Evaluation of Ecologically Based Activities Within the Scope of Sustainable Tourism and Recreation Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

- General Command of Mapping 1/100,000 scale topographic maps;

- MTA 1/100,000 scale geological maps and reports;

- General Directorate of Forestry 1/100,000 scale Forest Management Plans and reports of Kumla District of Gemlik District;

- Landsat TM Satellite image dated 1999;

- Domestic and foreign literature data.

2.2. Method

- Landslide Situation: According to the data obtained from the Mineral Research and Exploration General Directorate earth science system, this factor was fixed as “None” since there is no landslide risk within the boundaries of the research area.

- Proximity to water sources: The fact that the research area is very rich in surface waters and that these surfaces are scattered throughout the area allowed the proximity criteria to the water source to be evaluated as constant.

- Wind speed: Although winds from the north and northeast are effective in the area, the average wind speed in summer is calculated as 12.4 km/h. The average wind intensity throughout the year is determined as 6–12 km/h [34]. The average wind intensity prevailing in the area is 6–12 km/h and this range corresponds to the 2–3 class range according to the Beaufort classification. The evaluation factors of this class of events were deemed appropriate for their thresholds and were taken as constant.

- Relative humidity: While the relative humidity rate prevailing in the area is between 10 and 100, this rate drops below 80 in the summer months when recreational activities are carried out, allowing this factor to be evaluated as constant.

- Existence of floodplains: The presence of surface water that will rise to flood level has not been detected in the area. Therefore, this factor was taken as constant.

- Transportation distance: There are stabilized roads, asphalt roads, highways, and pathways in the area, providing access to the area and surrounding settlements. Therefore, this factor was taken as constant.

3. Results

3.1. Determination of Potential Areas for Tent Camping Activity

- Slope: The slope range for “Most Suitable” areas is 0–15. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 6335.75 ha. A total of 79.35% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Exposition: Aspect directions accepted for the “Most Suitable” areas are straight, east, southeast, south, southwest, and west facades. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 7751.29 ha. A total of 97.07% of the area was found suitable for the event. Aspect directions accepted for suitable areas are north, northeast, and northwest.

- Height: The accepted height for “Most Suitable” areas is 0–326 m. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 6719.46 ha. A total of 84.15% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Land ability class: Land ability classes accepted for “Most Suitable” areas are IV, VI, VII, and beach classes. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 7118.12 ha. A total of 89.15% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Current land use: Accepted use types for “Most Suitable” areas are forest, shrubland, dry farming, and coastal dunes. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 5701.9 ha. A total of 71.41% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Natural plant existence: Plant assets accepted for “Most Suitable” areas: deciduous forest, mixed forest, treeless area. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 5383.09 ha. A total of 67.42% of the area was found suitable for the event. Plant assets accepted for “Suitable” areas: areas with coniferous trees. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 264.65 ha. A total of 3.31% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Forest canopy: Forest cover rates accepted for “Most Suitable” areas are 1–10%, 11–40%, and 41–70% cover classes. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 6285.94 ha. A total of 78.72% of the area was found suitable for the event.

3.2. Determination of Suitable Areas for Caravan Camping Activity

- Natural plant presence: Plant assets accepted for “Suitable” areas are open and semi-open areas. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 777.01 ha. A total of 9.73% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Forest canopy: The forest cover rates accepted for the “Most Suitable” areas are 1–10%, and 11–40% cover classes. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 5147.3 ha. A total of 64.46% of the area was found suitable for the event.

3.3. Determination of Suitable Areas for Hiking Activity

- Slope: The slope range for “Most Suitable” areas is 0–8. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 3018.42 ha. A total of 37.8% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Soil drainage: “Most Suitable” areas are areas with good drainage. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 7666.8 ha. A total of 96% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Soil texture: The texture class for “Most Suitable” areas are areas with coarse and medium texture. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 5079.91 ha. A total of 64% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Current land use: The types of use accepted for “Most Suitable” areas are forest and shrubland. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 5171.9 ha. A total of 64.77% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Natural plant presence: It is deemed sufficient to have unrestricted presence of plant assets accepted for the “Most Suitable” areas. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 7711.29 ha. A total of 96.6% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Slope: The slope range for “suitable” areas is 0–12. The area of surfaces that meet this condition in the area is 4118.97 ha. A total of 51.59% of the area was found suitable for the event.

- Soil drainage: “Suitable” areas are those with good and medium drainage. The drainage classes available in the area are good, poor, and inadequate. For this reason, areas representing the “Most Suitable” areas in soil drainage are considered valid among the “Suitable” areas.

- Soil texture: The texture class for “suitable” areas are fields with coarse, medium, and fine texture. Since the soil texture types in the area are medium and fine texture, the entire area meets this condition.

- Current land use: Accepted use types for “suitable” areas are forest, shrubland, pasture, and meadow. Since there are no pastures and meadows in the area and the remaining areas represent the “Most Suitable” areas, these areas are also considered valid for “Suitable” areas.

3.4. Determination of Suitable Areas for Trekking Activity

3.5. Determination of Suitable Areas for Landscape Viewing and Nature Photography Activity

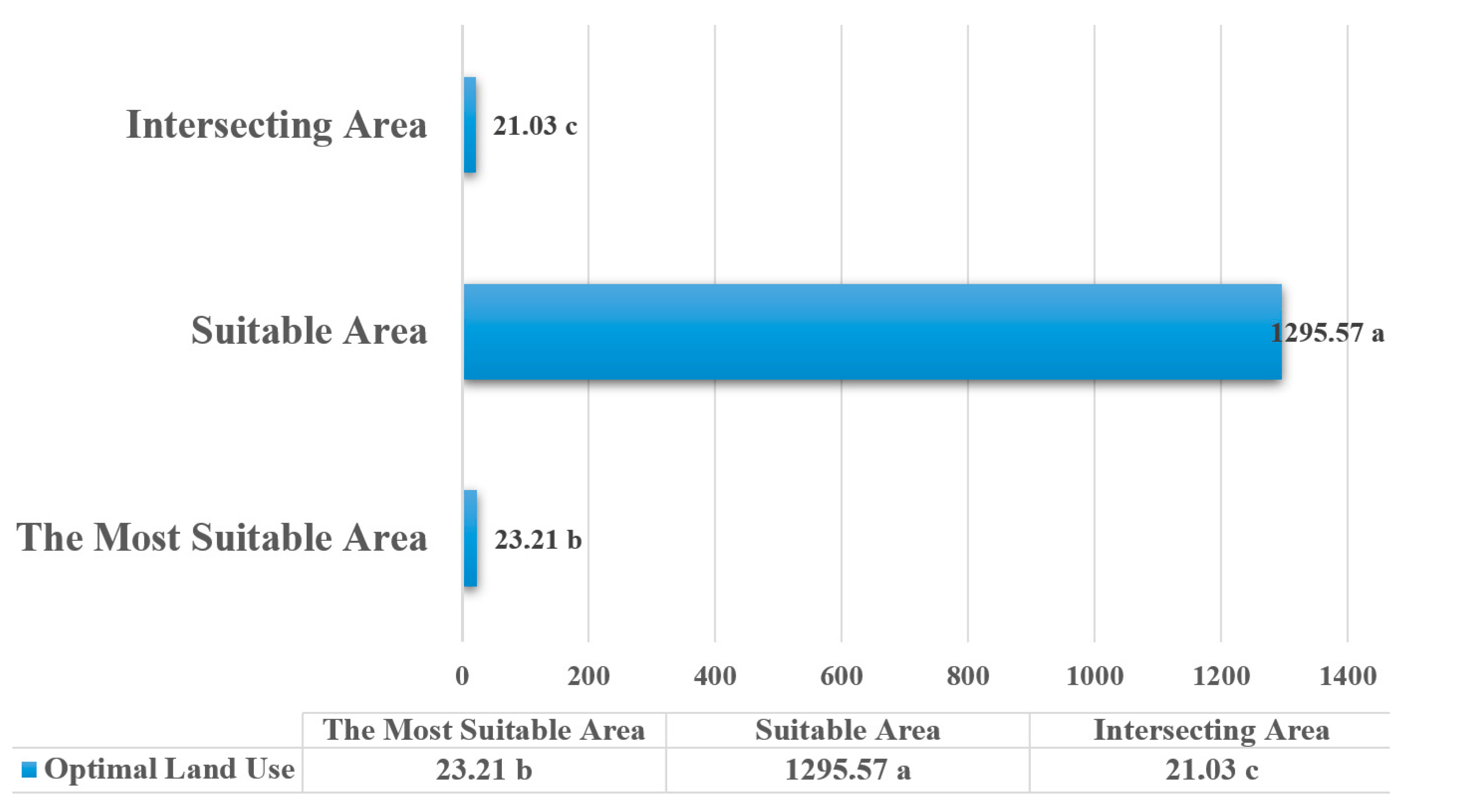

3.6. Optimal Land Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yılmaz, B. Bartın İli ve yakın çevresi peyzaj özelliklerini etkileyen iklim parametrelerinin analizi ve değerlendirilmesi. ZKU J. Fac. For. 2006, 8, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z.; Seyidoğlu Akdeniz, N. An Examination of the Landscape values of some coastal neighborhoods of Bursa-Mudanya in terms of rural tourism possibility. In Theory and Research in Architecture, Planning and Design; Gece Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2020; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fons, M.V.S.; Fierro, J.A.M.; Patino, M.G. Rural Tourism: A sustainable alternative. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Henderson, J.C. Sustainable Rural tourism in Iran: A Perspective from Hawraman Village. Tour. Manag. 2012, 2–3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C. Sustainable Tourism as an Adaptive Paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A. Tourism in rural areas: Kedah, Malaysia. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akış, S. Sürdürülebilir turizm: Bir alan araştırmasının sonuçları. Anatolia J. Tour. Res. 2001, 12, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tuna, M. Turizm, Çevre ve Toplum; Detay Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Day, J.; Cai, L. Environmental and energy-related challenges to sustainable tourism in the United States and China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutawa, G.K. Issues on Bali tourism development and community empowerment to support sustainable tourism development. International conference on small and medium enterprises’ development with theme). Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Evaluating eco-sustainability and its spatial variability in tourism areas: A case study in Lijiang County, China. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2009, 16, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huigin, L.; Linchun, H. Evaluation on sustainable development of scenic zone based on tourism ecological foodprint: Case study of Yellow Crone Tower in Hubei province, China. 2010 International Conference on Energy, Environment and Development—IACEED, 2010. Energy Procedia 2011, 5, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, A.S.; Dowling, R.K. Aspects of Tourism, Natural Area of Tourism; Ecology, Impacts and Management; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Polat, A.T. Karapınar Ilçesi ve Yakın Çevresi Peyzaj Özelliklerinin Ekoturizm Kullanımları Yönünden Değerlendirilmesi Üzerine bir Araştırma. Ph.D. Thesis, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z. Altındere Vadisi (Trabzon-Maçka)’nde Ekolojik Temelli Turizm Planlama Yaklaşımı ve Alternatif Turizm Olanaklarının Araştırılması. Ph.D. Thesis, Karadeniz Teknik University, Trabzon, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Holleran, J.N. Sustainabilty in tourism destinations: Exploring the boundaries of eco-effienciency and green communications. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2008, 17, 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Kent, K.; Sinclair, A.J.; Diduck, A. Stakeholder engagement in sustainable adventure tourism development in the Nanda Devi biosphere reserve. India. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirselimoğlu, Z.; Demirel, Ö.A. study of an Ecology based recreation and tourism planning approach: A case study on Trabzon Calköy high plateau in Turkey. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2012, 19, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhami, I.; Deng, J.; Burns, R.C.; Pierskalla, C. Identifying and mapping forest-based ecotourism areas in West Virginia-incorporating visitors’ preferences. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.K.W.; Jim, C.Y. Segmentation by motivation of Hong Kong Global Geopark visitors in relation to sustainable nature-based tourism. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 22, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pirselimoglu Batman, Z.; Demirel, Ö.; Kurdoglu, B.Ç. Ecology-Based Tourism Potential of Altindere Valley(Trabzon-Turkey) in Regards to the Natural, Historical and Cultural Factors. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z.; Zencirkıran, M. Investigation of nature-based tourism possibilities in Bursa Waterfalls. In Global Issues and Trends in Tourism; St. Kliment Ohridski University Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 650–661. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S.; Esbah, H.; Akgün, A.A. Quantitative SWOT analysis for prioritizing ecotourism-planning decision in protected areas: Igneada case. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 23, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacki, M.; Kowalczyk-Anioł, J.; Królikowska, K.; Pstrocka-Rak, M.; Awedyk, M. Strategic planning for sustainable tourism development in Poland. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z.; Özer, P.; Ayaz, E. The evaluation of ecology-based tourism potential in coastal villages in accordance with landscape values and user demands: The Bursa Mudanya-Kumyaka case. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S.; Atanur, G. The prioritization of natural-historical based ecotourism strategies with multiple-criteria decision analysis in ancient UNESCO city: Iznik-Bursa case. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardano, S. Agrarian landscapes: From marginal areas to cultural landscapes-paths to sustainable tourism in small villages-the case of Vico Del Gargano in the club of the Borghi più belli d’Italia. Qual. Quant. 2019, 54, 1725–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, M.; Ruiz-Chico, J.; Peña-Sánchez, R. Landscape and Tourism: Evolution of Research Topics. Land 2020, 9, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan Ayhan, Ç.; Cengiz Taşlı, T.; Özkök, F.; Tatlı, H. Land use suitability analysis of rural tourism activities: Yenice, Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmin, F.; Sultan, M.T.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Li, B. Millennial Tourists’ Environmentally Sustainable Behavior Towards a Natural Protected Area: An Integrative Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özgeriş, M.; Karahan, F. Use of geopark resource values for a sustainable tourism: A case study from Turkey (Cittaslow Uzundere). Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4270–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateoc-Sîrb, N.; Albu, S.; Rujescu, C.; Ciolac, R.; Țigan, E.; Brînzan, O.; Mănescu, C.; Mateoc, T.; Milin, I.A. Sustainable Tourism Development in the Protected Areas of Maramures, Romania: Destinations with High Authenticity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipak, B.; Harper, J.; Nepal, S. Sustainable tourism in practice: Synthesizing sustainability assessment of global tourism destinations. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2023, 30, 671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Climate Data. Available online: https://tr.climate-data.org/asya/tuerkiye/bursa/gemlik-9214/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Gemlik Kaymakamlığı. Available online: http://www.gemlik.gov.tr/cografya1 (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Çevre Şehircilik Bakanlığı Çevre Durum Raporu. 2017. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/ced/icerikler/2017_bursa_cdr_son-20180913120048.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Gemlik Belediyesi. Available online: http://gemlik.bel.tr/tr (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Çevre Şehircilik Bakanlığı Bursa Province Integrated Coastal Plan Report. 2015. Available online: https://webdosya.csb.gov.tr/db/ced/editordosya/Bursa2015.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Topay, M. Bartın-Uluyayla Peyzaj Özelliklerinin Rekreasyon-Turizm Kullanımları Açısından Değerlendirilmesi Üzerine bir Araştırma. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benliay, A. Peyzaj Planı Oluşturulması Bağlamında Finike-Kumluca Kıyı Bölgesinin Değerlendirilmesi. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parladır, Ö. Isparta İli’nde Yapılacak Alternative Turizm Türlerinin ve Yerlerinin CBSaraçları ile Belirlenmesi. Master’s Thesis, Süleyman Demirel University, Isparta, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Topay, M.; Parladır, M.Ö. Isparta ili örneğinde CBS yardımıyla alternatif turizm etkinlikleri için uygunluk analizi. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- Baltacı, A. The qualitative research process: How to conduct a qualitative research? Ahi Evran Univ. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2019, 5, 368–388. [Google Scholar]

- Graribvand, I.K.; JAmali, A.A.; Amiri, F. Changes in NO2 and O3 levels due to the pandemic lockdown in the industrial cities of Tehran and Arak, Iran using Sentinel 5P images, Google Earth Engine (GEE) and statistical analysis. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 2023–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kıral, B. Document analysis as a qualitative data analysis method. J. Soc. Sci. Inst. 2020, 8, 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Topay, M. Mapping of thermal comfort for outdoor recreation planning using GIS: The case of Ispar GIS: The case of Isparta Province (Turkey). Turk. J. Agric. For. 2013, 37, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, O. Genel Klimatoloji; Gazi Büro Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, D.B. Multiple range and multiple F tests. Biometrics 1955, 11, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolukan, E. Niğde özel Yetenekle Ilgili Bölümlerde Okuyan Üniversite Öğrencilerinin Rekreasyonel Aktivitelere Katılımlarına engel Olabilecek Unsurların Belirlenmesi. M.Sc. Thesis, Niğde University, Niğde, Turkey, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sabancı, G. Öğretim Elemanlarının Rekreasyonel Faaliyetlere Katılımlarını Engelleyen Faktörlerin Belirlenmesi. M.Sc. Thesis, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 2019, 20, 1305–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.; Polat, A. The evaluation of user preferences: The case of urban parks in Konya. J. Macro Trends Energy Sustain. 2014, 2, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Uyanık, H.S. Yeni kent Kurgusunda Rekreatif Yeşil Alanlar ve Parklar Üzerine Sosyolojik bir Araştırma. M.Sc. Thesis, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sertkaya, Ş. Bartın ili kıyı Bölgesinin Turizm ve Rekreasyon Potansiyelinin Saptanması ve Değerlendirilmesi Üzerine bir Araştırma. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Altan, T. Çukurova’da Bilgisayar Yardımı ile Bölgesel Ölçekte Ekolojik Peyzaj Planlaması Uygulaması ve alan Kullanış Önerisinin Saptanması Üzerinde bir Araştırma. unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Şimşek, D.S.; Korkut, A.B. Kıyı şeridi rekreasyon potansiyelinin belirlenmesinde bir yöntem uygulaması: Tekirdağ merkez ilçe örneği. J. Tekirdag Agric. Fac. 2009, 6, 315–327. [Google Scholar]

- Yaşar, Y.; Düzgüneş, E. Peyzaj tasarımına sürdürülebilirlik kavramının entegrasyonu: Bir stüdyo çalışması. İnönü Univ. J. Art Des. 2013, 3, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Yücedağ, C.; Kaya, L.G.; Çetin, M. Identifying and assessing environmental awareness of hotel and restaurant employees’ attitudes in the Amasra District of Bartin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yener, D.; Güzel, M. Evaluation of Besiktaş Abbasağa park plants in the context of ecological tolerance criteria. In Research in Landscape and Ornamental Plants; Zencirkıran, M., Ed.; Gece Kitabevi: Ankara, Turkey, 2019; pp. 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Düzgüneş, E.; Demirel, Ö. Milli Parkların Koruma Yapısının Ekolojik Duyarlılık Analizi ile Ortaya Konması: Altındere Vadisi Milli Parkı Örneği. Kastamonu Üniversitesi Orman Fakültesi Derg. 2016, 16, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, J.; Dikey, A. Benchmarking Ecotourism in New Zealand: Ac. 1999 Analysis of Activities Offered and Resources Utilised by Ecotourism Businesses. J. Ecotourism 2007, 6, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrosu, G.M.; Balvis, T. Environmental Impact Assessment in Climbing Activities: A New Method to Develop a Sustainable Tourism in Geological and Nature Reserves. Geoheritage 2020, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.; Correia, A.; Rachão, S.; Nunes, A.; Vieira, E.; Santos, S.; Soares, L.; Fonseca, M.; Ferreira, F.A.; Veloso, C.M. A Methodology for the Identification and Assessment of the Conditions for the Practice of Outdoor and Sport Tourism-Related Activities: The Case of Northern Portugal. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonia, A.; Jezierska-Thöle, A. Sustainable Tourism in Cities—Nature Reserves as a ‘New’ City Space for Nature-Based Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuković, M. The Application of GIS in sustainable tourism management. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.; Paul, I.; Sarkar, B. Geotourism site suitability assessment by a novel GIS-based MCDM method in the Eastern Duars region (Himalayan foothill) of West Bengal, India. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavilanes Montoya, A.V.; Esparza Parra, J.F.; Chávez Velásquez, C.R.; Tito Guanuche, P.E.; Parra Vintimilla, G.M.; Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Castillo Vizuete, D.D. A Nature Tourism Route through GIS to Improve the Visibility of the Natural Resources of the Altar Volcano, Sangay National Park, Ecuador. Land 2021, 10, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishant, N.; Sahin, A.; Chutia, D.; Devaraj, R.; Singh, P.S.; Saikhom, V.; Chouhan, A.; Bhuyan, S.; Anilkumar, R.; Aggarwal, S.P. Exploring the Untapped Potential: Using AHP and GIS to Identify Suitable Areas for Tourism Development in Meghalaya. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Stud. 2023, 3, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chandel, R.S.; Kanga, S.; Singh, S.K.; Ðurin, B.; Oršulić, O.B.; Dogančić, D.; Hunt, J.D. Assessing Sustainable Ecotourism Opportunities in Western Rajasthan, India, through Advanced Geospatial Technologies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkey’s Twelfth Development Plan. Available online: https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/On-Ikinci-Kalkinma-Plani_2024-2028_11122023.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s 2024–2028 Strategic Plan. Available online: http://www.sp.gov.tr/upload/xSPStratejikPlan/files/XX9Hs+KTB24-28sp.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z.; Ender Altay, E. Ekolojik Temelli Turizm ve Rekreasyonda Planlama Yaklaşımları, Peyzaj Mimarlığında (Planlama, Tasarım ve Peyzaj Bitkileri) Güncel Çalışmalar; Gece Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; pp. 201–214. [Google Scholar]

| Evaluation Criteria | Tent Camping | Caravan Camping | Hiking | Trekking | Landscape Viewing and Nature Photography | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Suitable | Suitable | Most Suitable | Suitable | Most Suitable | Suitable | Most Suitable | Suitable | Most Suitable | Suitable | |

| Slope % | 0–15 | - | 0–15 | - | 0–8 | 0–12 | 5–20 | 5–30 | - | - |

| Exposition | Straight, E, G, SE, SW, W | N, NE, NW | Straight, E, G, SE, SW, W | N, NE, NW | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Height (m) | 0–326 | - | 0–326 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Geological formations | - | - | - | - | - | - | Few | - | - | - |

| Landslide situation (% slope) | 0–30 | - | 0–30 | - | Few | - | - | - | 45 | - |

| Peaks (m) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 | - |

| Soil Drainage | - | - | - | - | Good | Good-Fair | - | - | - | - |

| Soil Texture | - | - | - | - | Coarse–Medium | Coarse–Medium- Fine | - | - | - | - |

| Proximity to water sources (m) | 0–250 | 250–500 | 50 and over | - | 50–300 | 50–1600 | 50–300 | 50–1600 | 500–1000 | 1000 and over |

| Current land/area use | Forest, Shrubbery, Pasture, Coastal dunes | - | Forest, Shrubbery, Pasture, Coastal dunes | - | Forest, Shrubbery | Forest, Shrubbery, Pasture meadow | Forest, Shrubbery | Forest, Shrubbery, Pasture meadow | Pasture, Forest, Settlement, Beach | - |

| Presence of Vegetation | - | - | - | - | Available | - | Available | - | - | - |

| Natural plant existence | Leafy forest, mixed forest, treeless area | Coniferous forest | Open and semi-open areas | - | - | - | - | - | Deciduous forest, mixed forest, treeless area | Coniferous forest |

| Forest canopy (%) | 0–70 | - | 0–40 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Relative humidity | 30–80 | - | 30–80 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Average wind speed (m/sec) | 0–10 | 10–15 | 0–10 | 10–15 | - | - | - | - | 0–10 | 10–15 |

| Existence of Floodplain | Absence | - | Absence | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Transportation distance (m) | 0–3000 | 3000 and over | 0–100 | - | 0–1000 | 0–3000 | 0–5000 | - | - | - |

| Land ability class | IV, VI, VII, Beach | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Track Length | - | - | - | - | 5000 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Availability of Energy Resources | - | - | - | - | 0–3000 | - | 5000 | - | - | - |

| Presence of Health Facilities | - | - | - | - | 0–3000 | - | 5000 | - | - | - |

| Name of the Wind | Wind (M/S) | Wind (Km/H) | Beaufort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe | 0–1 | 0–4 | 0 |

| Light Breeze | 1–2 | 4–6 | 1 |

| Light Briz | 2–4 | 6–12 | 2 |

| Weak Briz | 4–6 | 12–19 | 3 |

| Moderate Briz | 6–8 | 19–27 | 4 |

| Hard Briz | 8–10 | 27–35 | 5 |

| Strong Wind. | 10–12 | 35–45 | 6 |

| Severe Wind. | 12–15 | 45–55 | 7 |

| Stormy Wind. | 15–18 | 55–66 | 8 |

| Storm | 18–21 | 66–77 | 9 |

| Severe Storm | 21–25 | 77–90 | 10 |

| Orcanoid Fir. | 25–30 | 90–105 | 11 |

| Orkan Hurricane | Above 30 | More than 105 | 12 |

| Optimal Land Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Most Suitable Area (ha) | Suitable Areas (ha) | Intersecting Area (ha) | ||

| Activities | Tent Camping | 100.52 e | 264.65 d | 365.17 e |

| Hiking | 173.79 c | 1790.2 c | 91790.2 d | |

| Trekking | 1747.71 b | 4259.9 b | 4259.9 c | |

| Caravan Camping | 110.04 d | 7984.66 a | 7984.66 a | |

| Landscape Viewing and Nature Photography | 6162.53 a | 264.65 d | 6427.18 b | |

| Significance | ** | ** | ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gürbüz, E.; Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z. Evaluation of Ecologically Based Activities Within the Scope of Sustainable Tourism and Recreation Planning. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052136

Gürbüz E, Pirselimoğlu Batman Z. Evaluation of Ecologically Based Activities Within the Scope of Sustainable Tourism and Recreation Planning. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052136

Chicago/Turabian StyleGürbüz, Ebru, and Zeynep Pirselimoğlu Batman. 2025. "Evaluation of Ecologically Based Activities Within the Scope of Sustainable Tourism and Recreation Planning" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052136

APA StyleGürbüz, E., & Pirselimoğlu Batman, Z. (2025). Evaluation of Ecologically Based Activities Within the Scope of Sustainable Tourism and Recreation Planning. Sustainability, 17(5), 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052136