Abstract

China has made significant progress in environmental protection. As the country advances towards modernizing its environmental governance, environmental sociology plays an increasingly crucial role. This study employs a bibliometric analysis of 3867 publications from the Web of Science Core Collection (1972–2023) and CNKI (1990–2023) to reveal the disparities between Chinese and international environmental sociology research, with a particular focus on assessing the contributions of environmental sociology to environmental governance in China. The findings reveal several key insights. The results show a steady increase in global research output, with the United States (42.79%) and the United Kingdom (11.15%) leading in publication volume. While international research has expanded interdisciplinary collaboration, Chinese studies remain highly concentrated. The findings also reveal a growing tension between internationalization and localization in Chinese environmental sociology. Since 2017, publications in international journals have surged, while domestic publications have declined, reflecting scholars’ prioritization of global recognition over local policy engagement. However, language barriers and limited interdisciplinary integration—with over 80% of scholars rooted in philosophy and sociology—restrict the discipline’s ability to address complex governance challenges. Institutional influence remains imbalanced. Renmin University, Hohai University, and the Ocean University of China contribute 42.72% of domestic publications, yet no Chinese institution ranks among the global top 10, and citation impact lags behind leading Western institutions. This contrasts with international research, which tends to focus on global environmental issues, whereas Chinese research emphasizes localized case studies. Our analysis identifies a notable gap in Chinese research’s understanding and study of environmental governance experiences. It is recommended to strengthen the role of environmental sociology throughout the governance process from public opinion collection to policy formulation, policy implementation, dynamic feedback, and post-implementation evaluation.

1. Introduction

China has made significant progress in environmental protection, demonstrating substantial strides in ecological civilization construction and environmental governance. This includes the introduction of multiple reform plans related to ecological civilization construction and the establishment of the Central Environmental Protection Inspectorate system. Additionally, the government has formulated an ecological and environmental protection responsibility list applicable to central and state agencies. Several laws and regulations, such as the Environmental Protection Law and Environmental Protection Tax Law, have been amended or enacted. Moreover, numerous national standards on environmental quality, emissions, and monitoring methodologies have been developed. However, despite these improvements, rapid economic development has led to persistent and new environmental challenges, such as air and water pollution, soil degradation, and biodiversity loss, which pose serious threats to sustainable development [1,2,3,4].

Historically, the study of environmental issues has primarily been within the realm of natural sciences, with research primarily focusing on technological innovations, pollution control, and ecological restoration [5]. While these efforts have yielded substantial results, they often overlook the complex social dimensions underlying environmental issues. As environmental problems have evolved, the academic community has gradually realized that a purely natural science perspective is no longer sufficient. Consequently, the sociological attributes of environmental issues, long overlooked, are now gaining more attention [6]. Environmental sociology emerged to bridge this gap, emphasizing how social structures, governance, and public participation shape environmental outcomes. The discipline initially gained prominence in the 1970s with Catton and Dunlap’s “New Ecological Paradigm” and has since evolved into a crucial field of study worldwide. China’s approach to environmental governance has been shaped by its historical context and development path. Initially, the government relied on administrative and technological measures to control pollution, while overlooking the social roots of environmental issues, such as the uneven distribution of resources, regional development imbalances, and limited public participation. For instance, in the early stages of environmental policymaking, there was little focus on community-based governance or public participation, and the role of local governments in addressing environmental justice issues remained minimal [7,8]. Public environmental awareness remained low, and the government’s focus on economic growth further constrained the role of environmental sociology. Although this approach achieved some short-term successes, it failed to address the underlying complexities of environmental governance. The modernization of governance now demands interdisciplinary perspectives, yet the role of environmental sociology in this process remains underexplored.

As China enters a critical phase of environmental governance modernization, the lack of a strong sociological perspective in policymaking could hinder the country’s ability to achieve long-term sustainability goals. Existing research on environmental sociology in China has largely focused on qualitative analyses, case studies, and theoretical discussions, lacking systematic, quantitative assessments of research trends and academic contributions. Against this backdrop, three critical questions arise. Has environmental sociology effectively contributed to environmental governance historically? What are the key differences between Chinese and international environmental sociology research? How can environmental sociology better integrate interdisciplinary perspectives to strengthen its role in modern environmental governance? Addressing these questions is not only academically significant but also practically urgent, as China faces increasing pressure to balance economic growth with environmental sustainability and social equity. Without a robust sociological perspective, environmental governance risks becoming fragmented and ineffective, failing to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Building on these critical questions regarding environmental sociology’s role in governance, it is noteworthy that both the Chinese and the international literature lack comprehensive quantitative analysis of the field. To addresses this gap, this study conducts a bibliometric analysis of the environmental sociology literature from two major databases: the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection (1972–2023) and the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) (1990–2023). Unlike previous studies that primarily rely on qualitative reviews, this study adopts a bibliometric approach to systematically and quantitatively analyze environmental sociology research. This study specifically focuses on analyzing the evolution of the field, identifying key trends, and comparing Chinese and international research to reveal gaps in both theoretical and empirical research. The analysis examines research status and development paths and compares research hotspots, trends, and scholarly contributions between Chinese and international researchers. This comparative approach provides valuable insights into the development of environmental sociology research in China while identifying current shortcomings in the field. This study contributes to the literature through the following contributions: (1) providing the first longitudinal bibliometric analysis of environmental sociology research in China, highlighting trends, key contributors, and knowledge gaps; (2) identifying the tension between the internationalization of Chinese research and the homogeneity of disciplinary backgrounds, offering new insights into the development of the field; and (3) proposing to integrate environmental sociology into interdisciplinary environmental governance strategies to promote more effective decision making and social participation.

2. Literature Review

The development of environmental sociology began in the 1950s, alongside environmental political science. It was driven by numerous environmental disasters, such as the Donora Smog in the United States, the London Smog, and Minamata disease in Japan [9]. By the late 1960s, the environmental protection movement called for governmental intervention to address and control environmental pollution. In the 1970s, scholars from various disciplines, including demography [10,11], rural sociology [12], development sociology [13], and political science [14], explored the “environment-society” relationship from their respective fields, culminating in 1978 with Catton and Dunlap’s publication of “Environmental Sociology: New Paradigm” in “American Sociologist”, which marked the establishment of environmental sociology as a distinct discipline [15]. The interest in environmental sociology resurged in the early 1990s, driven by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. This revival reignited research enthusiasm and solidified the role of new human ecology—an interdisciplinary field that integrates social science theories and methodologies to explore the complex interactions between human spiritual and material civilizations and the natural environment—as a theoretical core, guiding empirical, critical, and global/regional studies within the field [16]. As environmental sociology research expanded globally, scholars increasingly focused on environmental governance in developing countries, including China.

Environmental sociology was introduced to China in 1982 through the article “Environmental Sociology and its Basic Analytical Structure” [17]. The discipline further developed with the establishment of the “Population and Environmental Sociology Professional Committee” by the Chinese Sociological Association in 1992, aimed at promoting research and practice. During the 1990s, several studies were published [18,19], laying the foundation for the discipline’s growth. In 1999, Hong Dayong used the typological approach (a methodological framework that categorizes and compares different types of social phenomena to reveal their underlying patterns and characteristics) to study environmental sociology for the first time, marking a significant step in the development of the field’s structure and identity [16]. Entering the 21st century, environmental sociology research in China expanded rapidly, with the emergence of local theories, such as the social transformation paradigm (a framework analyzing how rapid industrialization, urbanization, and marketization in China shape environmental issues and risks) [20], the rational dilemma (a concept describing the conflict between individual rationality and collective rationality in environmental behavior, where short-term economic interests often override long-term environmental concerns) [21], secondary anxiety (a social psychological phenomenon reflecting public anxiety not only about environmental problems themselves but also about the lack of social trust and amplified risk perceptions) [22], and the integrated development mechanism of politics and the economy (a model highlighting how local governments prioritize economic growth over environmental protection through politically driven development strategies, exacerbating environmental degradation) [23]. According to Lu et al. [24], these theories were based on Chinese experiences and characterized by compatibility, multi-level analysis, and diverse perspectives. The main research areas during this period focused on the social causes of environmental pollution, environmental awareness among urban and rural residents, and the environmental resistance of affected communities [25]. Despite its growth, environmental sociology in China faces two major challenges: (1) a lack of interdisciplinary integration, leading to a relatively homogeneous disciplinary background, and (2) a tension between the internationalization of research and localized theoretical development.

3. Materials and Methods

Given the differences in the citation formats exported by CNKI and WoS, we conducted separate analyses to compare Chinese and international research. Using “Environmental Sociology” as the primary search term, we systematically screened research papers in both databases. In CNKI, a search was conducted for publications from 1990 to 2023 using the term “Environmental Sociology”, initially yielding 342 documents. After manually screening to exclude conference overviews, calls for papers, prefaces, personal academic achievement reports, and irrelevant documents, 249 relevant papers remained. For the WoS Core Collection, a search was performed with the formula TI = (“environment*”) AND TI = (“sociology” OR “social”), restricting the search to six relevant discipline categories: environmental studies, environmental sciences, green sustainable science technology, management, ecology, and sociology. This search, spanning from 1990 to 2023, yielded 3867 relevant papers after excluding off-topic articles.

To ensure a clear analytical framework, we structured our review by distinguishing between two levels of research: global and domestic. The WoS dataset provides a global perspective, encompassing research from multiple countries, including China’s contributions to international journals. In contrast, the CNKI dataset represents China’s domestic scholarly discourse in environmental sociology, reflecting local academic development, policy orientations, and governance models. This distinction allows us to analyze global trends while also capturing the unique characteristics of environmental sociology research within China.

Our results are presented in two parts. First, we examine the global landscape using the WoS dataset, focusing on publication trends, institutional and national distributions, research hotspots, and emerging themes, including China’s presence in international journals. Second, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the CNKI dataset, identifying the evolution of domestic research, core institutions, and thematic focuses, which are shaped by China’s sociopolitical and environmental contexts. By adopting this dual-level approach, we provide a comprehensive overview of both global and local research trajectories in environmental sociology.

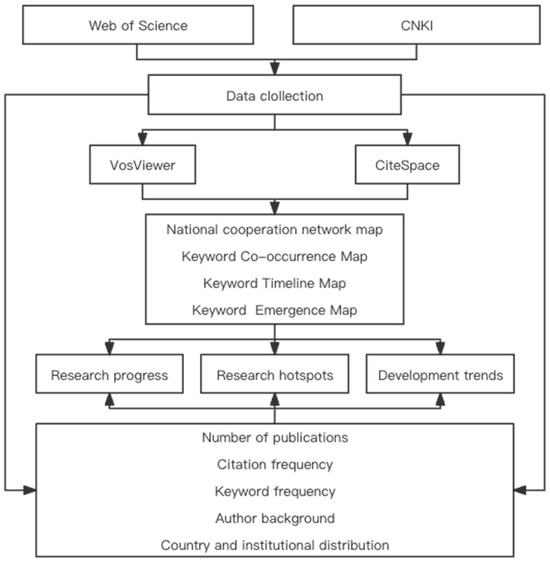

Figure 1 illustrates the research framework. CiteSpace (6.2.R4) and VOSviewer (1.6.18) were used for statistical analysis of key indicators, such as annual publication volume, authors, institutions, countries, citation frequency, keywords, etc., enabling us to analyze the current status, hotspots, and development trends of environmental sociology through visual analysis of knowledge maps and intuitive interpretation of data charts.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

4. Results

4.1. WoS Knowledge Mapping

4.1.1. Annual Publication Trends

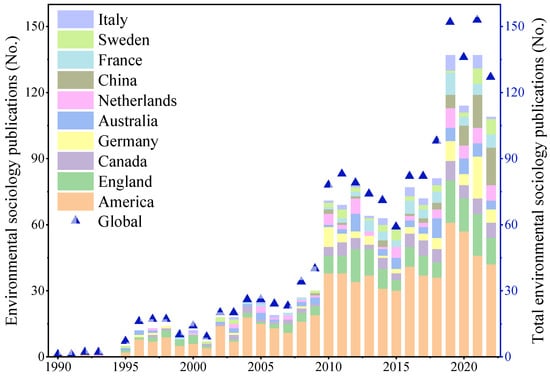

Publication volume is a key indicator for assessing the progress and development of research in a specific field over time. It reflects the level of attention that scholars devote to that field [26]. Global publications in environmental sociology initially increased and later stabilized (Figure 2). From 1972 to 2023, 130 countries contributed to the field, with the United States leading (1085 articles, 28.1%), followed by England (8.43%). Other countries with 150 or more publications are China, Australia, Canada, and Spain. Despite China’s relatively high output, its lower citation rate suggests a limited research impact (Table 1), which may indicate that the quality of Chinese publications is lower compared to top research papers.

Figure 2.

Changes in the ranking of the top 7 countries by publication volume.

Table 1.

Top 10 countries based on the number of articles.

Publication trends show sustained growth across the top ten countries, peaking globally at 314 articles in 2021 (Figure 2). China’s publications volume sharply increased after 2017, reflecting a growing national interest in sociological approaches to environmental issues. However, despite this upward trajectory, the discipline remains on the periphery of mainstream environmental research in China. While there is increasing attention to climate change and growing familiarity with international environmental sociology theories, the discipline has yet to establish itself as a central approach in Chinese environmental research.

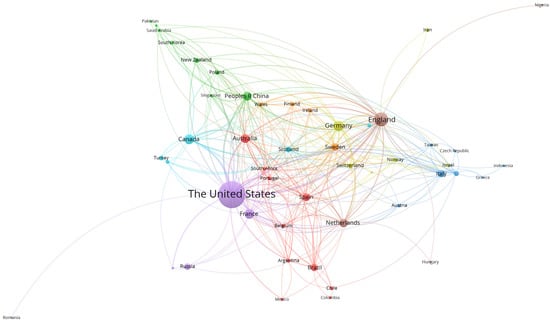

4.1.2. Countries’ Cooperation Networks

Fifteen countries have published 50 or more papers in the field of environmental sociology research. In Figure 3, the nodes’ sizes reflect publication volume, colors denote collaboration clusters, and connection thickness indicates collaboration strength. The 40 nodes represent countries with at least 20 publications. The results reveal major collaboration clusters centered around the United States, England, China, Australia, and Canada (Figure 3), which is consistent with trends in other disciplines where geographically proximate countries collaborate more frequently. Additionally, highly productive countries often play a central role within international collaboration networks [27,28]. This cross-border cooperation has not only fostered the diversified development of environmental sociology theory but also directly influenced the formulation and implementation of environmental policies in various countries.

Figure 3.

Countries’ cooperation networks.

4.1.3. Institutional Analysis of Publications

Statistical analysis of publishing institutions reveals the distribution of research output among different entities. The top ten institutions (Table 2) contribute 441 publications, accounting for 11.4% of the total output. Among these, seven are from the United States, with one each from England, France, and Australia, highlighting the high level of attention this field receives from U.S. research institutions. The University of California leads in publication volume. The top ten institutions average 40.85 citations per article, with only four U.S. universities and one from Australia exceeding this average. Notably, Deakin University in Australia has the highest average citations per paper. There is a significant gap in research impact among U.S. institutions. For instance, the University of North Carolina and the University of Michigan both have average citation counts exceeding 50, making them major hubs for environmental sociology research in the United States.

Table 2.

Top 10 institutions by publication volume in WoS.

4.1.4. Research Hotspots

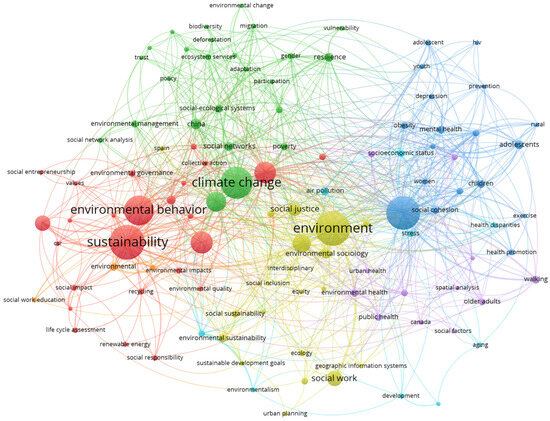

Keywords succinctly summarize the main content of the literature, and their relevance reveals the intrinsic connections of knowledge within the discipline. They are commonly used to analyze emerging trends in a research field [29]. During the analysis, the basic keywords, such as “environment”, “sociology”, “social”, and “environmental sociology”, were excluded from the rankings. Table 3 presents the top fifteen keywords by frequency, with the top five being “sustainability”, “climate change”, “environmental behavior”, “management”, and “policy”. However, within the framework of environmental sociology research, these keywords represent broad concepts and do not reflect specific research directions. Keyword combinations derived from co-occurrence relationships provide a better reflection of the hot research topics in the field.

Table 3.

Top 10 keywords by frequency.

Through the analysis of the keywords’ co-occurrence, as shown in Figure 4, the overall network structure appears relatively loose (density = 0.0198). Each node in the network represents a keyword, with larger nodes indicating higher keyword frequency. The different colors in the keyword co-occurrence network represent clustering categories, dividing the keywords into seven groups. An in-depth analysis of specific nodes in the co-occurrence network reveals that the primary research areas in environmental sociology include environmental sociology theory and methods [30,31,32,33], sustainable development [31,34,35,36,37] and environmental change [38,39,40,41], environmental conflicts [42,43,44] and environmental justice [45,46,47,48,49], ecological modernization [50,51,52], environmental governance [53,54,55], environmental policy [56,57,58,59], and environmental capitalism [60,61], among others. These topics are closely related to global environmental governance.

Figure 4.

Keywords’ concurrence networks.

4.1.5. Burstiness Analysis

Keyword emergence refers to the rapid increase in the frequency of a particular keyword over a specific period, indicating that the keyword, to some extent, represents the forefront of the field [62]. Table 4 presents the top 20 emerging keywords in WoS, with the red portions indicating the periods during which these keywords were considered hot topics. Based on the emergence time of keyword hotspots, their frequency, and the publication trends, international environmental sociology research can be divided into four stages:

Table 4.

Top 20 keywords with emerging trends.

- The Rise and Dilemma of Disciplines (1972–1989)During this period, the significant emerging keyword was “Paradigm”. The early 1970s witnessed the rise of environmental sociology research, particularly following the 1978 publication of “Environmental Sociology: A New Paradigm”, which challenged traditional sociology paradigms. However, by the early 1980s, the field entered a difficult transitional period.

- Cognitive Development Stage (1990–2008)Six emerging keywords define this stage: behavior, attitude, policy, ecological modernization, risk, and health. Research during this period expanded to include social groups’ cognition, attitudes, and behaviors regarding environmental issues. The concept of sustainable development gained widespread attention at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, leading to increased research interest in balancing economic development with environmental protection and social justice. Additionally, the concept of ecological modernization emerged during this time. In the 1990s, growing awareness of the “risks” associated with environmental issues led to increased research on their impact on human health.

- In-Depth Research Stage (2009–2013)Five emerging keywords characterize this stage: inequality, multilevel analysis, politics, environmental impacts, and issues. Research methods are diversified, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches, such as surveys, field observations, and statistical analyses. Interdisciplinary research increased, with collaboration across disciplines like economics, political science, and psychology. Scholars deepened their understanding of environmental risks, environmental justice, and the relationship between environmental values and behavior. Particular emphasis was placed on exploring the essence of environmental injustice and the social mechanisms shaping the understanding of the environment from economic, political, gender, and other perspectives.

- Diversified Development Stage (2013-present)During this stage, eight emerging keywords gained prominence: biodiversity, sustainability, pro-environmental behavior, green, CO2 emissions, energy consumption, renewable energy, and economic growth. Environmental sociology research has taken a more diversified trajectory, focusing on global environmental issues, such as climate change, carbon emissions, and green sustainable development. Additionally, international cooperation and interdisciplinary collaboration have become hallmarks of this stage, addressing complex environmental and social issues through communication and cooperation.

4.2. CNKI Knowledge Mapping

4.2.1. Annual Publication Trends

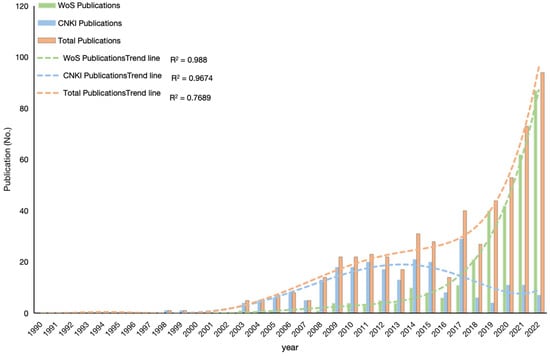

From 1990 to 2022, a total of 249 publications on environmental sociology were recorded in CNKI after screening. To ensure comprehensive research data, 317 relevant documents were extracted from the WoS Core database by filtering for “PEOPLES R CHINA” within the 3867 collected records. Overall, the number of publications related to environmental sociology in China shows an increasing trend. Specifically, the CNKI publications initially rose before declining, while WoS publications grew exponentially. The years 2017 and 2021 stand out as high-frequency years for Chinese scholars’ research on environmental sociology. Since 2009, there has been a growing trend of publishing in international journals, accelerating after 2017 (Figure 5). Despite this progress, the total number of publications in environmental sociology remains relatively low, which is disproportionate to the severe ecological and environmental challenges the country faces. This phenomenon suggests that environmental sociology has not yet become a central think tank supporting environmental governance in China.

Figure 5.

Annual number of publications and trends in Chinese environmental sociology.

4.2.2. Authors’ Cooperation Networks

Chinese scholars in environmental sociology tend to conduct more independent studies, with only a few engaging in collaborative research. Analysis reveals that the top five authors with the most publications are Hong Dayong (15 articles), Cui Feng (11 articles), Chen Tao (9 articles), Lin Bing (8 articles), and Chen Ajiang (8 articles). Several research teams have emerged within the Chinese environmental sociology community. The research team led by Zhang Bo is the largest, consisting of 13 researchers, while the team led by Hong Dayong, though smaller, has produced prolific research outcomes. Other notable teams, with core members including Chen Ajiang, Lin Bing, Cui Feng, Chen Tao, Lu Chuntian, and Wang Shuming, also stand out in terms of collaboration and research achievements. Beyond the core authors, numerous peripheral structures have emerged, formed by independent scholars publishing individually. Most research is still centered around individual scholars. The limitations of this collaboration model have significantly affected the depth of research and the effectiveness of academic dissemination.

This research organized the data on the top 10 Chinese scholars with the highest publication volumes, including their doctoral graduation years, academic backgrounds, and primary research directions, as shown in Table 5. The range of doctoral graduation years spans from 1997 to 2018, reflecting the diverse characteristics of environmental sociology scholars in China across different periods. Preliminary findings include the following. Most scholars have academic backgrounds in philosophy and sociology, with many working in sociology departments at universities. Some have backgrounds in history, literature, and education, while only a few have academic backgrounds in environmental science. Despite earning their doctoral degrees domestically, many Chinese scholars exhibit strong interest in researching international classical theories of environmental sociology, as reflected in their abundant literature contributions.

Table 5.

Background information of the top 10 Chinese authors.

4.2.3. Institutional Analysis of Publications

According to the statistics, the top ten research institutions publishing environmental sociology literature are listed in Table 6. The CNKI literature includes contributions from 213 research institutions. The top three institutions in terms of publication volume are the Renmin University of China (34 articles), Hohai University (30 articles), and the Ocean University of China (27 articles), each publishing more than 25 articles, accounting for 15.96%, 14.08%, and 12.68% of the total, respectively. The top ten research institutions collectively published 143 articles, representing 67.1% of the total publication volume. This highlights the substantial impact these institutions have on the field of environmental sociology in China, with research concentrated among a few leading institutions, although publication levels vary.

Table 6.

Top 10 scientific research units.

4.2.4. Research Hotspots

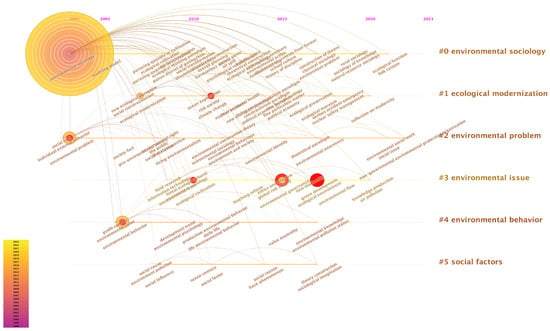

The basic keywords “environment”, “sociology”, and “environmental sociology” were excluded from the ranking during the analysis. Figure 6 represents the timeline graph of keywords in the CNKI-retrieved literature. The top ten keywords with the highest frequencies in CNKI are environmental issues, environmental behavior, China, environmental governance, ecological modernization, ecological civilization, climate change, Japan, social impacts, and environmental pollution. From the ranking of keyword frequencies, it is evident that environmental sociology research is primarily focused on the governance of environmental issues, particularly climate change and ecological modernization. Based on the timeline of keywords’ distribution, the recent Chinese literature (post-2018) highlights environmental governance, sustainable consumption, modernization, environmental awareness, daily life, and green development as the dominant research topics.

Figure 6.

Timeline graph of keywords.

Keyword clustering categorizes research directions, with Q representing the modularity value and S as the average silhouette value. Generally, a modularity value Q > 0.3 indicates a significant clustering structure, and a silhouette value S > 0.7 suggests high reliability of the clustering results. After analyzing the CNKI literature, the obtained values were Q = 0.8655 and S = 0.9691, indicating a reliable clustering result. The top six keyword clusters in terms of the number of members are shown in Clusters#0–#5 in Figure 6. Combining the clustering results with an in-depth analysis of representative papers for important keyword nodes in the network diagram reveals that the Chinese environmental sociology literature primarily focuses on the relationship between the environment and society, the social factors influencing environmental issues, and their social consequences. This includes social causes of environmental pollution [20,63], environmental awareness among urban and rural residents [64,65], environmental resistance by victims [66,67], environmental justice and equity [68,69], ecological migration [70,71], and environmental policy [72,73].

Although topics like environmental justice, public participation, and policymaking are present among research hotspots, they remain underexplored and lack practical application, highlighting the underutilization of environmental sociology in governance practices. For example, the 2005 Songhua River pollution incident triggered public concern over environmental risk governance, but the role of environmental sociology was nearly absent. Delayed information disclosure and widespread public panic emphasized the failure of sociological theories to guide risk communication and manage public emotions. Furthermore, most subsequent studies have focused on engineering and technological aspects, with few exploring social collaboration and changes in public behavior during the governance process. Additionally, the 2007 Xiamen PX project public protest revealed that the need for public participation in major environmental decision making has long been overlooked. Although domestic environmental sociology research covers topics like environmental risks and public participation, it has not provided direct theoretical support for governance in such events. The lack of social research and public communication mechanisms prior to decision making contributed to the escalation of the event into mass protests.

4.2.5. Burstiness Analysis

Table 7 presents the top 15 emerging keywords in CNKI, with the red portion indicating the periods during which these keywords were considered hot topics. Research on environmental sociology in China can be divided into three stages.

Table 7.

Analysis of burstiness based on the CNKI database, ranked by the beginning year of the burst.

(1) Initial Stage (1990–2006): This stage features five emerging keywords: “sociologist”, “branch discipline”, “sociology”, “environmental science”, and “research paradigm”. During this period, environmental sociologists mainly focused on compiling and summarizing relevant international research during this period.

(2) Rapid Development Stage (2007–2013): In this stage, scholars focused on local experiences and the social causes and consequences of environmental pollution. Three emerging keywords included “environmental behavior”, “climate change”, and “farmers”. Following the first China International Symposium on Environmental Sociology in 2007, Chinese environmental sociology saw rapid development, with the publication volume gradually rising to its peak.

(3) Accelerated Development Period (2014–present): This stage includes six emerging keywords: “environmental governance”, “Japan”, “China”, “environmental identity”, “ecological civilization”, and “modernity”. This period marks accelerated development, as Chinese scholars have explored a wide range of topics, particularly environmental governance and policy development and practical analyses.

5. Discussion

The WoS and CNKI databases, as the primary platforms for disseminating research results, exhibit both differences and similarities in terms of publication volume, contributing countries, contributing institutions, research hotspots, and research frontiers. To compare the current research status in China and internationally, the literature originating from China in the WoS database is categorized as Chinese literature.

5.1. Publishing Internationalization and Disciplinary Constraints: Challenges for Policy Implications

From 1972 to 2023, Chinese and international publications followed distinct patterns. Both showed general growth from 1972 to 2011, with Chinese literature continuing on a variable upward trend until 2017. After nearly a decade of development, Chinese scholars increasingly shifted towards publishing in international journals. This shift became particularly evident after 2017, when publications in Chinese journals declined while international publications rose. An increasing number of Chinese scholars have chosen to publish in international journals, driven by the pursuit of global influence. While this enhances China’s standing in the international environmental sociology community, it creates a paradox: the prioritization of global academic discourse inadvertently marginalizes research addressing China’s specific policy contexts. As scholars align their topics with the preferences of international journals, China’s policy-relevant studies risk being underdeveloped. In addition, the key findings published in English remain inaccessible to many local policymakers due to language barriers.

At the same time, another challenge has also emerged. This study indicates that most scholars have academic backgrounds in philosophy and sociology, with many working in sociology departments at universities. Some have backgrounds in fields like history, literature, and education, while only a small number have academic backgrounds in environmental science. This disciplinary silo restricts the field’s ability to address complex environmental governance challenges that require interdisciplinary insights.

5.2. Research Institutions’ Strengths: The Role of Chinese and International Universities

Universities lead environmental sociology research globally. Analysis of the average citation frequency reveals that Chinese institutions’ research impact lags behind that of their counterparts in the United States, England, France, and Germany. This gap is highlighted by the absence of Chinese institutions among the top 10 publishing institutions in the WoS database. Chinese research institutions must intensify efforts to improve the quality and impact of their literature and promote their research on a global scale. To elevate China’s standing in the field, research institutions need to prioritize enhancing research quality and fostering global collaboration, aiming not only to increase the quantity of publications but also to influence global environmental policy discourse. This is especially crucial, as environmental sociology plays a pivotal role in addressing global environmental issues.

5.3. From Keyword Disparities to Practical Gaps: Comparison of Chinese and International Studies

The differences in high-frequency keywords reflect the distinctions in research directions and dimensions between the Chinese and the international literature. While shared topics, such as climate change, governance, and environmental justice, appear in both the WoS and the CNKI databases, notable distinctions are evident in their specific focus areas. Keywords, such as “ecological civilization”, “localization”, and “farmer resistance”, appear more frequently in CNKI, reflecting China’s unique sociopolitical context, policy-driven research orientation, and cultural characteristics. These topics indicate that Chinese environmental sociology tends to focus on localized case studies, which are less prominent in the WoS literature. Additionally, the earlier rise of environmental sociology research abroad has influenced China’s focus on international studies. In terms of timing, keywords, such as “environmental governance”, “sustainable consumption”, “environmental policy”, and “ecological modernization”, emerged later in the Chinese literature. Compared to international research practices, where environmental sociology is directly involved in the environmental governance process, Chinese research tends to emphasize theoretical aspects, with fewer practical interventions in governance. An example of this is the ecological governance of the Yangtze River Basin, which illustrates the limited role of environmental sociology in China’s environmental efforts. Despite emphasizing cross-regional collaboration, the field failed to provide concrete support in areas like local social interest negotiations and the design of public participation models. This has led to suboptimal regional cooperation and low public participation in the governance process. In contrast, international environmental sociology scholars emphasize guiding public behavior and researching risk perception, creating an effective pathway that combines theory with practice. China’s 2013 air pollution governance campaign demonstrated that despite strong policies and efforts, environmental sociology played a limited role in changing public behavior. Instead, policy implementation relied on administrative mandates rather than active public participation.

Structural factors, such as China’s policy-driven research tradition and language barriers in international academic communication, may explain variations in scholarly focus and global impact. For instance, China’s prioritization of domestically relevant policy research has fostered an emphasis on localized case studies, which may align less with the thematic preferences of international journals. Additionally, language constraints often hinder Chinese scholars’ integration into global academic networks, while differences in institutional incentives, such as evaluation criteria favoring local relevance over international engagement, may further reinforce a focus on region-specific issues rather than globally oriented scholarship.

This phenomenon reflects that China’s early environmental governance relied primarily on administrative orders and technical solutions, neglecting social research and intervention. As a result, the role of environmental sociology has been limited, especially in responding to major environmental incidents, where policy responses prioritize emergency measures and technical fixes over addressing the social roots of issues. The field’s late development and limited practical application in China contrast sharply with international examples. In Japan, environmental sociology research following the Minamata disease incident prompted the government to recognize the social costs of industrial development, leading to stricter environmental regulations. Similarly, in the United States, environmental sociology provided crucial support for environmental policy by systematically studying public opinion and participation during environmental movements. These international experiences demonstrate that environmental sociology not only reveals the social roots of environmental problems but also provides scientific evidence to support policymaking.

6. Conclusions

This study presents a bibliometric analysis of the Chinese and international literature on environmental sociology from 1972 to 2023. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Internationalization vs. Localization in Academic Research. Since 1972, China’s environmental sociology research has exhibited a tension between internationalization and localization. While the number of publications in international journals has significantly increased since 2017, publications in Chinese journals have declined, reflecting scholars’ prioritization of international topics to gain global academic recognition. This trend has led to a marginalization of research on local policy issues. Furthermore, language barriers exacerbate this issue, as English-language research is less accessible to domestic policymakers, thereby weakening the direct contribution academic research can make to governance. The lack of interdisciplinary integration, with over 80% of research rooted in philosophy and sociology and limited cross-over with environmental sciences, restricts the ability to address complex environmental governance challenges, highlighting the need for interdisciplinary collaboration.

(2) Disparity in Institutional Influence. While Chinese universities dominate publications in Chinese journals (e.g., Renmin University, Hohai University, and the Ocean University of China account for 42.72% of the total), their international academic influence remains significantly lower. No Chinese institution is ranked among the top 10 in the WoS database, and the citation rate per article is lower than that of leading institutions in Europe and the U.S. This gap reflects a structural weakness in Chinese research, characterized by an emphasis on quantity over quality and a focus on local rather than international issues. To enhance global academic influence, a dual approach is needed: first, research depth should be strengthened by promoting mutual learning between environmental science and social science methodologies; second, international cooperation networks must be expanded, moving beyond the current “center-periphery” model dominated by the U.S., UK, and Australia, to actively participate in global environmental policy discussions.

(3) The Gap Between Theory and Practice. The thematic differences between the Chinese and the international literature reflect distinct research paradigms; international research tends to focus on global issues, such as climate change and risk perception, emphasizing theoretical guidance of practical applications (e.g., public participation in environmental movements in the U.S.), while Chinese research concentrates on local issues, such as ecological civilization and environmental protests, often stopping at theoretical explanation and case studies. A typical example is the ecological governance of the Yangtze River Basin, where academia has failed to provide practical solutions, such as cross-regional interest negotiation mechanisms, resulting in governance that remains at the administrative level. In contrast, international examples, such as policy transformation following Minamata disease in Japan and the use of public behavior research to improve environmental policies in the U.S., show how academic research can drive policy change. In China, a significant “last mile” barrier exists in translating theory into practice. Contributing factors include an academic evaluation system that encourages local policy research but hinders international dissemination, language barriers that restrict two-way knowledge flow, and an academic tradition that is overly reliant on philosophical speculation and neglects empirical intervention.

To address these issues, three key reforms are needed. First, establish a “policy-oriented internationalization” mechanism. This should encourage scholars to engage in international dialogue based on China’s environmental governance practices, rather than passively adapting to Western agendas. Second, reconstruct the academic training system. By cultivating sociologists in environmental science fields, China can break away from the traditional discourse of environmental sociology, enhance academic dialogue, and avoid a one-dimensional approach to methodologies. Finally, environmental sociology should align with national strategic needs and key tasks. Environmental sociology should play a critical role in responding to China’s “dual carbon” goals and the ongoing battle against pollution. The discipline should strengthen its role throughout the entire governance process, from public opinion collection and policy development to implementation, dynamic feedback, and post-implementation evaluation, thus effectively contributing to the modernization of environmental governance.

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, visualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, visualization, methodology, data curation, Y.F.; writing—review and editing, methodology, data curation, T.W.; writing—review and editing, methodology, R.L.; writing—review and editing, data curation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, visualization, S.P.; writing—review and editing, X.W.; writing—review and editing, methodology, project administration, funding acquisition, P.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is support by the National Key R&D Program of China [grant number 2023YFE0113105], the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution [grant number 2024YSKY-24; 2021YSKY-01].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNKI | The China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| WOS | The Web of Science |

References

- Liu, J.; Yang, W. Water sustainability for China and beyond. Science 2012, 337, 649–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. China’s wastewater treatment goals. Science 2012, 338, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y. China’s fight against soil pollution. Science 2018, 362, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wang, M.; Duan, M.; Ma, X.; Hong, J.; Xie, F.; Zhang, R.; Li, X. In search of key: Protecting human health and the ecosystem from water pollution in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D.P.; Hull, R.B. Public ecology: An environmental science and policy for global society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2003, 6, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, J. Environmental Sociology; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. Environmental disputes in China: A case study of media coverage of the 2012 Ningbo anti-PX protest. Glob. Media China 2017, 2, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Ho, M. The Maoming Anti-PX protest of 2014. An environmental movement in contemporary China. China Perspect. 2014, 2014, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, Y.; Sun, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, Q.S.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, G. Environmental pollution, a hidden culprit for health issues. Eco-Environ. Health 2022, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, J.B. Daydreams and Nightmares: A Sociological Essay on the American Environment (Book Review). Rural Sociol. 1972, 37, 267. [Google Scholar]

- Catton, W.R., Jr. Can irrupting man remain human. BioScience 1976, 26, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, J.H. Rural sociology and rural development. Rural Sociol. 1972, 37, 515. [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, G. Themes and Issues in Sociological Theories of Human Aging. Hum. Dev. 1970, 13, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, W.A. On the Concept of Ideology in Political Science. Am. Politi-Sci. Rev. 1972, 66, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, W.R., Jr.; Dunlap, R.E. Environmental sociology: A new paradigm. Am. Sociol. 1978, 13, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Catton, W.R. Struggling with human exemptionalism: The rise, decline and revitalization of environmental sociology. Am. Sociol. 1994, 25, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catton, W.R., Jr.; Dunlap, R.E. Environmental Sociology and Its Basic Analytical Structure. Abstr. Mod. Foreign Philos. Soc. Sci. 1982, 11, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G.Q. Social and Cultural Views on Environmental Research. Sociol. Res. 1993, 5, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.H. Sociological Research on Urban Ecological Environment Issues: Environmental Pollution and Resident Location Distribution in Benxi City. Sociol. Res. 1994, 6, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.Y. Social Change and Environmental Issues; Capital Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Rational Dilemma: An Analysis of the Social Roots of Environmental Issues in the Transitional Period from the Perspective of Environmental Behavior. J. East China Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2007, 1, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A. Secondary Anxiety: A Social Interpretation of Water Pollution in the Tai Lake Basin; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L. China’s Experience in Environmental Resistance. Xuehai 2010, 2, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.T.; Ma, S.C. Overview and Comparison of Environmental Sociology Theories in China and Japan. J. Nanjing Tech Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 3, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.T.; Deng, L.; Wu, J.F.; Li, Q.; Yang, H.C. A Decade of Reflection on Chinese Environmental Sociology. J. Hohai Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 2, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rui, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zuo, J.; Tong, Y. Sources of atmospheric pollution: A bibliometric analysis. Scientometrics 2017, 112, 1025–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Qiu, L.; Wei, S.; Zhou, H.; Bathuure, I.A.; Hu, H. The spatiotemporal evolution of global innovation networks and the changing position of China: A social network analysis based on cooperative patents. RD Manag. 2024, 54, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Nie, C.; Shi, Z.; Wang, X.; Gao, Z. A bibliometric analysis of micro/nano-bubble related research: Current trends, present application, and future prospects. Scientometrics 2016, 109, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Li, J.; He, M.; Li, J.; Zhi, D.; Qin, F.; Zhang, C. Global evolution of research on green energy and environmental technologies: A bibliometric study. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.B. Marx’s theory of metabolic rift: Classical foundations for environmental sociology. Am. J. Sociol. 1999, 105, 366–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, W.A. Hierarchy Theory in Sociology, Ecology, and Resource Management: A Conceptual Model for Natural Resource or Environmental Sociology and Socioecological Systems. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2005, 18, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Biga, C.F. Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 398–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerecnik, K.R.; Andersen, P.A. The diffusion of environmental sustainability innovations in North American hotels and ski resorts. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Baumann, H.; Hall, J. Conceptualizing sustainable development and global supply chains. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 83, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.R. Sustainable development: Agents, systems and the environment. Curr. Sociol. 2016, 64, 875–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.X.; Sinha, P.N.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.-K. The role of environmental justice in sustainable development in China. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, E.A.; Dietz, T. Climate change and society: Speculation, construction and scientific investigation. Int. Sociol. 1998, 13, 421–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearley, S. Sociology and climate change after Kyoto: What roles for social science in understanding climate change? Curr. Sociol. 2009, 57, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoville, C.; McCumber, A. Climate Silence in Sociology? How Elite American Sociology, Environmental Sociology, and Science and Technology Studies Treat Climate Change. Sociol. Perspect. 2023, 66, 888–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, J. Household consumption and environmental change: Rethinking the policy problem through narratives of food practice. J. Consum. Cult. 2017, 17, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, A.; Lawrence, A. Emotional conflicts in rational forestry: Towards a research agenda for understanding emotions in environmental conflicts. For. Policy Econ. 2013, 33, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centemeri, L. Reframing Problems of Incommensurability in Environmental Conflicts through Pragmatic Sociology: From Value Pluralism to the Plurality of Modes of Engagement with the Environment. Environ. Values 2015, 24, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, T. Toward a constructivist understanding of socio-environmental conflicts. Civ. Wars 2016, 18, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, J.C. Environmental justice in the textbook of sociology. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2021, 30, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. “We don’t really want to know”—Environmental justice and socially organized denial of global warming in Norway. Organ. Environ. 2006, 19, 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvers, H.D.; Gross, M.; Heinrichs, H. The diversity of environmental justice: Towards a European approach. European Societies 2008, 10, 835–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, V.; Gaither, C.J.; Gragg, R.S. Promoting Environmental Justice Through Urban Green Space Access: A Synopsis. Environ. Justice 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M.; Reed, R. Emotional impacts of environmental decline: What can Native cosmologies teach sociology about emotions and environmental justice? Theory Soc. 2017, 46, 463–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.J. Risk society and ecological modernisation alternative visions for post-industrial nations. Futures 1997, 29, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttel, F. Ecological modernization as social theory. Geoforum 2000, 31, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. The Quest for Ecological Modernisation: Re-Spacing Rural Development and Agri-Food Studies. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, H.; Pascual, U. Social capital in community level environmental governance: A critique. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 1549–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frödin, O. Researching Governance for Sustainable Development: Some Conceptual Clarifications. J. Dev. Soc. 2015, 31, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blühdorn, I.; Deflorian, M. The Collaborative Management of Sustained Unsustainability: On the Performance of Participatory Forms of Environmental Governance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juntti, M.; Russel, D.; Turnpenny, J. Evidence, politics and power in public policy for the environment. Environ. Sci. Policy 2009, 12, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tàbara, J.D.; Chabay, I. Coupling human information and knowledge systems with social–ecological systems change: Reframing research, education, and policy for sustainability. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 28, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, N.J.; Alldred, P. Re-assembling climate change policy: Materialism, posthumanism, and the policy assemblage. Br. J. Sociol. 2020, 71, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. Sustainable Consumption: A Theoretical and Environmental Policy Perspective. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2003, 16, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, R. Capitalism, Governance, and Authority: The Case of Corporate Social Responsibility. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2010, 6, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperiale, A.J.; Vanclay, F. The mechanism of disaster capitalism and the failure to build community resilience: Learning from the 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy. Disasters 2020, 45, 555–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, L. Research Progress on Plant Functional Traits Based on CiteSpace. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.J. A Sociological Explanation of Water Pollution. J. Nanjing Norm. Univ. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2000, 1, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.Y. Environmental awareness of urban residents in China. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2005, 1, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Yang, X. Environmental Awareness of Shanghai Citizens: Current Situation, Problems, and Countermeasures. J. East China Univ. Sci. Technol. Soc. Sci. Ed. 2006, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.L. China’s Experience in Environmental Resistance. Study Times 2010, 2, 66–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.Z. Silent Majority: Stratification Pattern and Environmental Resistance. J. Renmin Univ. China 2007, 1, 122–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. Thinking on Transformation and Upgrading from the Perspective of Environmental Justice. Contemp. Econ. Sci. 2013, 35, 21–27+124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sitan, L.I.; Cheng, P.L. Three Dimensions of Environmental Sociology Research: Reinterpretation of Environmental Justice. Environ. Sociol. 2022, 1, 1–17+231–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.Z. A Study on Voluntary and Involuntary Eco-migration—Investigation of Luanjingtan in Inner Mongolia; Central University for Nationalities: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q.Y. Eco-Migration and Community Construction from the Perspective of Environmental Sociology; Central University for Nationalities: Beijing, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Ecology and Life Under Policy Influence; Central University for Nationalities: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Kagawa, Y.I. Environmental Governance and Policy in Lake Poyang: An Exploration from the Perspective of Environmental Sociology. Environ. Sociol. 2023, 1, 141–158+199–200. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).