Abstract

For a considerable amount of time, vernacular practices in the Kara Region have resisted external influences. However, they are now confronted with profound changes that are forcing local populations to alter their lifestyle. This study evaluates the sustainability of vernacular buildings and analyzes the causes and consequences of changes in such architecture in the Kara Region. In this context, it focuses on the Kabiyè and Nawdeba peoples, who are the major ethnic groups in the Region. Through a qualitative approach essentially based on the exploration of the existing literature, focus groups with populations, interviews with professionals and a series of surveys on 125 households in the settlements visited, this study highlights the difficulties of people in preserving their architectural identity in favor of imported architectural models. It also reveals that the evolution of vernacular construction practices, although it is a response to certain needs of the population, generates environmental and sociocultural problems. Thus, sustainable architecture in this region requires an update of vernacular practices to better adapt to the needs of local populations.

1. Introduction

The African continent, according to the projections of international institutions, is the continent where the future of humanity is at stake [1,2]. The African population, estimated at 1.308 billion in 2019, will increase by 90% by 2050 (i.e., 2.5 billion people), according to the average assumption of United Nations projections [3]. This population growth is accompanied by strong urbanization, especially in the West African area [4]. United Nations data in West Africa show an average urbanization rate of 45.6% in 2018, with a rate of increase of between 3.5 and 4.8% during the 2020 decade [5]. Apart from high urbanization, the strong population growth in West Africa has also led to the uncontrolled expansion of the main cities, the development of secondary cities and the formation of new rural agglomerations [6]. As a result, the consequences of West African urbanization are noticeable, not only in large cities but also in the intermediate strata (small agglomerations) that statistics struggle to illustrate [7]. Human history has never planned for the energy and infrastructure needs necessary to accommodate such a high population. Estimates suggest that by 2050, we would need to build about 160 million additional units (i.e., about 20,000 housing units per day, and this would be if existing housing is rehabilitated or adapted to new needs) [8]. In Africa, construction (residential and commercial) accounts for 80% of energy expenditure (excluding firewood and biomass) as well as greenhouse gas emissions [9]. Building sustainable cities and human settlements, to be consistent with line 11 of the Sustainable Development Goals [10] which the United Nations adopted in 2015, will not be possible in Africa if the newly constructed buildings consume the same amount of energy as the existing ones. Galloping demography is not the only challenge facing the African continent. Climate change issues are also major challenges. Data from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) indicates that in 2022, climate hazards affected over 110 million people on the continent, resulting in estimated economic damage exceeding $8.5 billion. Despite accounting for only about 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, the continent bears the highest cost in terms of property damage [11].

In Togo, the forecasts of demographic change confirm the rapid growth of the Togolese population. The 5th General Population and Housing Census (RGPH-5) of November 2022 estimates the Togolese population at 8.09 million inhabitants [12]. Based on the average demographic outlook assumption of the National Institute of Statistics and Economic and Demographic Studies (INSEED), Togo’s population will be about 16.5 million by 2053, which is double its current population [13]. This increase, as is the case in the whole West African subregion, coincides with an ever-increasing rate of urbanization. According to INSEED data, the urbanization rate has increased from 37.7% in 2010 to 42.9% in 2022 and is expected to reach 50% within 4 years (in 2026), according to the same source [13]. In addition to the strong urbanization trend, the RGPH-5 also documented an increase in the population of secondary cities. Thus, cities like Kara have almost doubled their population. The population of Kara, estimated at 94,900 in 2010, reached 158,090 in 2022 [12]. This increase in population is also accompanied by a strong demand for infrastructure and energy. Based on data from the National Development Plan (NDP 2018–2022), the deficit in terms of decent housing amounts to 500,000 units in horizon 2020 for the whole of Togolese territory [14]. A study funded by the African Development Fund revealed in November 2022 that each year additional needs of 15,000 units are added to this deficit [15]. The consequences of climate change are also significant in Togo and are manifested in major hazards such as floods, vegetation fires, strong winds, storms, coastal erosion, epidemics, and landslides [16]. The results of the RGPH-5 of November 2022 reveal that housing in Togo is dominated by the “traditional” type (745,221 or 42%), followed by the semi-modern type (541,190 or 31%) and the modern type (481,976 or 27%) [12]. Most of these constructions are vulnerable to climatic hazards. In 2010, for example, the floods caused by the heavy rains that affected the entire territory resulted in the following damage: 35,578 houses were flooded, 3832 damaged and 1330 destroyed [17].

The challenges of the population explosion and climate change in recent years have forced African decision-makers to rethink the construction of African cities by prioritizing respect for and protection of the environment. To improve the sustainability of new constructions, vernacular forms of architecture receive special attention. The International Committee of Vernacular Architecture (CIAV) defines vernacular architecture as architecture of popular inspiration that develops its own characteristics in a specific region, using local materials, construction techniques and traditional forms of that region [18]. Vernacular constructions allowed Man to maintain balance with nature rather than dominate it. They provide an impressive array of innovative strategies that demonstrate the effects of resource-efficient methods on materials and energy consumption. It should be noted that vernacular architecture takes precedence over traditional architecture. The traditional refers to the temporal axis, while the vernacular would refer to the geographical area and a specific social group. The term vernacular architecture is therefore more holistic and encompasses the characteristics of traditional architecture. Vernacular constructions represent much more than mere shelters. They embody the culture of a people, reflecting their values and aspirations through a distinctive architectural language. Vernacular architecture can therefore be an important source of knowledge and inspiration for architects [19]. It is present in both rural and urban areas, encompassing individual buildings, architectural ensembles, as well as urban or rural landscapes. The famous African architect Hassan Fathy was one of the pioneers in highlighting vernacular architecture. Since 1937, Hassan Fathy [20] has initiated earthen projects based on ancient Egyptian techniques. Hassan Fathy’s work convincingly demonstrates that ancient African societies possess a unique architectural heritage. In the West African context, only a few research groups study and document vernacular solutions. Among the exceptions, the CRAterre group and the association La Voûte nubienne deserve a special mention. Donfack Yves [21], Basile Request [22], Madina Yasmine Adjibade [23], Maria Aguilar-Sanchez [24], María Lidón de Miguel [25], Barbara Widera [26], Sébastien Moriset [27], Basile Cloquet [28] and Mathilde Chamodot [28] are among the few authors who make scientific productions on ancestral architectural knowledge in the West African context. Pritzker Prize-winning architect Diébédo Francis Kéré is also a leading figure in this regard and continues to reinvent African architecture by designing innovative projects that adapt perfectly to the local climate.

Referring to the literature review conducted, few scientific studies focused on the production of data on vernacular architecture in Togo. Yet, many examples of remarkable vernacular architecture exist in the country, especially in the Kara Region where our study took place. Apart from the tamberma castles located in the Betammariba area [29], a real scientific covetousness in the Kara Region, the other typologies and traditional construction techniques that also constitute an important heritage are, in our opinion, little studied and not sufficiently documented. The architect Akouete Atsou Fiéfonou, one of the few architects to work on the theme, has proven through this research that traditional architecture in Togo is a bioclimatic architecture. This architecture, which was widely practiced during the pre-colonial and colonial periods (1900 to 1960), almost disappeared during the post-colonial period (1960 to 2021) [30]. For the architect Akouete Atsou Fiéfonou, colonization is the cause of the abandonment of local materials in construction practices. To date, traditional construction practices are losing momentum, especially in the Kara Region. Vernacular architecture in this region, which for a long time resisted external influences, is now confronted with architectural, social and economic changes. Under these conditions, we can only note the gradual disappearance of traditional practices to make way for construction practices made of imported materials, which often prove to be very energy-consuming. In addition, there is the phenomenon of globalization, or international style, that encourages economic, cultural and architectural homogenization through the use of materials such as concrete, steel and glass, thus radically breaking with the traditions of the past. This trend represents a real threat to the sustainability of the traditions of different cultures. As a result, vernacular practices across the world are particularly vulnerable, as they have serious problems with obsolescence, internal balance, and integration [18].

The aim of this article is to understand the causes and consequences of the changes in vernacular architecture in the Kara Region. It seeks to identify the difficulties of local populations in preserving their architectural identity as opposed to imported architectural models. It also wants to analyze the elements of sustainability of vernacular architecture in the Kara Region with the main objective of guiding the actors in the field of construction to the production of architecture adapted to the needs of the population. To achieve the objectives, this work is organized in three phases. First, an analysis of climatic factors is carried out in order to grasp the natural environmental context of the region. Next, we list and examine the various categories of vernacular housing in the Kara Region, both traditional and contemporary. More specifically, formal aspects, construction systems and lifestyles are analyzed. Subsequently, the causes and consequences of the changes from vernacular architecture into the contemporary type of architecture in the Kara Region are presented. A sustainability assessment will then be carried out based on the VerSus (Vernacular and Sustainable) tool [31] in order to determine the orientations that will be beneficial for the design of local architecture that meets the needs of local populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study AREA

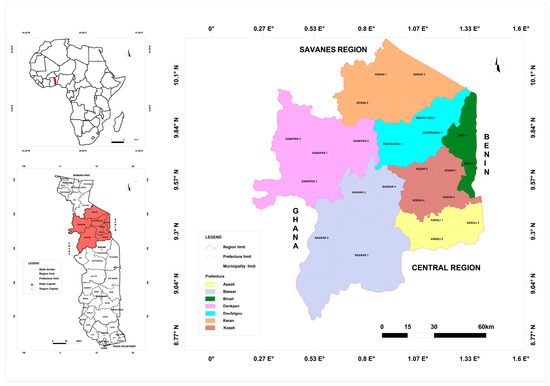

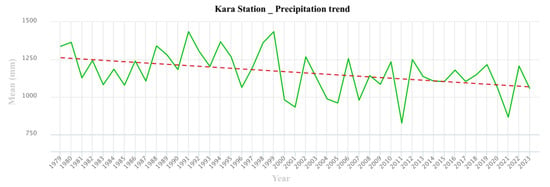

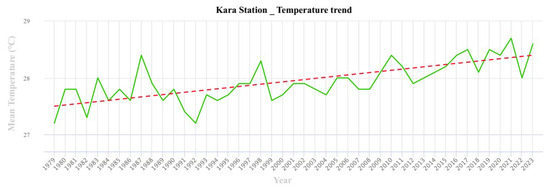

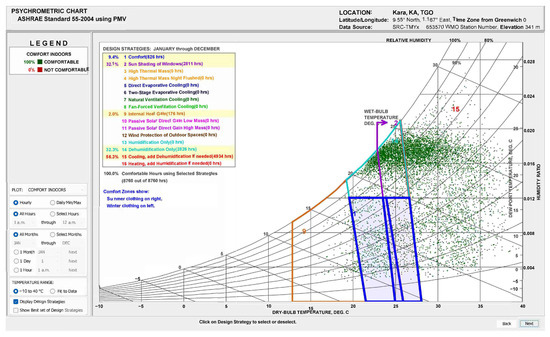

Located in the northern part of Togo, the Kara Region is one of the five regions of the country (Figure 1). According to the WGS84 global ellipsoid, the Kara Region is located between 9’25 and 10’10 north latitude, and between 0’15 and 1’30 east longitude. It covers a total area of 11,490 km2, which represents about 20.50% of the national territory. The Kara Region is bordered to the south by the Central Region, to the north by the Savannah Region, and to the west and east, it borders the Republics of Ghana and Benin, respectively. The Kara Region has a humid tropical climate of the Sudano–Guinean type, with a dry season from November to March and a rainy season the rest of the year. The region records an average rainfall of between 1000 and 1500 mm per year (Figure 2), with little local variations. Monthly average temperatures in the Kara Region range from 25 °C to 31 °C (Figure 3). The data obtained from The National Meteorological Agency of Togo (ANAMET), over the period of 1990–2023, reflect a clear increase in the average temperature from 27 °C in the decade 1990–1999 to 28 °C during the time period of 2000–2023. As far as precipitation is concerned, there is a general downward trend across the region, with variations in the reduction ranging from 15 mm to 98 mm of rainfall. Despite this decrease, the Kara Region has been prone, in recent years, to very excessive rainfall concentrated in short periods, causing flooding throughout the territory. According to data provided by the National Civil Protection Agency (ANPC), in 2021, the Kara Region, precisely, suffered heavy torrential rains, resulting in considerable material damage, injuries and loss of life. The psychrometric diagram (Figure 4) from Climate Consultant version 6.0 presents the useful design strategies for maximum comfort in the Kara Region.

Figure 1.

Map of the Kara Region.

Figure 2.

Precipitation trend in Kara Region. Source: National Meteorological Agency of Togo (ANAMET).

Figure 3.

Temperature trend in Kara Region. Source: National Meteorological Agency of Togo (ANAMET).

Figure 4.

Psychrometric graph of the Kara Region plotted through Climate Consultant. Source: Climate Consultant version 6.0.

The region is subdivided into seven prefectures, namely the prefectures of Kozah, Assoli, Bassar, Binah, Dankpen, Doufelgou and Kéran. In keeping with its diverse cultural heritage, the region has several ethnic groups. These include the Kabiyè, Logba (offshoot of the Kabyé group), Lamba, Tamberma, Sombas, Nawdéba, Kotokoli/Tém, Konkomba people and the Bassar people. All these groups have developed architectures that are rich in their structures and varied forms, perfectly harmonizing with the local environment. According to the 5th RGPH, traditional housing accounts for about 60% of the housing in the Kara Region [12]. Due to the multitude of ethnic groups and cultures that coexist in this region, an analysis of each of the forms of architecture is not practical, as many habitats from different ethnic groups have similar characteristics. However, the region remains dominated by the Kabiyè ethnic group (50.39%, including the Lamba people who represent a sub-group of the Kabiyè people) and the Nawdéba (11.03%) [32]. We will therefore focus our study on the most representative housing models of these two ethnic groups, which together represent more than half of the population of the Kara Region.

2.2. Data Sampling and Processing

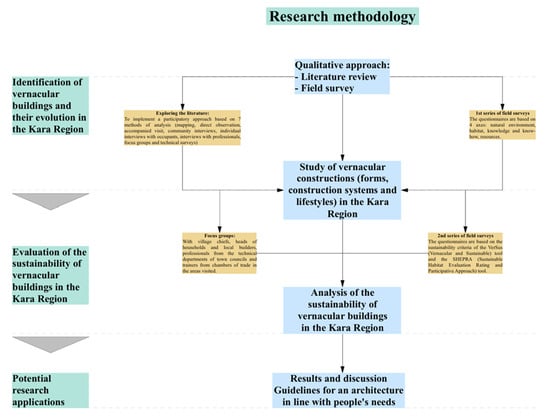

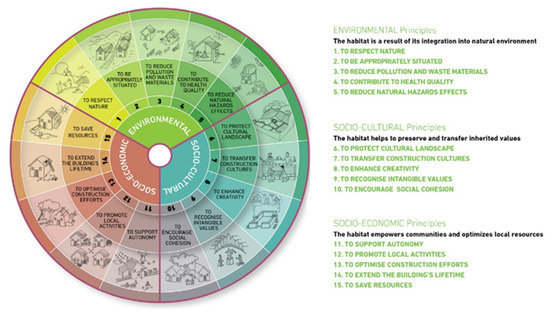

We adopted a qualitative approach for this study, primarily based on literature review and field surveys. The method used is summarized in the Figure 5. The exploration of existing literature through books, articles and government publications has made it possible to review similar works on vernacular buildings. First, the work of Annalisa Caimi [33] and that of Mathilde Chamodot and Basile Cloquet [28] has enabled us to set up a participatory approach to the study of vernacular buildings. This approach is based on 7 methods of analysis, namely mapping, direct observation, guided tours, community interviews, individual interviews with occupants, interviews with professionals, focus groups and technical surveys. The questionnaire used analyzes vernacular buildings according to 4 axes, namely: natural environment, habitat, knowledge and know-how, and resources. We cleaned up and synthesized the collected information from the villages into a table (Table 1 and Table 2). In a second phase, in order to assess the sustainability of the vernacular buildings, a series of surveys was conducted among the target populations through focus groups including village chiefs, heads of households and local builders of the villages visited. The data collected was then consolidated thanks to interviews organized with professionals, in particular the technical departments of the town halls and the trainers of the chambers of trades of the territories visited. We developed the questionnaire for this survey series based on the sustainability indicators of the VerSus (Vernacular and Sustainable) tool (Figure 6) [31]. Indeed, in the field of sustainable construction, various standards and certifications, such as the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) in the United States, the Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) in the United Kingdom, or the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Nachhaltiges Bauen (DGNB) in Germany, etc., make it possible to determine the sustainability of buildings. However, the works of Licia Felicioni [34] show that the majority of these tools do not take into account the three dimensions of sustainability, namely environmental, social and economic, the same way. Environmental impacts receive more attention than social and economic impacts. Since 2014, a methodological tool that comprehensively summarizes the environmental, socio-cultural and socio-economic aspects of architecture has been the 15-indicators wheel developed within the framework of the VerSus project. The VerSus project divides these 15 indicators into groups of 5, one for each aspect of sustainability.

Figure 5.

Research methodology structure.

Table 1.

Inventory of Vernacular Building Practices in the Kara Region.

Table 2.

Synthesis of construction systems in the Kara Region.

Figure 6.

Map showing the indicators of the VerSus tool. Source: https://www.esg.pt/versus/pdf/versus_booklet.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2024).

We have consolidated these indicators for this study, primarily using economic criteria from SEPRA (Sustainable Habitat Evaluation Rating and Participative Approach) tool [35]. These criteria relate to the affordability of construction, which we have included in indicators 13 and 15 of the VerSus tool. We will assign a value to these criteria based on the survey results, allowing us to compare the evolution of architectural forms. Based on the SEPRA tool, a point scale from 0 to 3 will quantify the qualitative responses to the criteria. A score of zero signifies the absence of any aspect of the criteria, indicating a non-existent performance. A score of 1 signifies the meeting of at least one-third of the criteria’s aspects, resulting in a lower performance or underperformance. A score of 2 signifies the fulfilment of two-thirds of the criteria’s elements, meaning a satisfactory performance. A score of 3 signifies an excellent performance, as it meets most aspects of the criteria. Although there is an element of subjectivity, each score awarded is the result of reasoning that is based on observable facts on the ground. This forces the respondents to unanimously justify their answers, thereby reducing the risk of error stemming from the subjectivity component. In the surveys, we apply a sampling method by choice. Reasoned inquiry was applied with the goal of investigating the people most likely to provide accurate information. The prefectures of Kozah, Binah and Doufelgou, being the lands of the Kabiyè and Nawdéba peoples (the major ethnic groups in the region), were surveyed. These prefectures contain a population of about 452,749 inhabitants. Considering that a household contains an average of 5 people according to the 5e RGPH, these territories include about 90,550 households. To determine the sample size, we used Slovin’s formula [36], n = N/(1 + N.e2), where n is the sample size needed, N (90,550) is the population size, and e (4%) is the acceptable margin of error. Thus, we surveyed a total of 125 individuals. Table 3 summarizes the number of respondents broken down by territory.

Table 3.

Sampling of the study area.

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Vernacular Architecture in the Kara Region

3.1.1. Kabiyè Vernacular Architecture (KVA)

- Description

Kabiyè people are the main ethnic group of the Kara Region [37]. They mostly live in the mountains of the same name and their foothills (the prefecture of Kozah and that of Binah). Their origin, according to oral tradition, converges on the idea that these people came down from heaven, even if the location of the first apparition differs from one village to another [32]. Other authors attribute the origin of the Kabiyè to the kingdom of Sudan, which they left because of wars to find better living conditions. For the purpose of managing agricultural land, the Kabiyè scatter their vernacular housing, with an average distance of 50 to 100 m between each dwelling in a neighborhood [38]. The buildings are barely visible in the landscape, but they remain identifiable due to the trees planted nearby for shade. For safety reasons, this habitat developed on the peaks and sides of valleys [39]. It is difficult to see a village-type agglomeration in Kabiyè country. They value a certain independence of families, and the heads of families do not admit any central power that could weaken their ascendancy and be a source of external interference [38]. The Kabiyè habitat plays three main roles. In addition to serving as a dwelling for both the living and the spirits, it also houses animal shelters and stores crops [39]. Round huts, detached from each other and forming an almost circular unit, make up the Kabiyè vernacular settlement. The conical straw roof, overflowing over the entire perimeter, protects the mud walls from deterioration during the rainy season. A wall at human height groups the huts together and serves as a fence, allowing only the vestibule hut as the sole exit to the outside world. To enter the enclosure, one must therefore pass through the two narrow, diametrically opposed doors of the vestibule. Uninvited or unwanted strangers who force their way through are directly strangled inside the compound.

- Way of living

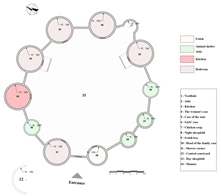

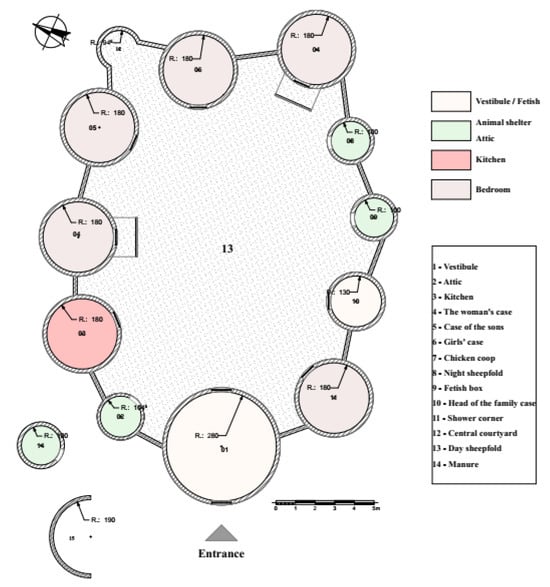

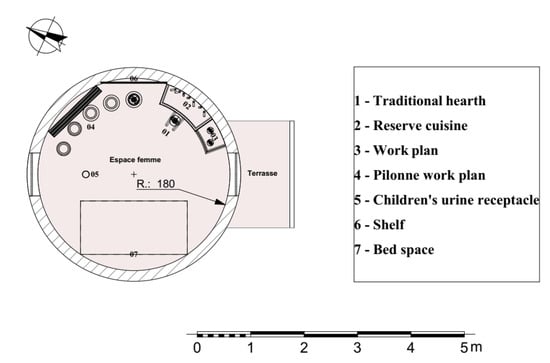

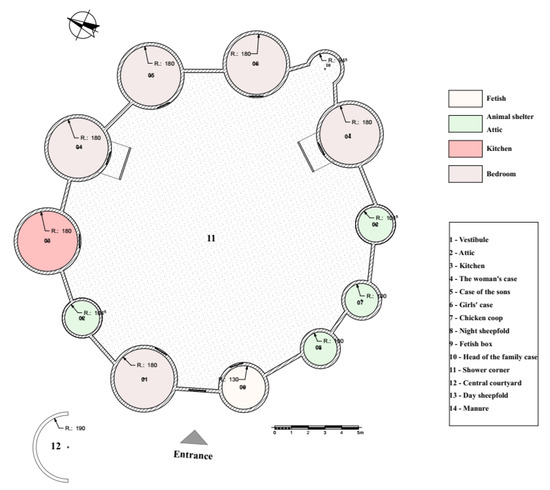

The vernacular habitat in Kabiyè country, because of its isolated position, is designed to ensure its own defense, so its fortified aspect and the management of space are optimized for the state of siege [38]. It generally consists of a vestibule, the father’s room, the mother’s room, the children’s dormitory, the attics and the enclosures used as shelters for the animals, all organized around a central courtyard (Figure 7 and Figure 8). Access to the house is through the vestibule, which is generally the largest hut in each concession, given the important functions it performs. Indeed, the vestibule, in addition to being the place where guests are welcomed, is also the place where millstones, hoes, hunting weapons or trophies, removable chick shelters and other oratorical tools are stored. The vestibule is also the place where customary chiefs discuss and settle their conflicts. They provide earthen seats for this purpose. Within a concession, the huts open onto a central courtyard, which serves both as a gathering place and a drying area. All the crops are stored in solid granaries, and the floor of the well-packed central courtyard is a drying area for agricultural products. Women have their own rooms. Most often, a low terrace separates this room from the outside, where activities occur during the day [39]. The children sleep with their mother until they get their own dorm. Although several huts are traditionally dedicated to them in some concessions, men do not have rooms [38]. When they stop working during the day, they rest either in the vestibule or near it, often on polished stone blocks and under the shade of a large tree. At night, they prefer to rest with their wives. Generally, they set aside the spaces under the attics for poultry. The goats and sheep take refuge in the evening in the vestibule. The ancestors also found their home in the Kabiyè vernacular habitat. In the oldest concessions, a hut was exclusively reserved for fetishes and ancestor worship. Each space serves a purpose, every corner is arranged (chicken coop, nesting box, water reserves) to optimize the management of the space. The sanitary areas consist solely of a shower and urinal. They are built between two huts and a few openings at the bottom of the fence walls are used to drain wastewater to the manure pits. Traditionally, stool is passed out in nature, outside the concessions, in corners set up for this purpose. As the young children stay with their mothers, it can be observed in the women’s hut that the ground is made with a slight slope of 2 to 3% oriented towards a small hole in the center of the hut, which contains ashes (Figure 9 and Figure 10). This device collects children’s urine during the night. Very early in the morning, women maintain this hole to avoid odors. Oil lanterns provide lighting in the absence of electricity. Water is supplied from the many natural water reserves in the region, generally perennial and shared by different families [39].

Figure 7.

Model plan of a concession in Kabiyè territory.

Figure 8.

3D view of a concession in Kabiyè territory.

Figure 9.

Typical plan of the layout of the woman’s hut.

Figure 10.

3D view of the inside of the woman’s hut.

- Materials and construction system

The materials used by the Kabiye people to build their habitat are all available in their immediate environment. Generally built in the dry season, the vernacular housing in Kabiyè country is a result of community work involving men, women and children. The soil obtained by digging the earth is sorted, mixed with water and then kneaded with the feet until it is ready for construction. They leave this earth, which contains a satisfactory quantity of clay, to rest for a few days before alternating it with rows of stones often recovered near the construction site to create the foundation. This foundation is usually 30 cm wide and 20 to 30 cm deep. The above-ground height of the foundation varies depending on the relief and can reach up to 40 cm. They then mark a pause for a maximum of one week to allow the foundation to dry out and fortify before they start erecting the walls. They then erect the walls without formwork, employing a construction technique known as “bauge” [27]. The 20 × 30 cm clods of earth follow one after the other and after each three layers, a pause is observed to allow the wall to solidify. To accommodate the future roof, they prepare holes at a height of 2 m to serve as supports for the wooden framework. They erect windows in the form of small round or triangular holes at a height of one and a half meters in the earthen walls. These windows allow the evacuation of hot air. On some constructions, these types of windows are almost absent. However, all the huts have an oval-shaped opening that serves as an access door. Constructed from plant material (mats made of palm veins tied together by strands of raffia or bark), these doors lead to the central courtyard. Traditionally, carefully selected wood material forms the roof structure. These are often the trunks of the ronier tree, locally called “cocker”, thinning wood stalks, and hard or soft bamboo stalks (raffia). Plant straw thatch serves as the roof material. The most commonly used standard varieties are Kessi and Kingbala. Usually, they cut this straw during the dry season. After drying it for a minimum of two weeks, they braid it into bundles ranging from 4 to 5 m in length. Young palm veins and raffia or sisal fibers, also used to attach the thatch to the framework, form the braid. This conical roof carries a clay pot that joins the top of the straw together. There is also a high quality of finishing, as the walls and floors are carefully packed and coated with successive layer treatments made with the pod of the fruit of the néré tree and a solution based on cow or ox dung to improve the waterproofing of the walls. Decorative elements, made of pottery shards or cowrie shells, are sometimes used to adorn the front of dwelling huts, especially the women’s hut and the vestibule [39]. Note that the construction of granaries often necessitates a mixture of straw and clay (derived from termite mounds). This mixture, once dried, displays good compactness. The attic’s body takes the shape of a cup, narrow in the middle over a man-passage-only opening. Often, a flat stone and a removable straw lid close this opening. The construction of a Kabiyè vernacular dwelling takes an average of 3 to 4 weeks.

3.1.2. Nawdéba Vernacular Architecture (NVA)

- Description

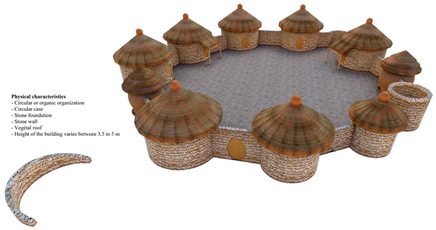

Neighbors to the Kabiyè, the Nawdéba represent, in terms of population, the second most populous ethnic group in the Kara Region. The Nawdéba live mainly in the prefecture of Doufelgou. This prefecture of plains, hills and mountains is dominated by the Défalé mountains, which are covered with white rocks, origin of the name of the prefecture. “White rocks” actually means “Doufelgou” in the Nawdéba language. Like the Kabiyè people, understanding the origin of the Nawdéba remains challenging due to a multitude of myths that vary from village to village. According to the existing literature, the founding couple descended from the sky into a forest. The man was armed and carried tools while the woman had seeds. From this couple were born four sons whose descendants today form the Nawdéba people [40]. Other authors, based on dialects, attribute the origin of the Nawdéba to the Mossis and the Gourma in the north. The vernacular architecture of the Nawdéba is an exceptional cultural curiosity in the Kara Region. In addition to having developed a vernacular architecture in earth like their Kabiyè neighbors, the Nawdéba have developed over the years a vernacular architecture made only of stone. Their land is also the only place in the entire region where this type of construction can be observed. The Nawdéba, like the Kabiyè, have a scattered vernacular habitat. A fence wall connects several round huts, arranged in a more or less circular manner. The walls of the huts are exclusively made of stone, covered by a conical straw roof with a peripheral overhang to protect the walls during the rainy season.

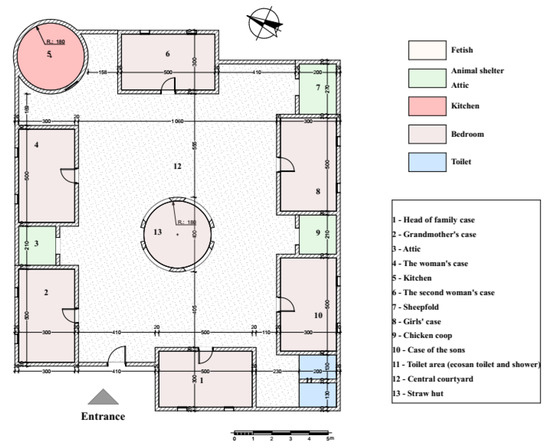

- Way of living

Because of the stone material used, the vernacular habitat in Nawdéba country has a fortified appearance (Figure 11 and Figure 12). The organization of this housing meets the functional and social needs of its inhabitants. It consists of two parts. The first, called the HAGA, represents the family living area and the second, the WAGU, is a crop drying area that also serves as a gathering space (family reunions, handicrafts) [40]. Here, the vestibule is nonexistent, access to the concession is through a main entrance that often opens onto the central courtyard, facilitating access and circulation between the different huts. In this habitat, the layout of the huts reflects the social and family structure of the Nawdéba. The different huts within a concession are occupied by members of the same extended family, with division often based on social status, age and gender. The head of the family and his wives have their own hut. The children stay with their mother until they grow up enough so they can join their dormitory. Women have their own kitchen in an enclosed space, but they usually prefer to cook outside in the central WAGU courtyard. Large and raised granaries are used to store crops and have space for poultry underneath. Goats and sheep benefit from an enclosed space, often in the open air, where they take refuge in the evening. Fetishes and ancestor cults exclusively occupy one space, thus the connection between the habitat and traditional beliefs. The toilet area (shower and urinal) is located in the spaces between two pens and water outlets created at the bottom of the fence walls to evacuate wastewater to the manure pits. Spaces are set up outside the concessions to receive faeces. The habitat lacks both lighting and water supply. Oil lanterns provide night lighting and water is extracted from natural water reserves or wells shared by different families.

Figure 11.

Model plan of a concession in Nawdéba territory.

Figure 12.

3D view of a concession in Nawdéba territory.

- Materials and construction system

In an area strongly dominated by mountains, the vernacular habitat of the Nawdeba is a remarkable example of architecture in harmony with its environment and adapted to the local climatic conditions. To build their habitat, the Nawdéba people mainly use stones. They extract these stones from the white mountains, which are rich in quartzites and micaceous schists [40]. Stone gives the structures an excellent integration into the landscape. Some settlements are built with lateritic stones mixed with sand and rare clay, all of which are the result of the decomposition of rocks. Like the Kabiyè, the entire community (men, women, and children) participates in the building process during the dry season. After the selection and preparation of the land, the Nawdeba first build the foundation of their habitat by digging trenches 30 cm wide to a depth of 20 to 30 cm which they fill by alternating rows of rock stones and clay earth carefully prepared for this purpose. Depending on the relief, the above-ground height of the foundation can be around 60 cm. After a week-long pause, a 40 cm thick wall composed entirely of stone (micaceous schists or lateritic stone) gradually rises without the need for formwork. However, the arrangement and alignment of the stones are meticulously planned to ensure good stability. One of the local craftsmen informed us that daily practices, particularly the arrangement of plant fibers in hat making, often inspire the rhythm of the layout. Craftsmen prepare holes at a height of 2 m to serve as supports for the wooden framework and accommodate the future roof. Windows, sometimes nonexistent on some constructions, are generally very small (small circular holes directly under the roof) to reduce heat entry and maximize shade inside. These windows also serve the purpose of evacuating hot air. The doors made of plant material (bamboo or woven straw) all give access to the central courtyard. The roof framework is made of palm tree trunks locally called “cocker “. This framework supports a thatched roof made of vegetable straw. The dried straw, carefully woven into bundles of 4 to 5 m length, using raffia or sisal fibers and young palm ribs, is fixed to the framework by means of raffia fiber ropes. They attach a clay pot (jar) to the top of the straw to complete the work. Women often finish the floor and walls to a high standard. They later carefully groom the soil and apply successive layers made with the pod of the fruit of the néré tree and a solution based on cow or ox dung to improve the waterproofing of the walls. For the construction of the granaries, a mixture of straw and clay (from the termite mounds) is used, as in Kabiyè architecture, in order to have good compactness. Because of the rigor imposed by the stone material, the construction of a vernacular dwelling in Nawdéba country takes one month.

3.2. The Causes and Consequences of the Evolution from Vernacular Earth or Stone Architecture to Contemporary Architecture

3.2.1. The Causes of the Evolution of Vernacular Architecture

The evolution of vernacular architecture in the Kara Region is characterized by a profound change. This mutation, instead of preserving the vernacular constructive diversity (forms, materials), tends rather towards a significant architectural standardization, which is a real threat to the local built heritage. In this context, the new constructions termed “contemporary architecture” in the context of this research, in both rural and urban areas, no longer exploit vernacular construction values which are therefore abandoned in favor of imported construction techniques. The few traditional habitats that still exist are forsaken or simply in ruins due to a lack of care or maintenance. In the light of the survey and the group discussions organized in the field, the mutation of vernacular architecture can be analyzed according to the following factors:

- Socio-economic factors

The act of building used to be community work. With successive economic crises and the difficulties of earning money, we are witnessing a disappearance of social solidarity in favor of individualism. In addition, the phenomenon of rural exodus, marked by the departure of young adults to the city, leads to a decrease in free family labor. In the absence of this workforce and due to a lack of financial means, many habitats are abandoned and left in ruins due to lack of upkeep and maintenance. For new constructions, owners are forced to recruit workers whose knowledge of vernacular techniques have diminished over the years. It should also be noted that the endorsement of certain value judgments makes it difficult to promote vernacular architecture. In both rural and urban contexts, local materials are perceived as “poor” materials and local construction techniques are considered obsolete and “outdated”. The younger generation is showing a desire to break with the aesthetic and cultural norms of vernacular housing. Anyone who uses it in his concession suffers insults from his community and is often accused of being “stingy or miserly”. Nowadays, more and more people are opting for contemporary homes made of imported materials, as soon as they can afford it. These contemporary homes are often considered a shining symbol of a family member’s financial success. It should also be mentioned that the phenomenon of galloping demography leads to a strong demand in terms of housing construction; a strong demand that vernacular architecture is struggling to meet. Knowing that vernacular constructions take time and are only carried out in the dry season, owners easily opt for contemporary constructions that have the advantage of being carried out at any time of the year. The construction is thus delegated to an external team, which allows the owner to no longer wait for his non-occupation period before devoting himself to his site. Vernacular architecture shows a slow adaptation of the built environment to the new needs of a community characterized by rapid urbanization.

- Historical factor and external influences

In Africa, it is well established that colonization had an impact, profoundly shaping the continent’s cultures [20]. Colonization also impacted traditional architecture, causing a rapid abandonment of ancestral practices in favor of imported architecture. People widely perceive the settler as a catalyst for progress, leading to the adoption of his methods and achievements. Unlike the southern part of Togo, colonization took time to take hold in the north of the country [41]. Vernacular architecture in the Kara Region has therefore resisted external influences for a long time before finding itself today confronted with profound changes. For the architect Akouete Atsou Fiéfonou, traditional architecture in Togo is a bioclimatic architecture strongly practiced during the pre-colonial and colonial periods (1900 to 1960). It almost disappeared during the post-colonial period (1960 to 2021). Colonization is therefore indexed as one of the reasons for the abandonment of local construction values [30]. In addition to this colonization factor, there is the phenomenon of globalization, which advocates economic, cultural and architectural uniformity. Globalization is a real threat to the survival of people’s traditions. Thus, vernacular practices and structures around the world are extremely vulnerable because they face serious problems of obsolescence, internal equilibrium and integration [18].

- Ecological factors

In the Kara Region, the scarcity of construction materials is a growing concern. According to the testimony of local manufacturers and referring to the National Strategy for the Reduction of Emissions due to Deforestation and Forest Degradation [42], this rarity can be explained by the phenomenon of transhumance, which is on the rise in the region. Every year, huge herds roam the region freely, ignoring the planned transhumance routes, and even venturing into protected forest areas. They sow chaos by causing overgrazing, wiping out crops, ravaging forests and plant species used in construction. On the other hand, we are witnessing in the Kara Region the phenomenon of deforestation, which is a consequence of the high population in the region. This high population leads to enormous needs for energy and agricultural production. Agricultural expansion is therefore the leading cause of deforestation in the Kara Region. It includes slash-and-burn agriculture; the burning of which is often uncontrolled, leading to the disappearance each year of dozens of hectares of forests, wooded land and thus plant species used in construction. Today, we observe that this type of agriculture employs fertilizers that denature the soil by reducing its clayey texture. The local people interviewed indicated that this earth produces balls or bricks that are less resistant to erosion and more sensitive to it. The second cause of deforestation is the abusive exploitation of forest resources for energy purposes. Indeed, wood energy in the form of charcoal is used by more than 80% of the rural population, and the sector is mainly supplied by intensive and informal harvesting activities [42]. Most of the wood that could be used for construction is used to supply kitchens of rural households and also in urban areas where the population is very dependent on biomass to meet its energy needs (especially charcoal).

- Political factors

Local authorities in the Kara Region or the central government clearly do not draw inspiration from vernacular construction values for most of the projects they develop and carry out, whether in rural or urban areas. Rural infrastructure projects such as schools, health centers, markets and public administrations are conceived as an imported architectural model that struggles to integrate into its immediate environment. An exception should be noted for the PAD project (to support decentralization), financed by German cooperation, which offered mayors built in BTCS (cement-stabilized earth bricks) [43]. At the national level, the central government has virtually no policy in place to promote local materials. The only institution working on this subject is the CCL (Center for Construction and Housing), which is a semi-public body created in the aftermath of independence with an administrative character under the supervision of the Ministry of Urban Planning, Housing and Land Reform. The main mission of the CCL is to improve housing in Togo by conducting research on available local materials. Despite its training and awareness-raising efforts, this organization struggles to promote local materials.

3.2.2. The Consequences of the Evolution of Vernacular Architecture

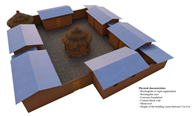

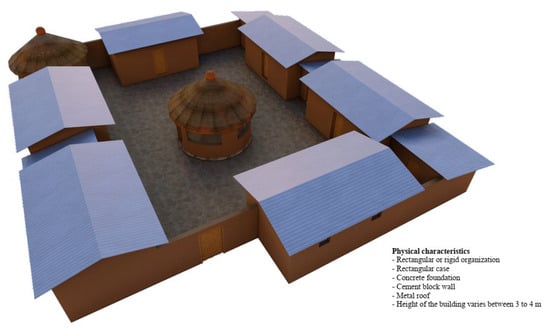

All these factors have resulted in profound changes in the vernacular architecture of the Kara Region (Figure 13 and Figure 14). In recent years, there has been a simplification of the organization of vernacular architecture in Kabiyè country and in the Nawdéba land as well. Rectangular or square-shaped rooms have replaced the round-shaped huts that once dominated the architectural landscape. According to the residents interviewed, several factors explain this choice.

Figure 13.

Model plan of contemporary architecture in Kara Region.

Figure 14.

3D Model of contemporary architecture in Kara Region.

Indeed, on a Kabiyè or Nawdeba vernacular habitat, the most common interventions concern straw roofs that require replacement every two years. Faced with this demanding constraint, homeowners more easily opt for the use of metal roofing such as corrugated iron, which is more resistant during the rainy season. These materials are also more accessible than straw, which has become scarcer due to deforestation [42]. Despite their higher cost, corrugated sheets are becoming increasingly popular, driving demand and promoting their supply and availability from suppliers. Rectangular rooms are a popular choice because their shape aligns with the position of the human body on the bed. The owners assert that this shape provides more interior space for conversion compared to round huts, even without the need for additional columns.

In addition to corrugated iron, imported industrial materials are increasingly predominant. The natural wood frame with its imperfections is replaced by a metal or timber frame. Tar and oil replace waterproof solutions based on néré or shea butter in the manufacture of coatings. Natural wood doors and windows are gradually being replaced by sheet metal or steel. Concrete and cement blocks are used for the construction of foundations and walls instead of earth and stones. According to the work of Tossim, cement is used up to 81% in the construction of walls [44]. Nowadays, the «bauge» technique used in the past is no longer relevant. The rectangular huts are built with mud bricks (10 to 15 cm) for the less well-off or with cement bricks of the same thickness for the “rich”. Only buildings of secondary importance, such as kitchens, stables and granaries, retain their traditional configuration (form and materials). The kitchens have kept their position outside the bedrooms. This is also the case for toilets, which now have ECOSAN or VIP (Ventilated Improved Pit) type toilets. Sanitary facilities are located outdoors to safeguard the earthen walls from potential moisture buildup. The decision to protect kitchens from potential fires caused by smoke or sparks explains this choice. The vestibule hut, an important element of Kabiyè vernacular architecture, almost no longer exists in new constructions. Despite the settlements retaining their vast courtyards for harvest drying, the circular layout of the huts has undergone dislocation. There is also a noticeable slackness, illustrated by the generally neglected quality of the finishes of new houses. The decorations on the facades of the women’s huts have completely vanished. According to the owners interviewed, the objective of all these changes is to increase the resistance of buildings to extreme weather conditions and to reduce the frequency of construction maintenance work. However, this new trend is not without its drawbacks. The main disadvantage of these new constructions lies in their obvious thermal and noise discomfort. The owners of this type of residence testify to their discomfort, especially during periods of high heat when the temperature inside can exceed that of the outside. This is because cement lacks the beneficial characteristics of clay, particularly when it comes to thermal control. These circumstances pose particular challenges in rural areas where the lack of mechanical ventilation systems complicates the situation. Houses built of earth and covered with cement plaster or tar also have disadvantages in terms of comfort, as these coatings alter the natural characteristics of the earth and hinder the permeability of the walls. Steel, the primary material for roofs and other metal elements like doors and windows, absorbs solar energy and disperses heat both indoors and outdoors. The rectangular hut has exposed facades, unlike the round hut, which has none. These exposed facades increase the heat input inside the rooms, which accentuates thermal discomfort. In addition to their thermal discomfort, the residents interviewed confirm the acoustic discomfort of these metal roofs during heavy rainfall.

3.3. Assessing the Sustainability of Vernacular Architecture in the Kara Region

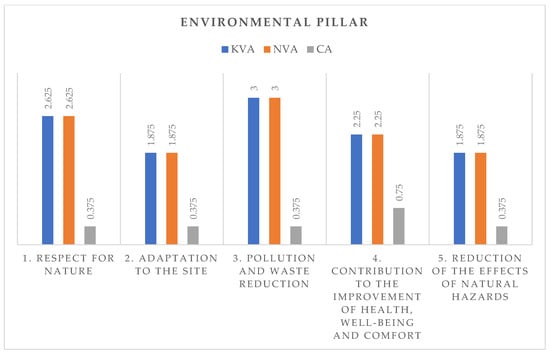

We analyzed the vernacular architecture in Kabiyè and Nawdéba countries and their evolution using the sustainability criteria of the VerSus project [31]. The tables and figures below (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 and Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18) show the degree of performance of each type of architecture from an environmental, socio-economic and socio-cultural point of view.

Table 4.

Evaluation of vernacular architecture in the Kara Region according to the VerSus tool.

Table 5.

Assessment according to environmental criteria.

Table 6.

Evaluation according to socio-cultural criteria.

Table 7.

Evaluation according to socio-economic criteria.

Figure 15.

Assessment according to environmental criteria.

Figure 16.

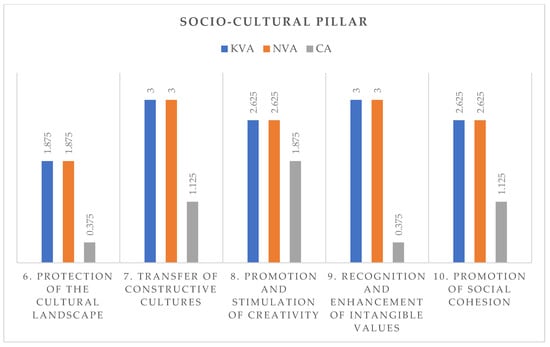

Evaluation according to socio-cultural criteria.

Figure 17.

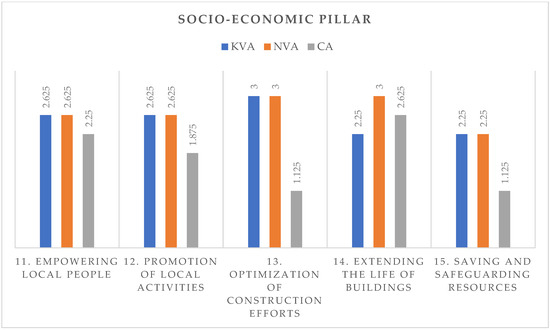

Evaluation according to socio-economic criteria.

Figure 18.

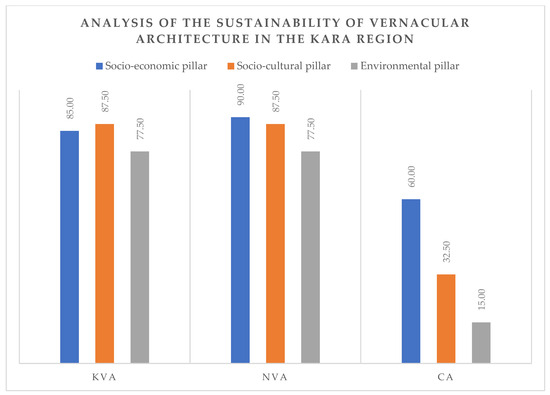

Evaluation according to socio-economic, socio-cultural and environmental criteria.

- Environmental pillar

The environmental indicators of the VerSus tool (indicators 1, 2, 3 and 5) show a value of 0.375 for contemporary architecture, which reflects an underperformance of the CA. Indicator 4 (0.75), for the CA, points out some provisions to improve comfort, which are insufficient for a good performance of the CA. Indicators 1 and 3 for vernacular architecture in Kabiyè and Nawdéba countries have a value of 2625 and 3, respectively, which reflects an excellent performance for the KVA and the NVA Indicators 2, 4 and 5 for VKA and AVN show a value of 1875, 2.25 and 1875, respectively, reflecting a good performance of KVA and NVA.

- Socio-cultural pillar

The socio-cultural indicators of the VerSus tool (indicators 6, 7, 9 and 10) show a value of 0.375, 1.125, 0.375 and 1.125, respectively, for contemporary architecture, which reflects an underperformance of the CA. Indicator 8 indicates a value of 1.875 for CA, reflecting its good performance. Indicators 7, 8, 9 and 10, for Vernacular Architecture in Kabiyè and Nawdéba Country, have a value of 3, 2625, 3 and 2625, respectively, which reflects an excellent performance of the KVA and the NVA. This is not the case for indicator 6 (1875 for the KVA and the NVA), which reflects good performance.

- Socio-economic pillar

Indicator 14 of the VerSus tool shows a value of 2.625 for contemporary architecture CA, which indicates an excellent performance of the CA. This is not the case for indicators 13 and 15, which show a value of 1.125 for CA, and thus reflecting underperformance. Indicators 11 and 12 show the values of 2.25 and 1.875, respectively, for the CA, thus reflecting a good performance. Indicators 11, 12 and 13 for Vernacular Architecture in Kabiyè and Nawdéba countries have a value of 2625, 2625 and 3, respectively, which reflects an excellent performance for the KVA and the NVA. Indicator 14 shows a value of 2.25 for KVA and 3 for NVA. This reflects an excellent performance for the NVA and a good performance for the KVA. This is also the case for indicator 15, which shows a value of 2.25 for the NVA and the KVA.

4. Discussions

4.1. Environmental Pillar

According to Figure 18, CA integrates up to 15% of all the environmental criteria of the VerSus project. This proves that CA generates environmental problems, unlike KVA and NVA, which both obtain 77.50%. KVA and NVA blend easily into their immediate surroundings due to their organic shape and natural materials, CA stands out strongly for its rigidity and right angles. While it is true that the use of metal (for the roof or doors and windows) makes it possible to limit the consumption of wood, the production of this material, although locally available, requires heavy energy-intensive machinery. This is also the case for cement, a locally available material, but the production of which remains a threat to the environment. Nowadays, cement production accounts for 5–8% of global carbon dioxide emissions [45]. In many cases, the manufacture of waterproof coatings using tar and oil instead of néré or shea juice relies on archaic extraction techniques, which not only pollute the environment but also harm the health of workers. The use of all these materials creates large temperature variations [46], which are a source of thermal discomfort. This observation is shared by Tossim [44], who, through her work, has demonstrated that houses made of cement do not promote thermal comfort. According to Karyono [47], commonly used metal roofs act as radiation heat transfer surfaces, which helps to warm indoor spaces during sunny periods. Building in accordance with international concrete standards and incorporating technical provisions such as the foundation and concrete structure, the CA exhibits superior strength and requires less maintenance than the KVA and NVA. However, KVA and NVA are renowned for their ability to improve over time. The ruins of the earthen and stone constructions we visited during our field investigation reveal walls and foundations that remain resilient. It is worth mentioning here that the vulnerability of CA to the effects of increasingly intense climatic hazards in the region is a striking element. This observation is confirmed by the Regional Multi-Hazard Contingency Plan of the Kara Region [48], which defines metal roofing, most often constructed with a low slope, as a vulnerability element. The CA is susceptible to roof dislodging during periods of heavy rain or strong winds. According to respondents, even today, the KVA or NVA remains a safe and peaceful place during climatic phenomena. Heavy rainfall is often the cause of the acoustic discomfort observed with the CA. The KVA and NVA do not value ventilation or daylighting. Indeed, traditional constructions often lack windows. Also, it should be mentioned that the presence of ecosan toilets in the CA improves the sanitation of the living environment, unlike the KVA and the NVA where the sanitary space is limited to a shower or a urinal. Despite the lack of a toilet area, ventilation and adequate lighting, the VKA and AVN are still more environmentally efficient than the AC.

4.2. Socio-Economic Pillar

According to Figure 18, the CA, the NVA and the KVA integrate 60%, 90% and 85%, respectively, of all the socio-economic criteria of the VerSus project. This reflects the local availability of most of the materials used, whether for CA, KVA or NVA. Apart from the naturally available stone and earth, cement that was once imported is now produced locally thanks to Cimtogo, which has a production unit in the region with a capacity of 250,000 tons per year. This observation is shared by Armelle Choplin [49], from whom we note that the availability of cement is promoted by the public authorities and donors who consider the fact of pouring cement as a means of development or better of emergence. This is also demonstrated by A. Mawussi [50], who explains that governments, producers, and donors frequently support the cement industry, making it more influential. These latter, with the aim of reducing the cost of cement and making it more accessible to a wider audience, are increasing production. Additionally, Togo’s technical high schools widely disseminate the cement technique, reflecting the availability of manpower. The exploitation of this workforce actively contributes to the promotion of the local economy and reduces the need for self-construction and community work. However, the use of this material and the labor involved are expensive compared to KVA and NVA. Therefore, owners often choose to construct their homes informally, using a low-skilled workforce that does not adhere to any reinforced concrete construction standards. Compared to the KVA and the NVA, which undergo regular maintenance after each rainy season, the CA requires less frequent maintenance. However, maintenance or repair work on the CA sometimes involves heavy financial burdens, especially when the construction is of poor quality. In addition, despite the proven resistance of the CA, the options for modification remain limited. Adjustments require significant investments, especially about demolition, which requires additional effort and the use of appropriate tools due to the permanent nature of cement, reinforced concrete or metal materials.

4.3. Socio-Cultural Pillar

According to Figure 18, only 32.5% of the socio-cultural criteria of the VerSus project are met by contemporary architecture. This proves that the CA generates socio-cultural problems, unlike the KVA and the NVA which both obtain 87.50%. The CA reflects a real desire to exhibit success. This observation is shared by Armelle Choplin [49], from whom we note the desire to build with cement in Africa is a way to display social success, even if cement constructions are not adapted to the tropical climate and require enormous energy consumption for air conditioning. In both rural and urban contexts, the elements of the KVA and the NVA are perceived as obsolete, “outdated” and their criteria of beauty are no longer unanimous. This is also the view of M. Lovizit [51], for whom local materials are generally seen as a symbol of precariousness. As a result, CA does not really show any concern for cultural identity, unlike the KVA or the NVA, which value the cultural landscape. The creation of contemporary housing in a family context aims to assert personal or family members’ wealth. As a result, the CA lacks a historical reference point to contribute to collective memory. It should also be noted that the KVA and the NVA have difficulty resolving the housing deficit due to the phenomenon of galloping demography because their implementation requires a relatively long time compared to the CA. Owners opt for contemporary architecture due to their ability to be realized year-round with a workforce of varying qualifications. This is not the case for the KVA or the NVA, which is community work and a ground for learning and knowledge transmission. The CA is therefore in line with the needs of the social groups in that respect.

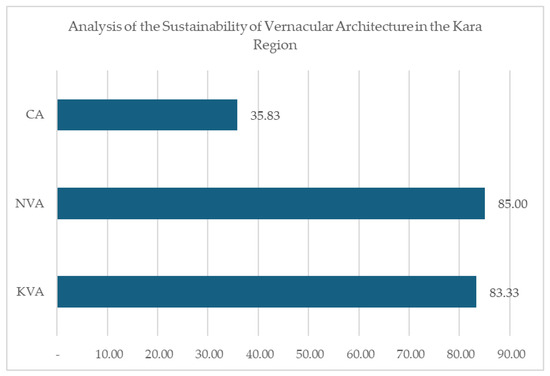

The evaluation according to all the criteria of the VerSus tool assigns an average sustainability score of 35.83% to contemporary architecture. The vernacular architecture of Nawdéba and the vernacular architecture of Kabiyè obtain average scores of 85% and 83.33%, respectively (Figure 19). The analysis of the sustainability of vernacular buildings in the Kara Region shows that the CA has shortcomings, especially in the environmental and sociocultural aspects. This result supports the work of Madina Yasmine Adjibade [23], who demonstrated that contemporary buildings do not meet sustainability criteria, even though they address certain needs of the population. Unlike AC, AVK and AVN offer better durability and value the know-how and practices of traditional construction. This observation is also shared by Donfack, Yves [21], who, through his work, recommends a return to vernacular construction practices to formulate sustainable responses to the housing problem in Africa and to offer a better living environment for future generations. However, the AVK and AVN require improvements, particularly in terms of ventilation and natural lighting, which need to be more effective. The sanitation conditions must also be improved in the AVK and AVN. The following table outlines the strengths and weaknesses of vernacular architecture in the Kara Region (Table 8).

Figure 19.

Evaluation of vernacular architecture in the Kara Region according to the VerSus tool.

Table 8.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Vernacular Architecture.

5. Conclusions

This article on the sustainability elements of vernacular architecture in northern Togo reflects the evolution of vernacular architecture typologies in the Kara Region and analyzes its performance in light of the evaluation criteria of the VerSus tool. This study, based on the indicators of the VerSus tool, reveals that vernacular architecture in the Kara Region, whether in Kabiyè or in Nawdéba country, is sustainable architecture. VerSus reveals that vernacular architecture in Nawdéba country boasts a sustainability level of 85%, surpassing the 83.33% achieved by vernacular architecture in Kabiyè country. The evolution of these forms of architecture, although it is a response to certain needs of the populations, is not sustainable. With a sustainability level of 35%, contemporary architecture generates environmental and socio-cultural problems. We believe that vernacular architecture has the necessary resources to be an effective response to the current challenges on the continent. For this, vernacular architecture must be revisited, particularly in terms of sanitation, ventilation, and natural lighting. It must integrate green technologies in order to create more comfortable living environments that adapt to the current needs of social groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y.A. and E.K.A.D.; methodology, M.Y.A., E.K.A.D. and Y.D.; software, M.Y.A. and E.K.A.D.; formal analysis, Y.D. and P.V.G.; investigation, M.Y.A., D.K.G. and E.K.A.D.; resources, M.Y.A. and D.K.G.; data curation, M.Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.A.; writing—review and editing, M.Y.A., Y.D. and E.K.A.D.; visualization, M.Y.A. and E.K.A.D.; supervision, Y.D. and P.V.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the World Bank through the Regional Center of Excellence on Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON), funding number IDA 5360 TG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the World Bank and the University of Lomé (UL) via the Regional Center of Excellence for Sustainable Cities in Africa (CERViDA-DOUNEDON) for their financial contributions and scientific supervision.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mangeon, A.; Lopes, C. L’Afrique est L’Avenir du Monde. Repenser le Developpement; Lectures; Cyril Le Roy: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, J. Peuplement, migrations, urbanisation: Où va la population mondiale? Popul. Avenir 2016, 728, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nations Unies Perspectives de La Population Mondiale—Division de La Population. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Beaujeu, R.; Kolie, M.; Sempere, J.F.; Uhder, C. Transition Démographique et Emploi en Afrique Subsaharienne; Agence Française de Développement (AFD): Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 2105-553 X.

- Les Villes Africaines Face à La Crise de La Mobilité Urbaine: Le Défi Des Politiques Nationales de Mobilité Au Bénin, Au Burkina Faso, Au Mali et Au Togo Face à La Prolifération Des Deux-Roues Motorisés|SSATP. Available online: https://www.ssatp.org/publication/african-cities-facing-urban-mobility-crisis-challenge-national-mobility-policies-benin (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Giraut, F.; Moriconi-Ebrard, F. La Densification Du Semis de Petites Villes En Afrique de l’Ouest. Mappemonde 1991, 24, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapport Régional de la Conférence des Nations Unies sur le Logement et le Développement Urbain Durable (Habitat III) pour l’Afrique: Innovations en Matière de Logement et de Développement Urbain Durable en Afrique. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/k16/097/74/pdf/k1609774.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Observatoire de L’action Climat en Afrique Note de Diagnostic Habitat Durable et Changement Climatique en Afrique. Available online: https://www.climate-chance.org/comprendre-observatoire/blog-observatoire-mondial/note-de-diagnostic-habitat-durable-et-resilient-en-afrique/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Joffroy, T.; Misse, A.; Celaire, R.; Rakotomalala, L. Architecture Bioclimatique et Efficacité Énergétique Des Bâtiments Au Sénégal; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2017; hal-02025559, Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bodiguel, J. Objectif 11: Faire en Sorte que les Villes et les Etablissements Humains Soient Ouverts a Tous, sûrs, Résilients et Durables. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/fr/cities/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- ONU L’Afrique Pâtit du Changement Climatique de Manière Disproportionnée. Available online: https://news.un.org/fr/story/2023/09/1138192 (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- L’institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques et Demographiques (INSEED) Résultats Finaux du 5e Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitat (RGPH-5) de Novembre 2022. Available online: https://inseed.tg/depliant-et-communique-rgph/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- L’institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques et Demographiques (INSEED) Perspectives Demographiques du Togo 2011–2031. Available online: https://inseed.tg/download/2471/?tmstv=1727340134 (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- République Togolaise Plan National de Devéloppement (PND). Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/Tog184778.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- African Development Bank Assistance Technique pour les Etudes de Faisabilité du Projet de Construction des 20.000 Logements à Cout Abordable—Rapport D’evaluation de Projet. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/fr/documents/togo-assistance-technique-pour-les-etudes-de-faisabilite-du-projet-de-construction-des-20000-logements-cout-abordable-rapport-devaluation-de-projet (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Commission Economique Pour l’Afrique (CEA); Bureau des Nations Unies Pour la Réduction des Risques de Catastrophes (UNISDR) Rapport D’evaluation Sur L’integration et La Mise En Oeuvre Des Mesures de Réduction Des Risques de Catastrophe Au Togo. Available online: https://archive.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/Natural_Resource_Management/drr/drr-in-togo_french_final.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Ministère de L’environnement et des Ressources Forestières Plan d’action National D’adaptation Aux Changements Climatiques (PANA). Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/Tog184779.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Charte Du Patrimoine Bâti Vernaculaire—International Council on Monuments and Sites. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/fr/participer/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/178-charte-du-patrimoine-bati-vernaculaire (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Oliver, P. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; ISBN 978-0-521-56422-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, H. Construire Avec Le Peuple Histoire d’un Village d’Egypte: Gourna; ACTES SUD: Paris, France, 1996; ISBN 978-2-7427-0807-9. [Google Scholar]

- Donfack, K.; Aurelien, Y. Evolution de L’habitat Traditionnel en Afrique. Exemple de la Province de L’ouest au Cameroun; Universitätsbibliothek der Technischen Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéré, B. Architecture et Cultures Constructives Du Burkina Faso; UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation: Paris, France, 1995; Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/v9s4qgp (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Adjibadé, M.Y. Mutations Architecturales et Quête de Développement en Milieu Rural Burkinabè: Appuyer L’évolution Pertinente des Cultures Constructives Locales pour la Conception d’un Habitat Catalyseur de Durabilité. Available online: https://archipel.uqam.ca/9225/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Aguilar-Sanchez, M.; Almodovar-Melendo, J.-M.; Cabeza-Lainez, J. Thermal Performance Assessment of Burkina Faso’s Housing Typologies. Buildings 2023, 13, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidón de Miguel, M.; Vegas, F.; Mileto, C.; García-Soriano, L. Return to the Native Earth: Historical Analysis of Foreign Influences on Traditional Architecture in Burkina Faso. Sustainability 2021, 13, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widera, B. Comparative Analysis of User Comfort and Thermal Performance of Six Types of Vernacular Dwellings as the First Step towards Climate Resilient, Sustainable and Bioclimatic Architecture in Western Sub-Saharan Africa. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriset, S. Entretien Des Sikien (Togo, Koutammakou): Cahier de Recommandations; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2022; hal-03550868, Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chamodot, M.C.; Cloquet, B. Modes D’habiter, Cultures Constructives et Habitat De Demain au Pays Dogon; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2008; dumas-03196898, Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Centre du Patrimoine Mondial Koutammakou, le Pays des Batammariba. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/fr/list/1140/ (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Akoueté, A.F. Contribution de L’architecture Bioclimatique au Developpement Durable des Villes du Togo; Generis: Chișinău, Moldova, 2023; ISBN 979-8-88676-776-6. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaud, H.; Moriset, S.; Sànchez Muñoz, N.; Sevillano Gutiérrez, E. Versus: Lessons from Vernacular Heritage to Sustainable Architecture; CRAterre-ENSAG: Villefontaine, France; UNICA, Università Degli Studi di Cagliari: Cagliari, Italy; UNIFI, Università Degli Studi di Firenze: Florence, Italy; UPV, Universidad Politécnica de Valencia: Valence, Spain, 2014; ISBN 978-2-906901-78-0. [Google Scholar]

- Tata, P. Approche Sociologique Des Causes Internes Du Sous-Développement: La Politique de L´«Authenticité Africaine» et Paupérisation—Cas Des Cérémonies Funéraires Traditionnelles Des Kabiyè Au Togo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Trier, Trier, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Caimi, A. Cultures Constructives Vernaculaires et Résilience: Entre Savoir, Pratique et Technique: Appréhender le Vernaculaire en Tant que Génie du Lieu et Génie Parasinistre. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Grenoble, Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Felicioni, L.; Lupíšek, A.; Gaspari, J. Exploring the Common Ground of Sustainability and Resilience in the Building Sector: A Systematic Literature Review and Analysis of Building Rating Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalaina, R.; Génis, L.; Cartier, S.; Garnier, P. Décrypter SHERPA: Un Outil Pour Évaluer La Durabilité Des Projets D’habitats; HAL Open Science: Lyon, France, 2015; hal-01239335, Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zubin, J.; Guilford, J.P. Fundamental Statistics in Psychology and Education. Am. J. Psychol. 1944, 57, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayibor, N.L.; Barbier, J.-C.; Marguerat, Y. Le Peuplement du Togo: Etat Actuel des Connaissances Historiques. Available online: https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/divers19-12/010009851.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Lucien-Brun, B.; Pillet-Schwartz, A.-M. Les Migrations Rurales des Kabyè et des Losso, Togo; IRD Editions: Montpellier, France, 1987; ISBN 978-2-7099-0822-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvaget, C. Boua, Village De Koude, un Terroir Kabye (Togo Septentrional) [Etude D’ une Petite Region: Environnement Physique, Population, Agriculture, Migrations]; ORSTOM: Paris, Ferance, 1981; ISBN 2-7099-0605-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tcham, B. Mythes D’autochtonie et Histoire: Le Cas Des Nawdeba. Rev. CAMES Sci. Soc. Hum. Ser. B 2003, 5, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lippelt, J. Narratives of Collective Memory: The Memory of German Colonization in Togo Today (Erzählungen Des Kollektiven Gedächtnisses: Die Erinnerung an Die Deutsche Kolonialzeit Im Heutigen Togo). Master’s Thesis, Brandenburg University of Technology, Cottbus, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- République Togolaise. Ministère de L’environnement et des Ressources Forestières Stratégie Nationale de Réduction Des Émissions Dues à La Déforestation et à La Dégradation Des Forêts (REDD+). Available online: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/Tog183988.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Republique Togolaise Décentralisation: Des Communes Dotées de Nouvelles Infrastructures Administratives. Available online: https://www.republiquetogolaise.com/gestion-publique/1706-9382-decentralisation-des-communes-dotees-de-nouvelles-infrastructures-administratives (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Tossim, M.J.; Tombar, P.A.; Banakinao, S.; Mavunda, C.A.; Sondou, T.; Aholou, C.C.; Ayité, Y.M.X.D. Analysis of the Choice of Cement in Construction and Its Impact on Comfort in Togo. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, S.H.; Wiedmann, T.; Castel, A.; de Burgh, J. Hybrid Life Cycle Assessment of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Cement, Concrete and Geopolymer Concrete in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 152, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, N.A.M.; Behaz, A.; Denan, Z. Thermal Comfort Studies on Houses in Hot Arid Climates. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 401, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karyono, T.H. Report on Thermal Comfort and Building Energy Studies in Jakarta—Indonesia. Build. Environ. 2000, 35, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANPC TOGO Plan Regional de Contingence Multirisques: Region de la Kara. Available online: https://anpctogo.tg/plans/ (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Choplin, A. Produire la ville en Afrique de l’Ouest: Le corridor urbain de Accra à Lagos. Inf. Géogr. 2019, 83, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawussi, A. Armelle Choplin (2020), La Vie du Ciment en Afrique. Matière Grise de L’urbain; Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer. Revue de Géographie de Bordeaux; MetisPresses: Geneve, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 74, pp. 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozivit, M. Exposition Cotonou(s), Histoire D’une Ville “sans Histoire”; URBACOT: Cotonou, Benin, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).