Consumer Sustainability: Is Knowledge Linked to Behavior in Recycling?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Research on Recycling Behavior

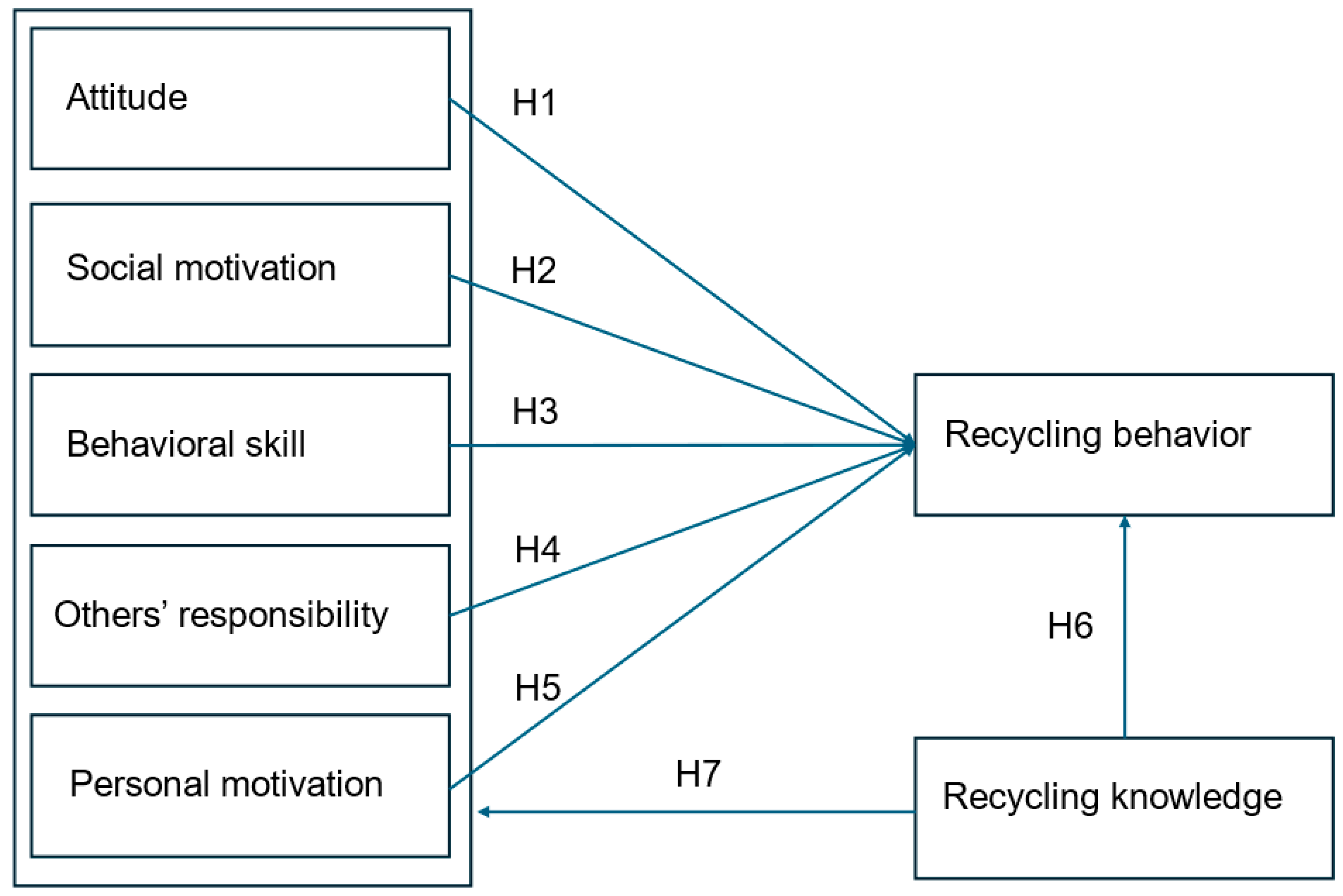

2.2. Conceptual Framework

2.3. Psychological Factors and Recycling Behavior

2.4. Recycling Knowledge and Recycling Behavior

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.3. Analyses

3.3.1. Sampling Weight

3.3.2. SEM Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

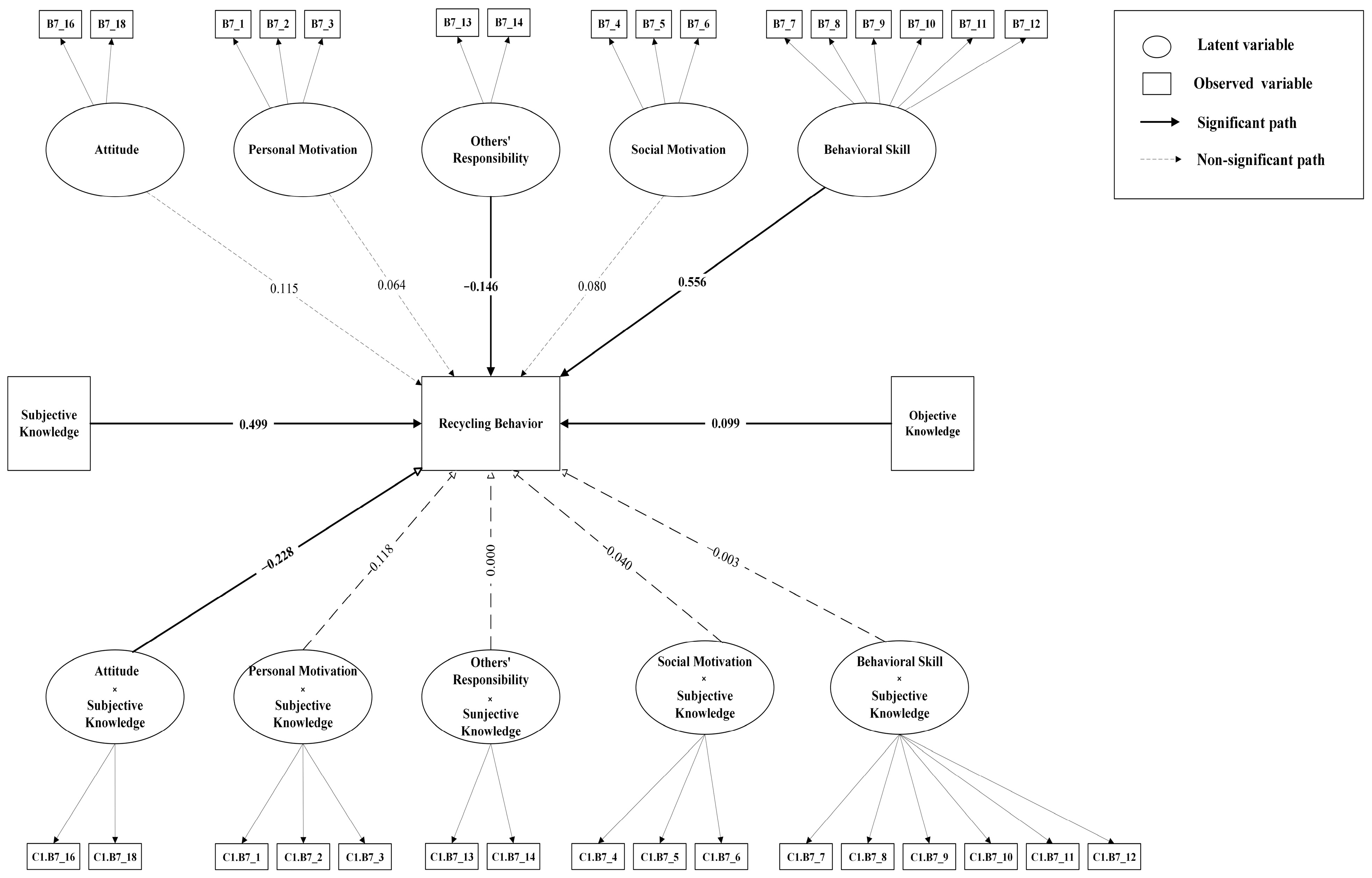

4.2. Analysis Model

5. Discussion, Limitations, and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Concari, A.; Kok, G.; Martens, P. Recycling behaviour: Mapping knowledge domain through bibliometrics and text mining. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 303, 114160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiger, J.L.; Steg, L.; Van Der Werff, E.; Ünal, A.B. A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 64, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, J.; Curtis, J.; Smith, L. Interdisciplinary, systematic review found influences on household recycling behaviour are many and multifaceted, requiring a multi-level approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2023, 18, 200152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulwani, P.R.; Kumar, D.; Goyal, P. A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis of recycling behavior. J. Glob. Mark. 2020, 33, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.Z. Predicting recycling behavior in New York state: An integrated model. Environ. Manag. 2022, 70, 1023–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fano, D.; Schena, R.; Russo, A. Empowering plastic recycling: Empirical investigation on the influence of social media on consumer behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arı, E.; Yılmaz, V. A proposed structural model for housewives’ recycling behavior: A case study from Turkey. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 129, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmaguc, T.; Kuštelega, M.; Kuštelega, M. The determinants of individual’s recycling behavior with an investigation into the possibility of expanding the deposit refund system in glass waste management in Croatia. Manag. J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2023, 28, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strydom, W.F. Applying the theory of planned behavior to recycling behavior in South Africa. Recycling 2018, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoo, A.C.; Tee, S.J.; Huam, H.T.; Mas’od, A. Determinants of recycling behavior in higher education institution. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1660–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, V.; Arı, E. Investigation of attitudes and behaviors towards recycling with theory planned behavior. J. Econ. Cult. Soc. 2022, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N.; Al-Hawari, M.A. Predictors of recycling behavior: The role of self-conscious emotions. J. Soc. Mark. 2021, 11, 204–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Khan, K.; Waris, I.; Zainab, B. Factors influencing the sustainable consumer behavior concerning the recycling of plastic waste. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2022, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Tseng, C.P.M.L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y. Intention in use recyclable express packaging in consumers’ behavior: An empirical study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Dreijerink, L.; Abrahamse, W. Factors influencing the acceptability of energy policies: A test of VBN theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships: A natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Huang, J.; Goyal, K.; Kumar, S. Financial capability: A systematic conceptual review, extension and synthesis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 1680–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.T.; Bumcrot, C.; Mottola, G.; Valdes, O.; Ganem, R.; Kieffer, C.; Lusardi, A.; Walsh, G. Financial Capability in the United States: Highlights from the FINRA Foundation National Financial Capability Study, 5th ed.; FINRA Investor Education Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.finrafoundation.org/sites/finrafoundation/files/NFCS-Report-Fifth-Edition-July-2022.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- RICCC. Survey of Consumer Recycling Behavior; Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation: Johnston, RI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, D.; Smith, T.M.F. Post stratification. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 1979, 142, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, S. Sampling: Design and Analysis; Duxbury Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Posit Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit Software; PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Mutha, R.; Kim, M. Frugal or Sustainable? The Interplay of Consumers’ Personality Traits and Self-Regulated Minds in Recycling Behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.J.; Tang, C.; Serido, J.; Shim, S. Antecedents and consequences of risky credit behavior among college students: Application and extension of the theory of planned behavior. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, D.; Dente, S.M.; Hashimoto, S. How Do Eco-Labels for Everyday Products Made of Recycled Plastic Affect Consumer Behavior? Sustainability 2024, 16, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Intention Predictors | Other Links | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Behavioral skill (PBC) + Ascription of responsibility + Personal norm + Personal motivation + Social motivation + Information +ns Emotion +ns | Intention, habit, personal norm->behavior Personal motivation, Social motivation, Information->behavioral skill Personal motivation, awareness of consequences->ascription of responsibility Ascription of responsibility, social motivation, awareness of consequences information->personal norm | 520 New York state residents |

| [6] | Attitude + Peer influence (SN) + Social media influence (SN) +ns PBC + | Sense of duty->attitude Convenience, cost->perceived control Intention->direct, indirect behavior | 467 Americans |

| [8] | Attitude − Subjective norm + PBC + | Intention->behavior | 400 housewives in Turkey |

| [9] | Attitude +ns Subjective norm + PBC + | Intention->behavior | 427 citizens in Croatia |

| [10] | Attitude + Subjective norm + PBC + | Intention->behavior PBC->behavior | 2004 consumers in South Africa |

| [11] | Attitude + Subjective norm + PBC + | Intention->behavior | 180 consumers in Malaysia |

| [12] | Attitude + Subjective norm + PBC + | Intention->behavior PBC->behavior | 205 respondents in Turkey |

| [13] | Appreciated guilt + Anticipated pride +ns Attitude −ns Subjective norm + Perceived effort (PBC) + Knowledge (PBC) + | Concern, consequences->guilt, pride Intention->behavior | 287 consumers in UAE using a two-wave survey |

| [14] | Attitude + Subjective norm + PBC + Normative social influence + Informational social influence + | Intention->behavior | 353 consumers in Karachi, Pakistan |

| [15] | Attitude + Subjective norm + PBC + Moral norm + Awareness of consequences + Convenience + | Intention, PBC-> behavior | 1303 respondents aged 18–35 in China |

| Personal motivation (α = 0.743) |

| 1. Finding room to store recyclable materials is a problem |

| 2. The problem with recycling is finding time to do it |

| 3. Storing recycling materials at home is unsanitary |

| Social motivation (α = 0.904) |

| 4. Most people who are important to me think I should recycle |

| 5. My household/family members think I should recycle |

| 6. My friends/colleagues think I should recycle |

| Behavioral skills (α = 0.913) |

| 7. I can recycle easily |

| 8. I have plenty of opportunities to recycle |

| 9. I have been provided satisfactory resources to recycle properly |

| 10. I know which materials/products are recyclable |

| 11. I know when and where I can recycle materials/products |

| Ascription of responsibility (α = 0.789) |

| 12. I am responsible for recycling properly (moved to behavioral skill) |

| 13. Government should be responsible for recycling properly |

| 14. Producers should be responsible for recycling properly |

| Attitude (α = 0.753) |

| 15. Recycling is a desirable behavior (removed) |

| 16. Recycling is not necessary |

| 17. Recycling is benefiting society (removed) |

| 18. Recycling has little benefit for individuals |

| Rotated Component Matrix a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item # | Component | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| 8 | 0.824 | 0.184 | 0.135 | −0.114 | −0.028 |

| 7 | 0.805 | 0.198 | 0.090 | −0.191 | −0.050 |

| 11 | 0.801 | 0.247 | 0.104 | −0.090 | −0.043 |

| 9 | 0.799 | 0.244 | 0.054 | −0.130 | 0.091 |

| 12 | 0.732 | 0.202 | 0.236 | −0.053 | −0.082 |

| 10 | 0.634 | 0.161 | 0.245 | −0.094 | −0.129 |

| 6 | 0.318 | 0.859 | 0.156 | −0.037 | −0.020 |

| 4 | 0.290 | 0.842 | 0.077 | 0.024 | −0.031 |

| 5 | 0.359 | 0.824 | 0.150 | −0.045 | −0.090 |

| 13 | 0.121 | 0.036 | 0.855 | 0.030 | 0.077 |

| 14 | 0.176 | 0.151 | 0.848 | −0.026 | 0.037 |

| 17 | 0.434 | 0.166 | 0.524 | 0.012 | −0.419 |

| 15 | 0.446 | 0.221 | 0.513 | −0.047 | −0.234 |

| 1 | −0.189 | 0.014 | 0.035 | 0.804 | 0.003 |

| 3 | −0.090 | −0.071 | −0.011 | 0.785 | 0.155 |

| 2 | −0.108 | 0.012 | −0.037 | 0.773 | 0.212 |

| 16 | −0.055 | −0.041 | −0.061 | 0.185 | 0.857 |

| 18 | −0.027 | −0.031 | 0.066 | 0.167 | 0.854 |

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | z-Value | p-Value | Std. All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 0.144 | 0.083 | 1.737 | 0.082 | 0.115 |

| Personal Motivation | 0.106 | 0.097 | 1.095 | 0.273 | 0.064 |

| Social Motivation | 0.115 | 0.074 | 1.549 | 0.121 | 0.080 |

| Others’ Responsibility | −0.226 | 0.088 | −2.552 | 0.011 | −0.146 |

| Behavioral Skill | 0.771 | 0.078 | 9.943 | <0.001 | 0.556 |

| Objective Knowledge | 0.054 | 0.027 | 2.046 | 0.041 | 0.099 |

| Subjective Knowledge | 0.358 | 0.033 | 10.691 | <0.001 | 0.499 |

| Attitude × Knowledge | −0.165 | 0.048 | −3.415 | 0.001 | −0.228 |

| Personal Motivation × Subj Knowledge | −0.097 | 0.053 | −1.817 | 0.069 | −0.118 |

| Others’ Responsibility × Subj Knowledge | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.004 | 0.997 | 0.000 |

| Social Motivation × Subj Knowledge | −0.031 | 0.037 | −0.832 | 0.405 | −0.040 |

| Behavioral Skill × Subj Knowledge | −0.002 | 0.051 | −0.044 | 0.965 | −0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.J.; Rafiee, P.; Xia, F.; Wu, J. Consumer Sustainability: Is Knowledge Linked to Behavior in Recycling? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041498

Xiao JJ, Rafiee P, Xia F, Wu J. Consumer Sustainability: Is Knowledge Linked to Behavior in Recycling? Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041498

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jing Jian, Parisa Rafiee, Feihong Xia, and Jing Wu. 2025. "Consumer Sustainability: Is Knowledge Linked to Behavior in Recycling?" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041498

APA StyleXiao, J. J., Rafiee, P., Xia, F., & Wu, J. (2025). Consumer Sustainability: Is Knowledge Linked to Behavior in Recycling? Sustainability, 17(4), 1498. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041498

_Li.png)