Assessing Income Heterogeneity from Farmer Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Initiatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

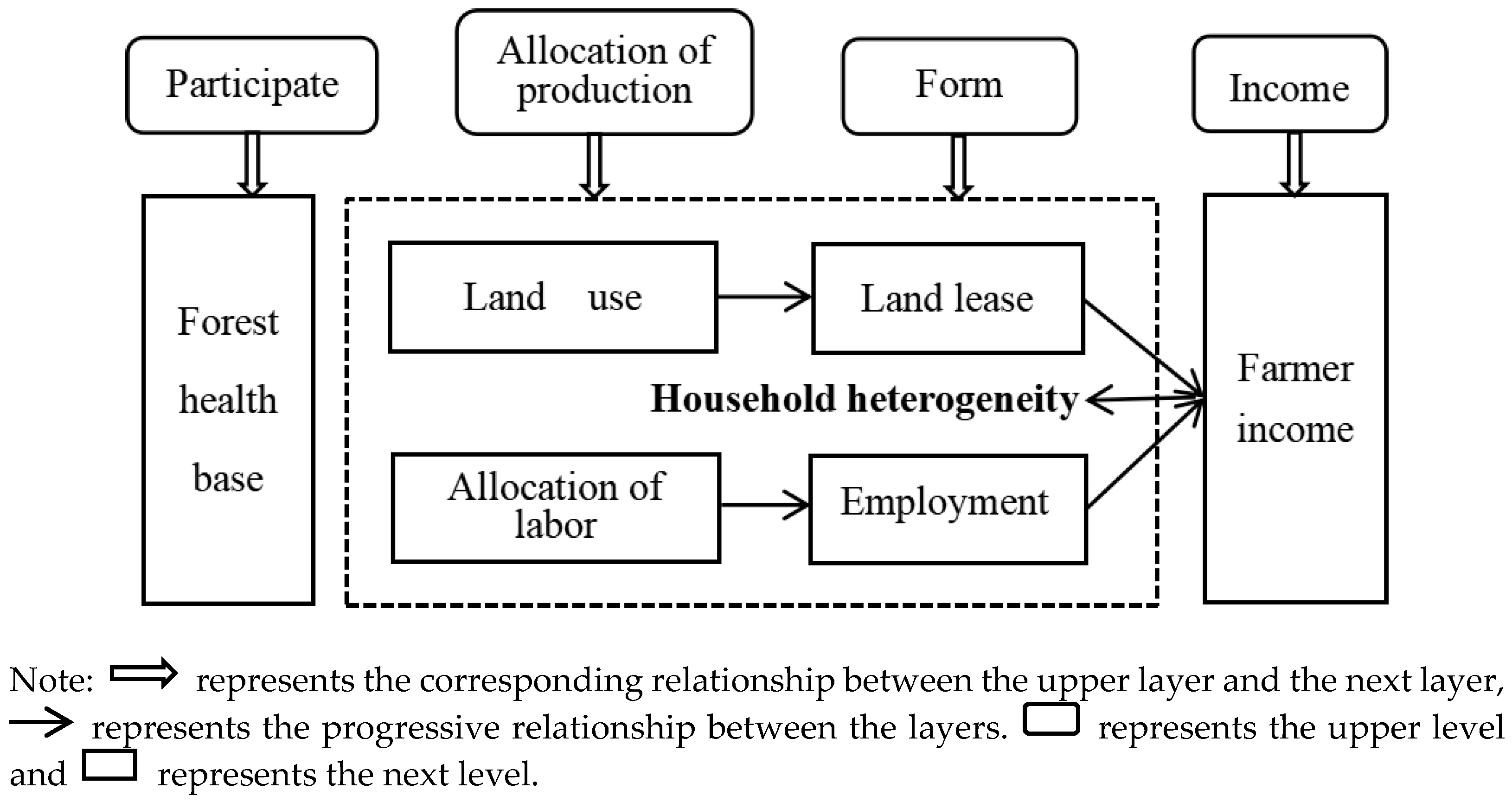

2.1. Impact Mechanism of Sustainable Management of Forest Health Bases on Farmers’ Income

2.1.1. Transformation of Land Use

2.1.2. Reallocation of Labor Resources

2.2. Income Effects of Farmers’ Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Bases

2.3. Impact of Different Forms of Farmers’ Participation

3. Data and Model

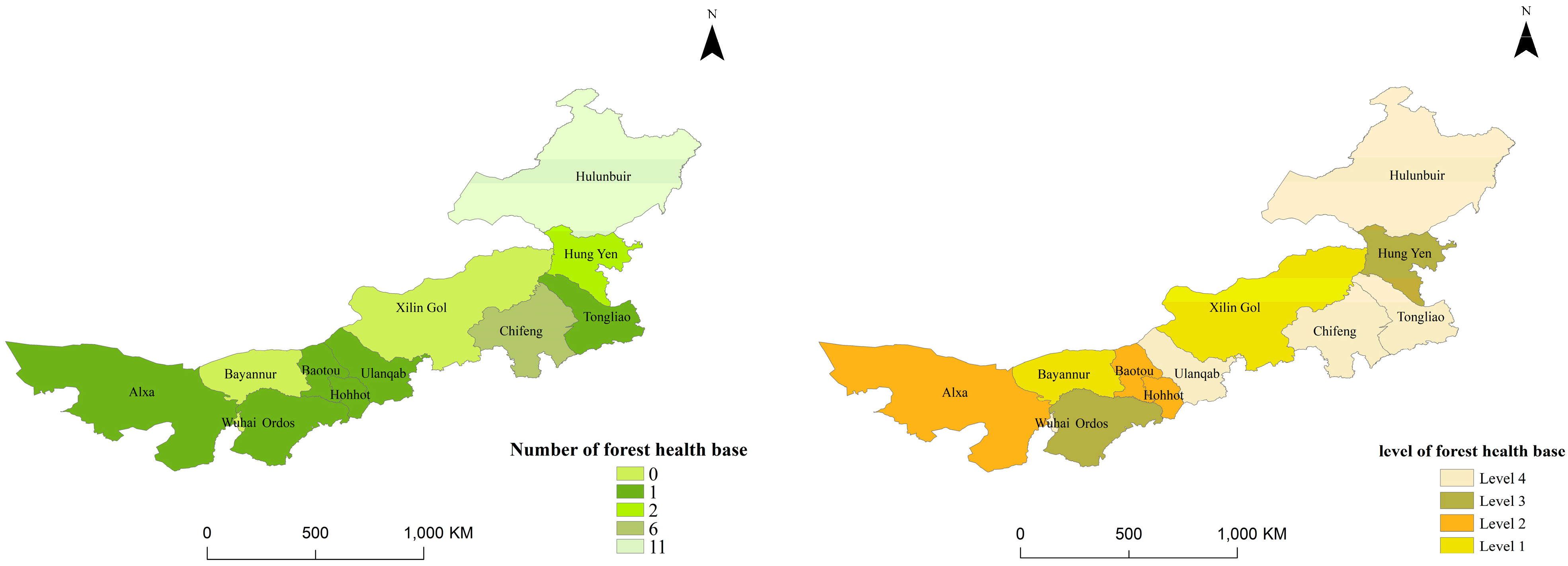

3.1. Data

3.2. Variable Selection and Statistical Analysis

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variables

3.2.3. Identification Variable

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Model

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Factors Influencing Farmers’ Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Bases

4.2. Factors Influencing Annual Household Income

4.3. Average Treatment Effect of Farmers’ Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Bases on Annual Household Income

4.4. Robustness Check

4.4.1. Replacing Estimation Methods

4.4.2. Replacing the Dependent Variable

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Participation Through Employment

4.5.2. Farmer Types

4.5.3. Regional Characteristics

5. Discussions and Suggestions

5.1. Discussions

5.2. Suggestions

6. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forest Health Industry Association. 2023 Research and Analysis Report on the Forest Health Industry; Forest Health Industry Association: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; No. 1 Central Document of 2017. Available online: https://www.crnews.net/zt/zyyhwj/lnzyyhwjhg/440264_20210209124210.html (accessed on 31 December 2016).

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. 2022 Annual Report on Forestry and Grassland; National Forestry and Grassland Administration: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Over 20 Million People Lifted Out of Poverty Through Ecological Poverty Alleviation [EB/OL]. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2020-12/02/content_5566339.htm (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Bussotti, F.; Feducci, M.; Iacopetti, G.; Maggino, F.; Pollastrini, M.; Selvi, F. Linking forest diversity and tree health: Preliminary insights from a large-scale survey in Italy. For. Ecosyst. 2018, 5, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, L.; Di Marzio, P.; Fortini, P. Quercus cerris Leaf Functional Traits to Assess Urban Forest Health Status for Expeditious Analysis in a Mediterranean European Context. Plants 2025, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.T. Research on the development of forest health industry under the background of rural revitalization—A case study of Sanming, Fujian Province. Ind. Innov. Res. 2023, 11, 95–97. [Google Scholar]

- Villacide, J.M.; Gomez, D.F.; Perez, C.A.; Corley, J.C.; Ahumada, R.; Barbosa, L.R.; Furtado, E.L.; González, A.; Ramirez, N.; Balmelli, G.; et al. Forest Health in the Southern Cone of America: State of the Art and Perspectives on Regional Efforts. Forests 2023, 14, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.L. Theoretical Research and Practice of Forest Health. World For. Res. 2016, 29, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Matsunaga, K.N. Forests and Human Health: Recent Trends in Japan. For. Med. Nova Biomed. 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz, J.; Burgas, D.; Potterf, M.; Duflot, R.; Eyvindson, K.; Probst, B.M.; Toraño-Caicoya, A.; Mönkkönen, M.; Gyllin, M.; Grahn, P.; et al. Forests for Health Promotion: Future Developments of Salutogenic Properties in Managed Boreal Forests. Forests 2024, 15, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.T.; Shen, H.D.; Zhang, L.Q.; Yang, L.C.; Mao, A.; Yuan, Y.F. Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation and Forest Health Industry Integrated Development. Am. J. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 4, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Qie, G.F. Cross-Border Integration is the Inevitable Path for the Development of Forest Health. For. Econ. 2017, 39, 3–6+11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.F.; Yu, Y.W.; Xu, M.L.; Zhang, W.F. What is Forest Health? Reflections Based on the Multifunctionality of Forests and the Integration of Related Industries. For. Econ. 2018, 40, 58–60+103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murage, P.; Anton, B.; Chiwanga, F.; Picetti, R.; Njunge, T.; Hassan, S.; Whitmee, S.; Falconer, J.; Waddington, H.S.; Green, R. Impact of tree-based interventions in addressing health and wellbeing outcomes in rural low-income and middle-income settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e157–e168. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, S.; Dincă, I.; Shikha, S. Evaluating local livelihoods, sustainable forest management, and the potential for ecotourism development in Kaimur Wildlife Sanctuary, India. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1491917. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.D. Analysis of the Integrated Development of the Forest Health Industry from the Perspective of Ecological Value Transformation. Shanxi Agric. Econ. 2023, 9, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, D.; Matthias, F. Remote sensing forest health assessment—A comprehensive literature review on a European level. Cent. Eur. For. J. 2025, 71, 14–39. [Google Scholar]

- Safe’i, R.; Rezinda, C.F.G.; Banuwa, I.S.; Harianto, S.P.; Yuwono, S.B.; Rohman, N.A.; Indriani, Y. Factors Affecting Community-Managed Forest Health. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2022, 10, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Choi, S. Environmental influence in the forested area toward human health: Incorporating the ecological environment into art psychotherapy. J. Mt. Sci. 2020, 17, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Xing, H.; Chi, K.; Wang, W.; Song, L.; Xing, X. Orchid diversity and distribution pattern in karst forests in eastern Yunnan Province, China. For. Ecosyst. 2023, 10, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, G.J.; Duan, J.Y.; Liu, J.C. Research on the Dynamic Mechanism of Forest Health Industry Development. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 13, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Problems and Countermeasures for the Development of the Forest Health Industry Under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. China For. Ind. 2023, 228, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L.; Luo, M.; Xu, Y.Y.; Shi, B.J.; Chen, H.B.; Shen, L.X. Research Status of Domestic Forest Health. J. Southwest For. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2022, 6, 105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Shi, C.C. Exploration of Developing the Forest Health Industry Under the Rural Revitalization Strategy: A Case Study of Ankang, Shaanxi. Agric. Technol. Equip. 2020, 368, 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.H. Exploration and Research on the Implementation Path of Forest Health Industry Development Under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. China Constr. 2023, 314, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Pan, K. Research on the Subjectivity of Farmers in the Development of the Forest Health Industry Under the Comprehensive Rural Revitalization Strategy. Rural Econ. 2022, 473, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y. Research on the Impact Path of the Forest Health Industry on the Improvement of Local Farmers’ Well-Being Under the Rural Revitalization Strategy. Economist 2021, 391, 145–146. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, N.A.; Alzuman, A. Effect of per Capita Income, GDP Growth, FDI, Sectoral Composition, and Domestic Credit on Employment Patterns in GCC Countries: GMM and OLS Approaches. Economies 2024, 12, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Qiu, X.; Chen, S. Empirical study on the effects of technology training on the forest-related income of rural poverty-stricken households—Based on the PSM method. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Lu, Y.; Kong, F.B. Effects of Grain for Green Project on the Income of Households at Different Poverty Levels. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2020, 56, 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Zheng, S.F.; Chen, R.J. The Influencing Factors and Income Effects of Green Prevention-Control Technology Adoption: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Survey Data of 792 Vegetable Growers. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.W.; Kwon, G.H.; Moon, S.H. The policy effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit in Korea: Focusing on the analysis of PSM with DID·DDD. Korean Policy Stud. Rev. 2015, 24, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, N.T.; Izumi, I. A Study on the Effectiveness of Agroforestry in Northern Vietnam: The Comparison of Agroforestry, Agriculture and Forestry, and Agricultural Household Group in Terms of Land, Labor, and Income. Proc. Annu. Conf. Agric. Econ. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 2003, 453–458. [Google Scholar]

- Akpo, C.Y.; Pocol, C.B.; Moldovan, M.-G.; Houensou, D.A. Land Access Modes and Agricultural Productivity in Benin. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L. Development Model and Improvement of the Forest Health Industry in State-Owned Forest Farms: A Case Study of Three Forest Farms in the Wuling Mountain Area of Hunan Province. Agric. Technol. 2023, 43, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.K.; Wu, X.J.; Zhao, X.Y. Research on Key Influencing Factors for the High-Quality Development of Forest Health Bases. Issues For. Econ. 2023, 43, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.H.; Wang, X. Research on the Development Countermeasures of the Forest Health Industry Under the Perspective of Beautiful Countryside Construction. Agric. Econ. 2022, 417, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Muhabaiti, P.R.; Xiayidan, A.L.M.; Kailiman, P.E.H.T. An Empirical Study on the Income Effect of Farmers’ Non-Agricultural Employment: Based on a Micro-Survey of Four Prefectures in Southern Xinjiang. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, S.Z.; Fei, E.D.M. Types and Influencing Factors of Forestry-Related Livelihood Activities of Mountain Farmers. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2010, 20, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Xu, K.; Jin, L.S. Research on the Impact of Wetland Ecological Compensation on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies and Income: A Case Study of Survey Data from Poyang Lake Area. China Land Sci. 2021, 35, 72–80+108. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L. Research on the Income Increase of Low-Income Farmers: A Case Study of Kaifeng City. Mod. Agric. Res. 2023, 29, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.L.; Su, J.B.; Ma, J.Z. The Impact of Tourism Development on the Spillover Effect of Landscape Edge Plants. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 3653–3660. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D.; Luo, L.Y.; Yu, Y.; Kong, F.B. The Impact of Forest Resource Cultivation Projects on the Urban-Rural Income Gap in Revolutionary Old Areas. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2023, 59, 74–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.W.; Jiang, J.Y.; Zhang, S.Y. Research on the Livelihood Transformation and Income Effect of Poverty-Alleviated Households: Based on Data from 890 Poverty-Alleviated Households in Q County, Dabie Mountain Area. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 2023, 37, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, R.; Wang, W.L.; Yu, J. The Impact of Endogenous Motivation on Farmers’ Household Income Under the Sustainable Livelihood Framework. J. Northwest. AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 19, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.D.; Bai, X.G. Research on the Income Effect of Farmers’ Participation in E-Commerce: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Endogenous Switching Model. World Agric. 2021, 12, 40–48+127–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y.; Gao, J.Z. Impact of Eco-Efficiency Compensation for Public Welfare Forests on the Incomes of Farmers. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 18, 181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhou, J.; Ren, M.H. Income Effect of Green Production Factor Input Behavior of Agricultural Producers. J. Northwest. AF Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 24, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L.; Wang, X.Q.; Chen, D.Q. Land Transfer and Farmers’ Income Growth: From the Perspective of Income Structure. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.L.; Yuan, X.; Jin, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, D.Q. Does the Adoption of Green Ecological Technology Improve Farmers’ Welfare? Based on a Survey of 654 Banana Growers. Ecol. Econ. 2024, 40, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lokshin, M.; Sajaia, Z. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Endogenous Switching Regression Models. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata 2004, 4, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, C.D.L.; Justo, W.R.; da Silva Filho, L.A. Income Differentials in The Formal Work of Pendular Migrants in the Northeast States: A Quantile Regression Approach. Lect. Econ. 2024, 101, 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z. The Impact of the Digital Economy on the Rural-Urban Income Gap: Moderating Effects Based on the Level of Technology Market Development. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 12, 335–352. [Google Scholar]

| Region | Sample Size | Forms of Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Bases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment (Participation Rate %) | Non-Employment (Participation Rate %) | Land Leasing (Participation Rate %) | Non-Leasing (Participation Rate %) | ||

| Total | 458 | 265 (57.86) | 193 (42.14) | 145 (31.66) | 313 (68.34) |

| Eastern: Hulunbuir | 136 | 37 (27.21) | 99 (72.79) | 57 (41.91) | 79 (58.09) |

| Central: Chifeng | 125 | 109 (87.20) | 16 (12.80) | 23 (18.40) | 102 (81.60) |

| Central: Tongliao | 96 | 60 (62.50) | 36 (37.50) | 30 (31.25) | 66 (68.75) |

| Western: Ulanqab | 101 | 59 (58.42) | 42 (41.58) | 35 (34.65) | 66 (65.35) |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Description | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Annual Household Income | Average annual household income over the past 3 years | 10.9896 | 0.0298 |

| Participation in Forest Health Base | Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Base | Participation in employment: Yes = 1; No = 0 | 0.5786 | 0.0231 |

| Participation in land leasing: Yes = 1; No = 0 | 0.3166 | 0.0218 | ||

| Identification Variable | Distance to Forest Health Base | Distance between the household and the forest health base | 6.4559 | 0.5724 |

| Individual Characteristics | Gender | Male = 1; Female = 2 | 1.4127 | 0.0230 |

| Age | 25 years and below = 1; 26–35 years = 2; 36–45 years = 3; 46–55 years = 4; Over 55 years = 5 | 3.7450 | 0.0492 | |

| Education Level | No schooling = 1; Primary school = 2; Middle school = 3; High school = 4; College and above = 5 | 3.4301 | 0.0508 | |

| Personal Health Status | Very healthy = 1; Healthy = 2; Average = 3; Unhealthy = 4; Very unhealthy = 5 | 2.0459 | 0.0399 | |

| Marital Status | Married = 1; Unmarried = 2; Divorced = 3 | 1.1572 | 0.0226 | |

| Household Characteristics | Family Members’ Health Status | Very low = 1; Low = 2; Average = 3; High = 4; Very high = 5 | 2.1376 | 0.0473 |

| Number of Family Members | Actual number of family members | 3.5633 | 0.0542 | |

| Annual Household Expenditure | Average annual household expenditure over the past 3 years | 10.0770 | 0.0278 | |

| Household Fixed Asset Investment | Actual annual investment in fixed assets | 8.0716 | 0.0352 | |

| Per Capita Arable/Forest Land Area | Total arable or forest land area/number of family members | 4.5253 | 0.1763 | |

| Household Social Relations Status | Very weak = 1; Weak = 2; Average = 3; Strong = 4; Very strong = 5 | 3.3537 | 0.0339 | |

| Type Dummy Variable | Agriculture-oriented | Agriculture-oriented = 1; Others = 0 | 0.3690 | 0.0199 |

| Forestry-dependent | Forestry-dependent = 1; Others = 0 | 0.3668 | 0.0232 | |

| Non-agricultural Non-forestry-oriented | Non-agricultural non-forestry-oriented = 1; Others = 0 | 0.2641 | 0.0229 | |

| Regional Dummy Variable | Hulunbuir | Hulunbuir = 1; Others = 0 | 0.2969 | 0.0214 |

| Tongliao | Tongliao = 1; Others = 0 | 0.2729 | 0.0208 | |

| Chifeng | Chifeng = 1; Others = 0 | 0.2096 | 0.0190 | |

| Ulanqab | Ulanqab = 1; Others = 0 | 0.2205 | 0.0194 |

| Variable | Participating Households | Non-Participating Households | Mean Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Mean | Standard Deviation | |||

| Employment | Average household annual income | 10.8903 | 0.0328 | 10.8405 | 0.0388 | 0.0498 |

| Land Leasing | 10.8796 | 0.0313 | 10.8471 | 0.0416 | 0.0325 | |

| Variables | Model 1 (Employment, n = 458) | Model 2 (Land Leasing, n = 458) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision Equation | Result Equation | Decision Equation | Result Equation | |||

| Participation | Non-Participation | Participation | Non-Participation | |||

| Gender | 0.4924 *** (0.1673) | −0.2112 *** (0.0489) | 0.0948 (0.0717) | 0.0279 (0.0672) | −0.0148 (0.0653) | −0.0818 (0.0553) |

| Age | −0.1715 * (0.0942) | 0.0596 * (0.0285) | −0.1046 ** (0.0424) | 0.0586 (0.1319) | 0.0235 (0.0371) | 0.0185 (0.0326) |

| Education Level | −0.4782 *** (0.0917) | 0.1381 *** (0.0310) | −0.0250 (0.0426) | 0.0175 (0.0189) | 0.0379 (0.0370) | 0.0541 * (0.0310) |

| Personal Health Status | −0.2175 ** (0.1097) | 0.1383 *** (0.0477) | −0.0471 (0.0526) | −0.1586 (0.1249) | 0.0294 (0.0409) | −0.0127 (0.0378) |

| Marital Status | −0.0067 (0.1753) | 0.0126 (0.0330) | 0.0354 (0.0819) | −0.0681 (0.0709) | 0.0655 (0.0686) | −0.0175 (0.0584) |

| Family Members’ Health Status | −0.2284 *** (0.0742) | 0.0005 (0.0216) | −0.2287 *** (0.0518) | −0.0015 (0.0586) | −0.0231 (0.0264) | −0.0269 (0.0288) |

| Number of Family Members | 0.6081 ** (0.2749) | 0.1837 ** (0.0747) | 0.1016 (0.1263) | 0.0264 (0.2005) | 0.0042 (0.0977) | 0.0010 (0.0865) |

| Annual Household Expenditure | 0.3617 ** (0.1578) | 0.3406 *** (0.0499) | 0.6632 *** (0.0739) | 0.0388 *** (0.0836) | 0.0949 (0.0772) | 0.3699 *** (0.0553) |

| Household Fixed Asset Investment | 0.1869 * (0.1111) | 0.0511 * (0.0340) | 0.2346 *** (0.0487) | 0.3621 (0.1359) | 0.1025 ** (0.0432) | 0.0535 (0.0382) |

| Per Capita Arable/Forest Land Area | 0.08504 *** (0.0231) | 0.0308 *** (0.0075) | 0.0297 *** (0.0113) | 0.0872 (0.0873) | 0.0092 (0.0072) | 0.0114 (0.0087) |

| Household Social Relations Status | −0.0112 (0.1174) | −0.0090 (0.0340) | −0.2079 *** (0.0555) | −0.0197 (0.0918) | −0.0864 (0.0443) | −0.0659 * (0.0399) |

| Agriculture-oriented | −1.305 *** (0.2804) | 0.0803 (0.0674) | 0.1239 (0.1445) | 0.2130 (0.1993) | 0.1061 (0.0935) | 0.3055 *** (0.0842) |

| Forestry-dependent | −1.6304 *** (0.2931) | 0.2517 *** (0.0888) | 0.0058 (0.1529) | −0.6043 *** (0.1973) | −0.0693 (0.1041) | 0.3499 *** (0.0984) |

| Hulunbuir | −1.0090 *** (0.2635) | 0.0358 (0.0973) | −0.2305 ** (0.1123) | −0.3044 (0.2058) | 0.1613 * (0.0988) | −0.1488 (0.0996) |

| Chifeng | 0.3800 (0.2497) | −0.2399 *** (0.0684) | 0.1505 (0.1310) | −0.3424 *** (0.2283) | −0.1734 (0.1140) | −0.0689 (0.0882) |

| Ulanqab | −0.7915 *** (0.2559) | −0.0609 (0.0767) | −0.5335 *** (0.1163) | 0.2130 (0.1993) | −0.0114 (0.0948) | −0.1628 *** (0.0921) |

| Distance to Forest Health Base | 0.2256 *** (0.0694) | - | - | 0.0913 *** (0.0357) | - | - |

| Constant | −2.1658 (2.0724) | 6.4199 *** (0.6380) | 4.1558 *** (0.8804) | −4.352 *** (1.6312) | 9.3166 *** (1.0072) | 6.8004 *** (0.7018) |

| lns1 | - | −0.8251 *** (0.0805) | - | - | −0.6942 *** (0.0451) | - |

| r1 | - | 0.8187 *** (0.2800) | - | - | 2.7632 *** (0.2781) | - |

| lns0 | - | - | −1.0490 *** (0.0519) | - | −1.1413 (0.1016) | |

| r0 | - | - | −0.4792 *** (0.1863) | - | 0.3027 *** (0.4100) | |

| Log likelihood | −364.5146 | −397.1396 | ||||

| Wald chi2 | 319.9700 *** | 28.1700 *** | ||||

| Engagement | Treatment Effect | Change Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation | Non-Participation | ATT | ATU | |||

| Employment | Participating Households | 11.6030 | 11.0853 | 0.5177 *** | - | 4.28% |

| Non-participating Households | 11.6033 | 10.8564 | - | 0.7469 *** | 5.87% | |

| Land Leasing | Participating Households | 11.2599 | 11.0632 | 0.1967 *** | - | 1.44% |

| Non-participating Households | 11.4852 | 10.6483 | - | 0.8369 *** | 2.55% | |

| Method | ESRM | PSM | OLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment | ATT | 0.5177 *** | 0.1955 *** | - |

| ATU | 0.7469 *** | 0.0058 *** | - | |

| Coefficient | - | - | 0.2641 *** | |

| Land Leasing | ATT | 0.1967 *** | 0.5584 *** | - |

| ATU | 0.8369 *** | 0.5402 *** | - | |

| Coefficient | - | - | 0.5552 *** | |

| Engagement | Treatment Effect | Change Rate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation | Non-Participation | ATT | ATU | |||

| Employment | Participating Households | 9.8456 | 8.7234 | 1.1221 *** | - | 2.55% |

| Non-participating Households | 9.6935 | 8.6135 | - | 1.0800 *** | 2.82% | |

| Land Leasing | Participating Households | 9.6638 | 7.5726 | 2.0911 *** | - | 3.46% |

| Non-participating Households | 9.6642 | 8.2352 | - | 1.4290 *** | 2.08% | |

| QR_10 | QR_25 | QR_50 | QR_75 | QR_90 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participation Behavior | Employment | 0.4170 *** (0.0724) | 0.3070 *** (0.0554) | 0.2110 ** (0.0583) | 0.1300 ** (0.0625) | 0.0293 (0.0733) |

| Land Leasing | 0.4380 *** (0.0955) | 0.3680 *** (0.0598) | 0.4530 *** (0.0474) | 0.5880 *** (0.0274) | 0.6340 *** (0.0322) | |

| Farmer Types | Agriculture-oriented Type | 0.1570 (0.1530) | 0.0961 (0.1170) | 0.0770 (0.1230) | -0.0779 (0.1320) | -0.2410 (0.1550) |

| Forestry-dependent Type | 0.3250 ** (0.1560) | 0.2400 ** (0.1200) | 0.1240 (0.1260) | -0.0708 (0.1350) | -0.2640 * (0.1580) | |

| Non-agriculture Non-forestry-oriented Type | −0.0274 (0.1200) | −0.1110 (0.0920) | −0.0825 (0.0967) | −0.1720 * (0.1040) | −0.2380 * (0.1220) | |

| Regional Characteristics | Hulunbuir | −0.0798 (0.1030) | −0.1070 (0.0789) | −0.1100 (0.0829) | −0.1290 (0.0888) | −0.0364 (0.1040) |

| Chifeng | −0.1330 (0.0912) | −0.1390 ** (0.0699) | −0.2190 *** (0.0735) | −0.2750 *** (0.0787) | −0.2260 ** (0.0923) | |

| Ulanqab | −0.0798 (0.0942) | −0.1510 ** (0.0722) | −0.1220 (0.0759) | −0.1290 (0.0813) | −0.0427 (0.0954) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, H.; Bao, Q.; Arshad, M.U.; Lin, H. Assessing Income Heterogeneity from Farmer Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Initiatives. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072894

Lin H, Bao Q, Arshad MU, Lin H. Assessing Income Heterogeneity from Farmer Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Initiatives. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072894

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Haihua, Qingfeng Bao, Muhammad Umer Arshad, and Haiying Lin. 2025. "Assessing Income Heterogeneity from Farmer Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Initiatives" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072894

APA StyleLin, H., Bao, Q., Arshad, M. U., & Lin, H. (2025). Assessing Income Heterogeneity from Farmer Participation in Sustainable Management of Forest Health Initiatives. Sustainability, 17(7), 2894. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072894