Fostering Sustainable Marine Product Consumption: Understanding the Impact of Food-Related Lifestyles and Social Influences on Attitudes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Objectives

1.2. Research Contribution

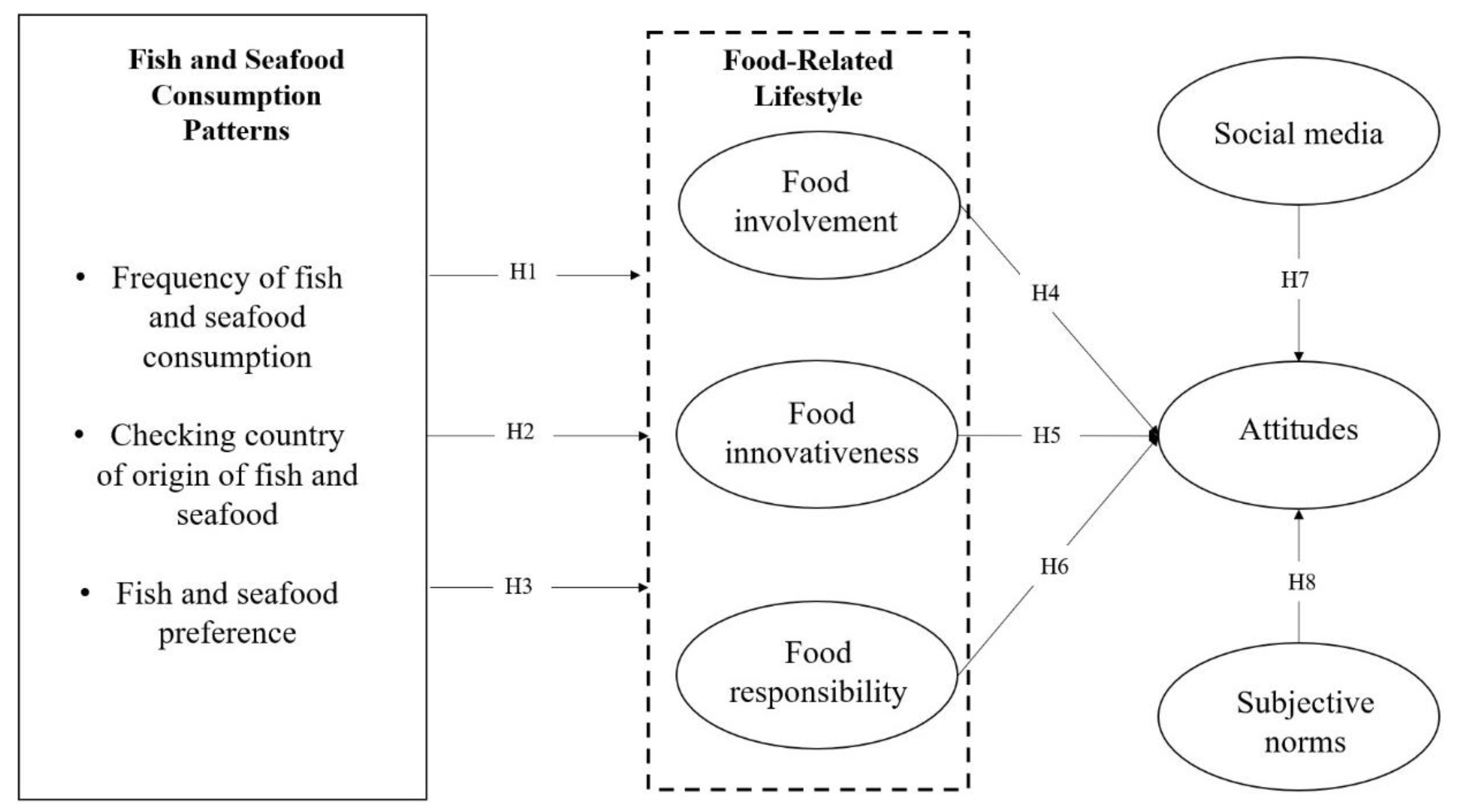

2. Research Framework

2.1. Marine Product Consumption Behavior and Food-Related Lifestyle

2.2. Food-Related Lifestyle and Attitudes

2.3. Subjective Norms, Information-Seeking Behavior on Social Media, and Attitudes Toward Marine Product Consumption

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Construct Measurement

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Profile of Respondents

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Testing of Hypotheses

4.3.1. Differences Between Marine Product Consumption Patterns and Food-Related Lifestyle

4.3.2. Structural Model Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Study Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arenas-Gaitán, J.; Peral-Peral, B.; Reina-Arroyo, J. Food-Related Lifestyles across Generations. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1485–1501. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, R.C.; Rodrigues, H.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Consumption, Knowledge, and Food Safety Practices of Brazilian Marine Products Consumers. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109084. [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci, D.; Nocella, G.; De Devitiis, B.; Viscecchia, R.; Bimbo, F.; Nardone, G. Consumer Purchasing Behaviour towards Marine Products: Patterns and Insights from a Sample of International Studies. Appetite 2015, 84, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thong, N.T.; Solgaard, H.S. Consumer’s Food Motives and Marine Products Consumption. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/66538eba-9c85-4504-8438-c1cf0a0a3903/content/sofia/2024/fisheries-aquaculture-projections.html (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Chung, S.; Hwang, J.T.; Joung, H.; Shin, S. Associations of Meat and Fish/Marine Products Intake with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality from Three Prospective Cohort Studies in Korea. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2023, 67, 2200900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Kim, E. An Analysis of the Impact of Japan’s Treated Wastewater Release from Nuclear Power Plant on Korean Consumption of Marine Products-Focused on Survey Results. J. Fish. Bus. Adm. 2022, 53, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Rural Economic Institute. 2022 Food Balance Sheet; Korea Rural Economic Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2023; Available online: https://www.nkis.re.kr/subject_view1.do?otpId=OTP_0000000000013791 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Haps, S.; New Data Shows Koreans Eat More Seafood Than Rice. Haps Magazine Korea, 17 October 2022. Available online: https://www.hapskorea.com/new-data-shows-koreans-eat-more-seafood-than-rice/ (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Murray, G.; Wolff, K.; Patterson, M. Why Eat Fish? Factors Influencing Marine Products Consumer Choices in British Columbia, Canada. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 144, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Marinac Pupavac, S.; Kenđel Jovanović, G.; Linšak, Ž.; Glad, M.; Traven, L.; Pavičić Žeželj, S. The Influence on Marine Products Consumption, and the Attitudes and Reasons for Its Consumption in the Croatian Population. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 945186. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsø, K.; Scholderer, J.; Grunert, K.G. Testing Relationships between Values and Food-Related Lifestyle: Results from Two European Countries. Appetite 2004, 43, 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich, R.; Elshiewy, O. A Cross-Country Analysis of How Food-Related Lifestyles Impact Consumers’ Attitudes Towards Microalgae Consumption. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 102999. [Google Scholar]

- Brunsø, K.; Birch, D.; Memery, J.; Temesi, Á.; Lakner, Z.; Lang, M.; Grunert, K.G. Core Dimensions of Food-Related Lifestyle: A New Instrument for Measuring Food Involvement, Innovativeness and Responsibility. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 91, 104192. [Google Scholar]

- Stancu, V.; Brunsø, K.; Krystallis, A.; Guerrero, L.; Santa Cruz, E.; Peral, I. European Consumer Segments with a High Potential for Accepting New Innovative Fish Products Based on Their Food-Related Lifestyle. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 99, 104560. [Google Scholar]

- Carrus, G.; Cini, F.; Caddeo, P.; Pirchio, S.; Nenci, A.M. The Role of Ethnicity in Shaping Dietary Patterns: A Review on the Social and Psychological Correlates of Food Consumption. Nutr. Diet.Suppl.Nutr. Cost Anal. Versus Clin. Benefits 2011, 75, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, D.; Franceschini, S.; Buttazzoni, L.; Giannetti, C.; Capoccioni, F. Consumer Preferences for Farmed Seafood: An Italian Case Study. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2020, 29, 445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Garlock, T.; Nguyen, L.; Anderson, J.; Musumba, M. Market Potential for Gulf of Mexico Farm-Raised Fin-Fish. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2020, 24, 128–142. [Google Scholar]

- Onozaka, Y.; Honkanen, P.; Altintzoglou, T. Sustainability, Perceived Quality and Country of Origin of Farmed Salmon: Impact on Consumer Choices in the USA, France and Japan. Food Policy 2023, 117, 102452. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, H.J.; Chae, M.J.; Ryu, K. Consumer Behaviors towards Ready-to-Eat Foods Based on Food-Related Lifestyles in Korea. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2010, 4, 332–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Yoon, J. Analysis of Eco-Friendly Food, HMR Purchases, and Eating-Out Behavior by the Level of Agri-Food Consumer Competency—Based on Food Consumption Behavior Survey for Food 2022 Data. Korean Soc. Food Nutr. 2023, 36, 588–604. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. Korea Targets to Welcome 18.5 Million Foreign Visitors in 2025, Up 13% from 2024. Korea Times. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/culture/2025/02/135_391613.html (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Lim, H.R.; An, S. Intention to purchase wellbeing food among Korean consumers: An application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 88, 104101. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J. K-Food Exports Hit Record $13.03 Billion in 2024, Led by Ramen and Processed Rice Products. BusinessKorea. Available online: https://www.businesskorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=233171 (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Birch, D.; Lawley, M. The Role of Habit, Childhood Consumption, Familiarity, and Attitudes Across Marine Products Consumption Segments in Australia. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, A.C.; Luning, P.A.; Stafleu, A.; De Graaf, C. Food-Related Lifestyle and Health Attitudes of Dutch Vegetarians, Non-Vegetarian Consumers of Meat Substitutes, and Meat Consumers. Appetite 2004, 42, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jungles, B.F.; Garcia, S.F.A.; de Carvalho, D.T.; Junior, S.S.B.; Da Silva, D. Effect of Organic Food-Related Lifestyle Towards Attitude and Purchase Intention of Organic Food: Evidence from Brazil. ReMark-Rev. Bras. Mark. 2021, 20, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, A.; Sinesio, F.; Moneta, E.; Dinnella, C.; Laureati, M.; Torri, L.; Spinelli, S. Measuring Consumers’ Attitudes towards Health and Taste and Their Association with Food-Related Lifestyles and Preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.C.; Lin, T.H.; Lai, M.C.; Lin, T.L. Environmental Consciousness and Green Customer Behavior: An Examination of Motivation Crowding Effect. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 139–149. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.C.; Lau, T.C.; Sarwar, A.; Khan, N. The Effects of Consumer Consciousness, Food Safety Concern, and Healthy Lifestyle on Attitudes toward Eating “Green”. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffry, S.; Pickering, H.; Ghulam, Y.; Whitmarsh, D.; Wattage, P. Consumer Choices for Quality and Sustainability Labelled Marine Products in the UK. Food Policy 2004, 29, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, H. The Influence of Halal Awareness, Halal Certificate, Subjective Norms, Perceived Behavioral Control, Attitude, and Trust on Purchase Intention of Culinary Products among Muslim Customers in Turkey. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2023, 32, 100726. [Google Scholar]

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective Norms, Attitudes, and Intentions of Finnish Consumers in Buying Organic Food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar]

- Folkvord, F.; Roes, E.; Bevelander, K. Promoting Healthy Foods in the New Digital Era on Instagram: An Experimental Study on the Effect of a Popular Real versus Fictitious Fit Influencer on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intentions. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1677. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Dang, A.; Xuan Tran, B.; Tat Nguyen, C.; Thi Le, H.; Thi Do, H.; Duc Nguyen, H.; Ho, R.C. Consumer Preference and Attitude Regarding Online Food Products in Hanoi, Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Driver, B.L. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Leisure Choice. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, B.H.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H. Influential Factors for Sustainable Intention to Visit a National Park during COVID-19: The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior with Perception of Risk and Coping Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P. An Integrative Model of Consumers’ Intentions to Purchase Travel Online. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brécard, D.; Hlaimi, B.; Lucas, S.; Perraudeau, Y.; Salladarré, F. Determinants of Demand for Green Products: An Application to Eco-Label Demand for Fish in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eck, T.; Choi, J. Perceived Risk and Risk Reduction Behaviors in Marine Products Consumption. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1412041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rha, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Nam, Y. A Study on the Relationship between Purchases of Meal Kits and Home Meal Replacements. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2024, 18, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghvanidze, S.; Velikova, N.; Dodd, T.H.; Oldewage-Theron, W. Consumers’ Environmental and Ethical Consciousness and the Use of the Related Food Products Information: The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness. Appetite 2016, 107, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubowiecki-Vikuk, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Machnik, A. Responsible Consumer and Lifestyle: Sustainability Insights. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, C. The Effects of Social Media Use on Preventive Behaviors during Infectious Disease Outbreaks: The Mediating Role of Self-Relevant Emotions and Public Risk Perception. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Item | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 164 | 47.0 |

| Female | 185 | 53.0 | |

| Marriage status | Single | 178 | 51.0 |

| Married | 171 | 49.0 | |

| Age | 20s | 77 | 22.1 |

| 30s | 98 | 28.1 | |

| 40s | 90 | 25.8 | |

| 50s | 61 | 17.5 | |

| Over 60s | 23 | 6.6 | |

| Number of family members (including the respondent) | 1 | 46 | 13.2 |

| 2 | 53 | 15.2 | |

| 3 | 100 | 28.7 | |

| 4 | 123 | 35.2 | |

| Over 5 | 27 | 7.7 | |

| Monthly household income (USD) | 2000 | 33 | 9.5 |

| 2001–4000 | 92 | 26.4 | |

| 4001–6000 | 107 | 30.7 | |

| 6001–8000 | 67 | 19.2 | |

| Over 8001 | 50 | 14.3 | |

| Employment | Office worker | 164 | 47.0 |

| Self-employed | 36 | 10.3 | |

| Professional | 28 | 8.0 | |

| House wife | 34 | 9.7 | |

| Civil servant | 15 | 4.3 | |

| Student | 20 | 5.7 | |

| Not employed | 39 | 11.2 | |

| Other | 13 | 3.7 | |

| Education | Completed high school | 70 | 20.1 |

| Completed University | 248 | 71.1 | |

| Completed graduate school | 31 | 8.9 | |

| Frequency of marine product consumption | Never | 35 | 10.0 |

| Less than four times per month | 159 | 45.6 | |

| 1–2 times per week | 130 | 37.2 | |

| 3–4 times per week | 19 | 5.4 | |

| More than 5 times per week | 6 | 1.7 | |

| Types of marine product consumed | Fish | 122 | 35.0 |

| Shellfish | 18 | 5.2 | |

| Crustaceans | 58 | 16.6 | |

| Mollusks | 115 | 33.0 | |

| Seaweeds | 18 | 5.2 | |

| Dried fish | 18 | 5.2 | |

| Places of marine product consumption | Home | 248 | 71.1 |

| Restaurant | 71 | 20.3 | |

| Cafeteria/canteen | 22 | 6.3 | |

| At friend’s/family | 7 | 2.0 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Checking the country of origin | Yes | 233 | 66.8 |

| No | 116 | 33.2 | |

| Preferences for the origin of marine products | Domestic | 245 | 70.2 |

| Imported | 14 | 4.0 | |

| Does not matter | 90 | 25.8 | |

| Total | 349 | 100 | |

| Factors and Items | Standardized Loading | S.E. | Skew. | Kurt. | C.R. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food involvement (CR = 0.85, AVE = 0.58) | |||||

| Food and drink is an important part of my life | 0.77 | N/A | −0.620 | 0.215 | N/A |

| Eating and drinking are a continuous source of joy | 0.68 | 0.06 | −0.471 | 0.027 | 12.65 |

| Decisions on what to eat and drink are important | 0.85 | 0.07 | −0.569 | −0.006 | 15.40 |

| Eating and food is an important part of my social life | 0.73 | 0.07 | −0.269 | −0.370 | 13.13 |

| Food innovativeness (CR = 0.91, AVE = 0.69) | |||||

| I look for ways to prepare unusual meals | 0.84 | N/A | 0.030 | −0.607 | N/A |

| Recipes and articles on food from other culinary traditions encourage me to experiment in the kitchen | 0.87 | 0.06 | 0.339 | −0.555 | 18.78 |

| I like to try new foods that I have never tasted before | 0.79 | 0.06 | 0.319 | −0.688 | 16.05 |

| I love to try recipes from different countries | 0.83 | 0.06 | 0.264 | −0.841 | 17.13 |

| Food responsibility (CR = 0.82, AVE = 0.53) | |||||

| Try to choose food that is produced in a sustainable way | 0.77 | N/A | −0.506 | −0.369 | N/A |

| Try to buy organically produced foods | 0.79 | 0.07 | −0.089 | 0.411 | 13.61 |

| Try to choose food produced with minimal impact on the environment | 0.66 | 0.07 | −0.029 | −0.226 | 11.71 |

| Important to understand the environmental impact of our eating habits | 0.67 | 0.07 | −0.489 | −0.382 | 11.64 |

| Attitudes (CR = 0.89, AVE = 0.62) | - | ||||

| … like to eat marine products | 0.64 | N/A | −0.489 | −0.208 | N/A |

| Eating marine products is a happy thing | 0.74 | 0.06 | −0.350 | −0.151 | 17.81 |

| I am positive about eating marine products | 0.78 | 0.08 | −0.287 | −0.263 | 13.85 |

| Eating marine products is worthwhile | 0.87 | 0.09 | −0.180 | −0.091 | 13.28 |

| Marine product consumption brings me good results | 0.89 | 0.09 | −0.175 | −0.162 | 13.34 |

| Subjective norms (CR = 0.92, AVE = 0.66) | |||||

| My family is positive about my marine product consumption | 0.80 | N/A | −0.561 | 0.425 | N/A |

| My friends are positive about my marine product consumption | 0.84 | 0.05 | −0.167 | 0.302 | 18.28 |

| My acquaintances are positive about my marine product consumption | 0.84 | 0.05 | −0.215 | 0.296 | 18.74 |

| My family would want me to eat marine products | 0.84 | 0.06 | −0.080 | −0.390 | 17.89 |

| My friends would want me to eat marine products | 0.78 | 0.05 | −0.059 | −0.025 | 16.80 |

| My acquaintances would want me to eat marine products | 0.78 | 0.06 | −0.002 | 0.015 | 16.59 |

| Information-seeking behavior on social media (CR = 0.91, AVE = 0.71) | |||||

| Check other people’s posts about marine product consumption | 0.82 | N/A | −0.295 | −0.555 | N/A |

| Search for information on discharging treated water | 0.87 | 0.05 | −0.293 | −0.538 | 18.98 |

| Search for radioactivity tests and procedures | 0.83 | 0.05 | −0.250 | −0.538 | 17.66 |

| Check other people’s opinions on marine product consumption | 0.85 | 0.05 | −0.446 | −0.164 | 18.85 |

| Measures | FRLI | FRLII | FRLIII | ATT | SN | IS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRLI | 0.77 | |||||

| FRLII | 0.24 | 0.83 | ||||

| FRLIII | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.73 | |||

| ATT | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.79 | ||

| SN | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.66 | 0.81 | |

| IS | 0.23 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.84 |

| Dimensions | Frequency | Mean | SD | F/p | Post Hoc Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food involvement | Never (a) | 3.627 | 0.654 | 4.869/0.001 ** | e > b > a |

| Less than 4 times per month (b) | 3.658 | 0.780 | |||

| 1~2 times per week (c) | 3.888 | 0.577 | |||

| 3~4 times per week (d) | 3.789 | 0.731 | |||

| More than 5 times per week (e) | 4.520 | 0.363 | |||

| Food innovativeness | Never (a) | 2.594 | 0.888 | 7.466/0.000 *** | c > b |

| Less than 4 times per month (b) | 2.508 | 0.802 | |||

| 1~2 times per week (c) | 3.003 | 0.874 | |||

| 3~4 times per week (d) | 3.105 | 0.948 | |||

| More than 5 times per week (e) | 3.240 | 1.089 | |||

| Food responsibility | Never (a) | 3.029 | 0.607 | 6.637/0.000 *** | e > d > a |

| Less than 4 times per month (b) | 3.166 | 0.640 | |||

| 1~2 times per week (c) | 3.392 | 0.613 | |||

| 3~4 times per week (d) | 3.631 | 0.900 | |||

| More than 5 times per week (e) | 4.040 | 0.498 |

| Mean | SD | t | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Food involvement | 3.823 | 3.600 | 0.606 | 0.731 | 2.598 | 0.010 * |

| Food innovativeness | 2.790 | 2.654 | 0.878 | 0.887 | 1.360 | 0.174 |

| Food responsibility | 3.403 | 3.014 | 0.634 | 0.648 | 5.274 | 0.000 *** |

| Dimensions | Preferences | Mean | SD | F/p | Post Hoc Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food involvement | Domestic (a) | 3.829 | 0.602 | 5.721/0.004 ** | a > c > b |

| Imported (b) | 3.389 | 0.486 | |||

| Does not matter (c) | 3.622 | 0.780 | |||

| Food innovativeness | Domestic (a) | 2.767 | 0.892 | 4.704/0.010 * | b > a > c |

| Imported (b) | 3.400 | 0.661 | |||

| Does not matter (c) | 2.620 | 0.923 | |||

| Food responsibility | Domestic (a) | 3.029 | 0.646 | 15.422/0.000 *** | c > b > a |

| Imported (b) | 3.166 | 0.504 | |||

| Does not matter (c) | 3.392 | 0.745 |

| Hypothesized Path | Standardized Estimates | T | R2 | Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H4: Food involvement → Attitudes | 0.141 | 2.809 ** | 0.299 | Yes |

| H5: Food innovativeness → Attitudes | 0.048 | 0.826 | 0.261 | No |

| H6: Food responsibility → Attitudes | 0.188 | 3.034 ** | 0.234 | Yes |

| H7: Subjective norms → Attitudes | 0.714 | 10.908 *** | 0.597 | Yes |

| H8: Information-seeking behavior on social media → Attitudes | −0.060 | −1.159 | 0.180 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, S.; Choi, J. Fostering Sustainable Marine Product Consumption: Understanding the Impact of Food-Related Lifestyles and Social Influences on Attitudes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072890

An S, Choi J. Fostering Sustainable Marine Product Consumption: Understanding the Impact of Food-Related Lifestyles and Social Influences on Attitudes. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072890

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Soyoung, and Jinkyung Choi. 2025. "Fostering Sustainable Marine Product Consumption: Understanding the Impact of Food-Related Lifestyles and Social Influences on Attitudes" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072890

APA StyleAn, S., & Choi, J. (2025). Fostering Sustainable Marine Product Consumption: Understanding the Impact of Food-Related Lifestyles and Social Influences on Attitudes. Sustainability, 17(7), 2890. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072890