Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Background and Methodology

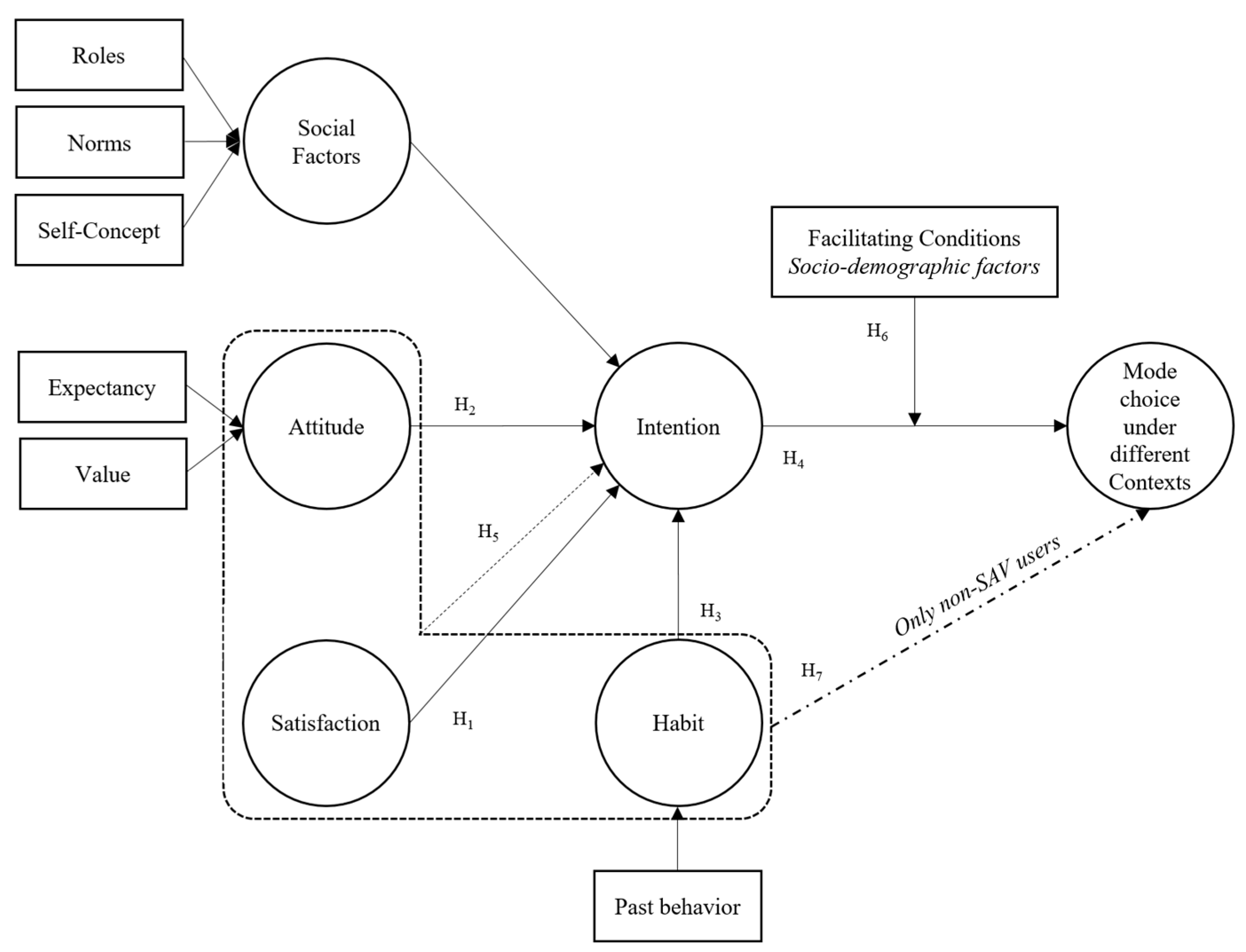

3.1. Theoretical Model and Research Hypotheses

3.2. Shanghai: City Context for the Study

3.3. Participants and Procedure

- Commuting patterns: primary mode, duration, and weekly frequency (see Table 3 for detailed commuting patterns).

- Attitudes: evaluated using a modified version of Steg’s [70] framework, associating 14 attributes with six travel modes.

- Travel satisfaction: measured using the Satisfaction with Travel Scale (STS) [71].

- Travel habits: assessed using an adapted seven-item version of the Self-Report Habit Index (SRHI) [27].

- Responses to contextual changes: examined through nine disruptive scenarios (see Table 3 for details).

- Demographics: age, gender, household characteristics, education, occupation, income, and driving-related information.

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Structural Equation Modeling for Transport Mode Choice

- Factor model: All items loading on a single factor.

- Factor model: SAT, ATD, and HAB items loading on one factor and INT and MOD as separate factors.

- Hypothesized five-factor model: SAT, ATD, HAB, INT, and MOD as distinct factors

4.2. Impact of Sociodemographics on SAV Choice: ANOVA

- Driver’s license: significantly affects choices during adverse weather (MOD1) and safety concerns (MOD6).

- Vehicle ownership: multi-car households adapt better to adverse weather disruptions (MOD1).

- Commute time: longer commutes correlate with SAV consideration in congestion (MOD2).

- Driving experience: experienced drivers navigate congestion independently (MOD2).

- Gender: influences safety perceptions (MOD6) and budget-driven choices (MOD8).

- Household size/income: impacts mode choice under financial constraints (MOD8).

4.3. Impact of Changes on Psychological Factors of Non-Users Adopting SAV: Logistic Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Summary of Literature on Naturally Occurring Contextual Changes

| Contextual Change | Studies | Transport Mode | Commuting Habit | ||

| Conventional | (S)AV | Frequency | Context | ||

| Adverse Weather Conditions | [14,15] | X | X | ||

| Extended Commute Duration Due to Congestion | [76] | X | X | ||

| Rushed Departure Due to Running Late | [36] | X | X | ||

| High Parking Costs and Scarcity | [42] | X | X | ||

| Pressure for On–Time Arrival | [77] | X | X | ||

| Safety Concerns | [71] | X | X | ||

| Change in Worksite Location | [77] | X | X | ||

| Budget Constraints | [36] | X | X | ||

| Obstructions on Usual Route Due to Construction/Events | [16,76] | X | X | ||

Appendix B. Factor Loadings and Reliability in Confirmatory Factor Analysis

| Latent Factors | Indicators | Factor | Communality | Unique | Cronbach’s Alpha | AVE | CR |

| Loading | Variance | ||||||

| Satisfaction | SAT1 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.91 | 0.54 | 0.9 |

| SAT2 | 0.85 | 0.72 | 0.28 | ||||

| SAT3 | 0.78 | 0.61 | 0.39 | ||||

| SAT4 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.47 | ||||

| SAT5 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | ||||

| SAT6 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.48 | ||||

| SAT7 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.71 | ||||

| SAT8 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.58 | ||||

| SAT9 | 0.61 | 0.37 | 0.62 | ||||

| Attitude | ATD1 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.82 | 0.57 | 0.9 |

| ATD2 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 | ||||

| ATD3 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.41 | ||||

| ATD4 | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.47 | ||||

| ATD5 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.45 | ||||

| ATD6 | 0.81 | 0.66 | 0.34 | ||||

| ATD7 | 0.8 | 0.64 | 0.36 | ||||

| Habit | HAB1 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.88 | 0.53 | 0.9 |

| HAB2 | 0.7 | 0.49 | 0.51 | ||||

| HAB5 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.54 | ||||

| HAB6 | 0.8 | 0.64 | 0.36 | ||||

| HAB7 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.58 | ||||

| HAB9 | 0.8 | 0.64 | 0.36 | ||||

| HAB10 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.44 | ||||

| Intention | INT1 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.81 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| INT2 | 0.7 | 0.49 | 0.51 | ||||

| INT3 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.54 | ||||

| INT4 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.59 | ||||

| INT5 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.48 | ||||

| INT6 | 0.6 | 0.36 | 0.64 | ||||

| INT7 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.52 | ||||

| INT8 | 0.58 | 0.34 | 0.66 | ||||

| INT9 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.54 |

Appendix C. Comparative Fit Indices Across Different Measurement Models

| Fit Index/Parameter | Permissible Range | 1–Factor Model | 3–Factor Model | 5–Factor Model |

| Chi–square (χ2) | As low as possible | 3400.19 | 2846.47 | 974.57 |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | As high as possible | 454 | 453 | 450 |

| Normed chi–square | Between 2 and 5 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 2.2 |

| p–value | <0.05 or 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | >0.90 or 0.95 | 0.565 | 0.646 | 0.923 |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | >0.90 or 0.95 | 0.524 | 0.613 | 0.915 |

| RMSEA | <0.08 | 0.112 | 0.101 | 0.047 |

| 90% CI for RMSEA | N.A. | [0.109, 0.116] | [0.098, 0.105] | [0.043, 0.052] |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | <0.08 | 0.139 | 0.127 | 0.06 |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Lowest model is the best | 61,277.39 | 60,725.67 | 58,859.77 |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | Lowest model is the best | 61,591.74 | 61,044.27 | 59,191.12 |

Appendix D. ANOVA Results for Hypothesis 6: Analysis of Sociodemographic Factors Influencing Mode Choice

| Variable | MOD1 | MOD2 | MOD3 | MOD4 | MOD5 | MOD 6 | MOD 7 | MOD 8 | MOD9 |

| Transport Mode | 0.079 | 0.489 | 0.537 | 0.023 * | 0.509 | 0.493 | 0.986 | 0.666 | 0.278 |

| Commute time | 0.3 | 0.032 * | 0.36 | 0.304 | 0.052 | 0.837 | 0.505 | 0.14 | 0.194 |

| Intention | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | 0.004 ** | <0.001 *** | 0.038 * | <0.001 *** |

| Gender | 0.406 | 0.841 | 0.946 | 0.989 | 0.584 | 0.018 * | 0.558 | 0.007 ** | 0.368 |

| Marital status | 0.586 | 0.202 | 0.681 | 0.462 | 0.59 | 0.275 | 0.323 | 0.406 | 0.354 |

| HH–size | 0.861 | 0.985 | 0.317 | 0.281 | 0.325 | 0.872 | 0.967 | 0.027 * | 0.904 |

| Education | 0.584 | 0.306 | 0.655 | 0.873 | 0.413 | 0.711 | 0.989 | 0.84 | 0.76 |

| Occupation | 0.393 | 0.639 | 0.38 | 0.595 | 0.396 | 0.807 | 0.235 | 0.462 | 0.36 |

| Income | 0.605 | 0.136 | 0.324 | 0.526 | 0.228 | 0.228 | 0.408 | 0.035 * | 0.44 |

| Driver’s License | 0.009** | 0.019* | 0.128 | 0.696 | 0.106 | 0.031 * | 0.173 | 0.425 | 0.954 |

| DL–Time | 0.179 | 0.02* | 0.002** | 0.588 | 0.098 | 0.593 | 0.441 | 0.917 | 0.66 |

| HH–Cars | 0.002** | 0.351 | 0.584 | 0.303 | 0.169 | 0.918 | 0.707 | 0.854 | 0.261 |

| Notes: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. | |||||||||

Appendix E. Logistic Regression Models Examining the Impact of Psychological Factors on SAV Mode Choice in Different Contexts

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 1 (Adverse Weather Conditions) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-Value | p-Value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.006 | 2.075 | −2.438 | 0.015 * | 1.01 | 1–1.43 |

| SAT | 1.124 | 0.057 | 2.036 | 0.042 * | 3.08 | 2.73–3.53 |

| ATD | 1.247 | 0.07 | 3.138 | 0.002 * | 3.48 | 2.97–4.2 |

| HAB | 1.108 | 0.073 | 1.404 | 0.16 | 3.03 | 2.62–3.6 |

| χ2 = 47.94, df = 16, p < 0.001 ***, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.133 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 2 (Extended Commute Duration due to Congestion) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.003 | 1.986 | −2.968 | 0.003 * | 1 | 1–1.14 |

| SAT | 0.986 | 0.051 | −0.29 | 0.772 | 2.68 | 2.44–2.97 |

| ATD | 1.237 | 0.068 | 3.149 | 0.002 * | 3.45 | 2.96–4.12 |

| HAB | 1.151 | 0.067 | 2.117 | 0.034 * | 3.16 | 2.75–3.73 |

| χ2 = 42.65, df = 16, p < 0.001 ***, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.111 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 3 (Rushed Departure due to Running Late) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.045 | 2.13 | −1.46 | 0.144 | 1.05 | 1–17.24 |

| SAT | 1.05 | 0.057 | 0.86 | 0.39 | 2.86 | 2.56–3.24 |

| ATD | 1.138 | 0.071 | 1.817 | 0.069 | 3.12 | 2.69–3.7 |

| HAB | 1.116 | 0.074 | 1.479 | 0.139 | 3.05 | 2.63–3.65 |

| χ2 = 35.01, df = 16, p = 0.004 *, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.101 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05. | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 4 (High Parking Costs and Scarcity) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.009 | 1.958 | −2.385 | 0.017 * | 1.01 | 1–1.52 |

| SAT | 1.026 | 0.053 | 0.481 | 0.631 | 2.79 | 2.52–3.13 |

| ATD | 1.164 | 0.068 | 2.233 | 0.026 * | 3.2 | 2.77–3.79 |

| HAB | 1.104 | 0.069 | 1.434 | 0.152 | 3.02 | 2.63–3.55 |

| χ2 = 35.4, df = 16, p = 0.004 *, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.096 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05. | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 5 (Pressure for Punctual Arrival) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.039 | 2.012 | −1.609 | 0.108 | 1.04 | 1–7.37 |

| SAT | 1.058 | 0.055 | 1.024 | 0.306 | 2.88 | 2.59–3.25 |

| ATD | 1.056 | 0.07 | 0.782 | 0.434 | 2.87 | 2.51–3.35 |

| HAB | 1.13 | 0.072 | 1.693 | 0.09 | 3.09 | 2.67–3.69 |

| χ2 = 23.3, df = 16, p = 0.106, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.066 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 6 (Safety Concerns) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.006 | 2.392 | −2.126 | 0.033 * | 1.01 | 1–1.93 |

| SAT | 1.088 | 0.068 | 1.243 | 0.214 | 2.97 | 2.6–3.47 |

| ATD | 1.042 | 0.082 | 0.503 | 0.615 | 2.83 | 2.42–3.38 |

| HAB | 1.116 | 0.085 | 1.281 | 0.2 | 3.05 | 2.58–3.76 |

| χ2 = 19.7, df = 16, p = 0.234, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.064 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05 | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 7 (Change in Worksite Location) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.001 | 2.195 | −3.168 | 0.002 * | 1 | 1–1.07 |

| SAT | 1.058 | 0.058 | 0.968 | 0.333 | 2.88 | 2.57–3.28 |

| ATD | 1.127 | 0.071 | 1.688 | 0.091 | 3.09 | 2.67–3.65 |

| HAB | 1.289 | 0.08 | 3.153 | 0.002 * | 3.63 | 3.02–4.56 |

| χ2 = 36.69, df = 16, p = 0.002 *, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.105 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05 | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 8 (Budget Constraints) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.016 | 3.121 | −1.334 | 0.182 | 1.02 | 1–1381 |

| SAT | 0.963 | 0.085 | −0.445 | 0.657 | 2.62 | 2.26–3.13 |

| ATD | 1.141 | 0.096 | 1.379 | 0.168 | 3.13 | 2.56–3.95 |

| HAB | 1.16 | 0.117 | 1.277 | 0.202 | 3.19 | 2.54–4.37 |

| χ2 = 27.18, df = 16, p = 0.04 *, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.115 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05 | ||||||

| SAV Mode Choice in Context 9 (Obstructions on Usual Route due to Construction/Events) | ||||||

| Variable | B | SE | z-value | p-value | OR | 95% CI |

| (Intercept) | 0.005 | 2.459 | −2.143 | 0.032 * | 1.01 | 1–1.86 |

| SAT | 1.109 | 0.067 | 1.541 | 0.123 | 3.03 | 2.65–3.55 |

| ATD | 1.018 | 0.079 | 0.231 | 0.818 | 2.77 | 2.39–3.27 |

| HAB | 1.318 | 0.094 | 2.938 | 0.003 * | 3.74 | 3.01–4.93 |

| χ2 = 41.58, df = 16, p <0.001 ***, Nagelkerke R2 = 0.131 | ||||||

| Notes: B = coefficient, SE = standard error, OR = odds ratio, 95% CI = 95% confidence interval, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 | ||||||

References

- Gao, Y.; Newman, P.; Kenworthy, J. The Rise and Decline of Car Use in Beijing and Shanghai. In Sustainability in Urban Planning and Design; Almusaed, A., Almssad, A., Truong-Hong, L., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020; ISBN 978-1-83880-351-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, X.; Du, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J. Identifying the factors influencing the choice of different ride-hailing services in Shenzhen, China. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. China Mobile Source Environmental Management Annual Report 2023; Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023; p. 60. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/ydyhjgl/202312/W020231211531753967096.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- Kenworthy, J. Is Automobile Dependence in Emerging Cities an Irresistible Force? Perspectives from São Paulo, Taipei, Prague, Mumbai, Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldakkhelallah, A.; Alamri, A.S.; Georgiou, S.; Simic, M. Public Perception of the Introduction of Autonomous Vehicles. WEVJ 2023, 14, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givoni, M. Re-assessing the Results of the London Congestion Charging Scheme. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, D. Tackling urban traffic congestion: The experience of London, Stockholm and Singapore. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2018, 6, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Zhang, K.; Nie, Y.; Xu, J. Dynamic carpool in morning commute: Role of high-occupancy-vehicle (HOV) and high-occupancy-toll (HOT) lanes. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2020, 135, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B. Modelling motivation and habit in stable travel mode contexts. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarabi, Z.; Manaugh, K.; Lord, S. The impacts of residential relocation on commute habits: A qualitative perspective on households’ mobility behaviors and strategies. Travel Behav. Soc. 2019, 16, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Scheiner, J. Understanding Changing Travel Behaviour over the Life Course: Contributions from Biographical Research. 2015. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Understanding-changing-travel-behaviour-over-the-Chatterjee-Scheiner/1b36c37aa43136167e81bc6100ced432ebf604fa (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Jones, C.H.; Ogilvie, D. Motivations for active commuting: A qualitative investigation of the period of home or work relocation. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiner, J.; Holz-Rau, C. A comprehensive study of life course, cohort, and period effects on changes in travel mode use. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2013, 47, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloc, I.; Gimenez-Nadal, J.I.; Molina, J.A. Weather Conditions and Daily Commuting. IZA Discussion Papers, Art. no. 15661, Oct. 2022. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org//p/iza/izadps/dp15661.html (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Liu, C.; Susilo, Y.O.; Karlström, A. Investigating the impacts of weather variability on individual’s daily activity–travel patterns: A comparison between commuters and non-commuters in Sweden. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 82, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Gärling, T.; Kitamura, R. Changes in Drivers’ Perceptions and Use of Public Transport during a Freeway Closure: Effects of Temporary Structural Change on Cooperation in a Real-Life Social Dilemma. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnant, D.J.; Kockelman, K.M. Dynamic ride-sharing and fleet sizing for a system of shared autonomous vehicles in Austin, Texas. Transportation 2018, 45, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Rashidi, T.H.; Rose, J.M. Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 69, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, M.; Stathopoulos, A.; Shiftan, Y.; Walker, J.L. What do we (Not) know about our future with automated vehicles? Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 123, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.D.; Correia, G.; van Arem, B. Preferences of travellers for using automated vehicles as last mile public transport of multimodal train trips. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2016, 94, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Wood, W. Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits. J. Public Policy Mark. 2006, 25, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Walker, I.; Davis, A.; Jurasek, M. Context change and travel mode choice: Combining the habit discontinuity and self-activation hypotheses. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Interpersonal Behavior; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co: Monterey, CA, USA, 1977; ISBN 978-0-8185-0188-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lally, P.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.M.; Potts, H.W.W.; Wardle, J. How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 40, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Choice of Travel Mode in the Theory of Planned Behavior: The Roles of Past Behavior, Habit, and Reasoned Action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H.; Van Knippenberg, A.; Van Knippenberg, C. Attitude Versus General Habit: Antecedents of Travel Mode Choice. J. Appl. Soc. Pyschol. 1994, 24, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Orbell, S. Reflections on Past Behavior: A Self-Report Index of Habit Strength 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, W.; Rünger, D. Psychology of Habit. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B. A review and analysis of the use of ‘habit’ in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Akiva, M.E. Discrete Choice Analysis: Theory and Application to Travel Demand, 1st ed.; Mit Pr: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-262-02217-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, C.R.; Koppelman, F.S. Activity-Based Modeling of Travel Demand. In Handbook of Transportation Science; Hall, R.W., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 35–61. ISBN 978-1-4615-5203-1. [Google Scholar]

- Small, K. The Scheduling of Consumer Activities: Work Trips. Am. Econ. Rev. 1982, 72, 467–479. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, S.; Polak, J.W.; Daly, A.; Hyman, G. Flexible substitution patterns in models of mode and time of day choice: New evidence from the UK and the Netherlands. Transportation 2007, 34, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, C.R. Analysis of travel mode and departure time choice for urban shopping trips. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 1998, 32, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, I.; Thomas, G.O.; Verplanken, B. Old Habits Die Hard: Travel Habit Formation and Decay During an Office Relocation. Environ. Behav. 2015, 47, 1089–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgari, H.; Jin, X. Incorporating habitual behavior into Mode choice Modeling in light of emerging mobility services. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Cervero, R. Travel and the Built Environment: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2010, 76, 265–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The importance of timing for breaking commuters’ car driving habits. Habits Consum. 2012, 12, 130–140. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: Testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis in a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S. Is a Residential Relocation a Good Opportunity to Change People’s Travel Behavior? Results From a Theory-Driven Intervention Study. Environ. Behav. 2006, 38, 820–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.B.; Werner, C.M.; Kim, N. Personal and Contextual Factors Supporting the Switch to Transit Use: Evaluating a Natural Transit Intervention. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2003, 3, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, B.; Chatterjee, K.; Melia, S.; Knies, G.; Laurie, H. Life events and travel behavior: Exploring the interrelationship using UK household longitudinal study data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2413, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandsart, D. The impact of life events on travel behaviour. In Re-Thinking Mobility Poverty; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley series in social psychology; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-201-02089-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69748-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anable, J. ‘Complacent Car Addicts’ or ‘Aspiring Environmentalists’? Identifying travel behaviour segments using attitude theory. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Chao, W.-H. Habitual or reasoned? Using the theory of planned behavior, technology acceptance model, and habit to examine switching intentions toward public transit. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboucha, C.J.; Ishaq, R.; Shiftan, Y. User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 78, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, F.; Noruzoliaee, M.; Mohammadian, A. (Kouros) Shared versus private mobility: Modeling public interest in autonomous vehicles accounting for latent attitudes. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2018, 97, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddeu, D.; Parkhurst, G.; Shergold, I. Passenger comfort and trust on first-time use of a shared autonomous shuttle vehicle. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H.; Knippenberg, A.; Moonen, A. Habit versus planned behaviour: A field experiment. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 37, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, I.J.; Cooper, S.R.; Conchie, S.M. An extended theory of planned behaviour model of the psychological factors affecting commuters’ transport mode use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; Surrey, G. Motivating Sustainable Consumption; Sustainable Development Research Network: London, UK, 2005; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Martiskainen, M. Affecting Consumer Behaviour on Energy Demand; University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Donald, I.; Canter, D. Intentionality and fatality during the King’s Cross underground fire. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.; Huang, H.; Ran, B.; Zhan, F.; Shi, Y. Exploring the Factors Affecting Mode Choice Intention of Autonomous Vehicle Based on an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior—A Case Study in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, I.M.Y.; Pee, L.G. Behavioral Factors Affecting Internet Abuse in the Workplace—An Empirical Investigation. 2004. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Behavioral-Factors-Affecting-Internet-Abuse-in-the-Woon-Pee/0ff825dc69968c97fad79e018fa0737a639082f4 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Milhausen, R.R.; Reece, M.; Perera, B. A theory-based approach to understanding sexual behavior at Mardi Gras. J. Sex Res. 2006, 43, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pee, L.G.; Woon, I.M.Y.; Kankanhalli, A. Explaining non-work-related computing in the workplace: A comparison of alternative models. Inf. Manag. 2008, 45, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.-P.; Godin, G.; Gagné, C.; Fortin, J.-P.; Lamothe, L.; Reinharz, D.; Cloutier, A. An adaptation of the theory of interpersonal behaviour to the study of telemedicine adoption by physicians. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2003, 71, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, B.; Wandersman, A. Predicting Undergraduate Condom Use with the Fishbein and Ajzen and the Triandis Attitude-Behavior Models: Implications for Public Health Interventions. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 21, 1810–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domarchi, C.; Tudela, A.; González, A. Effect of attitudes, habit and affective appraisal on mode choice: An application to university workers. Transportation 2008, 35, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, R.J.; Treloar, C. Prediction of intern attendance at a seminar-based training programme: A behavioural intention model. Med. Educ. 2000, 34, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. Available online: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/tjnj2022e.htm (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Shanghai: The Average Daily Passenger Volume of Public Transportation Reached 13.99 Million Last Year, with Rail Transit Accounting for 70%. Available online: https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_20110819 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Shanghai Transportation Development Research Center. Shanghai MaaS Public Travel Annual Report (2023); Shanghai Transportation Development Research Center: Shanghai, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Axhausen, K.W.; Jin, Y. Assessing one-way carsharing’s impacts on vehicle ownership: Evidence from Shanghai with an international comparison. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 150, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. Car use: Lust and must. Instrumental, symbolic and affective motives for car use. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2005, 39, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D.; Gärling, T.; Eriksson, L.; Friman, M.; Olsson, L.E.; Fujii, S. Satisfaction with travel and subjective well-being: Development and test of a measurement tool. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E.J.; Harrington, K.M.; Clark, S.L.; Miller, M.W. Sample Size Requirements for Structural Equation Models: An Evaluation of Power, Bias, and Solution Propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. xvii, 534. ISBN 978-1-4625-2334-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L. Subways, Strikes, and Slowdowns: The Impacts of Public Transit on Traffic Congestion. Am. Econ. Rev. 2014, 104, 2763–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guell, C.; Panter, J.; Jones, N.R.; Ogilvie, D. Towards a differentiated understanding of active travel behaviour: Using social theory to explore everyday commuting. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Contextual Change |

|---|---|

| MOD1 | Adverse Weather Conditions |

| MOD2 | Extended Commute Duration Due to Congestion |

| MOD3 | Rushed Departure Due to Running Late |

| MOD4 | High Parking Costs and Scarcity |

| MOD5 | Pressure for On–Time Arrival |

| MOD6 | Safety Concerns |

| MOD7 | Change in Worksite Location |

| MOD8 | Budget Constraints |

| MOD9 | Obstructions on Usual Route Due to Construction/Events |

| Demographics | Characteristics | n | % Within Group | % of Population | Demographics | Characteristics | n | % Within Group | % of Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–29 | 126 | 24.3 | Occupation | Blue–collar worker | 35 | 6.8 | |||

| 30–39 | 292 | 56.5 | White–collar worker | 408 | 78.9 | |||||

| 40–49 | 79 | 15.3 | Governmental job | 29 | 5.6 | |||||

| 50+ | 20 | 3.9 | Student | 30 | 5.8 | |||||

| Gender | Female | 249 | 48.2 | 48.2 | Others | 15 | 2.9 | Average annual income of employees: 96,011 ¥ | ||

| Male | 268 | 51.8 | 51.8 | Annual Income | ¥10,000–¥49,999 | 147 | 28.5 | |||

| Marital Status | Divorced/widowed | 4 | 0.8 | 7.6 | ¥50,000–¥99,999 | 112 | 21.6 | |||

| Married | 394 | 76.2 | 72.2 | ¥100,000–¥149,999 | 137 | 26.5 | ||||

| Never Married | 119 | 23 | 20.2 | ¥150,000 or more | 121 | 23.4 | ||||

| Household size | 1 Person | 12 | 2.3 | Average persons per household: 2.63 persons | Car driver’s license | Yes | 459 | 88.8 | ||

| 2 Persons | 28 | 5.4 | No | 58 | 11.2 | |||||

| 3 Persons | 277 | 53.6 | Time with driver’s license | 0–2 years | 50 | 10.9 | ||||

| 4 Persons | 115 | 22.2 | 2–5 years | 115 | 25.1 | |||||

| 5+ Persons | 85 | 16.5 | 5–10 years | 187 | 40.7 | |||||

| Education | High school or lower | 20 | 3.9 | 10+ years | 107 | 23.3 | ||||

| Bachelors | 438 | 84.7 | 61.0 | Car ownership within household | 0 cars | 51 | 9.9 | |||

| Masters or higher | 59 | 11.4 | 1 car | 349 | 67.5 | |||||

| 2 cars | 112 | 21.7 | ||||||||

| 3 or more cars | 5 | 0.9 |

| Item | Options | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Commute Mode | Car | 204 | 39.5% |

| Public Transport | 257 | 49.7% | |

| Walking & Bicycle | 56 | 10.8% | |

| Frequency of Commute (Times per Week) | <5 | 68 | 13.2% |

| 5 | 449 | 86.8% | |

| Commute Duration | 10 min or less | 7 | 1.4% |

| 10–20 min | 75 | 14.5% | |

| 20–30 min | 127 | 24.6% | |

| 30–45 min | 168 | 32.5% | |

| 45–60 min | 95 | 18.4% | |

| 60+ min | 45 | 8.7% |

| Path | Standardized Estimate | Standard Error | t–Value | R2 | Hypothesis Accepted/Rejected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Satisfaction (SAT) → Intention (INT) | 0.622 | 0.197 | 3.912 *** | 0.39 | Accepted |

| H2: Attitude (ATD) → Intention (INT) | 0.36 | 0.084 | 4.487 *** | 0.13 | Accepted |

| H3: Habit (HAB) → Intention (INT) | 0.449 | 0.107 | 4.552 *** | 0.2 | Accepted |

| H4: Satisfaction (SAT), Attitude (ATD), Habit (HAB) → Intention (INT) | 0.72 | Accepted | |||

| H5: Intention (INT) → Mode Choice (MOD) | 0.238 | 0.081 | 3.030 *** | 0.06 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

La Delfa, A.; Han, Z. Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041614

La Delfa A, Han Z. Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles? Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041614

Chicago/Turabian StyleLa Delfa, Alessandro, and Zheng Han. 2025. "Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles?" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041614

APA StyleLa Delfa, A., & Han, Z. (2025). Breaking Commuting Habits: Are Unexpected Urban Disruptions an Opportunity for Shared Autonomous Vehicles? Sustainability, 17(4), 1614. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041614