Abstract

As a staple food and a key component of livestock feed, the growing demand for maize in Indonesia has spurred the expansion of hybrid maize cultivation. However, despite advancements in seed technology and government initiatives to boost maize production, farmers in rural areas continue to face obstacles in accessing high-quality seeds. This study explores the influence of the marketing mix—encompassing product, price, promotion, and distribution—alongside personal factors on farmers’ purchasing decisions for hybrid maize seeds in Soppeng District. Utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM) and survey data from 100 respondents, the findings indicate that product quality and price are the most critical determinants, with farmers prioritizing seed performance and affordability. Distribution also plays a vital role in rural areas, ensuring that farmers can readily access high-quality seeds. At the same time, personal factors such as farming experience and income significantly shape purchasing behavior. Notably, promotional efforts appear to have a limited impact, suggesting that traditional marketing approaches may not be the most effective in this context. Seed companies should focus on product development, refine pricing strategies, and strengthen distribution networks to enhance market penetration. In parallel, policymakers can facilitate access to agricultural credit, invest in rural infrastructure, and promote farmer education programs to improve purchasing power and awareness. Ultimately, adapting marketing strategies to align with local economic and cultural conditions can drive greater adoption of hybrid seeds, boost agricultural productivity, and contribute to the long-term sustainability of rural farming communities.

1. Introduction

The development of the maize seed industry depends on an effective marketing mix—product, price, promotion, and place—to meet farmer needs and maintain a competitive advantage [1]. Firms must continuously develop strategies to enhance customer satisfaction and strengthen market position [2,3]. High-quality seed varieties tailored to local conditions, competitive pricing, targeted promotions, and efficient distribution networks are essential for adoption and accessibility [4]. A well-implemented marketing mix not only drives demand and innovation but also supports the development of a resilient supply chain, boosting farmer confidence in reliable, high-quality seeds [5,6].

Maize plays a central role in the development of Indonesia’s agricultural sector, being the second most important food crop after rice and accounting for 19–20% of the total food crop area [7]. Its importance extends beyond direct consumption, as it is also a vital component in livestock feed and the food industry, supporting broader economic development [8]. To meet the growing demand and achieve self-sufficiency, the government has prioritized policies that support the development of maize production, including expanding planting areas, increasing cropping intensity, and promoting mechanization [9]. Additionally, breeding programs have contributed to the development of maize varieties with enhanced traits such as shade tolerance, drought resistance, and disease resistance, helping farmers overcome production challenges [8]. However, despite these developments, the sector continues to face persistent challenges, including limited land availability, inadequate infrastructure, and climate-related risks, which hinder further development [9]. Addressing these barriers requires targeted strategies to enhance competitiveness, promote sustainability, and support the development of decentralized agricultural systems. Improved government services and better distribution networks are also critical for sustaining the long-term development of the maize industry in Indonesia [9].

The maize cultivation in Soppeng District experienced significant growth from 2018 to 2022. Both the harvested area and production saw steady increases over the years, with production reaching its highest point in 2021. Although there was a slight decline in both harvested area and production in 2022, the overall trend remained positive. Productivity also improved over the period, reflecting advancements in farming practices. Despite a minor drop in the final year, the data highlight continuous progress in maize farming in the region during this five-year span.

Table 1 shows the maize cultivation in Soppeng District’s notable growth, from 2018 to 2022. The harvested area expanded at an average rate of 20.14% per year, peaking at 39,176.30 hectares in 2021. Production increased by 24.09% annually, reaching 195,504 tons in 2021, before slightly declining in 2022. Productivity also improved from 4.51 tons per hectare in 2018 to 4.99 tons per hectare in 2021, though it dipped to 4.86 tons per hectare in 2022, with an overall growth rate of 2.52%. These figures reflect positive developments in maize farming during the period.

Table 1.

Development of harvested area, production and productivity of maize crops in Soppeng District, 2018–2022.

The steady growth in maize planting area, production, and productivity in Soppeng District, as shown in Table 1, highlights the increasing demand for maize seeds, particularly hybrid varieties, presenting a lucrative opportunity for companies like PT Bisi International Tbk’s BISI brand. However, the highly competitive nature of the hybrid seed market necessitates continuous product evaluation to maintain market prominence. Since farmers, the primary consumers of hybrid seeds, base their purchasing decisions on detailed product information that aligns with their specific needs and preferences, it becomes critical to investigate effective marketing strategies for BISI hybrid seeds [6,10]. This study aims to identify marketing approaches that successfully communicate product benefits, cater to farmer preferences, and differentiate BISI seeds in a crowded market [11]. These insights will help shape farmers’ decisions to choose BISI products over competitors.

To conduct the study for analyzing the influence of the marketing mix (product, price, promotion, and distribution) and personal factors on farmers’ purchasing decisions for BISI hybrid maize seeds, a conceptual framework is necessary. The framework integrates both marketing and behavioral components to understand how these elements interact. Based on the literature, the marketing mix serves as a stimulus that influences consumer behavior, including farmers’ decisions to adopt specific hybrid maize seeds [12]. Each element of the marketing mix—product attributes, pricing strategies, promotional efforts, and distribution channels—directly affects the perception and decision-making process of consumers [13,14,15].

Additionally, personal factors such as cultural, social, and psychological elements play a significant role in shaping farmers’ preferences and behaviors [16,17]. These factors influence how farmers perceive and respond to marketing stimuli. For instance, the cultural norms of farming communities, individual knowledge about hybrid seeds, and social influences from farming networks can impact seed selection decisions. The interaction between the marketing mix and these personal factors creates a comprehensive understanding of the consumer [18,19].

The conceptual framework will therefore model the relationship between the marketing mix and personal factors and analyze how this relationship influences purchasing decisions for BISI maize seeds. The goal is to identify how product, price, promotion, and distribution strategies can be tailored to align with farmers’ personal motivations and preferences, leading to improved marketing strategies and higher adoption rates of hybrid maize seeds [20,21,22]. This understanding is crucial for enhancing customer satisfaction and fostering long-term loyalty, which, in turn, supports business growth and sustainability [13].

The literature on factors influencing farmers’ preferences in purchasing hybrid maize seeds highlights the role of both individual and environmental factors in decision making. The key variables that impact farmers’ choices include adherence to tradition, family considerations, and perceptions of hybrid seed adequacy and trends [20,21,22,23,24]. These variables align with the broader concept of the marketing mix, which includes product, price, promotion, and distribution. Another factor, such as land tenure and information sources, is not directly examined in the marketing mix [25,26,27]. Meanwhile, the study establishes a connection between the marketing mix and sales volume, demonstrating that product marketing, along with the interaction of the 4Ps (product, price, promotion, and distribution), can significantly influence purchasing decisions [12,28,29]. However, many studies lack a comprehensive understanding of how these elements interact with cultural, social, and psychological factors within specific regional markets [30,31,32,33]. This gap underscores the need for research into how marketing mix elements affect consumer behavior in the agricultural context of BISI maize seeds, allowing for more effective strategies tailored to local preferences and market dynamics. While previous studies have examined various factors influencing farmers’ purchasing decisions for hybrid maize seeds, much of the existing literature has either focused on broad generalizations or urban contexts, neglecting the specific dynamics of rural or regional markets.

Additionally, there is limited understanding of how the marketing mix interacts with personal factors like cultural, social, and psychological aspects, particularly within the agricultural setting of BISI hybrid maize seeds in regional areas like Soppeng District. Thus, a gap exists in understanding how the marketing mix can be tailored to address the specific needs and preferences of local farmers, thereby enhancing their purchasing decisions in the context of hybrid maize seed products.

This study aims to analyze the influence of the marketing mix—product, price, promotion, and distribution—on farmers’ purchasing decisions for BISI hybrid maize seeds. Additionally, it examines how personal factors, including cultural, social, and psychological elements, shape farmers’ preferences when selecting these seeds. This study investigates the interaction between the marketing mix and personal factors to understand their combined effect on purchasing behavior in rural regions. Moreover, it aims to formulate strategies to develop maize hybrid seed marketing, ensuring greater accessibility and adoption among farmers. Finally, this study seeks to identify the most effective marketing strategies to enhance consumer engagement and improve market performance by addressing marketing mix elements and the personal factors influencing farmers’ decision making.

By examining the interaction between marketing elements and personal factors like cultural, social, and psychological influences, this research provides valuable insights into local farmers’ preferences and behaviors. These insights are essential for seed producers and agricultural marketers to customize their strategies to better address the needs of farmers in Soppeng District, thereby improving product offerings and marketing effectiveness. For companies such as PT Bisi International Tbk, this study offers data-driven recommendations to enhance customer satisfaction, market penetration, and sales performance in regional markets. Furthermore, by encouraging the adoption of hybrid maize seeds, this study has broader implications for boosting agricultural productivity, food security, and sustainability in Soppeng District, serving as a valuable model for future research in similar rural settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Time Research

This study selected Soppeng District, South Sulawesi Province, as the research site. The district is strategically located, bordered by Bone District to the south, Wajo District to the east, Sidenreng Rappang District to the north, and Barru District to the west. Soppeng was purposely selected as the research location due to its dominant market share in Bisi brand hybrid maize seeds, making it an ideal setting for analyzing the factors influencing purchasing decisions.

Soppeng District, a central maize-producing area in South Sulawesi, was selected as the study site due to its significant role in agricultural production. With a vast dryland farming area and many maize farmers, Soppeng is ideal for analyzing seed adoption and purchasing decisions. BISI hybrid seeds, particularly BISI-2 and BISI-18, dominate the market due to their high-yield potential and strong distribution networks. Their widespread availability makes them the preferred choice among farmers. Given these factors, this study employed a random sampling approach to ensure a representative selection of maize-farming households. It allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the region’s market dynamics and seed preferences.

Farmers in South Sulawesi play a central role in maize cultivation, benefiting from access to a diverse range of labeled seed types, including hybrid and composite varieties. Among the most widely used hybrid seeds are BISI-2, BISI-18, and NK 007, along with locally developed varieties like NA1 and NA2. BISI-2 is favored for its resistance to lodging and large seed size, while BISI-18, with its impressive yield potential of up to 12 tons per hectare, offers a promising future for maize cultivation. The widespread adoption of BISI hybrid seeds is primarily attributed to well-established distribution networks, particularly in key maize-producing regions such as Soppeng. This accessibility enables farmers to secure high-quality seeds, enhancing productivity and crop reliability. Notably, Soppeng District holds the largest market share for BISI hybrid maize seeds, accounting for 138,009 kg—or 40.39%—of the total 341,713 kg sold in South Sulawesi in 2023.

2.2. Data Source and Data Collection

This study utilizes both primary and secondary data sources for a comprehensive investigation. Primary data were collected through direct interviews with respondents using well-structured questions and pre-prepared questionnaires, ensuring a systematic and efficient data collection process. These interviews provided valuable firsthand insights into the research variables, capturing perspectives from those directly involved. This study obtained secondary data from relevant institutions, including the statistical and district agricultural offices, and gathered additional insights through interviews with agricultural extension workers and seed distributors. By integrating primary and secondary data, this research ensures a thorough and rigorous analysis, offering key insights into the dynamics of the selected topic.

This study employed a purposive sampling approach to ensure that respondents were specifically selected from farmers who actively understand and use BISI hybrid maize seeds. This study targeted customers of ten retailers specializing in hybrid maize seeds in Soppeng District. The selection process was thorough, involving the identification of farmers who had recently purchased BISI seeds through retailer records and farmer self-reporting. A total of 100 respondents were selected from these retailers to ensure that only those with direct experience using BISI hybrid maize were included. This approach allowed the study to gather reliable insights from experienced users, focusing on their adoption patterns, decision-making processes, and perceptions of seed performance. While this method strengthens the validity of responses, it inherently limits broader generalization to all maize farmers in the region, as the sample consists exclusively of BISI hybrid maize users rather than a representative cross-section of all maize growers.

The data collection team performed comprehensive interviews using a standardized questionnaire to gather primary data. This questionnaire addressed numerous critical domains, encompassing the socioeconomic profile of farmers, elements of the marketing mix (pricing, product, place or distribution, and promotion), and facets of personal and decision-making behavior. In-person interviews with participants directly collected data, facilitating a thorough examination of each questionnaire item. Researchers administered the questionnaire in real time, utilizing the information provided by each participant to gather details pertinent to the study’s objectives.

Each interview session lasted between 75 and 100 min and involved a total of 33 questions. Of these, 20 questions focused on the marketing mix, examining how price, product, place, and promotion factors influenced farmers’ decisions. Additionally, 13 questions explored various factors shaping farmers’ behavior when purchasing maize seeds, and six questions collected data on the socioeconomic identities of the respondents. It measured the marketing mix and consumer behavior responses using a Likert scale, ranging from “very” [5] to “very not” [1], with ellipses representing specific conditions relevant to each question element. This scale provided a nuanced way to assess respondents’ attitudes, allowing researchers to interpret qualitative responses quantitatively.

2.3. Data Analysis

This study’s data analysis will focus on examining causal relationships between variables to identify significant connections and develop an empirical model that illustrates the interactions between these variables and their supporting factors. We will use the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis tool to achieve this. SEM is particularly effective for exploring complex relationships between multiple variables simultaneously, making it ideal for this study’s objectives. Software such as Excel and PLS 4.0 (linear structural relationship) will support the analysis, ensuring precise calculations and model accuracy. This study will apply the goodness-of-fit test (GFT) to evaluate the model’s appropriateness. Three important signs show that a structural model fits well: a p-value of at least 0.05, an RMSEA of at least 0.08, and a comparative fit index (CFI) of at least 0.90.

SEM (Structural Equation Modeling) is a versatile statistical technique that combines several types of analyses, allowing researchers to test complex relationships and measure the dimensions of concepts. This approach enables the researcher to explore both regressive and dimensional questions, providing a detailed understanding of how different factors influence each other [19]). SEM is very useful because it uses instruments that measure constructs accurately and consistently, making sure that the results are valid (reflecting the intended constructs) and reliable (consistently accurate over time). To ensure this, it is essential to conduct validity and reliability tests on the research questionnaire before proceeding with the analysis.

To develop a comprehensive SEM model, one must undertake several steps, such as defining the theoretical framework, collecting and preparing data, validating the measurement model, and evaluating the structural model using the specified goodness-of-fit criteria. These steps are critical to ensure that the final model is robust, reliable, and provides valuable insights into the relationships between the variables under study.

- (a)

- Theoretical Model Development

The first step in developing a SEM model is to establish a theoretical foundation that is well supported by existing research. This requires the researcher to conduct a thorough review of relevant literature and previous studies to ensure that the proposed model is both theoretically sound and justified. The process involves identifying key variables and relationships that have demonstrated influence on the study area, thereby grounding the model in a robust theoretical framework. This study will develop the SEM model to identify and formulate the factors influencing the development of corn farming in South Sulawesi. By drawing on insights from prior research and aligning them with the specific conditions of corn farming in the region, the model will provide a comprehensive understanding of the key drivers behind successful corn farming practices and offer guidance for further development efforts.

- (b)

- Path Diagram Development

Path diagrams, according to researchers, are a valuable tool because they simplify the visualization of relationships within the tested model. These diagrams represent constructs and their interconnections through arrows, where straight arrows indicate a direct causal relationship between constructs, and curved lines with arrows at both ends depict correlations between them. The model distinguishes between two types of constructs: exogenous and endogenous [34]. Arrows pointing away from exogenous constructs, or independent variables, indicate that other variables within the model do not predict them. Conversely, one or more constructs influence endogenous constructs, which can also predict other endogenous variables, thereby establishing causal relationships. In this study, the analysis will follow a series of steps using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). In the first step, we determine the resampling method, specifically bootstrapping, which uses the entire original sample to generate multiple resamples for a more robust analysis of structural equations. After conceptualizing the model and selecting the algorithm and resampling methods, we draw a path diagram. The analysis converts the path diagram into an equation system for easier interpretation and understanding, visually representing the inner and outer models.

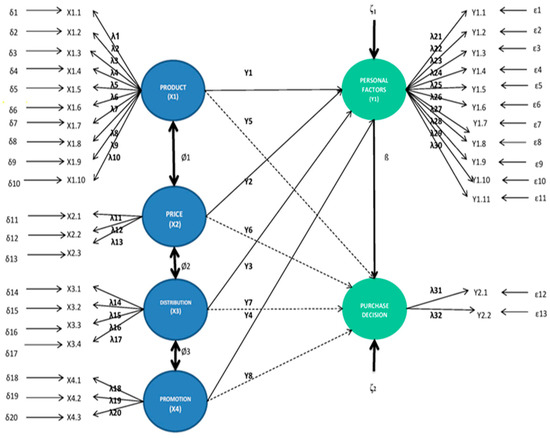

Using this structured approach, the analysis will examine the variables in this study to identify causal relationships and provide insights into the influence of the marketing mix on personal factors and purchasing decisions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Outer model of marketing mix strategies and personal factors influencing hybrid maize seed purchases.

In the structural equation model (SEM), the direction of arrows indicates the causal relationships between latent variables. The arrows demonstrate both direct and indirect effects of marketing mix strategies (products, price, distribution, promotion) and personal factors on farmers’ purchase decisions regarding hybrid maize seeds. The relationships can be systematically explained as follows:

- Direct Effects of Marketing Mix Strategies on Purchase Decision (→)

Product → Purchase Decision: The quality of the product, including brand, packaging, productivity, and yield, directly influences farmers’ buying decisions.

Price → Purchase Decision: Pricing strategies, such as price levels, discounts, and price variation, directly impact purchase decisions by affecting perceived value and affordability.

Distribution → Purchase Decision: Availability of products, convenient sales locations, and access to multiple retailers have a direct positive impact on farmers’ purchasing choices.

Promotion → Purchase Decision: Advertising, door prizes, and sales promotions directly influence purchase intentions by creating awareness and generating interest.

- Indirect Effects of Marketing Mix Strategies on Personal Factors (→)

Product → Personal Factors: High-quality products (e.g., good brand and high yield) influence farmers’ trust, perceptions, and preferences.

Price → Personal Factors: Attractive pricing strategies affect economic considerations and lifestyle choices.

Distribution → Personal Factors: Convenient and widespread product availability enhances farmers’ perceptions of accessibility and satisfaction.

Promotion → Personal Factors: Effective promotional strategies increase farmer interest and positive attitudes toward the product.

- Indirect Effects of Personal Factors on Purchase Decision (→)

Personal Factors → Purchase Decision: Personal characteristics, such as interest, trust, lifestyle, economic condition, and social influences, directly affect purchasing choices. Farmers with strong positive attitudes and economic readiness are more likely to buy hybrid maize seeds.

The model’s arrow directions show how marketing mix methods directly affect purchasing decisions and indirectly influence personal aspects that determine buying behaviour. This structure shows how complicated and interdependent external marketing and farmer attributes are in hybrid maize seed purchasing decisions.

After developing and illustrating the theoretical framework and model in a flowchart, the next crucial step is to transform the model specification into a series of equations. This process involves translating the visual representation of constructs and their relationships, as depicted in the path diagram, into mathematical terms that define the interactions between variables. The theoretical model [34] has previously identified the causal relationships and correlations between exogenous and endogenous variables, which each equation represents. By converting the model into equations, researchers can systematically test the hypothesized relationships using statistical software, such as PLS-SEM or other similar tools. These equations make it possible to precisely measure how strong and important the connections are between constructs. This helps us learn more about how the independent (exogenous) and dependent (endogenous) variables affect each other. This step is essential for empirical testing and validation of the theoretical model, ensuring that the relationships outlined in the flowchart are both statistically supported and aligned with the underlying theory.

The series of equations can be seen as follows:

Measurement Model Equation:

X1 = λ1jX1j + δJ j = (1, 2, 3, …, 10)

X2 = λ2jX2j + δJ j = (11, 12, 13)

X3 = λ3jX3j + δJ j = (14, 15, …, 17)

X4 = λ4jX4j + δJ j = (18, 19, 20)

Y1 = λ1Jx1j+ εL j = (21, 22, 23, …, 30)

L = (1, 2, 3, …, 11)

L = (1, 2, 3, …, 11)

Y2 = λ2Jx2j + εL j = (31, 32)

L = (12, 13)

L = (12, 13)

Structural equation model:

- Marketing mix model

XiJ = λjXj + δj

- 2.

- Personal factor model

Y = γkXj+ ζ1 j = 21, 22,…, 30

k = 1, 2, 3, 4

k = 1, 2, 3, 4

- 3.

- Purchasing decision model

Y2 = β Y1 + ζ2

Notes:

- Y: Vector of endogenous latent variables;

- X: Matrix of exogenous latent variables;

- λ: Direct relationship of exogenous or endogenous variables to their indicators;

- β: Vector of path coefficients between endogenous variables;

- δ: Measurement error of the exogenous variable indicator;

- ε: Measurement error of the endogenous variable indicator;

- ζ: Measurement error (error) in the structural equation;

- γ: Path coefficient vector of exogenous to endogenous variables.

Specification of the relationship between latent variables and their indicators (outer model).

Table 2 presents the research model testing design, outlining the hypotheses and corresponding statistical tests used to evaluate the relationships between key variables. The model examines the overall fit of the data using goodness-of-fit indicators, including p-values, RMSEA, and CFI, to determine whether the sample covariance matrix aligns with the estimated population covariance matrix. Additionally, the model explores the influence of personal factors—product, price, distribution, and promotion—on purchase decisions. The study tests the hypotheses using t-values and determines statistical significance at a threshold of 1.96. This analysis will provide insights into how the marketing mix components shape consumer behaviour and purchase decisions.

Table 2.

Research model testing design.

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

Table 3 depicts the characteristics of maize farmer respondents, which provide valuable insights into how the marketing mix (product, price, place, promotion) and personal factors influence their purchasing decisions for Bisi corn seeds. Farmers’ farming experience (ranging from 2 to 59 years) and land size (from 0.2 to 2 hectares) suggest that more experienced or larger-scale farmers might prioritize higher-quality seeds, while newer or smaller-scale farmers may focus on affordability. The variation in income (IDR 2,500,000 to IDR 10,000,000 per month) indicates different levels of price sensitivity, with wealthier farmers possibly opting for premium-priced seeds and lower-income farmers seeking cost-effective options.

Table 3.

Characteristics of maize farmer respondents.

In terms of promotion, the education levels of farmers (4 to 16 years) suggest the need for targeted marketing strategies. More educated farmers may respond to detailed information about seed performance, while less educated farmers might benefit from simpler promotional messages, such as demonstration plots or peer recommendations. Age, family size, and farming experience are additional personal factors that influence purchasing decisions. Older, more experienced farmers might rely on trusted seed brands, while younger or less experienced farmers may be more open to new products and trends, highlighting the importance of understanding these personal factors when developing marketing strategies for Bisi corn seeds.

3.2. Analysis of Marketing Mix Factor

The findings emphasize the need for agricultural marketing strategies to prioritize product quality and pricing, as these are the most influential factors in farmers’ purchasing decisions. Distribution channels also play a critical role, particularly in rural areas, where accessibility can make or break purchasing behavior. While promotional activities may raise awareness, they are less effective unless they align closely with farmers’ personal and cultural contexts. Addressing the negative influence of personal factors, such as risk aversion and trust, could improve adoption rates and overall purchasing behavior.

Table 4 presents the SEM parameters, demonstrating robust reliability and validity across all constructs: product, price, distribution, promotion, personal factors, and purchase decision. Key indicators such as outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) highlight the strength of these constructs. Notably, product and price emerge as the most influential factors driving farmers’ purchasing decisions, given their high outer loadings and strong reliability scores. Personal factors and distribution also play significant roles, particularly in terms of accessibility and farmers’ preferences. Promotion, on the other hand, appears to have a weaker impact on purchase behavior, making it less influential in comparison. Overall, the findings align with the SEM analysis, reinforcing the critical role of product quality and pricing in shaping buying decisions in agricultural markets.

Table 4.

Evaluation of measurement model.

3.2.1. Product (X1)

The Product (X1) construct, measured by 10 items including brand, packaging variations, pest and disease tolerance, productivity, and yield, shows strong outer loadings ranging from 0.802 to 0.920, demonstrating significant contributions of each item to the overall construct. The construction explains more than 71.9% of the variance, as shown by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.956, a composite reliability (CR) of 0.958, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.719. This means that it is fully reliable and valid. The SEM results support these findings, identifying product features as key drivers of farmers’ purchasing decisions. The studies emphasize the importance of yield, pest resistance, and resilience to environmental stresses in influencing farmers’ choices and adoption behaviors [35,36]. High loadings for input (0.920) and yield (0.864) further underscore the role of quality and productivity in purchasing behavior. However, while product attributes like quality and yield play a critical role, other factors, such as access to information and social networks, may also influence farmers’ adoption of new technologies [37]. Socioeconomic conditions, including farm size and credit availability, significantly influence adoption rates [38]. Thus, while product characteristics are essential, broader contextual factors should also be considered to fully understand farmers’ purchasing decisions in agricultural markets. This holistic view can provide more comprehensive insights into how businesses might better support farmers in adopting new technologies and making purchasing decisions.

3.2.2. Price (X2)

This study confirms that Price (X2) is a significant and reliable construct in influencing farmers’ purchasing decisions, as evidenced by strong outer loadings ranging from 0.854 to 0.928, with price variation being the most influential. Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.855, the composite reliability (CR) value of 0.856, and the AVE value of 0.777 demonstrate the construct’s strong and reliable nature. These values explain a large part of the variation in the measurement items. In agricultural markets, where financial constraints are prevalent, prices are a critical factor in decision making. The price variation had the highest outer loading (0.928), underscoring its importance in purchasing decisions. The price fluctuations, particularly price variation and discounts, significantly impact farmers’ choices, with price variation providing the flexibility farmers need to adjust to market and income volatility [39].

However, additional research suggests that while price is a key factor, other elements such as access to credit and information also play a significant role in agricultural purchasing behavior [37]. Similarly, studies indicate that socioeconomic factors, such as farm size and access to markets, further shape purchasing decisions [38]. These broader contextual factors complement the price construction by providing a more comprehensive understanding of farmers’ decision-making processes. Policymakers and businesses can leverage these insights to develop holistic pricing strategies that not only cater to financial constraints but also address broader socioeconomic realities, ultimately supporting more sustainable purchasing behavior in agricultural markets.

3.2.3. Distribution (X3)

This study confirms that distribution (X3) is a significant and reliable construction in the model, measured by factors such as product availability, sales location, number of retailers, and convenience of the place. The outer loads range from 0.814 to 0.932, with “convenience of place” showing the highest loading, emphasizing its critical importance in farmers’ decision-making processes. With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.886, a composite reliability (CR) of 0.889, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.747, the construct is highly reliable. It has strong internal consistency, and a lot of the variance is explained. Distribution plays a vital role in ensuring farmers’ access to inputs, especially in rural areas where infrastructure and logistical issues can pose barriers. In agricultural markets, poor infrastructure often limits product availability, impacting farmers’ ability to make timely purchases [40,41]. Similarly, the importance of reliable distribution networks in improving market access for smallholders further supports this study’s emphasis on distribution’s role in shaping purchasing behavior [42,43].

However, while distribution is crucial, the effectiveness of distribution systems also depends on farmers’ access to information, which can influence their ability to navigate the market and find available inputs [37,44]. Additionally, the socioeconomic factors, such as the purchasing power of farmers and the availability of financial resources, are critical in determining whether distribution systems can be effectively utilized [38,45]. These references suggest that while distribution plays a key role, broader factors such as market information and socioeconomic conditions should also be considered for a comprehensive understanding of purchasing behavior in agricultural contexts.

3.2.4. Promotion (X4)

This study reveals that while promotion (X4) is a reliable construction, it is not a critical factor in influencing purchasing decisions. Measured through advertising, door price, and sales promotions, its outer loadings range from 0.832 to 0.862, indicating moderately strong correlations. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.802, composite reliability (CR) of 0.813, and average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.715 confirm the construct’s reliability and explain over 71.5% of the variance. However, SEM shows that promotion has a weaker influence on purchase decisions compared to factors like product quality and price. This suggests that tailoring promotional efforts to the unique cultural and economic contexts of rural farmers, who prioritize product reliability and affordability, can improve effectiveness [46]. In developing markets where access to information is limited, promotions may not reach or sway farmers as strongly as other factors such as pricing and product features [47]. While promotions can generate short-term awareness, intrinsic factors such as product value and reliability often drive long-term purchasing decisions [48]. Thus, although promotion raises initial awareness, its influence on sustained purchasing behavior in agricultural markets remains minimal.

3.2.5. Personal Factors (Y1)

This study demonstrates that personal factors (Y1) are a highly reliable and valid construct, measured through 11 key items, including farmer interest, needs, age, lifestyle, perception, trust, group preference, family, education, social influences, and economic conditions. The outer loadings, ranging from 0.804 to 0.911, indicate strong correlations between these factors and their respective indicators. With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.960, a composite reliability (CR) of 0.960, and an average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.713, the construct is even more reliable. This suggests that personal factors account for a large part of the variation in the items. However, SEM reveals that personal factors negatively influence purchasing decisions, possibly due to farmers’ risk aversion, trust issues, and perception, which may deter them from making purchases in uncertain markets. This underscores the critical role of trust and social influences in rural markets, where farmers often rely on community recommendations and the credibility of products [49,50].

Information asymmetry in rural areas can exacerbate the influence of personal factors, making farmers hesitant to make purchasing decisions without reliable sources of information [47,51]. Social and group dynamics play a crucial role in shaping decision making, as personal factors like group preferences often hinder purchasing when they align with community norms of caution and risk avoidance [38,52,53]. These dynamics suggest that while trust and social influences are critical in shaping farmers’ attitudes, addressing them through targeted interventions and trust-building strategies is essential for encouraging more proactive purchasing behavior in agricultural markets. By fostering a reliable information flow and enhancing trust within rural communities, interventions can mitigate the negative impact of risk aversion and promote more confident, informed purchasing decisions.

3.2.6. Purchase Decision (Y2)

The study results validate that the purchase decision (Y2) construct exhibits excellent reliability and validity, as evidenced by both purchasing and repurchasing behaviors. The outer loadings of 0.939 and 0.940 indicate a strong correlation between the construction and its measurement items. The construct exhibits robust reliability, evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.867, a CR of 0.867, and an AVE of 0.883. This means that it accounts for a significant portion of the variability in its indicators. The results highlight the importance of purchasing and repurchasing behaviors as essential outcomes, establishing the construct as a vital dependent variable in the SEM study. In agricultural markets, product satisfaction and the overall purchasing experience are fundamental determinants of both first and repeat buying decisions, especially where dependability and cost-efficiency are paramount [48].

Reliable product performance and accessible information significantly influence farmers’ decisions to repurchase, with farmers more inclined to do so when they are confident in a product’s efficacy [47,54]. Positive experiences with agricultural inputs foster long-term loyalty, supporting the study’s finding of a high outer loading for repurchase behavior. The products strongly influence initial purchasing decisions, but consistent performance and transparency in information are key to increasing repurchase rates [38,55]. This highlights the critical role that purchasing decisions play in shaping farmers’ long-term buying habits, reinforcing the importance of trust and product reliability in agricultural markets.

3.3. The Influence of Marketing Mix Elements on Purchase Decisions

This study provides essential insights for developing decision-making strategies, particularly regarding product and pricing, which significantly and positively affect purchasing decisions. While advertising does not directly influence purchasing behavior, it indirectly impacts personal factors, revealing the complexity of how marketing activities shape customer decisions. Personal factors show a negative correlation with purchasing, suggesting that certain personality traits may hinder specific buying situations. In contrast, distribution affects purchasing decisions without influencing personal traits. The SEM analysis uncovers key relationships that emphasize the importance of product, price, promotion, personal factors, and distribution in shaping farmers’ decision making, offering a framework to optimize marketing strategies in agricultural markets.

Table 5 illustrates key relationships in farmers’ decision making, showing that distribution significantly impacts purchasing decisions (path coefficient = 0.500, p = 0.048) but does not affect personal factors. Price has a positive and significant influence on both purchase decisions (path coefficient = 0.708, p = 0.011) and personal factors (path coefficient = 0.285, p < 0.000). The product has the strongest impact on both purchasing decisions (path coefficient = 1.638, p = 0.0003) and personal factors (path coefficient = 0.872, p < 0.000). Promotion does not directly influence purchasing decisions (path coefficient = 0.181, p = 0.516), but it negatively affects personal factors (path coefficient = −0.140, p = 0.001). Lastly, personal factors negatively influence purchasing decisions (path coefficient = −2.102, p = 0.0004), suggesting that certain traits may hinder purchasing behavior. These findings highlight the complex interplay between distribution, price, product, promotion, and personal factors in shaping farmers’ purchase decisions.

Table 5.

Factors influencing purchase decisions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Product and Purchase Decision

The relationship between product attributes and purchase decisions shows that product characteristics have the strongest positive influence on farmers’ purchasing behavior. This emphasizes the importance of product quality, reliability, and suitability to farmers’ needs in their buying decisions. Research consistently indicates that farmers prioritize products that boost productivity and profitability, especially in agricultural contexts. Several studies highlight how durability and functionality drive purchase decisions, with farmers in developing countries seeking products that withstand environmental challenges and improve yields [56,57]. When products align with farmers’ needs and offer practical benefits, adoption rates and purchase decisions increase significantly [58,59].

4.2. Price and Purchase Decision

The relationship between price and purchase decisions indicates that price is a highly significant and positive factor influencing farmers’ purchasing behavior, though less so than product attributes. When making decisions, farmers consider both the affordability and value for the money of inputs. In agricultural economics, price plays a key role in how farmers balance input costs with expected returns. The study links farmers’ price sensitivity to their income levels and profitability goals, ensuring that input prices align with production objectives [60]. Additionally, smallholder farmers are particularly sensitive to price due to fluctuating market conditions and uncertain income, though they prioritize product quality over price when making purchases [61,62].

One of the most significant findings from the analysis is the positive and substantial influence of product quality and price on farmers’ purchase decisions. Product attributes such as yield potential, resistance to environmental stress, and cost-effectiveness play a critical role in shaping these decisions, particularly in rural and resource-constrained settings [36,59]. Farmers prioritize products that offer value and long-term benefits, making their choices based on both perceived and actual returns on investment [63]. They seek sustainable agricultural practices that enhance productivity and profitability while also ensuring environmental health [64]. These considerations not only meet farmers’ immediate economic needs, but also contribute to their farming operations’ long-term viability, ensuring their sustainability for future generations. This highlights the importance of providing products that balance economic efficiency with sustainability to meet the complex needs of modern agriculture.

4.3. Price and Personal Factors

The positive and significant relationship between price and personal factors underscores the influence of financial stability, economic expectations, and financial literacy on how farmers perceive and respond to price variations. Research suggests that farmers with higher levels of financial literacy or greater disposable income are better equipped to understand and adapt to price fluctuations, making them more inclined to invest in higher-priced products that add long-term value [65,66]. Additionally, farmers with stable financial conditions, including consistent income, access to credit, and a higher tolerance for risk, are more likely to view these higher-priced products as beneficial investments for future productivity, especially when they also have access to financial services and information [67]. This reinforces the idea that financial literacy and resource access are critical factors influencing farmers’ pricing strategies and investment decisions, as supported by earlier studies [68,69].

4.4. Promotion and Personal Factors

The negative and significant relationship between promotion and personal factors suggests that current promotional strategies often fail to resonate with farmers’ unique characteristics and preferences, leading to skepticism or resistance. Promotional efforts frequently fall short when they do not consider the cultural, educational, or experiential backgrounds of their target audience [48]. In rural farming communities, where traditional practices dominate, promotional tactics that are poorly aligned or overly aggressive can foster distrust and disengagement [70]. Research demonstrates that farmers react negatively to campaigns that fail to cater to their specific needs, leading to a decrease in the adoption rates of agricultural inputs [71]. Likewise, marketing strategies that fail to adapt to local contexts often provoke resistance or passive rejection [72]. These findings highlight the critical need for promotional strategies that align with the values, traditions, and realities of farming communities to foster greater engagement and product adoption.

Researchers have found that promotion has a minimal direct impact on farmers’ purchase decisions, but it can negatively affect personal factors like trust and perception. Unless specifically tailored to the cultural and economic contexts of farmers, promotional activities in agricultural markets often lack effectiveness [73]. Poorly targeted promotions can even erode trust, reducing their potential influence on decision making [74]. Furthermore, unless promotions closely align with the needs and preferences of the target audience, they are unlikely to significantly influence purchasing behavior, even though they may temporarily increase awareness [48]. This highlights the importance of relevance and personalization in promotional efforts, particularly in markets where trust and long-term relationships are key drivers of purchasing behavior.

4.5. Distribution and Purchase Decision

The notable and substantial correlation between distribution and purchasing decisions highlights the essential function of distribution in shaping farmers’ buying behavior. Effective and dependable distribution routes are crucial for guaranteeing product availability and accessibility, especially in rural regions where prompt access to inputs is vital for agricultural operations [75,76]. In the agricultural and rural markets, where logistical difficulties are common, a strong distribution network is essential for surmounting obstacles to product accessibility [77,78]. This is especially crucial in areas with inadequate infrastructure, where efficient distribution can directly affect farmers’ access to essential inputs. Their research indicates that improving distribution networks significantly enhances access to agricultural products in remote regions, hence affecting farmers’ purchasing choices [79,80]. The findings align with the current study, emphasizing distribution as a crucial element in influencing purchase behavior and stressing the necessity for robust distribution strategies in agricultural markets.

Finally, this study found that distribution positively influences purchase decisions but does not significantly impact personal factors. This finding underscores the importance of distribution, particularly in terms of product availability and ease of access, in shaping farmers’ purchasing behavior. In agricultural markets, logistical challenges such as poor infrastructure and remote locations often hinder farmers’ access to critical inputs, making efficient distribution networks essential [81]. Similarly, timely access to agricultural inputs is a decisive factor in farmers’ purchase decisions, as convenience of access often outweighs personal preferences or perceptions [82]. When products are readily available at convenient locations, farmers are more likely to prioritize ease of access over individual factors such as brand loyalty or product quality [83]. Thus, improving distribution channels not only facilitates product availability but also plays a crucial role in farmers’ decision-making processes, independent of their personal characteristics or preferences.

4.6. Personal Factors and Purchase Decisions

Researchers have consistently found that personal factors significantly influence farmers’ purchasing behavior, often serving as barriers to adopting new technologies and inputs. Traits such as risk aversion, past experiences, and socioeconomic status can negatively impact decision-making processes, especially in agricultural settings. Key factors such as risk perception, education level, and familiarity with new technologies are critical in determining how farmers make purchasing decisions. For instance, studies have demonstrated that farmers with lower education levels or higher risk aversion are less likely to adopt innovative technologies or deviate from traditional methods [36,84]. Risk aversion inhibits farmers from investing in new inputs, even when these inputs offer significant potential for improving productivity [85]. This reluctance is further fueled by concerns about financial loss or a lack of trust in unfamiliar products.

These findings align with the work and more recent studies [86,87], highlighting that personal factors can substantially hinder purchasing decisions. This underscores the need for targeted interventions—such as educational programs and risk-sharing mechanisms—to address these barriers and build trust in new technologies. Without addressing these personal concerns, efforts to promote technological adoption may fall short, limiting farmers’ ability to benefit from agricultural inputs and practice advancements. Therefore, promoting awareness and creating supportive environments for farmers to make informed decisions are essential for enhancing the uptake of new technologies in agriculture [88,89].

4.7. Strategies to Develop Maize Hybrid Seed Marketing

A multi-faceted approach is essential to overcoming hybrid maize seed marketing challenges. It includes improving rural infrastructure, enhancing promotional efforts through farmer education and demonstration plots, and expanding financial support such as subsidies and flexible payment options. Strengthening trust through seed performance guarantees and fostering better stakeholder coordination will improve seed accessibility and adoption. By addressing these key areas, hybrid maize seed marketing can become more efficient, inclusive, and impactful, leading to greater farmer engagement and increased agricultural productivity in Soppeng District.

- (1)

- Strengthening Distribution Channels and Infrastructure: Enhancing the accessibility of hybrid maize seeds requires improving distribution networks and infrastructure. Establishing regional seed warehouses through public–private partnerships ensures continuous stock availability [90]. Strengthening agri-retail networks by supporting local input dealers and farmer cooperatives enhances seed availability in key farming areas [91]. However, agro-dealers remain unevenly distributed, primarily concentrated in high-potential agricultural zones [92]. Developing last-mile delivery systems like motorcycle and small-truck deliveries helps reach remote farmers more efficiently. Investing in rural road networks is essential to reducing transportation costs and improving accessibility for suppliers and farmers [93]. Additionally, seed companies require improved capacity in production, business operations, and marketing, while reducing dependence on imported varieties is crucial for farmers and agro-dealers. Upgrading the seed value chain demands technical and financial support alongside a conducive regulatory environment [93].

- (2)

- Reducing Costs and Improving Financial Accessibility: Several studies indicate that access to credit and financial resources significantly influences smallholder farmers’ adoption of hybrid seeds and fertilizers. Studies in Uganda, Kenya, and Malawi show that providing hybrid seeds during high liquidity increases adoption rates [94]. Access to credit and extension services positively affects the use of improved maize varieties and fertilizers [95,96]. However, credit constraints can limit adoption, as access to credit increases adoption among constrained households but does not affect those without constraints [96]. Other factors, including education levels, plot sizes, non-farm income, and proximity to input markets influence adoption rates [97]. Additionally, gender plays a role, with female farmers sometimes exhibiting higher adoption rates [94], while female-headed households often face challenges in fertilizer adoption [97].

- (3)

- Enhancing Farmer Awareness Through Improved Promotion Efforts: Research shows that a lack of awareness and ineffective promotion strategies hinder smallholder farmers in developing countries from adopting hybrid seeds. While demonstration plots and field days are commonly used to promote improved seeds, their effectiveness varies. One study found no significant impact on adoption rates after two seasons of demonstrations [98]. In contrast, another reported a 40% increase in adoption following farmer field days [99]. Adoption is influenced by socio-demographic characteristics, seed cost, yield potential, market access, and social networks [100]. Innovative strategies, such as offering hybrid seeds for purchase during high-liquidity periods, have effectively boosted adoption rates [94]. To enhance hybrid seed adoption, efforts should focus on raising awareness, providing targeted extension services, and addressing context-specific barriers. This underscores the need for tailored context-specific strategies. Additionally, considering gender differences in adoption patterns may lead to more effective promotion strategies [94,100].

- (4)

- Building Trust and Reducing Farmers’ Risk Aversion: Research shows that farmers’ reluctance to adopt hybrid seeds often arises from concerns about product quality and performance. Studies in Uganda indicate that up to 50% of hybrid maize seeds in local markets may be inauthentic, leading to negative returns for farmers [101]. Ensuring access to certified seeds during high-liquidity periods, such as after crop sales, can further enhance adoption [94]. However, brand loyalty plays a crucial role in seed selection, with farmers often favoring well-known, older hybrids over newer varieties [102]. Additionally, price promotions and product performance information have minimal influence on farmers’ choices when their preferred product is available [102].

- (5)

- Strengthening Market Linkages and Stakeholder Collaboration: Efficient seed marketing channels rely on collaboration among various stakeholders in the seed sector. Seed producer cooperatives (SPCs) are vital in enhancing seed availability and access for farmers in Ethiopia [103]). However, challenges such as limited essential seed availability, weak quality inspection, and poor market linkages hinder the development of the seed business [104]. Direct seed marketing programs have shown the potential to increase competition and improve seed distribution to farmers [105]. Addressing seed supply challenges requires strengthening formal and informal seed distribution channels, particularly for food-security crops [90]. Supporting SPCs through policy development, improving seed producers’ institutional and technical capacities, and establishing effective market information systems can contribute to a more efficient seed sector [103,104].

- (6)

- Improving Regulatory and Policy Support: Government policies are vital in promoting hybrid seed adoption and enhancing agricultural productivity. Studies in India, Pakistan, Uganda, and Malawi emphasize the significance of targeted interventions. Input subsidies can lower adoption costs and improve accessibility for smallholder farmers [106,107]. Ensuring seed quality through strict certification and anti-counterfeit measures is crucial, as poor-quality inputs lead to negative returns and discourage adoption [101]. Long-term government investment in irrigation infrastructure, market development, and extension services supports sustainable agricultural practices and mitigates production risks [106]. Education levels, farm size, market access, and social networks influence hybrid seed adoption [107]. Addressing these issues through comprehensive policies can boost hybrid maize adoption, increase yields, and improve farmers’ livelihoods [107].

5. Conclusions

Product quality and price emerge as the most influential factors in farmers’ purchasing decisions, with seed performance and affordability being their primary concerns. In rural areas, distribution plays a crucial role, as accessibility directly affects farmers’ ability to obtain high-quality seeds. Additionally, personal factors such as farming experience and income significantly shape purchasing behavior, highlighting the need for tailored marketing approaches. In contrast, promotional efforts have a relatively weaker impact, suggesting that conventional advertising strategies may not be as effective in influencing farmers’ choices. To enhance market penetration, seed companies should focus on developing high-performance seed varieties, optimizing pricing strategies, and strengthening distribution networks to improve access. From a policy perspective, facilitating agricultural credit schemes, investing in rural infrastructure, and promoting farmer education programs can enhance purchasing power and awareness. Moreover, targeted marketing strategies that align with local economic and cultural dynamics can further drive hybrid seed adoption, ultimately fostering agricultural productivity and sustainability in rural farming communities.

Limitation of the Study

While this study provides valuable insights into adopting and using BISI hybrid maize seeds, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, purposive sampling means that the findings are not fully generalizable to all maize farmers in Indonesia. This study focuses specifically on one seed variety (BISI hybrid maize), one manufacturer, and one region (Soppeng District), which limits its broader applicability. Farmers in different regions using alternative hybrid or local maize varieties may experience different adoption patterns and outcomes.

Second, selecting 100 respondents from ten retailers ensures that all participants have firsthand experience using BISI hybrid maize. However, it does not capture farmers purchasing seeds through informal channels or relying on non-hybrid maize varieties. Additionally, this study does not differentiate between small-scale and large-scale farmers or consider other factors that might influence seed adoption, such as access to credit, farm size, or extension services. Future research could expand the sample size and explore a more diverse group of farmers, including those who have considered but have not adopted BISI seeds, to understand adoption barriers and decision-making processes better.

Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable, user-specific insights into adopting and performing BISI hybrid maize, contributing to a better understanding of hybrid seed usage among experienced farmers in Soppeng District.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and R.D.; Methodology, S.R., R.D. and R.A.; Software, M.H.J., L.F. and H.N.B.A.; Validation, N.M.N.; Formal analysis, S.R., M.H.J., A.N.T., L.F., R.A. and H.N.B.A.; Investigation, M.H.J., A.N.T. and L.F.; Resources, M.H.J. and A.N.T.; Data curation, S.R. and L.F.; Writing—original draft, S.R. and H.N.B.A.; Writing—review & editing, R.D., R.A. and N.M.N.; Supervision, R.D. and N.M.N.; Funding acquisition, M.H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Permohonan Izin Penelitian (00555/UN4.20.1/PT.01.04/2024) on [17 January 2024].

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants. Verbal consent was obtained rather than written because of preventing respondent fatigue and maintaining participant engagement. We ensured that respondents were fully informed of the study’s objectives, methods, and how their information would be used. In addition, we adhered to local informal regulations and community norms to ensure that our study was conducted ethically. This included respecting local customs and schedules where we interviewed at times that did not interfere with daily prayers or other community obligations, and minimizing respondent burden by limiting the duration of interviews to a maximum of 60 min to prevent respondent fatigue and maintain participant engagement.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the findings of this article are available from the authors upon reasonable request. As the dataset captures unique local conditions with limited generalizability beyond its original context, access is carefully managed on a case-by-case basis. This approach ensures that the data are utilized responsibly and align with the study’s specific objectives. Researchers interested in accessing the data are encouraged to contact the authors to discuss their use and potential arrangements, ensuring that the data are applied appropriately and in ways that respect their context-specific nature.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend sincere gratitude to all individuals and groups who contributed valuable insights and information to this research, with special appreciation to the head and staff of the Agriculture Office of Soppeng District.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors listed immediately affirmed they have no affiliations or involvement with any organization or entity possessing financial interests related to the evaluated manuscripts. In addition, the authors declare that there are no non-financial competing interests, including political, personal, religious, ideological, academic, or intellectual considerations, that could influence the research. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results. The authors further confirm that there are no personal circumstances or interests that could be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of the reported research results.

References

- Singh, M. Marketing Mix of 4P’S for Competitive Advantage. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 3, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, D.W.; Mbowa, S. Strategic marketing problems in the Uganda maize seed industry. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2004, 7, 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jayasree, S.; Sivaramane, N.; Radhika, P.; Supriya, K. Marketing Strategies of Leading Cotton Seed Companies in Telangana State. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 38, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rutsaert, P.; Donovan, J. Exploring the marketing environment for maize seed in Kenya: How competition and consumer preferences shape seed sector development. J. Crop. Improv. 2020, 34, 486–504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hendarwan, D. Analysis of Market Driven Strategies To Increase Capabilities and Performances Advantages in Business. Int. Mark. Strategy Des. -Driven Co. Int. Conf. Financ. Manag. Econ. IPEDR 2023, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rachmawati, R. Peranan Bauran Pemasaran (Marketing Mix) terhadap Peningkatan Penjualan. J. Kompetensi Tek. 2011, 2, 143–150. [Google Scholar]

- Swastika, D.K.S.; Manikmas, O.A.; Sayaka, B. The Strategic Policy Options to Develop Maize and Feed Industry in Indonesia. Akp 2004, 2, 234–243. [Google Scholar]

- Syahruddin, K.; Azrai, M.; Nur, A.; Abid, M.; Wu, W.Z. A review of maize production and breeding in Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 484, 012040. [Google Scholar]

- Aldillah, R. National Maize Agribusiness Development Strategy. Anal. Kebijak. Pertan. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmawati, D. Metode Penelitian Manajemen. Ilmiah 2006, 14, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Nuryanti, S.; Swastika, D.K. Peran Kelompok Tani Dalam Penerapan Teknologi Pertanian. Forum Penelitiaan Agro Ekon. 2018, 29, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Irawan, P.R.; Purnamasari, P.; Darka DH, K.; Nawangsih, I.; Ayaty, N. Influence of Marketing-Mix on Purchase Decision at JNE. Int. J. Integr. Sci. 2023, 2, 791–802. [Google Scholar]

- Pahmi, P.; Tasrim, T.; Jayanti, A.; Rachmadana, S.L.; Irfan, A.; Alim, A. Marketing mix improves consumer purchase decisions. J. Ekon. Pembang. STIE Muhammadiyah Palopo 2023, 9, 368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, S.; Rukmana, D.; Rosmana, A. Effect of Marketing Mix on Consumer Decisions in Purchasing Pesticide Products Antracol 70 WP in Enrekang Regency (Case Study on Shallot Farmers Using Pesticides in Anggeraja District). Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2022, 7, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dewi, F.M.; Sulivyo, L.; Listiawati. Influence of Consumer Behavior and Marketing Mix on Product Purchasing Decisions. Aptisi Trans. Manag. (ATM) 2022, 6, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, N.R.; Johnson, E.J.; Croson, R.T.A. Let’s get personal: An international examination of the influence of communication, culture and social distance on other regarding preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 373–398. [Google Scholar]

- Kuliman, K.; Kemala, S.; Permata, D.; Almasdi, A.; Aina Fitri, N.H. Analysis of the Influence of the Marketing Mix on Consumer Purchasing Decisions Using the Structural Equation Modeling Method. Int. J. Islam. Econ. 2023, 5, 126–142. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, J.P.; Olson, J.C. Consumer Behavior & Marketing Strategy; Dana: South Jakarta, Indonesia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nurbaiti, S.; Syakir, F.; Susilowati, D. Analisis Faktor-Faktor yang Mempengaruhi Keputusan Petani Memilih Usahatani Jagung Manis Hibrida di Desa Bocek Kecamatan Karangploso Kabupaten Malang. J. Sos. Ekon. Pertan. Dan. Agribisnis 2020, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Abera, W.S.; Hussein, J.D.; Worku, M.; Laing, M.D. Preferences and constraints of maize farmers in the development and adoption of improved varieties in the mid-altitude, sub-humid agro-ecology of Western Ethiopia. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar]

- Permasih, J.; Widjaya, S.; Kalsum, U. Proses Pengambilan Keputusan dan Faktor-faktor yang Mempengaruhi Penggunaan Benih Jagung Hibrida Oleh Petani di Kecamatan Adiluwih Kabupaten Pringsewu. J. Ilmu Ilmu Agribisnis 2014, 2, 372–381. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Abbas, A.; Iqbal, M.A.; Rizwan, M.; Samie, A.; Faisal, M.; Sahito, J.G.M. What determines the uptake of multiple tools to mitigate agricultural risks among hybrid maize growers in Pakistan? Findings from field-level data. Agriculture 2021, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, K.B.; Blekking, J.P.; Attari, S.Z.; Evans, T.P. Maize seed choice and perceptions of climate variability among smallholder Farmersglob. Environ. Change 2017, 47, 51–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Vitale, J.; Park, P.; Adams, B.; Agesa, B.; Korir, M. Socioeconomic determinants of hybrid maize adoption in Kenya. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 617–631. [Google Scholar]

- Valkonen, A. Examining sources of land tenure (in)security. A focus on authority relations, state politics, social dynamics and belonging. Land. Use Policy 2021, 101, 105191. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Roux, L. A change based framework for theory building in land tenure information systems. Surv. Rev. 2012, 44, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, U.; Zevenbergen, J.; Todorovski, D. Exploring the Relation Between Transparency of Land Administration and Land Markets: Case Study of Turkey. In FIG Working Week 2020. Available online: https://research.utwente.nl/en/publications/exploring-the-relation-between-transparency-of-land-administratio/fingerprints/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Rahmawati, T.; Amaria, H. The Influence of Marketing Mix on Sales Volume At Rizqi Store, Tawangsari Village, Garum District, Blitar Regency. JOSAR J. Stud. Acad. Res. 2023, 8, 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama, A. Analysis of the Impact of Marketing Mix (4ps) on Sales Volume of Servvo’s Products in Jakarta. J. Soc. Res. 2022, 2, 456–475. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, R. Culture and its influence on elements of marketing mix. In Cultural Marketing and Metaverse for Consumer Engagement; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, P. The Critical & Cultural Marketing Mix. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.R.; Irena, A. The Impact of Marketing Mix, Consumer’s Characteristics, and Psychological Factors to Consumer’s Purchase Intention on Brand “W” in Surabaya. Ibuss Manag. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Baruno, A.; Ani Muliya Abady, J. The Influence of Marketing Mix Factors And Community Culture on The Behavior of Consumer Buying Interest in the Variety of Iced Coffee Milk at Janji Jiwa. Ekspektra J. Bisnis Dan. Manaj. 2022, 6, 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Al Mamun, A.; Naznen, F.; Masud, M.M. Adoption of conservative agricultural practices among rural Chinese farmers. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Just, R.E.; Zilberman, D. Adoption of agricultural innovations in developing countries: A survey. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 1985, 33, 255–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R. Analyzing technology adoption using microstudies: Limitations, challenges, and opportunities for improvement. Agric. Econ. 2006, 34, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Giller, K.E.; Witter, E.; Corbeels, M.; Tittonell, P. Conservation agriculture and smallholder farming in Africa: The heretics’ view. Field Crop. Res. 2009, 114, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Rathore, R. Farmer Buying Behaviour toward Major Agri-inputs-Finding from Fazilka District of Punjab. Econ. Aff. 2023, 68, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, J.L.; Ellis, S.D.; Agricultural Marketing and Access to Transport Services. Rural Transport Knowledge Base. Rural Transport Knowledge Base 2001. Available online: https://www.transport-links.org (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Årethun, T.; Bhatta, B.P. Contribution of Rural Roads to Access to- and Participation in Markets: Theory and Results from Northern Ethiopia. J. Transp. Technol. 2012, 02, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magingxa, L.L.; Alemu, Z.; van Schalkwyk, H. Factors influencing access to produce markets for smallholder irrigators in South Africa. Dev. S. Afr. 2009, 26, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakasone, E.; Torero, M.; Minten, B. The power of information: The ICT revolution in agricultural development. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, P.F.; Kozakiewicz, T.; Bachina, V.; Young, S.; Shisler, S. PROTOCOL: The effects of agricultural output market access interventions on agricultural, socio-economic and food and nutrition security outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2023, 19, e1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Prado, J.L.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, J.W.; Velez, J.I.; Garcia-Llinas, G.A. Reliability Assessment in Rural Distribution Systems with Microgrids: A Computational- Based Approach. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 43327–43340. [Google Scholar]

- Brinanti, B.; Wahab, Z.; Widiyanti, M.; Rosa, A. Influence of product quality promotion on the purchase decision of NPK retail non subsidy fertilizer at, P.T. Pupuk Sriwidjaja Palembang in the South Sumatra Region. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 4, 494–501. [Google Scholar]

- Aker, J.C. Dial “A” for agriculture: A review of information and communication technologies for agricultural extension in developing countries. Agric. Econ. 2011, 42, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2021; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S.; Christiaensen, L. Consumption risk, technology adoption and poverty traps: Evidence from Ethiopia. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 96, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.J. Contributions of social capital theory in predicting rural community inshopping behavior. J. Socio-Econ. 2001, 30, 475–493. [Google Scholar]

- Liebe, U.; Andorfer, V.A.; Gwartney, P.A.; Meyerhoff, J. Ethical Consumption and Social Context: Experimental Evidence from Germany and the United States; University of Bern Social Sciences Working Paper 2014, No 7; 2014. Available online: https://boris.unibe.ch/65756/1/liebe-andorfer-gwartney-meyerhoff-2014.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Juscius, V.; Sneideriene, A. The Research of Social Values Influence on Consumption Decision Making in Lithuania. Econ. Manag. 2014, 18, 793–801. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Jacobson, R.P. Influences of social norms on climate change-related behaviors. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.; Damalas, C.A. Farmers’ perceptions of pesticide efficacy: Reflections on the importance of pest management practices adoption. J. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 35, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Azzahra, F.D.; Suherman, M.S. Pengaruh Social Media Marketing dan Brand Awareness Terhadap Purchase Intention serta dampaknya pada Purchase Decision: Studi pada pengguna layanan Online Food Delivery di Jakarta. Bisnis Manaj. Dan. Keuang. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, T.; Ariza, P. Assessing farmers ’ vulnerability to climate change: A case study in. core.ac.uk 2013.(1):94. Available online: https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/35d36c4d-b8be-3d9b-a266-04d1dabe2abf/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Bekele, F.; Bekele, I. Enviromental and Agricultural Informatics: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. Information Resources Management Association USA Volume III.IG-Global. 2020. Available online: https://dspace.kpfu.ru/xmlui/handle/net/182224 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ali, B.; Baluch, N.; Udin, Z.M. The Moderating Effect of Religiosity on the Relationship between Technology Readiness and Diffusion of E-Commerce. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Jia, F.; Wan, L.; Guo, H. E-commerce in agri-food sector: A systematic literature review. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 439–459. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Chen, C.; Niu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H.; Xue, Z. Risk aversion, cooperative membership and the adoption of green control techniques: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, E.R. Purchase decision analysis through price and product quality. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 1, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlawati; Murniati, S. The Influence of Product Quality and Price on Purchasing Decisions. J. Manag. Res. Stud. 2023, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmiglak-Krajewska, M. Behavioural Aspects of Investment Decisions on Farms. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanović, M. Good agricultural practice in the use of plant protection products. Biljn. Lek. 2022, 50, 195–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Messy, F.A. Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study; OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions; OECD: Paris, France, 2012; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]