From Resistance to Acceptance: The Role of NIMBY Phenomena in Sustainable Urban Development and Tourism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Stakeholders

- (1)

- Regulators: national, local, and international authorities that issue permits and control the individual construction processes.

- (2)

- Stakeholders, which represent interested groups, citizens, etc.: These can be organized groups or groups of citizens who are affected by the construction project during the construction or operation process or at the end of the project; in some cases, such public groups can increase the influence on the progress of the project or even achieve a halt to the project.

- (3)

- Project managers: They lead the project and are involved in the implementation of the project; project managers vary from phase to phase, depending on the specialization of each phase of the project.

- What is their financial or emotional stake in the outcome of project manager work? Is it positive or negative?

- How will the project manager motivate most stakeholders to support the project?

- What information do the stakeholders want to receive about the project?

- How can a project manager communicate between project sponsors and stakeholders best?

- What is the current opinion of stakeholders about project manager work and the professionalism of the project developers? Is it based on good information?

- What and who influences stakeholders’ opinions in general, and what influences their opinions of the project developers?

- If it is likely that the stakeholders will accept the project, what is the key point of the project that will lead to a positive outcome?

- If it is likely that the project will not be accepted by the stakeholders, what strategy can be used to reassure the opposing stakeholders? Is it possible to find a person who can influence the stakeholders and convince them of the usefulness of the project?

3. Materials and Methods

- (1)

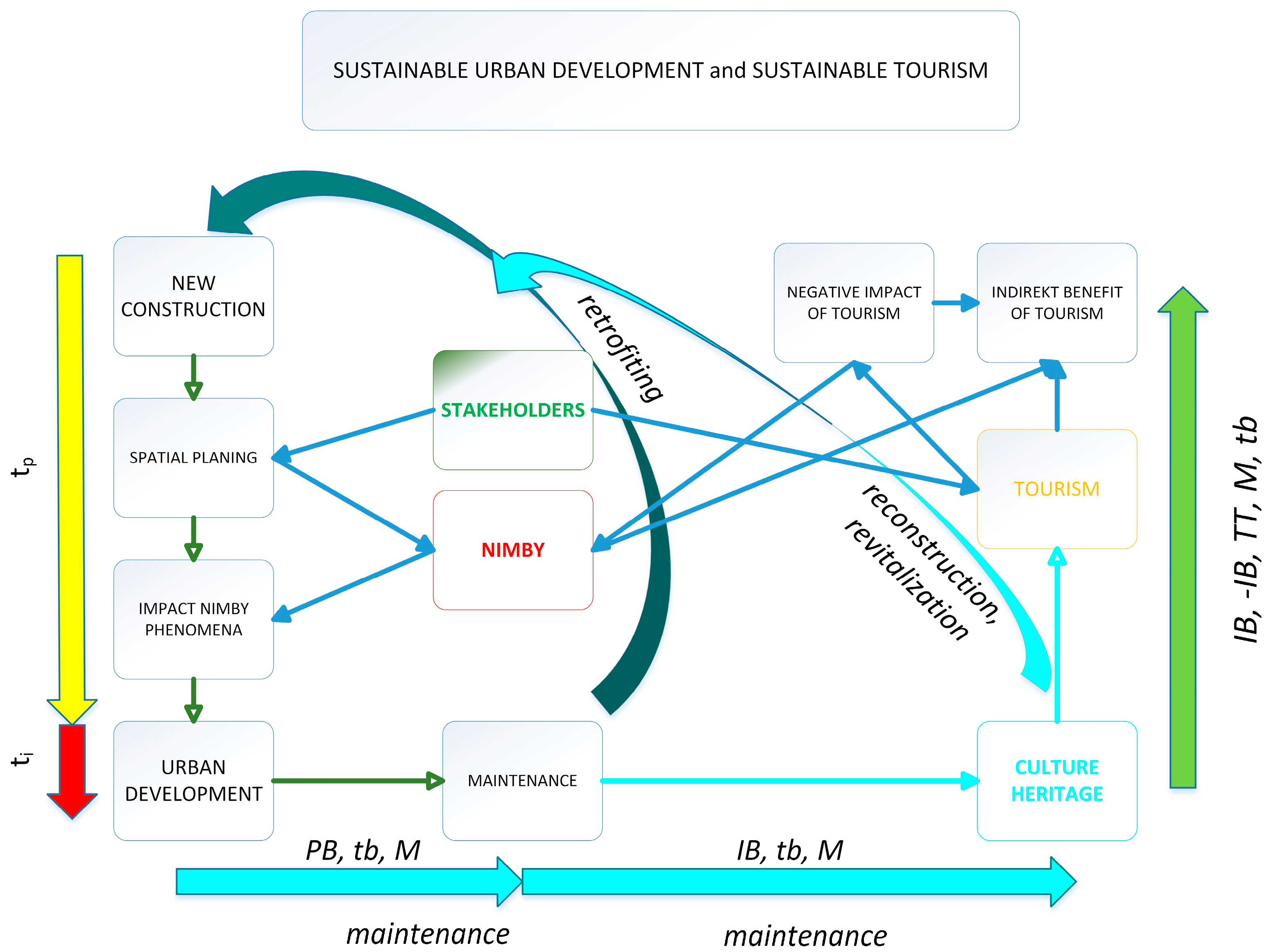

- To analyze the impact of the NIMBY phenomenon on project preparation time (tp) and benefit realization time (tb) in urban and tourism-related developments.

- (2)

- To explore the dynamics of stakeholder interactions in sustainable urban planning.

- (3)

- To investigate the relationship between new construction investments and maintenance costs for sustainable and attractive urban development.

- (4)

- To examine the role of positive indirect revenue generated by the built environment and cultural heritage in relation to tourism.

- (5)

- To evaluate the negative impacts of tourism in relation to the tourist tax.

4. Project Phases and NIMBY Phenomena

4.1. Project Phases

- The conceptual phase;

- The planning (and development) or preliminary design phase;

- The detail design phase;

- The construction phase;

- Start-up and turnover.

- It helps to ensure the safety of occupants and visitors;

- Building maintenance can help extend the life of a building;

- The value of the property is maintained or even increased.

4.2. NIMBY Examples on the Field of Land Use Changes

- (1)

- (2)

- From 2009 to 2018, the project Second track faced strong resistance from residents and environmentalists [97] who raised concerns about its impact on the natural environment, particularly the karst landscape. The issue became a subject of referendums and legal disputes.

- (3)

- (4)

- During the 1990s, plans to expand the airport in Postojna were halted due to protests from residents concerned about the destruction of the natural environment, particularly the sensitive karst terrain.

- (5)

- In 2017, residents opposed the proposal to establish a memorial park at the Former Refugee Reception Center in Jelšane, arguing that the area could be better utilized for other purposes.

4.3. NIMBY Examples in the Field of Tourism

- Jobs and household income;

- Revitalization of city centers;

- Tourism in heritage sites;

- Real estate value;

- Small business incubators.

- Import substitution—the aim is to produce locally.

- Compatibility with modernization—use of modern methods, development, and modernization.

- Diversity of target areas—urban centers or rural villages.

- Not just zero return—all cities have historic buildings.

- Spatial development—distribution of projects across the country.

- Projects of different sizes—larger and smaller.

- Non-cyclicality—provides some stability for the local economy.

- Gradual change—continuity that is not dependent on the current political situation.

- Product diversity—different and unique projects.

- Mass tourism can contribute to the revitalization of city centers.

- Cultural heritage generates economic benefits through increased tourism [17], as visitors to historical sites tend to stay longer, visit more locations, and spend more money on the local economy.

- Restoration works and the promotion of cultural heritage directly employ thousands of people across Europe and indirectly create even more jobs [49].

- Preservation of cultural heritage ensures environmental, cultural, and economic sustainability, aligning with the principles of sustainable development.

4.4. Parameters in NIMBY Phenomena

- tp (preparation time): the time required to prepare the project. This phase includes various factors such as the investor’s capital, the professional qualifications of the project developers, stakeholders, government personnel, city or state agencies, and the NIMBY phenomenon.

- ti (construction time): the time required to construct the project. This phase usually proceeds quickly and easily, as all prior dilemmas have been resolved.

- tb (benefit time): the time during which the project provides benefits. This phase is closely connected with the building’s lifespan, the durability of some building materials, and the condition of the building. It also depends on sustainable design and investment in the building’s maintenance (MM).

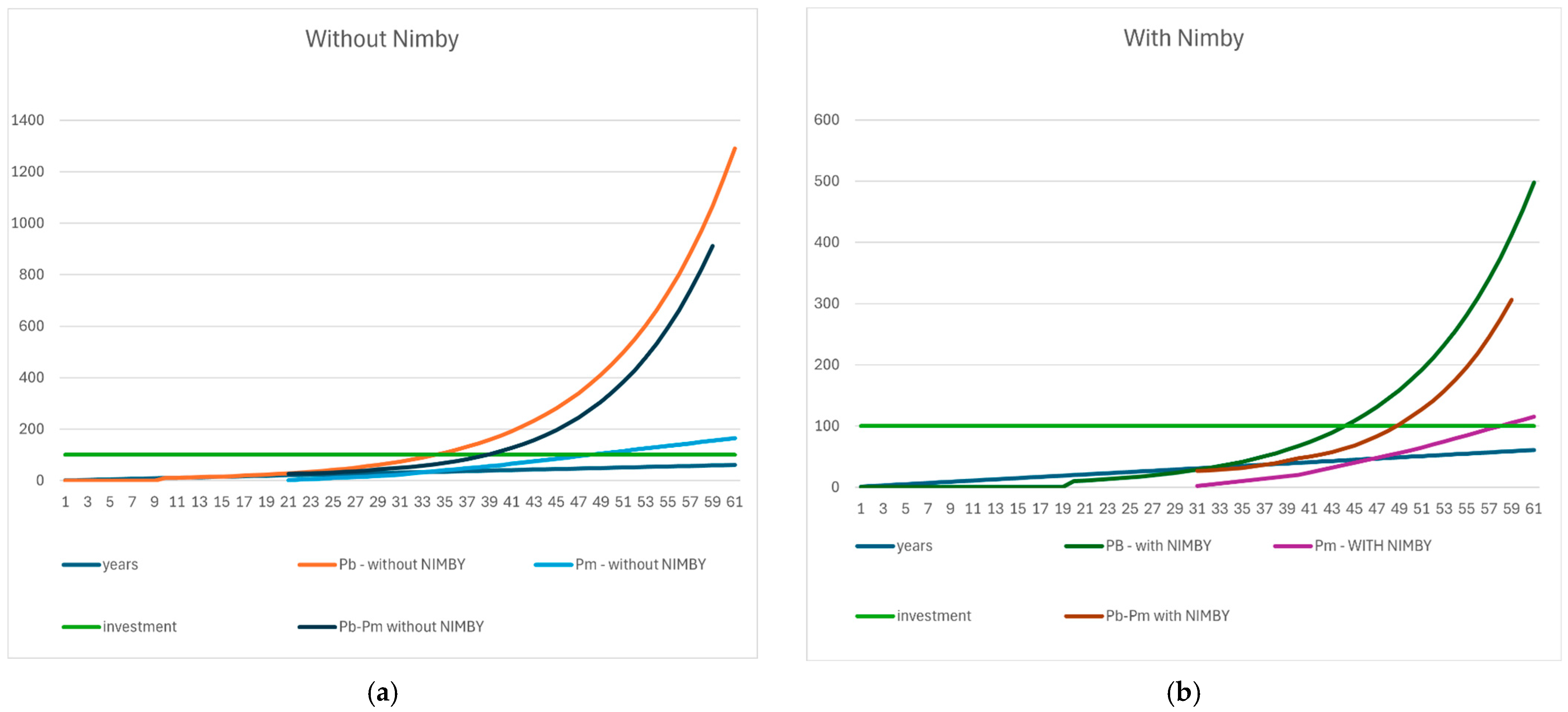

- PB (project benefit): the benefits that the project provides over time. This can include financial benefits, improvements in quality of life, environmental benefits, etc.

- IB (indirect benefit): the benefits that cultural heritage brings. This can include an increase in property value, job creation, etc.

- M (maintenance): the maintenance of the building. This includes all activities necessary to keep the building in good condition, such as repairs, renovations, cleaning, and other maintenance activities.

- −IB (negative economic cost): the negative financial impact of an individual tourist, including costs for waste management, water consumption, carbon emissions, noise reduction, and environmental restoration.

- Pollution: The average tourist generates approximately 1 kg of waste per day. Waste management costs can vary, but they can be around 0.50 EUR per kg.

- Water consumption: A tourist consumes approximately 300 L of water per day. Water costs are approximately 2 EUR per 1000 L, which means about 0.60 EUR per day.

- Carbon footprint: The average tourist contributes approximately 0.5 kg of CO2 per kilometer traveled. The cost to offset CO2 emissions is approximately 0.02 EUR per kg of CO2, which means about 0.01 EUR per kilometer.

- Noise: Noise reduction costs can vary, but they can be around 0.10 EUR per tourist day.

- Erosion and environmental degradation: The costs of restoring natural landmarks and protecting the environment can be around 1 EUR per tourist day.

- Infrastructure Financing: Funds are used to maintain and improve city infrastructure, such as roads, public transport, and utilities.

- Environmental Protection: Part of the funds can be allocated to environmental protection projects, such as cleaning beaches, parks, and other natural landmarks.

- Cultural Heritage Support: The tax helps finance the maintenance and restoration of historical and cultural landmarks popular with tourists.

- Tourism Management: Funds can be used to manage tourist flows and reduce the negative impacts of mass tourism.

- Local Development: Part of the funds can be allocated to support local communities and improve residents’ quality of life.

5. Results

- Tourist tax covers at least the costs of the negative impact of tourists on the city, for example, at least 2.5 EUR per day.

- Tourist tax is higher in the high season, moderate in the mid-season, and lower in the low season.

- Tourist tax is higher in higher-rated hotels and lower in lower-rated categories.

- This causes a reduction in tourist pressure in the main seasons and a redistribution over a longer period, as well as a shift from tourist cities to other destinations in the region.

6. Discussion

- (1)

- Participants in spatial use projects can resist by extending the project preparation time (tp) beyond any reasonable measure, even when a benefit is expected for the public good (e.g., investment in the construction of green energy sources).

- (2)

- Participants can resist if their living space or habits are interfered with, even if the indirect benefits (IB) are positive (e.g., tourism).

- (3)

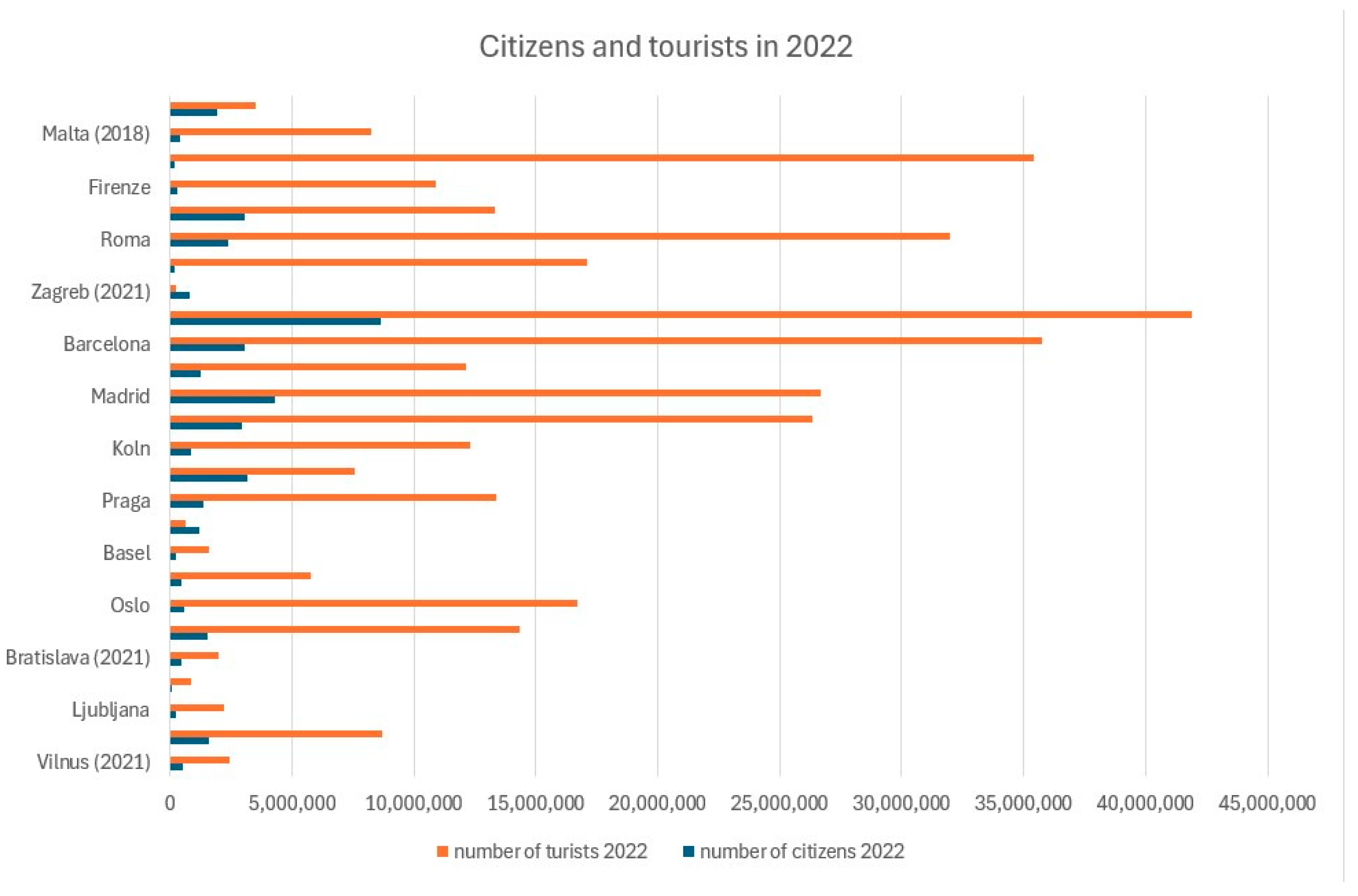

- There is a correlation between the number of tourists and the number of residents when the NIMBY phenomenon occurs.

- (4)

- Some cities where the NIMBY phenomenon has occurred do not have an established mechanism (e.g., tourist tax) to mitigate the negative consequences of tourism (e.g., Valencia) or the mechanism is insufficient (e.g., Dubrovnik).

- (1)

- We may avoid the NIMBY phenomena entirely due to increasingly powerful centralist governments with capital and indifference to democracy, global warming, and sustainable spatial development, where the population will become victims of capital and global centralist leaders.

- (2)

- We may not avoid NIMBY phenomena entirely, as there will still be selfish individuals driven by profit.

- (3)

- NIMBY phenomena may disappear due to a higher level of awareness for proactive cooperation and sustainable use of all resources, including space and sustainable tourism.

7. Conclusions

- Stakeholder Engagement is Essential: Projects with high levels of public participation tend to have shorter preparation times and smoother implementation. Governments and investors must prioritize transparent dialogue and integrate community feedback throughout all project phases.

- Sustainability Requires Long-Term Vision: Sustainable projects must prioritize long-term benefits (tb) over short-term economic gains, ensuring environmental preservation and cultural integrity. The most effective projects employ strategies that accommodate future growth and adaptive reuse of space.

- Heritage Sites Demand Special Consideration: While historic sites boost tourism and economic growth, their commercialization must be carefully managed to avoid negative societal impacts. Conservation strategies must be balanced with the need for modernization to keep these sites relevant and well-maintained.

- Adaptive Planning Enhances Project Success: Flexible planning frameworks that incorporate community input and evolving stakeholder needs lead to more resilient urban development. Cities must adopt policies that allow for periodic review and adaptation to changing environmental and social conditions.

- Strategic Communication Reduces Opposition: Clear, transparent communication and proactive conflict resolution can shift public perception from resistance to acceptance. Misinformation and lack of awareness often contribute to opposition; therefore, educational campaigns and stakeholder forums should be implemented to build trust.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NIMBY | Not in My Backyard |

| YIMBY | Yes in My Backyard |

| tp | Preparation time |

| ti | Construction time |

| tb | Benefit time |

| PB | Project benefit |

| IB | Indirect benefit |

| −IB | Negative economic cost |

| I | Investment |

| M | Maintenance |

| TT | Tourist tax |

| NIMM | Not in My Neighborhood |

| NIABY | Not in Anyone’s Backyard |

| NAMBI | Not Against My Business or Industry |

| BANANA | Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything |

| PIBBY | Place in Blacks’ Backyard |

| SOBBY/YBNH | Some Other Bugger’s Backyard/Yes, But Not Here |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| CHT | Cultural Heritage Tourism |

References

- NIMBY. Merriam-Webster Dictonary; Merriam-Webster: Springfield, MA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, E. No One Wants Backyard Nuclear Dump; Daily Press: Hanover, VA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Semuels, A. From “Not in My Backyard” to “Yes in My Backyard”. The Atlantic, 5 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, A.L.; Porth, J.M.; Wu, Z.; Boulton, M.L.; Finlay, J.M.; Kobayashi, L.C. Vaccine Hesitancy During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis of Middle-Aged and Older US Adults. J. Community Health 2022, 47, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Weerd, W.; Timmermans, D.R.M.; Beaujean, D.J.M.A.; Oudhoff, J.; Van Steenbergen, J.E. Monitoring the level of government trust, risk perception and intention of the general public to adopt protective measures during the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, J.; Forte, G. The economic impact of Brexit-induced reductions in migration. Oxford Rev. Econ. Policy 2017, 33, S31–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights. Memorandum on the Stigmatisation of LGBTI People in Poland (CommDH(2020)27); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kappner, K.; Letmathe, P.; Weidinger, P. Causes and effects of the German energy transition in the context of environmental, societal, political, technological, and economic developments. Energy. Sustain. Soc. 2023, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, D. Populism and Carbon Tax Justice: The Yellow Vest Movement in France. Soc. Probl. 2023, 70, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB Editor The Olympic Bid “Nimby” Factor. Available online: https://gamesbids.com/eng/other-news/the-olympic-bid-nimby-factor-2/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Almeida, D.; Shmarko, K.; Lomas, E. The ethics of facial recognition technologies, surveillance, and accountability in an age of artificial intelligence: A comparative analysis of US, EU, and UK regulatory frameworks. AI Ethics 2022, 2, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuletić, D.; Ostoić, S.K.; Báliková, K.; Avdibegović, M.; Potočki, K.; Malovrh, Š.P.; Posavec, S.; Stojnić, S.; Paletto, A. Stakeholders’ opinions towards water-related forests ecosystem services in selected southeast European countries (Federation of bosnia and herzegovina, croatia, Slovenia and Serbia). Sustainability 2021, 13, 12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Bonnefous, A.M. Stakeholder management and sustainability strategies in the French nuclear industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, E.C. Meet the YIMBYs, Seattleites in Support of Housing Density. Seattle Magazine. 2016. Available online: https://seattlemag.com/seattle-living/meet-yimbys-seattleites-support-housing-density/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Stephens, J. “YIMBY” Movement Heats Up in Boulder; Next City: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rypkema, D.D. The Economic of Historic Preservation, 4th ed.; National Trust for Historic Preservation: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vuk, V. Slava Srednjeveškega Obzidja. VECER, 28 May 2006; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Burgen, S. Barcelona Craks Down on Turist Numbers with Accommodation Law. The Guardian. 2017. Available online: https://igcat.org/barcelona-cracks-down-on-tourist-numbers-with-accommodation-law/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Sivka, R. Ljubljančane ob Pamet Spravljajo Turisti: “Okna Sploh ne Moreš Odpreti, ne da bi te Fotografiralo 30 Ljudi”. 2024. Available online: https://www.metropolitan.si/novice/slovenija/nadlezni-turisti-pobude-mescanov-ljubljana/ (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Yoshida, M.; Kato, H. Housing Affordability Risk and Tourism Gentrification in Kyoto City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogorelec, B. Komuniciranje z Javnostjo, Priročnik za Urbaniste; Urbanistični inštitut Republike Slovenije: Ljubljana, Slovenije, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. Construction Extension to The PMBOK Guide, 3rd ed.; Project Management Institution: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dvornik, P.D.; Drozg, V.; Kos, G.J. Square and park in the centre of the city—Diametric contrast or unique renovation of Slomšek Square in Maribor as an experiment to prove diametric contrast of park and square. In Zelenilo u gradu Zagreb; Akademija Hrvatskih Znanosti i Umijetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory; Revised edition (March 17, 1969); Fonduations Development Aplications; George Braziller Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1979; p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- Veselič, M.; Železnik, N. Izkušnje pri Umeščanju Odlagališča NSRAO v Prostor 2006, 18. Available online: https://arhiv.djs.si/alfa/index_files/predavanja.htm (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Kos, G.J. Nasprotja med Družbenimi in Prostorskimi Koncepti, Vrednotami ter Interesi v Okviru Polemike o Preureditvi Slomškovega trga v Mariboru v Letih 1995–2000. 2001. Available online: https://likodej.si/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/JKG_SlomSkov_trg_polemika_seminarska_naloga_2001_za_www.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Alberta. Alberta Environmental Protection. Environment Views. Environ. Alberta 1980, 4. Available online: https://archive.org/details/enviroviews2n6/page/4/mode/2up (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Annesi, N.; Battaglia, M.; Frey, M. Stakeholder engagement by an Italian water utility company: Insight from participant observation of dialogism. Util. Policy 2021, 72, 101270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, G.; Testa, M.; Lepore, L. How Is the Utilities Sector Contributing to Building a Sustainable Future? A Systematic Literature Review of Sustainability Practices. Sustainability 2024, 16, 374. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, S.; Silvestre, B.S. Managing stakeholder relations when developing sustainable business models: The case of the Brazilian energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhir, V.; Muraleedharan, V.R.; Srinivasan, G. Integrated Solid Waste Management in Urban India: A Critical Operational Research Framework. Pergamon Socio Econ. Plann. Sci. 1996, 30, 163–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Ahmed, S.; Punthakey, J.F.; Dars, G.H.; Ejaz, M.S.; Qureshi, A.L.; Mitchell, M. Statistical Analysis of Climate Trends and Impacts on Groundwater Sustainability in the Lower Indus Basin. Sustainability 2024, 16, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompsom, R. Stakeholder Analysis: Winning Support for Your Projects; MindTools Corp.: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Perc, M.; Grigolini, P. Collective behavior and evolutionary games—An introduction. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1306.2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbes, T. Leviathan, 2nd ed.; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1962; p. 1651. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Marwell, G.; Ames, R. Economist free ride, does anyone else? J. Public Econ. 1981, 15, 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, J.; Rand, D.; Zeckhauser, R. The online laboratory: Conducting experiments in a real labor market. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 399–425. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, D.; Greene, J.; Nowak, M. Spontaneous giving and calculated greed. Nature 2012, 489, 427–430. [Google Scholar]

- Murks-Bašič, A.; Perc, M. Podnebna kooperacija v igri Zapornikove dileme. Naše Gospod. 2011, 5–6, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.D. Exercise rehabilitation for cardiac patients: A beneficial but underused therapy. Physician Sportsmed. 2001, 29, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.D. Not in My Neighborhood. Time. 1988. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20080725095112/http:/www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,966534,00.html (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Pietila, A. Bigotry Shaped a Great Baltimore City: Antero Pietila. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2011, 31, 358–359. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, R. From NIMBYs To DUDEs: The Wacky World of Plannerese. 2005. Available online: https://www.planetizen.com/node/152 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Stewart, J.B. Book Review: Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Rev. Black Polit. Econ. 1991, 20, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R.D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 2013436106. [Google Scholar]

- Gravano, A. ¿Vecinos o ciudadanos? El fenómeno Nimby: Participación social desde la facilitación organizacional. Rev. Antropol. 2011, 54, 191–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nypan, T. Cultural Heritage Monuments and Historic Buildings as Value Generators in a Post-Industrial Economy; With Emphasis on Exploring the Role of the Sector as Economic Driver; 2003. Available online: https://mapa.valpo.net/sites/default/files/repositorio-documentos/nypan_ch_und_tourismus.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Rypkema, D.D. Feasibility Assessment Manual for Reusing Historic Buildings; National Trust for Historic Preservation: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Loncarić, R. Organization of Performence of Construction Project; Croation Society of Civil Engineers: Zagreb, Croatia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, D.D. Design and Planning of Engineering Systems; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kast, F.E.; Rosenzweig, J.E. Organization and Management, A System Approach; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- What is the Life Span of a Building. Available online: https://theconstructor.org/question/what-is-the-life-span-of-a-building/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- CCUK Composites Construction, UK. What is the Design Life of Buildings? CCUK Composites Construction UK: Hessle, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, J. 5 Factors That Determine a Building’s Lifespan; Strata Global Community Managazines Development Consult: Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.; Qu, J.; Maraseni, T.N.; Wu, J.; Xu, L.; Fan, Y. Spatial and temporal variations of embodied carbon emissions in China’s infrastructure. Sustainability 2019, 11, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, A. 5 Benefits of Building Maintenance. Small Business Bonfire. 2023. Available online: https://smallbusinessbonfire.com/benefits-of-building-maintenance/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- D’Alor, E.C.M. 10 Superb Benefits of Building Maintenance/Facility Management Service Compiled by Maison d’Alor. Linkedin. 2018. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/10-superb-benefits-building-maintenance-facility-service-d-alor/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Božičnik, A. Študija Možnosti Ponudbe Visokega Turizma v Objektih Kulturne Dediščine Slovenije; Ministrstvo za Kulturo: Ljubljana, Slovenije, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Misiura, S. Heritage Marketing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage, E. English Heritage, 2014. Available online: https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/ (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- Fantozzi, J. 35 Abandoned Places in USA and the History Behind Them. 2018. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/abandoned-places-usa-2018-1 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Galwin, A. News. OC Weekly. Internet Arch. Wayback Machibe. 2014. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20160130210045/http://digitalissue.ocweekly.com/article/News/1800742/223650/article.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Wintour, P. Fracking Will Meet Resistance From Southern Nimbys, Minister Warns. The Guardian. 2013. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/aug/04/fracking-resistance-southern-nimbys-minister (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Marcotte, A. What North Dakota and Mississippi Reveal About Anti-Choice NIMBYism and Hypocrisy. Rewire News 2013, 8, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, J. Radioactive Nimby: No One Wants Nuclear Waste. New York Times. 2007. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/07/business/businessspecial3/07nuke.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Common, M. Trident Removal Is a Nimby Position. The Herald. 2014. Available online: https://www.heraldscotland.com/opinion/13176440.trident-removal-nimby-position/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Holehouse, M. Boris Johnson: Nimbies Pretend to Care About Architecture to Block Developments. 2014. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/london-mayor-election/mayor-of-london/10984944/Boris-Johnson-Nimbies-pretend-to-care-about-architecture-to-block-developments.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- News, C.B.C. Chester Approves Nova Scotia’s Largest Wind Farm 2013. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/chester-approves-nova-scotia-s-largest-wind-farm-1.1332473 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Quinlan, P. Survey Supports Turbines, FPL Says. Palm Beach Post News. 2008. Available online: https://www.wind-watch.org/news/2008/04/03/wind-farm-wont-please-everyone-epuron/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- CTV Atlantic, Negative Feedback Towards New Development in N.S. Community 2013. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/atlantic/article/negative-feedback-towards-new-development-in-ns-community/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Barnes, K. No Heroes in My Backyard. Sutton Croydon Guardian. 2007. Available online: https://www.yourlocalguardian.co.uk/news/1559722.no-heroes-in-my-backyard/ (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Dineen, J.K. NIMBYs Are Back: S.F. Builders Face Growing Backlash. San Fr. Bus. Times, 2013. Available online: https://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/blog/2013/07/nimbys-are-back-sf-builders-face.html (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Sankin, A. 8 Washington Luxury Waterfront Condo Development Project Vote Likely to Make It Onto November Ballot (PHOTOS). Huffpost. 2012. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/8-washington_n_1690575?ec_carp=4292722873799104527&guccounter=1 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Rosen, H.M.; Rosen, D.H. But Not Next Door, 1st, ed.; Obolensky, I., Ed.; Obolensky Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1962; ISBN 0839210078. [Google Scholar]

- Foot, T. EXCLUSIVE: HS2 Bosses Set to Abandon Camden Town “Link” Stage of High Speed Rail Project. Independent London Newspaper CamdenNewJournal. 2014. Available online: https://www.camdennewjournal.co.uk/article/exclusive-hs2-bosses-set-abandon-camden-town-link-stage-high-speed-rail-project (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Gray, M. Britain: Third Heathrow Runway Approved Despite Opposition. CNN. 2009. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2009/BUSINESS/01/15/heathrow.third.runway/index.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- News, B.B.C. Heathrow Runway Plans Scrapped by New Government. BBC News. 2010. Available online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/london/8678282.stm (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Povoledo, E. Italy Divided Over Rail Line Meant to Unite. CHIOMONTE Journal. 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/18/world/europe/italy-divided-over-rail-line-meant-to-unite.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- The Narita Airport. Emergency Appeal. An Appeal to Stop Use of the Temporary Runway at Narita Airport Appeal. 2002. Available online: https://www.jca.apc.org/~misatoya/narita/n_s_e.html (accessed on 22 November 2024).

- 710 Freeway Extension Officially Dead, State and City Officials Celebrate and Look to the Future. Pasadena Now. 2018. Available online: https://discoveringpasadena.com/710-controversy (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Sheehan, T. Kings County Opponents of High-Speed Rail Get Their Court Date. Fresno Bee. 2016. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/road-and-rail-transport/9431123/High-speed-train-opponents-granted-court-hearing.html (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Regnier & Associates Inc. State Road 80 Expansion. Wayback Machine. 2009. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20090913005949/http://regnierassociates.com/_webapp_982567/State_Road_80_Expansion (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Lam, A. Drug Expert Quits College Job to Easy Conflict of Interest Worries. South China Morning Post. 2009. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/article/701864/drug-expert-quits-college-job-ease-conflict-interest-worries (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Maries, L. Notes of Consultation on Proposed Expansion of Dundonald Primary School. 2011. Available online: https://merton.moderngov.co.uk/Data/Children%20and%20Young%20People%20Overview%20and%20Scrutiny%20Panel/20110915/Agenda/766.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- CNN. China’s “Nail Houses”: The Homeowners Who Refused to Budge. Obama’s Speech Highlights Rise 3-D Print. 2013. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2015/05/19/asia/gallery/china-nail-houses/index.html (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Varinsky, D. China Refuse to Give in to Developers. 2016. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/what-are-chinese-nail-houses-2016-8 (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- LIRR. MTA Long Island Rail Road, East Side Access and Third Track—Main Line Corridor Improvements. 2008. Available online: https://www.mta.info/project/lirr-main-line-expansion (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Rather, J. Third-Track Project Finds Its Nemesis. The New York Times. 2005. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/10/nyregion/thirdtrack-project-finds-its-nemesis.html (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Petrellese, S.M. Village Meets With LIRR On “Third Track” Project. Garden City News. 2006. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20070112195001/http://www.gcnews.com/news/2006/1215/Front_Page/001.html (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Keane, C. Residents: MTA/LIRR Needs to Get on Right Track. Illustrato News. 2005. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20070927195104/http://www.antonnews.com/illustratednews/2005/06/24/news/ (accessed on 21 November 2024).

- Nardiello, C. Third-Track Plan Isn’t Dead, L.I.R.R. Insists. The New York Times. 2008. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/14/nyregion/nyregionspecial2/14lirrli.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- McLogan, J. LIRR Third Track Project Moving Forward Despite Concerns Of Residents. CBS New York. 2018. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/lirr-third-track-project-concerns/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Heikkila, E.J.; Pizarro, R. Sauthern California and the World; Praeger Publisher: Westport, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Greenpeace Slovenija TEŠ 6: Moratorij na Odločanje, Etično Razsodišče ter Trajnostni Energetski Scenarij kot Bistveni Elementi Katerekoli Koalicijske Pogodbe. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/slovenia/sporocilo-za-javnost/1297/tes-6-moratorij-na-odlocanje-eticno-razsodisce-ter-trajnostni-energetski-scenarij-kot-bistveni-elementi-katerekoli-koalicijske-pogodbe/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Ekologi Brez Meja Javni Poziv Proti Poroštvu za TEŠ 6. Available online: https://ebm.si/prispevki/javni-poziv-proti-porostvu-za-tes-6 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Vogrin, N.; Atelšek, R. Referendum je Padel, Kovačič Napovedal Novo Pritožbo. Available online: https://siol.net/novice/slovenija/na-referendumu-drugic-o-zakonu-o-drugem-tiru-467258 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Stanković, D. Odlagališče do 2027, Sedež ARAO Nazaj v Krško. Available online: https://dolenjskilist.svet24.si/2024/06/06/289741/novice/posavje/odlagalisce_do_2027_sedez_arao_nazaj_v_krsko/ (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Mestna Občina Krško V Krškem Nasprotujemo Izhodiščem Reševanja Skupnega Odlaganja NSRAO v Vrbini. Available online: https://www.krsko.si/objava/178827 (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Dwyer, L. Tourism development and sustainable well-being: A Beyond GDP perspective. J. Sustain. Tour. 2023, 31, 2399–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živkovič, G. Avstrija Živi od Kulturne Dediščine [Intervju] 2014. Available online: https://old.delo.si/kultura/razno/milan-sagadin-arheologija-odkriva-duso-pokrajine.html (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Hohmamm, J. Internationales Stadteforum Graz. ISG Magazine, 2000, 32. Available online: https://staedteforum.at/resume-2020/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Greg, D.; Parker, K. Has Tourism Killed Dubrovnik? We Visited During the Busiest Month of the Year to Find Out. The Telegram. 2018. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/croatia/dubrovnik/articles/dubrovnik-tourism-crowded/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Burgen, S. Tourists Go Home, Refugees Welcome’: Why Barcelona Chose Migrants Over Visitors. The Guardian. 2018. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/jun/25/tourists-go-home-refugees-welcome-why-barcelona-chose-migrants-over-visitors (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Rogulj, D. Is Split-Dalmatia County on Verge of Tourism Collapse? An Expert Opinion. Total Croatia News. 2018. Available online: https://total-croatia-news.com/news/travel/split-10/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Eurostat. EUROSTAT. EC Eur. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=City_statistics_-_tourism (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- citizens EUROSTAT EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/urb_cpop1/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Tamma, P. Italy’s High-Speed Railway Dilemma. POLITICO. 2018. Available online: https://www.politico.eu/article/matteo-salvini-danilo-toninelli-5stars-league-italy-high-speed-railway-dilemma/ (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Berger, P. MTA Awards $1.8 Billion Contract to Expand Long Island Rail Road. The Wall Street Journal. 2017. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/mta-awards-1-8-billion-contract-to-expand-long-island-rail-road-1513208765 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Andrews, W. Sanrizuka: The Struggle to Stop Narita Airport. Throw Out Your Books. 2014. Available online: https://throwoutyourbooks.wordpress.com/2014/02/11/narita-airport-protest-movement-sanrizuka/ (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- ZEU, d.o.o. Primerjalna Študija Variantnih Rešitev Poteka Daljnovoda 2 × 400 kV Cirkovce—Pince. 2005. Available online: https://www.uradni-list.si/glasilo-uradni-list-rs/vsebina/2012-01-2334 (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Vahtarić, S. Lokalno partnerstvo Brežice v postopku iskanja lokacije za odlagališče NSRAO. Diploma Thesis, Univerza v Ljubljani, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meininger Hotels MEININGER Hotel Zürich Greencity. Available online: https://help-center.meininger-hotels.com/en/support/solutions/articles/79000144063-city-tax-information-for-meininger-hotel-zürich-greencity (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Forgotten Lands, Places and Transit. Ghost Towns, Abandoned Places and Historic Sites. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1UUfwmW5YntQiVznItYrXwHYn1D9eGkgU&hl=en_US&ll=34.92090202187946%2C-89.46123010138193&z=4 (accessed on 8 February 2024).

- Christopher, M. Abandoned America: An Autopsy of the American Dream. Available online: https://www.abandonedamerica.us/ (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Roblek, V.; Drpić, D.; Meško, M.; Milojica, V. Evolution of sustainable tourism concepts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Martínez, D.; Seguí-Pons, J.M.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Conceptual Framework and Prospective Analysis of EU Tourism Data Spaces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beton, K. Analiza Vplivov Turizma. Available online: https://www.radolca.si/media/slo GREEN/ANALIZA vplivov turizma.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Ljubljana Turistična Taksa v Ljubljani. Available online: https://www.visitljubljana.com/sl/obiskovalci/informacije/turisticna-taksa-v-ljubljani/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- RH Dubrovačko-Neretvanska Županija Upravni Odjel za Poduzetništvo Turizam i More Odluka o Visini Turističke Pristojbe za 2024. Godinu; 2022. Available online: https://www.dnz.hr/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/Odluka-o-visini-turistiuke-pristojbe-za-2024.-godinu.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Area Economia E Finanza; Settore Tributi—Servizio Imposte Locali E Riscossione. Mposta Di Soggiorno Tariffe in Vigore dal 01.07.2021 Strutture Classificate AI Sensi Della L.R.V. 11/2013; 2021. Available online: https://www1.finanze.gov.it/finanze2/dipartimentopolitichefiscali/fiscalitalocale/nuova_at/download_lib.php?key=0900f230805f66e8&nome=350228_CIMUNIC-09mi24d045AM.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Institut Municipal d’Hisenda de Barcelona Tourist Establishments Tax. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/hisenda/en/procedures-payments/tourist-establishments-tax?profile=1 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Norwegian Holidays Tourist Fee. Available online: https://www.norwegianholidays.com/eu/tourist-fee (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Trippz Tourist Tax Zurich 2025. Available online: https://trippz.com/tourist-tax/switzerland-zurich (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- expats_cz Prague 1 Aims to Significantly Increase the City’s Tourist Tax. Available online: https://www.expats.cz/czech-news/article/prague-1-aims-to-significantly-increase-city-s-tourist-tax (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Immofy Travelling & Costa Blanca Region, Rejection of the Tourist Tax in the Valencian Community12 March. Available online: https://blog.immofy.eu/en/rejection-of-the-tourist-tax-in-the-valencian-community (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Hotellagriffe.com Information On City Tax Regulation. Available online: https://www.hotellagriffe.com/public/TASSA%20DI%20SOGGIORNO/Informativa_Contributo_di_Soggiorno_ENG_Agosto_2024.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Commune di Firenze. Imposta di Soggiorno. Tourist Tax, 2025. Available online: https://www.feelflorence.it/sites/www.feelflorence.it/files/2025-02/TOURIST%20TAX%202025.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Minoja, M.; Romano, G. Managing intellectual capital for sustainability: Evidence from a Re-municipalized, publicly owned waste management firm. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A. Corp Soc Responsibility Env-2004-Schaefer-Corporate sustainability integrating environmental and social concerns. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2004, 11, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Galindo, G.A.; Casella, E.; Mejía-Rentería, J.C.; Rovere, A. Habitat mapping of remote coasts: Evaluating the usefulness of lightweight unmanned aerial vehicles for conservation and monitoring. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 239, 108282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Sustainable performance index for tourism policy development. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caust, J.; Vecco, M. Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, A.; Đurović, G.; Hanscom, L.; Knežević, J. Think globally, act locally: Implementing the sustainable development goals in Montenegro. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Timothy, D.J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: Cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2020, 18, 386–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Fagnoni, E. Managing World Heritage Site stakeholders: A grounded theory paradigm model approach. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construction Material | Life Span (Years) |

|---|---|

| Historical structures | 500–1000 |

| Steel structures | 100–150 |

| Steel bridges | 120 |

| Concrete structures and buildings | 100 |

| Other commercial or private buildings | 60–80 |

| Brick masonry | 100 |

| Glass | 50 |

| Marble/granite | 75 |

| Ceramic tiles | 75 |

| Plaster | 40 |

| GI pipes | 30 |

| Faktorji | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Ljubljana | Dubrovnik | Venice | Barcelona | Oslo | Zurich | Prague | Valencia | Rome | Florence |

| 2013 | 4.75 | 29.27 | 11.15 | 5.19 | 3.57 | 4.25 | 3.92 | 3.13 | 3.31 | 5.79 |

| 2014 | 4.75 | 30.95 | 11.20 | 5.25 | 3.71 | 4.50 | 4.00 | 3.38 | 3.47 | 6.05 |

| 2015 | 5.08 | 35.71 | 11.67 | 5.56 | 3.86 | 4.75 | 4.15 | 3.63 | 3.63 | 6.32 |

| 2016 | 5.42 | 38.10 | 12.11 | 5.69 | 4.14 | 5.00 | 4.31 | 3.75 | 3.79 | 6.58 |

| 2017 | 5.76 | 40.48 | 12.99 | 5.75 | 4.43 | 5.25 | 4.46 | 4.00 | 4.11 | 7.11 |

| 2018 | 5.76 | 42.86 | 13.83 | 5.94 | 4.71 | 5.50 | 4.62 | 4.25 | 4.42 | 7.37 |

| 2019 | 6.10 | 45.24 | 15.02 | 6.06 | 5.00 | 5.75 | 4.77 | 4.38 | 4.73 | 7.63 |

| 2020 | 3.05 | 9.76 | 6.54 | 2.81 | 1.86 | 2.25 | 2.31 | 1.88 | 1.50 | 3.16 |

| 2021 | 3.73 | 19.51 | 8.08 | 3.75 | 2.57 | 3.00 | 2.69 | 2.50 | 2.60 | 3.95 |

| 2022 | 4.41 | 26.83 | 12.69 | 5.63 | 3.14 | 3.75 | 4.08 | 3.63 | 12.11 | 6.05 |

| 2023 | 4.75 | 31.71 | 13.08 | 5.94 | 3.57 | 4.50 | 4.23 | 3.75 | 12.24 | 6.32 |

| average | 4.87 | 31.86 | 11.67 | 5.23 | 3.69 | 4.41 | 3.96 | 3.48 | 5.08 | 6.03 |

| Project Phases with Time Factors | Construction of a Building | Historic Building (Reconstruction, Revitalization) | Cultural Heritage (Conversion or Renovation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept phase | tp | tp | |

| Planning (and development) or preliminary design phase | tp | tp | |

| Detailed design phase | tp | tp | |

| Construction phase | ti | ti | |

| Commissioning (start-up) | tb, PB | tb, IB (PB) | |

| Maintenance and turnover | M | IB | tb, M, IB, −IB |

| Country | Year | tp (Years) | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium [25] | 1984–1994 | 10 | Unsuccessful application of the technocratic approach; this led to the abandonment of the process. Between 1998 and 2006, the investor entered partnerships and decided on the location of the landfill without compensating residents. The citizens worked out a comprehensive project. |

| United Kingdom [25] | 1976–1997 | 21 | The technical conditions for finding a landfill were used unsuccessfully. The population rejected the landfill three times. After 1997, the government adopted a new approach that allowed citizens to participate in the search for a new landfill. |

| Italy [108] | 1991–2019 | 28 | Italian high-speed rail between Turin and Lyon |

| USA [89,109] | 2005–2017 | 12 | Third track on main line from Floral Park Station to Hicksville Station |

| Japan [110] | 1960–1980 | 20 | Narita International Airport |

| USA [81] | 1958–2018 | 60 | The 710 Freeway Corridor |

| City | Tourist Tax |

|---|---|

| Ljubljana [119] | 3.13 (2.5 TT + 25% × 2.5 TT = promotion tax) |

| Dubrovnik [120] | 2 EUR |

| Venice [121] | 1.5–5 EUR |

| Barcelona [122] | 3.25 EUR |

| Oslo [123] | under consideration |

| Zurich [113,124] | 2.5 CHF |

| Prague [125] | 0.82–1.97 EUR |

| Valencia [126] | under consideration |

| Rome [127] | 4–10 EUR |

| Florence [128] | 3.5–8 EUR |

| Munchen [113] | 0 EUR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dvornik Perhavec, D.; Kamnik, R. From Resistance to Acceptance: The Role of NIMBY Phenomena in Sustainable Urban Development and Tourism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072864

Dvornik Perhavec D, Kamnik R. From Resistance to Acceptance: The Role of NIMBY Phenomena in Sustainable Urban Development and Tourism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072864

Chicago/Turabian StyleDvornik Perhavec, Daniela, and Rok Kamnik. 2025. "From Resistance to Acceptance: The Role of NIMBY Phenomena in Sustainable Urban Development and Tourism" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072864

APA StyleDvornik Perhavec, D., & Kamnik, R. (2025). From Resistance to Acceptance: The Role of NIMBY Phenomena in Sustainable Urban Development and Tourism. Sustainability, 17(7), 2864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17072864