How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

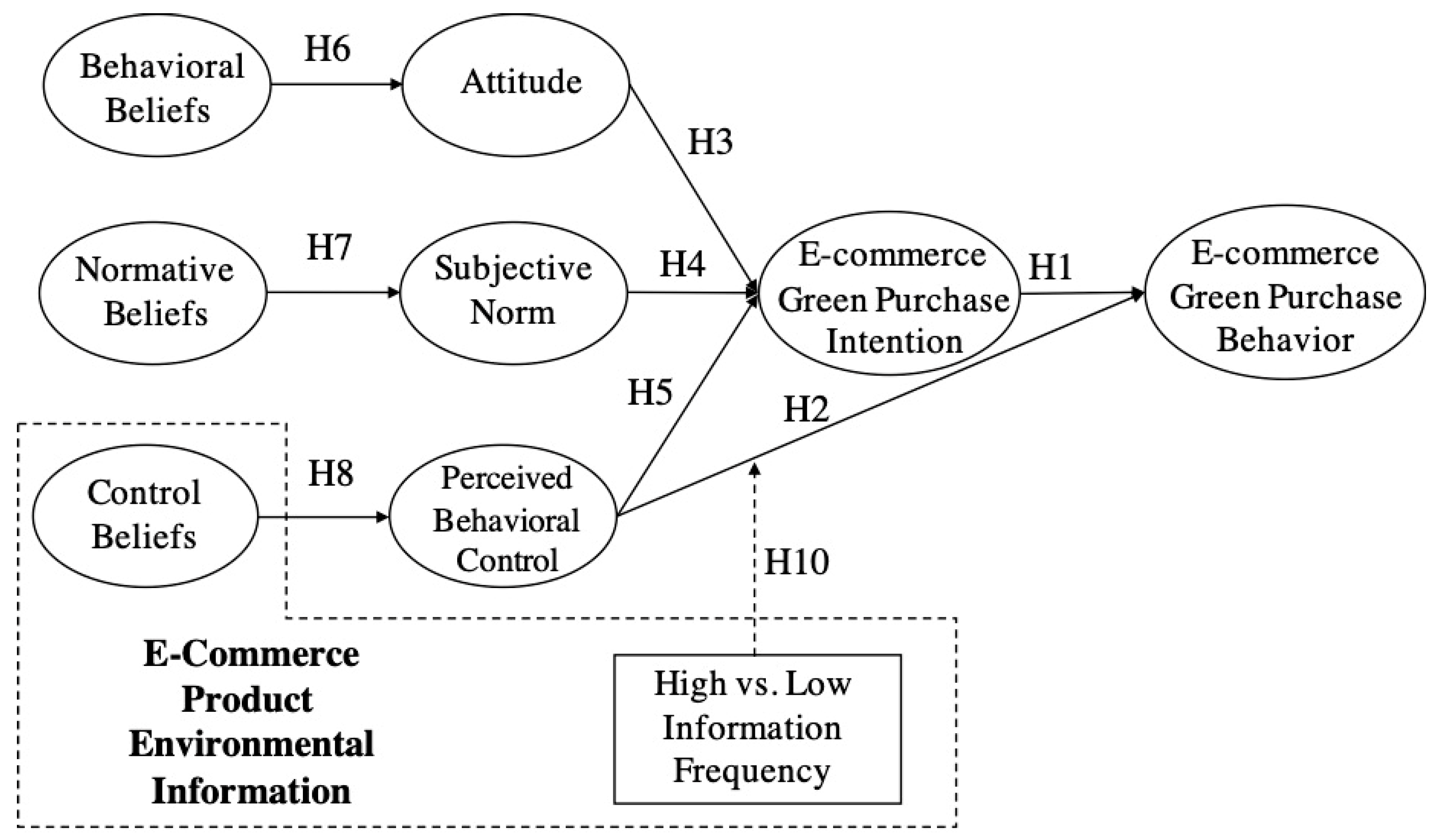

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2. Frequency of Information

2.3. Product Type

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis Methods

4. Results

4.1. Model Reliability and Validity

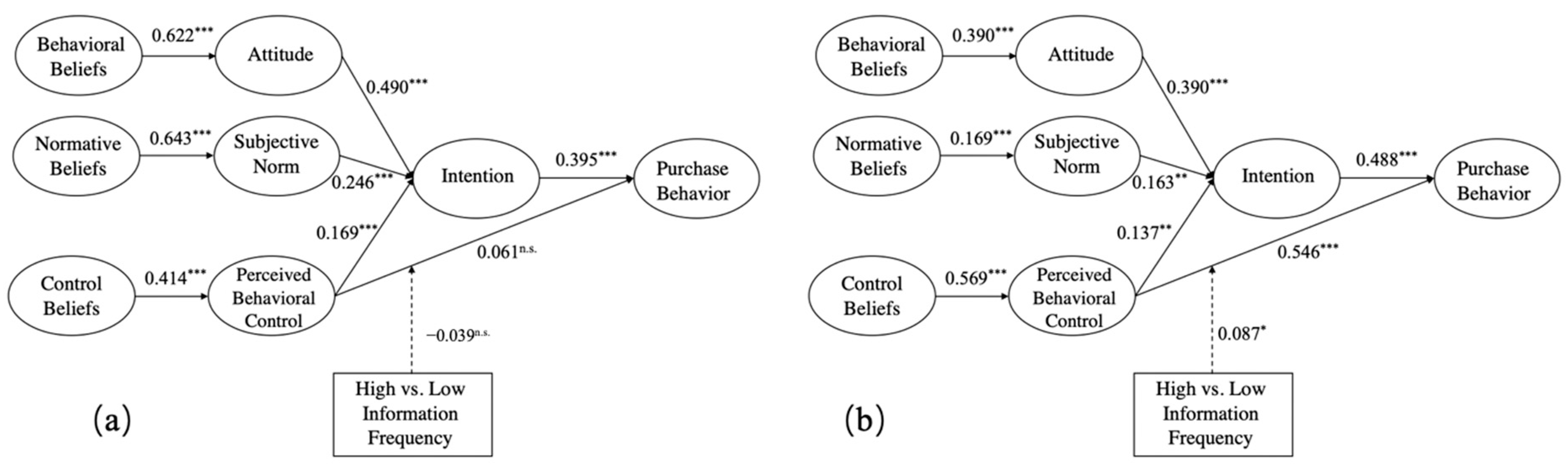

4.2. Structural Results

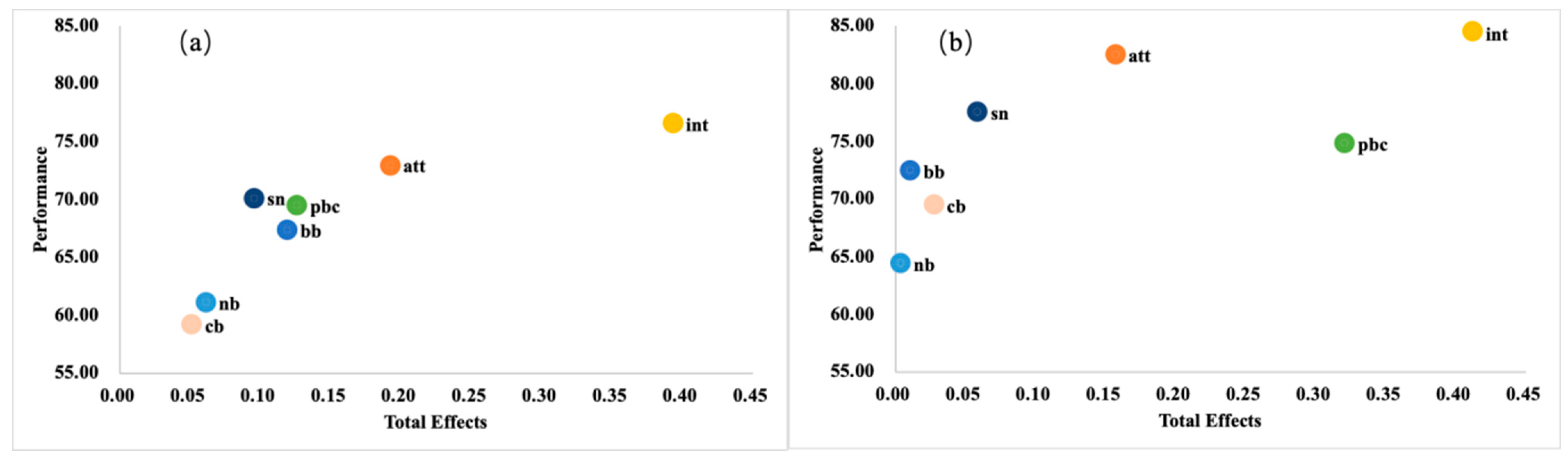

4.3. IPMA Analysis

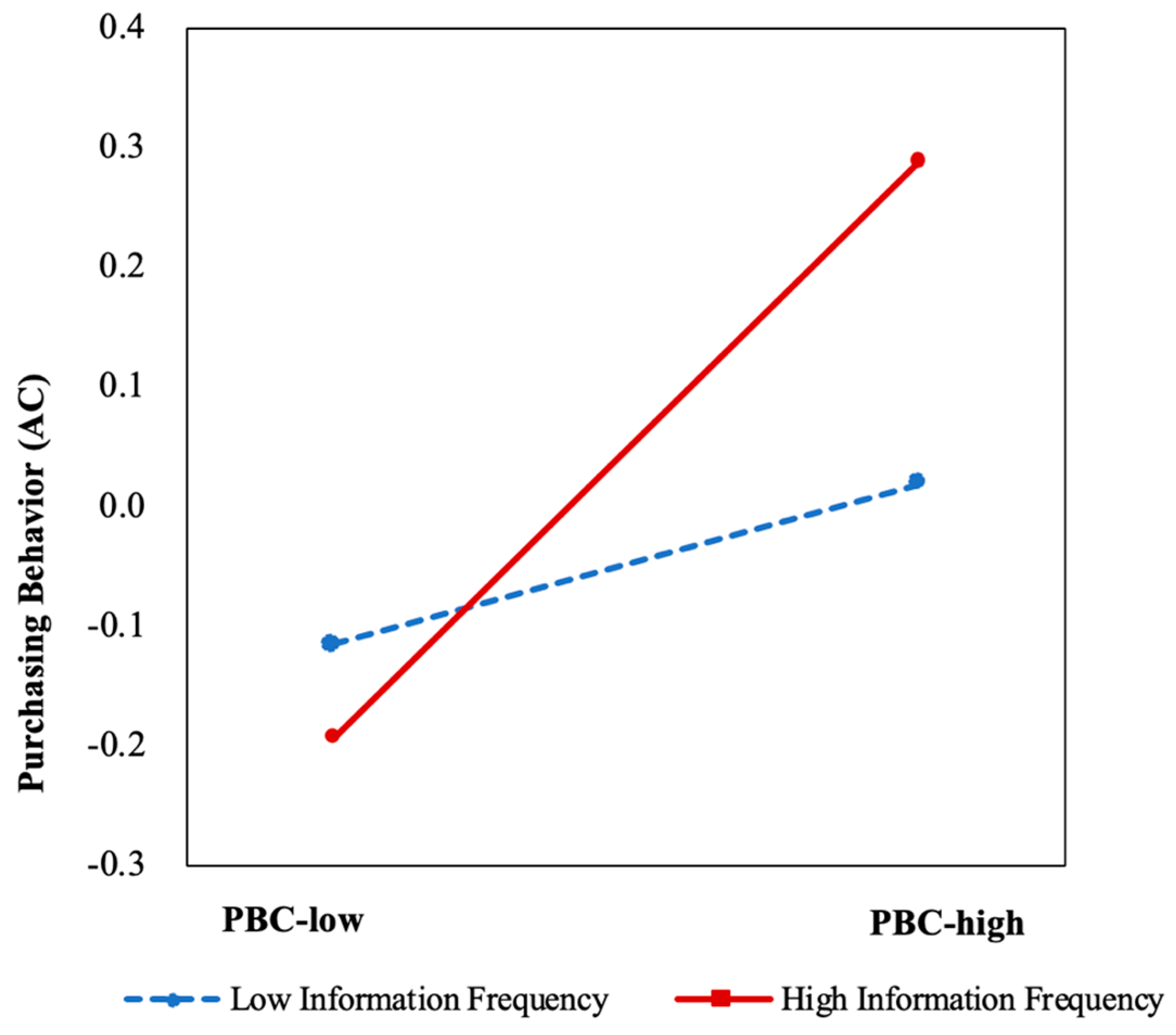

4.4. The Moderating Effect of Information Frequency

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis Based on Consumer Characteristics

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Behavioral Beliefs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted | Beliefs | Outcome evaluation | Outcomes (milk) | Outcomes (AC) |

| bboe1 | bb1 | oe1 | environment protection | environment protection |

| bboe2 | bb2 | oe2 | nutritional value | electricity bill savings |

| bboe3 | bb3 | oe3 | food safety | cooling/heating performance |

| Normative beliefs | ||||

| Weighted | Beliefs | Motivation to comply | Referents (milk) | Referents (AC) |

| nbmc1 | nb1 | mc1 | friends and family | friends and family |

| nbmc2 | nb2 | mc2 | online advertising | online advertising |

| nbmc3 | nb3 | mc3 | online reviews and product ratings | online reviews and product ratings |

| nbmc4 | nb4 | mc4 | brand | brand |

| Control beliefs | ||||

| Weighted | Beliefs | Perceived power | Control factors (milk) | Control factors (AC) |

| cbpp1 | cb1 | pp1 | traceability information | carbon reduction information |

| cbpp2 | cb2 | pp2 | nutrient information such as protein content | energy saving performance |

| cbpp3 | cb3 | pp3 | organic labels | energy efficiency labels |

| cbpp4 | cb4 | pp4 | promotion and sales | promotion and sales |

References

- Peng, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhen, S.; Liu, Y. Does digitalization help green consumption? Empirical test based on the perspective of supply and demand of green products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, A.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Dangelico, R.M.; de Medeiros, J.F.; Marcon, É. Exploring green product attributes and their effect on consumer behaviour: A systematic review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.; Li, A. Intervention policies for promoting green consumption behavior: An interdisciplinary systematic review and future directions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Campos, B.; Qi, X. A literature review on the drivers and barriers of organic food consumption in China. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The Importance of Consumer Trust for the Emergence of a Market for Green Products: The Case of Organic Food. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, M.; Jiang, X. Propensity of green consumption behaviors in representative cities in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.; Ceccarelli, G.; Fraccascia, L. Consumer behavioral intention toward sustainable biscuits: An extension of the theory of planned behavior with product familiarity and perceived value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 5681–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Seok, J.; Kim, Y. Unveiling ways to reach organic purchase: Green perceived value, perceived knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawde, S.; Kamath, R.; ShabbirHusain, R.V. ‘Mind will not mind’—Decoding consumers’ green intention-green purchase behavior gap via moderated mediation effects of implementation intentions and self-efficacy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M. In green consumption, why consumers do not walk their talk: A cross cultural examination from Saudi Arabia and UK. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Aagaard, E.M.N. Elaborating on the attitude-behaviour gap regarding organic products: Young Danish consumers and in-store food choice. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-W.; Chen, Y.-S.; Yeh, Y.-L.; Li, H.-X. Sustainable consumption models for customers: Investigating the significant antecedents of green purchase behavior from the perspective of information asymmetry. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 1668–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. An extended model of value-attitude-behavior to explain Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Nayga, R.M. Green identity labeling, environmental information, and pro-environmental food choices. Food Policy 2022, 106, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Internet Use on Closing Intention-Behavior Gap in Green Consumption-A Mediation and Moderation Theoretical Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Jin, S.; Wu, W. Interactive effects of information and trust on consumer choices of organic food: Evidence from China. Appetite 2024, 192, 107115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, D.; Yang, G.; Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, D. Appliance energy labels and consumer heterogeneity: A latent class approach based on a discrete choice experiment in China. Energy Econ. 2020, 90, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaenzig, J.; Heinzle, S.L.; Wuestenhagen, R. Whatever the customer wants, the customer gets? Exploring the gap between consumer preferences and default electricity products in Germany. Energy Policy 2013, 53, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y. Comparing influencing factors of online and offline fresh food purchasing: Consumption values perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 12995–13015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G. Online or in-store: Unravelling consumer’s channel choice motives. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.; Chakraborty, D.; Siddiqui, A. Consumers buying behaviour towards agri-food products: A mixed-method approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelmann, M.; Schubert, R. How Do Different Designs of Energy Labels Influence Purchases of Household Appliances? A Field Study in Switzerland. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 144, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Li, C. Research on strategies for improving green product consumption sentiment from the perspective of big data. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Alba, J.L.; Abou-Foul, M.; Nazarian, A.; Foroudi, P. Digital platforms: Customer satisfaction, eWOM and the moderating role of perceived technological innovativeness. Inf. Technol. People 2021. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Customer behavior in purchasing energy-saving products: Big data analytics from online reviews of e-commerce. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, M.; Leenheer, J. Energy efficiency of consideration sets and choices: The impact of label format. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 2484–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zheng, J.; Luo, S. Green power of virtual influencer: The role of virtual influencer image, emotional appeal, and product involvement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, L.N.; Tung, L.T. The second-stage moderating role of situational context on the relationships between eWOM and online purchase behaviour. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 42, 2674–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavlanova, T.; Benbunan-Fich, R.; Lang, G. The role of external and internal signals in E-commerce. Decis. Support Syst. 2016, 87, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhou, L. The dual roles of web personalization on consumer decision quality in online shopping: The perspective of information load. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhang, K.; Yang, P.; Jiao, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, C. Information exposure incentivizes consumers to pay a premium for emerging pro-environmental food: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsthoorn, M.; Schleich, J.; Guetlein, M.-C.; Durand, A.; Faure, C. Beyond energy efficiency: Do consumers care about life-cycle properties of household appliances? Energy Policy 2023, 174, 113430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. Effects of personal carbon trading on the decision to adopt battery electric vehicles_ Analysis based on a choice experiment in Jiangsu, China. Appl. Energy 2018, 209, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, L.; Papu Carrone, A.; Jensen, A.F.; Zarazua de Rubens, G.; Kester, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Willingness to pay for electric vehicles and vehicle-to-grid applications: A Nordic choice experiment. Energy Econ. 2019, 78, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión Bósquez, N.G.; Arias-Bolzmann, L.G. Factors influencing green purchasing inconsistency of Ecuadorian millennials. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 2461–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gan, C.; Le Trang Anh, D.; Nguyen, Q.T.T. The decision to buy genetically modified foods in China: What makes the difference? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 15213–15235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Shi, L. Identify and bridge the intention-behavior gap in new energy vehicles consumption: Based on a new measurement method. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehawy, Y.M.; Ali Khan, S.M.F. Consumer readiness for green consumption: The role of green awareness as a moderator of the relationship between green attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Samiei, N. The impact of electronic word of mouth on a tourism destination choice Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Internet Res. 2012, 22, 591–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swidi, A.; Saleh, R.M. How green our future would be? An investigation of the determinants of green purchasing behavior of young citizens in a developing Country. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13436–13468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006; p. 12. Available online: https://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, G. Willingness to pay a price premium for energy-saving appliances: Role of perceived value and energy efficiency labeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, F.; Lichters, M.; Krey, N. The touchy issue of produce: Need for touch in online grocery retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, Z. Live streaming commerce and consumers’ purchase intention: An uncertainty reduction perspective. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, S. Social learning and public policy: Lessons from an energy-conscious village. Energy Policy 2006, 34, 2929–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiefenbeck, V.; Goette, L.; Degen, K.; Tasic, V.; Fleisch, E.; Lalive, R.; Staake, T. Overcoming Salience Bias: How Real-Time Feedback Fosters Resource Conservation. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 1458–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, L.; Gan, X.; Sun, Y.; Lv, T.; Qiao, L.; Xu, T. Effects of monetary and nonmonetary interventions on energy conservation: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 149, 111342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior, 1st ed.; Pearson: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-13-936435-8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, X.; Sun, J.; Jiang, Y.; Qiang, W. How does experience impact the adoption willingness of battery electric vehicles? The role of psychological factors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 25230–25247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, M.; Chu, Y.; He, L. Should “Green” Be Precise? The Effect of Information Presentation on Purchasing Intention of Green Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Li, W. The impact of motivation, intention, and contextual factors on green purchasing behavior: New energy vehicles as an example. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 1249–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solà, M.D.M.; Escapa, M.; Galarraga, I. Effectiveness of monetary information in promoting the purchase of energy-efficient appliances: Evidence from a field experiment in Spain. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 95, 102887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, A.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. Drivers and barriers for purchasing green Fast-Moving Consumer Goods: A study of consumer preferences of glue sticks in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Chart of Economic and Social Development: Basic Information of the Population of Megacities in the Seventh National Population Census. 16 September 2021. Available online: http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2021-09/16/c_1127863567.htm (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Lannes, B.; Deng, D.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J. Three Trends Lead the Future: Upmarket, Small Brands, and New Retail. 2019. Available online: https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/dwl.php?sn=publications&id=1379 (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- MOFCOM. 2022 China E-Commerce Retail Market Development Report. 2023. Available online: https://cif.mofcom.gov.cn/cif/html/upload/20230221113312045_2022%E5%B9%B4%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E7%BD%91%E7%BB%9C%E9%9B%B6%E5%94%AE%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%BA%E5%8F%91%E5%B1%95%E6%8A%A5%E5%91%8A.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y. Consumer’s intention to purchase green furniture: Do health consciousness and environmental awareness matter? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbach, N.; Ahlemann, F. Structural equation modeling in information systems research using Partial Least Squares. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2010, 11, 5–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Li, M.; Hao, Y. Purchasing Behavior of Organic Food among Chinese University Students. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance-performance map analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1865–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender Differences in Environmental Behaviors Among the Chinese Public: Model of Mediation and Moderation. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 975–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-J. Investigating beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding green restaurant patronage: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Jagu, D.; Lu, Y.; Ma, X. Why energy-efficient behaviors are delayed? Exploring the moderating role of procrastination in green ticks experiment probing household refrigerator upgrading. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 101, 107118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, A.C.; Ishida, A.; Matsuda, R. Ethical food consumption drivers in Japan. A S–O-R framework application using PLS-SEM with a MGA assessment based on clustering. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierobisch, T.; Toporowski, W.; Dannewald, T.; Jahn, S. Flagship stores for FMCG national brands: Do they improve brand cognitions and create favorable consumer reactions? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, P.; Zheng, Y. How to obtain customer requirements for each stage of the product life cycle from online reviews: Using mobile phones as an example. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 80, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, H.; Thøgersen, J. Does online chatter matter for consumer behaviour? A priming experiment on organic food. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 850–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Liu, Y.; Wei, X. Influence of online product presentation on consumers’ trust in organic food: A mediated moderation model. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 2724–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Hong, D. Gender differences in environmental behaviors in China. Popul. Environ. 2010, 32, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, M. Factors and mechanisms affecting green consumption in China: A multilevel analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 209, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Su, X. How impacting factors affect Chinese green purchasing behavior based on Fuzzy Cognitive Maps. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to green consumption: A systematic review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Han, C.; Teng, M. The influence of Internet use on pro-environmental behaviors: An integrated theoretical framework. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzinger, A.; Steiner, W.; Tatzgern, M.; Vallaster, C. Comparing low sensory enabling (LSE) and high sensory enabling (HSE) virtual product presentation modes in e-commerce. Inf. Syst. J. 2022, 32, 1034–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.-W.; Chen, S.-C.; Lin, P.-H.; Hsieh, C.-I. Evaluating the user interface and experience of VR in the electronic commerce environment: A hybrid approach. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, G.A.; Lunardi, G.L.; Dolci, D.B. From e-commerce to m-commerce: An analysis of the user’s experience with different access platforms. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 58, 101240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Siponen, M.; Zhang, X.; Lu, F.; Chen, S.; Mao, M. Impacts of platform design on consumer commitment and online review intention: Does use context matter in dual-platform e-commerce? Internet Res. 2022, 32, 1496–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 25 and below | 199 | 18.06% |

| 26~40 | 778 | 70.60% | |

| 41~50 | 98 | 8.89% | |

| 51~60 | 23 | 2.09% | |

| 60 and above | 4 | 0.36% | |

| Gender | Male | 452 | 41.02% |

| Female | 650 | 58.98% | |

| Income (Yuan/month) | 3000 and below | 61 | 5.54% |

| 3001–5000 | 111 | 10.07% | |

| 5001–8000 | 248 | 22.50% | |

| 8001–10,000 | 250 | 22.69% | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 320 | 29.04% | |

| 20,000 and above | 112 | 10.16% | |

| Education | primary school and below | 1 | 0.09% |

| senior high | 14 | 1.27% | |

| high school | 65 | 5.90% | |

| graduate | 919 | 83.39% | |

| postgraduate and above | 103 | 9.35% | |

| Sample Size | 1102 | 100% | |

| Items | Milk | AC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | |

| att1 | 0.823 | 0.766 | 0.865 | 0.681 | 0.787 | 0.662 | 0.816 | 0.597 |

| att2 | 0.828 | 0.741 | ||||||

| att3 | 0.826 | 0.788 | ||||||

| int1 | 0.848 | 0.778 | 0.871 | 0.693 | 0.746 | 0.679 | 0.824 | 0.609 |

| int2 | 0.799 | 0.782 | ||||||

| int3 | 0.849 | 0.812 | ||||||

| pbc1 | 0.831 | 0.765 | 0.864 | 0.680 | 0.859 | 0.740 | 0.853 | 0.659 |

| pbc2 | 0.804 | 0.763 | ||||||

| pbc3 | 0.838 | 0.810 | ||||||

| sn1 | 0.821 | 0.760 | 0.862 | 0.676 | 0.798 | 0.740 | 0.853 | 0.659 |

| sn2 | 0.814 | 0.786 | ||||||

| sn3 | 0.832 | 0.787 | ||||||

| Milk | ATT | INT | PBC | SN | |

| ATT | 0.825 | ||||

| INT | 0.693 | 0.832 | |||

| PBC | 0.307 | 0.399 | 0.825 | ||

| SN | 0.613 | 0.601 | 0.324 | 0.822 | |

| AC | ATT | INT | PBC | SN | |

| ATT | 0.772 | ||||

| INT | 0.547 | 0.780 | |||

| PBC | 0.463 | 0.396 | 0.812 | ||

| SN | 0.445 | 0.402 | 0.286 | 0.790 |

| Formative Construct | Milk | AC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formative Items | VIF | Formative Items | VIF | |

| Behavioral Belief | bboe1 | 1.159 | bboe1 | 1.080 |

| bboe2 | 1.181 | bboe2 | 1.051 | |

| bboe3 | 1.227 | bboe3 | 1.070 | |

| Control Belief | cbpp1 | 1.213 | cbpp1 | 1.072 |

| cbpp2 | 1.180 | cbpp2 | 1.098 | |

| cbpp3 | 1.275 | cbpp3 | 1.147 | |

| cbpp4 | 1.010 | cbpp4 | 1.027 | |

| Normative Belief | nbcm1 | 1.250 | nbcm1 | 1.211 |

| nbcm2 | 1.193 | nbcm2 | 1.308 | |

| nbcm3 | 1.268 | nbcm3 | 1.182 | |

| nbcm4 | 1.291 | nbcm4 | 1.182 | |

| Path | Model 1 (Milk) | Model 2 (AC) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p Value | β | p Value | |

| BB -> ATT | 0.622 | 0.000 *** | 0.390 | 0.000 *** |

| CB -> PBC | 0.414 | 0.000 *** | 0.569 | 0.000 *** |

| NB -> SN | 0.643 | 0.000 *** | 0.169 | 0.000 *** |

| INT -> BH | 0.395 | 0.000 *** | 0.488 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC -> BH | 0.061 | 0.151 n.s. | 0.546 | 0.000 *** |

| ATT -> INT | 0.490 | 0.000 *** | 0.390 | 0.000 *** |

| PBC -> INT | 0.169 | 0.000 *** | 0.137 | 0.002 ** |

| SN -> INT | 0.246 | 0.000 *** | 0.163 | 0.001 ** |

| ATT -> INT -> BH | 0.194 | 0.000 *** | 0.182 | 0.000 *** |

| BB -> ATT -> INT -> BH | 0.120 | 0.000 *** | 0.066 | 0.000 *** |

| BB -> ATT -> INT | 0.305 | 0.000 *** | 0.038 | 0.001 ** |

| CB -> PBC -> BH | 0.025 | 0.163 n.s. | 0.222 | 0.000 *** |

| CB -> PBC -> INT | 0.070 | 0.000 *** | 0.067 | 0.003 ** |

| NB -> SN -> INT | 0.158 | 0.000 *** | 0.080 | 0.001 ** |

| NB -> SN -> INT -> BH | 0.062 | 0.000 *** | 0.099 | 0.000 *** |

| SN -> INT -> BH | 0.097 | 0.000 *** | 0.017 | 0.006 ** |

| PBC -> INT -> BH | 0.067 | 0.000 *** | 0.031 | 0.004 ** |

| CB -> PBC -> INT -> BH | 0.028 | 0.000 *** | 0.027 | 0.008 ** |

| Group | Path | Coefficients | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | Moderating Effect -> BH | −0.031 | 0.379 n.s. |

| AC | Moderating Effect -> BH | 0.087 | 0.039 * |

| Hypotheses | Milk | AC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2 | PBC positively influences e-commerce green purchasing behavior | Not supported | Supported |

| H9 | Product environmental information influences behavior through the mediating effect of PBC | Not supported | Supported |

| H10 | Information frequency moderates the relationship between PBC and behavior | Not supported | Supported |

| Path | Gender (Male vs. Female) | Age (Young vs. Old) | Income (Low vs. High) | Education (Low vs. High) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Significance | p-Value | Significance | p-Value | Significance | p-Value | Significance | |

| ATT -> INT | 0.289 | n.s. | 0.523 | n.s. | 0.196 | n.s. | 0.735 | n.s. |

| BB -> ATT | 0.453 | n.s. | 0.003 | ** | 0.019 | ** | 0.581 | n.s. |

| CB -> PBC | 0.495 | n.s. | 0.373 | n.s. | 0.789 | n.s. | 0.016 | ** |

| INT -> BH | 0.030 | ** | 0.396 | n.s. | 0.004 | ** | 0.086 | n.s. |

| NB -> SN | 0.896 | n.s. | 0.070 | n.s. | 0.635 | n.s. | 0.944 | n.s. |

| PBC -> BH | 0.815 | n.s. | 0.121 | n.s. | 0.134 | n.s. | 0.962 | n.s. |

| PBC -> INT | 0.802 | n.s. | 0.881 | n.s. | 0.860 | n.s. | 0.616 | n.s. |

| SN -> INT | 0.893 | n.s. | 0.781 | n.s. | 0.283 | n.s. | 0.590 | n.s. |

| Path | Education (Low vs. High) | |

|---|---|---|

| p-Value | Significance | |

| ATT -> INT | 0.289 | n.s. |

| BB -> ATT | 0.453 | n.s. |

| CB -> PBC | 0.495 | n.s. |

| INT -> BH | 0.030 | ** |

| NB -> SN | 0.896 | n.s. |

| PBC -> BH | 0.815 | n.s. |

| PBC -> INT | 0.802 | n.s. |

| SN -> INT | 0.893 | n.s. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Peng, M.; Li, Y.; Ren, M.; Ma, T.; Zhao, W.; Xu, J. How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062337

Wang X, Peng M, Li Y, Ren M, Ma T, Zhao W, Xu J. How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062337

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xintian, Meng Peng, Yan Li, Muhua Ren, Tao Ma, Weidong Zhao, and Jiayu Xu. 2025. "How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062337

APA StyleWang, X., Peng, M., Li, Y., Ren, M., Ma, T., Zhao, W., & Xu, J. (2025). How E-Commerce Product Environmental Information Influences Green Consumption: Intention–Behavior Gap Perspective. Sustainability, 17(6), 2337. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062337