1. Introduction

Desert regions, with their captivating landscapes and unique ecosystems, have gradually become increasingly important as tourist destinations [

1]. However, tourism development in these fragile areas brings significant environmental challenges, the foremost of which is sustainable water resource management [

2,

3]. Desert regions face severe water scarcity, and the increasing demand induced by tourism can exert substantial pressure on limited water resources [

4,

5]. Therefore, addressing water scarcity in desert tourism is critical [

6]. Understanding and promoting responsible water consumption behaviors among tourists is essential for ensuring these destinations’ long-term sustainability.

According to the Statistical Center of Iran (2023), nearly 38 percent of Iran’s population consists of Generation Z (born between the mid-1997s and early 2012s), who will shape the future of the country’s tourism industry. This generation is recognized for its high sensitivity to environmental issues, social consciousness, adoption of sustainable lifestyles, and desire for authentic and sustainable travel experiences [

7,

8]. As Gen Z tourists increasingly visit desert regions in Iran, their attitudes and behaviors towards water conservation can substantially impact the long-term sustainability of these destinations.

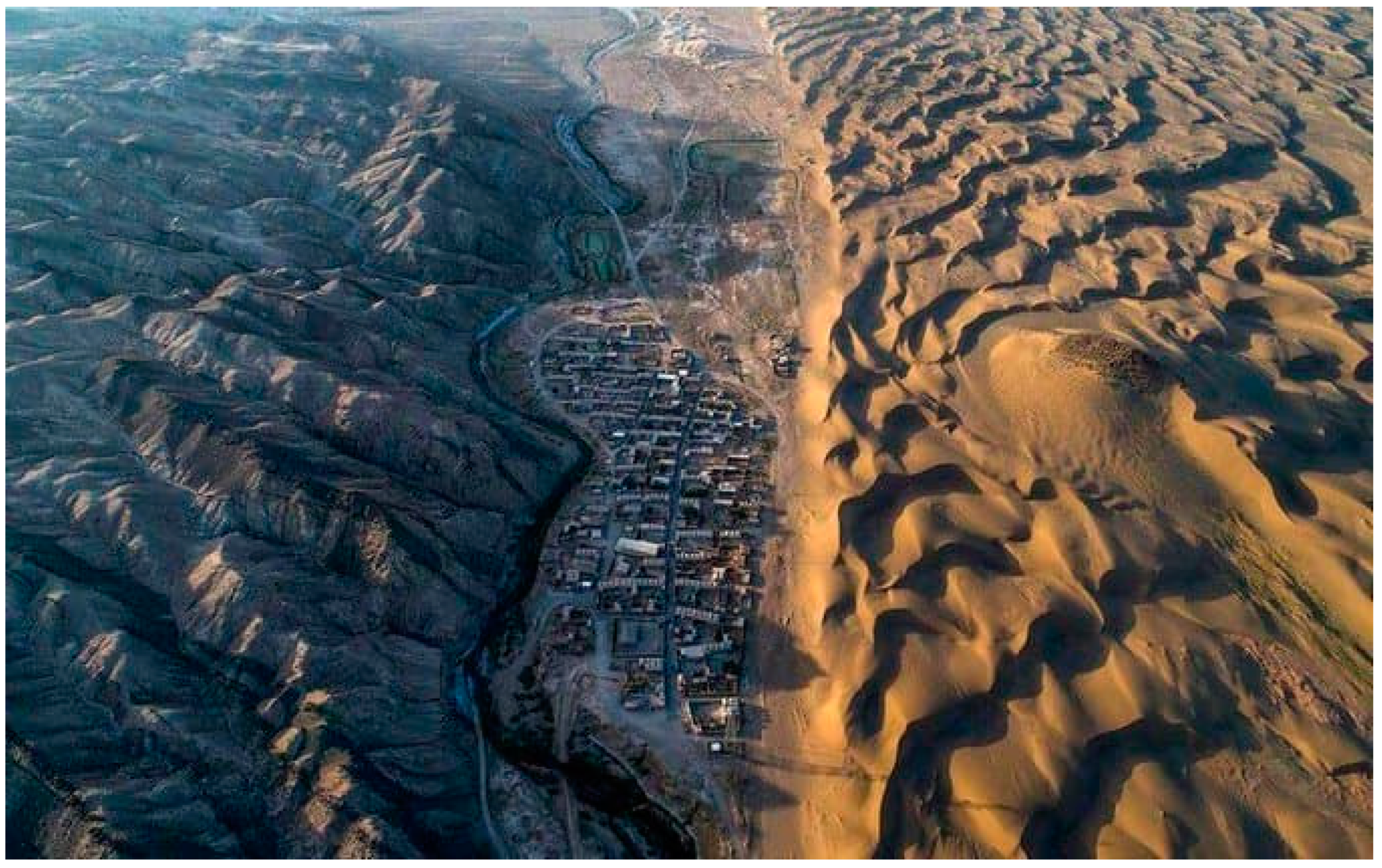

The four Iranian desert villages selected for this study—Qale Bala; Mesr; Abyaneh; and Rezaabad—face major challenges related to water scarcity and sustainable tourism development (

Figure 1). These villages are particularly suitable for examining water conservation behaviors among tourists due to their fragile desert ecosystems, limited water resources, and growing popularity as tourist destinations [

7,

9]. These villages rely on limited groundwater resources, such as wells and qanats (traditional underground water channels), which are increasingly strained due to climate change, population growth, and agricultural demands. The influx of tourists can further exacerbate water scarcity issues, as the increased demand for water in accommodations, restaurants, and other tourist facilities puts additional pressure on the already limited resources. This can lead to conflicts between tourists and residents, who may face difficulties accessing sufficient water for their daily needs and agricultural activities, making it crucial to understand and promote responsible water consumption practices among visitors [

6,

10].

Numerous studies have demonstrated the applicability of NAT in understanding and promoting environmentally responsible behavior, including in the context of water resource conservation [

11,

12,

13]. This theory emphasizes the role of personal norms and their activating factors, such as awareness of consequences, awareness of need, and attribution of responsibility, in shaping pro-environmental behaviors [

14,

15]. However, despite the critical importance of water resource conservation, particularly in fragile areas like desert destinations, evidence suggests a research gap in applying this theory to understanding water-saving behaviors in the context of desert tourism.

The unique challenges of water scarcity in desert environments, coupled with cultural differences, limited resources, and a distinct perception of potential risks compared to other destinations, necessitate a deeper understanding of the factors influencing tourists’ water-saving behaviors in these specific settings [

5,

12,

16]. NAT, with its focus on variables like awareness of consequences, awareness of need, attribution of responsibility, denial of responsibility, and outcome efficacy, provides a suitable theoretical framework for examining the underlying psychological mechanisms of water conservation behaviors [

13,

17,

18]. Moreover, this theory allows for exploring the potential role of emotions and environmental awareness in shaping water conservation behaviors in desert tourism, particularly among Gen Z.

Building upon the established NAT framework, this study makes a novel theoretical contribution by systematically incorporating environmental concerns (ECs) as a key antecedent variable, with specific application to Gen Z tourists in desert regions. The integration of ECs into NAT addresses a critical theoretical gap, as previous research has not fully examined how environmental consciousness interacts with moral activation processes in shaping conservation behaviors. This theoretical extension is particularly relevant for Gen Z, who demonstrate distinct environmental values and consumption patterns compared to previous generations [

1]. Our model examines how ECs interact with core NAT components—personal norms; awareness of consequences; awareness of need; outcome efficacy; and denial of responsibility—to influence water conservation behaviors. This innovative theoretical synthesis provides a more nuanced understanding of the psychological mechanisms driving sustainable behaviors in water-sensitive desert environments, extending beyond traditional NAT applications.

This research addresses significant theoretical and practical gaps in sustainable tourism literature by examining the expanded NAT model’s applicability to water conservation behaviors in Iranian desert villages. While previous studies have investigated water conservation in tourism contexts [

16], few have specifically examined the psychological drivers of Gen Z tourists’ behaviors in water-scarce destinations. Our research empirically tests how the integration of ECs enhances NATs explanatory power for understanding conservation behaviors among this crucial demographic group. The findings contribute to both theoretical advancement and practical application by: (1) validating an extended theoretical framework that better explains Gen Zs environmental behaviors; (2) identifying specific psychological mechanisms that can be targeted in conservation initiatives; and (3) providing evidence-based insights for developing effective water management policies in desert tourism destinations. These contributions are particularly timely given Gen Zs growing influence in the tourism sector and the increasing pressure on water resources in arid regions.

2. Theoretical Background

Water resource management is critical for sustainable development and environmental conservation, particularly in desert and arid regions [

4,

12]. These areas face limited water resources and fragile ecosystems, making sustainable water provision essential for local communities’ economic and social well-being [

19]. Tourism contributes to arid areas’ development but has substantial implications for conserving natural resources, particularly water [

6]. As desert and arid regions become increasingly attractive tourist destinations, promoting responsible behaviors and intelligent use of water resources by tourists and visitors is therefore essential to prevent excessive consumption and ensure sustainability [

5,

19].

While the NAT, originally developed by Schwartz [

20], has demonstrated effectiveness in explaining environmental behaviors across various contexts, its application to tourism-related water conservation in desert regions remains relatively unexplored [

21,

22]. NAT provides a sophisticated theoretical framework for understanding prosocial and moral behavior through the activation of personal norms, positing that internalized moral obligations serve as direct antecedents to prosocial behavior when activated under specific psychological conditions [

21,

23,

24]. The theory’s explanatory power derives from its emphasis on three key psychological prerequisites for norm activation: awareness of consequences, awareness of need, and ascription of responsibility. Awareness of consequences reflects an individual’s recognition of the potential negative outcomes of their actions or inaction, while awareness of need encompasses the cognitive recognition of situations requiring moral consideration. Ascription of responsibility involves the attribution of personal obligation to address identified needs or consequences [

14,

25]. These components operate synergistically through a sophisticated interplay of cognitive and emotional factors that transform latent moral values into behavioral manifestations.

NATs effectiveness stems from its systematic approach to understanding how psychological processes encourage individuals to adhere to norms, values, and ethical principles in their decision-making [

18]. The theory suggests that norm activation occurs through the stimulation of specific factors, including awareness of consequences, perceived needs, outcome efficacy, and responsibility attribution while being potentially inhibited by denial of responsibility [

14,

25]. This theoretical framework has demonstrated particular utility in explaining how individuals navigate ethical decisions by strengthening their commitment to moral norms across various behavioral contexts [

1].

The variables examined in this study, including awareness of consequences, perceived needs, outcome efficacy, responsibility attribution, and denial of responsibility, provide a comprehensive framework to explain water conservation behaviors and personal norms in desert regions. The interaction between these variables contributes to predicting individuals’ behaviors related to water consumption and conservation [

21,

26]. For instance, awareness of needs and consequences can increase outcome efficacy [

27]. Moreover, responsibility attribution and the prevention of responsibility denial play significant roles in strengthening motivation for conservation behaviors [

7,

24].

This study examines the NAT and incorporates the impact of ECs as a catalyst, particularly emphasizing desert areas in developing nations. ECs significantly influence individuals’ attitudes and actions towards water resources and the environment, affecting their decision-making processes. By integrating ECs with NAT, this research aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors that drive water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert regions. This approach enriches the existing theoretical literature and offers practical insights for promoting sustainable water management practices and encouraging environmentally responsible behaviors among tourists in desert tourism destinations.

3. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Norm Activation

Water resource conservation in desert destinations has emerged as a critical issue in environmental sustainability [

5]. Understanding the factors influencing responsible and sustainable water consumption behaviors, particularly among Gen Z tourists, is crucial for promoting conservation practices in these water scarce regions [

28]. NAT has been widely applied to investigate the role of personal norms and their activating factors in shaping pro-environmental behaviors [

18]. Previous studies have highlighted the significant impact of awareness of consequences and contextual effects on personal moral norms among Gen Z tourists [

13,

29,

30,

31]. When individuals of this generation recognize the positive outcomes of adhering to moral norms, they are likelier to exhibit these norms in their tourism behaviors [

17]. Conversely, awareness of the negative consequences of unethical behaviors may deter young tourists from ignoring these norms [

32]. Furthermore, the attribution of responsibility to Gen Z tourists has been identified as a vital factor in shaping and reinforcing their ethical norms [

33]. When this cohort perceives themselves as accountable for fulfilling ethical obligations towards the environment, their likelihood of adhering to norms increases [

34]. This underscores the importance of assigning responsibility and setting expectations for young tourists as moral agents in areas such as water resource conservation in desert regions [

4]. Conversely, denying responsibility can lead to unethical behaviors among Gen Z tourists [

27,

35]. Individuals who avoid accepting responsibility in ethical decision-making and disregard the consequences of their actions may refrain from following moral norms in their tourism behaviors [

17]. Ultimately, the denial of responsibility can negatively impact personal norms among young tourists and weaken their ethical commitments [

36].

Outcome efficacy has been identified as a direct influence on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists [

17,

37]. The perception that one’s actions will lead to positive outcomes, such as rewards for ethical behaviors, encourages this group to adhere to norms in their tourism behaviors [

31]. These rewards can include increased motivation, pride, or other significant benefits for Gen Z [

33,

36].

Based on the above literature, this study proposes five hypotheses to examine the role of awareness of consequences, awareness of needs, situational responsibility attribution, outcome efficacy, and denial of responsibility in shaping water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert destinations. By investigating these variables’ interaction and mutual influence, this research aims to contribute to understanding how individual and social ethical norms towards sustainable water consumption can be established and strengthened among this generation. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1: Awareness of consequences has a direct positive effect on personal norms.

Hypothesis 2: Awareness of needs has a direct positive effect on personal norms.

Hypothesis 3: Situational responsibility attribution has a direct positive effect on personal norms.

Hypothesis 4: Outcome efficacy has a direct positive effect on personal norms.

Hypothesis 5: Denial of responsibility has a direct negative effect on personal norms.

3.2. Environmental Concerns

ECs have emerged as a critical construct in sustainable tourism research, particularly in understanding conservation behaviors among different demographic groups. Recent studies have highlighted how ECs can function as both direct and indirect drivers of pro-environmental behaviors, operating through various psychological mechanisms and normative processes [

38,

39]. In the tourism context, ECs have been shown to influence decision-making processes, behavioral intentions, and actual conservation practices across different settings and cultures [

40,

41]. This is particularly evident in destinations facing environmental challenges, such as water-scarce regions, where tourists’ environmental awareness and concerns can significantly impact resource conservation [

12,

42]. The growing body of research examining ECs in tourism has revealed their multifaceted nature, encompassing not only general environmental awareness but also specific concerns about local ecosystems, resource depletion, and long-term sustainability [

43]. Understanding the role of ECs becomes especially crucial when studying Gen Z tourists, who demonstrate distinctive environmental values and heightened sensitivity to ecological issues compared to previous generations [

1,

12,

14].

Understanding the factors that influence conservation behaviors, particularly among Gen Z tourists, has become a significant research focus [

44]. ECs can profoundly impact the behaviors of this generation concerning water resource conservation in arid areas [

13,

45,

46]. Numerous studies underscore the importance of ECs in shaping conservation behaviors among Gen Z [

15,

31]. Utilizing these concerns as an effective tool to promote sustainable water usage can significantly improve environmental conditions in desert regions, as evidenced by programs in countries like Australia [

47], the United Arab Emirates [

48], the United States [

49], and China [

50]. These countries have implemented initiatives that engage Gen Zs ECs, positively impacting conservation norms and environmental conditions [

36]. Chen and Tung [

51] found that the ECs of young Taiwanese tourists indirectly influence their intention to stay in green hotels by fostering stronger personal norms. Similarly, De Groot and Steg [

52] demonstrated that ECs reinforce personal norms for visiting environmentally responsible museums among Gen Z Korean tourists. Through the lens of norm activation, these studies strengthen environmental values such as concern among this generation and increase awareness of environmental consequences, thereby activating norms [

53,

54].

EC may significantly shape the personal norms of Gen Z tourists regarding water conservation in desert regions. Gen Z individuals with heightened ECs and sensitivity to ecological threats appear more likely to adhere to sustainable water consumption norms [

55]. These concerns can potentially motivate moral discretion in protecting water resources, thereby enhancing this generation’s personal and social ethical norms [

39,

56].

Several studies highlight the relationship between ECs and the tourism behaviors of Gen Z. For example, Rončák et al. [

57] showed that ECs directly increased young Chinese tourists’ intention to save water in hotels. Similarly, Han and Hyun [

58] found that norms surrounding ECs boosted the motivation of Gen Z Korean tourists to engage in energy-saving behaviors during vacations. These findings align with the notion that ECs can directly impact Gen Z tourists’ behaviors, with norm activation playing a fundamental role in driving these changes [

33,

54]. However, some studies suggest that personal norms might moderate the impact of ECs. Packer et al. [

59] demonstrated that the influence of ECs on young Chinese tourists’ intention to visit environmentally friendly restaurants was mediated entirely by personal norms. This indicates that mediating factors, such as personal norms, may influence the relationship between ECs and the behaviors of Gen Z tourists. Thus, further research is needed to explore moderators and cultural factors that shape how ECs motivate conservation behaviors in this generation [

55].

The existing research supports the positive relationship between ECs, personal norms, and water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists. Nevertheless, gaps remain concerning contextual and cultural factors that may influence the activation of norms and the direct impact of environmental values on behaviors. Future studies should focus on identifying these determinants among Gen Z tourists. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 6: ECs have a direct positive effect on tourists’ personal norms.

Hypothesis 7: ECs have a direct positive effect on tourists’ water conservation behavior.

3.3. Personal Norms, Guilt, and Pride

Research attention has increased significantly in water resource conservation behaviors within tourism, mainly focusing on Gen Z [

32,

44]. This focus has led to numerous studies and investigations testing theoretical models, such as the norm activation model, to understand and analyze the environmental behaviors of tourists [

39,

60]. The norm activation model posits that personal norms, especially among young Gen Z tourists, are fundamental in determining social behaviors, particularly in conserving natural resources. This concept has been supported by multiple studies [

53]. Personal norms refer to an individual’s ethical commitment to performing or refraining from specific actions, particularly among Gen Z tourists who exhibit high sensitivity to environmental issues [

20,

25].

According to the norm activation model, the personal norms of Gen Z tourists are triggered by awareness of consequences and assigned responsibilities, leading to pro-environmental behaviors. These behaviors may also be influenced by anticipated positive and negative emotions, such as pride or guilt, which are significant motivators for this generation [

51,

61]. Numerous studies have utilized the norm activation model to interpret Gen Zs tourism behaviors related to water conservation. For instance, Müller et al. (2018) [

62] demonstrated that the personal norms of young tourists directly increase their willingness to accept water-saving measures in hotels, highlighting the behavioral impact of perceived ethical commitment in this group.

Various studies have examined the relationships between personal norms, emotions, and behaviors of tourists and shown that personal norms significantly influence the behaviors and emotions of this generation [

34]. Harland et al. [

25] found that the personal norms of young British tourists significantly impact their tourism behaviors and predict behaviors such as environmental support, influenced by factors like pride and guilt. These results suggest that Gen Z individuals who value healthy and sustainable environmental personal norms are more likely to engage in positive environmental behaviors [

43].

Studies on the norm activation model generally provide empirical support for the hypothesized positive relationships between the personal norms of Gen Z tourists, pride emotion/guilt, and water conservation actions. However, it is important to note significant gaps based on contextual and cultural differences within this generation. Testing hypotheses among diverse Gen Z tourist populations can enhance our understanding of promoting sustainable behaviors globally, including water resource conservation in desert environments. Therefore, we suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 8: Tourists’ personal norms directly affect their pride in water resource conservation.

Hypothesis 9: The personal norms of tourists directly affect the guilt emotion in water resource conservation.

Hypothesis 10: Tourists’ pride emotion has a direct positive effect on water resource conservation behavior.

Hypothesis 11: Tourists’ guilt emotion has a direct positive effect on water resource conservation behavior.

Hypothesis 12: The personal norms of tourists have a direct positive effect on water resource conservation behavior.

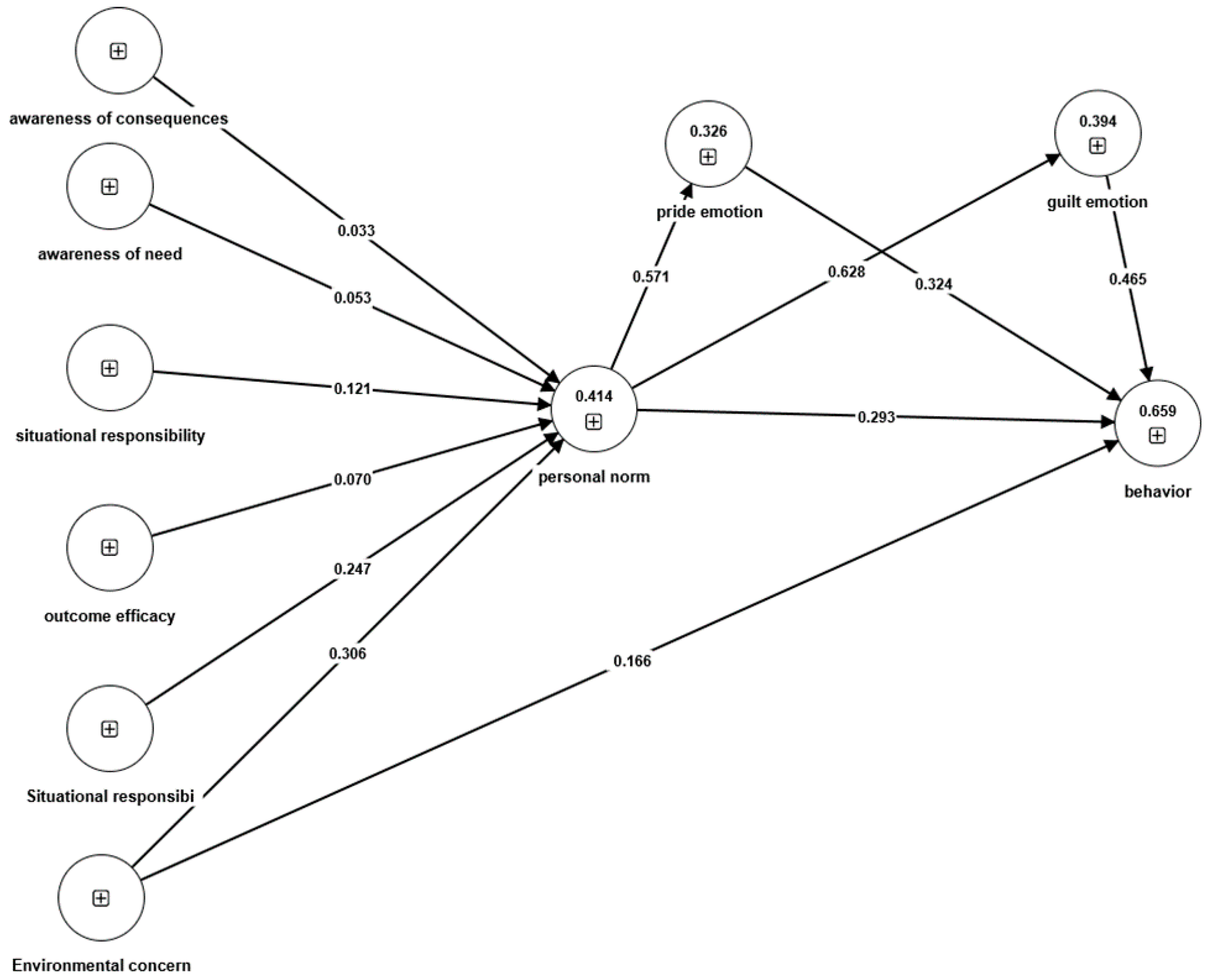

This research presents a comprehensive conceptual model based on the NAT to understand better water resource conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists visiting desert villages in Iran (

Figure 2). The core of the model revolves around the central role of personal norms in shaping pro-environmental behaviors, which are activated by factors such as awareness of consequences, awareness of needs, and attributed responsibilities. The study’s hypotheses 1 to 4 explore the intricate relationships between these variables and personal norms, aiming to provide a robust theoretical foundation for the proposed model.

In a significant theoretical advancement, the model has been extended to incorporate the growing importance of ECs among Gen Z tourists, addressing a notable gap in the existing literature. This extension positions ECs as a key precursor to both personal norms and water conservation behaviors, with hypotheses 6 and 7 investigating the impact of this variable on these critical outcomes. Furthermore, the model includes additional components such as outcome efficacy, denial of responsibility, pride, and guilt, which are potential motivational factors. Hypotheses 4, 5, and 8 to 12 test the relationships between these variables and their influence on water conservation behaviors, providing a comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay of psychological and emotional factors in shaping pro-environmental actions.

Overall, the conceptual model integrates key psychological and emotional variables to offer a holistic view of the factors driving water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists. This approach not only enhances the explanatory power of NAT in this specific context but also highlights the potential importance of tailoring conservation strategies to the specific characteristics and values of Gen Z. By doing so, the model provides a valuable framework for developing targeted interventions that effectively promote sustainable tourism practices among this increasingly significant demographic.

4. Methodology

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed to test the hypotheses and evaluate the proposed theoretical framework. Several methodological considerations justified this analytical choice. First, this study’s primary objective was to examine the predictive relationships between ECs, NAT components, and water conservation behaviors, making PLS-SEM particularly suitable due to its prediction-oriented nature [

63]. Second, our extended NAT model represents a complex 330-structural model with multiple mediating and direct relationships between constructs, which PLS-SEM can effectively handle [

64]. Third, preliminary data analysis revealed non-normal distribution patterns in several variables (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test,

p < 0.05), and PLS-SEM is robust against such violations of normality assumptions [

65]. Although our measurement model consists entirely of reflective indicators, PLS-SEMs capability to handle complex structural relationships while maintaining statistical power made it an appropriate choice for our analysis [

63]. Additionally, while our sample size (

n = 330) exceeded minimum requirements, PLS-SEMs ability to handle complex models with relatively smaller samples provided additional methodological assurance. The analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 4.0.9.6 software, following the systematic evaluation procedure recommended by current methodological guidelines [

66].

4.1. Measurement Scale and Questionnaire Design

We utilized reflective indicators to measure nine constructs in this research. These constructs, including awareness of consequences, awareness of need, situational responsibility, outcome efficacy, denial of responsibility, ECs, personal norms, pride, and guilt, were assessed using a five-point Likert-type scale that ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The items measuring these constructs were adapted from pertinent literature on environmental psychology, sustainable tourism, and the NAT. The complete list of measurement items and their corresponding sources is provided in

Appendix A.

Water conservation behavior, the main dependent variable, was measured using four items that assessed the extent to which tourists engaged in specific water-saving activities during their visit to the desert villages. These items were developed based on the context of the study and previous research on water conservation practices in tourism [

16,

67]. Respondents were asked to indicate their level of engagement in these behaviors using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all” to “to a great extent”.

Several procedural remedies were employed to reduce common method bias associated with self-report surveys. First, the anonymity of the respondents was assured, and the research objectives were clearly stated in the introductory part of the questionnaire. Second, the order of the measurement items for the independent, dependent, and moderating variables was counterbalanced to minimize potential order effects. Finally, the questionnaire was designed to use clear and concise language, avoiding ambiguous or double-barreled questions that could confuse the respondents.

The demographic variables collected in the first section of the questionnaire, such as age, gender, education level, and travel frequency, were included as control variables in the structural model. This approach allows for a more precise examination of the relationships between the main constructs while controlling for the potential influence of these demographic factors on water conservation behaviors and psychological processes.

4.2. Data Collection and Demographics

A quantitative approach was adopted to investigate water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert regions of Iran. The study focused on four desert villages: Qale Bala, Mesr, Abyaneh, and Rezaabad. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire administered to Gen Z tourists born between 1997 and 2012 who visited these villages between April and July 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, with parental consent secured for those under 18 years of age.

A two-stage sampling approach was implemented to ensure systematic and unbiased data collection. In the first stage, stratified sampling was used to identify Gen Z tourists (born between 1997 and 2012) from the general tourist population in the selected villages. This age-based stratification was essential to focus specifically on the target demographic group. In the second stage, systematic random sampling was employed within the Gen Z stratum, where trained research assistants approached every 5th tourist at key tourist locations in each village (e.g., main attractions, accommodations, and gathering spots). This systematic approach helped mitigate potential response biases and reduce sampling subjectivity. The required sample size was determined using G*Power software, which indicated a minimum requirement of 150 respondents for achieving a statistical power of 0.80 with a medium effect size (f2 = 0.15) at α = 0.05. However, we aimed for a larger sample to ensure robust analysis and account for potential invalid responses. Due to the geographical dispersion of the selected villages (Qale Bala, Mesr, Abyaneh, and Rezaabad) and the specific age requirements, the data collection process was conducted over an extended period from April to July 2023. Tourists were briefed about the research objectives and invited to participate voluntarily. From the 400 questionnaires collected, 330 were deemed valid after screening out incomplete or inconsistent responses (e.g., questionnaires with uniform responses across all items). The questionnaire was initially developed in English and then underwent a rigorous back-translation process to ensure accuracy and cultural appropriateness. First, it was translated into Persian by two bilingual tourism researchers. Then, it was independently back-translated to English by two different bilingual experts. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved through consensus. Participants completed the questionnaires in Persian, and the responses were later translated back into English for analysis.

The demographic characteristics of the respondents show that 55% were female and 45% were male. All participants were between 11 and 26 years old, falling within the age range of Gen Z (born between 1997 and 2012). Regarding education, 60% had a bachelor’s degree, 25% had a master’s degree, and 15% had a high school diploma or lower. Most respondents (72%) reported traveling to desert destinations once or twice a year, while 28% stated they visit these areas more frequently.

4.3. Control for Method Biases

To address potential common method bias concerns in examining water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists, we employed both procedural and statistical remedies. Procedurally, we implemented several ex-ante measures during questionnaire design and data collection. First, we used clear and specific language in items measuring NAT constructs and water conservation behaviors, with all constructs measured on a five-point Likert scale. Second, we randomized the order of NAT components (awareness of consequences, awareness of need, situational responsibility) and EC items to minimize response patterns. Third, we assured Gen Z respondents of their anonymity and emphasized that their honest responses would help understand water conservation in desert tourism. As a statistical remedy, we conducted Harman’s single-factor test, where the unrotated principal component analysis revealed that the first factor accounted for only 28.4% of the total variance, suggesting that CMB is not a significant concern in our NAT model testing. Additionally, the marker variable technique analysis showed minimal correlations between the marker variable and our NAT constructs (average r = 0.11), further supporting the validity of our findings regarding water conservation behaviors.

We implemented several methodological safeguards specific to our research context to mitigate social desirability bias in water conservation self-reports among Gen Z tourists. First, we utilized neutral phrasing in our five-point Likert scale items when measuring ECs and NAT variables, such as “I consider the water scarcity issues in desert regions” rather than “I care deeply about water conservation”. Second, for water conservation behaviors, we focused on specific actions (e.g., frequency of water-saving practices during desert visits) rather than general environmental attitudes. Third, we included reverse-coded items across NAT components to detect response patterns and maintain participant engagement. The data collection was conducted by research assistants trained specifically in desert tourism research, who emphasized the study’s focus on understanding rather than judging water conservation practices. A pilot test with 30 Gen Z tourists in similar desert destinations helped refine our measurement items and identify any potential biases in responses to NAT and EC items before the main data collection phase.

4.4. Measurement Models

Table 1 presents a comprehensive assessment of model fit indices for both the original NAT and extended models incorporating ECs. The analysis employs multiple widely accepted fit indices to ensure robust evaluation of model adequacy [

63]. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values for both models (0.070 and 0.063, respectively) fall well below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating a good absolute fit, with the extended model demonstrating a marginally superior fit. The Normed Fit Index (NFI) values exceed the conventional threshold of 0.90 for both models (0.940 and 0.952), suggesting strong incremental fit characteristics. The RMS_theta values, which assess outer model residual correlations, remain within acceptable parameters (≤0.12) for both models (0.080 and 0.086), though slightly higher in the extended version due to increased model complexity. The metrics of geodesic distance (d_G) and unweighted least squares discrepancy (d_ULS) demonstrate adequate model fit, with values significantly above the minimum threshold of 0.05. Notably, both the Chi-square/df ratios (2.45 and 2.31) and RMSEA values (0.064 and 0.058) indicate good model parsimony and approximate fit, with the extended model showing superior performance across most indices. The collective analysis of these fit indices provides strong empirical support for both models while consistently demonstrating enhanced fit characteristics in the extended model. This improvement in model fit indices substantiates the theoretical value of incorporating ECs into the NAT framework for understanding water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert destinations. The comprehensive fit assessment suggests that the extended model offers superior explanatory power while maintaining an appropriate model (parsimon Becker et al. 2023) [

64].

Based on the research objectives of testing the application of the NAT in explaining water conservation behaviors of Gen Z tourists in desert regions of Iran, the fit of the measurement model was assessed in two stages using reliability and validity criteria for reflective constructs.

The reflective constructs were assessed for reliability and convergence validity in the initial phase using factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and composite reliability. All items exhibited factor loadings greater than 0.4, and Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability values for all variables surpassed the 0.7 threshold, signifying the suitability of the questions and the satisfactory reliability of the variables. In addition, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all constructs were higher than 0.5, confirming their convergent validity. In the second stage, the discriminant validity of the constructs was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The results showed that the square root of the average variance extracted for each construct was greater than its correlation values with other constructs, confirming the adequate discriminant validity of the measurement model.

Overall, the results of the measurement model fit assessment in both the original and extended NAT models provide evidence supporting the reliability and validity of the studied variables. The appropriate values of factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and composite reliability confirm the convergent validity of the reflective variables, while the results of the discriminant validity test verify the distinction between the concepts measured by different constructs. Therefore, given the acceptable fit of the measurement models, it is assumed that the reflective variables employed are suitable proxies for the latent concepts under study, and one can rely on them to test the research hypotheses and examine the relationships between the variables of the conceptual model (

Table 2).

The Fornell-Larcker criterion was used to evaluate whether the constructs were distinct. The results showed that the square root of the average variance extracted for each construct exceeded its correlation values with other constructs, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity. This suggests that the measured variables correspond to different theoretical concepts. The analysis confirms that awareness of consequences, needs, situational responsibility attribution, outcome efficacy, denial of responsibility, ECs, personal norms, pride, guilt, and water conservation behavior are conceptually different. This discriminant validity establishment enhances the measurement model’s overall validity and supports the subsequent interpretation of the structural relationships among these variables in understanding water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert regions (

Table 3).

5. Hypothesis Testing

To comprehensively evaluate the role of ECs in water conservation behaviors, we tested both the original NAT model and our extended model. This dual-model testing approach serves several analytical purposes. First, it provides a baseline assessment through the original NAT model, allowing us to validate the fundamental relationships between awareness of consequences, awareness of need, situational responsibility, and water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists. Second, comparing the two models enables us to quantify the incremental explanatory power gained by incorporating ECs into the NAT framework, as evidenced by the improvement in R² values from 0.645 in the original model to 0.659 in the extended model. Third, this comparative approach helps establish the discriminant validity of ECs as a distinct construct from traditional NAT components while demonstrating its complementary role in explaining water conservation behaviors. Additionally, testing both models allows us to examine whether the inclusion of ECs affects the stability and significance of original NAT relationships, thereby providing insights into the robustness of the theoretical framework in the context of desert tourism.

5.1. Original Model

The results of testing hypothesis one showed that awareness of consequences has a positive but non-significant effect on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.070, T = 1.773,

p = 0.076). The results of testing hypothesis two indicated that awareness of needs has a positive but non-significant effect on the personal norms of this group (β = 0.058, T = 1.182,

p = 0.273). The results of testing hypothesis three revealed that situational responsibility attribution has a positive and significant effect on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.154, T = 2.269,

p = 0.023). The results of testing hypothesis four demonstrated a positive but non-significant effect of outcome efficacy on the personal norms of this group (β = 0.092, T = 1.802,

p = 0.072). The results of testing hypothesis five showed that denial of responsibility has a negative and significant effect on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = −0.389, T = 7.735,

p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis eight indicated a positive and significant effect of the personal norms of this group on their pride emotion (β = 0.571, T = 18.946,

p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis nine revealed that the personal norms of Gen Z tourists have a positive and significant effect on their guilt emotion (β = 0.628, T = 26.807,

p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis ten demonstrated a positive and significant effect of Gen Z tourists’ pride on their water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.267, T = 6.848,

p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis eleven showed that personal norms positively and significantly affect this group’s water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.281, T = 7.585,

p < 0.001). Additionally, the results of testing hypotheses six and seven indicated a positive and significant effect of ECs on personal norms (β = 0.306, T = 7.658,

p < 0.001) and water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.166, T = 2.036,

p < 0.001) among Gen Z tourists (

Figure 3).

5.2. Extended Model

The results of testing hypothesis 1 showed that awareness of consequences has a positive but non-significant effect on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.033, T = 1.787, p = 0.068). The results of testing hypothesis 2 indicated that awareness of needs has a positive but non-significant effect on the personal norms of this group (β = 0.055, T = 1.203, p = 0.061). The results of testing hypothesis 3 revealed that situational responsibility attribution has a positive and significant effect on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.121, T = 2.126, p = 0.011).

The results of testing hypothesis 4 demonstrated a positive but non-significant effect of outcome efficacy on personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.070, T = 1.724, p = 0.080). The results of testing hypothesis 5 showed that denial of responsibility has a negative and significant effect on the personal norms of this group (β = −0.274, T = 6.658, p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis 6 indicated a positive and significant effect of ECs on the personal norms of Gen Z tourists (β = 0.306, T = 7.658, p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis 7 revealed that ECs positively and significantly affect this group’s water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.166, T = 2.036, p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis 8 demonstrated a positive and significant effect of the personal norms of Gen Z tourists on their pride emotion (β = 0.571, T = 18.658, p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis 9 showed that the personal norms of this group have a positive and significant effect on their guilt emotion (β = 0.628, T = 19.354, p < 0.001). The results of testing hypothesis 10 indicated a positive and significant effect of Gen Z tourists’ pride on their water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.324, T = 7.587, p < 0.001). Testing hypothesis 11 revealed that personal norms positively and significantly affect this group’s water resource conservation behavior (β = 0.293, T = 2.875, p < 0.001). These results suggest that ECs and personal norms are key in shaping water resource conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in Iranian desert regions.

The results show that the R2 value for the original model is 0.645, indicating that the model explains 64.5% of the variance in water conservation behavior among Gen Z tourists. In the extended model, which incorporates ECs, the R

2 value increases to 0.659, suggesting that this model accounts for 65.9% of the variance in the dependent variable. The higher R-squared value in the extended model demonstrates that the inclusion of ECs enhances the explanatory power of the NAT in understanding water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in Iranian desert villages (

Table 4 and

Figure 4).

6. Discussion

The findings of this research offer important perspectives into the elements that impact water conservation actions among Generation Z travelers in villages located in the Iranian desert. Analyzing the connections between crucial factors of the NAT and ECs adds to a more profound comprehension of the psychological processes that drive environmentally friendly behaviors within the framework of desert tourism.

The initial model, which was built on the NAT, encompassed variables such as awareness of consequences, awareness of needs, situational responsibility attribution, outcome efficacy, and denial of responsibility. The expanded model included ECs as an additional factor to gain deeper insights into the development of water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists. Comparing the outcomes of the original and expanded models provides valuable insights. In both models, situational responsibility attribution had a significantly positive impact on personal norms, supporting previous studies’ conclusions. This highlights the significance of nurturing a sense of responsibility to encourage sustainable water usage practices among Gen Z tourists.

However, the non-significant effects of awareness of consequences and awareness of needs on personal norms in both models contrast with some previous studies [

37,

43]. This discrepancy suggests that the factors influencing personal norms may vary across different settings and generational cohorts. Such variation highlights the need for further research to understand the contextual and demographic factors that influence the effectiveness of these variables.

The extended model, which included ECs, provided additional insights into the formation of water conservation behaviors. The significant positive effect of ECs on both personal norms and water conservation behavior is consistent with previous findings (Han & Hyun, [

58]; Shen et al. [

15]; Rončák et al. [

57]. This highlights the need to cultivate environmental awareness and concern among Gen Z tourists to encourage sustainable tourism practices. In both models, the significant positive effects of personal norms on pride emotion and guilt, as well as the direct positive effects of pride and guilt on water conservation behavior, provide new insights into the emotional dimensions of pro-environmental behavior among Gen Z tourists. These findings suggest that moral emotions motivate sustainable water consumption practices.

Furthermore, the significant negative effect of denial of responsibility on personal norms in both models aligns with previous findings (Schönherr & Pikkemaat) [

32] Zhang et al. [

24] Gao et al. [

27], underscoring the importance of counteracting denial and promoting personal responsibility to encourage sustainable water consumption among Gen Z tourists. Comparing the original and extended models reveals that including ECs enhances the NATs explanatory power in understanding water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists. The extended model provides a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological factors driving pro-environmental behaviors in the context of desert tourism.

This study’s findings corroborate and extend previous research on water conservation and environmental behaviors among Gen Z tourists. The results highlight the importance of targeting personal norms, ECs, and moral emotions in interventions to promote sustainable water consumption practices among this generation. The inclusion of ECs in the extended model offers valuable insights for tourism stakeholders in developing targeted strategies to promote sustainable tourism practices in desert destinations. Specifically, these findings suggest that efforts to enhance environmental awareness and responsibility among tourists can lead to more effective water conservation initiatives, ensuring the sustainability of fragile desert ecosystems.

This study underscores the need for tailored approaches that consider the unique psychological and emotional drivers of Gen Z tourists to foster pro-environmental behaviors effectively. Future research should continue to explore the contextual and cultural factors that influence these dynamics, aiming to develop more robust and inclusive models for promoting environmental sustainability in tourism.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several significant theoretical contributions to sustainable tourism literature and environmental behavior research. First, we advance the theoretical understanding of NAT by systematically integrating ECs as distinct antecedent variables. While previous studies have examined NAT components in tourism contexts, our research demonstrates how ECs interact with and enhance the traditional NAT framework. This theoretical extension is particularly significant as it shows that ECs serve as direct predictors of conservation behavior and as activators of personal norms, thereby enriching our understanding of the psychological mechanisms underlying pro-environmental behaviors.

Second, our research contributes to generational theory in tourism by empirically validating the distinctive characteristics of Gen Zs environmental behavior patterns. The findings reveal that Gen Z tourists’ response to water conservation initiatives is uniquely mediated through cognitive (ECs) and emotional (pride and guilt) pathways, extending previous theoretical frameworks primarily focused on rational decision-making processes. This insight advances our understanding of how generational characteristics influence the effectiveness of environmental behavior models.

Third, we contribute to the theoretical discourse on destination-specific environmental behaviors by demonstrating how context (desert tourism) moderates the relationship between ECs and conservation actions. This finding extends existing theory by showing that the physical environment’s vulnerability can enhance the salience of ECs in activating personal norms. This context-specific theoretical advancement helps explain why certain environmental behaviors may be more pronounced in particular tourism settings.

Fourth, our research expands the theoretical understanding of moral emotions in environmental behavior by demonstrating their dual role as both outcomes of personal norms and antecedents of conservation actions. This finding enriches existing theoretical frameworks by highlighting the complex interplay between moral norms, emotions, and behavioral outcomes in tourism contexts, particularly among generationally distinct groups like Gen Z.

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

The empirical findings of this study offer substantial implications for destination management and policy formulation in desert tourism contexts. The results demonstrate the necessity of implementing evidence-based interventions that address both the psychological and behavioral dimensions of water conservation among Gen Z tourists. This section delineates the practical applications of our findings across multiple operational domains.

The study’s revelation of ECs as a significant predictor of conservation behavior necessitates a reconceptualization of destination management strategies. Tourism managers should implement technologically integrated monitoring systems that provide real-time feedback on water consumption patterns, thereby leveraging Gen Zs digital nativity while reinforcing conservation behaviors. This approach aligns with recent tourism management literature suggesting that data-driven feedback mechanisms can effectively modify tourist behavior [

1]. Furthermore, the development of digital platforms that quantify and visualize water conservation impacts can strengthen the connection between environmental awareness and actual conservation practices.

Our findings regarding the activation of personal norms through situational responsibility suggest the need for structural interventions in tourism facilities. Destination managers should implement standardized water management protocols that explicitly delineate conservation expectations and procedures. These protocols should incorporate both technological solutions (e.g., smart metering systems) and behavioral interventions (e.g., staff training programs) to create a comprehensive conservation framework. The integration of these elements should be guided by empirical evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of multi-modal approaches to behavioral modification in tourism contexts.

The identified mediating role of moral emotions (pride and guilt) in conservation behavior suggests the importance of developing psychologically informed intervention strategies. Tourism organizations should implement recognition systems that reinforce positive conservation behaviors while avoiding punitive approaches that might generate resistance. This recommendation is supported by recent research demonstrating the superior effectiveness of positive reinforcement in sustainable tourism initiatives (Kim & Lee, 2024) [

14]. Additionally, the development of community engagement programs can create emotional connections between tourists and local water conservation efforts, thereby strengthening long-term behavioral commitment.

At the policy level, our findings support the implementation of evidence-based regulatory frameworks that address both supply-side and demand-side aspects of water conservation. Local authorities should establish clear certification standards for water-efficient tourism facilities and develop incentive structures that promote technological innovation in water conservation. These policy instruments should be complemented by monitoring and evaluation systems that enable data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement of conservation initiatives.

The practical implementation of these recommendations requires careful consideration of local contextual factors and stakeholder dynamics. Success metrics should be established to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions across multiple timeframes, enabling adaptive management approaches. This systematic approach to implementing research findings can contribute to the development of sustainable water management practices while enhancing the overall quality of desert tourism experiences.

6.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

While this study advances our understanding of water conservation behaviors among Gen Z tourists in desert destinations, several limitations warrant consideration regarding the generalizability of findings. The study’s geographical focus on Iranian desert villages, while providing valuable insights into a specific cultural context, limits the direct transferability of findings to other cultural settings. The unique characteristics of Iranian desert tourism, including local water management practices and cultural attitudes toward conservation, may differ significantly from other desert destinations globally. While theoretically justified, the study’s exclusive focus on Gen Z tourists constrains our understanding of intergenerational differences in water conservation behaviors. The cross-sectional nature of our data collection further limits our ability to assess temporal changes in conservation behaviors and the long-term stability of the identified relationships between ECs and behavioral outcomes.

These limitations suggest several promising avenues for future research to enhance theoretical understanding and practical applications. Cross-cultural validation studies comparing the model’s effectiveness across different desert tourism destinations would help establish the framework’s broader applicability, while longitudinal investigations could illuminate the stability of ECs and conservation behaviors over time. Future research should also employ mixed-method approaches to provide deeper insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying water conservation behaviors, particularly across different generational cohorts. Furthermore, examining the model’s applicability in other water-sensitive destinations (e.g., island tourism contexts, and coastal regions facing water scarcity) would help establish its robustness across different environmental contexts. Multi-level analyses incorporating both individual and organizational perspectives would provide a more comprehensive understanding of water conservation dynamics in tourism contexts, potentially leading to more effective intervention strategies for sustainable tourism management.