Abstract

There is a global demand for alternative energy sources away from unsustainable fossil fuels. The Conference of Parties (COP) 26 agreed that fossil fuels should be phased down; at COP27, anxiety about the cost and availability of energy was raised, and COP28 reiterated the phasedown of coal power. Solar technology in the form of perovskite solar cells is one such alternative energy source. This article considers the fabrication of the perovskite layer in a solar cell and postulates the extent to which material flow cost accounting (MFCA) could be used as a feasible costing method, among other things, to address material flows and waste reduction. Through MFCA, the monetary and physical flows of materials are identified and can be applied throughout the supply chain to facilitate affordability, from the extraction of the ore to the transportation and fabrication of the chemicals, manufacturing and distribution of the solar cell and panels, and, finally, the recycling of the panel. Informed by these observations, a conceptual framework for applying MFCA in fabricating the perovskite layer in the supply chain is developed based on sets of qualitative propositions. Future work will involve researching the processes involved in manufacturing solar cells, costing raw materials, energy flows, and solar cell manufacturing emissions.

1. Introduction

More than 55% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and 40% of health-related impacts are caused by the extraction and processing of natural resources such as fossil fuels and minerals. One of the main applications of fossil fuels is the production of energy, and, in this process, the demand for fossil fuels equals 65% of the total material demand, with the highest material footprint (72%) in high-income countries [1]. Furthermore, the United Nations (UN) indicated that the GHGs that act as a blanket that covers the Earth and traps the sun’s heat are the result of energy and heat generated by fossil fuels [2]. To keep track of emissions from all countries, the Conference of Parties (COP) was formed in 1995 [3]. This was followed by the development of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 to reduce poverty and hunger, and most of the effects of climate change. Two (2) of these SDGs form the basis for this research, namely ‘Affordable and clean energy’ (SDG #7) and ‘Climate action’ (SDG #13) [4]. Ref. [5] confirmed the importance of using renewable energy to achieve the SDGs when they established how significantly climate change promotes the use of renewable energy. A link between poverty, the SDGs, and renewable energy is made by [6], indicating that only a third of the people from Sub-Saharan Africa have electricity, and they argue that solar home systems might assist with supplying electricity to rural areas.

Ref. [2] identified five (5) reasons why the transition to clean energy should be accelerated. Renewable sources that surround us are less expensive, healthier, create jobs, and make economic sense. Furthermore, renewable energy is becoming increasingly important in the global economy [7]. One of these renewable energy sources is solar, which includes photovoltaics or solar cell technology. Solar cell technology may be divided into three generations [8]. The first generation is the crystalline silicon (c-Si) or multi-crystalline silicon solar cells [9]. These are most commonly employed commercially because of their high efficiency, low toxicity, and ruggedness. However, this generation of solar technology is quite expensive and has a long energy payback time. The second-generation solar technology is mainly based on cells containing cadmium-telluride (CdTe), copper-indium-gallium-selenide (CIGS) or amorphous silicon (a-Si:H) [10]. These cells are cheaper to produce than the first-generation solar cells, though they are less efficient than their former generation. Finally, the third-generation solar cell technology focuses on newly developed or experimental technologies. The main focus here is given to dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) and perovskite solar cells (PSCs) [11]. In 2023, the worldwide PSC market size was valued at USD 64.05 million. The growth of this market is projected from USD 105.23 million in 2024 to USD 1760.59 million by 2032 [12]. This illustrates the importance of PSCs.

Despite the above advances, ref. [9] predicted that a solar farm of 160,000 km2 in the Sahara Desert is needed to serve the energy needs worldwide, which, with present technologies, may not be economically feasible. The main aim of most companies is to generate a profit; therefore, saving on costs and waste would provide a better bottom line. It stands to reason that initiatives regarding the search for affordable and clean energy (SDG #7) would involve investigating feasible costing methods. Ref. [13] considers the design and cost analysis of a perovskite solar panel manufacturing process, allowing for the material and equipment costs associated with perovskite PV production to be estimated in different geographical locations, while [14] presents a techno-economic analysis of a carbon-based perovskite solar module (CPSM) factory located in India using a bottom-up approach.

An alternative costing method is material flow cost accounting (MFCA), which analyzes the flow of materials when manufacturing a product [15]. MFCA further traces waste, emissions and non-products leading to better economic and environmental performance of the company [15]. However, an initial capital layout might be needed to implement MFCA, and the relevant companies may need to ensure the return on investment (ROI) before embarking on such an initiative. MFCA is one of the practices of environmental management accounting (EMA), which includes energy accounting (EA), water-management accounting (WMA), the sustainable balanced scorecard (SBSC), and carbon management accounting (CMA) [16]. These EMA practices are not mutually exclusive; for example, MFCA is used with material and waste accounting, WMA, and CMA. Owing to its widespread application, this article focuses on using MFCA for perovskite costing.

Our work is multidisciplinary, and the novelty of this article lies in the way in which we build a bridge between the scientific field of perovskite solar technology and MFCA. Specifically, we formulate a conceptual framework to cost the fabrication of PSCs. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this work is the first of its kind in using MFCA to cost PSCs. The authors declare that part of this work was recently published as a peer-reviewed conference paper [17].

The layout of the rest of the article is as follows: Following Section Research Questions and Objective, the research methods for the article are discussed in Section 2. Amongst other things, Section 2 justifies the use of Saunders et al.’s research onion [18] in our work and states the delimitations of our research. A literature review on perovskite solar cells and material flow cost accounting is presented in Section 3 as a precursor to our findings in Section 4, which considers the fabrication of the perovskite layer in the perovskite solar cell (PSC), mining the ore, transporting the chemicals and products, the recycling of a solar panel, and material flow cost accounting as a plausible costing method in the fabrication of a PSC. A sub-framework and a PSC-MFCA framework embedding the sub-framework are given in Section 4. This is followed by Section 5 with a discussion of the framework, followed by a case study in Section 6 to illustrate the utility of our framework. A conclusion considering the theoretical and practical contributions of this work, possible limitations, and directions for future work in this area is given in Section 7.

Research Questions and Objective

This article aims to identify the processes needed to manufacture and suggest a possible costing method for the perovskite layer in a solar cell by developing a conceptual framework using qualitative propositions. The motivation for this article hinges on the need for affordable and clean energy and climate action per sustainable development goals #7 and #13. Consequently, the following research questions (RQ) are stated:

- RQ1: Which chemicals are needed to fabricate a perovskite layer in a solar cell?

- RQ2: To what extent may material flow cost accounting (MFCA) be a suitable costing method for fabricating the perovskite solar cell layer throughout the supply chain?

Our objective is to:

- RO: Develop a conceptual framework for perovskite solar cell costing through MFCA.

2. Materials and Methods

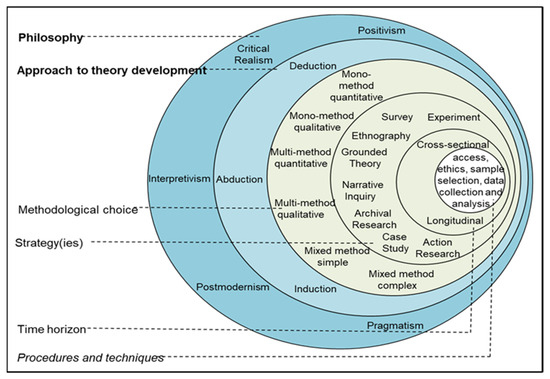

Our methodology in this article follows the layout of the generic Saunders et al. research onion [18], depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Saunders et al.’s research onion. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [18]. 2024, M.N.K. Saunders.

Starting at the outer layer of the onion, our research philosophy may be described as a mix of positivism and interpretivism. It is positivist since we are working with precise chemical equations later in this article, and the interpretivism stems from the conceptual frameworks we develop in this work.

In doing so, we adopt a combination of three types of conceptual approaches as described by Jaakkola [19]: Theory synthesis, in that we combine two theories or areas, namely, MFCA and perovskite solar technology; model building, which constructs a conceptual framework, which amongst other things, predicts associations among constructs, as a step towards costing PSC technology through MFCA; and, to a lesser extent, theory adaptation, in that the use of MFCA in costing perovskite technology is relatively sparse. In all these, we apply our theory of qualitative propositions developed in earlier work [20]. Ref. [21] argues that a conceptual framework links concepts through a network to understand a phenomenon. The advantages of a conceptual framework are flexibility, capacity for modification and understanding. The concepts are flexible, unlike rigid theoretical variables and causal relationships (owing to the dynamic nature of our framework later in this article). Conceptual frameworks can be modified as new research comes to the fore and are evolutionary rather than static. A conceptual framework aims to understand the phenomena, not predict them. An interpretive approach to social reality is provided with a conceptual framework rather than a causal/analytical setting and is developed and constructed using qualitative analysis [21].

Our approach to theory development at the second layer from the outside is a mix of induction and pseudo-deduction. It is inductive since we build a conceptual framework, and the pseudo-deductive character stems from us subsequently reasoning about the utility of the framework and the propositions we develop in this article.

The methodological choice at the third layer is essentially qualitative since we utilize qualitative propositions to develop a conceptual framework in the form of a diagram. Our strategy at layer four is a survey in the form of a literature review and a case study as a hypothetical case that we formulate in Section 6 as part of our pseudo-deduction, serving as a validation of our framework. Our time horizon is cross-sectional since this work is done within a shorter period than longitudinal research spanning a long time, e.g., research in social science. Our procedures and techniques at the innermost layer embody a literature review and conceptual framework development through analyzing chemical formulae and developing propositions. Future work at the innermost layer will involve case studies in the perovskite industry and quantitative analyses where we perform specific measurements regarding PSC cost, waste generation, and degradation. We return to these in the section on future work.

In utilizing the research onion in Figure 1, we provide a critical account of the processes and materials involved in fabricating the perovskite layer in a solar cell in the first part of this work. In the second part, we argue that material flow cost accounting (MFCA) may be a relevant costing method. A PSC-MFCA framework is developed through three (3) sets of qualitative propositions to facilitate affordable and clean energy through perovskite solar technology, in line with achieving SDGs #7 and #13. The researchers analyzed the fabrication of a specific layer in a perovskite solar cell to argue the case for using MFCA in costing a solar panel. Naturally, the cost of any product plays an important role in the final capital layout of the buyer. The research analyzed scholarly literature from chemistry and management accounting.

2.1. The Use of Propositions

The propositions utilized in this work are of the following three (3) kinds [20]:

- Content propositions, denoted by Cpi, for i ∈; {1, 2, 3, …}. Content propositions identify elements (content) of entities, which are the building blocks in the framework.

- Association propositions, denoted by Apj, for j ∈ {1, 2, 3, …}. Association propositions define associations among the building blocks of the framework.

- Consequential propositions indicated by Cons_pk, for k ∈ {1, 2, 3, …}. Consequential propositions capture information of the following form: if p then q.

Occasionally, intermediate forms of our propositions are suffixed with an alphabetic character after the proposition number to indicate that a proposition is enhanced through deeper analyses of the literature. Once a final version of a proposition is obtained, the alphabetic character is dropped. The formulation of propositions in the rest of this article illustrates this technique.

2.2. Delimitations

This article assumes the perovskite solar cell as the research unit and will not evaluate or debate the merits of the more technical aspects of Si-solar cells or organic SC [22] compared with perovskite solar cells. Neither does it aim to be a quantitative physical sciences paper on PSCs, their production, synthesis, or physical properties. Rather, it is a qualitative discussion of how PSCs can be used as a model to apply material flow cost accounting. Such comparisons are deemed beyond the scope of this work.

3. Literature Review

The global demand for fossil fuels for energy is unsustainable; hence, at COP26 [23], nations agreed that the use of fossil fuels should be phased down. COP27 [24] followed, during which the cost and availability of energy were raised as concerns, and COP28 [25] reiterated that coal power should phase down. Between 1970 and 2020, the use of fossil fuels increased from 6.1 to 15.4 billion tons, while their global extraction decreased from 20% to 16%. While coal’s growth rate grew by 2.1%, natural gas grew by 2.8% and petroleum by 1.3% due to the expansion of coal and gas power plants to generate electricity. Lower gas prices increased renewable energy sources, and improved energy efficacy contributed to a decrease in global coal consumption [26]. However, in 2022, the demand for coal again reached a record high, rising by 4% [27]. Hence, energy alternatives should be identified in order to sustain the world’s increasing energy demands. One such alternative is solar cell technology, and, as indicated in our delimitations in Section 2.2, considering alternatives, for example, Si-SC or organic SC [22], is beyond the scope of this work (refer to Section 2.2).

The above discussions lead to our first content proposition, as follows:

- Proposition Cp1: Worldwide dependence on fossil fuels should be reduced in favor of renewable energy sources, such as solar cell technology.

- ➢

- The consumption of coal simulates a Gartner–Hype CycleTM since its global demand appears to have increased over the decades, decreased for a while, and then increased again.

There are three (3) generations of solar cell technology [8]. Ref. [9] indicates that the first generation is the crystalline silicon (c-Si) or multi-crystalline silicon solar cells. Despite their high efficiency, low toxicity, and ruggedness—resulting in them being the most used commercially—their drawbacks are their expensiveness and long energy payback time (EPBT). According to [10], second-generation solar technology uses cells containing cadmium-telluride (CdTe), copper-indium-gallium-selenide (CIGS), or amorphous silicon (a-Si:H). These cells are less efficient than first-generation cells but less costly to produce. Ref. [9] argues that solar technology focuses on newly developed or experimental technologies (dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs)) and perovskite solar cells (PSCs) and is called the third generation. Ref. [7] argues that perovskites might transform PV, while [28] indicates the fourth generation as inorganic nanostructures (metal oxides and metal nanoparticles) or organic-based nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes and graphene derivatives) with low flexibility or cost. In line with our delimitations in Section 2.2, we focus in this article on the third generation, specifically the perovskite layer.

During 2006 and 2009, laboratory research was conducted to develop a PSC device using perovskites in solar cell technology [29,30]. PSCs attracted much interest owing to their ability to compete with the efficiency of first-generation solar technology. These PSCs have benefits, such as lower manufacturing costs and the ability to function in the shade; therefore, they are more flexible [9]. Additionally, ref. [31] argued that PSCs perform better than dye-sensitized and quantum dot solar cells. That said, further comparison of these is beyond the scope of this work.

The above PSC discussion, in conjunction with our delimitations, leads to a preliminary version of our next content proposition, as follows:

- Proposition Cp2a: Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) may be the technology of choice in embarking on solar cell technology.

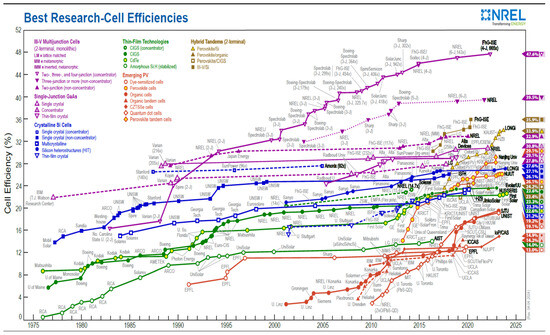

According to [32], the materials to fabricate perovskite solar cells are relatively inexpensive, and the processes are simple. They furthermore report that the efficiencies of these devices increased over the years, from 3.8% to 20.1%; hence, this technology can be the fastest-growing solar cell. This is supported by Figure 2, presenting that perovskite solar technology has grown in a shorter time to nearly the same efficiencies as silicon-based solar technology, first-generation solar cells [33]. This observation supports proposition Cp2a (and later proposition Cp2).

Figure 2.

The official chart of the maximum power conversion efficiencies of all reported solar cell technologies from 1976 to 2023 by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory focuses on emerging third-generation solar technology. Reproduced with permission [33]. Copyright 2024, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, USA.

With an energy payback time (EPBT) of a few months, ref. [34] distinguishes perovskite materials from crystalline silicon solar panels with an EPBT of 1.5 to 4.4 years [35]. Due to the perovskite material’s simple manufacturing processes, at lower temperatures than the standard in the first and second generation of solar technology, they are paving the way for the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) [36] and the 6IR in the context of nanotechnology [37]. However, several other processes must be considered while manufacturing perovskite solar cells. These include the mining of ores, the production of reagent species, the equipment costs such as depreciation and maintenance, and, finally, the manufacturing of the device, which may need to be systematically explored and considered in identifying a suitable costing practice.

The above aspects of the manufacturing of PSCs enhance an earlier proposition into its final formulation, as follows:

- Proposition Cp2: In embarking on solar cell technology, perovskite solar cells (PSCs) may be the technology of choice based on the following advantages and disadvantages:

- ➢

- PSCs inhibit relatively simple manufacturing processes at lower temperatures.

- ➢

- Their manufacturing resides with Industry 4.0 technologies and exhibits aspects of the 6IR regarding renewable energy [37] and nanotechnology.

- ➢

- Their manufacturing supply chain involves mining raw materials, producing reagent species, equipment costs, and manufacturing devices.

The costing aspects of PSCs, mentioned above, lead to the following when serving a worldwide demand:

- Proposition Cp3: Should a worldwide demand for PSCs emerge, suitable costing methods should be devised and employed to make their manufacturing economically feasible.

In this article, we suggest using MFCA as a costing and waste reduction mechanism for cleaner energy in response to proposition Cp3.

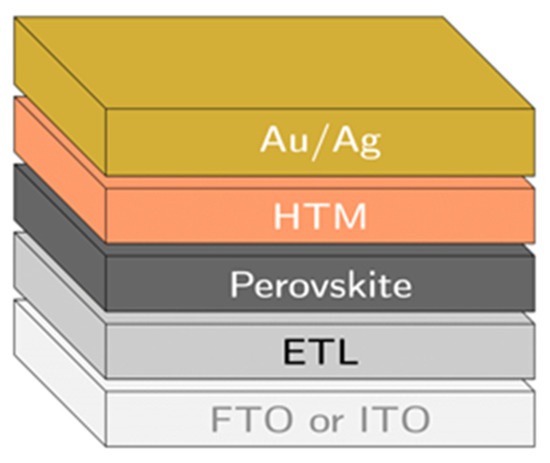

Figure 3 shows several layers of a typical perovskite solar cell (a device). These layers include a layer of fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) or indium-doped tin oxide (ITO), an electron transporting layer (ETL), a perovskite layer, a hole transporting layer (HTL), and an electrode contact (typically gold). These layers are deposited on top of each other to build the device.

Figure 3.

The typical architecture of a planar n-i-p perovskite solar cell (constructed by researchers).

During the manufacturing process, the layers are deposited individually. As indicated in our delimitations, this research focused on the production of the perovskite layer, specifically that of a methyl ammonium lead tri-iodide perovskite (MAPbI3 or CH3NH3PbI3). Therefore, the findings considered the production of all chemicals used in the synthesis and deposition of this perovskite layer, as well as cost considerations in manufacturing a PSC cell, in a further response to the above propositions, Cp2 and Cp3.

Importantly, the most promising single junction PSC cells currently utilize composite active layers that consist of mixtures of several cations and halides. For example, Cs0.05(FA0.77MA0.23)0.95Pb(I0.77Br0.23)3 is the active layer in the PSC with the highest certified power conversion efficiency of 26.1%, as deemed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory [33,38]. To retain focus, this work will develop a framework for utilizing MFCA in the production of PSCs, using MAPbI3 as a basic example, and will seek to serve as a guide on how to apply the same methodology to the fabrication of any PSC.

4. Findings

In the following sub-sections, the fabrication of the perovskite layer in the PSC is detailed, followed by a discussion of MFCA as a possible costing method that could decrease waste, leading to cleaner energy.

4.1. Fabrication of the Perovskite Layer in the PSC

Several fabrication techniques may be employed in the manufacturing of PSCs. However, because of how easily the complexity of the study scales, only the so-called one-step [30] and two-step [39] spin coating methods for a typical perovskite material, methylammonium lead iodide (CH3NH3PbI3(s), MAPbI3), will be considered. These methods require the same instrumentation, a spray coater, and a heat source. In the one-step method, the precursor mixture of lead iodide (PbI2) and methylammonium halides (CH3NH3I) is dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF, C2H7ON) and deposited onto the film to form the perovskite layer. PbI2 is first dissolved in DMF in the two-step method and deposited solely. Subsequently, CH3NH3I is dissolved in isopropyl alcohol (IPA, C3H8O) and deposited [30,39,40]. After the deposition(s) are complete, the film is annealed at 80 °C for 15 min. Naturally, the one-step and two-step processes may incur different costs and wastes.

Regarding the coating methods, spin coating, as indicated in Section 4.6, results in up to 90% waste. Other coating methods, e.g., dip coating, blade coating [41] scrap coating, and slit coating, to name but a few [42], may result in the loss of 10% of the raw materials. That said, spin coating is mentioned in the remainder of this article, owing to its popularity [42]. As indicated in our delimitations, discussing the technicalities and merits of these techniques is beyond the scope of this article. One production model was chosen, and other methods are typically used, as mentioned in the literature [27,35].

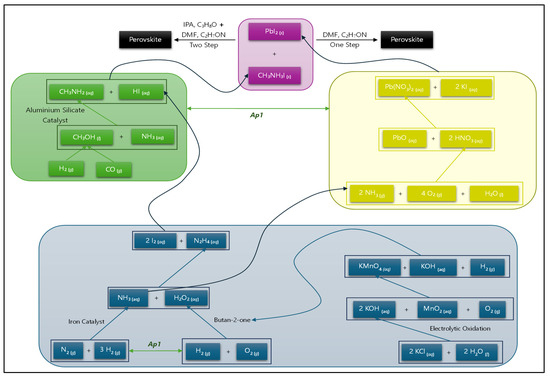

A summary of the main materials involved in the fabrication of the perovskite layer is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Summary of chemicals involved in the fabrication of the perovskite layer (constructed by researchers).

The processes in Figure 4 are indicated from the bottom up, resulting in the top material, the perovskite, MAPbI3. To enhance clarity, not all chemicals and waste products are included. We note some branches of the chemical process which can be conducted in parallel. This observation leads to our first association proposition, as follows:

- Proposition Ap1: The fabrication of a PSC involves two or more groups of processes that may be executed in parallel.

- ➢

- Parallel execution may incur cost savings in placing a product on the market but may necessitate two or more sets of personnel to oversee each process.

Proposition Ap1 informs two sets of parallel processes, as indicated in Figure 4—from the bottom up, we have two parallel processes indicated by proposition Ap1 as a green double arrow and another set of parallel processes higher up between the green and yellow groups, also indicated by Ap1.

Next, we analyze the individual processes in Figure 4 to produce MAPbI3. As shown in Equation (1), acidification of the neutral amine is required. All equations are summarized in Appendix A.

CH3NH2 (aq) + HI (aq) → CH3NH3I (s)

As indicated in Figure 4, water (H2O) is used as a solvent because the reaction is completed in aqueous conditions. The chemicals required for the one-step method include CH3NH2, HI, H2O, PbI2, and C2H7ON, and for the two-step method, all those included for the one-step method, with the addition of C3H8O, leading to a proposition on cost saving:

- Proposition Cp4: The one-step method for fabricating PSCs may be preferred since the compound C3H8O is not needed, leading to reduced costs.

Based on proposition Cp4, the specific chemicals and processes must be further investigated for their origins, individual costing, and waste management.

Production of the Chemicals

This section explores the production of each of the seven (7) chemicals used in the one- or two-step method described earlier. The production of each chemical is to be traced back to the origin of the naturally obtainable components. For each chemical reaction below, an observation is made about possible costing considerations.

Distilled water (H2O): Steam distillation or filtration of any water source is necessary [43] for purification before being ready for use.

Hydrogen Iodide (HI): the reaction between iodine (I2) and hydrazine (N2H4), as per Equation (2) [44], occurs in industrial production, i.e., manufacturing.

2 I2 (aq) + N2H4 (aq) → 4 HI (aq) + N2 (g)

Nitrogen gas is produced as a byproduct.

- Iodine (I2) is sourced from natural brines or caliche ore deposits [45,46]. Iodine from brines can be purified immediately; however, iodine from an ore deposit is first leached through water and further purified.We make the following observation:

- ❖

- Observation #1: Regarding reaction (2):

- ➢

- Several activities, stakeholders, and costs are involved. The costs are mining ore, e.g., iodine; transporting raw materials to the factory or laboratory; and fabricating the relevant materials. The wages and salaries of the mine personnel add to the cost of the reaction.

- ➢

- Waste products, e.g., acid mine drainage (AMD), result from the mining operations [47,48].

- Hydrazine (N2H4): In the industrial production of hydrazine, the peroxide process uses a combination of ammonia (NH3) with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in the presence of a ketone catalyst (butane-2-one) to form hydrazine [49]. Equation (3) shows that water is produced as a byproduct and that ammonia, hydrogen peroxide, and butane-2-one should be produced for this synthesis to be viable.

- ❖

- Observation #2: Augmenting observation #1:

- ➢

- Several activities, stakeholders, and costs are involved. The costs are mining ore, e.g., iodine; transporting raw materials to the factory or laboratory; and fabricating the relevant materials.

- ➢

- The transport costs involved in moving the product from the factory to the laboratory, operational costs, and the remuneration of the personnel involved add to the cost of the product.

- ➢

- Waste products, e.g., acid mine drainage (AMD), result from the mining operations [47,48]. The formation of N2H4 occurs in a factory, compounding industrial waste and greenhouse gases [16].

As per Figure 4, reaction (3) occurs next:

- Ammonia: the Haber–Bosch process [50] is almost exclusively used in the industrial production of ammonia. Equation (4) gives the Haber–Bosch process.

Nitrogen gas, hydrogen gas, and iron are required for the production of ammonia.

- Nitrogen gas (N2): By purifying air, which contains 78% nitrogen [44], nitrogen is obtained on an industrial scale. We observe the following:

- ❖

- Observation #3: The cost of reaction (4), regarding forming nitrogen gas, stems from manufacturing or fabrication costs.

- Hydrogen gas (H2): This is produced from the steam reforming of natural gas, coal gasification, or the partial oxidation of other hydrocarbons [51]. A similar observation as in observation #3 may be made for nitrogen gas formation.

- An Iron catalyst is used in the form of magnetite (Fe3O4) from iron ores [52]. Observations #1, #2, and #3 also hold here, due to the underlying mining and manufacturing processes.

- Hydrogen peroxide: Produced by the anthraquinone process using an anthraquinone derivative and palladium (a catalyst) through a hydrogenation reaction in the presence of oxygen. This process is shown in Equation (5).

- Oxygen gas is distilled from the air in oxygen plants [53]. Consequently, this process is relatively inexpensive.

- Anthraquinone derivative: Anthraquinone is synthesized by acid catalysis of styrene [54]. Styrene can be obtained from the dehydrogenation of ethylbenzene over an iron oxide catalyst, which is obtained from the refining of crude oil [55]. This process may be costly; hence, observations #1, #2, and #3 hold.

- Palladium (Pd) is obtained from cooperite and polarite minerals. The usual mining and related processes apply here, leading to observations #1, #2, and #3.

- Butan-2-one (a catalyst): Synthesis starts with the oxidation of butan-2-ol using potassium permanganate (KMnO4). KMnO4 is produced through the process in Equation (6) [56].

Reaction (6) involves several elements and compounds and embodies mining and specialized manufacturing processes, leading to observations #1, #2, and #3 as before.

Up to now, all the reagents except the potassium hydroxide (KOH) have been discussed.

- Potassium hydroxide: is produced from potassium chloride and electrolysis as per Equation (7) [57].

2 KCI (aq) + 2 H2O (1) → 2 KOH (aq) + Cl2 (g) + H2 (g)

- Potassium chloride (KCl): This is obtained from underground mines. Underground deposits of sylvinite, carnallite, or potash are mined, and KCl is extracted [57]. Butan-2-ol is produced from the acid-catalyzed (sulfuric acid (H2SO4)) hydration (use of water) of but-1-ene or but-2-ene (both of which are obtained from the cracking of crude oil) [58]. In turn, H2SO4 is obtained from the contact process, which requires sulfur (S (s)) and oxygen (O2 (g)) [59]. Reaction (7) likewise involves several processes, including mining and manufacturing, leading to observations #1, #2, and #3.

Lead Iodide (PbI2): Lead iodide is formed from the ion exchange reaction between lead nitrate and potassium iodide [60] (Equation (8)).

Pb(NO3)2 (aq) + 2 KI (aq) → PbI2 (s) + 2 KNO3O (aq)

- Potassium iodide: Produced by the reaction of KOH with HI, discussed earlier [57].

- Lead nitrate: Formed by the reaction of lead oxide (PbO) and nitric acid (HNO3) according to Equation (9) [44].

PbO (aq) + 2 HNO3 (aq) → Pb(NO3)2 (aq) + H2O (1)

Regarding Equation (9), the origins of PbO and HNO3 need further investigation.

- PbO (yellow lead oxide): Obtained by heating pure lead in the presence of oxygen, leading to direct oxidation [44]. Pure lead is extracted from its most prominent ore, galena, by melt processing [61]. Observations #1 and #2 hold, owing to the mining processes involved.

- Nitric acid: Produced through the Ostwald process in Equation (10), where all the reagent production has already been discussed.

2 NH3 (g) + 4 O2 (g) + H2O (1) → 3 H2O (g) + 2 HNO3 (aq)

Equation (10) involves mostly manufacturing; hence, observation #3 is applicable.

- Methyl Amine (CH3NH2) is synthesized through the reaction of ammonia with methanol in the presence of an aluminium silicate catalyst, as shown in Equation (11) [62].

- Ammonia has been discussed before.

- Kaolinite (a clay mineral, Al2Si2O5(OH)4, the catalyst): Obtained from mining minerals such as feldspar [44]. Owing to manufacturing processes, observation #3 applies.

- Methanol: Produced from the combination of syngas (H2 and O2 gas combined) and CO or CO2 via a hydrogenation reaction, as per Equation (12) [63].

3 H2 (g) + CO (g) → CH3OH (1)

3 H2 (g) + CO2 (g) → CH3OH (1) + H2O (1)

Equations (12) and (13) describe similar processes; however, since Equation (12) does not produce water as a byproduct, it would usually be preferred over Equation (13). That said, water as a byproduct may reduce overall cost, as per proposition Cp5 (refer below).

- CO and CO2: Obtained from burning natural gas or hydrocarbons [64].

- Dimethylformamide (C2H7ON): Requires the reaction of dimethylamine ((CH3)2NH) with carbon dioxide (CO2 gas) in the presence of a zinc chloride catalyst [65].

- Dimethylamine: Produced by the reaction between methanol and ammonia (Equation (14), all of which have been described earlier.

NH3 (aq) + CH3OH (1) → (CH3)2NH (aq) + 2 H2O (1)

Equation (14) involves manufacturing; hence, observation #3 applies.

Additionally, we have the following, as per Figure 4:

- Zinc chloride catalyst (ZnCl2): Reacting the zinc metal (Zn (s)) with hydrochloric acid (HCl (aq)), producing the catalyst and water as a byproduct.

- HCl: Reaction between hydrogen and chlorine gas [59].

- Chlorine gas is obtained from the electrolysis of brine (NaCl and KCl solution) to release Cl2 gas [66].

- Isopropyl alcohol (C3H8O): The hydration of propene, using sulfuric acid as a catalyst, is the main industrial method of synthesis for isopropyl alcohol [67].

- Propene: Obtained by steam cracking and fractional distillation of saturated hydrocarbons obtained from natural gas and crude oil [67].

The above equations are summarized in the Appendix A to this article. In each of the processes above, a selection of mining, manufacturing, and laboratory sectors are involved. Either byproducts or waste occurs, and transporting the raw product and chemical compounds to the fabrication site is involved.

From the above discussions, the following propositions emerge.

- Proposition Cp5: The chemical processes towards the fabrication of PSCs lead to the generation of additional compounds, as follows:

- ➢

- Byproducts, such as water or nitrogen, result, and these may be sold or used in other processes, reducing the cost of the process.

- ➢

- Waste, e.g., acid mine drainage (AMD), may be recycled and reused (cf. our observations #1 and #2).

Linking with the waste aspect in proposition Cp5, we note that mining operations have other severe environmental effects, e.g., water and soil pollution, which should be addressed [48].

- Proposition Cp6: The supply chain of chemical processes involves materials from mining, fabrication in a factory, and laboratory processes.

- ➢

- A costing method is needed for each process to follow the material flow of each product and chemical substance and to quantify it in physical and monetary units.

Regarding proposition Cp6 and our set of delimitations in Section 2.2, follow-up work would investigate the production of the other layers of the PSC device in Figure 3. Arguably, only then can quantitative measurements regarding the cost of PSC fabrication, waste and recycling be assumed.

The discussion in Section 4.1 answers our RQ1: Which chemicals are needed to fabricate a perovskite layer in a solar cell?

Next, we consider aspects of the mining of the ore, its transportation and recycling, and MFCA.

4.2. Mining of Ore

To fabricate a perovskite layer, some of the raw materials need to be mined, such as iodine from caliche ore deposits [45,46], magnetite from iron ores [52], and lead from galena [61]. During the mining of ore, operational costs are incurred, such as mining and milling (technical operating costs of a given mining project, characterized by equipment operation and maintenance, electricity and fuel use, chemicals, and technical personnel) and general and administrative (management of personnel, legal and accounting costs, and logistics in addition to other miscellaneous non-technical expenses) [68]. According to [68], the type of mining, milling, and mineral influence the costing.

The above discussion leads to our next content proposition:

- Proposition Cp7: The cost of mining ore can, amongst others, be divided into mining and milling; resources, e.g., electricity and fuel; administrative, e.g., wages and salaries of personnel; logistics; general; and miscellaneous expenses.It also leads to the following associate proposition:

- Proposition Ap2: The types of mining, milling, and mineral recovery affect the cost of the rest of the supply chain.

4.3. Transporting the Raw Materials, Products, and Chemicals

Once the raw materials are mined, they are transported to the factory, where compounds are chemically fabricated. The chemical is subsequently transported to the manufacturing plant or laboratory where the solar cell and later the solar panel are manufactured. Lastly, the solar panel is transported to the distributor and customer. In this supply chain, costs are involved in transportation and CO2 emissions also become a challenge. Hence, ref. [69] recommended shorter routes between mines and manufacturers. This might not always be suitable and achievable. According to [70], transport costs of goods can make up 10% of the cost of a product, leading to the following:

- Proposition Cp8: The shortest route in transporting chemicals and products should be established to reduce CO2 emissions and costs.

4.4. Recycling of Perovskite Modules

Part of a solar cell’s environmental footprint that needs to be considered is when it needs to be deconstructed at the end of its life [71,72,73]. Reusable parts of the module are identified and removed, whereas parts that are not reusable will be introduced into the environment [74]. The economic, environmental, social, and technological sectors must keep electronic waste from entering landfills through recycling [71], leading to the following:

- Proposition Cp9: Costing all end-of-life processes ought to be conducted since the business that sold the solar panel and the customer might not be the only responsible parties.

4.5. Perovskite Solar Cell Degradation

Perovskite materials have an inherent stability towards moisture and heat; hence, their degradation under such conditions must be considered in their application to PV technology [75]. Moreover, this creates another aspect that should be considered when considering the material flows involved in this study. Naturally, these degradation pathways are readily combatted by encapsulation of the devices [76], and we will include two basic types for illustrative purposes.

MAPbI3 generally decomposes to MAI and PbI2 under thermal stress. That said, the topic is currently being debated in the field, with several pathways suggested. What is evident is that the following products result from long exposure to heat (as suggested by [77]):

NH3 (g), CH3I (s), and PbI2 (s)

Exposure to moisture leads to similar degradation products, which include the following:

CH3NH3I

(aq) and PbI2 (aq)

Other degradation pathways exist, such as through oxygen or photocatalytic degradation. These pathways may be treated similarly to what we proposed for the above. We note that the degradation of a PSC supports proposition Cp9.

4.6. Material Flow Cost Accounting, a Match for Perovskite Solar Cell Fabrication

Stakeholders pressure companies to reduce their negative environmental footprints, such as the use and availability of scarce natural resources and energy and emitting emissions. Although renewable energy sources could avert the global energy crisis, the challenge for managers and accounting professionals lies within their recognition and measurement [78]. Specialized accounting systems were developed to assist management in addressing climate change, emissions and waste using limited natural resources and stringent environmental regulations [15]. Hence, environmental management accounting (EMA) was developed with materials and energy accounting and reporting as a subset of accounting to identify environmental costs during manufacturing.

EMA consists of various environmental management accounting practices (EMAPs) and two (2) branches, monitoring the monetary (MEMA) and physical flows (PEMA) [79] during production, have been developed. Managing the physical and the monetary flows in production results in the costing of a product becoming interdisciplinary [80] since management accountants (monetary) and engineers and technicians (physical) monitor the flow of material, water, and electricity. Despite numerous cost accounting practices, a practice that monitors the flow of materials, energy, and waste in a physical and monetary form might be the answer. Material flow cost accounting (MFCA) is one such practice that also traces waste, emissions, and nonproducts while simultaneously increasing the company’s economic and environmental performance [15]. Hence, it is plausible that MFCA can assist in producing cleaner energy by lessening the waste that occurs when using scarce resources and ensuring the minimization of greenhouse gases (GHGs).

MFCA has been used successfully in other manufacturing industries as per the following case studies. Aluminium gravity die casting in electrical product manufacturing was researched, and the results indicated that the company had a negative product cost margin of 27.38% as a result of MFCA analysis, a negative material cost, a negative system cost, and a negative energy cost when processing 300 kg of raw material [81]. Ref. [81] found MFCA to be a suitable costing method. Ref. [82] did two qualitative case studies in a major Japanese manufacturing company that introduced MFCA in two different supply chains. It was found that MFCA plays a significant role, from an economic and environmental perspective, in coordinating material flows and eliminating sub-optimization in the supply chain. Furthermore, the principal company acts as an MFCA leader in the chain when implementing MFCA. Ref. [83] studied the implementation of MFCA in two companies used as case studies. The first case study was conducted in a powder coating company, while the second was in a sunflower oil production company. Both companies implemented MFCA effectively. The following were identified: Cost of waste, additional costs due to waste recycling, and possible savings. Case study 1 revealed that MFCA, combined with job order costing enable detailed efficiency analyses for each order. However, case study 2 revealed the shortcomings of MFCA in evaluating byproducts.

MFCA is based on four (4) principles: understanding material flow and energy use; linking physical and monetary data; ensuring accuracy, completeness, and comparability of physical data; and estimating and assigning costs to material losses [15]. The four (4) fundamentals of MFCA are quantity centers where material balances are calculated in physical and monetary units; the measuring of material balances of inputs and outputs in physical units to identify inefficiencies (raw materials (input) become the end product and waste (output)); cost calculations, e.g., material (purchase), energy (fuel, steam, and heat), system (in-house handling of material flows), and waste management costs; and a material loss flow model should be developed to visually represent the process. This shows all the quantity centers where the materials are transformed, stored, or used and the flow of these materials within the system’s boundary. Ref. [15] argues that waste generation should be reduced, thereby increasing resource use and cost efficiency. MFCA, an ISO [84] standard, is identified as a possibility to reduce waste in the perovskite level fabrication process of a solar cell, as MFCA focuses on reducing waste at the source [85]. One of the processes in the fabrication of the perovskite level of the solar cell results in up to 90% of the material used being wasted in the spin coating [71]. Furthermore, hidden waste recovery costs could also be identified through MFCA [85]. MFCA can also be employed within the entire supply chain, according to [15].

Consequently, we arrive at two (2) content propositions (one in preliminary form) and a consequential proposition, as follows:

- Proposition Cp10a: MFCA traces and assesses the flow of materials and attempts to reduce waste at the source.

- Proposition Cp11: MFCA can be employed to cost the perovskite fabrication supply chain.

- Proposition Cons_p1: An MFCA waste recovery strategy to reduce an industry’s environmental impact and improve its economic performance facilitates waste reduction during fabrication.

According to [71], each photovoltaic (PV) module has environmental, ecological, and economic costs during fabrication, use, and disposal. Therefore, during the fabrication of the perovskite layer, the following should be measured: raw materials, solvents, gases, and electrical and heat energies. A utilization rate is established and can assist in identifying waste [71]; hence, an EMAP, such as MFCA, may be most suitable. However, ref. [86] rejected the opinion that one EMAP is the answer to complex manufacturing processes. Therefore, it is plausible that more than one EMAP may need to be identified and utilized.

The above discussion on MFCA finalizes an earlier proposition, as follows:

- Proposition Cp10: MFCA traces and quantifies the flow of materials. It:

- ➢

- aims to reduce waste at the source;

- ➢

- assists in measuring materials, solvents, gases, and electrical and heat energies in fabricating the perovskite layer.

Ref. [87] analyzed 73 case studies and identified the following three (3) top reasons why companies employed MFCA: economic (such as reduction of costs or identification of hidden costs), environmental (such as reduction of waste or reduction of environmental impact), and organizational (such as using MFCA as a tool to enhance quality or improving processes). These reasons lead to the following:

- Proposition Cp11: MFCA can achieve the following:

- ➢

- reduce costs (more economical solar panels—societal impact).

- ➢

- reduce waste and environmental impacts (sustainable alternative energy).

- ➢

- enhance quality and improvement of processes (leading to improved solar panels).

According to the ISO 14051 standard [84], all industries that use materials and energy of any type and scale, with or without environmental management systems, can use MFCA (Clause 1, ISO 14051:2011). MFCA measures inventory levels and material flows, and materials include all raw materials, parts, and components. Material losses can be viewed as waste, air emissions, and wastewater [15]. Resource use and cost efficiency can increase, and waste production decreases using MFCA, as waste and resource losses occur at any step in a process [15]. Waste and resource losses include material loss during the process, defective products, and impurities. For instance, materials can remain in laboratory equipment during spin coating following set-ups. Auxiliary materials, such as solvents, detergents for washing equipment, and water can also be identified. Lastly, raw material that becomes unusable during the process is also viewed as a material loss.

The above discussions lead to the following:

- Proposition Cp12: MFCA can measure material loss and residue in laboratory equipment during a process and can identify auxiliary materials.

The implementation of MFCA involves five (5) steps: engaging management and determining roles and responsibilities; setting the scope and boundary of the process and establishing a material flow model; allocating costs; interpreting and communicating the MFCA results; and improving production practices and reducing material loss using MFCA [15]. Therefore, it is important to secure management’s buy-in from the start, as indicated in [88], in the context of correct software engineering processes. The vital role to be played by management and governance structures in adopting techniques is captured by the following:

- Proposition Cp13: It is vital for a PSC’s management and governance structures to buy into using MFCA to address costing aspects and environmental challenges incurred through the company’s operations.

The discussions in Section 4.3, Section 4.4 and Section 4.5 answer our RQ2: To what extent is material flow cost accounting (MFCA) a suitable costing method for fabricating the perovskite solar cell layer in the supply chain? Naturally, environmental concerns should also be addressed in the application of MFCA.

4.7. Discussion of Findings

The article’s main aim is to establish the suitability of MFCA in producing perovskite solar cells and, ultimately, the solar panel, considering the entire supply chain, and to develop a costing and waste reduction framework for these.

The propositions derived from the detailed discussion of the fabrication of the PSC and the role of MFCA indicate why MFCA can be proposed as a plausible costing method for PSCs. When the dependence on fossil fuels decreases, the need for renewable energy sources increases (Cp1). In Cp2 we postulate that perovskite solar cells (PSCs) may be the technology of choice when embarking on solar cell technology due to certain advantages. PSCs’ relatively simple manufacturing processes at lower temperatures may be more economically feasible to manufacture. The inclusion of Industry 4.0 technologies and aspects of the 6IR regarding renewable energy and nanotechnology may also enhance their economic feasibility.

Should a worldwide demand for PSCs emerge (Cp3), suitable costing methods may need to be devised and employed to make their manufacturing economically feasible. Furthermore, the supply chain of chemical processes involves materials from mining, fabrication in a factory, and laboratory processes (Cp6). A uniform costing method, such as MFCA, for each process that follows the material, waste, and energy flows of each product and chemical substance and which quantifies them in physical and monetary units throughout the complete manufacturing supply chain, from the mining of raw materials to the production of reagent species, fabricating the device, degradation, and recycling, may lead to more affordable, cleaner energy. The role of MFCA will be to identify where waste occurs; track the raw materials, energy and emissions of all origins from start to finish; and cost all materials and their losses, leading to profit for all involved—both companies and solar users.

The fabrication of a PSC involves two or more groups of processes that may be executed in parallel (Ap1) and incur cost savings in placing a product on the market but may increase personnel costs to oversee each process. If the one-step method for fabricating PSCs is preferred (Cp4) since the compound C3H8O is not needed, reduced costs may occur. Furthermore, chemical processes towards the fabrication of PSCs lead to the generation of additional compounds (Cp5). MFCA can assist in identifying byproducts, such as water or nitrogen, which may be sold or used in other processes, reducing the cost of the process. Furthermore, MFCA can identify waste and the cost thereof, such as acid mine drainage (AMD), which may be recycled and reused, leading to more cost savings and a new income stream. MFCA can furthermore measure material loss and residue in laboratory equipment during a process and identify auxiliary materials during PSC fabrication (Cp12).

The cost of mining ore can, among other things, be divided into mining and milling; resources, e.g., electricity and fuel; administrative expenses, e.g., wages and salaries of personnel; logistics; general expenses; and miscellaneous expenses (Cp7). Additionally, the types of mining, milling, and mineral recovery affect the cost of the rest of the supply chain (Ap2).

All products and byproducts need to be transported at some stage, which may increase emissions. MFCA can assist in the identification of such emissions. The shortest route for transporting chemicals and products should be established to reduce CO2 emissions and costs (Cp8). MFCA can also be employed to cost all end-of-life processes, which is important since the business that sold the solar panel and the customer might not be the only responsible parties (Cp9). It is furthermore proposed in Cons_p1 that an MFCA waste recovery strategy to reduce an industry’s environmental impact and improve its economic performance can facilitate waste reduction during fabrication. Cp11 argues that MFCA can cost the perovskite fabrication supply chain by tracing and quantifying the flow of energy, waste and materials (Cp10). MFCA aims to reduce waste at the source and assists in measuring materials, solvents, gases, and electrical and heat energies in fabricating the perovskite layer. Hence, it may lead to a more affordable end product and economic feasibility for the company.

MFCA can, therefore, reduce costs (more economical solar panels—societal impact), reduce waste and environmental impacts (sustainable alternative energy), and enhance quality and process improvement (leading to improved solar panels) (Cp11). Lastly, it is vital for management and governance structures to buy into using MFCA during PSC fabrication to address costing aspects and environmental challenges incurred through the company’s operations (Cp13).

The above motivation for using MFCA in the costing of the fabrication of PSCs likewise validates the use of our qualitative propositions, the theory of which is developed in [20].

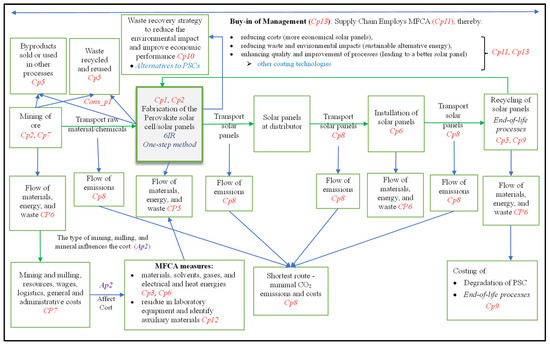

Next, we present our conceptual framework, which is the deliverable of this work. A framework may take several forms, such as a list of guidelines, a table [89], or a diagram. Our framework in this article embodies a diagram developed from the three (3) sets of propositions developed prior. Presented in Figure 5, this is coined a PSC-MFCA framework and was developed to apply MFCA in the supply chain fabrication of the perovskite layer in Figure 3.

Figure 5.

Conceptual framework (PSC-MFCA) for applying MFCA in fabricating the perovskite layer and the supply chain (constructed by researchers).

5. Discussion

Our PSC-MFCA framework in Figure 5 depicts several entities linked through associations. Association Ap2 depicts a link between mining and milling aspects, on the one hand, and MFCA measures, as discussed above. Several other associations are depicted in the framework but not labelled. These have been identified through inspection of interactions among the entities in the framework and will be an avenue for future research in this area, as indicated in the future work section. The content propositions have been included in the respective entities, and the consequential proposition has been indicated as a consequence, where applicable.

The framework in Figure 4, shown above, is embedded in the entity “Fabrication of the perovskite solar cell/solar panels,” as informed by propositions Cp1 and Cp2. The framework’s content displays the supply chain character of the processes described in this article. Aspects embedded in the framework are mining, milling, flow of materials and emissions, waste and byproduct generation, transport, fabrication of the perovskite, and MFCA costing and waste reduction.

The researchers note that our Figure 5 framework is a hybrid structure in that it embeds both static and dynamic aspects. The dynamic aspect is illustrated in the part on transporting a perovskite solar cell. We note that the embedded Figure 4 framework is also a dynamic structure in that fabrication takes place in a bottom-up fashion.

6. Hypothetical Case

Synthesis of the Case: Consider Timeous Generation Solar (TGS), a company that manufactures industrial PSCs. TGS has a management division that determines its strategic directions; a combined science and engineering section tasked with fabricating the perovskite cells; an HR division dealing with personnel aspects, and a finance section that tracks and reports on profits, losses; and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) activities from one financial period to the next and generates forecasting information for management.

The company is situated on a single premises some distance from the mine from which it procures the raw materials for manufacturing its PSCs. Procuring and transporting raw materials from the mine is known to be a costly endeavor. TGS employs a group of scientists and engineers in its laboratory who work together on a single task before moving on to the next. The manufacturing of the PSCs is likewise costly, and the company would like to address these costs.

The company uses generic techniques from the perovskite industry in manufacturing its PSCs, and management wishes to expand its operations by establishing additional centers with laboratories, HR, and finance divisions to tap into the growing solar energy market.

Neither TGS nor the mine from which they obtain their ore is familiar with emerging environmental compliance regulations regarding PSC manufacturing.

- End of Synthesis

Next, we illustrate the utility of our frameworks in Figure 4 and Figure 5 by analyzing the challenges in the case.

- Validation of the MFCA framework for manufacturing PSCs

Our MFCS-PSC framework in Figure 5, which embeds the chemical process framework in Figure 4, can be applied to assist TGS in streamlining its operations, improving its profit margins, reducing costs, and complying with environmental considerations, as discussed next.

Starting with the science and engineering section, some of the manufacturing processes involve decisions to be taken. The generation of MAPbI3 by Equation (1) in Section 4.1 and indicated in Figure 4 necessitates a decision regarding the one-step or the two-step process. Since the one-step process does not need C3H8O (isopropanol), our proposition Cp4 suggests a one-step for the said generation. This implies a cost saving. That said, C3H8O could be used in a subsequent process. Since the company uses generic PSC technology, we suggest establishing a research and development (R&D) section to investigate these possibilities.

Similar considerations hold for the generation of methanol (CH3OH) in Figure 4 and as specified by Equation (12) or (13). Equation (12) does not produce water as a byproduct and may be cheaper. However, again, water could be used in subsequent or other chemical processes, such as producing I2 from brines or leaching through water, as per Equation (13). Additionally, iodine may be sourced from brines or leached through water per our observation #1. Our R&D section mentioned above could investigate these costing considerations further. Proposition pC5 makes a statement in this regard, also concerning the nitrogen generated by Equation (2) and indicated in our Figure 4 sub-framework.

Regarding TGS’ expansion through creating subsidiaries, we suggest that the present premises be rebranded as the head office and subsidiaries be established at premises closer to the mine supplying the ore. This way, transport costs and CO2 emissions may be reduced and monitored through MFCA in line with proposition Cp8 indicated in our main framework in Figure 5. Oxygen is used in several reactions and may be sourced from oxygen plants. Management should consider making one of the subsidiaries such a plant. The production of styrene may be achieved through the cracking of crude oil, again obtained through mining activities, which could be expensive. If the crude oil direction is taken, then one of the subsidiaries could be established closer to the premises of the drilling company. The R&D, accounting, and HR divisions should investigate these considerations.

Regarding personnel and HR aspects, establishing subsidiaries would imply an initial capital layout by setting up premises and employing more qualified personnel. This would increase TGS’ salary bill but ensure job creation for society. Compounded with this is a possible parallel fabrication of materials, as indicated by propositions Ap1 and Ap2 in the two frameworks. Fabrication time would be saved, but salary and wages would increase. The R&D, accounting and HR divisions could investigate these.

Turning to the mine supplying the ore and raw materials for further processing, we note that the mine may incur environmental challenges through waste production, AMD, etc. Presumably, our PSC company has little or no control over the mining activities, but in the spirit of this article, MFCA could be used to monitor and suggest improvements through its two branches, PEMA and MEMA, for both the mine and TGS. PEMA could be used for tracking physical aspects, namely, the mining of ore and the flow of materials in the PSC company. These could involve chemicals, compounds, materials losses, energy usage, hidden waste, and reducing waste at the source and the manufacturing of the PSC, e.g., addressing residue in laboratory equipment. MEMA could be used for costing the processes and materials by employing supply chain management (SCM) in line with proposition Cp11, thereby improving the company’s economic performance. An MFCA subdivision could be established in the R&D section to assist with the flow of materials, energy, water and waste and the relevant costing aspects and to reduce the negative impacts on the ecosystem and society.

Environmental and societal aspects should receive prominence. MFCA’s ISO 14051 could assist TGS in brushing up on using MFCA to address environmental and societal challenges. The same would hold for the mine or future mines from which the company could procure the raw materials. Naturally, a commitment from management and the company’s governance structure would be needed in line with proposition Cp13.

- End of validation

7. Conclusions

This article considered the fabrication of the perovskite layer of a solar cell, with the mining of the ore as the starting point and, finally, the device itself. The chemical processes and reactions involved in fabricating the cell were unpacked and synthesized in Figure 4 by considering the diagram in a bottom-up fashion. Several propositions and observations were synthesized from the reactions, and options were considered, amongst others, when forming byproducts that could either be deemed to be unwanted, used in subsequent reactions, or sold to defray some of the cost of the processes. Costing aspects were considered beginning with the cost of the raw materials to fabricate the perovskite layer.

MFCA, which monitors physical and monetary flows using PEMA and MEMA, was suggested as a costing mechanism for chemical processes. MFCA has several benefits for the company, environment, and customers. Producing more economical solar panels reduces costs for companies and, ultimately, more affordable energy for customers. The environmental impact is less when waste and other environmental effects, such as GHGs, lead to a more sustainable alternative energy supply. Lastly, MFCA can enhance the quality and improvement of processes, which may result in improved solar panels.

Further propositions were formulated, and a PSC-MFCA framework for costing PSCs and reducing waste was developed in Figure 5 of this article. The Figure 4 framework modelling the chemical processes is included as an entity in Figure 5. The utility of the PSC-MFCA framework was illustrated through a hypothetical case study in Section 6.

7.1. Advancing Theoretical Knowledge

The researchers identified interdisciplinarity regarding the costing of the perovskite layer of a solar cell using MFCA as an under-researched area. Utilizing the theory of qualitative propositions from previous work by [20], a sub-framework for the chemical processes was developed and incorporated into a larger framework on costing the fabrication of a PVC using MFCA. Various costing considerations are included in the MFCA framework, including supply chain management involving mining the ore, the flow of materials, transport costs, curbing emissions, and recycling a PSC having reached the end of its life. The framework contributes to the theory at the intersection of perovskite solar technology and MFCA as a costing and waste reduction mechanism.

In line with Jaakkola’s views [19], conceptual papers may be regarded as breaking new ground in addition to taking stock. Conceptual papers can strive to advance the understanding of phenomena in big leaps rather than incremental steps [19]. The researchers believe this article’s contribution follows suit.

7.2. Practical Implications

The framework in Figure 5 may be viewed as a fine blend between a static and dynamic structure. This indicates the aspects to consider and gives the dynamics of transporting the ore from a mine to the laboratory. The manufacturer may not be able to influence the cost of the raw materials, even as these materials influence the cost of the final product. Therefore, the entire supply chain, from mining the ore; developing the chemicals; and transporting the raw materials, chemicals, and the final product, should be viewed as part of the fabrication of the solar cell to facilitate the affordability of the solar cell.

The static part of the framework would allow a perovskite company to at least initiate a discussion on costing their product and reducing waste. As indicated in the future work section below, the framework should be operationalized to allow a company to use it dynamically, enhancing its practicability. Regarding Figure 4, the chemical processes framework elicits costing options for a company to select, e.g., a one-step or two-step process. As advocated in this article, MFCA could be applied throughout the supply chain to make the product affordable and more environmentally friendly. A further recommendation is that, when a solar panel reaches the end of its life, the manufacturer should recycle the product, yet this is a complex process that should be further researched.

7.3. Novelty of the Work

Two diverse subject areas, PSC technology and MFCA, were brought together to cost the fabrication of a PSC, making theoretical and practical contributions. To this end, our work lays the foundation for further investigation with these as core areas. The frameworks we developed in Figure 4 and Figure 5 are unique in that previous work by the authors embedded mostly static frameworks; for example, the framework in [47]. As indicated, both frameworks in the present article embody dynamic structures. We believe dynamism is the next development of our work. Naturally, a dynamic structure specifies, albeit implicitly, an algorithm that may be programmed and, therefore, automated.

7.4. Limitations

The work presented in this article is conceptual and aims to begin a discussion in perovskite companies about costing their products. Part of the framework has a static character, one which should be operationalized to elicit an underlying algorithmic and dynamic component. This would allow a company to follow sequences of steps in fabricating their PSCs.

7.5. Future Work

Future research in this area may be pursued along several avenues. As indicated above, the MFCA framework should be operationalized by adding a dynamic component for the static part. In-depth research on costing relevant raw materials, energy flow, and emissions from solar cell manufacturing should be undertaken. Case studies using our framework should be undertaken in one or more companies to determine its scalability and enhance its costing abilities through quantitative means. Part of this industry work would be conducting surveys among practitioners in the perovskite solar industry. Further investigation into the production of the other layers comprising the PSC device and how the PSC-MFCA framework developed here may be applied to those layers is also of interest. Once these analyses have been completed, and as indicated in the above limitations, the work is conceptual and qualitative; hence, follow-up work should embark on quantitative measurements regarding the cost of PSC fabrication, waste, degradation and the recycling of usable parts of a perovskite cell at the end of its usable life. As indicated above, quantitative assessments can commence once all of the layers in the PSC structure shown in Figure 3 have been analyzed.

Regarding the technical aspects, the spin coating method introduced in this article may not be the most efficient regarding the minimization of waste. Other methods were indicated in this article, and these should be investigated when the other layers in the Figure 3 framework are analyzed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.v.d.P. and H.M.v.d.P.; formal analysis, H.J.v.d.P., H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; investigation, H.J.v.d.P. and H.M.v.d.P.; methodology, H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; project administration, H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; resources, H.J.v.d.P., H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; validation, H.J.v.d.P., H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; visualization, H.J.v.d.P., H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P.; writing—original draft, H.J.v.d.P. and H.M.v.d.P.; writing—review and editing, H.M.v.d.P. and J.A.v.d.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding other than part of the APC defrayed by the University of South Africa (UNISA).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COP | Conference of Parties |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| ETL | Electron transporting layer |

| FA | Formamidinium |

| FTO | Fluorine-doped tin oxide |

| HTL | Hole transporting layer |

| IPA | Isopropyl alcohol |

| ITO | Indium doped tin oxide |

| MA | Methyl ammonium |

| MFCA | Material flow cost accounting |

| PSC | Perovskite solar cell |

Appendix A. Production of Chemicals

This table provides the equations for producing each of the seven (7) chemicals used in the one- or two-step method described above.

| Chemical | Equation | Byproducts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH3NH3I | CH3NH2 (aq) + HI (aq) → CH3NH3I (s) | (1) | |

| Hydrogen iodide (HI) | 2 I2 (aq) + N2H4 (aq) 4 HI (aq) + N2 (g) | (2) | Nitrogen gas (N2) |

| Iodine (Equation (2)) | 2 NH3 (g) + H2O2 (aq) N2H4 (aq) + 2 H2O (l) | (3) | Water |

| N2 (g) + 3 H2 (g) 2 NH3 (g) | (4) | ||

| Nitrogen gas, hydrogen gas and iron (Equation (4)) | H2 (g) + O2 (g) H2O2 (aq) | (5) | |

| 2 MnO2 (aq) + 4 KOH (aq) + O2 (g) 2 K2MnO4 (aq) + 2 H2O (l) 2 KMnO4 (aq) + 2 KOH (aq) + H2 (g) | (6) | ||

| 2 KCl (aq) + 2 H2O (l) 2 KOH (aq) + Cl2 (g) + H2 (g) | (7) | ||

| Lead iodide (PbI2) | Pb(NO3)2 (aq) + 2 KI (aq) PbI2 (s) + 2 KNO3 (aq) | (8) | |

| PbO (aq) + 2 HNO3 (aq) Pb(NO3)2 (aq) + H2O (l) | (9) | ||

| 2 NH3 (g) + 4 O2 (g) + H2O (l) 3 H2O (g) + 2 HNO3 (aq) | (10) | ||

| Methyl amine (CH3NH2) | NH3 (aq) + CH3OH (l) H2O (l) + CH3NH2 (aq) | (11) | |

| 3 H2 (g) + CO (g) CH3OH (l) | (12) | ||

| 3 H2 (g) + CO2 (g) CH3OH (l) + H2O (l) | (13) | ||

| Dimethylformamide (C2H7ON) | NH3 (aq) + CH3OH (l) → (CH3)2NH (aq) + 2H2O (l) | (14) | |

References

- United Nations Environment Programme; International Resource Panel. Global Resources Outlook 2024–Bend the Trend Pathways to a Liveable Planet as Resource Use Spikes; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Climate Action. Renewable Energy–Powering a Safer Future. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/raising-ambition/renewable-energy (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- United Nations. Conference of Parties (COP); United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Sustainable Development Goals Booklet; Sustainable Development Goals 2015; United Nations Development Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, R.; Chen, A. Blessing Or Curse Energy Sustainability: How does Climate Change Affect Renewable Energy Consumption in China? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adwek, G.; Boxiong, S.; Ndolo, O.O.; Siagi, Z.O.; Chepsaigutt, C.; Kenmunto, C.M.; Arowo, M.; Shimmon, J.; Simiyu, P.; Yabo, A.C. The Solar Energy Access in Kenya: A Review Focusing on Pay-as-You-Go Solar Home System. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3897–3938. [Google Scholar]

- Igliński, B.; Skrzatek, M.; Kujawski, W.; Cichosz, M.; Buczkowski, R. SWOT Analysis of Renewable Energy Sector in Mazowieckie Voivodeship (Poland): Current Progress, Prospects and Policy Implications. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 77–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C.H.; Lim, H.N.; Hayase, S.; Zainal, Z.; Huang, N.M. Photovoltaic Performances of Mono- and Mixed-Halide Structures for Perovskite Solar Cell: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 248–274. [Google Scholar]

- Fakharuddin, A.; Jose, R.; Brown, T.M.; Fabregat-Santiago, F.; Bisquert, J. A Perspective on the Production of Dye-Sensitized Solar Modules. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meillaud, F.; Boccard, M.; Bugnon, G.; Despeisse, M.; Hänni, S.; Haug, F.-J.; Persoz, J.; Schüttauf, J.-W.; Stuckelberger, M.; Ballif, C. Recent Advances and Remaining Challenges in Thin-Film Silicon Photovoltaic Technology. Mater. Today 2015, 18, 378–384. [Google Scholar]

- Weyand, S.; Kawajiri, K.; Mortan, C.; Zeller, V.; Schebek, L. Are Perovskite Solar Cells an Environmentally Sustainable Emerging Energy Technology? Upscaling from Lab to Fab in Life Cycle Assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 14010–14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune Business Insight. Perovskite Solar Cell Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, by Type (Rigid and Flexible), by End-User (BIPV, Power Station, Transportation & Mobility, Consumer Electronics, and Others) and Regional Forecast, 2024–2032. 2025. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/industry-reports/perovskite-solar-cell-market-101556 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Čulík, P.; Brooks, K.; Momblona, C.; Adams, M.; Kinge, S.; Maréchal, F.; Dyson, P.J.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Design and Cost Analysis of 100 MW Perovskite Solar Panel Manufacturing Process in Different Locations. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 3039–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajal, P.; Verma, B.; Vadaga, S.G.R.; Powar, S. Costing Analysis of Scalable Carbon-Based Perovskite Modules using Bottom Up Technique. Glob. Chall. 2021, 6, 2100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, K.D. Manual on Material Flow Cost Accounting: ISO14051-2014; Asian Productivity Organization (APO): Tokyo, Japan, 2014; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.; Gunarathne, N. An Exploration of the Implementation and Usefulness of Environmental Management Accounting: A Comparative Study between Australia and Sri Lanka. CIMA Res. Exec. Summ. 2019, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll, H.J.; van der Poll, H.M. Manufacturing and Costing Perovskite Solar Cells for a Brighter Future. In Proceedings of the Academy for Global Business Advancement 2023 Conference, Le Méridien Dubai Hotel & Conference Centre (Dubai Airport), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 20–22 May 2023; pp. 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.N.K.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 9th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, E. Designing Conceptual Articles: Four Approaches. AMS Rev. 2020, 10, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- van der Poll, J.A.; van der Poll, H.M. Assisting Postgraduate Students to Synthesise Qualitative Propositions to Develop a Conceptual Framework. J. New Gener. Sci. 2023, 21, 146–158. [Google Scholar]

- Jabareen, Y. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Jacak, J.E.; Jacak, W.A. Routes for Metallization of Perovskite Solar Cells. Materials 2022, 15, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. COP26: Together for our Planet; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Green, F.; van Asselt, H. Opinion: COP27 Flinched on Phasing Out ‘all Fossil Fuels’. What’s Next? United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Climate Change. COP 28: What Was Achieved and What Happens Next? United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2017; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 1–782. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Coal 2023: Analysis and Forecast to 2026; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023; pp. 1–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus, S.; Luque, A. Achievements and Challenges of Solar Electricity from Photovoltaics. In Handbook of Photovoltaic Science and Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, N.; Teshima, K.; Miyasaka, T. Conductive Polymer–carbon–imidazolium Composite: A Simple Means for Constructing Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Commun. 2006, 16, 1733–1735. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, A.; Teshima, K.; Shirai, Y.; Miyasaka, T. Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic. Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6050–6051. [Google Scholar]