Exploring the Existence of Moderated Mediation of Attitudes Between Privacy Risk and the Intention to Use Drone Delivery Services

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Intention to Use

2.2. Attitude

2.3. Privacy Risk

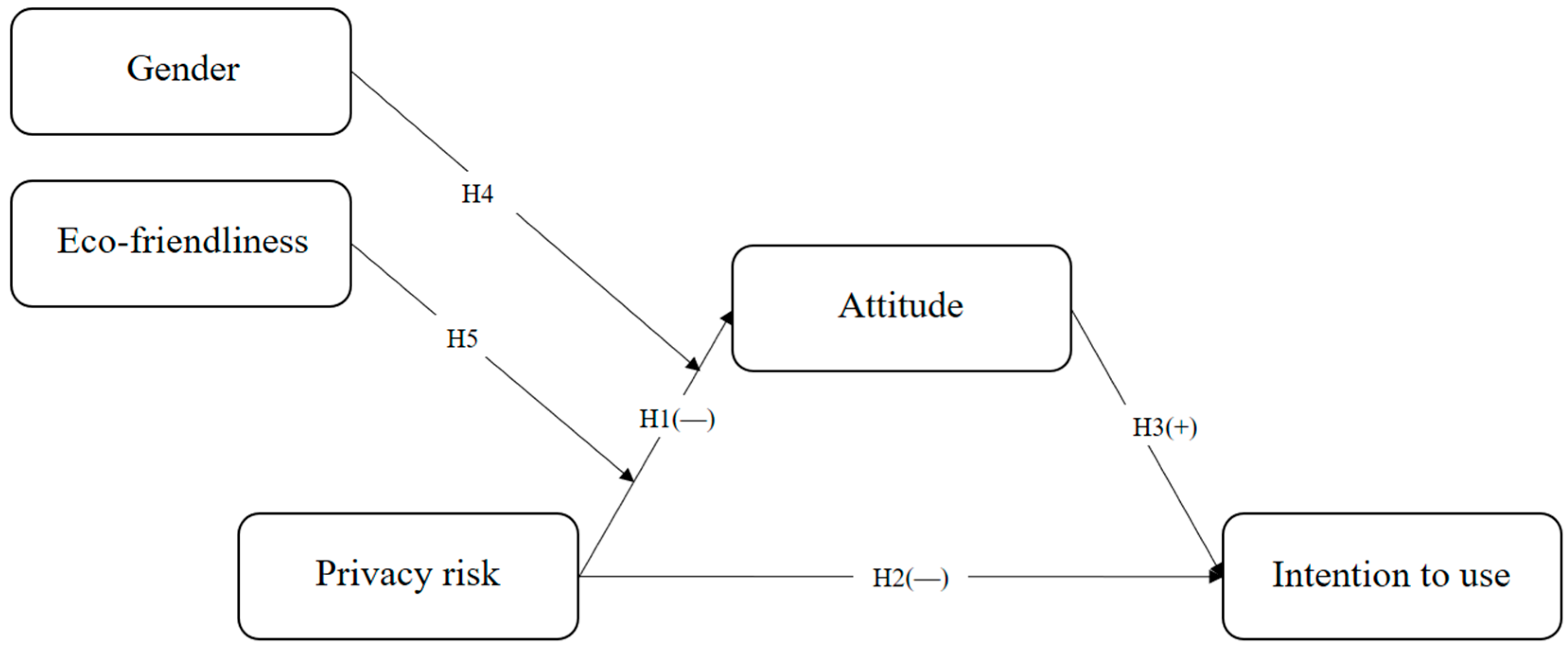

2.4. Hypothesis Development

2.5. Moderating Effects of Gender and Eco-Friendliness

3. Method

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement Items

3.3. Data Collection and Analytic Instruments

4. Results

4.1. Results of Testing the Validity of the Measurement Items

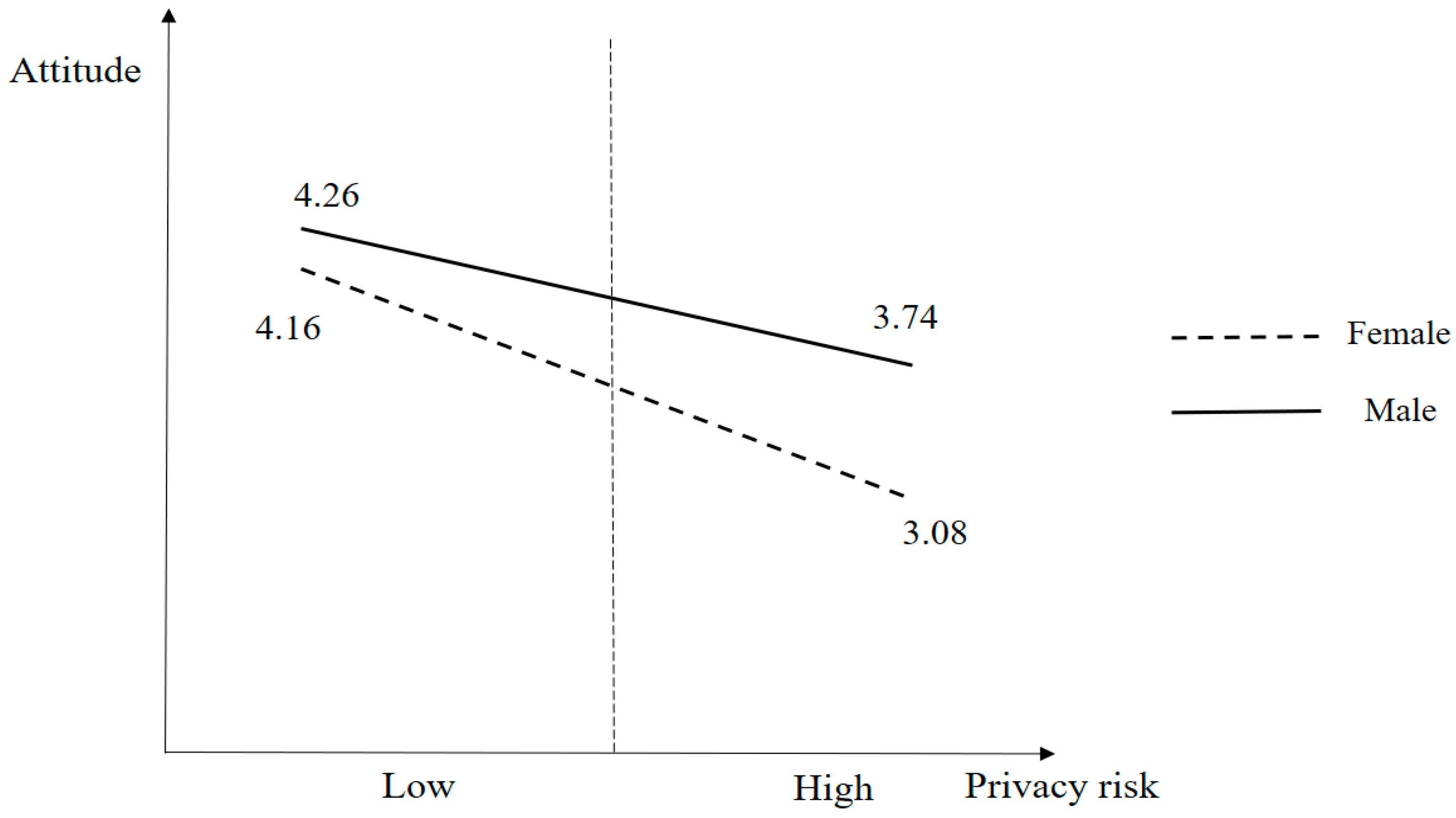

4.2. Results of Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Discussion of the Empirical Findings

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Suggestion for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fortune Business Insights. 2024. Drone Package Delivery Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, by Type (Fixed Wing and Rotary Wing), by Package Size (Less Than 5 Kg, 5–25 Kg, and Above 25–150 Kg), by End-Use (Restaurant & Food Supply, E-Commerce, Healthcare, Retail Logistics & Transportation and Others), and Regional Forecast, 2024–2032. Available online: https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com/drone-package-delivery-market-104332 (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Grand View Research. 2024. GVR Report coverDelivery Drones Market Size, Share & Trends Report Delivery Drones Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report by Component (Hardware, Services), by Application (Agriculture, Healthcare), by Drone Type, by Range, by Payload, by Duration, by Operation Mode, by Region, and Segment Forecasts, 2023–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/delivery-drones-market-report (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Andrejic, M.; Pajic, V.; Stankovic, A. Human resource dynamics in urban crowd logistics: A comprehensive analysis. J. Urban Dev. Manag. 2023, 2, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lee, G.; Yuen, K. Consumer acceptance of urban drone delivery: The role of perceived anthropomorphic characteristics. Cities 2024, 148, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raivi, A.M.; Huda, S.A.; Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Drone routing for drone-based delivery systems: A review of trajectory planning, charging, and security. Sensors 2023, 23, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.J.; Piramuthu, S. Security and privacy risks in drone-based last mile delivery. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, S.; Chen, C.; Ratcliffe, A. Consumers’ perceptions of the environmental and public health benefits of last mile drone delivery. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2024, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Joo, K.; Moon, J. A study on behavioral intentions in the field of eco-friendly drone food delivery services: Focusing on demographic characteristics and past experiences. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarbia, T.; Kyamakya, K. A literature review of drone-based package delivery logistics systems and their implementation feasibility. Sustainability 2021, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, Z.; Solak, S. Improved delivery policies for future drone-based delivery systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 1181–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukkanci, O.; Campbell, J.; Kara, B. Facility location decisions for drone delivery: A literature review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 316, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Chen, C.; Sithipolvanichgul, J. Understanding e-commerce customer behaviors to use drone delivery services: A privacy calculus view. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prisco, A.; Sepe, F.; Nanu, L.; Tani, M. Exploring food delivery app adoption: Corporate social responsibility and perceived product risk’s influence. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 32, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eck, T.; Yim, H. Understanding consumers’ acceptance intention to use mobile food delivery applications through an extended technology acceptance model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higueras-Castillo, E.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.J.; Villarejo-Ramos, Á.F. Intention to use e-commerce vs physical shopping. Difference between consumers in the post-COVID era. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum, S.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Alderbashi, K.; Shwedeh, F.; Aburayya, A.; Al Saidat, M.; Al-Maroof, R. Sustainability model for the continuous intention to use metaverse technology in higher education: A case study from Oman. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Shim, J.; Lee, W. Exploring Uber Taxi Application Using the Technology Acceptance Model. Systems 2022, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansong-Gyimah, K. Students’ Perceptions and Continuous Intention to Use E-Learning Systems: The Case of Google Classroom. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2020, 15, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, A.; Ding, G.; Chin, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Larson, K.; Balakrishnan, H.; Li, M. Drone delivery and the value of customer privacy: A discrete choice experiment with US consumers. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 157, 104391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Footer, K.; White, R.; Park, J.; Decker, M.; Lutnick, A.; Sherman, S.G. Entry to sex trade and long-term vulnerabilities of female sex workers who enter the sex trade before the age of eighteen. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Geçer, E.; Akgül, Ö. The impacts of vulnerability, perceived risk, and fear on preventive behaviours against COVID-19. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 26, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Martins, J.; Mata, P.; Tian, H.; Naz, S.; Dâmaso, M.; Santos, R. Assessing the relationship between market orientation and green product innovation: The intervening role of green self-efficacy and moderating role of resource bricolage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osburg, V.; Yoganathan, V.; Brueckner, S.; Toporowski, W. How detailed product information strengthens eco-friendly consumption. Manag. Decis. 2020, 58, 1084–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, X.; Tang, L. On the introduction of green product to a market with environmentally conscious consumers. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 139, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A.; Ibrahim, B.; Lahuerta-Otero, E.; García de los Salmones, M. Doing good does not always lead to doing well: The corrective, compensating and cultivating goodwill CSR effects on brand defense. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 3397–3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, H.; Xu, H.; Dong, C. Triadic public-company-issue relationships and publics’ reactions to corporate social advocacy (CSA): An application of balance theory. J. Public Relat. Res. 2022, 34, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittka, O.; Hofmann, J.; Johnen, M.; Erfgen, C.; Rezvani, Z. Brand evaluations in sponsorship versus celebrity endorsement. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2023, 65, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzari, A.; Wang, Y.; Prybutok, V. A green experience with eco-friendly cars: A young consumer electric vehicle rental behavioral model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Garg, P.; Singh, S. Pro-environmental purchase intention towards eco-friendly apparel: Augmenting the theory of planned behavior with perceived consumer effectiveness and environmental concern. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2022, 13, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzalonga, F.; Oppioli, M.; Dal Mas, F.; Secinaro, S. Drones in Venice: Exploring business model applications for disruptive mobility and stakeholders’ value proposition. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogah, M. Enhancing Responsible Logistics and Supply Chain Effectiveness: Navigating Current Challenges. In Sustainable and Responsible Business in Africa: Studies in Ethical Leadership; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 249–263. [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi, B.; Senali, M.; Iranmanesh, M.; Khanfar, A.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Annamalai, N.; Naghmeh-Abbaspour, B. Determinants of intention to use ChatGPT for educational purposes: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 4501–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrawad, M.; Lutfi, A.; Almaiah, M.; Elshaer, I. Examining the influence of trust and perceived risk on customers intention to use NFC mobile payment system. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Nhan, P.; Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Determinants of intention to use autonomous vehicles: Findings from PLS-SEM and ANFIS. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golbabaei, F.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Paz, A.; Bunker, J. Individual predictors of autonomous vehicle public acceptance and intention to use: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.S. Customers’ intention to use robot-serviced restaurants in Korea: Relationship of coolness and MCI factors. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2947–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A. Determinants of intentions to use the foodpanda mobile application in Bangladesh: The role of attitude and fear of COVID-19. South Asian J. Mark. 2023, 4, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, D.L. Understanding the attitude and intention to use smartphone chatbots for shopping. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailizar, M.; Almanthari, A.; Maulina, S. Examining teachers’ behavioral intention to use E-learning in teaching of mathematics: An extended TAM model. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Zhang, Q.; Ashfaq, M. Understanding customer attitudes and behaviors towards drone food delivery services: An investigation of customer motivations and challenges. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 32, 1025–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, X.; Lin, Z.B.; Rahman, A. Enhanced pest and disease detection in agriculture using deep learning-enabled drones. Acadlore Trans. AI Mach. Learn. 2024, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J.; Sullivan, G.; Previte, J. Privacy, risk perception, and expert online behavior: An exploratory study of household end users. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2006, 18, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.; Miyazaki, A.; Sprott, D. Reducing online privacy risk to facilitate e-service adoption: The influence of perceived ease of use and corporate credibility. J. Serv. Mark. 2010, 24, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, J.; Breaux, T.D. Empirical measurement of perceived privacy risk. ACM Trans. Comput. Interact. 2018, 25, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornschein, R.; Schmidt, L.; Maier, E. The effect of consumers’ perceived power and risk in digital information privacy: The example of cookie notices. J. Public Policy Mark. 2020, 39, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, G.; Culnan, M. Strategies for reducing online privacy risks: Why consumers read (or don’t read) online privacy notices. J. Int. Mark. 2004, 18, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toch, E.; Wang, Y.; Cranor, L. Personalization and privacy: A survey of privacy risks and remedies in personalization-based systems. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2012, 22, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jiang, H. How do AI-driven chatbots impact user experience? Examining gratifications, perceived privacy risk, satisfaction, loyalty, and continued use. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2020, 64, 592–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Privacy risk assessment of smart home system based on a STPA–FMEA method. Sensors 2023, 23, 4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, H.T. Shaping path of trust: The role of information credibility, social support, information sharing and perceived privacy risk in social commerce. Inf. Technol. People 2023, 36, 683–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, M.; Calvo, M. A privacy threat model for identity verification based on facial recognition. Comput. Secur. 2023, 132, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, A.D.; Fernandez, A. Consumer perceptions of privacy and security risks for online shopping. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Young American Consumers’ Online Privacy Concerns, Trust, Risk, Social Media Use, and Regulatory Support. J. New Commun. Res. 2013, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, S.; Rashid, U.; Te Chuan, L. Acceptance Level of Drone Delivery among Malaysian Consumers. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 232, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Wang, Y.; Sparks, B.; Choi, S. Privacy or security: Does it matter for continued use intention of travel applications? Corn. Hosp. Quar. 2023, 64, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ran, W.; Jiang, S.; Wu, H.; Yuan, Z. Understanding consumers’ behavior intention of recycling mobile phone through formal channels in China: The effect of privacy concern. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 5, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Q.; Kanjanamekanant, K. No trespassing: Exploring privacy boundaries in personalized advertisement and its effects on ad attitude and purchase intentions on social media. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseeh, H.; Jebarajakirthy, C.; Pentecost, R.; Arli, D.; Weaven, S.; Ashaduzzaman, M. Privacy concerns in e-commerce: A multilevel meta-analysis. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1779–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Pasch, T.; Bergstrom, A. Understanding the structure of risk belief systems concerning drone delivery: A network analysis. Technol. Soc. 2020, 62, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, M.; Schaarschmidt, M. What impedes consumers’ delivery drone service adoption? A risk perspective. Arb. Fachbereich Inf. 2020, 2020, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Waris, I.; Ali, R.; Nayyar, A.; Baz, M.; Liu, R.; Hameed, I. An empirical evaluation of customers’ adoption of drone food delivery services: An extended technology acceptance model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, J.; Wickström, A. Constructing a ‘different’ strength: A feminist exploration of vulnerability, ethical agency and care. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 184, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschon, R. Open body/closed space: The transformation of female sexuality. In Defining Females; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kokane, S.S.; Perrotti, L.I. Sex differences and the role of estradiol in mesolimbic reward circuits and vulnerability to cocaine and opiate addiction. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Qiu, H.; Xiao, H.; He, W.; Mou, J.; Siponen, M. Consumption behavior of eco-friendly products and applications of ICT innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 287, 125436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, M.; Adil, M.; Paul, J. An innovation resistance theory perspective on purchase of eco-friendly cosmetics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Could environmental regulation and R&D tax incentives affect green product innovation? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120849. [Google Scholar]

- Luiz, J.M.; Magada, T.; Mukumbuzi, R. Strategic responses to institutional voids (rationalization, aggression, and defensiveness): Institutional complementarity and why the home country matters. Manag. Int. Rev. 2021, 61, 681–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Su, C.; Chen, M. Understanding how ESG-focused airlines reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on stock returns. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 102, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngah, A.; Thurasamy, R.; Rahi, S.; Kamalrulzaman, N.; Rashid, A.; Long, F. Flying to your home yard: The mediation and moderation model of the intention to employ drones for last-mile delivery. Kybernetes 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Yuan, J.; Shahzad, K. Elevating culinary skies: Unveiling hygiene motivations, environmental trust, and market performance in drone food delivery adoption in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 203, 123375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostoj, I. Platform Work as a Source of Satisfaction–Its Merits and Demerits in the Opinion of Poles. Stud. Sieci Uniw. Pogran. 2023, 7, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racat, M.; Plotkina, D. Sensory-enabling technology in m-commerce: The effect of haptic stimulation on consumer purchasing behavior. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2023, 27, 354–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritze, M.P.; Völckner, F.; Melnyk, V. Behavioral Labeling: Prompting Consumer Behavior Through Activity Tags. J. Mark. 2024, 88, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, A.; Stich, L.; Spann, M. The Effect of Delivery Time on Repurchase Behavior in Quick Commerce. J. Serv. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.J.; Lui, C.S.M.; Hahn, J.; Moon, J.Y.; Kim, T.G. How old are you really? Cognitive age in technology acceptance. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Venkatesh, V. Age differences in technology adoption decisions: Implications for a changing work force. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Xie, C. Paradoxes of artificial intelligence in consumer markets: Ethical challenges and opportunities. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Code | Item |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy risk | PR1 | Drone delivery creates privacy risks. |

| PR2 | Drone delivery infringes on privacy. | |

| PR3 | Drone delivery creates privacy problems. | |

| PR4 | Drone delivery brings about privacy encroachment. | |

| Attitude | AT1 | For me, drone delivery is (negative/positive). |

| AT2 | For me, drone delivery is (bad/good). | |

| AT3 | For me, drone delivery is (unfavorable/favorable). | |

| AT4 | For me, drone delivery is (useless/useful). | |

| Intention to use | IU1 | I intend to use a drone delivery service. |

| IU2 | I am going to use a drone delivery service. | |

| IU3 | I will use a drone delivery service. | |

| IU4 | I have an intention to use a drone delivery service. | |

| Eco-friendliness | EF1 | Drone delivery causes less air pollution. |

| EF2 | Drone delivery service is environmentally friendly. | |

| EF3 | Drone delivery service protects the environment. | |

| EF4 | Drone delivery service is eco-friendly. |

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 128 | 31.3 |

| Female | 281 | 68.7 |

| 20–29 years old | 77 | 18.8 |

| 30–39 years old | 153 | 37.4 |

| 40–49 years old | 128 | 31.3 |

| 50–59 years old | 39 | 9.5 |

| Older than 60 years old | 12 | 2.9 |

| Unemployed | 124 | 30.3 |

| Employed | 285 | 67.7 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Less than USD 2500 | 125 | 30.6 |

| Between USD 2500 and USD 4999 | 141 | 34.5 |

| Between USD 5000 and USD 7499 | 60 | 14.7 |

| Between USD 7500 and USD 9999 | 26 | 6.4 |

| More than USD 10,000 | 57 | 13.9 |

| Construct | Code | Loading | Mean (SD) | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy risk | PR1 | 0.876 | 2.89 (1.06) | 0.945 | 0.811 |

| PR2 | 0.928 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.959 | ||||

| PR4 | 0.836 | ||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.957 | 3.80 (1.09) | 0.963 | 0.868 |

| AT2 | 0.955 | ||||

| AT3 | 0.936 | ||||

| AT4 | 0.877 | ||||

| Intention to use | IU1 | 0.922 | 3.33 (1.28) | 0.973 | 0.901 |

| IU2 | 0.967 | ||||

| IU3 | 0.968 | ||||

| IU4 | 0.941 | ||||

| Eco-friendliness | EF1 | 0.777 | 3.84 (0.96) | 0.934 | 0.783 |

| EF2 | 0.901 | ||||

| EF3 | 0.932 | ||||

| EF4 | 0.921 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Privacy risk | 0.900 | |||

| 2. Attitude | −0.471 * | 0.931 | ||

| 3. Intention to use | −0.386 * | 0.830 * | 0.949 | |

| 4. Eco-friendliness | −0.360 * | 0.597 * | 0.544 * | 0.884 |

| Model 1a Attitude | Model 1b Attitude | Model 2a Intention to Use | Model 2b Intention to Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | |

| Constant | 4.986 (22.25) * | 4.834 (18.23) * | −0.393 (−1.81) | −0.403 (−1.71) |

| Privacy risk | −0.346 (−4.56) * | −0.337 (−4.51) * | 0.008 (0.21) | 0.008 (0.22) |

| Gender | 0.339 (3.30) * | 0.349 (1.23) * | ||

| Interaction | −0.206 (−2.26) | −0.209 (−2.25) | ||

| Attitude | 0.973 (26.51)* | 0.973 (26.44) * | ||

| Age | 0.052 (1.07) | 0.003 (0.10) | ||

| F value | 43.17 * | 32.68 * | 448.43 * | 298.23 * |

| R2 | 0.2423 | 0.2445 | 0.6884 | 0.6884 |

| Conditional effect of the focal predictor | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | −0.346 (−4.66) * | −0.337 (−4.66) * | ||

| Female | −0.553 (−9.90) * | −0.547 (−9.74) * | ||

| Index of mediated moderation | Index | Index | ||

| −0.2013 * | −0.2040 * |

| Model 3a Attitude | Model 3b Attitude | Model 4a Intention to Use | Model 4b Intention to Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | β (t value) | |

| Constant | 3.872 (7.22) * | 3.753 (6.90) * | −0.393 (−1.81) | −0.403 (−1.71) |

| Privacy risk | −0.718 (−4.72) * | −0.719 (−4.73) * | 0.008 (0.21) | 0.008 (0.22) |

| Eco-friendliness | 0.229 (1.82) | 0.221 (1.76) | ||

| Interaction | 0.104 (2.83) * | 0.107 (2.89) * | ||

| Attitude | 0.973 (26.51) * | 0.973 (26.44) * | ||

| Age | 0.053 (1.27) | 0.003 (0.10) | ||

| F value | 107.13 * | 80.88 * | 448.43 * | 298.23 * |

| R2 | 0.4425 | 0.4447 | 0.6884 | 0.6884 |

| Conditional effect of the focal predictor | ||||

| Eco-friendliness | ||||

| 3.00 | −0.404 (−7.45) * | −0.398 (−7.34) * | ||

| 4.00 | −0.299 (−7.29) * | −0.291 (−7.05) * | ||

| 5.00 | −0.194 (−3.45) | −0.185 (−3.26) * | ||

| Index of mediated moderation | Index | Index | ||

| 0.1021 * | 0.1041) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, K.-A.; Moon, J. Exploring the Existence of Moderated Mediation of Attitudes Between Privacy Risk and the Intention to Use Drone Delivery Services. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062585

Sun K-A, Moon J. Exploring the Existence of Moderated Mediation of Attitudes Between Privacy Risk and the Intention to Use Drone Delivery Services. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062585

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kyung-A, and Joonho Moon. 2025. "Exploring the Existence of Moderated Mediation of Attitudes Between Privacy Risk and the Intention to Use Drone Delivery Services" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062585

APA StyleSun, K.-A., & Moon, J. (2025). Exploring the Existence of Moderated Mediation of Attitudes Between Privacy Risk and the Intention to Use Drone Delivery Services. Sustainability, 17(6), 2585. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062585