigned to Investors and Designers, while the least were assigned to Users (16 phrases) and Theoreticians (17 phrases). Notably, the attitude Feeling is most often combined with Designers (48 phrases), Investors (47 phrases), Users (38 phrases), and Controllers (35 phrases). The participants who were assigned the fewest phrases related to Feeling were the Theoreticians (25 phrases). Perception clearly belongs to Designers (35 phrases). The largest number of phrases related to Intuition was assigned to Investors (15 phrases) and Controllers (11 phrases). The attitude Creation was the most frequently observed phrase attributed to Designers (15 phrases) and, secondly, Investors (7 phrases). No phrase related to Creation was noted in the Controllers’ attitude. Equilibrium was most often combined with Investors (14 phrases), Designers (12 phrases), and Theoreticians (10 phrases). In contrast, it was not reported in Users (0 phrases).

Below is a summary of the number of phrases in each type of attitude, expressed as a percentage (

Figure 8). The list below presents attitudes that significantly influence the characterization of individual CIP participants:

The Thinking attitude holds the largest share in the Contractors group (44%).

Feeling holds the largest share in Users (51%) and in Controllers (46%).

Perception and Creation hold the largest share in Designers (21% and 9%).

Intuition holds the largest share in Users (15%).

Equilibrium is most noticeable in Theoreticians (14%); it also constitutes a significant share in the group of Investors and Controllers (11%).

4. Discussion

The question of values and attitudes represented by participants of the CIP is linked to the view that the human factor is extremely important in this context [

7,

8,

11,

12,

18]. The research results confirm this view, despite the earlier assumptions noted in the hypothesis. It was assumed that this process, being strongly linked to the law, industry standards, and technical sciences, would mainly impact the values associated with the Thinking approach. The remaining approaches, Feelings, Perception, and Intuition, would prove to be marginal. When this study was first initiated, the authors were convinced that the experts’ statements would mainly highlight rational attitudes related to professional knowledge, logical thinking, facts, and the law. However, the research results show how important the emotional attitude related to the right or wrong, empathy, and commitment is, as well as acting with a mission based on social good, social justice, love, or sentiment. This is indicated by the fact that the percentage of phrases concerning values related to Feelings recorded in this study was higher than those related to Thinking (220:206). Therefore, it is fair to conclude that the main “human factor” in the attitudes of the CIP is the Feeling attitude.

The obtained characteristics of the attitudes of individual CIP participants is not strictly related to the problem of efficiency in the process raised by other authors [

7,

9,

11,

12]. However, it can be observed that the values indicated by experts could contribute to it. This is particularly visible in the case of negative values indicated by representative experts, such as wishful thinking, conformism, reliance on routine, giving up without a fight, making significant decisions without adequate education, unwillingness to learn, failure to deliver projects according to best practices, refusal to correct mistakes, disregard for design quality, the lack of broader knowledge and cause-and-effect thinking, fear of new technologies, and the postponement of recommended repairs or maintenance.

Furthermore, a number of values, referring to the effectiveness of the CIP also touched on the sphere of conflicts between the CIP participants observed by other authors [

7,

10]. These included, among others, greed, dishonesty, bending the law, manipulation, refusal to strive for agreement, cheating on costs, shifting responsibility to others, stubbornness when confronted with mistakes, underestimating opponents, triggering negative emotions, avoiding responsibility for errors, ignoring deadlines, encroaching on the areas of competence of other professionals, being aggressive towards competitors, and indulging in negative emotions and conflicts that solve nothing.

Many of the values identified by the representative experts pertain to positive traits that enhance the quality of work and, consequently, the efficiency of the CIP. They also include values associated with ensuring the high quality of the final product—the construction project or the finished facility. These included, among others, fostering a style of understanding; thinking outside the box; employing competent professionals and respecting their opinions; promoting cooperation and communication; relying on facts and logic; clearly presenting criteria, needs, and expectations; setting clear boundaries—legal, financial, ethical, and social—possessing expert knowledge, experience, and competencies in various fields; making work more coordinated and efficient; and using the language of technology and the law, along with common sense, moderation, partnership, and dialog. Although it was not the subject of this study either, CIP efficiency was also linked to the satisfaction of facility users [

13].

Many of the values described by the experts also pertain to the process itself. For example, good investors understand who their clients are and feel a sense of social responsibility towards users. They take pride in user satisfaction. A good investor respects social, cultural, and ethical values while considering the well-being of future users. Designers are attentive to people’s needs, and constructors have respect for users. During the constructing process, Controllers safeguard security and users’ rights.

This research also draws attention to an interesting phenomenon described by other authors. It consists of transforming knowledge, principles, and norms used in the designing process (i.e., professional activities belonging to the attitude Thinking) into the feelings and emotions of users [

13]. In our study, representative experts pointed out the process that takes place in the work of Designers. They “transform knowledge, emotions, experiences, sensations, intuition and creativity into real shapes and new technology”, as one of the representative experts put it. Therefore, “designers are both visionaries and engineers, creators and realists”. In addition, it has been shown that this process is preceded by a preliminary stage, where Designers themselves experience reality through their senses (Perception) and take into account values related to the attitude Feeling.

The experts also linked many values to public benefit activities, a topic also discussed by many authors [

6,

14,

15,

16,

17]. These values were associated with Theoreticians who formulate a “culture of speech”, direct the style of understanding by creating ethical norms, and by going beyond their own place and time, they “see local for global”. These values also concerned Investors who respect social, cultural, aesthetic, and ethical values and are no strangers to acting with a mission, as they think about the well-being of future users. Designers are also no strangers to public goods activities, as they respect the landscape, the place, and environment, similar to Controllers who safeguard security and user rights. Last but not least, Users can fight for the issues that are important to them (e.g., global warming or social public space).

In this study, the experts pointed to a number of values that connect the CIP (and, more broadly, the construction industry) with ethics [

6,

10,

19]. The word “ethics” appeared many times in the experts’ statements, also in the context of understanding by creating ethical norms. The research results also note negative values related to the lack of ethical standards among CIP participants. These included a lack of professional ethics, dishonesty, bending the law, falsifying costs, shifting responsibility to others, using misleading visuals to deceive investors and users, ignoring design quality, avoiding accountability for errors, introducing substandard materials and technologies, concealing mistakes, disregarding the consequences of their actions, breaking laws and rules, disrupting priorities, and engaging in corruption.

Considering the interesting conclusion of other authors that the CIP is a specific system of values, including ethics, created for the stakeholders themselves [

19], it must be said that this research confirms this finding.

While research hypothesis no. 1 concerned the attitude that would be assigned the most values, hypothesis no. 2 assumed that participants who would be assigned the most favorable ratio of positive to negative phrases would be Theoreticians and Designers due to their specialized education and creative competences. However, the research results indicate that participants who had a predominance of positive phrases were Constructors (especially companies providing comprehensive services and specialist companies) in the first group (ratio 1.72), Theoreticians in the second group (1.26), and Investors in the third group (1.18). What is interesting is that the group of participants with a predominance of negative phrases included Designers, with a ratio of 0.83. Users were last but not least (0.63).

The percentage share of phrases concerning particular attitudes assigned to individual groups of participants indicates the dominant sphere of influence. It turns out that there is no leading attitude that would be most pronounced among the majority (at least four) of participants. And so, the attitude Thinking is the most pronounced among Contractors, Feeling among Users, Perception and Creation among Designers, Intuition among Users, and Equilibrium among Theoreticians (also constituting a significant share among Investors and Controllers). It can be concluded that in terms of the values they recognize, the individual CIP participants complement each other.

Finally, the authors would like to draw attention to the views of two CIP participants (one from the group of Investors and one from the group of Constructors) regarding their motivation, which does not concern financial gains and industry awards. Instead, it stems from the gratitude of end-users, expressed through simple, spontaneous “thank yous,” and, on the other hand, from their care for the spaces they inhabit. This is because it gives them the feeling that they have really achieved something that is good.

5. Conclusions

To characterize the attitudes of six groups of participants of the CIP and the values associated with them, six groups of participants of the process were selected as a result of this research.

Also, six attitudes were formulated, which included the four indicated by Jung and two additional ones identified in the course of this research. These six attitudes were assigned values described/indicated by Jung and were selected in the course of this research by representative experts, in the spirit of Jung.

Taking into account the initial assumption regarding the assumed advantage of the attitude Thinking, it turned out that hypothesis no. 1 was not confirmed. The most frequently indicated attitude was Feeling, and only then came Thinking.

Referring to hypothesis no. 2 regarding the largest number of positive indications, it should be noted that the largest number of them was obtained by Designers. However, considering the fact that they received the largest number of phrases and the unfavorable ratio of positive to negative phases, Designers turned out to be the most controversial group. In turn, the participants whose attitude gained the most positive image (the best ratio of positive to negative phrases) were Contractors, especially companies providing comprehensive services and specialist companies. Thus, hypothesis no. 2 was partially confirmed.

The additional attitude identified—Creation—though it did not receive many entries, remains significant. It aligns with the global trend of developing soft skills and encouraging a creative approach to problem-solving in all areas of life.

Another additional attitude, Equilibrium, indicates the need for an attitude of dialog, balanced judgments and messages, multi-functional attitudes, interdisciplinary knowledge, broadly understood responsibility, agency and openness to diverse views, and needs in the CIP. The participant who is particularly predisposed to this attitude is the Investor.

In the conclusion of this research, a characteristic of attitudes of six groups of participants of the CIP (Investors, Designers, Contractors, Controllers, Users and Theoreticians) is presented as follows:

Theoreticians were the least important to the study’s respondents. On the other hand, please note that more positive than negative phrases were assigned to them (

Figure 3). Theoreticians have a special position—they are the first to

discover new phenomena and name them (unnamed things do not exist);

define the language to be used and formulate a “culture of speech”;

link in the path from theory to practice;

direct the style of understanding by creating ethical norms.

In addition, by going beyond their own place and time, they are able to “see local for global”. Thanks to their meta-view, they rise above dozens of problems to synthesize them. Being creative, they can afford to think outside the box.

If Theoreticians sin, they are plagued by the lack of imagination, empathy, “understanding the essence of the image”, routine, the desire for authoritarianism, and the “Besserwisser attitude”, in scientific terms. Their problem is also conformism, giving up without a fight, disregarding the “human factor”, intuitiveness, or beauty.

The position of the Investor gives the greatest control and power over the investment process. And the greatest responsibility. Investors are a driving force, which allows them to create the framework for the project.

A good Investor acts as a “creative producer”. They know what they are doing, and why. They also know who their client is (they feel socially responsible towards users and “are happy with their satisfaction”). A good Investor has intellect; respects social, cultural, aesthetic, and ethical values; and is no stranger to acting with a mission. They employ competent professionals and then respect their opinions.

Investors are responsible for the style of cooperation and communication (using facts and logic and clearly presenting criteria, needs, and expectations). They set clear boundaries: legal, financial, ethical, and social ones. The good Investor thinks about the well-being of future users.

The problem is that with such power over the investment process and control and enormous agency, Investors do not need to have special knowledge or authorization. The faulty logic of faulty laws prevails here: “people with no adequate education decide on many important things”. Other “sins” of the Investor include greed, lies, and bending the law.

If the Investors do not want to, they do not have to strive to reach an agreement, understand technologies, or learn about the needs of users. They do what they want, because “there is no one who will stop them”. Instead of communicating, they manipulate, remain in conflict, accept pseudo-aesthetics, and place others in “feudal dependence”.

The respondents’ attention was mostly focused on DESIGNERS (e.g., mainly architects but also interior and landscape designers, as well as architects). What impressed the experts (apart from designing the adequate form, function, and usability, as repeatedly noted) was the “soul of the project”. Designers can also reveal a world of unique forms, scenery, and images. They can demonstrate an unknown reality from a perspective that would never have occurred to their audience. They can also transform knowledge, emotions, experiences, sensations, intuition, and creativity into real shapes and new technology. The Designers are therefore both visionaries and engineers, creators, and realists. They are attentive to people’s needs, they respect the landscape, the place, and the environment (‘hug bats and salamanders’). They are interested in learning about phenomena, acquiring knowledge and experience, as well as creative thinking.

And everything would be great if it were not for their dark side. The results of this research indicate that Designers are a quite controversial group, which has received a lot of critical opinions. Some of the Designers

Can but do not want to learn, get involved, or have a mission or idea.

Should but do not deliver projects according to best practices, correct their mistakes, respect experts and the needs of users, and use their own resources.

And even if they can and want to do the above, in the pursuit of earnings, they have neither the time nor the space for it.

They should not but they do over-invest, manipulate costs, shift responsibilities to contractors and investors, act stubbornly when confronted with mistakes, dismiss their opponents as ignorant, follow trends blindly or resist change, take the easy route with “copy–paste” solutions, conform to investors’ demands, provoke negative emotions, prioritize their own vision over the well-being of the space, use attractive visuals to deceive clients, and replace genuine talent with arrogance.

They have to ensure, but ignore, the following: obligatory supervision, quality of design, responsibility for errors, and professional ethics and deadlines.

They lack broader knowledge, engineering sense, commitment, and “the essence of their profession”.

They exhibit inflated traits: an oversized ego, arrogance, greed, wishful thinking, and a tendency to encroach on the areas of expertise of other professionals.

The greatest positive surprise was the group of Contractors. While authors expected lots of negative feedback on this group, the Contractors (especially general contractors or highly specialized companies) received the highest percentage of positive comments. Contractors are currently at the forefront of new technologies. They have expert knowledge, experience, and competence in various areas, are necessary to correct design errors, pick up work after others, and make work more coordinated and efficient. They use the language of technology and the law, common sense and moderation, partnership, and dialog. Their path to success is cooperation and respect (for themselves and work, for the investors, employees, users, and for other professionals). They are creative and flexible in finding optimal solutions.

Among the negatives, in some cases, their lack of professionalism in terms of knowledge and competence stands out. Next is fear of new technologies, failing to fulfill contracts, ignoring the blueprints by introducing poor quality materials and technologies. Respondents spoke of a “culture of greed” that pushes Contractors to be dishonest, conceal mistakes, ignore the consequences of their actions and act aggressively towards competitors.

Controllers, due to their professional knowledge and experience, are able not only to control the quality of the work but also to be “a bridge” between the investor and the contractors. They speak the language of facts: they demand facts, rely on facts, score points according to facts, and are relentless in this respect. They not only evaluate but also propose pragmatic solutions to problems. In their case, the values associated with Intuition, especially cause-and-effect thinking, are not just an advantage but their essential attribute. (Please note that in Jung’s theory, described in the introduction, the “non-judgmental” character of Intuition was clearly emphasized. Nevertheless, Jung himself wrote about the possibility of combining two or more approaches to reality in the human psyche. In the case of Controllers, the essence of their professional attitude required the support of the Intuition attitude by the Thinking attitude.) During the constructing process, Controllers safeguard security and users’ rights. To perform their task, they need a balanced personality and high personal culture.

The shortcomings of this group often result from the lack of professional knowledge, competence, imagination, “unwillingness to learn” new things, and finally—the lack of professional ethics. This results in bending or even breaking the law and rules, the disruption of priorities, corruption, and the lack of respect for oneself and others.

Users have a lot of faults (the largest percentage of negative traits). In the opinions of our experts, they lack basic knowledge on technology, aesthetics, spatial order, and economics. They also show “mental laziness” to learn new things and indulgence in bad emotions and conflicts that solve nothing.

Users are stuck in a “culture of shortage”, as demonstrated in the consent to cheap materials and short-lasting technologies. It is also shown in their lack of imagination regarding the consequences of one’s actions, e.g., postponing recommended repairs or maintenance works.

However, it turns out that Users also have some strengths: first of all, they have “the power to make things happen”, because Users can fight for the issues that are important to them. Many users also have a lot of common sense and good ideas. Their creativity and “collective wisdom” are revealed during workshops conducted by specialists. It also turns out that users can encourage other participants in the process (Investors, Designers, and Contractors) by showing gratitude. This happens when Users send other CIP participants their thanks, honor them with awards, or spontaneously take care of places and facilities created for them.

6. Summary: Limitations, Significance, and Future Work

The study herein is not a global report. It is exploratory in nature and merely draws attention to certain phenomena. The authors hope that the results of this study will be a starting point for a discussion on effective CIP for public benefit. Our research, by addressing the attitudes of CIP participants and the values associated with them, is strongly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda. Considering the SDGs, our contribution to this issue represents a step towards improving quality of life (SDG 3), ensuring decent work (SDG 8), fostering innovation in the construction industry (SDG 9), and promoting the development of sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11). Moreover, it encourages people to take action for a sustainable environment (SDG 13) and, in line with values associated with the Equilibrium approach, supports partnerships for the goals (SDG 17). Looking at our research from a broader perspective, it is characterized by an interdisciplinary approach, integrating urban planning, environmental engineering, sociology, and spatial management. As an additional voice in the global debate on attitudes in CIP and the values associated with them, our findings also contribute to international cooperation. Thus, our study aligns with global efforts towards sustainable development.

The research presented here, as mentioned above, only outlines the problem of the importance of values in the scientific, design, and implementation processes related to construction investments. Therefore, research into professional ethics should be continued, with studies focusing on values for each of the previously described participants in the investment process. We also propose the need for research into the contemporary essence of values associated with Carl G. Jung’s particular approaches to reality. Treating the conducted study as a pilot study, this leads to the conclusion that in the future, this study should be extended to a representative study for the Polish CIP community. As mentioned at the outset, this merely constitutes a contribution to the ongoing discussion on attitudes and values in CIP. It would be valuable to explore how the addressed issues are approached in other countries, regions, or cultural contexts, as well as to gain insights into the profiles of CIP participants in those settings.