Sustainable Development of Teamwork at the Organizational Level—Case Study of Slovakia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Team system and work positions in the team.

- Division of tasks in the team and tasks management.

- Team communication (external, internal).

Theoretical Foundations of Sustainable Development of Teamwork

2. Materials and Methods

- The impact of different perspectives on teamwork: The review highlights contrasting views on teamwork, from empowering employees to exerting control. Investigating how these perspectives manifest in practice and their impact on team dynamics is crucial.

- The role of organizational factors: The review emphasizes the significance of factors like team autonomy, communication, and training in shaping team effectiveness. Research is needed to understand how these factors interact and influence team outcomes.

- The sustainability of teamwork: The review acknowledges the dynamic nature of teams and the importance of factors like team cohesiveness and conflict resolution for long-term success. Research should explore how organizations can foster sustainable teamwork over time.

- (a)

- To conduct a questionnaire survey among companies operating in the Slovak Republic (The questionnaire is included as Appendix B);

- (b)

- To conduct qualitative semi-structured interviews with managers who are responsible for managing sustainable development of teamwork at the organizational level;

- (c)

- Based on the results of the surveys, formulate conclusions, and recommendations for practice.

- Team system and work positions in the team. We needed to understand how the teams under study are formed, whether it is a purposeful way given by the management, or whether there is room for more free possibilities of team formation (so called bottom-up).

- Division of tasks in the team and tasks management. As in the previous area, we investigated whether the roles in the team are clearly and firmly prescribed by the management, or whether there is a degree of free or ad hoc adaptation. We also needed to understand the managerial sense of the situations under study.

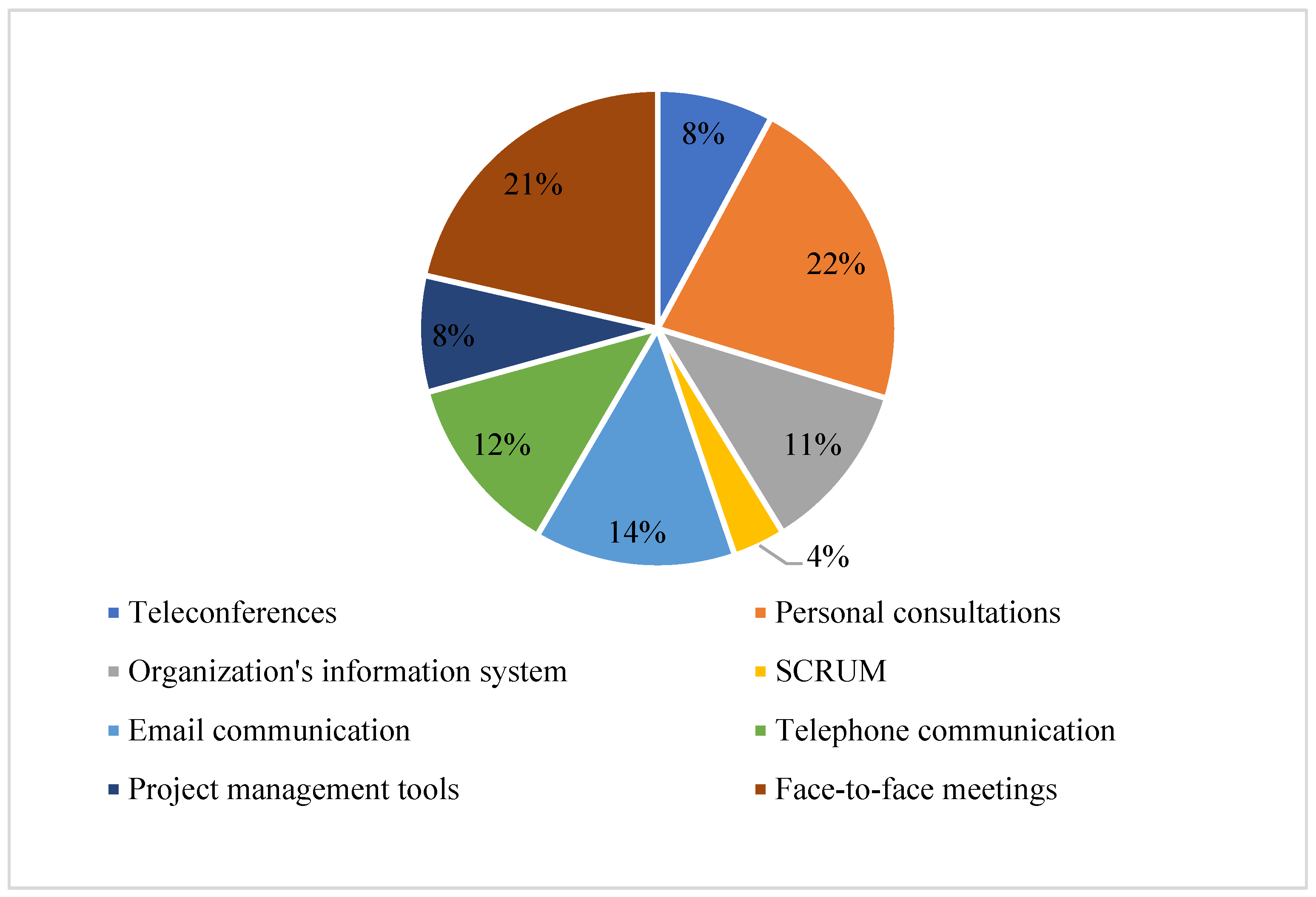

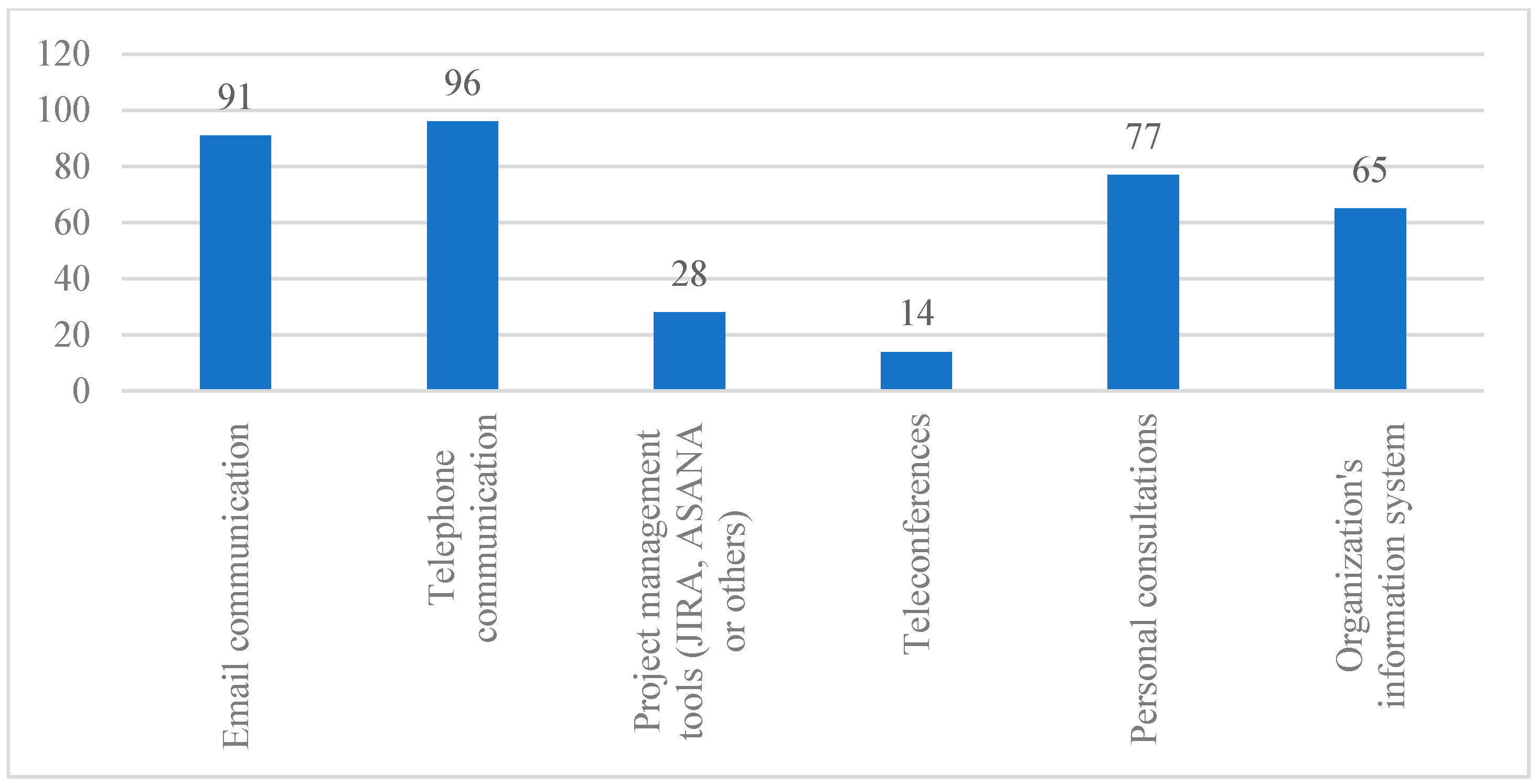

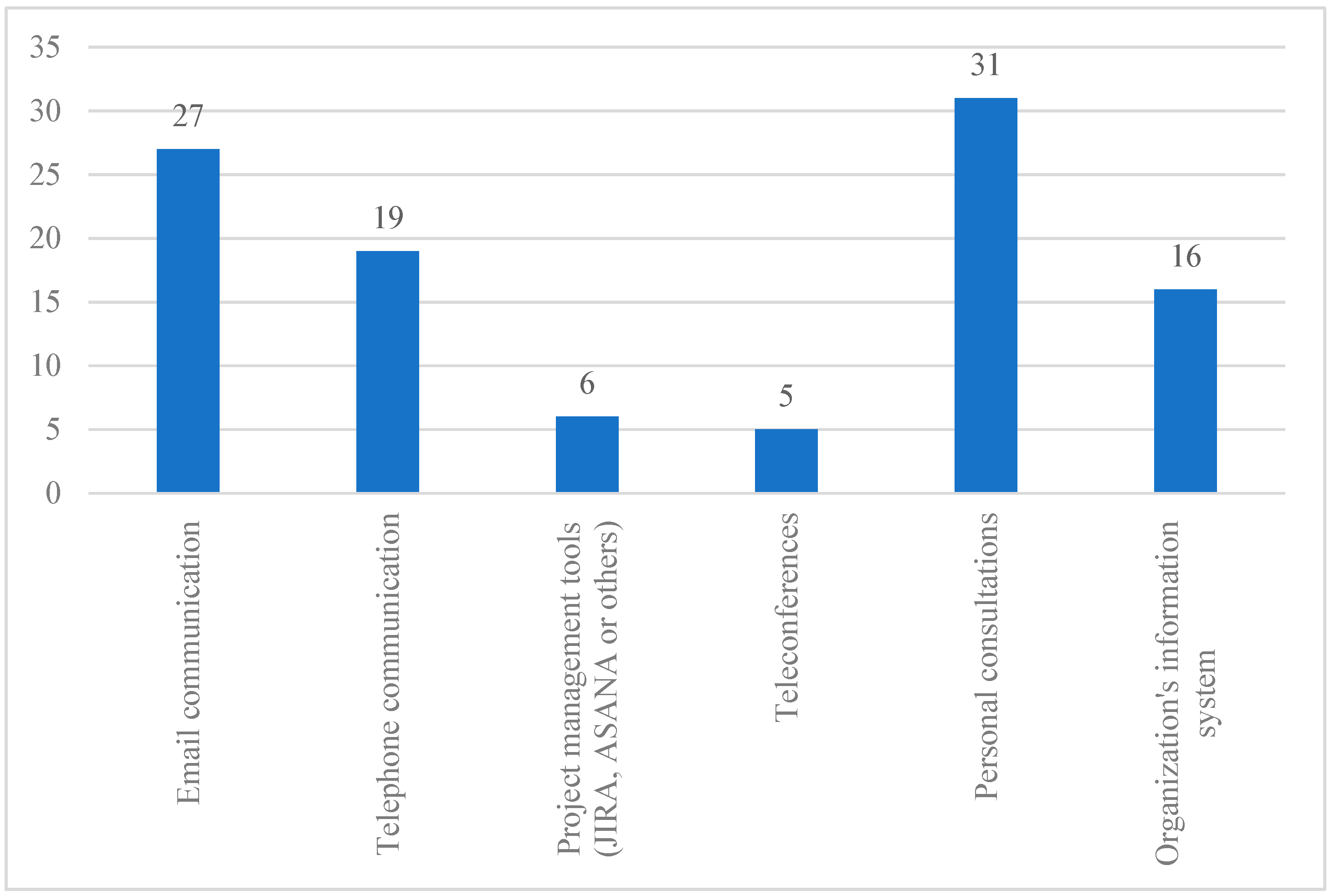

- Team communication (external, internal). We focused on understanding what is used most often and what is considered most effective in the cases studied in terms of communication. Also, the opposite, what is considered to be the least effective. Here, we understood communication mainly from a managerial perspective, specifically in terms of its impact on the achievement of goals and the effectiveness of team functioning.

- Team training activities. In this area, we needed to understand how management works with developing the capabilities of team members. Also, the degree of flexibility in this area, such as the procedures given and the degree of free decision-making choices made by team members.

3. Results

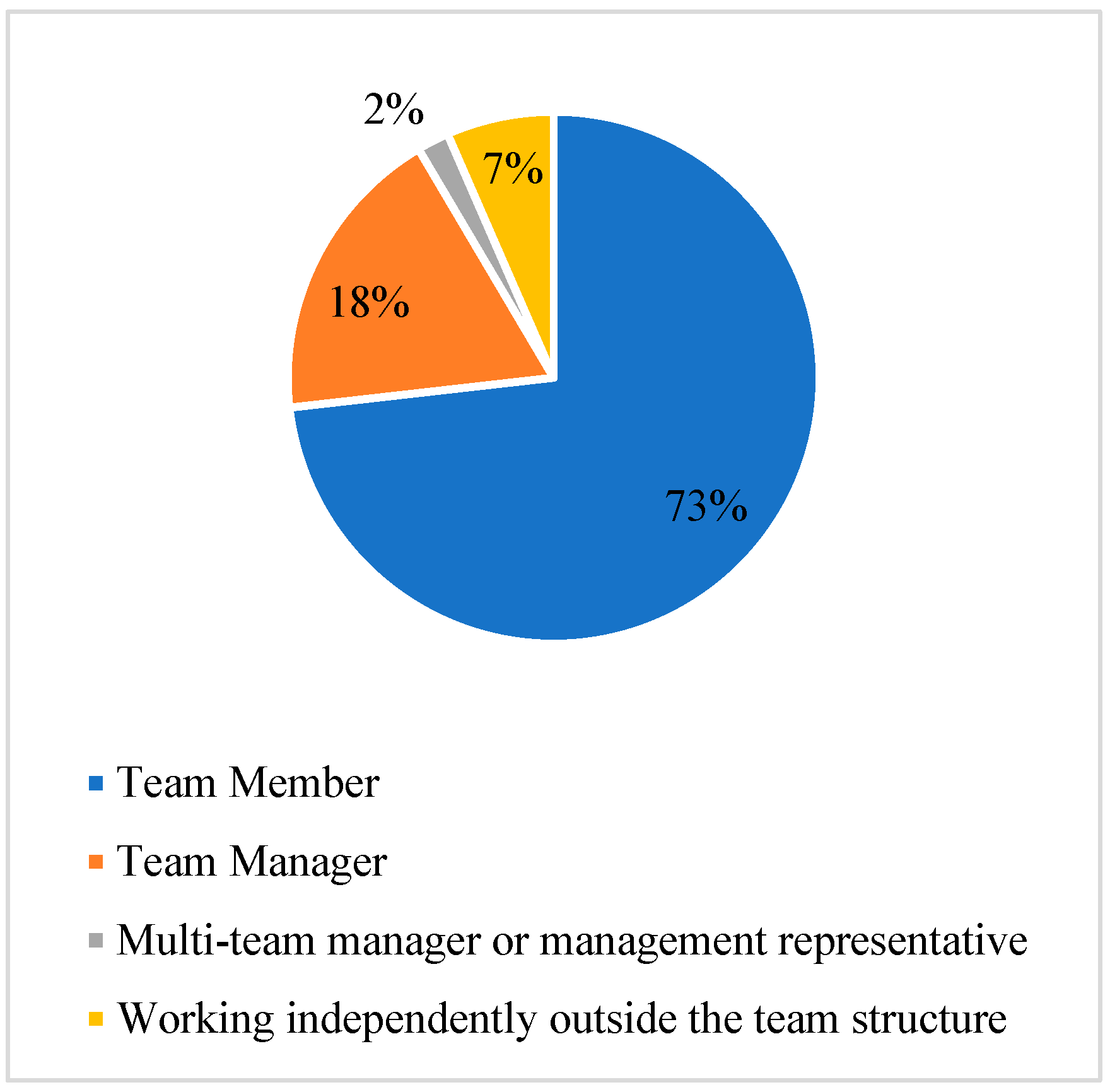

3.1. Team System and Work Positions in the Team

3.2. Division of Tasks in the Team and Tasks Management

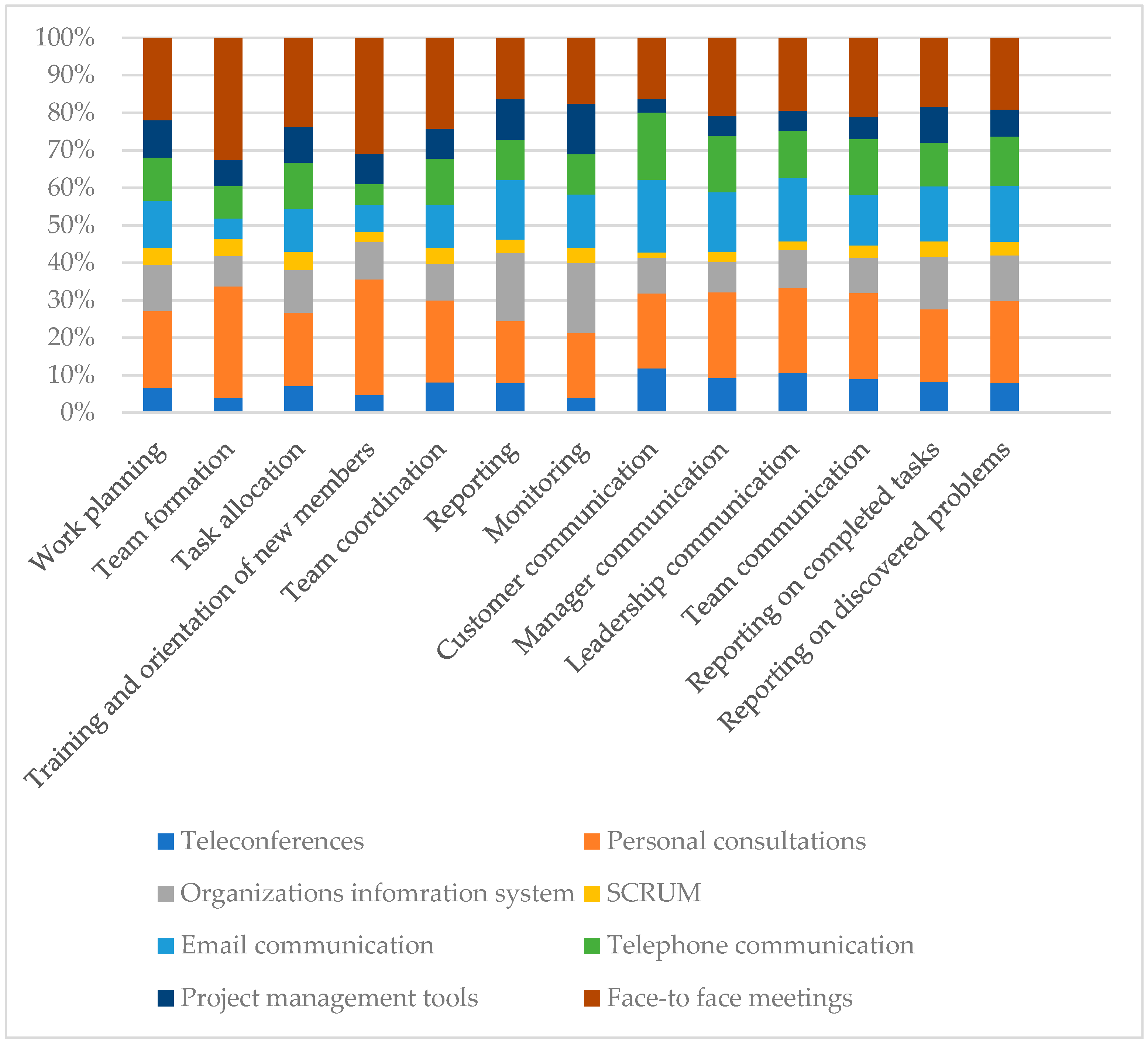

3.3. Team Communication (External, Internal)

- -

- Face-to-face communication emerged as a prominent channel, particularly in activities such as team building and the training and orientation of new team members. These activities often benefit from in-person interaction, fostering stronger interpersonal connections and facilitating knowledge transfer.

- -

- Other activities, such as work planning, task division, and reporting, may be more effectively conducted through ICT-mediated communication tools, allowing for greater flexibility, efficiency, and accessibility.

- (a)

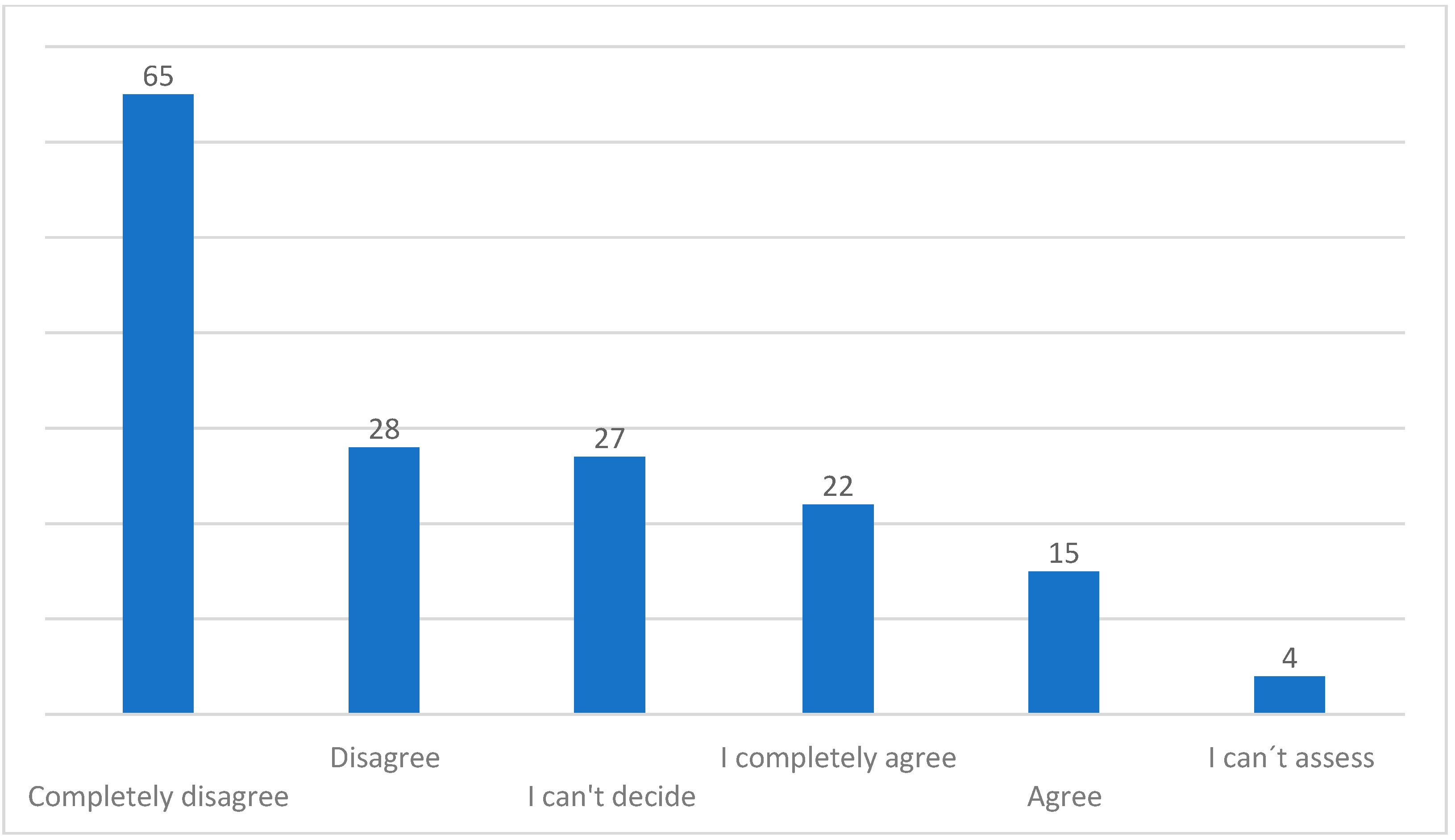

- Unification of ICT tools to enhance transparency and reduce the reliance on time-consuming personal consultations.

- (b)

- Application of agile methodologies for effective project and team management.

- (c)

- Fostering social and professional relationships across departments to facilitate the organic formation of teams.

- (d)

- Investing in comprehensive teamwork education and training programs.

- (e)

- Prioritizing the social aspect of team dynamics and management.

- (f)

- Supporting the development and management of multicultural virtual teams.

- (g)

- Promoting a flatter organizational structure.

3.4. Team Training Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. Team System, Work Positions in the Team, Traditional and Agile Approaches

- Key Differences and Insights:

- Stability vs. Adaptability: Traditional structures prioritize stability and adherence to procedures, while agile structures emphasize adaptability and rapid response to change [48].

- Control vs. Empowerment: Traditional structures focus on control and oversight, while agile structures promote empowerment and team autonomy [49].

4.2. Division of Tasks in the Team, Tasks Management, ICT Implentation Issues, and Remote Work

- Lack of Understanding and Strategic Planning. Many organizations adopt ICT tools without fully grasping their potential benefits or having a clear implementation strategy. This can lead to resistance from employees who view these tools as disruptive or unnecessary, hindering successful integration into workflows.

- Incompatibility Issues. Often, organizations implement ICT tools in a piecemeal fashion, without considering the broader context or existing systems. This can create compatibility problems, negating the potential efficiency gains and leading to wasted time and resources.

- Inadequate Training and Support. Organizations may not provide adequate training and support for employees to effectively utilize new ICT tools. This can result in frustration, low adoption rates, and a perception that these tools are more trouble than they are worth.

- Ignoring Team Culture and Dynamics. ICT implementation often overlooks the importance of team culture and dynamics. Organizations may impose tools without considering team preferences or existing communication norms, leading to resistance and hindering collaboration.

- We see the following as possible solutions for successful ICT implementation: develop a comprehensive ICT strategy. Organizations should develop a comprehensive ICT strategy that aligns with their overall goals and objectives. This strategy should include a thorough assessment of needs, a clear implementation plan, and a focus on compatibility with existing systems.

- Provide Adequate Training and Support. Organizations should invest in training and support to ensure that employees have the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively utilize new ICT tools. This includes providing clear instructions, offering ongoing support, and addressing any technical challenges that may arise.

- Foster a Culture of Collaboration and Open Communication. Organizations should promote a culture of collaboration and open communication, encouraging employees to share their feedback and suggestions regarding ICT implementation. This can help identify potential challenges early on and ensure that the tools are integrated in a way that supports teamwork and communication.

- Choose the Right Tools for the Job. Organizations should carefully evaluate and select ICT tools that are appropriate for their specific needs and context. This includes considering factors such as team size, project complexity, and communication preferences.

- Prioritize User Experience and Integration. Organizations should prioritize user experience and integration when implementing ICT tools, ensuring that the tools are user-friendly and seamlessly integrate with existing workflows. This can help increase adoption rates and minimize disruption to productivity.

- Monitor and Evaluate Effectiveness. Organizations should continuously monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of ICT tools, making adjustments as needed to optimize their use and ensure they are supporting teamwork and communication goals.

- Remote work coordination

4.3. Team Communication (External, Internal) and Main Psychological Factors

4.4. Team Training Solutions

- Needs Assessment: Conduct a thorough needs assessment to identify specific areas where teams and individuals require training and development. This assessment should consider factors such as team composition, project requirements, and organizational goals.

- Tailored Training Programs: Design training programs that are tailored to the specific needs of the teams and individuals involved. This may involve developing customized training modules, incorporating relevant case studies, and providing opportunities for hands-on practice.

- Blended Learning Approach: Utilize a blended learning approach that combines different training methods, such as online modules, in-person workshops, and on-the-job coaching. This can cater to diverse learning styles and preferences, maximizing the effectiveness of the training.

- Focus on Key Skills and Competencies: Prioritize training on key skills and competencies that are essential for effective teamwork, such as communication, collaboration, problem-solving, and conflict resolution.

- Practical Application and Feedback: Incorporate opportunities for practical application and feedback during training, allowing participants to apply their learning in real-world scenarios and receive constructive feedback on their performance.

- Continuous Improvement: Promote a culture of continuous improvement by encouraging teams and individuals to regularly evaluate their teamwork skills and identify areas for further development.

- Leadership Development: Invest in leadership development programs that equip team leaders and managers with the skills and knowledge to effectively lead and manage teams, fostering a positive team climate and promoting collaboration.

- Evaluation and Refinement: Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of training programs and make adjustments as needed to ensure they are meeting the desired objectives and contributing to improved team performance and organizational outcomes.

- Utilize the Comprehensive Training Model of Teamwork Competence (CTMTC) to assess and develop teamwork competence across various dimensions.

- Incorporate team-building activities and workshops to foster trust, communication, and collaboration among team members.

- Provide training on conflict resolution strategies, enabling teams to address disagreements and challenges constructively.

- Offer leadership development programs that focus on developing emotional intelligence, communication skills, and the ability to motivate and inspire teams.

- Utilize ICT tools and digital collaboration platforms to support teamwork training and development, providing access to online resources, facilitating virtual collaboration, and enhancing communication.

- Establish structured mentorship programs: Pair experienced team members with newer members to provide guidance, support, and knowledge transfer. This can help new members integrate more quickly into the team and learn from the experience of their mentors.

- Provide training for mentors: Offer training to mentors on effective mentoring practices, including communication, feedback, and support techniques.

- Incorporate mentorship into performance evaluations: Include mentorship participation and effectiveness as part of performance evaluations for both mentors and mentees.

- Encourage peer-to-peer mentoring: Foster a culture of peer-to-peer mentoring, where team members can learn from and support each other.

- Incorporate game mechanics into training: Use game mechanics such as points, badges, and leaderboards to motivate and engage participants in training activities.

- Create challenges and simulations: Design training challenges and simulations that mimic real-world teamwork scenarios, allowing participants to practice their skills in a safe and engaging environment.

- Provide rewards and recognition: Offer rewards and recognition for successful completion of training challenges and achievements, reinforcing positive behaviors and motivating continued learning.

- Use gamification to track progress and provide feedback: Utilize gamification elements to track individual and team progress during training, providing real-time feedback and encouraging continuous improvement.

4.5. Brief Comparison with Other Research

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Teamwork is prevalent: A high proportion of tasks are performed by teams, and many employees work within teams.

- Traditional management dominates: Team formation often prioritizes capacity over skills, and management often controls team systems.

- Communication relies heavily on traditional methods: Face-to-face meetings and phone calls are common, while the use of project management tools is limited.

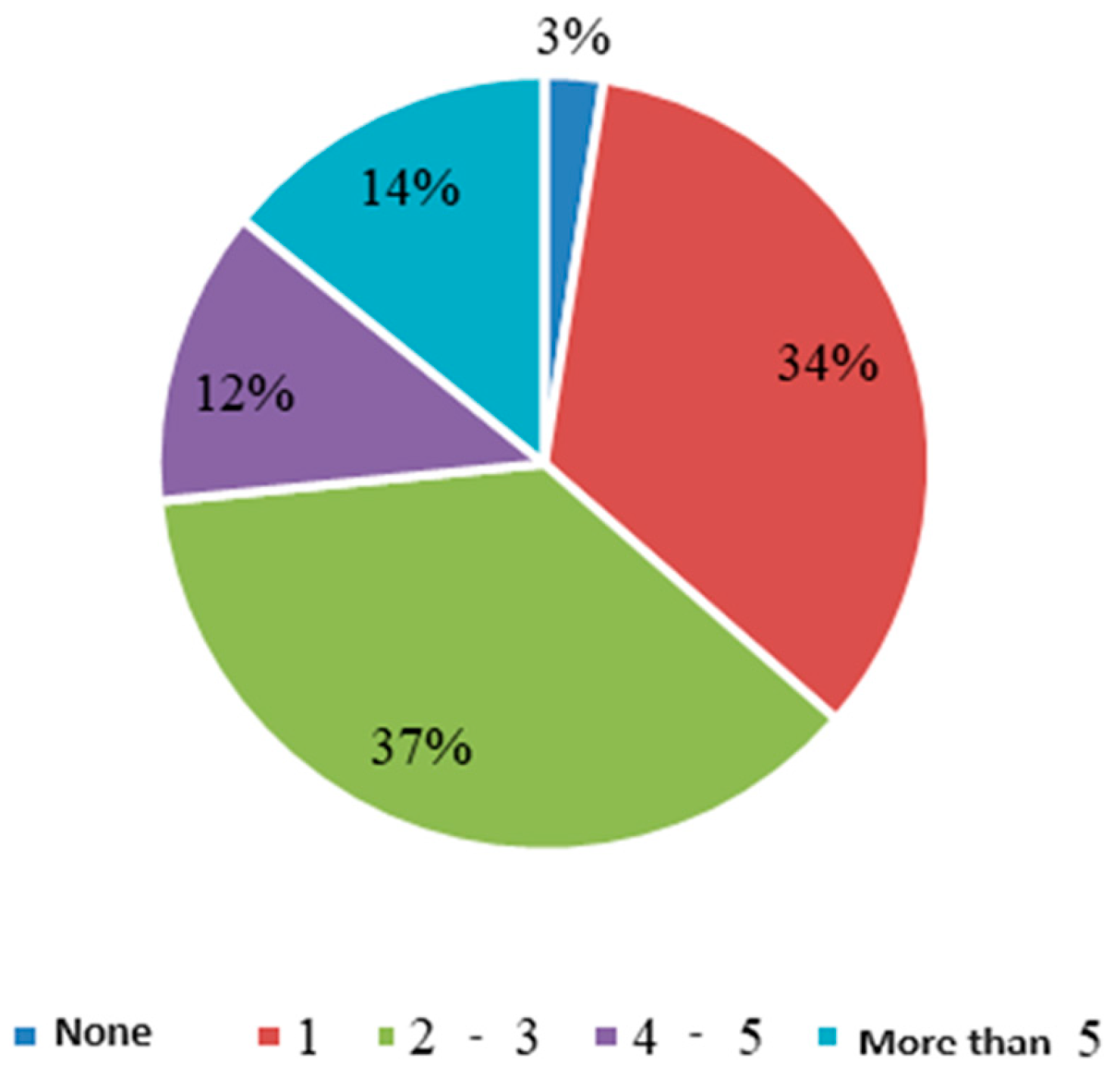

- Training is often lacking: Many employees have not received recent teamwork training, and organizational support for team development is inconsistent.

- Internal competition among teams is discouraged: Organizations generally prioritize cooperation over competition between teams.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The proportion of tasks within an organization that are performed by a team.

- The degree of autonomy of employees.

- The proportion of employees in the organization working individually and in teams.

- The number of teams within a given organizational unit.

- Managers’ preferences for solving tasks using teamwork.

- Does the organization encourage its employees to solve tasks using teamwork and form teams organically?

- How does it create such conditions?

- The proportion of teams formed independently, and teams formed by management.

- Does the organization address the issue of the right balance of teams?

- Are the positions of each member clearly defined at the outset?

- The number of teams within the organization that have a team charter or a document based on similar principle.

- Number of training sessions and workshops on teamwork and interpersonal skills.

- Number of teams per manager.

- Does the organization use a generally accepted team or project management methodology?

- Attributes of teamwork where the methodology is used.

- Level of member satisfaction with the methodology.

- Degree of involvement of ICT in the management and operation of teams.

- Number of systems used by members in teamwork.

- Number of attributes of teamwork in which members use ICT.

- Frequency of progress reports from individual members.

- Frequency of reports on team progress.

- Number of team meetings per specified period.

- The number of progress checks over a specified period.

- The extent to which the manager monitors the use of resources to achieve team goals.

- The average length of time the team has been in operation.

- The turnover of members during team collaboration.

- Does the organization encourage competition among teams?

- The extent and content of information shared within teams.

- Frequency of communication between team members.

- Form of communication (email, ICT, face-to-face meetings).

- Length of time if individual members are assigned to a new team.

- Does the organization have a generally applied tool to evaluate the work of the team?

Appendix B

- Does your organization use teamwork?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

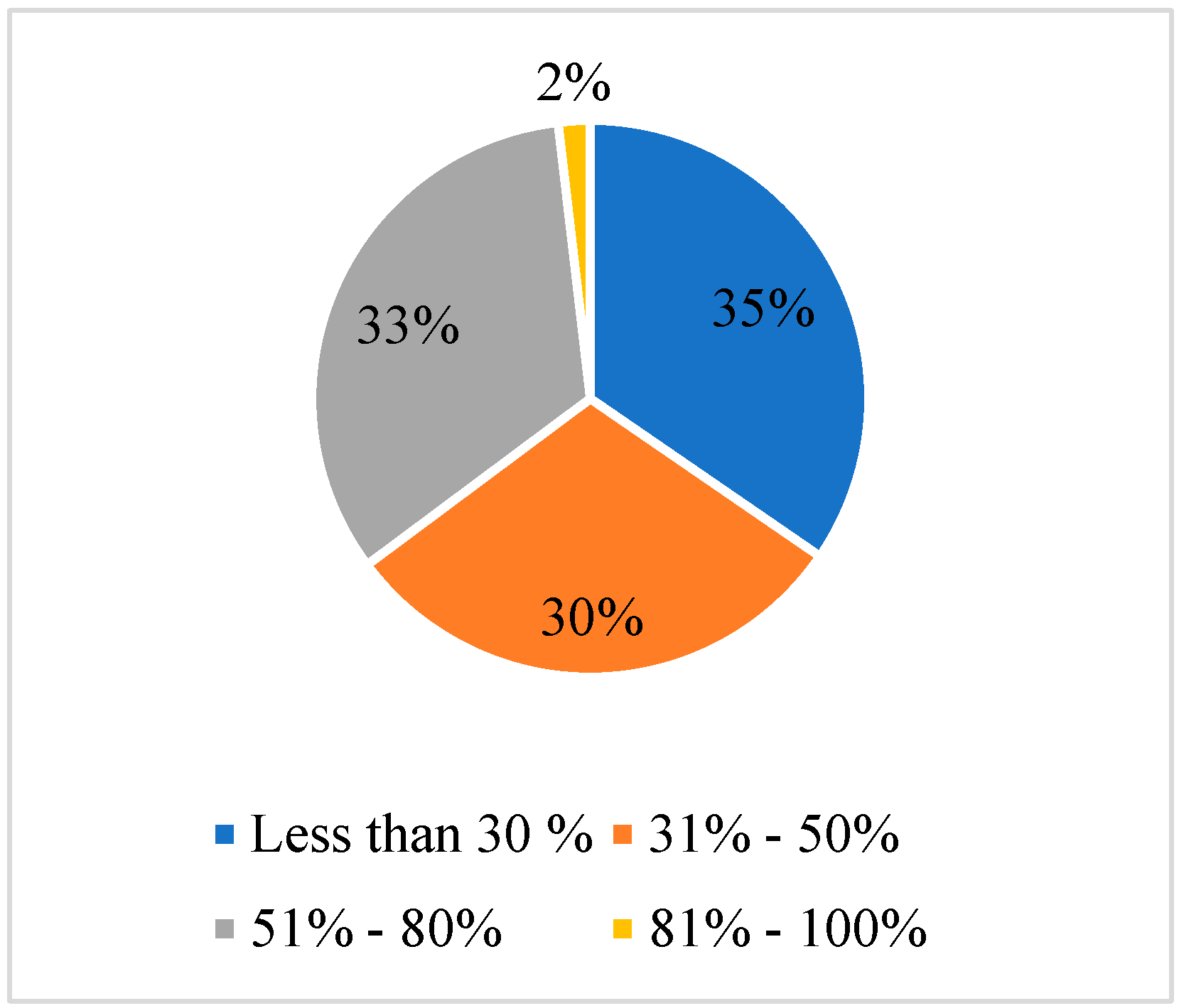

- What percentage of employees in your organization work in teams rather than individually?

- -

- Less than 30%

- -

- 31% to 50%

- -

- 51% to 80%

- -

- 81% to 100%

- How much time do you spend working independently without contact with other team members or your manager?

- -

- Less than 30%

- -

- 31% to 50%

- -

- 51% to 80%

- -

- 81% to 100%

- How many teams in the organization have been purposefully created by management?

- -

- Less than 30%

- -

- 31% to 50%

- -

- 51% to 80%

- -

- 81% to 100%

- What is the number of teams operating within your organization?

- -

- None

- -

- Less than 3

- -

- 3–5

- -

- More than 5

- How many teams fall under 1 manager in your organization?

- -

- None

- -

- 1

- -

- 2–3

- -

- 3–5

- -

- More than 5

- How many training courses or workshops on teamwork have you attended in the last 2 years?

- -

- None

- -

- 1–2

- -

- 3–5

- -

- More than 5

- Do employees in your organization work simultaneously in several teams?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- Please indicate the average number of teams in which an employee of your organization works simultaneously:

- -

- 1

- -

- 2–3

- -

- 4–5

- -

- 6–7

- -

- 8 or more

- Please indicate the number of teams in which you work simultaneously:

- -

- 1

- -

- 2–3

- -

- 4–5

- -

- 6–7

- -

- 8 or more

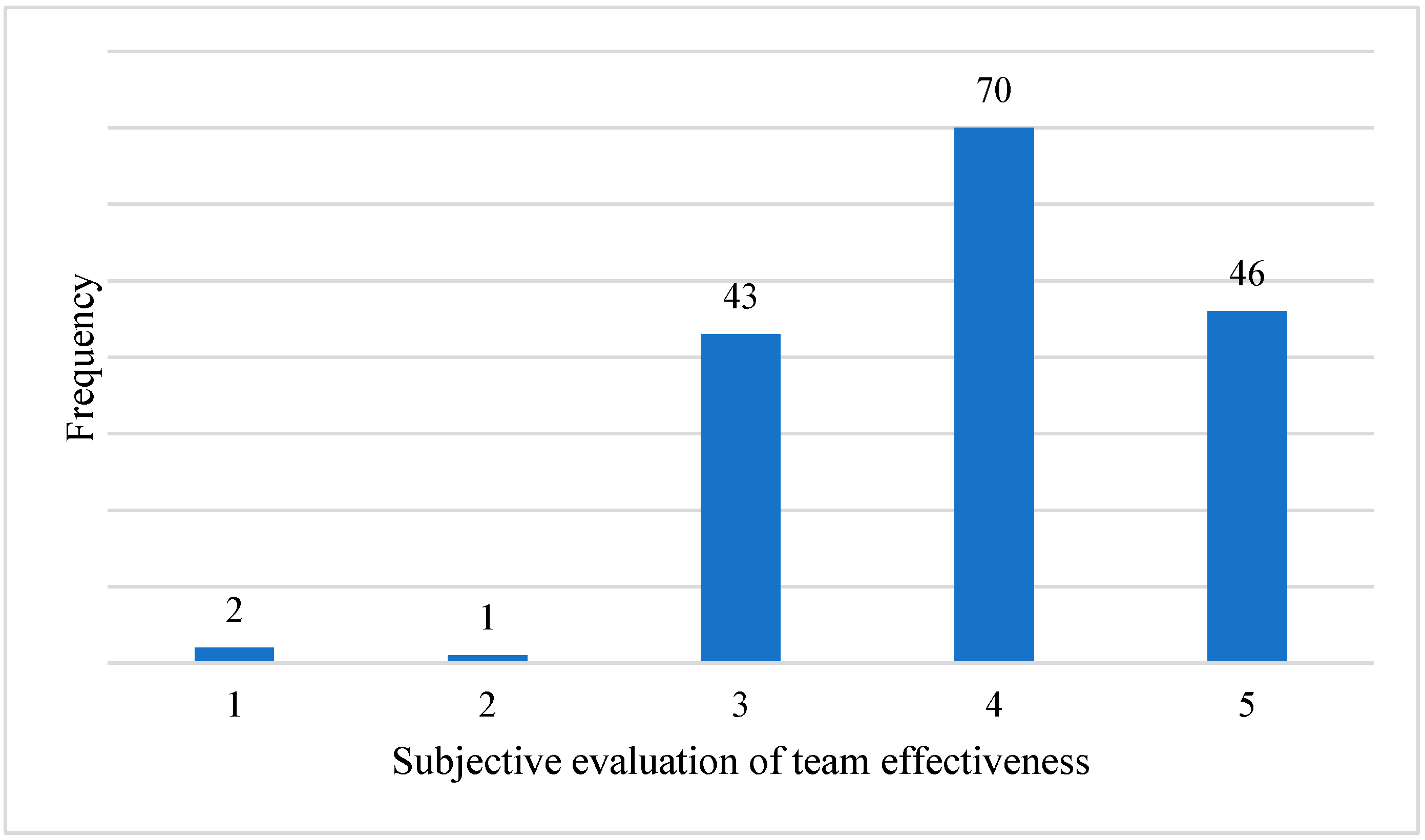

- On a scale of 1 to 5, please rate how effective you think cooperation within your team(s) is.Very inefficient: 1–Very efficient: 5

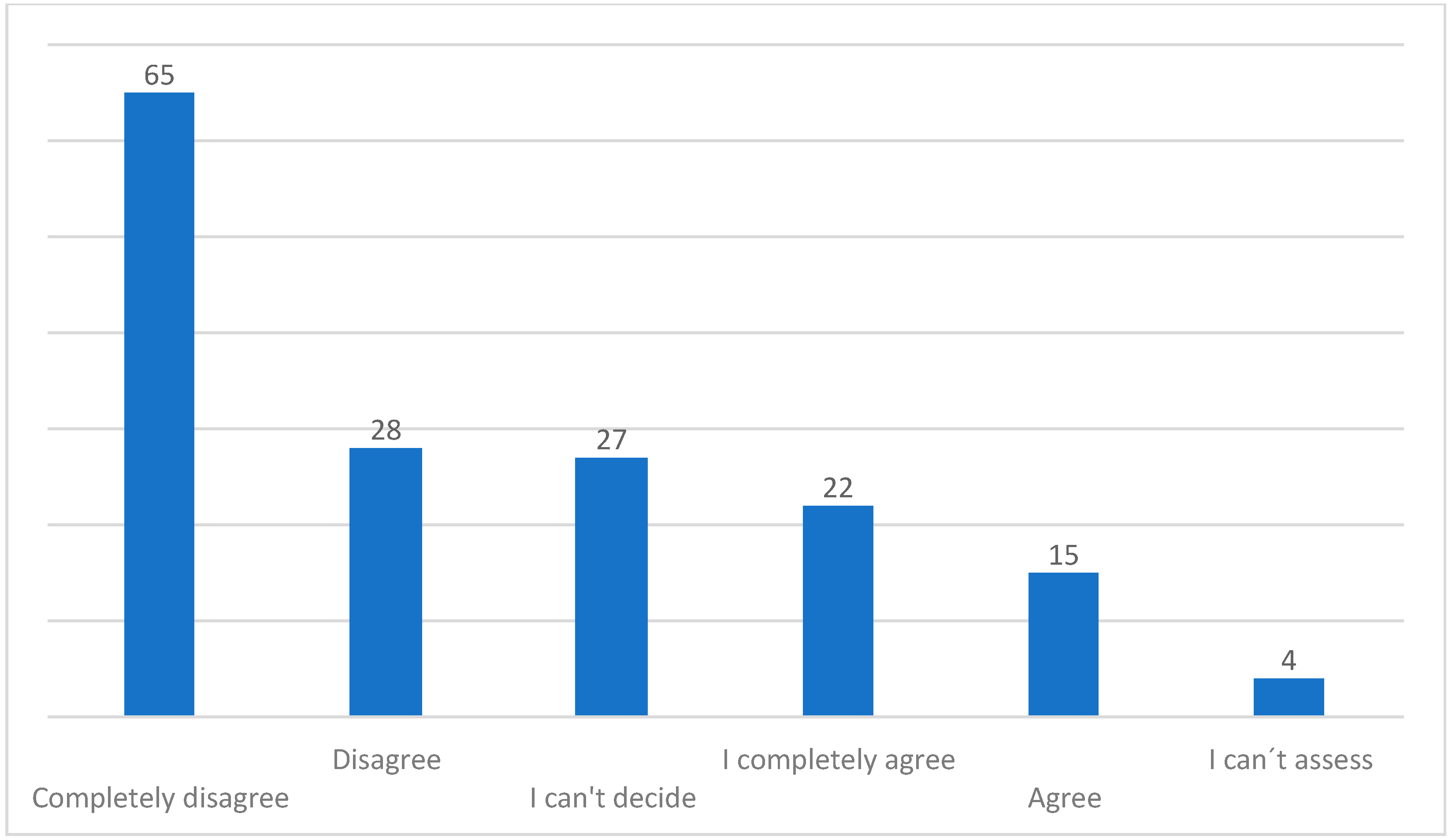

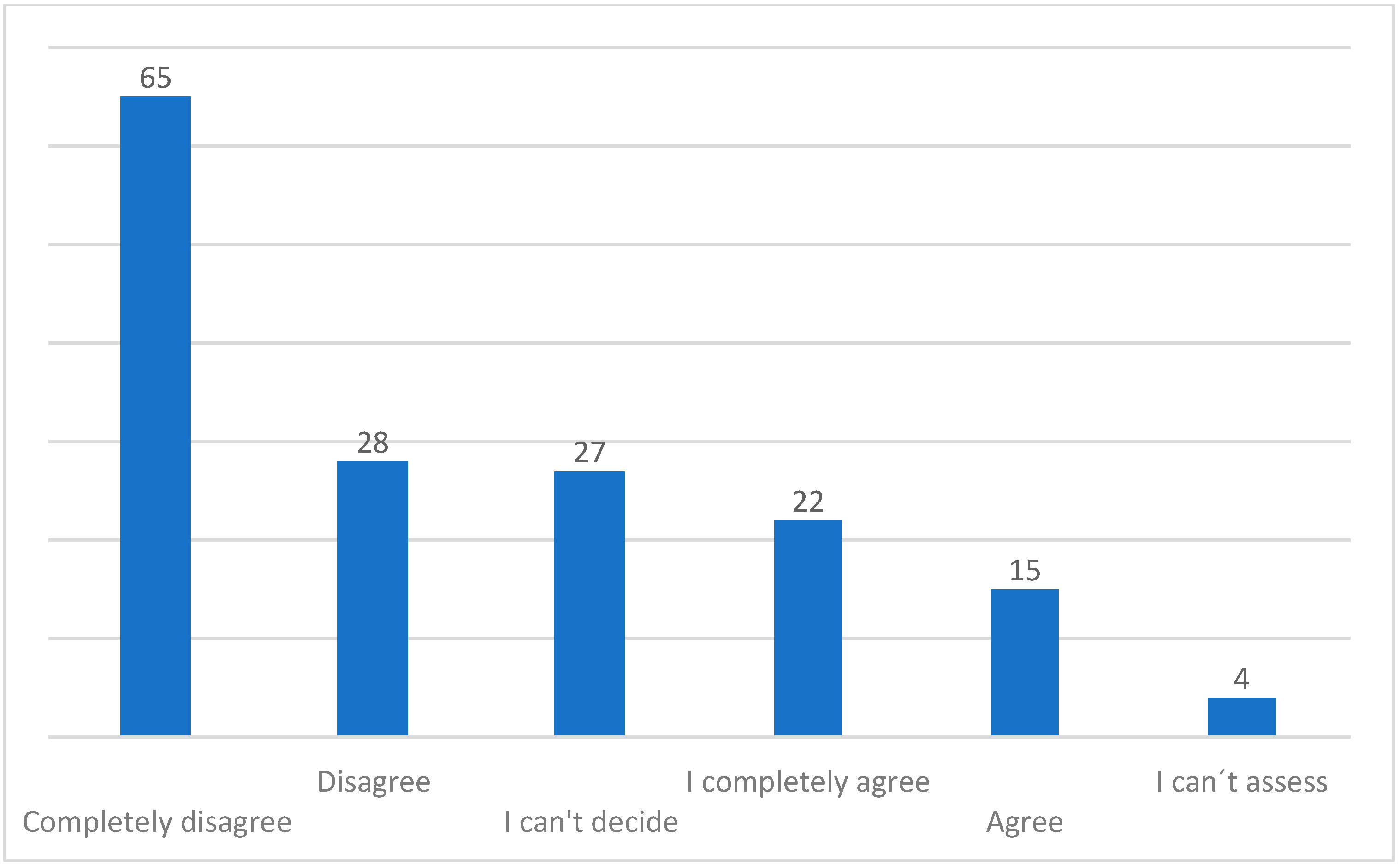

- Please agree with the following statements.(scale from “I completely disagree” to “I completely agree” and “I can’t judge”)

- -

- In our organization, we try to solve tasks and problems mainly as a team.

- -

- The composition of the team is mainly made up of the manager or management.

- -

- The organization leaves the composition of the team to the employees themselves.

- -

- In a team, I am always clear what the goal of the team is.

- -

- In a team, I am always clear what my roles and responsibilities are.

- -

- I was assigned to the team based on my personality traits.

- -

- When working in a team, we follow the principles of management methodology (e.g., SCRUM).

- -

- At the beginning of the team, we wrote down clear rules, members’ competencies and the desired goal.

- -

- My organization creates competitiveness among the teams.

- Indicate for which activities you use which tool.Activities:

- -

- Work planning

- -

- Forming teams

- -

- Task allocation

- -

- Training and orientation of new members

- -

- Team coordination

- -

- Reporting

- -

- Monitoring

- -

- Communication with the customer

- -

- Communication with manager

- -

- Communication with management

- -

- Communication with other team members

- -

- Reporting on completed tasks

- -

- Reporting on problems discovered

Tools:- -

- Teleconferencing

- -

- Personal consultation

- -

- The organization’s information system

- -

- Scrum

- -

- Telephone communication

- -

- Project management tools

- -

- In-person meetings

- -

- Email communication

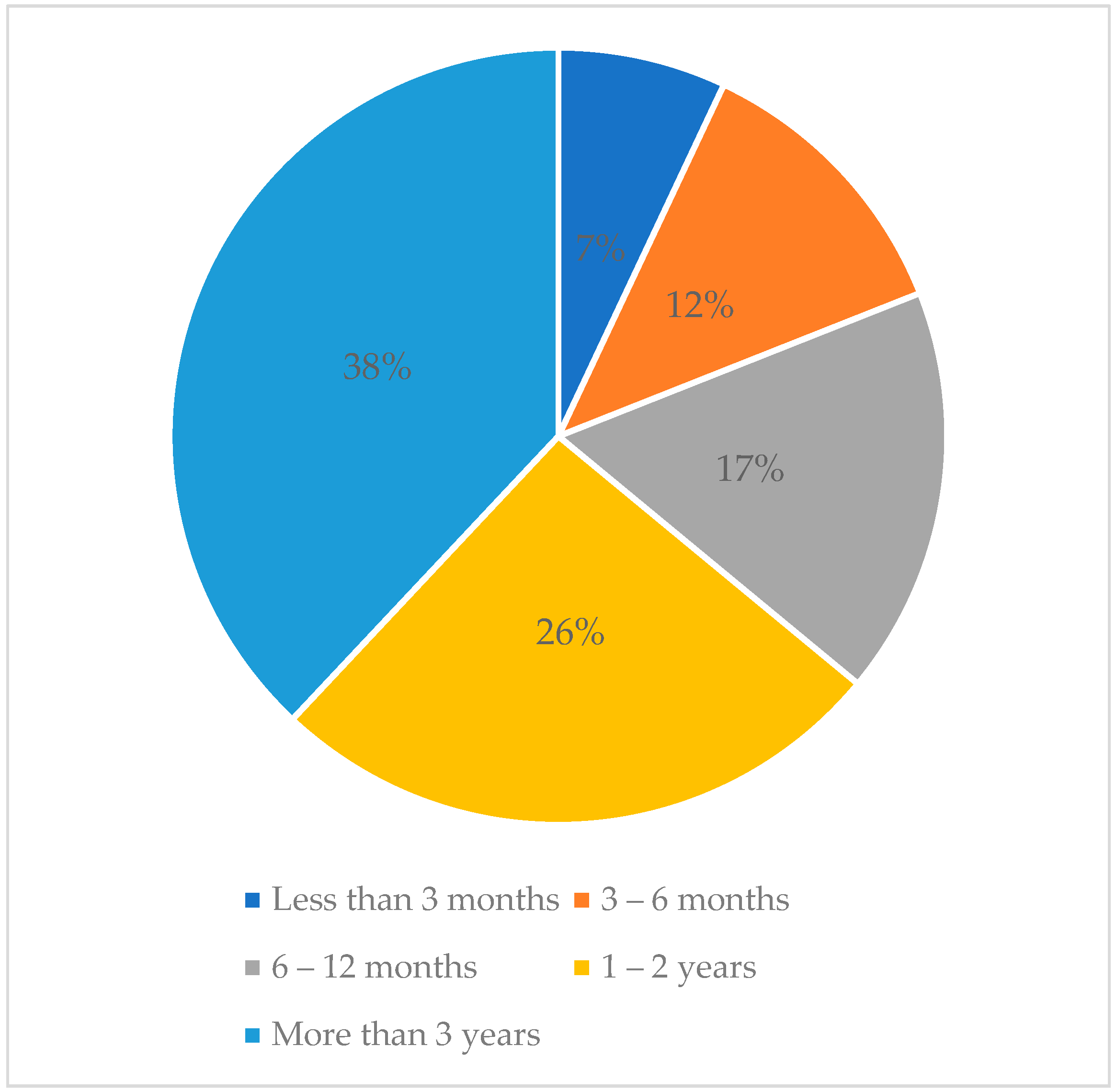

- Please define the average length of time a team has been in your organization.

- -

- Less than 3 months

- -

- 3–6 months

- -

- 6–12 months

- -

- 1–3 years

- -

- More than 3 years

- Please indicate how often you use these communication tools.Communication tools:

- -

- Email communication

- -

- Telephone communication

- -

- Project management tools (Jira, Asana or other)

- -

- Teleconferencing

- -

- Personal consultation

- -

- The organization’s information system

How often- -

- Never

- -

- Less than once a month

- -

- Once a month

- -

- Several times a month

- -

- Once a week

- -

- Several times a week

- -

- Once a day

- -

- Several times a day

- Indicate how much time you spend on average per week using these communication toolsCommunication tools:

- -

- Email communication

- -

- Telephone communication

- -

- Project management tools (Jira, Asana or other)

- -

- Teleconferencing

- -

- Personal consultation

- -

- The organization’s information system

Time spends:- -

- No time at all

- -

- Less than a minute

- -

- A minute

- -

- Several minutes

- -

- An hour

- -

- 1–10 h

- -

- More than 10 h

- Number of employees in your organization

- -

- 1–9

- -

- 10–49

- -

- 50–249

- -

- 250 and more

- Please indicate in which sector your organization is operating:

- -

- Information Technology

- -

- Electrical Engineering

- -

- Construction

- -

- Education, research and development

- -

- Industry

- -

- Transport

- -

- Healthcare

- -

- Other

- Period of existence of the organization:

- -

- Less than 1 year

- -

- 1–3 years

- -

- 4–5 years

- -

- More than 5 years

- Your main position within the organization:

- -

- Team Member

- -

- Team Manager

- -

- Multi-team manager or management representative

- -

- Working independently outside the team structure

- Legal form of your organization:

- -

- Joint stock company

- -

- Limited liability company

- -

- State or public enterprise, institution (including schools and offices)

- -

- Trade

- -

- Public trading company

- -

- Limited partnership

- -

- Cooperative

References

- Salas, E.; Reyes, D.L.; McDaniel, S.H. The science of teamwork: Progress, reflections, and the road ahead. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.P.; Day, R.; Salas, E. Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv. Res. 2006, 41, 1576–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minsen, H. Challenges of teamwork in production: Demands of communication. Organ. Stud. 2006, 27, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Huamán, H.I.; Medina-Valderrama, C.J.; Valencia-Arias, A.; Vasquez-Coronado, M.H.; Valencia, J.; Delgado-Caramutti, J. Organizational Culture and Teamwork: A Bibliometric Perspective on Public and Private Organizations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyshev, P.; Darinskaia, L.; Molodtsova, G.; Oskina, A. Organizing Students’ Online Teamwork for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Online Pedagog. Course Des. 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrissey, M.; Novikov, Z. Joint problem-solving orientation, mutual value recognition, and performance in fluid teamwork environments. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1288904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.J.; LeRoux, D.B.; Parry, D.A.; Watson, B.W. Gamification to Increase Undergraduate Students’ Teamwork Skills. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 1664, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, L.X.; Zhao, R.; Wei, Y.S. How does differential leadership affect team decision-making effectiveness? The role of thriving at work and cooperative goal perception. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 18, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Saavedra, M.; Vallejos, M.; Huancahuire-Vega, S.; Morales-García, C.; Geraldo-Campos, L.A. Work Team Effectiveness: Importance of Organizational Culture, Work Climate, Leadership, Creative Synergy, and Emotional Intelligence in University Employees. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, M.; Payne, J.C.; Kennedy, E. Working better together? empowerment, panopticon and conflict approaches to teamwork. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2014, 35, 483–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F.Y.A.; Amos-Abanyie, S.; Kwofie, T.E.; Amponsah-Kwatiah, K.; Afranie, I.; Aigbavboa, C.O. Contribution of person-team fit parameters to teamwork effectiveness in construction project teams. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2022, 15, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.A.; Arroyabe, M.F.; Ubierna, F.; Arranz, C.F.A.; de Arroyabe, J.C.F. The formation of self-management teams in higher education institutions. Satisfaction and effectiveness. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht-Deobald, U.; Lam, C.F.; Bruch, H.; Kunze, F.; Wu, W. Team boundary work and team workload demands: Their interactive effect on team vigor and team effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D.R. Recent Advances in the Study of Group Cohesion. Group Dyn.-Theory Res. Pract. 2021, 25, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardno, C.; Tetzlaff, K. Tracing the stages of senior leadership team development in new zealand primary schools: Insights and issues. Malays. Online J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 5, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Elms, A.K.; Gill, H.; Gonzalez-Morales, M.G. Confidence Is Key: Collective Efficacy, Team Processes, and Team Effectiveness. Small Group Res. 2022, 54, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, W.P.; Hu, X.X.; Kenneally, C.; Wei, F. Do They See a Half-Full Water Cooler? Relationships Among Group Optimism Composition, Group Performance, and Cohesion. J. Pers. Psychol. 2021, 20, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman, B.; Jensen, M.A. Stages of small-group development revisited. Group Facil. A Res. Appl. J. 2010, 10, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Lu, S.W.; Wu, Z.M.; Deng, Y.Q. Research on the influence of team psychological capital on team members’ work performance. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1072158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzis, A.; Hallo, L. The Experiences and Views of Employees on Hybrid Ways of Working. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berraies, S.; Chouiref, A. Exploring the effect of team climate on knowledge management in teams through team work engagement: Evidence from knowledge-intensive firms. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022, 27, 842–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koman, G.; Bubeliny, O.; Tumova, D.; Jankal, R. Sustainable transport within the context of smart cities in the Slovak republic. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2022, 10, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcover, C.M.; Rico, R.; West, M. Struggling to Fix Teams in Real Work Settings: A Challenge Assessment and an Intervention Toolbox. Span. J. Psychol. 2021, 24, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrício, L.; Franco, M. A Systematic Literature Review about Team Diversity and Team Performance: Future Lines of Investigation. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Hollenbeck, J.; Barnes, C.; Sleesman, D.; Ilgen, D. Coordinated action in multiteam systems. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmus, M.; Kubina, M.; Bosko, P.; Miciak, M. Application of the Perceived Popularity of Sports to Support the Sustainable Management of Sports Organizations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varmus, M.; Bosko, P.; Adámik, R.; Greguska, I. Sports Management In The Context Of Sustainability. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2024, 12, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffenová, N.; Kucharcíková, A. Digitalization in the Human Capital Management. Systems 2023, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disman, M. How Sociological Knowledge Is Produced; Karolinum: Praha, Czech Republic, 2008; p. 372. ISBN 978-80-246-0139. [Google Scholar]

- SUSR. Economic Subjects According to Selected Legal Forms and Category of Number of Employees. Available online: https://datacube.statistics.sk/#!/view/sk/VBD_SK_WIN/og1007rs/v_og1007rs_00_00_00_sk (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Sundstrom, E.; Demeuse, K.P.; Futrell, D. Work teams: Applications and effectiveness. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J.R. Groups That Work (and Those That Don’t): Creating Conditions for Effective Teamwork; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R. Leading Teams; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, C.S.; Stagl, K.C.; Klein, C.; Goodwin, G.F.; Salas, E.; Halpin, S.M. What type of leadership behaviors are functional in teams? A meta-analysis. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, L. Digital Transformation, 7 Types of Organizational Structures +Examples. Whatfix Blog. Available online: https://whatfix.com/blog/organizational-structure/#:~:text=Centralized%20organizational%20structures%20have%20a,a%20straightforward%20chain%20of%20command (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Minnaar, J. 5 Best Practices To Distribute Decision-Making. Corporate Rebels. Available online: https://www.corporate-rebels.com/blog/distribute-decision-making (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Vaia. Formal Organizational Structure. Available online: https://www.vaia.com/en-us/explanations/engineering/professional-engineering/formal-organizational-structure/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Available online: https://www.orgvue.com/resources/articles/an-organisation-is-a-system/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Lucid. Agile Self-Organizing Teams: What They Are and Why They Work. Available online: https://lucidspark.com/blog/agile-self-organizing-teams#:~:text=Rather%20than%20relying%20on%20a,as%20a%20group%20to%20drive (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Koort, K. The Power of 3p-s in Leading Successful Teams. Social Hire. Available online: https://www.social-hire.com/blog/candidate/the-power-of-3p-s-in-leading-successful-teams/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Nieto-Rodriguez, A. ANR #121: Differences in Digital and Traditional Project Management. Available online: https://antonionietorodriguez.com/digital-project-management/ (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Tempo Team. Three Ways to Enable Collaboration Across Agile Teams. Available online: https://www.tempo.io/blog/three-ways-to-enable-collaboration-across-agile-teams (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- I Kennedyd, S.; Zadeh, A.A.; Choi, J.; Alborz, S. Agile Practices and IT Development Team Well-Being: Unveiling the Path to Successful Project Delivery. Eng. Manag. J. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, C. About Self-Organizing Teams. Scrum.org. Available online: https://www.scrum.org/resources/blog/about-self-organizing-teams (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Kobushko, I.; Kobushko, I.; Starinskyi, M.; Zavalna, Z. Managing Team Effectiveness Based on Key Performance Indicators of Its Members. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2020, 14, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.F.; Dailey, S.L. Formal Communication. 2017. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314712165_Formal_Communication (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- PPP: Progress, Plans, Problems. WeekDone. Available online: https://weekdone.com/resources/plans-progress-problems (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Schiel, J. Agile Teams Changing the Game How Self-Managing Teams Are Revolutionizing the Workplace. ScrumAlliance. Available online: https://resources.scrumalliance.org/Article/changing-game (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Zhezherau, A. Building an Agile Team Structure. Wrike. Available online: https://www.wrike.com/agile-guide/agile-team-structures/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Bilderback, S.; Kilpatrick, M.D. Global perspectives on redefining workplace presence: The impact of remote work on organizational culture. J. Ethics Entrep. Technol. 2024, 4, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M. Zapier CEO, Wade Foster, on Building a Strong Remote Company Culture. Medium. 2018. Available online: https://medium.com/smells-like-team-spirit/zapier-ceo-wade-foster-on-building-company-culture-remotely-6a342a0b391c (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Culture Partners. Understanding Hybrid Remote Work: Blending Environments. 2024. Available online: https://culturepartners.com/insights/understanding-hybrid-remote-work-blending-environments/#:~:text=This%20flexibility%20allows%20individuals%20to,of%20their%20home%20office%20or (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Holeiciuc, A.M. A CIO’s Guide to Crafting a Robust Hybrid Work IT Infrastructure. Yarooms. 2024. Available online: https://www.yarooms.com/blog/a-cios-guide-to-crafting-a-robust-hybrid-work-it-infrastructure (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Haiilo. What Is Virtual Communication (+ 6 Best Practices). 2023. Available online: https://blog.haiilo.com/blog/virtual-communication/#:~:text=Today%2C%20there%20are%20plenty%20of,messaging%20solutions%2C%20or%20using%20other (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Wong, S.I.; Zhang, L.M.; Cerne, M.; Moe, N.B. Influence of Digital Communication Configuration in Virtual Teams: A Faultline Perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2024, 41, 1111–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, S.W.J.; Ilgen, D.R. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2006, 7, 77–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gully, S.M.; Incalcaterra, K.A.; Joshi, A.; Beubien, J.M. A meta-analysis of team-efficacy, potency, and performance: Interdependence and level of analysis as moderators of observed relationships. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.; Durham, C.C.; Locke, E.A. The relationship of team goals, incentives, and efficacy to strategic risk, tactical implementation, and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Hernández, O.; Tristán, J.; López-Walle, J.M.; García-Mas, A. Team Dynamics Perceptions, Motivation, and Anxiety in University Athletes. Sustainability 2021, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C.K.W.; Weingart, L.R. Task versus relationship conflict: Team performance, and team member satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geister, S.; Konradt, U.; Hertel, G. Effects of process feedback on motivation, satisfaction, and performance in virtual teams. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Hollenbeck, J.R.; Humphrey, S.E.; Ilgen, D.R.; Jundt, D.; Meyer, C.J. Cutthroat cooperation: Asymmetrical adaptation to changes in team reward structures. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Sivatheerthan, T.; Mntze-Niewöhner, S.; Nitsch, V. Sharing leadership behaviors in virtual teams: Effects of shared leadership behaviors on team member satisfaction and productivity. Team Perform. Manag. 2023, 29, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, M.; Angelmar, R.; Mehra, A. Top management-team diversity and firm performance: Examining the role of cognitions. Organ. Sci. 2000, 11, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P. Preventing and Managing Team Conflict. Harvard Division of Continuing Education. Available online: https://professional.dce.harvard.edu/blog/preventing-and-managing-team-conflict/#:~:text=A%20skillful%20manager%20with%20good,all%20team%20members%20feeling%20heard%2C (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Bjursell, C.; Sädbom, R.F. Mentorship programs in the manufacturing industry. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2018, 42, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, M.L.; Williams, E.N. Working Poor Organization Behavior: Mediating Role of Mentorship and Supportive Supervisory Feedback. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2023, 37, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatinsky, N.; Cave, J.; Krauter, C. Establishing a mentorship program in rural workplaces: Connection, communication, and support required. Rural. Remote Health 2020, 20, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergle, D. Application of Gamification in Human Resource Management Processes at Enterprises and Organizations in Latvia. In Proceedings of the New Challenges of Economic and Business Development—2018: Productivity and Economic Growth, Riga, Latvia, 10–12 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Slibar, B.; Vukovac, D.P.; Lovrencic, S.; Sestak, M.; Androcec, D. Gamification in a Business Context: Theoretical Background. In Proceedings of the Central European Conference on Information and Intelligent Systems (CECIIS 2018), Varaždin, Croatia, 19–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- J Kacerauskas, T.; Sedereviciute-Paciauskiene, Z.; Sliogeriene, J. Gamification in management: Positive and negative aspects. E M Ekonomie A Manag. 2023, 26, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driskell, J.E.; Salas, E.; Driskell, T. Foundations of Teamwork and Collaboration. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konak, A.; Kulturel-Konak, S. Impact of Online Teamwork Self-Efficacy on Attitudes Toward Teamwork. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, D.; Rico, R.; Sánchez-Manzanares, M.; Salas, E. Teamwork Competency Test (TWCT): A Step Forward on Measuring Teamwork Competencies. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2014, 18, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leede, J.; Nijland, J. Understanding Teamwork Behaviors in the Use of New Ways of Working. In New Ways of Working Practices: Antecedents and Outcomes; Advanced Series in Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tjosvold, D.; Tjosvold, M. Leadership for Teamwork, Teamwork for Leadership. In Building the Team Organization: How to Open Minds, Resolve Conflict, and Ensure Cooperation; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Steegh, R.; van de Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J. Understanding how agile teams reach effectiveness: A systematic literature review to take stock and look forward. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2025, 35, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asencio, R.; Mesmer-Magnus, J.R.; Dechurch, L.A.; Contractor, N. Boundary Transitions in Dynamic Teamwork. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2024, 49, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, N.; Demir, M.; Huang, L.X. A Framework for Human-Autonomy Team Research. Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics. In Proceedings of the Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics. Cognition and Design: 17th International Conference, EPCE 2020, Held as Part of the 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Part II. Volume 12187, pp. 134–146. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holubčík, M.; Soviar, J.; Rechtorík, M.; Höhrová, P. Sustainable Development of Teamwork at the Organizational Level—Case Study of Slovakia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052031

Holubčík M, Soviar J, Rechtorík M, Höhrová P. Sustainable Development of Teamwork at the Organizational Level—Case Study of Slovakia. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052031

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolubčík, Martin, Jakub Soviar, Miroslav Rechtorík, and Paula Höhrová. 2025. "Sustainable Development of Teamwork at the Organizational Level—Case Study of Slovakia" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052031

APA StyleHolubčík, M., Soviar, J., Rechtorík, M., & Höhrová, P. (2025). Sustainable Development of Teamwork at the Organizational Level—Case Study of Slovakia. Sustainability, 17(5), 2031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052031