Abstract

Background: Toxic chemical adulteration of food is harmful to human health and a major global risk to healthy food consumption. The United Nations declared 2021 as the “International Year of Fruits and Vegetables in an effort to raise public awareness of the nutritional and health benefits of including more fruits and vegetables in a balanced diet”. Although consumers are aware of organic food products, their understanding of the concept is still restricted. Hence, it is paramount to understand their level of awareness and consumption behavior. Methods: Data were captured from 578 samples using a structured questionnaire. Samples were drawn from four districts in Karnataka state of India using a purposive sampling technique. “IBM-SPSS” was used for descriptive analysis, and Smart PLS 4 was adopted to assess the measurement model. Findings: Indian consumers are significantly influenced by health and concern for the environment when buying organic food. Its natural ingredients positively impact customers’ willingness to spend more for organic food. The idea that the natural content of organic food influences millennials’ purchase habits more indirectly than directly is supported by empirical data. Conclusions: With an emphasis on how health concerns influence millennials’ decisions to buy organic fruits and vegetables, this study offers insightful information about customers’ intentions to buy organic food. As the organic food industry develops and fills in current knowledge gaps, the findings are intended to help researchers, food producers, and marketers create focused marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

The organic food industry represents the most thriving segment of the global green market. It is posited that younger consumers, who will be future decision-makers, exhibit greater environmental consciousness than older generations [1]. Furthermore, the global population has already surpassed 7.8 billion individuals. According to forecasts by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the global population is expected to reach 8.5 billion by the end of 2030, 9.7 billion by the end of 2050, and 10.9 billion by the end of 2100 [2]. Consequently, the escalating population drives an increased demand for food, which can exacerbate food security issues and lead to the unsustainable exploitation of planetary resources at an alarming rate.

In response, global efforts have intensified to promote sustainable consumption and production. According to Foresight (2011) [3], sustainable farming is defined as “a method of production using processes and systems that are non-polluting, conserve natural resources and non-renewable energy, are economically effective, are safe for workers, communities, and consumers, and do not compromise the needs of future generations”.

Growing health concerns linked to an increase in chemical poisoning cases worldwide are the main factor driving the growing demand for organic foods. The negative health impacts of chemical pesticides in food products are drawing more and more attention from consumers. Because of their hazardous nature, these pesticides have been linked to hormonal imbalances, cancer, and birth abnormalities. United Nations research claims that every year, over 200,000 people die as a result of pesticides’ detrimental impacts on agricultural crops. As an outcome, consumers are increasingly choosing organic food items (Organic Food Global Market Report 2023) [4].

With a view to provide marketers with a clearer understanding of the impact of their strategies on businesses, organic fruits and vegetables were selected as the specific category of organic food products. Previous research has often used the terms “organic foods” or “organic food products” as umbrella terms encompassing various subjects [5]. Ref. [6] indicate that the millennial generation, being wealthier, is more influenced by concerns for environmental sustainability. Consequently, insufficient research has been conducted on customers within the specific age group called millennials. Scholars [2] have pointed out inconsistencies in the findings. By investigating the buying habits of the millennial age with regard to organic food products, namely organic fruits and vegetables, this study fills a knowledge gap. This field has not received much attention, despite its importance. Consequently, the goal of this study is to learn more about the motivations behind millennials’ desire to buy organic food.

By examining how millennials’ health concerns affect their consumption of organic fruits and vegetables, this study seeks to close the knowledge gap. Key components found through a careful analysis of papers published in respectable journals served as the foundation for this study. In contrast to earlier research that concentrated on particular demographics, including age, this study assesses millennial customers’ general purchasing patterns. Previous studies conducted in industrialized nations have demonstrated that environmental concerns (EC), trust in organic food, and the sensory appeal of organic products significantly influence millennials’ propensity to purchase organic food. However, the impact of millennials’ willingness to pay a premium (WPP) on their purchase intentions remains unclear due to a lack of comprehensive research on this topic.

By investigating how millennials’ health concerns impact their intake of organic fruits and vegetables, the current study aims to fill the information gap. We explore primary elements discovered after carefully examining the research articles in respectable journals. This study set out to evaluate the purchasing habits of millennial customers because earlier research only examined specific demographics, such as age, and failed to identify millennials’ overall purchasing behaviors. A limited number of past research conducted in developed countries with a specific focus on millennial consumers concluded that millennials’ predisposition to buy “organic food” is strongly influenced by sensory appeal, trust in organic food, and environmental concerns. Thus, it is challenging to ascertain how millennials’ purchasing intentions are influenced by their WPP due to the paucity of available literature. Thus, the study results advance our knowledge of the variables affecting millennials’ inclination to buy organic fruits and vegetables.

2. Research Objectives

The research gaps indicated in the previous section are addressed by the study objectives of this research endeavor. Firstly, this research intends to explore the effect of concern for health on Organic buying among millennials. Secondly, it intends to determine how purchasing intention is affected by WPP for organic fruits and vegetables. Finally, this study investigates the mediating role of WPP on the association between natural content and the intention to buy organic products.

The following sections of this research paper are organized as follows: The Hypothesis Development section reviews relevant literature to contextualize existing findings and formulate the proposed conceptual model. The Methodology section provides a detailed account of the study design, sampling strategy, and the development process of the research instruments. The Results section presents the data analysis outcomes, followed by an examination of theoretical and practical implications in the Discussion segment. Finally, the Future Research and Limitations section acknowledges the study’s limitations and suggests potential directions for future research.

3. Review of Literature and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Millennials and the Consumption of Organic Food

In the literature, individuals born between 1982 and 1996 are sometimes referred to as Generation Y or millennials [6]. They are distinguished by their high literacy, frequent internet usage, tech-savvy nature, and social aspirations. According to the Organic Trade Association (2016) [4], they are prepared to pay more for ecological [7] and food safety [8]. In addition to information, millennials are impacted by the perceived value of eating organic food, health advantages, and environmental factors [9]. As a result, marketers who can demonstrate the legitimacy of organic food may be able to convince customers to pay more. Therefore, when analyzing millennials’ views about organic food, it is crucial to take into account the connections between sensory appeal, environmental concern (EC), trust, attitude, WPP, and purchase intention (PI).

3.2. Environmental Concern (EC)

EC is explained as “people’s awareness of the environmental issues and their willingness and support to resolve them” [10]. EC expresses feelings about environmental problems [11]. According to [12], EC has an emotional component that reflects passion, compassion, and awareness of the effects on the environment. According to the findings, EC is a component of attitude toward the environment and mediates attitudes toward green purchasing habits, which in turn affects purchase intention (PI) indirectly [2].

H1.

EC significantly influences towards the health concern.

3.3. Food Safety

One major factor contributing to the rise in the consumption of organic foods has been highlighted as food security. Researchers [13] and some customers think there are less health hazards associated with eating food cultivated organically [14]. Health consciousness and food safety are thus directly intertwined. In this instance, healthcare and customers’ obsession with eating a safer, healthier diet devoid of chemicals that could harm them is linked to safety concerns [15]. The primary justification for purchasing organic food, as mentioned by others [14], is the anticipated advantage to one’s health. Customers think there are fewer risks when consuming organic items than when consuming food that has been chemically treated [16]. Food safety and health consciousness go hand in hand [17]. Customers who are concerned about safety choose foods carefully and avoid chemicals that could be harmful to their health [14] Because they have a favorable impact on people’s perceptions of organic foods as being healthier, safety concerns are a significant factor in PI [18]. Social consciousness and food safety are intertwined [19]. Socially conscious consumers are frequently motivated by values like food safety [20]. Buying organic products is a response to consumer concerns about food safety. When it comes to food safety, consumers trust local manufacturing more [21]. Organic product consumers believe that their actions benefit their families and the neighborhood [22].

H2.

Food safety significantly influences health concerns.

3.4. Natural Content (NC)

According to [23] “Natural content” implies food that has been produced while maintaining the integrity of the raw components by not employing harsh processing methods, artificial coloring, or food additives. Several terms are used to label organic goods, such as “natural”, “local”, “fresh”, and “pure”. Organic food customers typically believe that they are in charge of their health and hence favor foods prepared with natural content [24]. Prior research demonstrates that natural content has a beneficial effect on teenagers’ views and opinions about organic food [25].

The perception that organic products are healthier for consumers is reinforced by their natural attributes [26]. Customers’ health consciousness is associated with the natural content of chemical-free products, which may influence their propensity to purchase organic food [24]. The “natural content” of organic food positively impacts health-conscious consumers [27]. It was concluded that the absence of hazardous substances is a significant factor influencing food selection. The primary objective of consumers purchasing organic food is to avoid synthetic chemicals, additives, and pesticides [28].

H3.

NC in organic food significantly influences consumers’ PI.

H4.

NC in organic food significantly influences consumers’ WPP.

3.5. Willingness to Pay Premium (WPP)

“WPP is defined as an individual’s readiness to pay a higher price to obtain or purchase a certain good or service. It is one of these factors driving the use of organic food”. People who want to live healthier lifestyles and are prepared to pay more for organic food do so because they think that organic items are healthier than conventional food products [7]. Young consumers often have limited financial resources, which can impede their ability to purchase organic products [29]. While environmentally concerned consumers are willing to adopt green practices, they are not always prepared to pay a premium [30]. Contrarily, findings by [1] suggest that consumers have shown a WPP for environmentally friendly products. Given the inconsistent findings regarding this variable in the Indian context, its role in this study warrants further evaluation.

H5.

WPP for organic food significantly influences consumers’ PI.

3.6. Health Concern (HC)

Health concern, which represents accountable decisions that are focused on one’s health, leads people toward adopting healthy behaviors [31]. Due to its higher nutrient content, many customers believe that consuming organic food is healthier. In comparison to conventional diets, green foods boast reduced levels of pollutants and pesticides while offering elevated concentrations of essential nutrients like vitamin C, iron, magnesium, and phosphorus. Incorporating these nutritious options into your diet can promote overall health and well-being [32] “Health-conscious consumers” are more cognizant of their well-being [21]. Individuals are motivated to adopt healthy practices and maintain self-awareness of their health to enhance their well-being, improve their quality of life, and prevent illness [33]. Consequently, health concerns appear to be the primary driver behind the purchase and consumption of organic food in both developed and developing nations [10]. Consumers’ concerns about their health motivate them to adopt an organic eating approach [17]. According to [34], a rising trend among young consumers is the pursuit of healthier food choices, influenced by the acquisition of knowledge about nutrition from their families and educational institutions. Based on this observation, we propose the hypothesis that the increased availability and awareness of healthier food options will positively impact the dietary preferences of young individuals. Thus, it is proposed that

H6.

Consumer’s health concern significantly influences PI.

3.7. Purchase Intention (PI)

Purchase intention (PI) is a construct used to quantify an individual’s commitment to engaging in a specific act or purchasing a particular commodity or service [26]. According [35], “PI is a kind of decision-making that studies the reason to buy a particular brand by consumers”. Previous research on the consumption of organic food has identified several features that help explain why people choose and buy organic food [32]. PI is typically associated with factors such as availability, taste, price premium, quality, nutritional value, health benefits, and environmental effects [10,36].

3.8. Conceptual Framework

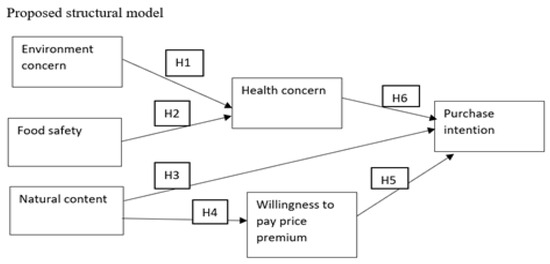

An illustrative representation of the proposed structural model is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proposed Conceptual Framework.

4. Methodology

4.1. Study Design

The primary objective of this research endeavor is to comprehend the underlying health concerns that customers of organic fruits and vegetables have. The quantitative approach is the foundation of this study. To achieve this goal, the conceptual model is tested in this study using a quantitative methodology based on an empirical survey. This allows us to understand the relationship between environmental concerns, food safety, natural content, health concerns, readiness to pay a premium price, and purchasing intention through a survey-based study. In accordance with clause 6 of the circular “Project exempt from submission to IEC issued by the Institutional Ethical Committee on 14 January 2021, this marketing project study was exempt from submission to the Institutional Ethics Committee of Manipal Academy of Higher Education. Consequently, approval from the doctoral advisory committee was obtained. On 11 March 2023, we received approval from my doctoral advisory committee at the Manipal Institute of Management, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India”.

4.2. Participants

Respondents ranged in age from 24 to 40 and were from the top 3 districts of Karnataka, India, which are located in the southern Indian states of Bangalore, Mangalore, and Udupi. When it comes to gross domestic product (GDP), the organic fruit and vegetable sector ranks fourth in India’s economy.

Karnataka State, in India, ranks seventh in terms of “Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP)”, according to the following source: APEDA, FAS New Delhi office study 2021 [8], and was chosen for sampling. Data from the Human Development Index (HDI), which is accessible from the Government of Karnataka [37] (HDI report, FY 2019–2020), were taken into consideration for the major inclusion criterion since they accurately reflect the rate of literacy in the study’s selected area. The highest literacy rate in the region is 88.57% in Mangalore and 86.24% in Udupi. These statistics indicate the level of awareness and understanding regarding organic food in the region. According to research by [27], 58% of Bangaloreans, 47% of Mangaloreans, and 38.97% of Udupi residents purchase organic food products on a monthly basis and are WPP for organic fruits and vegetables. According to an IFOAM and FIBL Organic International report from 2020 [37,38], Karnataka State ranks seventh in the country for organic food consumption; hence, Bangalore was chosen for this study.

4.3. Data Collection Method

Data collection was undertaken at organic food products outlets with an intercept interview method by administering structured questionnaires. Each consumer entering the retail outlet was given a questionnaire and asked to respond to the questionnaire. Since customer data would only be gathered once, the data-collecting strategy used was cross-sectional by nature.

4.4. Scales of Measures

Measurement items on the questionnaire included scales related to the following constructs: food safety (four measurement items from [16,39], natural content (four measurement items from [40], environment concern (five measurement items from [41], WPP (three measurement items from [42,43], health concern (Six measurement items from [44,45] and purchase intention (four measurement items from [10]. A “five-point Likert scale” was employed to measure the dependent and independent variables.

The number of items on the rating scale multiplied by ten determines the sample size [46]. Hence, keeping in mind the above recommendations, accounting for a non-response rate is taken as 10% of the main study and the sample size, i.e., n = 600 for our study. Therefore, the sample size for Bengaluru is 328, Mangalore 142, and Udupi is 108. Hence, the total sample size for the study is 578. The sample size of 578 was considered for the analysis on SMART PLS 4. Hence, we retained 578 samples, and the samples’ collected composition also crossed the limit of 3:1:1 proportions, wherein 328:142:108 data were collected from Bangalore–Mangalore–Udupi, respectively.

5. Data Analysis

5.1. Data Collection

This study’s data were gathered between October 2023 and March 2024. Walk-in customers were encountered for this study. The link of the survey was posted through Google Forms as well as through the storekeeper during his billing process in the organic outlets.

5.2. Results

“Smart PLS 4” was used to estimate the measurement model, and “IBM-SPSS-28” was utilized to describe the demographics of the data. Measurement items with low loadings were excluded from the study after their outer loadings were verified [47]. Following the validation of the study’s model measurements, the researchers employed a bootstrapping strategy with PLS-SEM to assess their research hypotheses.

5.3. Graphical Representation of the Demographic Profile of the Participants

In this study, 51 percent of the participants were males and the majority (36%) of them were from 26 to 30 years age strata. A total of 44 percent of the respondents were postgraduates, with nearly half being married and 33 percent having a monthly income of more than Rs80,000.

5.4. Reliability Assessment

The measurement model’s validity and reliability are evaluated in accordance with [48]. “Convergent validity, discriminant validity, and composite reliability” are the specific indications used to assess internal dependability and consistency [49]. Hence, convergent validity is ascertained using average variance extracted (AVE), while internal consistency is assessed using composite reliability. To evaluate discriminant validity, the researchers use the “Fornell–Larcker” criterion [50]. The internal consistency of the first composite reliability criterion has been evaluated. Table 1 demonstrates that the internal consistent reliability among all of the measurement model’s components is acceptable because the results are over the threshold values for composite reliability, which has a threshold value of 0.60. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability are above 0.70, indicating that the study’s constructs have internal consistent reliability.

Table 1.

Reliability and Validity.

5.5. Discriminant Validity

Measuring a construct’s uniqueness with other measurement model constructs is known as discriminant validity. It gauges how different a build is from the others, and to what degree. The researchers evaluated the discriminant validity using the Fornell–Larcker criterion [50] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Discriminant Validity.

According to [51], values must be less than 0.90 to be considered “discriminant validity” among the constructs. The researchers conclude that there is good validity and reliability among the indicators after evaluating the construct validity, discriminant validity, and reliability. As a result, the next part tests the assumptions and evaluates the structural model.

5.6. Structural Model and Hypotheses Testing

The PLS-SEM approach was used by the researchers to validate the model, and they also looked at the conceptual framework that was created with support from the literature. To calculate the structural model’s route coefficients, the researchers use the PLS-SEM algorithm.

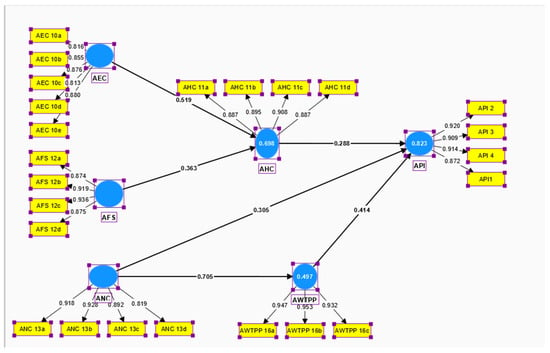

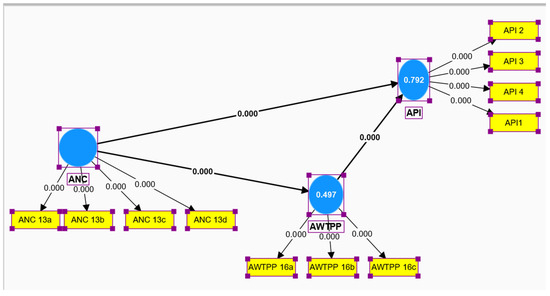

If there is a significant correlation between the constructs, the route coefficient values are not close to zero. The values show a weak link between the constructs if they are close to zero [48]. The bootstrapping technique is used to test the significance level of the link between the components. The structural model evaluation will show the significance level; a t-value greater than 1.96 signifies a meaningful relationship between the constructs. Figure 2 and Figure 3 represent the structural model.

Figure 2.

Structural Model.

Figure 3.

Structural Model Evaluation.

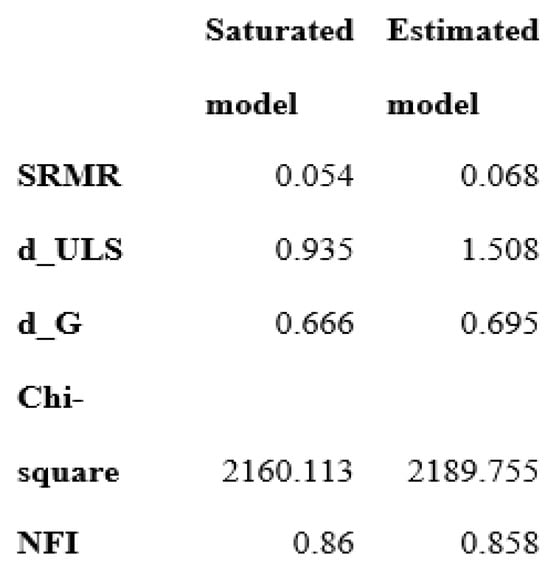

5.7. Model Fit

The structural model has been approved and validated. The goodness-of-fit statistical measures’ enumerated indicators exceeded all acceptable thresholds, as per the recommendations of [48].

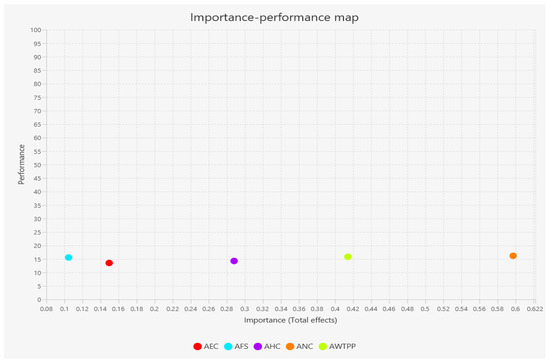

5.8. Importance Performance Map

IPMA enables investigators to consider both the performance and significance of an item. Finding the total impact of constructs (AFS, AEC, ANC, AHC, and AWTPP) in predicting the endogenous construct API is the aim of this investigation. The construct’s relevance is measured by its entire effect, and the performance is based on the average score of the participants, ranging from 0 to 100.

Figure 4.

IPMA Map.

Table 3.

IPMA Analysis.

IPMA of Institutional Efficacy.

6. Results of Hypothesis Testing

The direct effects of AFS, or food safety concern, AEC, or EC and ANC, or natural content on PI (API) were compared in order to test the hypotheses put forward in this study. The outcomes are shown in Table 4 and Table 5. H1 suggested that there is a strong relationship between environmental worry and health concern, which is supported by β = 0.519,t = 8.796, p < 0.01. Food safety, as indicated by H2, has a considerable impact on health concerns and is substantiated by β = 0.363, t = 5.666, p < 0.01.

Table 4.

Hypothesis Testing.

Table 5.

Mediation Results.

Supported by β = 0.292,t = 4.724, p < 0.01, H3 suggested that natural content in organic food had a substantial impact on consumers’ PIs. Supported by data (β = 0.292, t = 4.724, p < 0.01), H4 suggests that natural content in organic food has a considerable impact on customers’ WPP. Hypothesis H5, which states that customers’ PIs are significantly influenced by their WPP for organic food, is supported (β = 0.721, t = 18.206, p < 0.01). H6 posited that a consumer’s health concerns have a considerable impact on their propensity to purchase, and this is corroborated (β = 0.427, t = 6.674, p < 0.01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Natural content in organic food had a substantial impact on consumers’ PIs.

Mediating Role of Natural Content Towards PI

To evaluate the mediating role of natural content on the relationship between WPP and PI, a mediation study was conducted. Table 3’s outcome showed that there was a significant overall impact of natural content on PI (β = 0.459, t = 8.530, p = 0.000) with the mediating variable included.

7. Findings and Practical Implications

The results indicate that customers’ inclinations to purchase “organic food” are influenced by their WPP as well as the food’s natural composition. Moreover, consumers’ perceptions of organic food products are positively impacted by worries about environmental sustainability and food safety. The natural elements found in organic food have a beneficial impact on consumers’ WPP for it. Empirical evidence supports the hypothesis that millennials’ purchasing tendencies are more indirectly influenced by the natural content of organic food than directly.

There are several management implications of the current study. Positively enhancing consumers’ perceptions is the first step towards increasing their intention to purchase. Marketing initiatives play a pivotal role in creating a favorable perception of organic products. By increasing consumer and community awareness of organic food and its advantages—such as its natural content, food safety, and nutrition—as well as how these products contribute to good health, the campaign may help achieve this goal. Understanding the meaning of “organic” in marketing communications depends on the label. Millennials place a high priority on the environmental and sensory aspects of organic food items. Advertisements that emphasize how consuming this organic product protects our ecological or environmental systems could have positive effects and encourage a positive mindset. Consumers are better able to comprehend the benefits of both organic and conventional food products when promotions draw attention to their physical similarities. Third, consumers’ WPP and their level of faith in organic food both influenced their intention to buy. Considering that millennials represent a financially restricted customer base, it is important to recognize the benefits of making a compromise investment in organic food. Therefore, by promoting the idea that “organic certification” is the real seal of legitimacy for items that are organic, it is possible to boost consumers’ trust in organic products. As they gain more knowledge, their WPP for organic food may rise along with their belief in its advantages over conventional food products. Effective segmentation strategies can then be developed and adapted to the appropriate market niche. In particular, millennials are financially conscious, ecologically conscious, and aesthetically pleasing. These segments may prove advantageous in the reorganization of marketing strategy and programs. This research outcome might be used by marketing professionals to develop persuasive ads that highlight the importance of promoting a positive perception of organic food products. If consumers have greater confidence in organic food, they could be prepared to pay a higher price for it.

8. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The current study has some problems that may be resolved in other investigations. First, the sampling technique used in this study may limit the results’ capacity to be generalized. In order to strengthen the study’s findings, several other sample techniques might be used in further investigations. Second, other age groups can be considered to explore WPP and purchase intention. Thirdly, only organic fruits and vegetables were the subject of the current investigation. Therefore, to help marketers better understand how strategy affects their businesses, future studies may focus on a specific product category, such as beverages, etc. Furthermore, conclusions can be reinforced by examining the influence of moderating factors, such as consumer lifestyles. The empirical investigation gap that required care in the previous research gaps of articles has been addressed by the current study.

Author Contributions

K.R.S.: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, and drafting of the manuscript; S.N.: conceptualization, data analysis, drafting the manuscript, and refining the manuscript; V.K.R.: conceptualization and refining of the manuscript; C.A.: data analysis and interpretation of results. R.K.R.: methodology and writing—review & editing. S.V.S.: resources, writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In accordance with clause 6 of the circular “Project exempt from submission to IEC issued by the Institutional Ethical Committee on 14 January 2021, this marketing project study was exempt from submission to the Institutional Ethics Committee of Manipal Academy of Higher Education. Consequently, approval from the doctoral advisory committee was obtained. On 11 March 2023, we received approval from my doctoral advisory committee at the Manipal Institute of Management, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, India”.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Data collection was undertaken using Google Forms and consent has been obtained from the respondents prior to data collection. Prior to sending the Google Forms, respondents were briefed and oral consent was taken from them. Consent was documented while administering the questionnaire to the participant.

Data Availability Statement

The underlying data can be obtained from the corresponding author of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kowalska, A.; Ratajczyk, M.; Manning, L.; Bieniek, M.; Mącik, R. “Young and Green” a Study of Consumers’ Perceptions and Reported Purchasing Behaviour towards Organic Food in Poland and the United Kingdom. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J.; Wyrwa, J.; Jędrzejczak-Gas, J. Practical Implications of the Millennial Generation’s Consumer Behaviour in the Food Market. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foresight UK. Global Food and Farming Futures; Government Office of Science: London, UK, 2011.

- Organic Trade Association. Millennials and Organic: A Winning Combination. 2016. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/millennials-and-organic-a-winning-combination-300332642.html (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Fitriana, G.; Kristaung, R. Factors Influencing Millennials PI. Int. J. Digit. Entrep. Bus. 2020, 1, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, O.; Flores-Zamora, J.; Khelladi, I.; Ivanaj, S. The generational cohort effect in the context of responsible consumption. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1162–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosi, C.; Zollo, L.; Rialti, R.; Ciappei, C. Sustainable consumption in organic food buying behavior: The case of quinoa. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 976–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Rosmann, M.; Beillard, M.J. India—Organic Industry Market Report—2021; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Safeer, A.A.; He, Y.; Lin, Y.; Abrar, M.; Nawaz, Z. Impact of perceived brand authenticity on consumer behavior: An evidence from generation Y in Asian perspective. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2023, 18, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental Consciousness, PI, and Actual Purchase Behavior of Eco-Friendly Products: The Moderating Impact of Situational Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, R.M.; Balasubramanian, P. Understanding the decisional factors affecting consumers’ buying behaviour towards organic food products in Kerala. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 234, 00030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, L.D.; Porter, J.; Lawrence, M. Healthy and environmentally sustainable food procurement and foodservice in Australian aged care and healthcare services: A scoping review of current research and training. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc-Cavlak, O.; Ozdemir, O. Using the theory of planned behavior to examine repeated organic food purchasing: Evidence from an online survey. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2022, 36, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, H. Generational differences in perceptions of food health/risk and attitudes toward organic food and game meat: The case of the COVID-19 crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osaili, T.M.; Obaid, R.S.; Alkayyali, S.A.; Ayman, H.; Bunni, S.M.; Alkhaled, S.B.; Hasan, F.; Mohamad, M.N.; Ismail, L.C. Consumers’ knowledge and attitudes about food additives in the UAE. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, S. Role of consumer health consciousness, food safety & attitude on organic food purchase in emerging market: A serial mediation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102423. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y. Purchasing behavior of organic food among Chinese university students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyie, E.; Gatzweiler, F.; Zurek, M.; Asem, F.E.; Ahiakpa, J.K.; Okpattah, B.; Aidoo, E.K.; Zhu, Y.G. Determinants of Household-Level Food Storage Practices and Outcomes on Food Safety and Security in Accra, Ghana. Foods 2022, 11, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, X.; Khan, M.A.; Mehmood, M.A.; Khan, M.K. Eco-Conscious Consumption in the Climate Change Era: Decoding the Mediating Role of Food Safety and Environmental Concerns between Health Literacy and Take-Out Food Consumption in China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, J.; Trübswasser, U.; Pradeilles, R.; Le Port, A.; Landais, E.; Talsma, E.F.; Lundy, M.; Béné, C.; Bricas, N.; Laar, A. How do food safety concerns affect consumer behaviors and diets in low-and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Takács-György, K. Comparison of Consuming Habits on Organic Food—Is It the Same? Hungary Versus China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetta, L.D.A.; Mucinhato, R.M.D.; Hakim, M.P.; Stedefeldt, E.; da Cunha, D.T. What motivates consumer food safety perceptions and beliefs? A scoping review in BRICS countries. Foods 2022, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, L.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Labesse, M.; Nicklaus, S. Food choice motives and the nutritional quality of diet during the COVID-19 lockdown in France. Appetite 2021, 157, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japutra, A.; Vidal-Branco, M.; Higueras-Castillo, E.; Molinillo, S. Unraveling the mechanism to develop health consciousness from organic food: A cross-comparison of Brazilian and Spanish millennials. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 197–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, L.; Schnettler, B.; Poblete, H.; Jara-Gavilán, K.; Miranda-Zapata, E. Changes in food habits and food-related satisfaction before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in dual-earner families with adolescents. Suma Psicológica 2023, 30, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.W.; Akter, N.; Siddik, A.B.; Masukujjaman, M. Organic foods purchase behavior among generation Y of Bangladesh: The moderation effect of trust and price consciousness. Foods 2021, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, C.S.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, M.; Kaur, P. A review of the influences of organic farming on soil quality, crop productivity and produce quality. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 1884–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, M.; Rodrigues, A.C. A comparison of organic-certified versus non-certified natural foods: Perceptions and motives and their influence on purchase behaviors. Appetite 2022, 168, 105698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacho, F. What influences consumers to purchase organic food in developing countries? Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 3695–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Mou, J.; Meng, C.; Ploeger, A. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Organic Food Continuous PIs during the Post-Pandemic Era: An Empirical Investigation in China. Foods 2023, 12, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonathan, S.; Tjokrosaputro, M. The effect of attitude, health consciousness, and environmental concern on the PI of organic food in Jakarta. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Entrepreneurship and Business Management 2021 (ICEBM 2021), Online, 18 November 2021; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 567–574. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Y.; Khaskheli, A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. How health consciousness and social consciousness affect young consumers PI towards organic foods. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2022, 33, 1249–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Yu, D.; Zubair, M.; Rasheed, M.I.; Khizar, H.M.U.; Imran, M. Health consciousness, food safety concern, and consumer PIs toward organic food: The role of consumer involvement and ecological motives. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211015727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, M.F.; Gaber, H.R.; El Essawi, N. Examining the factors that affect consumers’ PI of organic food products in a developing country. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.R.; Islam, S. Behavioural intention to purchase organic food: Bangladeshi consumers’ perspective. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 754–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Pereira, O. Antecedents of Consumers’ Intention and Behavior to Purchase Organic Food in the Portuguese Context. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- India Organic Food Market. EMR Business Solutions. 2020. Available online: https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/india-organic-food-market (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- India Organic Food Market: Industry Trends, Share, Size, Growth, Opportunity and Forecast 2020–2025. IMARC Services Private Limited. 2020. Available online: https://www.imarcgroup.com/indian-organic-food-market (accessed on 30 October 2018).

- Çabuk, S.; Tanrikulu, C.; Gelibolu, L. Understanding organic food consumption: Attitude as a mediator. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, S.; Lyons, K.; Lawrence, G.; Grice, J. Choosing organics: A path analysis of factors underlying the selection of organic food among Australian consumers. Appetite 2004, 43, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystallis, A.; Chryssohoidis, G. Consumers’ willingness to pay for organic food: Factors that affect it and variation per organic product type. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 320–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royne, M.B.; Levy, M.; Martinez, J. The public health implications of consumers’ environmental concern and their willingness to pay for an eco-friendly product. J. Consum. Aff. 2011, 45, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelidou, N.; Hassan, L.M. The role of health consciousness, food safety concern and ethical identity on attitudes and intentions towards organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, L.; Juric, B.; Bettina Cornwell, T. Level of market development and intensity of organic food consumption: Cross-cultural study of Danish and New Zealand consumers. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thomson, R. The partial least squares approach to causal modeling personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosnow, R.L.; Rosenthal, R. Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).