Abstract

The transition towards a sustainable mobility model encourages an increase in the use of soft modes of transport, and thus an increase in the number of vulnerable road users, especially in urban areas. In Spain, this group of users, comprising pedestrians, cyclists, users of personal mobility vehicles and motorcyclists, accounted for 62,258 victims in road accidents in 2023, 46% of the total, with 7258 dead or seriously injured representing 65.6% of the total. Different strategies to protect vulnerable road users, including communication campaigns, are regularly developed to increase safe travel behaviour. In this context, this study analyses the campaigns issued by the Directorate General of Traffic since 1960 aimed at vulnerable road users. Only 28 campaigns met the established inclusion criteria, representing 23.5% of the total. Thus, the period 2011–2024 has seen the lowest prevalence of this type of campaign, coinciding with a context characterised by the emergence of new forms of micro-mobility that are more sustainable but also more exposed to risks. Due to this complex environment, it is recommended to increase the prevalence of campaigns targeted at vulnerable users and to maximise their effectiveness using emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data, and delivered through a combination of traditional and digital media.

1. Introduction

The dynamics of transport and mobility of the population have evolved substantially in recent years. A growing trend towards the use of soft modes of transport (walking, cycling or Personal Mobility Vehicles) has been identified, motivated by environmental, economic and comfort reasons [1,2,3]. This transformation has a positive impact on urban mobility as it reduces traffic congestion and improves the sustainability of cities by reducing pollutant emissions [4,5]. Consequently, these individual transport modes are in line with the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda, specifically addressing SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities, SDG 3: Health and Well-being, and SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy [6]. This is why the responsible authorities are advocating the promotion of sustainable mobility in cities, carrying out specific actions through planning instruments, such as the Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans SUMPs, as well as legislative actions, such as the establishment of speed limits for traffic or the prohibition of access to certain areas for the most polluting vehicles [7,8].

Precisely due to this drive for sustainable mobility, various public and private Vehicle as a Service (VaaS) platforms have been deploying their services for years in various cities around the world, promoting private travel with bicycle, scooter or electrified motorbike rental systems that facilitate mobility in cities, especially in the case of low-demand areas [9,10,11].

However, the increase in vulnerable road users in urban and inter-urban environments poses a road safety problem [12,13]. Indeed, the latest World Health Organization report on road safety notes that users of powered two and three-wheelers account for 30% of fatalities; pedestrians make up 21% of fatalities and cyclists account for 5% of fatalities. Thus, together they account for 56% of fatalities in road crashes [14]. The figures are even higher when considering only urban areas, where the presence of cyclists is higher. Thus, in Europe, data collected by European Road Safety Observatory (2021) [15] show that vulnerable road users in urban areas account for up to 68% of road fatalities. In Latin American countries, even higher figures have been identified. In Colombia, of every 15 people involved in road crashes, half are motorcyclists and a quarter are pedestrians or cyclists [16].

This situation occurs in a context in which the number of victims travelling in passenger cars is decreasing (among other reasons, due to continuous improvements in the active and passive safety of this type of vehicles), and despite the publication of various international regulations that require the installation of certain Advanced Driving Assistant Systems (ADAS) in newly registered vehicles [17] that can help prevent crashes with pedestrians and cyclists (although to a lesser extent e-scooter riders) [18].

A specific case of this situation is the data from Spain, where car fatalities in the period 2010–2019 have decreased by 29%, while pedestrians, cyclists and powered two-wheelers users have shown variations of −8%, +14% and +1%, respectively. At the European level, these differences are less pronounced, with car fatalities decreasing by 22%, while pedestrians, cyclists and powered two-wheelers have shown variations of −18%, −2% and −18%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Average number of road fatalities by transport mode (2010–2012 and 2017–2019). Source: [15].

In any case, the increase in road accidents in this user group is not only related to the increase in vulnerable users, but also highlights the existing deficits in urban infrastructures that are not able to protect and achieve optimal coexistence between the various existing modes of travel, highlighting the need for integrative strategies to ensure the safety of all users [19]. Thus, Olszewski et al. (2018) identified that well-designed bicycle facilities and infrastructure significantly reduce accident risks, and improved pavement conditions reduce the risk for motorcyclists [20]. In addition, the importance of good road lighting is noted, as most pedestrian collisions occur at night [21]. Furthermore, specific regulatory and legislative measures have been developed that have proven to be effective in increasing the protection of vulnerable road users [22]. This is the case with the enforcement of speed reduction from 50 km/h to 30 km/h, which is associated with a decrease in the probability of dying in the crash from 50% to 5% [20].

Similarly, another factor influencing accident rates is the reckless behaviour of both road users and car drivers [23], leading to a greater sense of safety [24]. Thus, the human factor is present in more than 90% of road crashes, so that risk perception and the adoption of responsible behaviour are relevant variables to achieve a reduction in road accident rates in vulnerable road users, as well as in the population as a whole. In this sense, communication campaigns are an important tool for road safety awareness and education.

1.1. Traffic and Road Safety Communication Campaigns: The Case of Spain

The media represent a channel for direct interaction with users, enabling the dissemination of messages and raising awareness in society regarding various issues [25]. Within this framework, numerous studies support the fact that social awareness advertisements are capable of generating favourable changes, both direct and indirect, in public health habits [26,27].

In the specific case of traffic and road safety campaigns, the objectives are aimed at raising public awareness and promoting safe attitudes and behaviour on the road in order to prevent road accidents [28]. In addition, the spots can also contribute to preparing the implementation of other measures, either because the communication campaigns act as an informant or facilitator, or because they act as a complement, support and back-up to these other preventive measures that are implemented [29].

In Spain, although many public bodies and private companies have carried out actions of this type, the entity that is mainly responsible for the creation, development and dissemination of communication campaigns in the field of traffic is the Directorate General of Traffic (DGT) [30] which has an annual budget of 1.4 million euros for the design of campaigns [31], which is even higher if the cost of disseminating these campaigns in the media is taken into account. In this sense, Faus et al. (2023) carried out a detailed study of all the campaigns issued by the DGT, identifying five different periods in the evolution of their contents and communication strategies [32]. These stages are distributed as follows:

- The beginnings (1960–1978), in which the campaigns focused on the training of road users through the transmission of information on road rules and legislation by means of basic and persuasive messages.

- The soft line (1979–1991), in which the consequences of not respecting the rules began to be made visible, although generally with a less visually aggressive approach, generating a low emotional impact on the viewer.

- The hard line (1992–1997), a substantial change in communication strategy, with realistic and violent messages and images showing the aversive consequences of road accidents in the short and long term.

- Multivariate period (1998–2010), characterised by the alternation between shocking, informative and emotional advertisements to avoid desensitising the viewer, promoting the idea of individual responsibility of users.

- Last years (from 2011 onwards), a stage in which the aim is to deepen the audience’s reflection, using different communication strategies and considerably improving the audiovisual quality of the advertisements.

1.2. Aims of the Study

The research aims to analyse the prevalence, message evolution and communication strategies of traffic campaigns targeting vulnerable road users in Spain, as well as to evaluate their possible impact on registered accident rates. The study will include traffic advertisements aimed at pedestrians, cyclists, electric scooter users and motorcyclists, as well as those aimed at vulnerable age groups, specifically children and the elderly.

2. Materials and Methods

For the purposes of the study, a selection of traffic and road safety communication campaigns targeting vulnerable road users has been made. The study sample was determined through an exhaustive review of the available databases based on specific criteria. Subsequently, a description and analysis of the content of the spots has been carried out, allowing the identification of their main characteristics and the drawing of conclusions.

2.1. Determining the Sample of Communication Campaigns in the Study

Campaign-specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined based on the theme, area of application, broadcaster, dissemination platform and availability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the selected campaigns.

A search and selection of campaigns targeting vulnerable road users between March 2024 and June 2024 was carried out through online video playback platforms such as YouTube (among others). A total of 119 traffic, mobility and/or road safety communication campaigns that were broadcast from 1960 to 2024 were identified as available for viewing. Of these, there are 28 campaigns that fall within the thematic area analysed, meeting all the inclusion criteria described. Therefore, these spots were downloaded and registered for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Procedure for Coding Variables and Data Processing

The selected campaigns were reviewed by three independent judges, who carried out a content analysis to identify the communication strategies employed, as well as other formal elements such as message, images and audiovisual content.

The spots were registered considering the following variables:

- (1)

- Campaign message and/or main slogan.

- (2)

- Year of broadcast, identifying their correspondence with the period of DGT campaigns in which they were broadcast.

- (3)

- Subject matter, differentiating between specific ads for vulnerable users and those that address this issue within a broader campaign on risk factors.

- (4)

- Communication strategy employed in the following categories:

- Informative (Real images): Real scenes and people in the advertisements, without violent images, with the aim of educating the viewer about the problem in a positive tone.

- Informative (Animations): Cartoons, animations or figures that illustrate a problem in a clear and visual manner.

- Metaphorical: Symbols, comparisons or analogies used to help understand of the message being conveyed.

- Emotional (Impact): Realistic and aggressive scenes of road accidents, victims and their consequences, to create surprise and impact on the viewer.

- Emotional (Testimonial): Testimonials from real people sharing their personal experiences as victims or families of the victims of road accidents to evoke sympathy from the audience.

In addition, a detailed description of each advertisement was carried out, highlighting the content and the communication strategies employed.

Finally, a content analysis and representation of the results in figures showing the presence of these advertisements among the DGT campaigns was carried out, in order to observe the evolution and changes in traffic and road safety campaigns aimed at vulnerable users, through quantitative and qualitative approaches.

3. Results

A total of 28 traffic and road safety communication campaigns were selected because they fit the subject matter analysed. The presence of this typology of campaigns has been uneven in the five periods in relation to their frequency and the communicative resources used (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of vulnerable user campaigns in the stages of traffic campaigns in Spain.

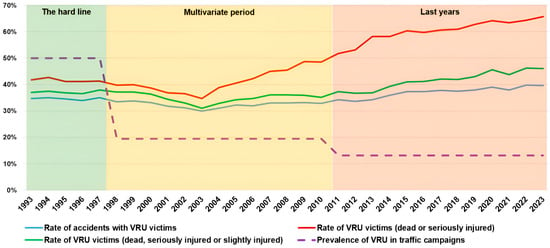

The relationship between the prevalence of this type of campaign and the accident figures for vulnerable road users is shown in Figure 1. This shows a decreasing trend in the number of accidents involving vulnerable road users and the number of victims recorded in these accidents until 2003, when there was a turning point that reversed the trend up to the present day.

Figure 1.

Percentage of vulnerable road user (VRU) accidents and their victims against the prevalence of VRU campaigns broadcasted in Spain. Period 1993–2023. Source: [33].

It can be seen that the sustained growth in their accident rate coincides with the period of lower prevalence of campaigns targeting vulnerable road users. In fact, over the entire period 2011–2023, more than 50% of the people dead or seriously injured in road accidents in Spain were vulnerable road users, while only 13.1% of the communication campaigns were aimed at this type of users. Furthermore, in the year 2023, 65.6% of the total number of people dead or seriously injured in road accidents were vulnerable road users, the highest rate in the series analysed. In any case, it cannot be affirmed that there is a direct relationship between the number of communication campaigns and the variation in accident figures, given that the dissemination of awareness-raising messages forms part of a set of prevention actions that are applied simultaneously, and the effect of each of them cannot be evaluated independently.

Table 4 presents an overview of all available campaigns that raise awareness of the special risk of vulnerable road users. About 25% (n = 7) of the campaigns are exclusively oriented towards pedestrians, addressing issues such as safe crossing of streets or the importance of respecting traffic rules. Examples are “Look first, then cross” (1963) and “The pedestrian’s first rule of the road is common sense” (2002), which urges both drivers and pedestrians to act responsibly at designated pedestrian crossing points. More recently, “The Most Famous Pedestrian Fatalities” (2022) uses public figures in their role as pedestrians to raise awareness of vulnerability on inter-urban roads.

Table 4.

Description of vulnerable user campaigns of the DGT.

On the other hand, 42.8% (n = 12) of campaigns focus on the safety of motorcyclists, with a strong emphasis on helmet use. From early campaigns such as “Wear… helmets” (Usen… casco, 1964) to current spots such as “The Glass Man” (2018), the message has evolved from purely educational approaches to impactful and emotional representations. Thus, “Get it through your head” (1991) uses visual metaphors to show the damage a crash can cause without a helmet, while “You can change reality” (2008) uses an actor’s testimony to reflect on the responsibility of drivers towards motorcyclists.

Child protection accounts for 14.3% (n = 4 spots) of the total, highlighting educational messages aimed at both children and their families. Spots such as “The weakest need more protection” (1967) underline the importance of teaching children how to ride safely. In more recent years, the campaign “If you don’t fasten your child restraint system, it’s as if you’re not wearing one” (2013) reinforces the idea of safety measures for children, with an emphasis on the role of the people around them as caregivers and responsible for their safety as road users.

Recently, campaigns aimed at electric scooter users have been launched. In the selection, one spot has been identified with 3.5% (n = 1) with the title “The most dangerous thing is that it doesn’t look dangerous” (2024). However, since 2021, more local campaigns have been developed in many Spanish regions, which have not been included because they do not respond to a national scope, but which express the current concern about this group and their behaviour on the road.

Some of the spots (10.7%; n = 3) are generalist campaigns covering different types of vulnerable road users in the same message. These campaigns, such as “Look first, then cross” (1963), promote a general awareness of a preventive measure by targeting different groups of road users such as motorcyclists, cyclists, pedestrians and also drivers (although these do not represent a vulnerable group). “Move consciously” (2015) is another example, promoting both cycling and public transport as responsible alternatives to private vehicles.

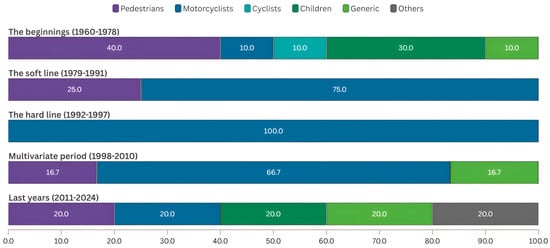

Figure 2 shows the differences in each time period according to the type of vulnerable user targeted by the traffic campaigns. Thus, there are stages such as the beginning and the last years in which there are campaigns aimed at different groups of users. While in other periods, such as the hard line, there is a special focus on a specific group, in this case motorcyclists, and especially on the preventive behaviour of helmet use. In any case, it should be noted that the number of campaigns on vulnerable road users is small compared to the total number of traffic spots as most campaigns focus on car drivers (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Specific theme of the vulnerable user campaigns in Spain.

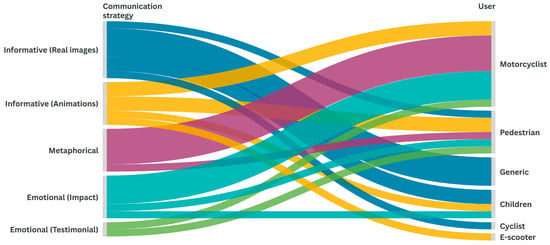

In terms of communication strategies and message tone, there is a high prevalence of informative spots targeting vulnerable users. These advertisements tend to convey a clear and concise message, often repeated in an insistent and persuasive manner to reinforce their impact. The high presence of this type of advertisement is influenced by the period in which they were broadcast, as 10 of the 28 advertisements identified were broadcast during the ‘beginnings’ stage, a time when user education was the main objective of traffic and road safety campaigns in Spain.

Within the informative spots, in half of the cases, real images are used, while in the other half, animations and graphic images are used to facilitate the understanding of the message (Figure 3). These advertisements are aimed at various groups of vulnerable road users, either generally or especially at specific target groups such as pedestrians and children. In the case of children, the educational character is reinforced by animations to better capture their attention. However, one spot is identified in which emotional impact techniques are used (If you don’t fasten your child restraint system, it’s as if you’re not wearing one, 2013). In this case, the campaign does not target children directly, but their parents, seeking to generate a change in their behaviour by encouraging the use of safety systems when children are passengers in motorised vehicles.

Figure 3.

Relationship between the communication strategy and the target audience.

On the other hand, motorcyclists have a scarce presence in informative advertisements. In their case, the spots tend to employ high-impact emotional strategies, resorting to shocking and realistic images of road accidents, which therefore present a certain degree of crudeness, in order to generate a shock effect on the viewer. There is also a sustained presence of advertisements with metaphorical approaches, in which the vulnerability of the motorcyclist is made visible through comparison with certain resources (for example in ‘The Glass Man’ (2018). In these spots, the importance of helmets and equipment for motorcyclists as effective and indispensable protective devices is often emphasised.

For pedestrians, the messages have been very diverse over time, including informative, emotional and testimonial spots. On the other hand, it is difficult to draw conclusions about cyclists and e-scooter users, as they have been the target of few traffic spots. Nevertheless, they are emerging figures, especially e-scooter users, who will be the focus of both national and local campaigns in the coming years due to their growing importance in the context of micro-mobility.

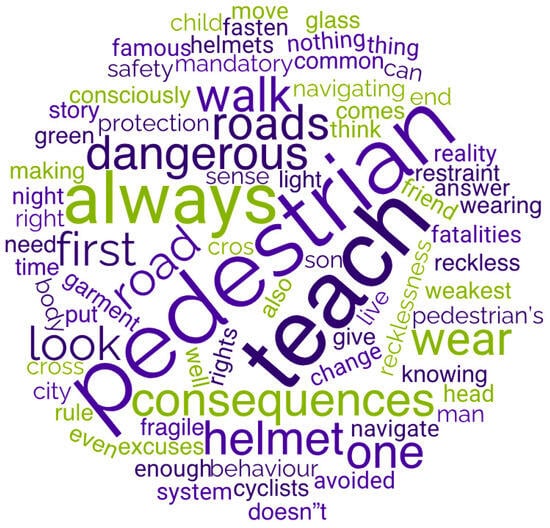

The tone of the campaign messages is reflected in the slogans. Figure 4 represents a word cloud identifying the most repeated concepts in the messages of the campaigns aimed at vulnerable users. The words that stand out the most are ‘pedestrian’, ‘teach’, ‘always’, ‘walk’ which are presented especially in the educational and training advertisements, especially in the period of ‘the beginnings’. Terms more related to motorbike users also stand out, showing a relationship with the aversive consequences to which this road group may be exposed, with words such as ‘helmet’, ‘consequences’, ‘dangerous’ and ‘road’.

Figure 4.

Word cloud of the slogans of the campaigns targeted at vulnerable users.

4. Discussion

The aim of the research is to analyse the different communication strategies adopted in Spanish awareness campaigns expressly aimed at the protection of vulnerable users. More specifically, this research aims to determine both the effectiveness of the campaigns themselves and the influence that the different regulatory and cultural changes have had on them. In addition, it aims to determine a series of reflections on the future challenges in this area.

4.1. The Evolution in Campaign Design: Different Target Audiences and Changes in Communication Strategies

It is identified that the prevalence of vulnerable users in traffic campaigns is low, with only 23.5% of the spots presenting content on this issue. This is especially significant in the last of the stages mentioned in Table 1, as during the period 2011–2024 only 13.1% of the total were identified. In contrast, car drivers are the road group most represented in Spanish [32] and international [35] awareness campaigns. In addition, car drivers are also over-represented in general advertising. Along these lines, those spots that present various risk behaviours within the same generic message or slogan include practically only actions carried out by this road group, and to a much lesser extent, risk behaviours of other user groups are included. Thus, only in some cases, such as the campaign “Reckless behaviour has more and more consequences” (1992), are some scenes of motorcyclists shown, highlighting the importance of the compulsory use of helmets as a preventive measure for injuries resulting from road accidents, a scene that is relevant to other situations involving risky behaviour by car drivers.

To some extent it is logical that the main protagonists of traffic and road safety campaigns are car drivers. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, because passenger cars accounted for 70.7% of the national vehicle fleet in 2022 and 85.3% of the mobility figures on the state road network [36]. Therefore, the presence of drivers of passenger cars is much higher than that of drivers of other means of transport. Secondly, because their interaction results in the highest number of recorded casualties. In fact, in the year 2023 alone, 48.1% of the traffic accident victims recorded in Spain were due to interaction with a single passenger car [30] because their offending behaviour can have particularly aversive consequences for other, more vulnerable road users (among other reasons) [37,38,39]. In this sense, communication campaigns focus their message on the risk factors most related to road accidents, such as speeding, alcohol and drug use and distractions with mobile phones [40,41,42].

However, in the same way, risky behaviours of pedestrians, cyclists and scooter users can also trigger serious road crashes [43,44], which has been of particular concern in recent years due to the rise of micro-mobility. Indeed, this is a group of users who may not necessarily have received road safety training and who commit a high number of offences that, in practice, are often not sanctioned by the competent authorities [45,46]. This is a matter of concern and should be addressed by the responsible authorities with concrete actions related to road safety training programmes and awareness campaigns specifically targeting vulnerable road users. However, the trend in the number of spots in recent years of this typology is not upward and, moreover, it is very diversified so that there are really few advertisements specific to each of the mentioned user groups.

In relation to the communicative strategy in the campaigns, this has been in accordance with the way of transmitting the messages in the stages in which they were issued. Thus, at the beginning, advertisements are broadcast with simple messages that aim to inform the population of the correct behaviours to be performed by different types of vulnerable users, as well as the attitudes and actions that other users should take into account in order to avoid road incidents or accidents with them [32]. Therefore, they present a mainly educational approach, where facts and clear instructions are the main elements such as “Look first, then cross” (1963). Subsequently, with the arrival of the 1990s, the messages and images of the spots became stronger. Thus, the tone began to include a greater emotional charge, with testimonies of victims (“The story of…”, 1994) or shocking scenes showing the consequences of breaking the rules (“Reckless behaviour has more and more consequences”, 1992). These campaigns seek to provoke empathy and to reflect on the personal and family consequences of accidents [47]. In the following stages, especially from the 2000s onwards, the communication strategy changed again. The message is further diversified by adopting metaphorical or even humorous strategies. Campaigns such as “The Glass Man” (2018) use innovative and symbolic visual resources to represent human fragility in the face of an accident. Therefore, these are years in which heterogeneous techniques are used, ranging from informative elements to campaigns with a high emotional impact. But also other more creative strategies through comparisons, exaggerations and using resources from emerging technologies such as big data or artificial intelligence with the aim of capturing the attention of the viewer and increasing their awareness of the risks of these types of users’ journeys [48].

4.2. Preliminary Analysis of the Impact of Campaigns Targeting Vulnerable Road Users on Road Accident Rates

Road accidents are a complex phenomenon that needs to be tackled from different perspectives. One of these is to raise awareness of the problem. In this sense, and as previously mentioned, the dissemination of communication campaigns allows, through different strategies, to have an impact on the viewers. However, this impact is difficult to quantify if only the date of publication of the campaign is contrasted with the variation in accident figures, as its synergy with other preventive actions such as road safety education, police controls, penalties, improvements in infrastructure and vehicles, among other measures that are applied concurrently, are not considered [49,50,51]. In any case, it has been possible to identify certain divergences between the prevalence of the campaigns and the variations in the accident rates of vulnerable users, a fact that can be understood as a first approximation to the analysis of their impact.

For the aforementioned analysis, the accident, mortality and morbidity figures provided by the Directorate General of Traffic, and more specifically those affecting vulnerable users, whose first disaggregated figures date back to 1993, were used. Although this fact has limited to some extent the time range under study, it is considered equally interesting for the analysis, since in addition to showing a broad perspective (30 years in total), it has served to understand that the sustained increase in the rates of vulnerable road user victims of traffic accidents recorded since 2003 contrasts with the decrease in the presence of awareness campaigns aimed at vulnerable road users, which is mainly made up for by campaigns aimed at car drivers. Therefore, there is a substantial difference between the number of spots aimed at car drivers and those aimed at vulnerable road users, the latter being a much more heterogeneous group as it includes pedestrians, cyclists, motorcyclists and others.

Thus, the idea that preventive actions aimed at raising awareness (especially communication campaigns) are mostly focused on car drivers, when they are precisely the group of users that are registering the best trends, is once again being reinforced. In Spain, whereas in 1993, 50.5% of people dead or seriously injured were travelling in cars, in 2023 they accounted for only 7.2% [30]. Moreover, this differentiation is even more acute if we consider the communication strategies employed. If we take into account all the spots analysed, only 28.5% of these spots have an emotional component (either in the form of impact or victim testimonies), while the rest are informative or metaphorical in tone [34]. Therefore, if the majority of the spots do not generate surprise or reflection, they potentially capture the user’s attention less and are less remembered. The presence of the aggressive tone in the campaigns aimed at car drivers was the main one during the hardline, and in the following stages, even if it was interspersed with other communicative strategies, it remains one of the most present.

Therefore, the effectiveness of these campaigns might be lower compared to those targeting car drivers, not only because of their lower media presence, but also because they tend to be less impactful or less remembered. Therefore, it is recommended not only to increase the frequency of campaigns targeting vulnerable road users, but also to modify the focus of the messages to enhance their impact. In relation to this, an aggressive tone is not always recommended in traffic spots, but it is preferable to intersperse different strategies to avoid habituation and desensitisation of the audience to violent images and loss of effectiveness [32]. This is especially relevant in campaigns aimed at drivers due to their high presence as protagonists of these messages. However, in the case of vulnerable users, given that campaigns aimed at this group are more sporadic, it is recommended to reduce purely informative messages and prioritise an emotional approach in practically all the (few) spots available, thus encouraging identification and reflection in the target audience.

4.3. Influence of Regulatory and Cultural Changes on Traffic and Road Safety Campaigns

One of the main purposes of communication campaigns is to inform the population of legislative changes in road safety and to facilitate their acceptance and implementation in the region [52,53]. A paradigmatic case in point is the implementation of the driver’s points-based licence in Spain in 2006. This new measure represented a substantial change in the way drivers were penalised, and many information and educational campaigns were launched at both national and regional levels to ensure that the entire population understood how the new system worked, as well as its benefits as an effective tool for reducing road accidents. Along these lines, social acceptance is an important variable for the effectiveness of the measures implemented, an aspect that can be modulated through appropriate communication with the population [54,55].

This correspondence between legislative changes and awareness-raising campaign messages has been applied over the years with other measures such as the compulsory use of seat belts in campaigns such as “For your safety, wear your seat belt” in 1973, or the reduction in the blood alcohol limit for drivers in campaigns such as “Always one drink too many” in 1978. However, messages aimed at vulnerable road users have also been developed in line with legislative changes. This is the case for the compulsory use of helmets by motorcyclists, a message that has been sustained over time and is maintained today, with campaigns such as “The helmet, the only mandatory garment” in 1981 or “Always wear a helmet, even in the city” in 2009. In relation to this, it is worth also highlighting the functionality of campaigns as agents for the promotion of changes in social attitudes and perceptions. Thus, they can contribute to reducing resistance to change, as the compulsory wearing of helmets is a safety measure that was initially met with some cultural resistance, which meant that the communication strategy had to emphasise the aversive consequences of engaging in these risky behaviours. As a result of this, as well as other actions that were developed, today helmet use is a measure that is widely accepted, with the percentage of use in Spain ranging from 99% on urban roads to 100% on interurban roads [12].

In addition, specific campaigns have been carried out to alert drivers to behaviours that increase the risk of vulnerable road users being involved in road crashes [56]. This is the case of messages aimed at car drivers to point out the importance of keeping a safe distance when overtaking cyclists, or the mandatory use of child restraint systems to prevent injuries to child passengers in vehicles, with campaigns such as “If you don’t fasten your child restraint system, it’s as if you don’t have one” in 2013.

Additionally, cultural changes can also influence the content and design of traffic campaigns. Beliefs about sustainability and people’s willingness to act against pollutant emissions drive the use of bicycles, Personal Mobility Vehicles and public transport [57,58]. These aspects are promoted and emphasised by campaigns that seek to raise awareness and further encourage their adoption, highlighting benefits such as faster travel times, improved urban mobility and reduced congestion. Thus, the most recent campaigns not only focus on road safety, but also on promoting these modes as responsible and healthy alternatives [59,60]. In the campaign “Move with consciously” (2015), a play on words refers both to the sustainability of soft modes of transport, but also to the increased vulnerability of soft modes of transport as users. This spot not only aims to increase the use of these modes of transport for their collective and individual benefits, but also to make drivers aware of the presence of vulnerable road users in urban and interurban areas to ensure safe coexistence on the roads.

In any case, and despite this, in the case of electric scooter users, this cultural change has not yet been fully assimilated, as evidenced by the scarcity of specific messages for this group. The use of Personal Mobility Vehicles shows an upward trend, especially since 2020 due to the modal shift resulting from COVID-19-related restrictions [61,62]. Similarly, an increase in the number of fatalities and injuries in accidents involving these vehicles has also been identified [46,63]. In this sense, social and commuting changes are occurring very quickly. And, in the case of electric scooters, this speed means that the relevant legislative changes have not been made at the same speed. Thus, in line with this, the debate arises as to whether current awareness campaigns respond quickly enough to these mobility dynamics, especially in a context of urban transformation. However, the opportunity also arises that the messages of the spots can even anticipate certain legislative changes, in order to achieve attitudinal and behavioural change in users without the imposition of certain punitive and sanctioning measures.

4.4. Future of Campaigns Targeting Vulnerable Users: Challenges and Recommendations

In line with the above, traffic campaigns must adapt to the new challenges of urban mobility, especially with the irruption of Personal Mobility Vehicles due to the risks that this new means of transport presents and which are already being evidenced in the accident rate data. In fact, data for 2023 in Spain indicate a 37.5% increase in the number of deaths in accidents involving personal mobility vehicles [64]. Specifically, 66% of fatalities and serious injuries are caused by collisions with other vehicles, while 23% are due to e-scooter falls.

Consequently, the design and dissemination of communication campaigns aimed at e-scooter users is urgently needed. In view of the apparent disparity in the regulations governing travel by this means of transport, a sequential and complementary approach to campaigns is recommended, including spots at national and local level. In such a way that the viewer first sees spots and messages with the basic regulatory aspects and recommendations to common users, such as the use of helmets. This first step allows the dissemination of concrete ideas necessary for the proper coexistence of e-scooter users with other road users, through multiple platforms and communication channels of national scope. Subsequently, the regions or municipalities that require it can complement the common message with new campaigns that follow up and reinforce these ideas, but that are also adjusted to the needs and particularities of regulations, infrastructure and micro-mobility in each of these specific regions. Thus, campaigns at the local level allow for awareness-raising on specific issues in a geographical area, such as hotspots for this road group, as well as direct action in local public spaces and streets. This would be particularly interesting in countries such as Spain, where responsibility for urban mobility is devolved to the regions (which is precisely where e-scooters circulate).

In addition, it should be considered that e-scooter users are generally teenagers and young people with little road safety training [65]. Thus, personal mobility vehicles have become popular as inexpensive modes of transport, which can replace cars and motorbikes, and which do not require a driving licence to use [66]. Therefore, people using this mode of transport may lack road experience and may not be aware of basic traffic rules. In addition, young age is also associated with low risk perception and reckless and offending behaviour [67,68]. Furthermore, there is a perception in certain sectors of the population that identifies the electric scooter as a toy rather than a means of transport, leading to a reduced subjective risk perception of its use.

Along these lines, and based on the characteristic socio-demographic factors of the people who use this mode of transport, it is recommended that the communication channel for future campaigns on personal mobility vehicles should be online social networks [69]. However, this poses relevant challenges for the communication strategy. The social media format facilitates quick access to a large amount of information but also misinformation [70,71]. Moreover, campaigns delivered through these channels can be quickly forgotten or even ignored if the user chooses not to pay attention to the advertisement [72]. Therefore, different processes take place compared to traditional media such as radio or television in which the viewer has less decision-making power over the content he or she views. One possible solution to this limitation is the use of big data, artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies. These tools make it possible to identify viewers’ preferences and show them information tailored to their interest [48]. Therefore, it is possible to determine the population that is potentially interested in road safety messages and to promote their exposure to them in order to increase their education in this area. However, this strategy does not make it possible to reach the entire population, excluding precisely those who may have less knowledge of the rules and the risk posed by certain behaviours.

In this respect, for some years now, live campaigns have been generated using emerging technologies in real time, through street posters and interactive billboards that capture the attention of road users and allow high-impact messages to be conveyed. These technologies have been used in some countries such as France in their pedestrian campaign “Ne prenez pas le risque de voir la mort en face” (Don’t risk seeing it head-on) [73]. Another case of campaigns using this technology is the one issued by SAAQ (Société de l’assurance automobile du Québec, 2018 [74] with the slogan ‘Bones vs. Steel’. This campaign consists of installing screens in the street that detect and reflect the skeleton of pedestrians walking along the road, and after a few minutes in which the silhouette follows the movements of the user, a vehicle abruptly runs over this image, generating surprise and impact on the viewer. In the few cases in which this technology has been applied, it has generally been aimed at pedestrians, but these are tools that could be very useful for raising awareness among e-scooter users. Some ideas for carrying out this type of awareness-raising actions are the implementation of sensors that measure the speed of scooters and issue personalised messages in real time to their users (as long as they do not distract them from driving) or setting up screens in shared scooter stations or high traffic areas of this means of transport that represent the image of the user and simulate the consequences of an accident if they are not wearing a helmet, as well as the consequences that their imprudent behaviour can have for other road users.

All these factors highlight the need to develop communication actions for the population as a whole in order to encourage greater responsibility in their journeys and to generate greater empathy and protection for vulnerable users. In any case, campaigns should complement and correspond to updated legislation adapted to the new needs of today’s prevailing modes of transport.

4.5. Limitations of the Study and Future Lines of Research

The present research highlights the scarcity of traffic and road safety campaigns targeting vulnerable road users in Spain. However, the selection process of the spots has some limitations related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. On the one hand, an analysis was made of campaigns broadcast at the national level. Therefore, regional initiatives that could include this typology of users have been excluded. In this sense, future research should analyse the characteristics of traffic campaigns issued at the local level since, due to the fact that they address mobility problems in urban areas, they may contemplate the risks of pedestrians, cyclists and users of personal mobility vehicles to a greater extent.

On the other hand, the availability of the audiovisual pieces of the campaigns is limited. Although several databases have been used to extract the spots, it is possible that some spots were not included in any of the media consulted. Potential access problems may have occurred especially in the spots broadcast in the first historical periods analysed.

With regard to the analysis of the effectiveness of the campaigns, it should be stressed that the study carried out is a preliminary analysis which in no case aims to establish a direct and unique relationship between the type of campaigns issued and the road accident figures in Spain, given the impossibility of evaluating their impact independently of other concurrent preventive measures.

In any case, the research carried out represents a first approach to the figure of vulnerable users as protagonists of traffic and road safety campaigns. In future studies, the impact of these advertisements should be evaluated, not limiting the analyses to a descriptive characterisation, but quantifying the impact of the spots on recall and their effectiveness in changing the behaviour of the population.

5. Conclusions

For this research, a total of 28 communication campaigns on traffic and road safety designed by the Spanish Directorate General of Traffic in the period 1960–2024 and broadcast by audiovisual media were analysed. All of them aimed at improving the safety and mobility of vulnerable road users. Thus, it has been determined that the prevalence of traffic campaigns aimed directly at vulnerable road users has been decreasing over time. While 23.5% of the campaigns developed in the period 1960–2024 met the requirements for inclusion in this study, only 13.1% of those disseminated in the period 2011 to 2024 did so. All of this occurred in a context marked by the rise of urban micro-mobility and an increase in the accident rate of vulnerable road users, which reached its highest figures in 2023.

In addition, it is noted that traffic and road safety campaigns have traditionally been sensitive to regulatory and cultural changes. Thus, it is understood that it would be possible to make a greater effort to design both awareness campaigns that warn of the dangers of micro-mobility and the increase in accident rates among vulnerable groups and information campaigns that inform citizens of the different legislative changes that are being adopted to improve safety on the roads, especially with regard to e-scooters.

Therefore, efforts should be made to increase the prevalence of campaigns aimed at vulnerable users, as although it is not possible to establish a direct relationship between the number of campaigns carried out and variations in accident figures, the scientific literature highlights their effectiveness as a preventive measure, especially when they complement other preventive actions. In addition, the design of future campaigns must take into account the changes that society is experiencing, particularly in terms of how to reach the target audience. In this way, the combined use of traditional communication techniques and channels, such as television advertisements, together with other media such as social networks or interactive signage systems supported by big data or artificial intelligence techniques, would allow a greater and better dissemination of messages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.F. and F.A.; methodology, M.F.; validation, F.A. and C.E.; formal analysis, M.F.; investigation, M.F. and J.L.V.; resources, F.A. and C.E.; data curation, M.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.F. and J.L.V.; writing—review and editing, M.F., F.A., C.E. and J.L.V., supervision, F.A. and M.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is part of a doctoral thesis, supported by the research grant ACIF/2020/035 (MF) from “Generalitat Valenciana”. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Arash Javadinejad (authorised translator) for professional editing of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Şengül, B.; Mostofi, H. Impacts of E-Micromobility on the sustainability of urban transportation—A systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe-Falgas, P.; Madrid-Lopez, C.; Marquet, O. Assessing environmental performance of micromobility using lca and self-reported modal change: The case of shared e-bikes, e-scooters, and e-mopeds in barcelona. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankey, S.; Lindsey, G.; Wang, X.; Borah, J.; Hoff, K.; Utecht, B.; Xu, Z. Estimating use of non-motorized infrastructure: Models of bicycle and pedestrian traffic in Minneapolis, MN. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 107, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, C.; Brereton, F.; Bailey, S. The economic contribution of public bike-share to the sustainability and efficient functioning of cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 28, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, D.; D’apuzzo, M.; Evangelisti, A.; Nicolosi, V. Towards sustainability: New tools for planning urban pedestrian mobility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A systematic literature review. Relationships between the sharing economy, sustainability and sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Court of Auditors. Special Report Reaching EU Road Safety Objectives Time to Move up a Gear. 2024. Available online: https://www.eca.europa.eu/ECAPublications/SR-2024-04/SR-2024-04_EN.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Olabi, A.G.; Wilberforce, T.; Obaideen, K.; Sayed, E.T.; Shehata, N.A.; Alami, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Micromobility: Progress, benefits, challenges, policy and regulations, energy sources and storage, and its role in achieving sustainable development goals. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 17, 100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Deng, Y.; Ding, H.; Qu, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Fang, Y. Vehicle as a service (VaaS): Leverage vehicles to build service networks and capabilities for smart cities. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 26, 2048–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, X.; Marquet, O.; Miralles-Guasch, C. Assessing social and spatial access equity in regulatory frameworks for moped-style scooter sharing services. Transp. Policy 2023, 132, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, N.; Pilla, F.; y Carroll, P. The social sustainability of cycling: Assessing equity in the accessibility of bike-sharing services. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 106, 103490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannis, G.; Nikolaou, D.; Laiou, A.; Stürmer, Y.; Buttler, I.; Jankowska-Karpa, D. Vulnerable road users: Cross-cultural perspectives on performance and attitudes. IATSS Res. 2020, 44, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branion-Calles, M.; Götschi, T.; Nelson, T.; Anaya-Boig, E.; Avila-Palencia, I.; Castro, A.; Winters, M. Cyclist crash rates and risk factors in a prospective cohort in seven European cities. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 141, 105540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240086517 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- European Road Safety Observatory. National Road Safety Profile—Spain. 2021. Available online: https://road-safety.transport.ec.europa.eu/document/download/d2e7b66b-1cfd-422a-a36c-b2be1cff49e5_en?filename=erso-country-overview-2023-spain_0.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Bonilla Verdugo, D. Arquitectura de Infraestructura y Modelo de Optimización para la Reducción de la Probabilidad de Accidentes de Usuarios Vulnerables en la vía Pública. Sistemas y Computación en Universidad de los Andes, Colombia. 2020. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1992/43900 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2019/2144 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on Type-Approval Requirements for Motor Vehicles and Their Trailers, and Systems, Components and Separate Technical Units Intended for Such Vehicles, as Regards Their General Safety and the Protection of Vehicle Occupants and Vulnerable Road Users. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019R2144 (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- European Transport Safety Council. Improving the Road Safety of E-Scooters PIN Flash Report 47; European Transport Safety Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, D.; Mitra, S. Impact of road infrastructure land use and traffic operational characteristics on pedestrian fatality risk: A case study of Kolkata, India. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2019, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, P.; Szagała, P.; Rabczenko, D.; Zielińska, A. Investigating safety of vulnerable road users in selected EU countries. J. Saf. 2018, 68, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.L.; Schneider, R.J.; Proulx, F.R. Pedestrian fatalities in darkness: What do we know, and what can be done? Transp. Policy 2022, 120, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguridad Vial, PONS. Los Vulnerables [Online]. Madrid. 2023. Available online: https://ponsseguridadvial.com/los-vulnerables/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Komol, M.M.R.; Hasan, M.M.; Elhenawy, M.; Yasmin, S.; Masoud, M.; Rakotonirainy, A. Crash severity analysis of vulnerable road users using machine learning. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 0255828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torfs, K.; Meesmann, U. How do vulnerable road users look at road safety? International comparison based on ESRA data from 25 countries. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2019, 63, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais Pinto, R.; de Medeiros Valentim, R.A.; Fernandes da Silva, L.; Góis Farias de Moura Santos Lima, T.; Kumar, V.; Pereira de Oliveira, C.A.; Andrade, I. Analyzing the reach of public health campaigns based on multidimensional aspects: The case of the syphilis epidemic in Brazil. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faus, M.; Alonso, F.; Javadinejad, A.; Useche, S.A. Are social networks effective in promoting healthy behaviors? A systematic review of evaluations of public health campaigns broadcast on Twitter. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1045645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, H.; Koßmann, I. The role of safety research in road safety management. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faus, M.; Alonso, F.; Fernández, C.; Useche, S.A. Are traffic announcements really effective? A systematic review of evaluations of crash-prevention communication campaigns. Safety 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Tráfico (DGT). Principales Cifras de Siniestralidad en España 2023 [Online]; España. 2024. Available online: https://www.dgt.es/menusecundario/dgt-en-cifras/dgt-en-cifras-resultados/dgt-en-cifras-detalle/Las-principales-cifras-de-la-siniestralidad-en-Espana-2023/#:~:text=Analizando%20las%20cifras%20registradas%20durante,un%203%25%20las%20v%C3%ADctimas%20mortales (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Dirección General de Tráfico. Plan De Campañas De Divulgación De La Seguridad Vial, Comunicación Interna Y Comunicación Institucional De La Direccion General De Tráfico. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-B-2024-32944 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Faus, M.; Fernández, C.; Alonso, F.; Useche, S.A. Different ways… same message? Road safety-targeted communication strategies in Spain over 62 years (1960-2021). Heliyon 2023, 9, 18775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección General de Tráfico (DGT). DGT en cifras [Online]; España. 2025. Available online: https://www.dgt.es/menusecundario/dgt-en-cifras/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Dirección General de Tráfico (DGT). Campañas [Online]; España. 2024. Available online: https://www.dgt.es/comunicacion/campanas/ (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Elvik, R. A theoretical perspective on road safety communication campaigns. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 97, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Transportes y Movilidad Sostenible. Anuario estadístico. Capítulo 8. 2023. Available online: https://www.transportes.gob.es/recursos_mfom/paginabasica/recursos/08trafico_22.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Johnsson, C.; Laureshyn, A.; De Ceunynck, T. In search of surrogate safety indicators for vulnerable road users: A review of surrogate safety indicators. Transp. Rev. 2018, 38, 765–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bíl, M.; Bílová, M.; Dobiáš, M.; Andrášik, R. Circumstances and causes of fatal cycling crashes in the Czech Republic. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2016, 17, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hern, S.; Oxley, J. Fatal cyclist crashes in Australia. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19 (Suppl. S2), S27–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinar, D. Crash causes, countermeasures, and safety policy implications. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 125, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogstrand, S.T.; Larsson, M.; Holtan, A.; Staff, T.; Vindenes, V.; Gjerde, H. Associations between driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, speeding and seatbelt use among fatally injured car drivers in Norway. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 78, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Herrero, S.; Febres, J.D.; Boulagouas, W.; Gutiérrez, J.M.; Mariscal Saldaña, M.A. Assessment of the influence of technology-based distracted driving on drivers” infractions and their subsequent impact on traffic accidents severity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesimäki, J.; Luoma, J. Near accidents and collisions between pedestrians and cyclists. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Labi, S.; Zhu, S. Understanding electric bike riders’ intention to violate traffic rules and accident proneness in China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 23, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.; Rakotonirainy, A. Can rail pedestrian violations be deterred? An investigation into the threat of legal and non-legal sanctions. Transp. Res. F-Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 45, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehranfar, V.; Jones, C. Exploring implications and current practices in e-scooter safety: A systematic review. Transp. Res. F-Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 107, 321–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J.I.; Castro-Nuño, M.; Pedregal, D.J. How many lives can bloody and shocking road safety advertising save? The case of Spain. Transp. Res. F-Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2012, 15, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faus, M.; Alonso, F.; Fernández, C.; Esteban, C. Use of big data, artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies in public health communication campaigns: A systematic review. Rev. Commun. Res. 2025, 13, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, R.B. Traffic fatalities and injuries: The effect of changes in infrastructure and other trends. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallmark, S.; Wood, J.; Basulto-Elias, G.; Hans, Z.; Litteral, T.; Oneyear, N.; Kunert, M.R. Combined High-Visibility Enforcement: Determining the Effectiveness; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dragutinovic, N.; Twisk, D. The Effectiveness of Road Safety Education: A Literature Review; SWOV Institute for Road Safety Research: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kithae, P.P. Traffic law enforcement, road safety campaigns, and behavior change among road users in Kenya. Int. J. Interdiscip. Civ. Political Stud. 2022, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamos, G.; Ausserer, K.; Brijs, K.; Brijs, T.; Daniels, S.; Divjak, M.; Tamis, K. A Theoretical Approach to Assess Road Safety Campaigns: Evidence from Seven European Countries; Forward, S., Kazemi, A., Eds.; CAST; Belgian Road Safety Institute: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, R.N.; Sarma, K.M. Threat appeals in health communication: Messages that elicit fear and enhance perceived efficacy positively impact on young male drivers. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojević, P.; Jovanović, D.; Lajunen, T. Influence of traffic enforcement on the attitudes and behavior of drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 52, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wundersitz, L.; Hutchinson, T.; Woolley, J. Best practice in road safety mass media campaigns: A literature review. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 5, 119–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzendorf, M.; Busch-Geertsema, A. The cycling boom in large German cities—Empirical evidence for successful cycling campaigns. Transp. Policy 2014, 36, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, R.; Bonham, J. More than a message: Producing cyclists through public safety advertising campaigns. In Cycling Futures; University of Adelaide Press: Adelaide, Australia, 2015; pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Gamble, T.; Walker, I.; Laketa, A. Bicycling campaigns promoting health versus campaigns promoting safety: A randomized controlled online study of “dangerization”. J. Transp. Health 2015, 2, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimano, A.; Piccini, M.P.; Passafaro, P.; Metastasio, R.; Chiarolanza, C.; Boison, A.; Costa, F. The bicycle and the dream of a sustainable city: An explorative comparison of the image of bicycles in the mass-media and the general public. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 30, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, R.M.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Mariñas, K.A.; Persada, S.F.; Nadlifatin, R. Exploring consumers” intention to use bikes and e-scooters during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: An extended theory of planned behavior approach with a consideration of pro-environmental identity. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoforou, Z.; de Bortoli, A.; Gioldasis, C.; Seidowsky, R. Who is using e-scooters and how? Evidence from Paris. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, E.; Bayles, E.; Daigle, L.; Mantine, D. Comparison of motor-vehicle involved e-scooter fatalities with other traffic fatalities. J. Saf. 2023, 84, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fundación Mapfre. Análisis de la Siniestralidad de Vehículos de Movilidad Personal 2023. Available online: https://documentacion.fundacionmapfre.org/documentacion/publico/es/media/group/1123576.do (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Nikiforiadis, A.; Paschalidis, E.; Stamatiadis, N.; Paloka, N.; Tsekoura, E.; Basbas, S. E-scooters and other mode trip chaining: Preferences and attitudes of university students. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2023, 170, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, E.; Yilmaz, V. Investigating the factors affecting electric scooter usage behavior with a proposed structural model. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2024, 56, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, D.J.; Hamilton, K. Predicting Undergraduates’ willingness to engage in dangerous e-scooter use behaviors. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 103, 500–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourfalatoun, J.; Ahmed, J.; y Miller, E.E. Shared Electric Scooter Users and Non-Users: Perceptions on Safety, Adoption and Risk. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taba, M.; Ayre, J.; Freeman, B.; McCaffery, K.; Bonner, C. COVID-19 messages targeting young people on social media: Content analysis of Australian health authority posts. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, A.; Valdez, D.; Walsh-Buhi, E.; Trueblood, J.S.; Lorenzo-Luaces, L.; Rutter, L.A.; Bollen, J. Misinformation and public health messaging in the early stages of the mpox outbreak: Mapping the Twitter narrative with deep learning. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, M.; Bunker, D. Social media trust: Fighting misinformation in the time of crisis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77, 102780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapliyal, K.; Thapliyal, M.; Thapliyal, D. Social media and health communication: A review of advantages, challenges, and best practices. In Emerging Technologies for Health Literacy and Medical Practice; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DRIEAT Île-de-France, «Quinzaine des Usagers Vulnérables (15 au 28 mai 2017): «Ne Prenez pas le Risque de voir la Mort en Face. Traversez en Respectant les feux de Signalisation!». Available online: https://www.drieat.ile-de-france.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/quinzaine-des-usagers-vulnerables-15-au-28-mai-a11468.html?lang=fr (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- SAAQ. Bone vs. Steel, You Don’t Stand a Chance. Cross at Intersections. 2024. Available online: https://www.adsoftheworld.com/campaigns/bone-vs-steel (accessed on 26 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).