Abstract

The teaching of environmental education must change to promote critical, sustainable, and reflective engagement with environmental problems. This study introduces a social-science question for primary education focused on pharmaceuticals in surface water. The aims of the paper are to evaluate the level of students’ performance in arguing their answers in relation to the reference answer; their use and interpretation of provided materials from which they draw the evidence to justify their arguments; and the type of solutions they propose in the framework of sustainability. This is carried out by analyzing the content of their written reports and the discourse during their group discussions. Statistical tests are also used to compare their individual and group performance. The results show that students perform at an intermediate level. They use text and video effectively but struggle with graphs and maps. Their proposed solutions are contextually appropriate and consider multiple perspectives. Notably, their performance is similar whether working individually or in groups. All in all, this pedagogical intervention in the framework of scientific practices and transformative environmental education supports the development of scientific thinking and sheds light on how students process information when addressing socio-environmental issues.

1. Introduction

We are facing an unprecedented environmental crisis. This is not surprising, as the planet has been warning us since the mid-20th century [1]. Despite this, humans have been intensively altering the planet for more than 200 years, transforming the landscape and making resource use unsustainable [2]. This situation requires citizens to be able to make critical decisions to solve environmental problems [3,4]. Therefore, it is urgent to start a process of change from education [5,6].

To this end, it is necessary to reorient the way environmental education (EE) is taught, since it does not respond to current educational needs [7,8,9,10]. In fact, historically, EE has only been associated with environmental literacy from a purely ecological perspective, leaving aside critical and ethical competencies [6,11,12,13,14]. Such competencies are fundamental for students to achieve a systemic understanding of problems and to make decisions in a critical and reasoned manner [12,15]. Therefore, the didactics of EE would be improved by introducing reflection or adding variables such as the scale of values or the social, cultural, and economic components [16]. In this way, we would speak of transformative environmental education (TEE) [14,17,18,19,20].

Thus, to work along the lines of TEE, it is necessary to include literacy, awareness and action in schools [21] in order to train citizens capable of identifying, understanding, problematizing, and arguing about environmental injustices and the consequences that these problematic issues have for society [22]. This should be transferred to the classroom through didactic proposals situated in real-life contexts that favor the development of multidimensional thinking, reasoned decision making, and critical thinking [14,23]. In this sense, argumentation occupies a relevant place among the scientific practices necessary for science education [24], known as argumentation, modeling, and inquiry. These play a fundamental role in the development of scientific literacy, which includes scientific knowledge, procedures, attitudes, and the transfer of learning to different contexts [25]. Thus, skills such as identifying and enumerating data in the face of problems are part of the construction of the individual and his or her discourse, and help to understand reality and act in it from a collective and critical perspective [22]. In fact, dialogical argumentation, in context and with real problems, contributes to the development of citizens’ critical thinking, to the extent that they become aware of the complexity of these issues and of all the dimensions involved [11,12,23], putting into practice skills useful for their personal, social, academic, and intellectual development [26].

A didactic tool to transfer these ideas into the classroom and to promote scientific thinking is socioscientific issues (SSIs) [27]. These are social, complex, and open questions with a scientific dimension, such as global warming, genetically modified organisms, or the use of pesticides in agriculture [28,29,30]. SSIs can also be controversial because they are interpreted from different perspectives and have multiple solutions depending on personal values and priorities [28,30,31]. Students are likely already familiar with various controversial ecosocial issues because they see them in the media or even talk about them in class [29], as many of the real problems affecting our society are related to science [16,23,27,32]. Thus, using this tool requires students to discuss and critically reflect on their values, consider other perspectives, and make decisions in an argumentative manner [29,30,33,34,35]. It also improves understanding of the nature of science [36] and inspires learners to take action [37].

Regarding the impact and behavioral changes that these interventions can generate, several studies have shown that environmental awareness decreases in adolescents [38,39], which does not mean that it is not useful at this stage, but that it is more difficult to cause changes in their behavior [40]. On the contrary, in the early stages, the impact is greater, and it is easier to create attitudes of change, so it is essential to implement interventions from early childhood education (ECE) and primary education (PE) [18,38,41]. In fact, several studies show that, contrary to what some believe due to the level of cognitive development of students, it is possible to work at this age with didactic tools that promote scientific thinking through the use of evidence and argumentation [42,43,44,45].

In particular, early EE research has been conducted on a variety of topics where students have demonstrated understanding, awareness, and even action. For example, in a study by Davis et al. [46] in Australia, 4-year-old children initiated investigations and actions in their kindergarten and community about water and water waste. In another study [47] conducted with 4- and 5-year-old children in the same country, it was found that they were concerned about pollution and the environment and showed environmental awareness regarding deforestation, global warming, and littering. Also, in the study conducted by Palmer and Suggate [48] in the United Kingdom, in which tropical rainforests, deforestation, endangered species, and polar environments were discussed, it was observed that 4-year-old children made statements about the effects of environmental changes on living beings and their habitat. In the same study, PE children formulated the same explanations, increasing their complexity and establishing relationships between habitats and their flora and fauna. Interventions have also been carried out, in which PE students in Cyprus demonstrated their ability to use evidence, generate arguments, and take a position on a socio-political and ethical issue. Specifically, how to decide which immigrants should be allowed to come and live in their country, based on either what they can contribute to the nation or on the basis of the poor quality of life in their country of origin [23]. In this way, the students had to position themselves before a current problem, that of immigration, from a variety of perspectives. However, even though scientific thinking can be worked on in ECE and PE, the presence of research framed within TEE at these ages is very scarce [7,49].

Therefore, it is necessary to design, implement, and evaluate the effectiveness of didactic proposals that allow the development of environmental and scientific competences in the framework of TEE in early stages (ECE and PE). In this sense, a real learning situation that is close to the students’ context has been designed: the presence of pharmaceuticals in water for human use from domestic wastewater, which endangers human and environmental health [50,51]. However, the problem is broader and not new, as it has been known for almost 50 years that pharmaceuticals are present in water bodies around the world [52,53,54]. Their presence alters the survival and reproduction of living organisms, which is evidence of the ineffectiveness of water treatment [55,56], as well as the high consumption and repeated discharge of pharmaceutical compounds [54]. Overall, the risk to environmental, animal, and human health (One Health) [57] from the presence of pharmaceuticals in surface waters is a SSI that relates to several Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including health and well-being (SDG 3), clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), responsible production and consumption (SDG 12), underwater life (SDG 14), and terrestrial ecosystem life (SDG 15).

The general objective of this research is to analyze how this proposal, within the framework of the TEE, promotes argumentation and scientific reasoning in 6th grade students. Specifically, the aim is to determine the level of students’ performance in arguing their answers in relation to the reference answer. We will also identify the types of materials from which they extract evidence and how they use them according to their level of understanding. In addition, the different solutions proposed by PE students when confronted with a SSI within the framework of TEE will be analyzed. Finally, the development of the activity will be compared in the individual and group phases.

To this end, the following research questions (RQ) will be addressed:

- RQ1. What is the level of performance of the students in solving this SSI, comparing their answers with the reference answer?

- RQ2. From what materials do they draw the evidence they use to formulate arguments, and how do they use it according to their level of understanding?

- RQ3. What solutions do the students propose to avoid the presence of pharmaceuticals in the river?

- RQ4. What are the differences in student performance when working individually and in groups?

For these research questions, we believe that although this type of educational practice is usually implemented at higher levels, such as secondary education and high school, primary-education students will still be able to solve the case, regardless of the level of performance. However, they may encounter greater difficulties with tasks that require extracting data from multiple sources and establishing connections between them (Hypothesis 1). Moreover, they might struggle with using and interpreting maps, as they are less familiar with this type of material. In contrast, working with texts is likely to be easier for them, given that textbooks are a predominant teaching resource (Hypothesis 2). Furthermore, we expect that students will be able to propose solutions to environmental problems (Hypothesis 3) and that, overall, collaborative group work will enhance their learning experience (Hypothesis 4).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

This study is framed within the multiple-case-study research method [58]. In this educational intervention, 24 students in the 6th grade of PE (11–12 years old) from a public school in the Community of Madrid participated. This center represents a medium-high socioeconomic level, as the average income per person of its local context exceeds the average income of the Community of Madrid. During the intervention, the students worked individually and in groups. When working in groups, the usual classroom work teams were maintained. For this reason, not all groups are made up of the same number of students. Thus, out of the six groups, there are four groups of 4 students, one group of 5 students, and one group of 3 students.

Regarding ethical considerations, student participation in this research was voluntary, with signed informed consent obtained. Anonymity has been ensured using numeric codes, and the analysis has focused solely on academic aspects, avoiding any personal or moral evaluations.

2.2. Activity: “Pharmaceuticals in the River?”

The designed activity has been validated by experts and consists of a case study based on a real-life situation that could serve as a plausible context for the students [51]. This activity shows the presence of pharmaceuticals in surface waters to promote a One Health approach in the classroom. Its design is based on the case method [59] and didactic transposition according to Guevara-Herrero et al. [60]. In addition, it incorporates didactic tools (storytelling, mediating questions, and data in different semiotic modalities) thanks to which students will be able to construct a reasoned answer to their questions.

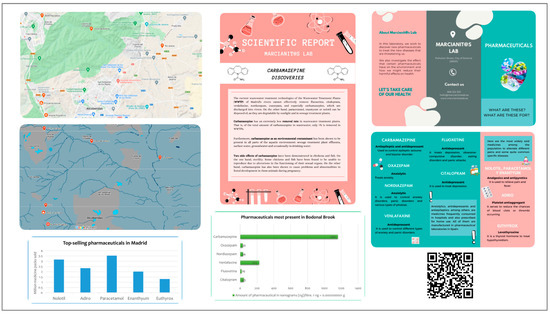

This activity entitled “Pharmaceuticals in the river?” has 4 phases. In the first phase, the case is presented to the students through a video of a scientist. He announces the alarming presence of pharmaceuticals in the Bodonal Stream (Community of Madrid) and asks the students to investigate and find out how and why it happened. In a second phase, the students are given a researcher’s notebook (Supplementary Materials) with questions to complete and a set of materials from which they must extract data and use them as evidence to argue their answers to be written in the notebook. The materials, which present the information in different semiotic modalities (Figure 1), are as follows:

Figure 1.

Activity materials given to PE students.

- A hydrographic map and a satellite map of the area. Students are asked to locate themselves on the map and identify the source of the river’s pharmaceuticals.

- A bar chart of the pharmaceuticals most present in the Bodonal Stream and another of the pharmaceuticals most sold in the Community of Madrid. Both graphs are useful to know what is polluting the river and in what quantity, and to relate why the most-sold pharmaceuticals are not the most present in the river.

- An informative trifold leaflet on the pharmaceuticals present in the sample area and the most sold: what they are, what they are for, where they are consumed, etc. This material can be used to identify the pharmaceuticals prescribed to treat chronic diseases related to mental health.

- A video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hi2ilunFSWc, accessed on 1 October 2024) explaining what a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) is and how it works.

- A scientific report detailing the findings on carbamazepine as an environmental pollutant: the side effects of carbamazepine, WWTP disposal capacity, etc.

After analyzing all the materials, students must individually answer the questions in their notebooks: “According to what you read and saw, what is the river polluted with?” (Q1); “According to what you have read and seen, where do the medicines in the river come from?” (Q2); “What diseases do these medicines treat?” (Q3); “If the medicines most abundant in the Bodonal River are not the most sold, how and why do they end up in the river in such quantity?” (Q4); “Is it harmful for medicines to be in the river?” (Q5); “Would it be better to take medicines or not? Why?” (Q6); and “What solutions can you think of to prevent so many medicines from entering the river? (Q7). A reference answer for each of these questions is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

In a third phase of the activity, students must work in groups and solve the case again. They have to discuss their individual answers and write a single group answer to each question. Finally, in the fourth phase, a large group debriefing will take place in which students will be guided to the complete reference answer of the activity (Supplementary Materials).

2.3. Data Analysis

In this study, a qualitative analysis of the content of the students’ written responses [61] and an analysis of the students’ discourse when solving the case in groups [62] were carried out by listening to and interpreting the data. Their individual written responses and their written and oral group responses were processed in order to know (a) the level of performance that students achieve when solving the activity individually and in groups, according to their approach to the reference answer; (b) the number and provenance of the evidence they draw from the materials to argue their answers; and (c) the type of solutions they propose.

For Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, and Q6, a deductive categorization was applied (Table 1), defining five performance levels in terms of proximity to the reference answer and six categories to determine the origin of the evidence used: report, graphs, maps, trifold leaflet, initial video, and QR video. For Q7, an inductive categorization was applied, establishing five categories according to the type of solutions proposed by the students. After the categorization, the absolute frequencies (Q1 to Q6) and the relative frequencies (Q7) were calculated.

Table 1.

Analysis of students’ performance levels by question.

2.3.1. Categorization of the Use of Materials

To analyze the level of comprehension of textual materials (report and trifold leaflet), the taxonomy of Barret [63] was used, which is currently used for different assessments such as PISA or PIRLS [64]:

- Level 1. Reading comprehension: recognizing explicit information in text, identifying dates.

- Level 2. Reorganize information: establish logical relationships between ideas, synthesize, classify.

- Level 3. Inferential or interpretive: integrating new implicit meanings from the text.

- Level 4. Critical or evaluative judgment: reflecting critically, comparing the ideas in the text based on personal experience or other external sources of authority.

- Level 5. Reading evaluation: evaluating the language, the style of the text, and the sensations or effects of the text on the reader.

The classic scheme proposed by Curcio [65] was used to classify the type of student responses when working with graphs:

- Level 1. Read the data: no data interpretation; the answer may be a literal copy of the graph title or axis.

- Level 2. Reading between the data: how to interpret the data, how to make comparisons between the values.

- Level 3. Reading beyond the data: this requires inference and extrapolation of data, linking the interpretation of the graph to students’ prior knowledge or concepts present in the graph.

- Level 4. Reading behind the data: it involves a critical analysis of the graph and the quality of the data, linking the values in the graph to context.

2.3.2. Individual and Group Performance Analysis

To compare the individual and group performance of the study participants, the mean values of the group performance level from Q1 to Q6 were statistically compared with the mean values obtained for the individual cases. A non-parametric statistical analysis of means comparison (Mann–Whitney U test, p ≤ 0.05) was performed on these data. In Q7, data were analyzed using the non-parametric test of χ2 (chi-square test, p ≤ 0.05). In all cases, descriptive and inferential analyses were performed using statistical tools from Microsoft Excel TM and IBM® SPSS® Statistics 19 2010.

3. Results and Discussion

The overall average of the students in the activity is 3.44. As shown in Table 1, there is one high level (level 5) and two lower levels (1: zero and 2: low). This suggests that the average performance of the activity falls within the intermediate range (levels 3–4), confirming Hypothesis 1.

3.1. Analysis of Student Performance Level and Use of Materials

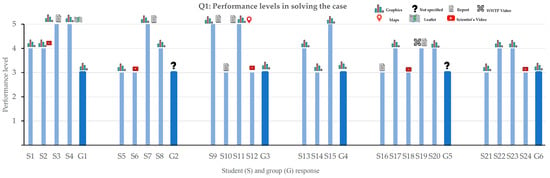

In the individual answers to Q1 (Figure 2), 9 students achieved a medium-low level, 9 a medium-high level, and 6 a high level when comparing their answers with the reference answer. When working in groups, they all reached a medium-low level because they gave a less detailed answer (Table 1, Q1), mentioning only that the river is polluted by some pharmaceuticals without listing them all and without highlighting carbamazepine.

Figure 2.

Performance levels and materials from which evidence is taken for Q1.

Regarding the origin of the evidence used in the individual work (Figure 2), 11 students only used graphs, 6 supplemented them with other materials, 4 only used the scientist’s video, and 3 used other materials. On the other hand, 4 groups used graphs and 2 did not specify which material they had used. To reach the highest level of performance, it is sufficient to use the graphs, and the scientist’s video can be used complement the information. In the other materials they used (trifold leaflet or report), the names of the pharmaceuticals appear, but not the data necessary to give a high-level answer, including which pharmaceuticals are in the river and in what quantities. Therefore, all these results indicate that more than half of the students used the graphs correctly.

According to the taxonomy of Curcio [65] for the comprehension of the graphs, six high-level students respond at level 2 (read between the data) because the question asks them to know what pollutes the river and they must choose the bar graph that gives them this information and compare the values of each pharmaceutical. The rest of the students gave a level 1 answer (reading the data), because they mentioned some (nine medium-low students) or all (nine medium-high students) of the pharmaceuticals that appear on the “Y” axis of the graph. The students did not seem to have had any difficulty with this question. This may be because graphs (especially bar graphs) and activities that require reading the data and reading between the data (levels 1 and 2) are very present in Spanish textbooks [66]. This means that students are used to reading graphs literally and making comparisons, while they tend to have more difficulty making inferences or critically evaluating them [67].

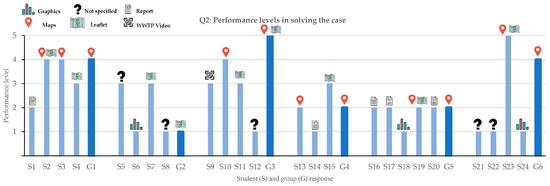

Regarding Q2 (Figure 3), 8 students show a null performance level, 6 a low level, 6 others a medium-low level, 3 a medium-high level, and 1 student a high level. When working in groups, 1 group scores zero, 2 low, 2 medium-high, and 1 high. This question is the one in which the students show the lowest level of performance, as the vast majority do not know how to extract information from a map. This is evidence of the problems that PE students have in interpreting this type of material and achieving a good level of performance. In order to understand why students have so many difficulties in using maps appropriately, it is necessary to review their presence in the Spanish curriculum and how they are used in the classroom. For example, the relevance of maps in national and regional educational legislation is insufficient [68]. In the third cycle of the PE, the contents are defined as “the location of the relief units on the map of Spain”, “the location of the rivers of the Iberian Peninsula on the map of Spain, their sources, mouths and main tributaries”, and “graphic, visual and cartographic representation using analogue and digital resources”. Thus, only the memorization of the names and location of the rivers on the map is required, but not the interpretation and use of maps in everyday situations. Similarly, the standardized regional assessment tests (Essential Skills and Competencies Test) do not include maps. These tests assess four competences: linguistics in Spanish, linguistics in English, mathematics, and science and technology. None of the tests administered since 2015 have included maps in the science and technology competence. Armas-Quintá et al. [69] point out that this situation leads to a transmissive teaching model that prevents the critical and reflective teaching of geography, since the curricula aim to have students name, locate, or define. They also point out that maps are only used in the classroom to confirm or illustrate knowledge. To solve this problem, we currently have digital tools (Google Earth, Google Maps, Google Street View) and it is advisable to use them, as they allow for the development of critical and creative thinking, and different layers of geographical information can be combined to improve the understanding of physical and human factors [69]. Therefore, in this activity, two maps of the same geographical area are presented, one with a satellite view and the other with a hydrographic view.

Figure 3.

Performance levels and materials from which evidence for Q2 is drawn.

Moreover, knowing how to use maps is essential for understanding the world around us and interpreting all kinds of spatial information, from any point in the world to the place where each individual lives [70,71]. However, little work has been carried out in classrooms, and it is also a rare topic in educational research [71]. There are exceptions, such as the study by Bugdayci and Selvi [70] in Turkey, which identified the need for proper map work in classrooms and initiated a project to design an atlas for PE that includes different types of maps.

It is true that children often have difficulties in reading and interpreting maps, and for this reason they should be familiarized with maps and use them for orientation throughout the PE phase. According to Græsli and Lien [72], they have the ability to work with all types of maps, but due to their cognitive development, it would be advisable to start in the early grades with perspective maps (more intuitive representations of the real world, with concrete, tangible, and recognizable details) and progress until they are able to work with symbolic maps (constructions of reality that require the ability to abstract and decode symbols and information). Therefore, it would be advisable to include this type of representation from an early age (from 5 years) [71,72]. In the case of our activity, the two maps presented are symbolic, as children should be able to understand them without much difficulty in the last few years of PE.

To achieve a high level of performance in Q2 (Table 1, Q2), one must use the maps and the trifold leaflet. Figure 3 shows that only 3 students used data from both materials as evidence, 3 students used maps, 4 students used trifold leaflets, 9 students used other materials (of which only the report or the video can give them useful information) and 5 students did not specify which material they use. In terms of the use of materials, when students worked in groups, materials that were not useful were discarded. Thus, 5 groups used maps and 1 group the trifold leaflet, although in no case were they able to integrate these two materials, which is necessary to achieve the maximum level of performance in relation to the reference answer. Even in some cases, the students who used the map and the trifold leaflet (S2, S19) did not reach a high level because they only looked at the map data and ignored the relevant information in the trifold leaflet, probably because they made decisions too quickly and did not read the whole text carefully [11]. Nevertheless, we observe that working in groups improves the choice of material (map) and its interpretation. According to Cîineanu et al. [73], this may be due to the fact that in a group they can exchange ideas, identify the elements of the map better, and achieve a better understanding of the material than when working individually.

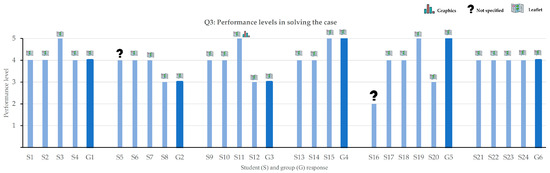

For Q3 (Figure 4), more than half of the students reached the medium-high level, four were at the lower levels, and another four at a high level. According to Barret’s taxonomy [63], these four students (high level) were at level 2 (reorganizing information) in terms of the majority of their use of the trifold leaflet, because they are able to interpret the information, synthesize it, and create their own discourse in which they understand that all illnesses are related to mental health (Table 1, Q3). On the contrary, 16 students (intermediate level) would be at level 1 (literal comprehension) because they copied the information about the pharmaceuticals in the river that are used to treat some diseases. This reflects the tendency to copy the information literally, as the activities in the books usually do not encourage interpretation, but rather require a textual reproduction of the content [74]. In contrast, two of the six groups reached a medium-low level, two reached a medium-high level, and another two reached a high level.

Figure 4.

Performance levels and materials from which evidence for Q3 is drawn.

To reach a high level, it is enough to use the trifold leaflet. For this question, the students demonstrated a strong ability to select the appropriate material, since 21 students used the trifold leaflet, 1 also combined it with the graph, and 2 students did not specify which data they used (Figure 4). All the groups used the trifold leaflet in the same way. The students did not have any difficulties in choosing the trifold leaflet and selecting the information, which could be due to the fact that they tend to prefer visual and synthesized data [11]. In addition, it is an expository text, and students are usually used to working with them in the social and natural sciences, as they are the most-used texts in these areas, because they deal with topics of interest for understanding the society in which we live [64].

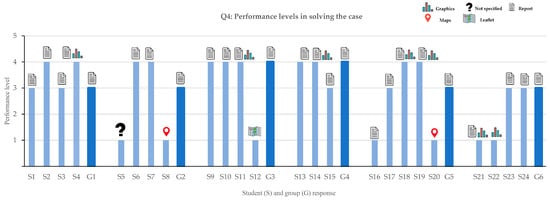

In the individual responses to Q4 (Figure 5), 11 students scored at a medium-high level, 6 at a medium-low level, and 7 at a null level. When working in groups, 2 groups reached a medium-high level and 4 groups reach a medium-low level, with zero responses at a null level. In no case was a high level of performance reached, where the answer should include the relationship between the most- and least-sold pharmaceuticals, how they are eliminated, and specify that the most present pharmaceuticals are used for chronic treatments, as they are constantly discharged (Table 1, Q4). According to Barret’s taxonomy of levels [63], this high-level response requires a reading comprehension level of 3 (inferential or interpretive). On the other hand, the highest level achieved by the students (individually and in groups) is medium-high, giving a text comprehension response at level 2 (reorganizing information), as they combined the information by establishing relationships between the most- and least-sold pharmaceuticals. Similarly, six students (medium-low level) reach level 1 (literal comprehension), identifying only some data from the text (Table 1, Q4).

Figure 5.

Performance levels and materials from which evidence for Q4 is drawn.

With regard to the origin of the evidence used in the individual work (Figure 5), 6 students used two materials (report and graphs), 17 used only one (the report in all cases, except for two students who used the maps and one who used the trifold leaflet), and 1 did not specify. Both the omission of data and their inadequate use show a performance level of zero. When working in groups, in all cases they use only one source of information (the report). However, they were expected to use the graphs and the report in order to respond with a high level of performance, so students seem to have difficulties in integrating evidence from different sources. We can also interpret that they prefer texts to graphs, possibly because of their regular use [64] and the ease of their analysis and interpretation compared to graphs. In fact, according to Curcio’s taxonomy [65], the 11 students who used graphs in their answer (medium-high) reached level 2 (read between data) as they compared the most- and least-sold pharmaceuticals (Table 1, Q4). And, as mentioned above, no student performed at a high level on this question, so the student body was not able to perform a level 3 graph comprehension (read beyond the data).

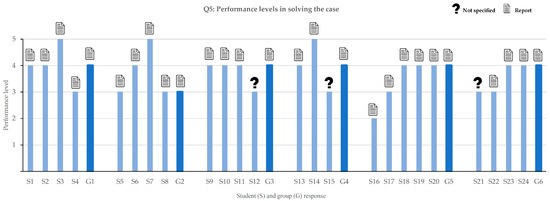

For Q5, 12 students were at a medium-high level, 8 at a medium-low level, only 3 at a high level, and 1 at a low level. All groups were at a medium-high level, except for 1 group at a medium-low level (Figure 6). Thus, half of the students (medium-high level) were able to take a position on whether the presence of pharmaceuticals in the river is harmful or not and to justify it with evidence, showing a level of reading comprehension of 2 (reorganizing information) according to Barret [63]. On the other hand, nine students (medium-low and low level) did not justify their answers, reaching level 1 (literal comprehension). This fact is not surprising since, as Peña-García [75] mentions, more work is carried out in classrooms on identifying information in descriptions and making summaries, and less on arguing about a text. It is worth noting that three students (high level) were capable of addressing the One Health approach. An example of this is shown in this extract: “Yes, one of the causes why it is harmful is to all living things that live in or near the river. Because if they ingest it, it could be very harmful to them [animal and environmental health]. It would not be harmful to us to drink because we do not usually drink from that water. But on the other hand, that water is used for irrigation. And those plants could die, or worse, they could get infected, and we would eat those plants [environmental and human health]” (S7). In this way, a level 4 understanding of the text (critical or evaluative judgment) is achieved, since they reflect critically on the complexity of the environmental problem from a vision that is close to the concept of One Health.

Figure 6.

Performance levels and materials from which the evidence for the Q5 is drawn.

Therefore, some constructed a complete vision of One Health. However, others did not reach it, because to fully assimilate this concept it is essential to address the three dimensions in an integrated manner and not separately (animal–human health, environmental–human health, animal–environmental health) [76]. In any case, this activity on the presence of pharmaceuticals in waters does seem to promote the systemic vision and the acquisition of an environmental competence that can prepare students to face environmental challenges in a critical and well-reasoned way. With this type of didactic proposal, we believe we are moving closer to a TEE [14,18,19,20,60,76].

In this case, all students except three have extracted the evidence from the report, which is the material that allows them to reach a high level (Table 1, Q5). Similarly, all the groups used this material (Figure 6). Although they made a very good choice in terms of material, this did not allow them to reach the maximum level of performance. As with the use of the trifold leaflet in Q2, the students did not read the texts carefully and therefore did not extract all the information necessary to argue their answer.

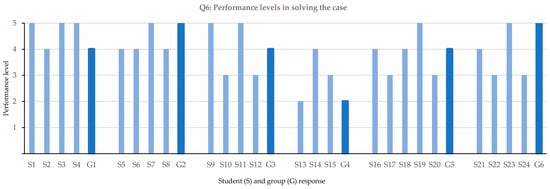

Q6 does not require students to use data to justify their answers because it is a social-science controversy. Students have to take a position on whether it is better to take medication or not and why. This activity is designed to facilitate the students’ ability to reflect on scientific concepts without having any prior knowledge of them, using only the knowledge they have learned during the activity [11,60].

One student achieved a low level, seven a medium-low level, eight a medium-high level, and another eight a high level (Figure 7). Thus, 16 students were able to give a reasoned answer and 8 of them included in their answers the ideas of avoiding self-medication, the need for medical prescription, and/or responsible consumption (Table 1, Q6). When working in groups, one group achieved a low level, three groups an intermediate level, and two groups a high level.

Figure 7.

Performance levels and materials from which evidence for Q6 is derived.

Students were able to critically discuss this question on the basis of what they had learned. Therefore, in our view, the teaching of experimental sciences should focus on working on scientific practices from an early age so that students can connect science to everyday life [25,77,78] and apply scientific knowledge, attitudes, and skills to realistic contexts [23,79], as was achieved in this activity through argumentation.

In Q7 (Figure 8), all students proposed individual solutions (sometimes more than one), mainly type A “pharmaceutical design and WWTP” (35.14%) and type B “responsible use” (24.32%). To a lesser extent, solutions of type C “political-legislative measures” (8.11%) and numerous solutions of type D “not in line with content or generic” (32.43%) also appear (Table 1, Q7). When working in groups, type A (50.0%), B (33.33%), and C (8.33%) solutions increased, while type D solutions decreased (8.33%). Although group work seemed to favor the decrease in type D solutions and the increase in proposed solutions, no statistically significant differences were found (chi-square test, χ2, p ≤ 0.05). Nevertheless, in this way, students included dimensions in the discussion of solutions that they had not previously considered [23].

Figure 8.

Relative frequencies of types of solutions proposed by students working individually and in groups.

Therefore, we see that all PE students participating in the study were able to propose solutions to controversial environmental problems, confirming Hypothesis 3. However, they usually did not assess the consequences of the impacts caused by the proposed solutions, which are solutions constructed from a simplistic view of the problem [23,35].

Moreover, we can see that they dealt with different perspectives in their solutions [35,80], mainly scientific (S5: ’Try to improve the purifiers so that the urine is filtered properly’; type A solution) and ethical (S9: ’Reduce the consumption of pharmaceuticals, do not self-medicate and only take the absolutely necessary pharmaceuticals prescribed by the doctor’; type B solution), but also, although to a lesser extent, social and political (S23: ’Ban this type of drug’; type C solution). In fact, according to Esquivel-Martín et al. [11], secondary-school students also considered scientific and economic solutions to avoid the toxic risk caused by pesticides, but not ethical or political solutions, as is the case here in PE. Similarly, when solving an SSI on the production and consumption of avocados in Spain, Pre-service teachers also focus more on the health and environmental perspectives and less on the ethical perspective [12].

3.2. Analysis of the Level of Individual and Group Performance

An analysis was conducted to determine if there were differences in the level of performance achieved individually and in groups, as group or collaborative work has traditionally been associated with improved student performance [81,82]. Furthermore, collaborative environments tend to enhance cognitive, social, and metacognitive skills as students engage in dialogue, share ideas, and make collective decisions [83,84]. In particular, according to Peña-García [75], working on a text in a group improves reading comprehension and synthesis of ideas.

For this analysis, a comparison of individual and group performance levels (Table 1) was made in two different ways: 1) by analyzing the level of individual and group performance presented by each of the six groups in the different questions, and 2) by analyzing the overall level of individual and group performance per question.

Overall, with regard to how each of the groups behaved individually and as a group during the development of the whole activity, there are no significant differences in any case (Table 2).

Table 2.

An analysis of the difference between individual and group performance by group for all questions (Mann–Whitney U test, p ≤ 0.05).

On the other hand, Table 3 shows no significant differences between individual and group performance for questions Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, and Q6 (Mann–Whitney U test, p ≤ 0.05). This suggests that students’ performance is not influenced by whether they work individually or in groups, thus refuting Hypothesis 4. In Q1, however, we found significant differences (Mann–Witney U test, p ≤ 0.05). In this question, working in groups limits or even impairs students’ performance. We have observed that when they work individually, they give more detailed answers, while in a group they answer superficially, without giving details about the types of pharmaceuticals that pollute the river and in what quantities. This may depend on many other factors, such as the nature of the question, the materials used, the social interactions within each group, or the role of each member within the group. Even the sense of belonging to social groups and the desire to feel accepted can guide the decision-making process [32], so this aspect can also influence the outcomes of the activity. This was seen in some cases where for example, G6 did not accept the suggestions of one of its members (S23), even though they were correct:

Table 3.

An analysis of the difference between individual and group performance on each question. An asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences (Mann–Whitney U test, p ≤ 0.05).

- − S21: “Question number six. So… Would it be better not to take medicines? I don’t think it would be better to take medicines because they heal the problems we have, but we should try not to throw them into rivers or sewers to avoid contamination”.

- − S23: “The problem is that with the feces… it is expelled and some of the medicine goes away. I think it would be best to take medication only when it is really necessary and not just for any reason”.

- − S24: “So we say no because it helps us avoid disease, but we shouldn’t throw it in the rivers either”.

- − S23: “But, but… you have to try to consume them properly. You have to consume them a little […] You have to consume them a little. You have to use them a little bit, OK?”.

- − S22: “Mmm, no, no”.

- − S23: “And it doesn’t make any sense, because the sewage […] When we expel the feces, some of the medicine comes out”.

- − S21: “Yes, but only part of it comes out and not all of it. In the meantime, there are people who take it and throw it away. So, I think the correct answer is…”.

- − S23: “No, I think… We can’t be so stupid as to flush the medicine down the toilet”.

- − S21: “No, we should not stop taking medicines because they help us avoid disease, but we should take them correctly”.

4. Conclusions

Based on our results, PE students are able to deal with practical cases based on a SSI and solve them at intermediate levels of performance, using different materials and proposing solutions considering different perspectives such as scientific, ethical, social, or political. In addition, some students were able to link the three dimensions of health (One Health). Thus, through this proposal, they begin to interpret environmental and social challenges from a systemic and critical point of view.

Furthermore, this study has allowed us to conclude that in this activity the level of performance of the students does not improve when they work in groups. We can understand this situation because if there are many students who individually do not know how to interpret information on a map, graph, or text, they will not be able to do so in a group when they are in the same group, even if they have had previous experience in cooperative learning, so it is impossible for them to improve their learning. On the other hand, if we can get a greater number of individual students to improve their performance in handling the materials, there is a greater chance that there will be an exchange of knowledge in the same group, and this will lead to an improvement in learning for all.

It is also important to note that students have used all the materials, but in different ways. The materials they use the most are texts and videos, followed by graphs, and finally maps, confirming Hypothesis 2. They have no problems working with texts, as they only have to read the information, try to understand it (even literally) and, if necessary, reorganize it. However, they still have difficulties in selecting and synthesizing information. A similar situation occurs with graphs, since, although it is a visual and apparently attractive material, students do not manage to infer or extrapolate data, but only make comparisons or copy data from the graph, showing a lack of mastery in the handling of this material. Finally, we can affirm that maps are the material which causes the most problems for PE students in extracting information. In this respect, they have difficulties in their use and interpretation because they are not used to working with them, and if they do so, it is by rote and only in some aspects of the social sciences (rivers, mountains, mountain ranges, capitals, countries, regions, etc.). This in turn shows the fragmentation of the teaching of EE, making it difficult to incorporate specific tools to develop an interdisciplinary vision of EE. Thus, it is evident that students establish the order of preference of the materials they use according to their skills in understanding and interpreting them.

This leads us to reflect on the need to work with maps and graphs in the classroom from an early age, so that students reach higher levels of understanding and are able to extract and interpret information from any type of material. In this way, they will be able to face current socio-environmental and other everyday challenges with less difficulty, as they will be able to critically analyze any type of information and propose solutions in a reasoned way.

The results presented in this article are the first data obtained from an educational intervention that is part of a larger teaching sequence. On the basis of this intervention, we have been able to find out how a group of PE students deals with a SSI on environmental health, which contributes to the development of their environmental competences. In this sense, our work contributes something unusual to the frame of reference of studies analyzing students’ performance in relation to scientific practices: it focuses on a group of PE students. However, it is too early to generalize these results, and it would be interesting for future research to analyze how PE students in other educational contexts solve SSI individually and in groups, how they use the materials, and what solutions they propose. These and other findings would be key to contributing to the improvement of One Health teaching in the context of EE with a transformative perspective.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17041618/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.F.-H., J.M.P.-M. and I.G.-H.; methodology, N.F.-H., J.M.P.-M. and T.E.-M.; validation, J.M.P.-M., I.G.-H. and T.E.-M.; formal analysis, N.F.-H. and J.M.P.-M.; investigation, N.F.-H., J.M.P.-M. and I.G.-H.; resources, N.F.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, N.F.-H.; writing—review and editing, N.F.-H., J.M.P.-M., I.G.-H. and T.E.-M.; supervision, J.M.P.-M.; project administration, N.F.-H.; funding acquisition, J.M.P.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades [N.F.-H] predoctoral research contract (FPU22/02563). This research was supported by the III Edition of the Programme for the Promotion of Knowledge Transfer of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (FUAM, 0375/2022, 465059).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (protocol code CEI-137-2954, and date of approval 14 March 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to express their sincere thanks to both the students and teachers who participated in the study and to Raquel Mínguez Castellano for the technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, A.Y.; Wiedmann, T.O. Humanity’s unsustainable environmental footprint. Science 2014, 344, 1114–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossér, U.; Lundin, M.; Lindahl, M.; Linder, C. Challenges faced by teachers implementing socio-scientific issues as core elements in their classroom practices. Eur. J. Sci. Math. Ed. 2015, 3, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapp, W.B.; Bennett, D.; Bryan, W.; Fulton, J.; Mac Gregor, J.; Nowak, P.; Swan, J.; Wall, R.; Havlick, S. The concept of environmental education. Environ. Educ. 1969, 1, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erduran, S. Science Education in the Era of a Pandemic. Sci. Educ. 2020, 29, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Raath, S.; Lazzarini, B.; Vargas, V.R.; de Souza, L.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Haddad, R.; Klavins, M.; Orlovic, V.L. The role of transformation in learning and education for sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Herrero, I.; Bravo-Torija, B.; Pérez-Martín, J.M. Educational Practice in Education for Environmental Justice: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Esquivel-Martín, T.; Guevara-Herrero, I. En busca de la dimensión abandonada: La Didáctica de la Educación Ambiental. In Educación Ambiental de Maestros Para Maestros; Pérez-Martín, J.M., Esquivel-Martín, T., Guevara-Herrero, I., Eds.; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2022; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.; Dillon, J.; Ardoin, N.; Ferreira, J.A. Scientists’ warnings and the need to reimagine, recreate, and restore environmental education. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, N.; Adger, W.N.; Agnolucci, P.; Blackstock, J.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Chaytor, S.; Colbourn, T.; Collins, M.; Cooper, A.; et al. Health and climate change: Policy responses to protect public health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1861–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Martín, T.; Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Bravo-Torija, B. Does Pollution Only Affect Human Health? A Scenario for Argumentation in the Framework of One Health Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Herrero, I. Is Consuming Avocados Equally Sustainable Worldwide? An Activity to Promote Eco-Social Education from Science Education. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvé, L. La educación ambiental entre la modernidad y la posmodernidad: En busca de un marco de referencia educativo integrador. Tópicos 1999, 1, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Valladares, L. Scientific literacy and social transformation. Sci. Educ. 2021, 30, 557–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siarova, H.; Sternadel, D.; Szőnyi, E. Research for CULT Committee—Science and Scientific Literacy as an Educational Challenge. In Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, J.S.C. Shifting the teaching beliefs of preservice science teachers about socioscientific issues in a teacher education course. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2022, 20, 659–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara-Herrero, I.; Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Bravo-Torija, B. Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on educational research on Environmental Education. Rev. Eureka Ensen. Divulg. Cienc. 2023, 20, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Rial, M.A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, U.; Varela-Losada, M.; Vega-Marcote, P. ¿Influyen las características personales del profesorado en formación en sus actitudes hacia una educación ambiental transformadora? Pensam. Educ. Rev. Inv. Latinoam. 2020, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogren, A.; Gericke, N.; Scherp, H.A. Whole school approaches to education for sustainable development: A model that links to school improvement. Environ. Educ. 2019, 25, 508–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ariza, M.; Quesada, A.; Estepa, A. Promoting critical thinking through mathematics and science teacher education: The case of argumentation and graphs interpretation about climate change. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2021, 47, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faize, F.A.; Akhtar, M. Addressing environmental knowledge and environmental attitude in undergraduate students through scientific argumentation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, A.C.; Do Nascimiento, A.L.; De Castro, R.G.; Motokane, M.T.; Reis, P. Biodiversity and Citizenship in an Argumentative Socioscientific Process. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iordanou, K. Supporting strategic and meta-strategic development of argument skill: The role of reflection. Metacognition Learn. 2022, 17, 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. Next Generation Science Standards: For States, by States; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2025 Science Framework (Draft); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://pisa-framework.oecd.org/science-2025/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- De Pro, A. Enseñar procedimientos: Por qué y para qué. Alambique: Didáctica de las Ciencias Experimentales; Dialnet: Logrono, Spain, 2013; Volume 73, pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bächtold, M.; Pallarès, G.; De Checchi, K.; Munier, V. Combining debates and reflective activities to develop students’ argumentation on socioscientific issues. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2022, 60, 761–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak, B.; Topçu, M.S. Integrating socioscientific issues and model-based learning to decide on a local issue: The white butterfly unit. Sci. Act. 2023, 60, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaver, L.T.; Walma van der Molen, J.H.; Sins, P.H.; Guérin, L.J. Students’ engagement with Socioscientific issues: Use of sources of knowledge and attitudes. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2023, 60, 1125–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, D.L.; Herman, B.C.; Sadler, T.D. New directions in socioscientific issues research. Discip. Interdiscip. Sci. Educ. Res. 2019, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T.D. Informal reasoning regarding socioscientific issues: A critical review of research. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2004, 41, 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.D.; Ahearn, K.A.; Allen, B.A.; Anand, D.M.; Coppens, A.D.; Aikens, M.L. The decision is in the details: Justifying decisions about socioscientific issues. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2023, 60, 2147–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evagorou, M.; Dillon, J. Introduction: Socio-scientific Issues as Promoting Responsible Citizenship and the Relevance of Science. In Science Teacher Education for Responsible Citizenship. Contemporary Trends and Issues in Science Education; Evagorou, M., Nielsen, J.A., Dillon, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, B.C.; Sadler, T.D.; Zeidler, D.L.; Newton, M.H. A Socioscientific Issues Approach to Environmental Education. In International Perspectives on the Theory and Practice of Environmental Education: A Reader; Reis, G., Scott, J., Eds.; Environmental Discourses in Science Education Series; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- List, A. Demonstrating the effectiveness of two scaffolds for fostering students’ domain perspective reasoning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 38, 1343–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J. A practice-based approach to learning nature of science through socioscientific issues. Res. Sci. Educ. 2020, 52, 259–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-Y.; Liu, S.-Y. Developing Students’ Action Competence for a Sustainable Future: A Review of Educational Research. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, D.; Gericke, N. The adolescent dip in students’ sustainability consciousness. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wetering, J.; Leijten, P.; Spitzer, J.; Thomaes, S. Does environmental education benefit environmental outcomes in children and adolescents? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D.S.; Dahl, R.E.; Dweck, C.S. Why Interventions to Influence Adolescent Behavior Often Fail but Could Succeed. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 13, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. The effects of children’s age and sex on acquiring pro-environmental attitudes through environmental education. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytelman, A.; Iordanou, K.; Constantinou, C.P. Prior. Knowledge, Epistemic Beliefs and Socio-scientific Topic Context as Predictors of the Diversity of Arguments on Socio-scientific Issues. In Current Research in Biology Education. Contributions from Biology Education Research; Korfiatis, K., Grace, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshach, H. Science for young children: A New Frontier for Science Education. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2011, 20, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, M.; Luzuriaga, M.; Taylor, I.; Jarvis, D.; Dominguez Prost, E.; Podestá, M.E. The use of questions in early years science: A case study in Argentine preschools. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2019, 27, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo-Molinero, M.; Salvadó-Belart, Z. Fostering Kindergarteners’ Scientific Reasoning in Vulnerable Settings Through Dialogic Inquiry-Based Learning. In Fostering Inclusion in Education; Postiglione, E., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Rowntree, N.; Gibson, M.; Pratt, R.; Eglington, A. Creating a culture of sustainability: From project to integrated education for sustainability at Campus Kindergarten. In Handbook of Sustainability Research; Filho, W.L., Ed.; Peter Lang Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 563–594. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, D.; Holden, C. Remembering the future: What do children think? Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.; Suggate, J. The development of children’s understanding of distant places and environmental issues: Report of a UK longitudinal study of the development of ideas between the ages of 4 and 10 years. Res. Pap. Educ. 2004, 19, 205–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Revealing the research ‘hole’ of early childhood education for sustainability: A preliminary survey of the literature. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.G.; Catalá, M.; Maroto, R.R.; Gil, J.L.R.; de Miguel, Á.G.; Valcárcel, Y. Pollution by psychoactive pharmaceuticals in the Rivers of Madrid metropolitan area (Spain). Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcárcel, Y.; Alonso, S.G.; Rodríguez-Gil, J.L.; Gil, A.; Catalá, M. Detection of pharmaceutically active compounds in the rivers and tap water of the Madrid Region (Spain) and potential ecotoxicological risk. Chemosphere 2011, 84, 1336–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daughton, C.G.; Ternes, T.A. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: Agents of subtle change? Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 907–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hignite, C.; Azarnoff, D.L. Drugs and Drug Metabolites as Environmental Contaminants: Chlorophenoxyisobutyrate and Salicyclic Acid in Sewage Water Effluent. Life Sci. 1977, 20, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, J.L.; Boxall, A.B.; Kolpin, D.W.; Leung, K.M.; Lai, R.W.; Galbán-Malagón, C.; Adell, A.D.; Mondon, J.; Metian, M.; Marchant, R.A.; et al. Pharmaceutical pollution of the world’s rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113947119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domènech, X.; Ribera, M.; Peral, J. Assessment of Pharmaceuticals Fate in a Model Environment. Water. Air. Soil. Pollut. 2011, 218, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A. Occurrence of drugs in German sewage treatment plants and rivers. Water Res. 1998, 32, 3245–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuasi, J.H.; Lucas, T.; Horton, R.; Winkler, A.S. Reconnecting for our future: The Lancet One Health Commission. Lancet 2020, 395, 1469–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herreid, C.F. Case study teaching. In New Directions for Teaching and Learning; William Buskist, W., Groccia, J.E., Eds.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Herrero, I.; Esquivel-Martín, T.; Fernández-Huetos, N.; Pérez-Martín, J.M. Towards Transformative Environmental Education: Effective Activities for Primary Education. In Interdisciplinary Approach to Fostering Change in Schools; Güneş, A.M., Yünkül, E., Eds.; IGI-Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 70–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, J.P. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method, 4th ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, T.C. Taxonomy of cognitive and affective dimensions of reading comprehension. In Innovation and Change in Reading Instruction; Robinson, H.M., Ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968; pp. 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamedi-Amaruch, A.; Rico-Martín, A.M. Assessment of reading comprehension in primary education: Reading processes and texts [Evaluación de la comprensión lectora en educación primaria: Procesos lectores y textos]. Leng. Mod. 2020, 55, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Curcio, F.R. Developing Graph Comprehension; NCTM: Reston, VA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Levicoy, D.; Batanero, C.; Arteaga, P.; Gea, M.M. Statistic graphs in primary education textbooks: A comparative study between Spain and Chile. Bolema Boletim Educ. Mat. 2016, 30, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, A.; González, J.; González, J. Reading and interpretation of statistical graphs, how does the citizen do it? Paradigma 2021, 42, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal Decree 157/2022; Organisation and Minimum Contents of Primary Education. State Official Newsletter: Madrid, Spain, 2022. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-3296 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Armas-Quintá, F.X.; Rodríguez-Lestegás, F.; Macía-Arce, X.C.; Pérez-Guilarte, Y. Teaching and learning landscape in primary education in Spain: A necessary curricular review to educate citizens. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2022, 62, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugdayci, I.; Selvi, H.Z. Do Maps Contribute to Pupils’ Learning Skills in Primary Schools? Cartogr. J. 2021, 58, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelková, L.; Hanus, M. Map skills in education: A systematic review of terminology, methodology, and influencing factors. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2019, 9, 361–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Græsli, J.A.; Lien, G. How can children best learn map skills? A step-by-step approach. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2024, 32, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cîineanu, M.-D.; Dulamă, M.E.; Hîrlav, C.; Pop, C. Developing analytical thinking through the use of maps in geography. Rom. Rev. Geogr. Educ. 2024, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Calurano-Tena, M.T.; Martín-Aguilar, C.; Esquivel-Martín, T.; Bravo-Torija, B. Preguntas en los libros de texto de Ciencias Naturales de Educación Primaria: ¿Procesando o reproduciendo contenidos? ReiDoCrea 2019, 8, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, S.N. The challenge of reading comprehension in primary education. Panorama 2019, 13, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J.M.; Esquivel-Martín, T. New Insights for Teaching the One Health Approach: Transformative Environmental Education for Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Aleixandre, M.P.; Crujeiras, B. Epistemic Practices and Scientific Practices in Science Education. In Science Education, New Directions in Mathematics and Science Education; Taber, K.S., Akpan, B., Eds.; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J. Teaching scientific practices: Meeting the challenge of change. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2014, 25, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimore, R.A. Preschool Science Education: A vision for the future. Early Child. Educ. J. 2020, 48, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiili, C.; Coiro, J.; Hämäläinen, J. An online inquiry tool to support the exploration of controversial issues on the Internet. J. Literacy Techno. 2016, 17, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S.C.H.; Wan, C.L.J.; Ko, S. Interactivity, active collaborative learning, and learning performance: The moderating role of perceived fun by using personal response systems. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2019, 17, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Khaskheli, A.; Qureshi, J.A.; Raza, S.A.; Yousufi, S.Q. Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 31, 2371–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R. The Effect of Collaborative Learning on Enhancing Student Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Doctoral Dissertation, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Strebe, D.D. An efficient technique for creating a continuum of equal-area map projections. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 45, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).