Land Consolidation and Its Effects on Afforested Agricultural Land: A Case Study of Ukraine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

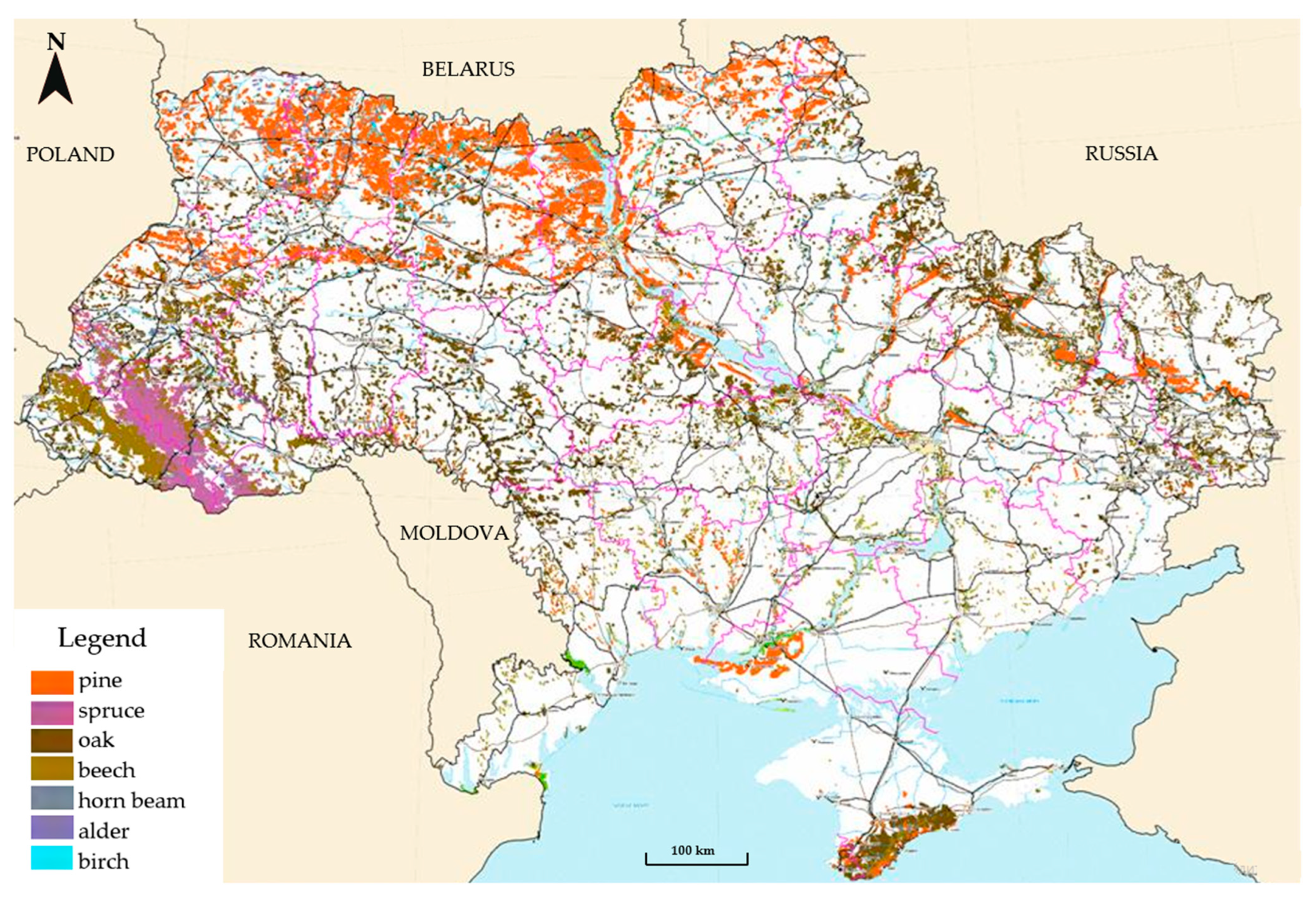

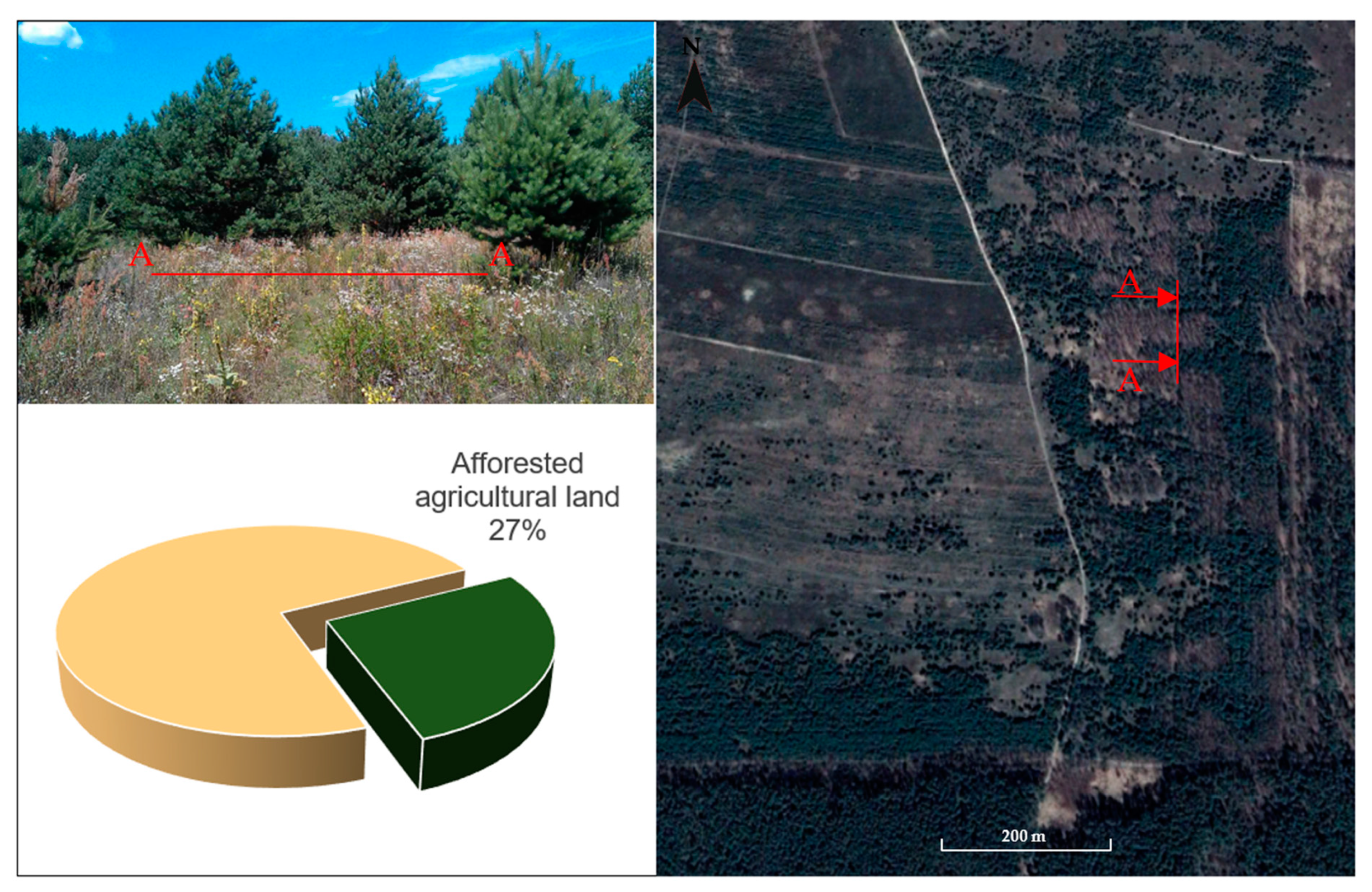

2.1. Natural Afforestation

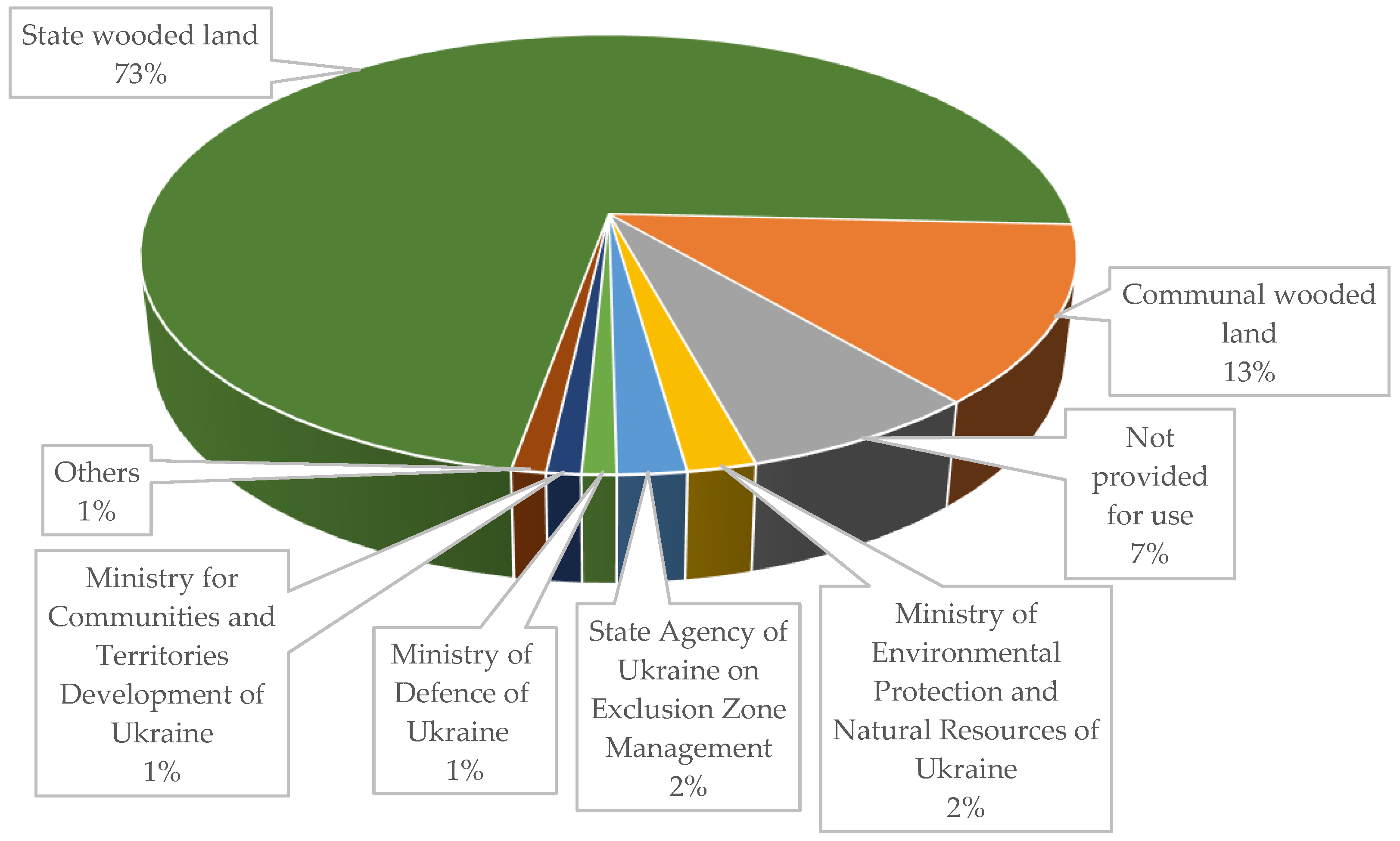

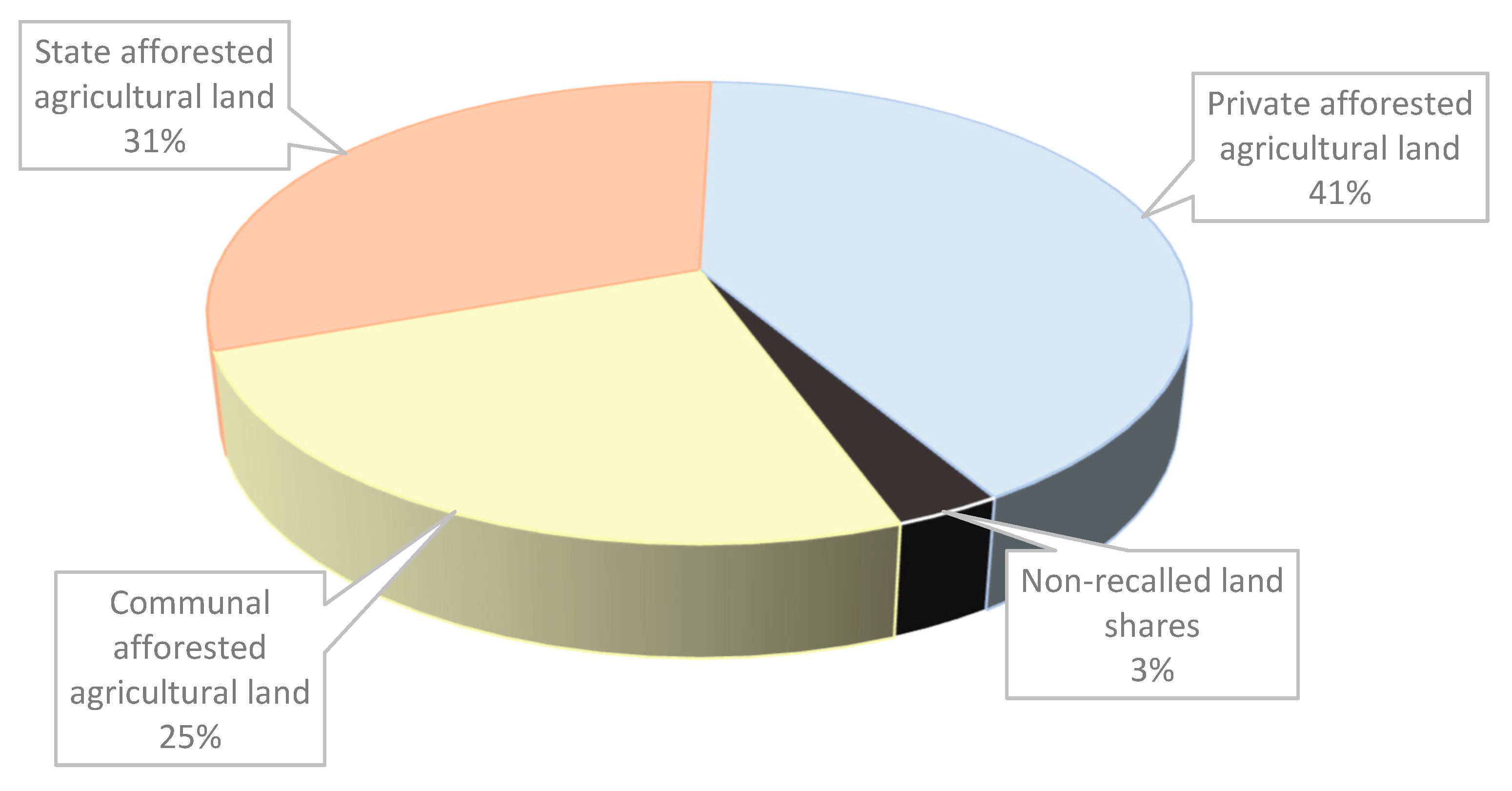

2.2. Land Reserves

2.3. Study Area

3. Results

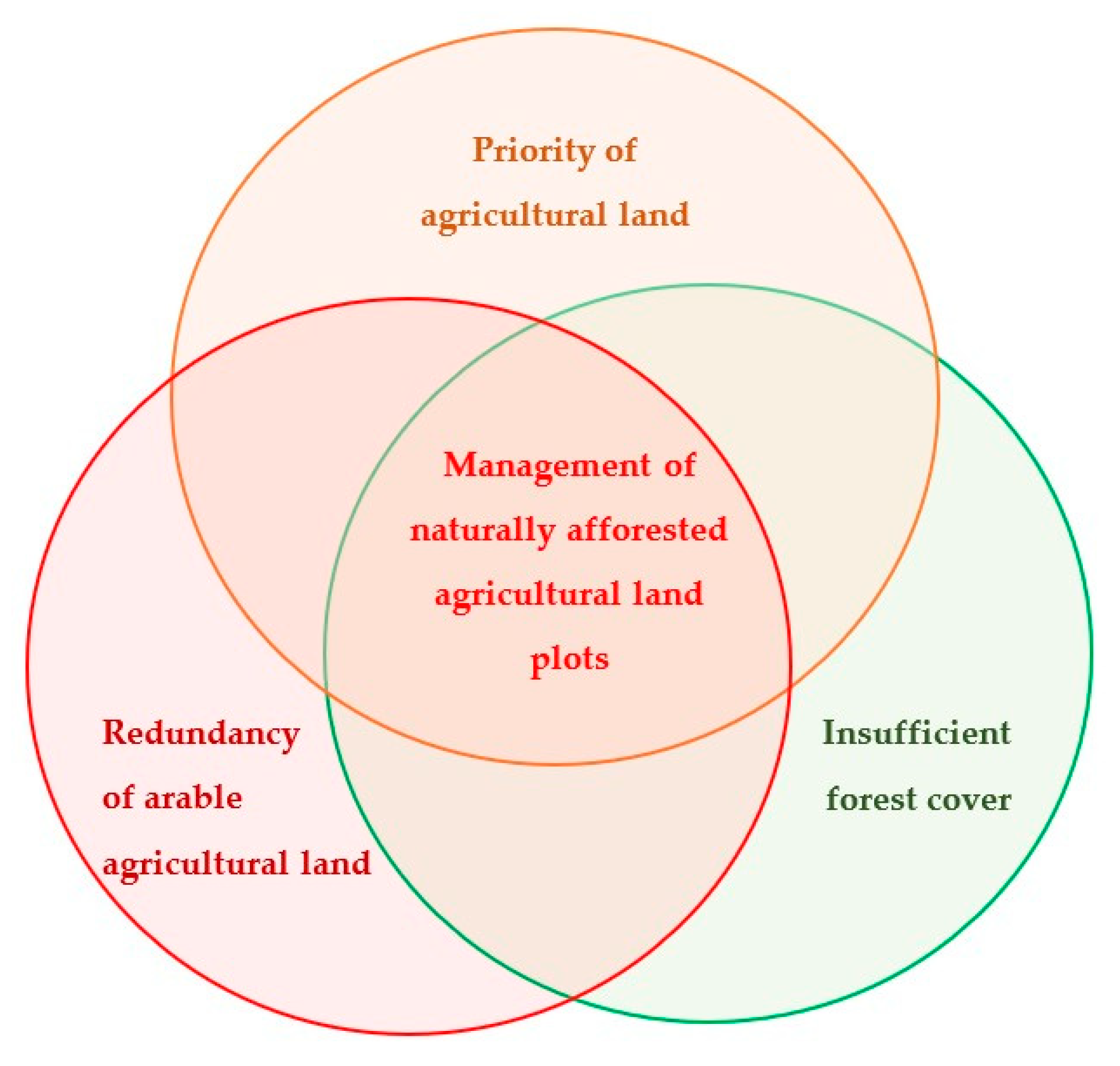

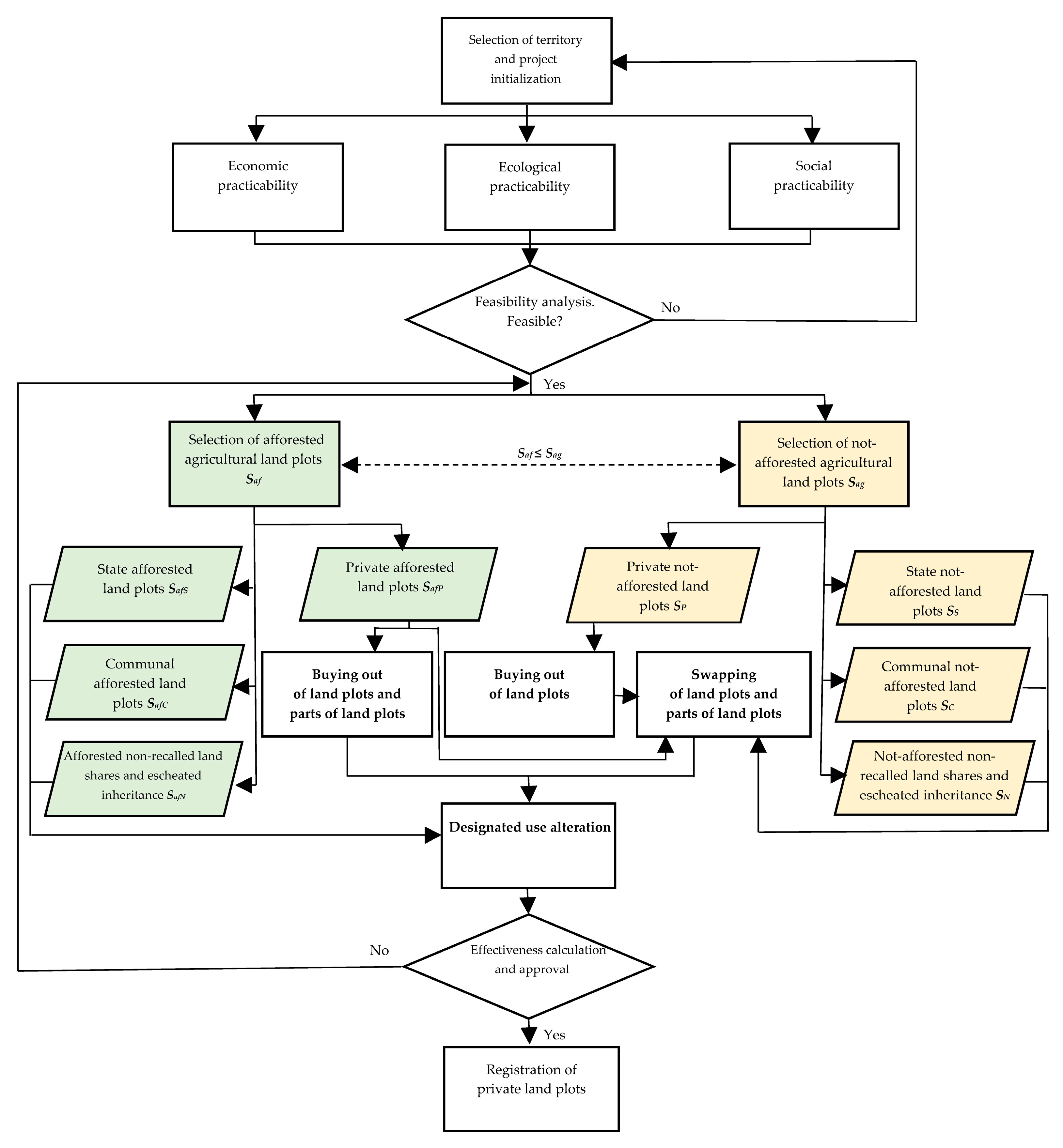

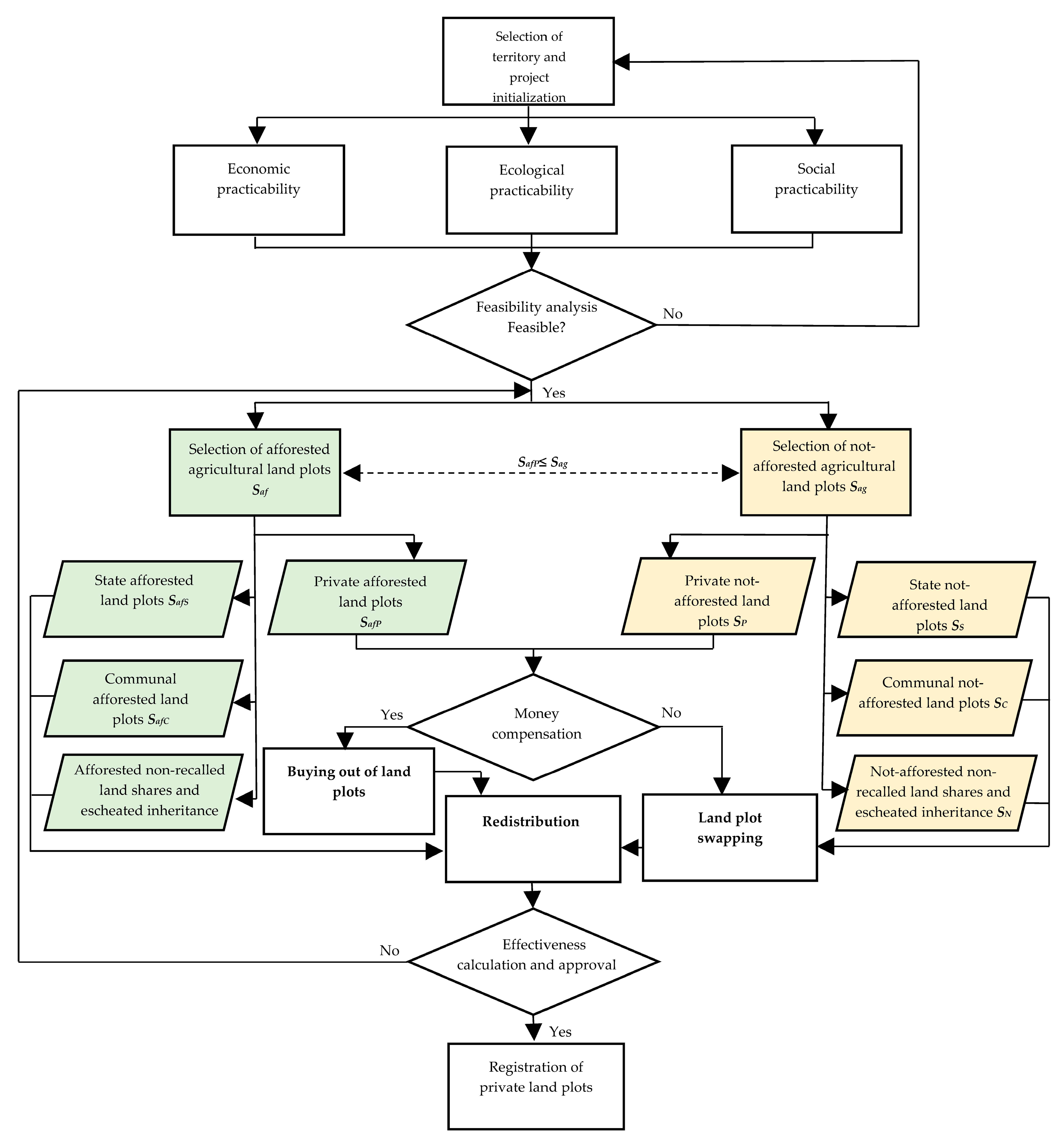

3.1. Land Consolidation Aiming at the Issue of Natural Agricultural Land Afforestation

- By buying out and swapping the land plots with keeping the initial land plot boundaries as much as possible (algorithm 1);

- Land consolidation by land plot reallotment with the alteration of boundaries of the initial land plots (algorithm 2).

- Buying out the afforested private land plots at the landowners’ will;

- Buying out the afforested parts of private land plots at the landowners’ will;

- Buying out the not-afforested private land plots at the landowners’ will;

- Involvement of not-afforested state and communal agricultural land plots, non-recalled land shares, and escheated inheritance;

- Involvement of afforested state and communal agricultural land plots, non-recalled land shares, and escheated inheritance;

- Swapping the afforested private land plots for not-afforested land plots;

- Swapping the afforested parts of private land plots for not-afforested parts of land plots;

- Alteration of the designated use of the afforested land plots, bought out and swapped from private landowners;

- Alteration of the designated use of the afforested state and communal land plots;

- Registration of land plots in the State Cadastre.

- Buying out the afforested private land plots at the landowners’ will;

- Buying out the not-afforested private land plots at the landowners’ will;

- Involvement of not-afforested state and communal agricultural land, non-recalled land shares, and escheated inheritance;

- Reallotment by swapping the afforested private land plots for not-afforested land plots;

- Land redistribution: compact agricultural land plots and forest land plots are developed;

- Registration of land plots in the State Cadastre.

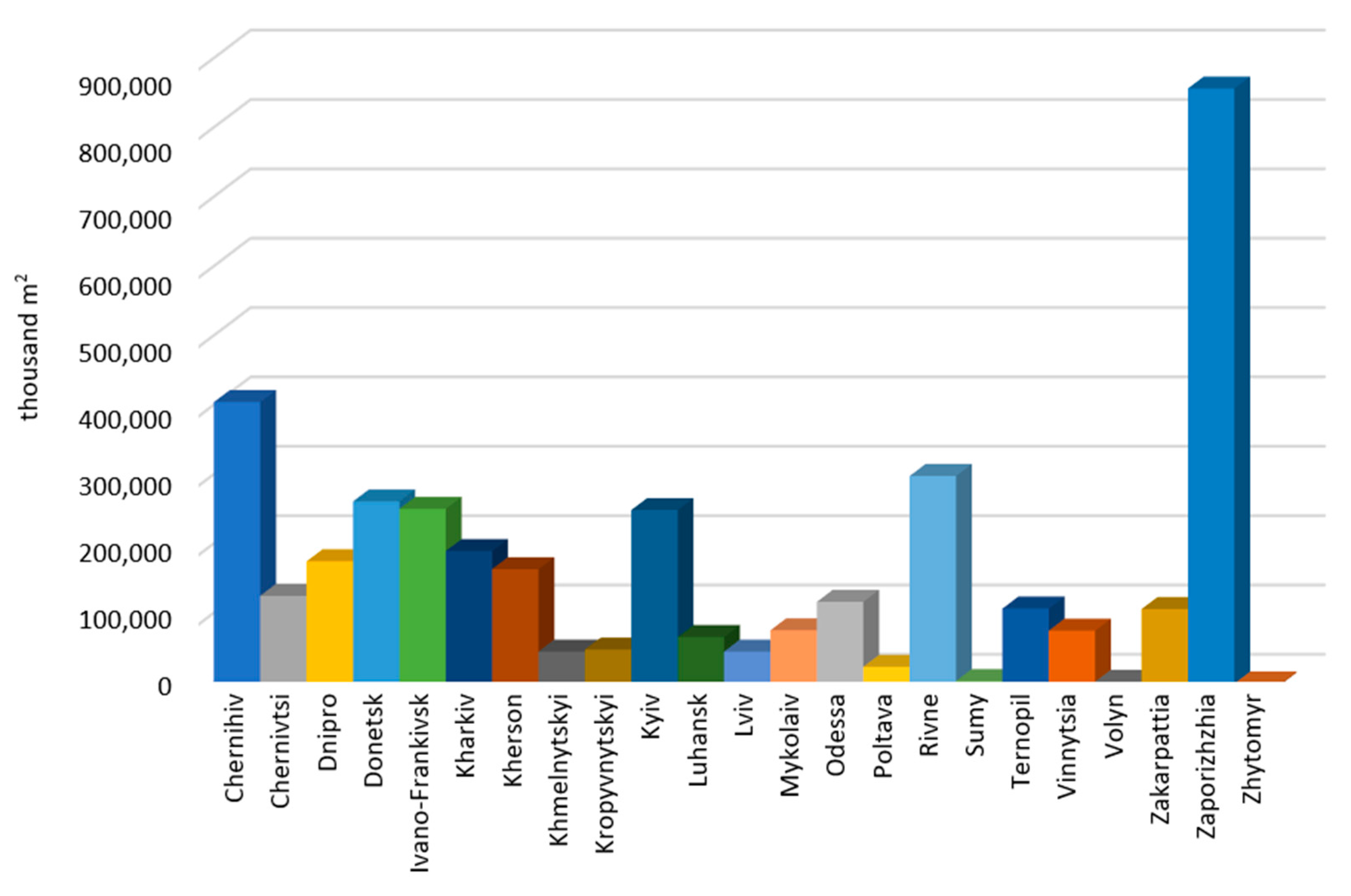

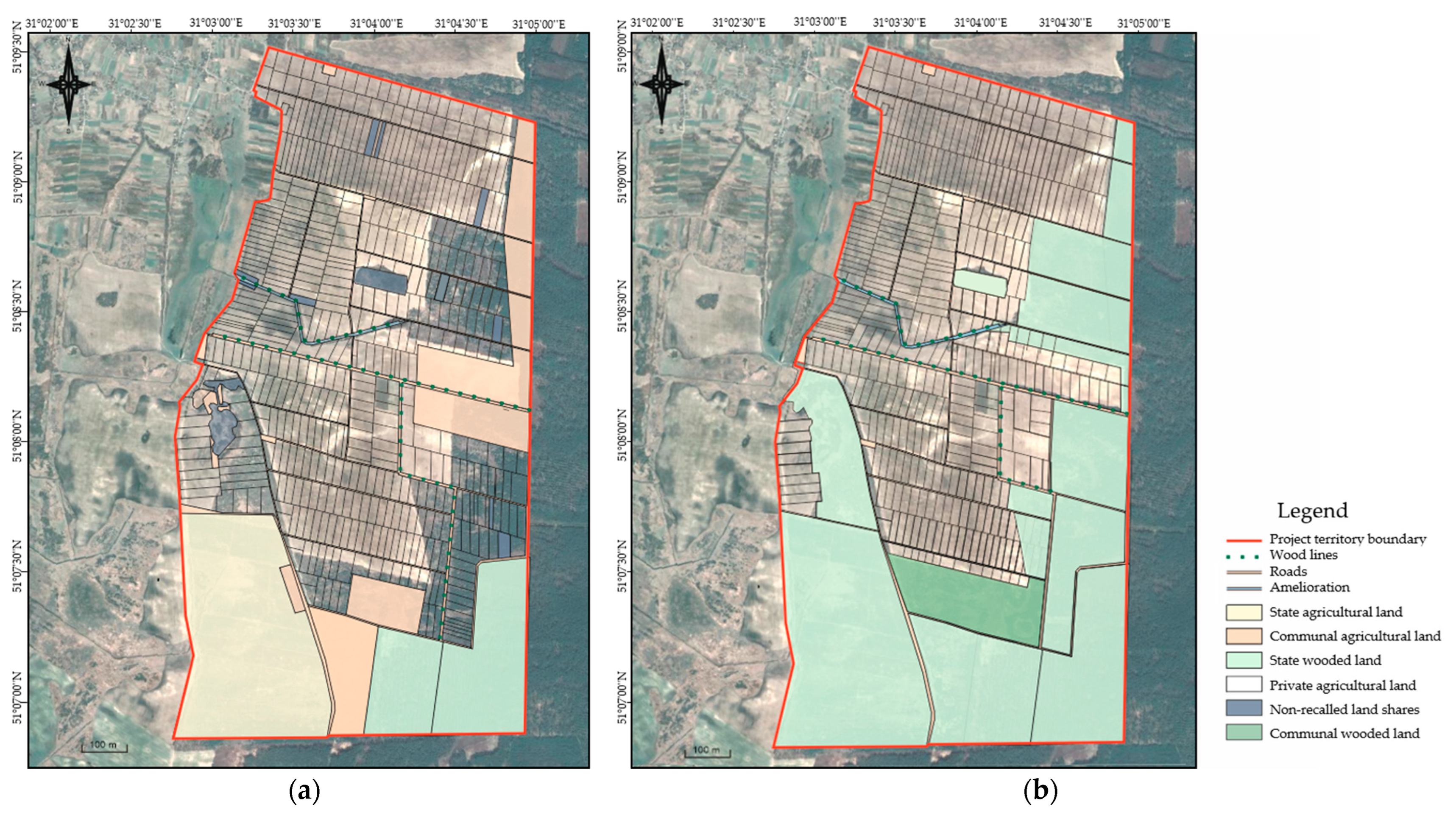

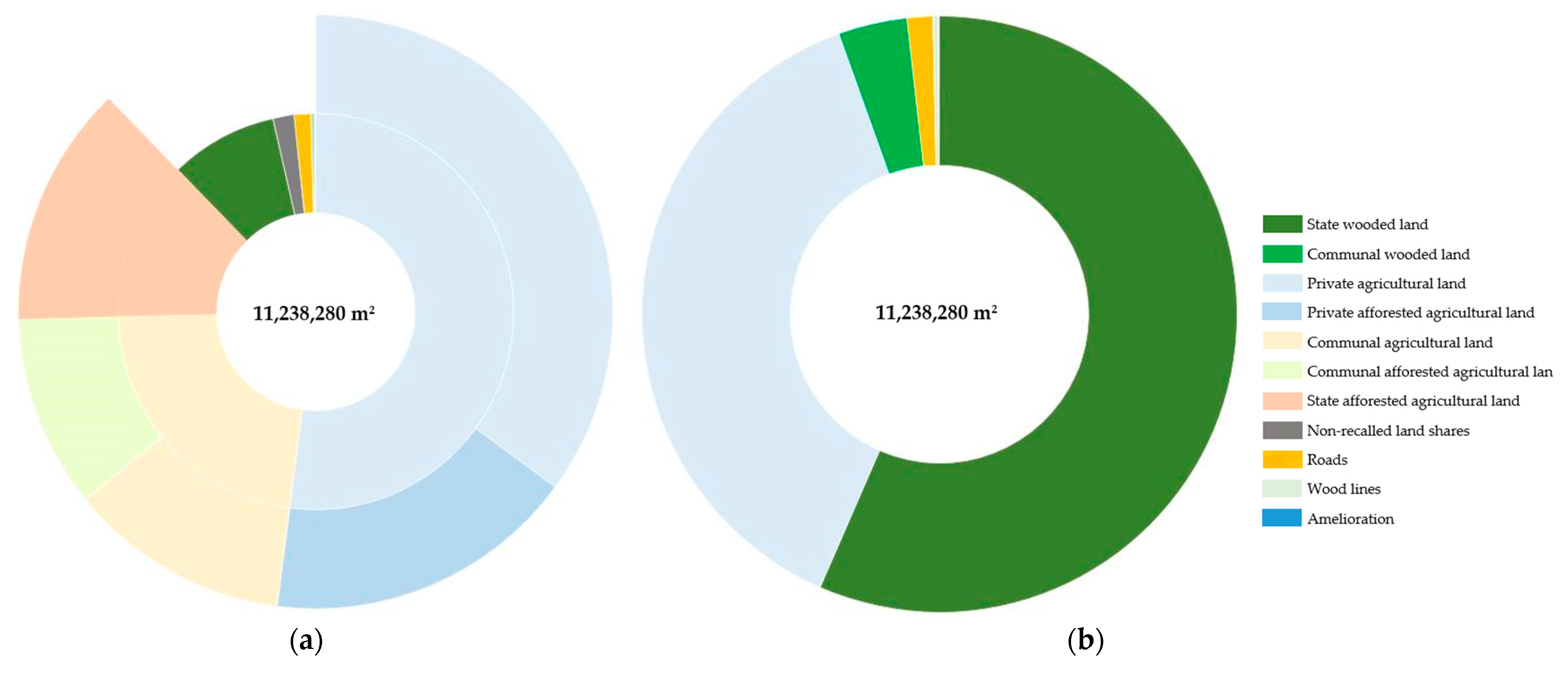

3.2. Practical Approbation of the Methodology

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The protracted period of natural afforestation;

- The prospects of keeping the natural forest cover for the purpose of increasing the forest cover area and nature conservation;

- Prevention of forest land fragmentation;

- Provision of agricultural land to local communities for agriculture to improve food security.

- The issue of naturally afforested agricultural land;

- Optimization of configuration, area, and placement of agricultural land;

- Optimization of configuration, area, and placement of forest land;

- Road network optimization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kies, U.; Peter, A. Forest Land Consolidation of Community Forests in North Rhine-Westphalia. Readjustment of Property as a Solution for Land Fragmentation and Inactive Small-Scale Private Forest Owners in Germany. EFI European Forest Institute, IIWH Internationales Institut für Wald und Holz e.V., BRA Bezirksregierung Arnsberg Dezernat 33. 2017. Available online: https://surl.li/pjaaig (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- Kolis, K. Jointly Owned Forests and Forest Land Consolidation—Increasing the Stand Size in Fragmented Areas. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2016, 11, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Demetriou, D. Land Consolidation. In The Development of an Integrated Planning and Decision Support System (IPDSS) for Land Consolidation; Springer Theses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 2–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural Amendment Act 2005. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC089280/ (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Hartvigsen, M. The potential of multi-purpose land consolidation in Eastern Europe. In Proceedings of the XXVII International FIG Congress, Warsaw, Poland, 11–15 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dacko, M.; Wojewodzic, T.; Pijanowski, J.; Janus, J.; Dacko, A.; Taszakowski, J. Increase in the market value of land as an effect of land consolidation projects. Acta Sci. Polonorum. Oecon. 2023, 22, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvestad, H.E.; Sky, P.K. Effects of land consolidation. Nord. J. Surv. Real Estate Res. 2019, 14, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolis, K.; Hiironen, J.; Riekkinen, K.; Vitikainen, A. Forest land consolidation and its effect on climate. Land Use Policy 2017, 61, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, Z.; Bílek, L.; Remeš, J.; Vacek, S.; Cukor, J.; Gallo, J.; Šimůnek, V.; Bulušek, D.; Brichta, J.; Vacek, O.; et al. Afforestation suitability and production potential of five tree species on abandoned farmland in response to climate change, Czech Republic. Trees 2022, 36, 1369–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gniadek, J.; Pijanowski, J.M.; Śmigielski, M. Impact of the forest succession on efficiency of the arable land production. J. Water Land Dev. 2017, 34, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukor, J.; Vacek, Z.; Linda, R.; Sharma, R.; Vacek, S. Afforested farmland vs. forestland: Effects of bark stripping by Cervus elaphus and climate on production potential and structure of Picea abies forests. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ustaoglu, E.; Collier, M.J. Farmland abandonment in Europe: An overview of drivers, consequences, and assessment of the sustainability implications. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, C.; Beilin, R.; Folke, C.; Lindborg, R. Farmland abandonment: Threat or opportunity for biodiversity conservation? A global review. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Directive “On the Approval of Government Strategy on Forest Management of Ukraine to 2035”, Dated 29 December 2021, No 1777-р. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1777-2021-%D1%80?lang=en#Text (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Suuriniemi, I.; Matero, J.; Hänninen, H.; Uusivuori, J. Factors Affecting Enlargement of Family Forest Holdings. Silva Fenn. 2012, 46, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdesmäki, M.; Matilainen, A.; Lehto, P. Forest owner or shareholder? Ownership feelings in a jointly-owned forest. Scand. J. For. Res. 2023, 38, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neykov, N.; Antov, P.; Dobrichov, I.; Halalisan, A.; Kitchoukov, E. The consolidation of forest territories as a tool to improve their management. PEB 2020, 1, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, C. Permissive Regulations and Forest Protection. Stud. Comp. Int. Dev. 2024, 59, 313–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. UNEP: The State of the World’s Forests 2020. Forests, Biodiversity and People. Rome. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/d0f20c1c-7760-4d94-86c3-d1e770a17db0 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- State Forest Resources Agency of Ukraine. Available online: https://forest.gov.ua/napryamki-diyalnosti/lisi-ukrayini/zagalna-harakteristika-lisiv-ukrayini (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Korchuvannya. Available online: https://korchuvannya.com.ua/korchuvannya/ (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/RL (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. The Land Code of Ukraine Dated 25 October 2001, No 2768-III. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2768-14/ed20220609#n319 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Forester Society of Ukraine. Available online: https://tlu.kiev.ua/nasha-dijalnist/profesiino-pro-lis/objektivna-informacija-shchodo-lisiv.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Veršinskas, T.; Vidar, M.; Hartvigsen, M.; Mitic Arsova, K.; Van Holst, F.; Gorgan, M. Legal Guide on Land Consolidation. FAO Legal Guide (FAO) Eng No. 3. 2020. Available online: https://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA9520EN/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Delo. Available online: https://delo.ua/agro/nevitrebuvani-payi-mozut-konfiskuvati-u-komunalnu-vlasnist-z-2025-roku-yak-fermeru-oformiti-dilyanku-428558/ (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Principal Directorate of the State Service of Ukraine for Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre in Kyiv and Kyiv Region. Available online: https://kyivska.land.gov.ua/pro-kolektyvnu-vlasnist/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine The Civil Code of Ukraine Dated 16 January 2003, No 435-IV. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/en/435-15?lang=en (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. The Law of Ukraine “On the Procedure of Allocation of Land Plots in Kind (in Places) to the Owners of Land Plots (Shares) (Portions (Pay))”, Dated 5 June 2003, No 899-IV. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/en/899-15#Text (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Chernihivoblagrolis Municipal Company. Available online: https://kp.chor-lis.com.ua/forests (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- North Interregional Directorate of Forest and Hunting Sector. Available online: https://n.forest.gov.ua/novini/zbilshimo-lisistist-chernigivshhini/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Kipti Village Amalgamated Territorial Community. Available online: https://hromada.canactions.com/kiptivska/ (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. The Resolution “ About the Approval of the Order of the State Land Cadastre”, Dated 17 October 2012, No 1051. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/en/1051-2012-%D0%BF#Text (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Zając, P.; Dębińska, E.; Maciuk, K. Accuracy of the evaluation of forest areas based on Landsat data using free software. Folia For. Pol. 2023, 65, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienciała, A.; Sobura, S.; Sobolewska-Mikulska, K. Optimising Land Consolidation by Implementing UAV Technology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashevskyi, M.; Malashevska, O. Land Consolidation Considering Natural Afforestation. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 2022, 16, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashevskyi, M.; Malashevska, O. The swapping approach in the course of land consolidation: Case study of Ukraine. Geod. Cartogr. 2021, 47, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, J. Participatory in Process, Inclusive in Outcomes: The PILaR approach to Land Readjustment. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Land Consolidation and Land Readjustment for Sustainable Development, Appeldoorn, The Netherlands, 9–11 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. The Law of Ukraine “On the State Land Cadastre”, Dated 7 July 2011, No 3613-VI. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/3613-17?lang=en#Text (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Dorosh, Y.; Barvinskyi, A.; Dorosh, A. Conceptual principles of formation of the system of rational agricultural land use. Zemleustriy Kadastr Monit. Zemel 2022, 1, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimeіchuk, I.; Kaidyk, O. Natural afforestation of the fallows in the Western Polissya. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2022, 13, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzanowski, B.; Kułaga, S.; Basista, I.; Borowski, Ł.; Maciuk, K. GIS Tools in the Conservation and Sustainable Development National Parks, Forests and Rural Areas. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2024, 15, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M.; Tesfaye, M.; Abdelkadir, A.; Abebaw, D.; Tanga, A.; Tesema, T.; Kassa, H. Impact of Forest Landscape Restoration (FLR) on rural households’ livelihood: The case of Sodo FLR, South Central Ethiopia. Int. J. Agric. Res. Innov. Technol. 2024, 13, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumer, P.; Potocnik Slavic, I. Heterogeneous small-scale forest ownership: Complexity of management and conflicts of interest. Belgeo 2016, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggermeier, A.; Koch, M.; Suda, M. Forest Land Consolidation—An analysis of importance and success criteria for implementation. Allg. Forst Jagdztg. 2011, 182, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Janus, J.; Ertunc, E. Towards a full automation of land consolidation projects: Fast land partitioning algorithm using the land value map. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, J.; Bożek, P.; Mitka, B.; Taszakowski, J.; Doroż, A. Long-term forest cover and height changes on abandoned agricultural land: An assessment based on historical stereometric images and airborne laser scanning data. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukaszewicz, J.; Krajewski, S. Reconstruction of forest areas on post−agricultural land in selected forest districts of State Forests in Poland based on archival maps. Sylwan 2023, 166, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basista, I. Application of GIS Tools to Describe the Location of New Registered Parcels. Geomat. Environ. Eng. 2020, 14, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basista, I.; Balawejder, M.; Kuchta, A. A land consolidation geoportal as a useful tool in land consolidation projects—A case study of villages in southern Poland. Acta Sci. Pol. Adm. Locorum 2023, 22, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T. Social Aspects in Land Consolidation Processes. Land 2022, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgan, M.; Bavorova, M. How to increase landowners’ participation in land consolidation: Evidence from North Macedonia. Land Use Policy 2022, 123, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lyu, D.; Sun, K.; Li, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, R.; Zheng, M.; Song, K. Spatiotemporal Analysis and War Impact Assessment of Agricultural Land in Ukraine Using RS and GIS Technology. Land 2022, 11, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Tenure Issue | Irrational Configuration | Full Natural Afforestation | Partial Natural Afforestation | Vague Legal Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before land consolidation | Quantity of land plots | 22 | 148 | 42 | 13 |

| % from the total quantity of land plots | 4.0 | 28.1 | 8.0 | 2.5 | |

| After land consolidation: Reallotment plan І | Quantity of land plots | 12 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| % from the total quantity of cases | 2.3 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.0 | |

| After land consolidation: Reallotment plan ІІ | Quantity of land plots | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| % from the total quantity of cases | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malashevskyi, M.; Kishchak, O.; Malashevska, O.; Kishchak, Y. Land Consolidation and Its Effects on Afforested Agricultural Land: A Case Study of Ukraine. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041517

Malashevskyi M, Kishchak O, Malashevska O, Kishchak Y. Land Consolidation and Its Effects on Afforested Agricultural Land: A Case Study of Ukraine. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041517

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalashevskyi, Mykola, Olena Kishchak, Olena Malashevska, and Yuriy Kishchak. 2025. "Land Consolidation and Its Effects on Afforested Agricultural Land: A Case Study of Ukraine" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041517

APA StyleMalashevskyi, M., Kishchak, O., Malashevska, O., & Kishchak, Y. (2025). Land Consolidation and Its Effects on Afforested Agricultural Land: A Case Study of Ukraine. Sustainability, 17(4), 1517. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041517