Challenges to Inclusive and Sustainable Societies: Exploring the Polarizing Potential of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Forms of Living in Austria, Italy, Poland, and Sweden

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Polarization—A State-of-the-Art Review and the Role of General Versus Specific Commitment

3. Determinants of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Ways of Life and Country Selection

3.1. Age

3.2. Gender

3.3. Education

3.4. Left-Right Ideology

3.5. Residential Background: Urban-Rural Divide

- Older respondents are less often worried about climate change and have lower tolerance towards non-heteronormative ways of life.

- In general, female respondents report more awareness of climate change and show more tolerance for non-heteronormative ways of life compared to men.

- Respondents with higher education levels more often perceive climate change as worrisome and report higher tolerance towards non-heteronormative ways of life.

- We expect only minor effects of place of residence (urban-rural), with urban residents more open towards non-heteronormative ways of life and more worried about climate change.

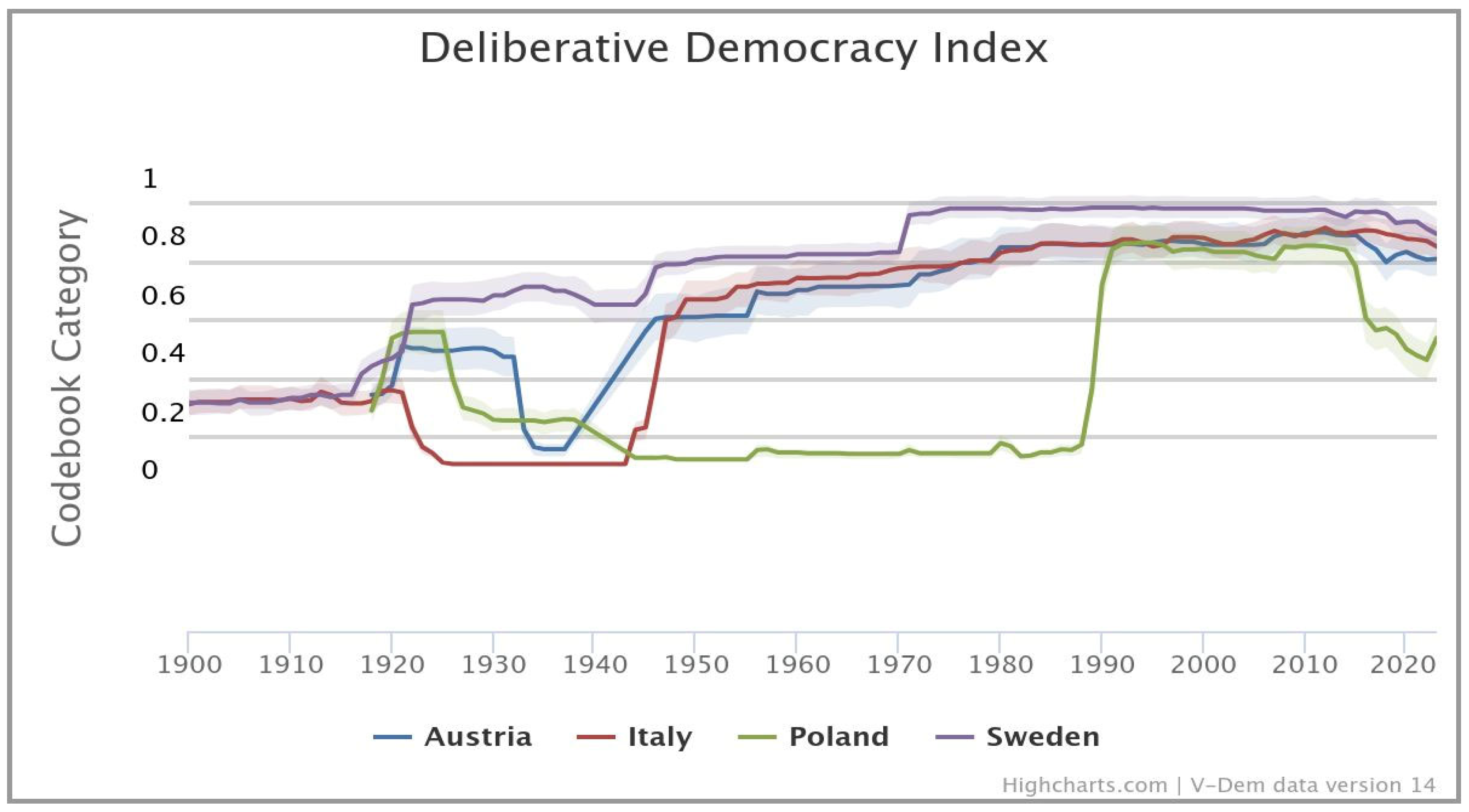

3.6. Country Selection

4. Method: Data, Analytical Strategy, and Statistical Analysis

4.1. Analytical Strategy

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Findings

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| AT (n = 2003) | IT (n = 2640) | SE (n = 2280) | PL (n = 2065) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 52.92 | 53.76 | 55.09 | 51.04 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 48.7 | 47.5 | 48.2 | 48.3 |

| Female | 51.3 | 52.5 | 51.8 | 51.7 |

| Education | ||||

| ES-ISCED I, less than lower secondary | 1.7 | 9.1 | 7.9 | 0.6 |

| ES-ISCED II, lower secondary | 7.9 | 28.2 | 12.5 | 29.6 |

| ES-ISCED IIIb, lower tier upper secondary | 32.8 | 7.5 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| ES-ISCED IIIa, upper tier upper secondary | 6.7 | 33.0 | 16.4 | 22.0 |

| ES-ISCED IV, advanced vocational, sub-degree | 23.7 | 5.1 | 22.3 | 5.0 |

| ES-ISCED V1, lower tertiary education, BA level | 8.0 | 6.2 | 14.5 | 8.2 |

| ES-ISCED V2, higher tertiary education, ≥MA level | 18.6 | 10.7 | 15.9 | 21.9 |

| Other | 0.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| Domicile | ||||

| A big city | 16.9 | 8.9 | 18.6 | 23.6 |

| Suburbs or outskirts of big city | 15.7 | 3.3 | 23.5 | 5.1 |

| Town or small city | 22.7 | 41.4 | 33.0 | 34.1 |

| Country village | 34.1 | 43.8 | 14.5 | 33.6 |

| Farm or home in the countryside | 10.6 | 2.7 | 10.4 | 3.6 |

| Education x Domicile | Income x Domicile | |

|---|---|---|

| Austria | 0.135 *** | 0.080 ** |

| Italy | 0.090 *** | 0.060 |

| Sweden | 0.108 *** | 0.076 *** |

| Poland | 0.186 *** | 0.134 *** |

References

- Arbatli, E.; Rosenberg, D. United We Stand, Divided We Rule: How Political Polarization Erodes Democracy. Democratization 2021, 28, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Evans, J.; Bryson, B. Have American’s Social Attitudes Become More Polarized? Am. J. Sociol. 1996, 102, 690–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Lelkes, Y.; Levendusky, M.; Malhotra, N.; Westwood, S.J. The Origins and Consequences of Affective Polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2019, 22, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. Affective Polarization in Europe. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2024, 16, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelkes, Y. Mass Polarization: Manifestations and Measurements. Public Opin. Q. 2016, 80, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarri, D.; Bearman, P. Dynamics of Political Polarization. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 784–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mau, S.; Lux, T.; Westheuser, L. Triggerpunkte Konsens und Konflikt in der Gegenwartsgesellschaft, 1st ed.; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3-518-77676-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kulin, J.; Sevä, I.J.; Dunlap, R.E. Nationalist Ideology, Rightwing Populism, and Public Views about Climate Change in Europe. Environ. Political 2021, 30, 1111–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.B.; Palm, R.; Feng, B. Cross-National Variation in Determinants of Climate Change Concern. Environ. Political 2019, 28, 793–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teney, C.; Pietrantuono, G.; Wolfram, T. What Polarizes Citizens? An Explorative Analysis of 817 Attitudinal Items from a Non-Random Online Panel in Germany. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, D. What Do You Think About Climate Change? J. Econ. Surv. 2023, 37, 1255–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, J.; Steinhilper, E. Politische Polarisierung: Zur Systematisierung Eines Vielschichtigen Konzepts. Forschungsjournal Soz. Beweg. 2022, 35, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, T.; Mau, S.; Jacobi, A. Neue Ungleichheitsfragen, neue Cleavages? Ein internationaler Vergleich der Einstellungen in vier Ungleichheitsfeldern. Berl. J. Soziol. 2022, 32, 173–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, D.J. Polarization and Persuasion: Engaging Sociology in the Moral Universe of a Divided Democracy. Sociol. Perspect. 2022, 65, 1029–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Qian, H.; Houser, M.K.; McCright, A.M. Climate Change Views, Energy Policy Preferences, and Intended Actions Across Welfare State Regimes: Evidence from the European Social Survey. Int. J. Sociol. 2019, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, G.M.D.; Quaranta, M. Let Them Be, Not Adopt: General Attitudes Towards Gays and Lesbians and Specific Attitudes Towards Adoption by Same-Sex Couples in 22 European Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Baldassarri, D.S.; Druckman, J.N. Cognitive–Motivational Mechanisms of Political Polarization in Social-Communicative Contexts. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 1, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, D.; Habed, A.J.; Henninger, A. (Eds.) Blurring Boundaries—“Anti-Gender” Ideology Meets Feminist and LGBTIQ+ Discourses, 1st ed.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3-8474-2684-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar, R.; Paternotte, D. “Gender Ideology” in Movement: Introduction. In Anti-gender campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing Against Equality; Kuhar, R., Paternotte, D., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd.: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-78348-999-2. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, J.; Scheele, A.; Winkel, H. (Eds.) Global Contestations of Gender Rights; BiUP General; Bielefeld University Press: Bielefeld, Germany, 2022; ISBN 978-3-8394-6069-6. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, A.; Gugushvili, D. Eco-Social Divides in Europe: Public Attitudes towards Welfare and Climate Change Policies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, C.; Halikiopoulou, D.; Vrakopoulos, C. The Centre-Periphery Divide and Attitudes towards Climate Change Measures among Western Europeans. Environ. Political 2023, 32, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, T.; Doran, R.; Böhm, G.; Tvinnereim, E.; Poortinga, W. Political Orientation Moderates the Relationship Between Climate Change Beliefs and Worry About Climate Change. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, J.; Szalma, I.; Bartus, T. Social Attitudes Toward Adoption by Same-Sex Couples in Europe. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2016, 45, 1787–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammaturo, F.R.; Slootmaeckers, K. The Unexpected Politics of ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Maps: (De)Constructing Queer Utopias/Dystopias. Eur. J. Political Gend. 2024, 8, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, A.; Davidov, E.; Schwartz, S.H.; Schmidt, P. Human Values, Legal Regulation, and Approval of Homosexuality in Europe: A Cross-country Comparison. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dochow-Sondershaus, S.; Teney, C.; Borbáth, E. Cultural Backlash? Trends in Opinion Polarisation between High and Low-Educated Citizens since the 1980s: A Comparison of France, Italy, Hungary, Poland and Sweden. SocArXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenberg, T.; Scheepers, P. Rejection of Equal Adoption Rights for Same-sex Couples across European Countries: Socializing Influences on the National Level and Cross-national Interactions. Soc. Sci. Q. 2022, 103, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettinsoli, M.L.; Suppes, A.; Napier, J.L. Predictors of Attitudes Toward Gay Men and Lesbian Women in 23 Countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Akker, H.; Van Der Ploeg, R.; Scheepers, P. Disapproval of Homosexuality: Comparative Research on Individual and National Determinants of Disapproval of Homosexuality in 20 European Countries. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2013, 25, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takács, J.; Szalma, I. Democracy Deficit and Homophobic Divergence in 21st Century Europe. Gend. Place Cult. 2020, 27, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, E.; Trop, T. Environmental Attitudes and Environmental Behavior—Which Is the Horse and Which Is the Cart? Sustainability 2012, 4, 2210–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seker, S.; Sahin, E.; Hacıeminoğlu, E.; Demirci, S. Do Teenagers Believe in Anthropogenic Climate Change and Take Action to Tackle It? Sustainability 2024, 16, 7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricart, S.; Olcina, J.; Rico, A.M. Evaluating Public Attitudes and Farmers’ Beliefs towards Climate Change Adaptation: Awareness, Perception, and Populism at European Level. Land 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félonneau, M.-L.; Becker, M. Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behavior: Revealing Perceived Social Desirability. Rev. Int. Psychol. Soc. 2008, 21, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A. Sustainability Skepticism: Attitudes to, and Beliefs about, Climate Change. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.F. Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations Are Changing, and Reshaping the World, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-108-61388-0. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, A.; Meyer, R. Environmental Attitudes in Cross-National Perspective: A Multilevel Analysis of the ISSP 1993 and 2000. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Right-Wing Populism and the Climate Change Agenda: Exploring the Linkages. Environ. Political 2018, 27, 712–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godø, T.B.; Bjørndal, Å.; Fluge, I.M.; Johannessen, R.; Lavdas, M. Personality Traits, Ideology, and Attitudes Toward LGBT People: A Scoping Review. J. Homosex. 2024, 8, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, P.; Stoeckl, K. The Global Resistance to LGBTIQ Rights. J. Democr. 2024, 35, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosun, J.; Debus, M. Right-Wing Populist Parties and Environmental Politics: Insights from the Austrian Freedom Party’s Support for the Glyphosate Ban. Environ. Political 2021, 30, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunklinger, M.; Ajanović, E. Voting Right? Analyzing Electoral Homonationalism of LGBTIQ* Voters in Austria and Germany. Soc. Political Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2022, 29, 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A.R. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right; New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-62097-225-0. [Google Scholar]

- Huijsmans, T.; Harteveld, E.; Van Der Brug, W.; Lancee, B. Are Cities Ever More Cosmopolitan? Studying Trends in Urban-Rural Divergence of Cultural Attitudes. Political Geogr. 2021, 86, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zürn, M.; De Wilde, P. Debating Globalization: Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism as Political Ideologies. J. Political Ideol. 2016, 21, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teney, C.; Lacewell, O.P.; De Wilde, P. Winners and Losers of Globalization in Europe: Attitudes and Ideologies. Eur. Political Sci. Rev. 2014, 6, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.J.; Ryan, R.L. Place Attachment and Landscape Preservation in Rural New England: A Maine Case Study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenbrink, T.; Willcock, S. Place Attachment and Perception of Climate Change as a Threat in Rural and Urban Areas. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitter, H.; Larcher, M.; Schönhart, M.; Stöttinger, M.; Schmid, E. Exploring Farmers’ Climate Change Perceptions and Adaptation Intentions: Empirical Evidence from Austria. Environ. Manag. 2019, 63, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. Are Urban Spaces Queer-Friendly Places? How Geographic Context Shapes Support for LGBT Rights. OSF Preprints 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. Rural Identity and LGBT Public Opinion in the United States. Public Opin. Q. 2023, 87, 956–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. The Limits to Scale? Methodological Reflections on Scalar Structuration. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2001, 25, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podmore, J.A.; Bain, A.L. Whither Queer Suburbanisms? Beyond Heterosuburbia and Queer Metronormativities. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 1254–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiljan, A.; Ryan, A. Ideological Tripolarization, Partisan Tribalism and Institutional Trust: The Foundations of Affective Polarization in the Swedish Multiparty System. Scand. Political Stud. 2021, 44, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A. Left–Right Ideology as a Dimension of Identification and of Competition. J. Political Ideol. 2015, 20, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G.; Wilson, C.J. Does Left/Right Structure Party Positions on European Integration? Comp. Political Stud. 2002, 35, 965–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weko, S. Communitarians, Cosmopolitans, and Climate Change: Why Identity Matters for EU Climate and Energy Policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2022, 29, 1072–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, A.; Thérien, J.-P.; Boucher, É. The Political Construction of the Left-Right Divide: A Comparative Perspective. J. Political Ideol. 2021, 26, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directorate General for Climate Action. In Climate Change: Report Summary; Special Eurobarometer; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). ESS10 Integrated File, Edition 3.2; [Data Set]; Sikt-Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research: Trondheim, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Social Survey European Research Infrastructure (ESS ERIC). 2023. ESS10 Self-Completion—Integrated File, Edition 3.1; [Data Set]; Sikt-Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research: Trondheim, Norway, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucetich, J.A.; Bruskotter, J.T.; Ghasemi, B.; Rapp, C.E.; Nelson, M.P.; Slagle, K.M. A Flexible Inventory of Survey Items for Environmental Concepts Generated via Special Attention to Content Validity and Item Response Theory. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, R.; Klösch, B.; Hadler, M. Umwelt in der Krise. Einstellungen zu Klimawandel und Umweltbesorgnis sowie Bereitschaft zu umweltbewusstem Verhalten in Krisenzeiten. In Die Österreichische Gesellschaft Während der Corona-Pandemie; Aschauer, W., Glatz, C., Prandner, D., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2022; pp. 241–267. ISBN 978-3-658-34490-0. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn, J. Stadt und Land in der Klimakrise: Gemeinsamer Blickwinkel oder Divergierende Perspektiven? Politische Einstellungen in Verschiedenen Wohnorts—Umfeldern—von Ländlichen bis Städtischen Räumen; böll.brief Demokratie & Gesellschaft; Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps, N.A. Introduction: Old Europe, New Suburbanization? In Old Europe, New Suburbanization? Governance, Land, and Infrastructure in European Suburbanization; Phelps, N.A., Ed.; Global Suburbanisms; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada; Buffalo, NY, USA; London, UK, 2017; pp. 3–17. ISBN 978-1-4426-4826-5. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, R. Suburbanization and Suburbanism. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 660–666. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arıkan, G.; Günay, D. Public Attitudes towards Climate Change: A Cross-Country Analysis. Br. J. Political Int. Relat. 2021, 23, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, J. Eine Tief Abgespaltene Minderheit: Polarisierungstendenzen in Deutschland. Forschungsjournal Soz. Beweg. 2022, 35, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, M. Issue Politicization and Social Class: How the Electoral Supply Activates Class Divides in Political Preferences. Eur. J. Political Res. 2022, 61, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.; Attewell, D.; Rovny, J.; Hooghe, L. Cleavage Theory. In The Palgrave Handbook of EU Crises; Riddervold, M., Trondal, J., Newsome, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 173–193. ISBN 978-3-030-51790-8. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Die Gesellschaft der Singularitäten: Zum Strukturwandel der Moderne, 1st ed.; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-518-58706-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cecilia, R.; Guijarro-Ojeda, J.R.; Marín-Macías, C. Analysis of Heteronormativity and Gender Roles in EFL Textbooks. Sustainability 2021, 13, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Daily, A.E.; Harris, R.; Sebares-Valle, G.; Sabido-Codina, J. Revisiting Past Experiences of LGBTQ+-Identifying Students: An Analysis Framed by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppedge, M.; Gerring, J.; Knutsen, C.H.; Lindberg, S.I.; Teorell, J.; Marquardt, K.L.; Medzihorsky, J.; Pemstein, D.; Fox, L.; Gastaldi, L.; et al. V-Dem Dataset. V14; V-Dem Institute: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Sweden | Austria | Italy | Poland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal democracy index 2021 (Index based on expert ratings evaluating the protection of civil liberties, the strength of the rule of law, the independence of judiciary, the effectiveness of checks and balances and the level of electoral democracy; range: 0 to 1 (most democratic) (https://www.v-dem.net/, (accessed on 1 August 2024))) | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.41 |

| ILGA rainbow map index 2022 (75 criteria in seven areas: equality and non-discrimination, family, hate crime and hate speech, legal gender recognition, intersex bodily integrity, civil society space and asylum; expert ratings; range from 0% (gross violations of human rights, discrimination) to 100% (respect of human rights, full equality)) | 67.98 | 48.18 | 24.76 | 13.07 |

| Eurobarometer 493 (2019): Same rights for LGBTIQ persons (% agreement) (Item wording: “Gay, lesbian and bisexual persons should have the same rights as heterosexual persons”) | 98 | 70 | 68 | 49 |

| Climate Change Performance Index CCIP 2021 (Index based on 14 indicators in four areas by official documents and expert ratings: greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energies, energy use and climate policy; higher values reflect a good performance of a country in addressing climate change developments. This index is widely used in academic research (https://ccpi.org/impact/#34, (accessed on 1 August 2024)) and ranges from 0 to 100.) | 74.42 | 48.09 | 53.05 | 38.94 |

| Eurobarometer 513 (2021): (Item wording: And how serious a problem do you think climate change is at this moment? Please use a scale from 1 to 10, with ‘1’ meaning it is “not at all a serious problem” and ‘10’ meaning it is “an extremely serious problem”.) climate change very serious (% agreement 7–10 points) | 79 | 69 | 84 | 69 |

| Attitudes Towards Non-Heteronormative Ways of Life High Support | Attitudes Towards Non-Heteronormative Ways of Life Low Support | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitudes towards climate change High Awareness | High support/high awareness | Low support/high awareness |

| Attitudes towards climate change Low Awareness | High support/low awareness | Low support/low awareness |

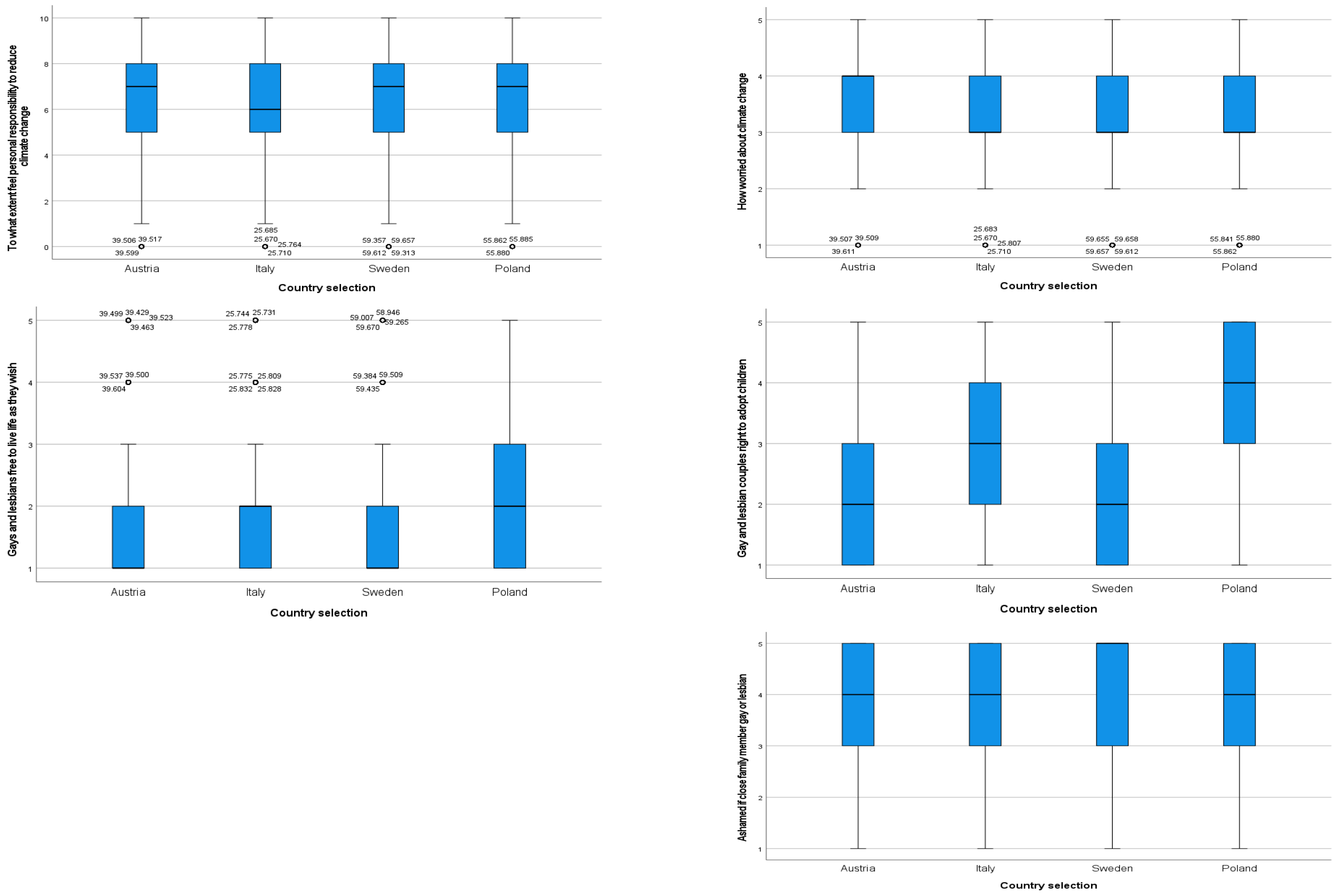

| Original Variable | Recoded Variable |

|---|---|

| Gay men and lesbians should be free to live their own lives as they wish. (1: Agree strongly; 2: Agree; 3: Neither agree nor disagree; 4: Disagree; 5: Disagree strongly) | The response scale was inverted. |

| Gay male and lesbian couples should have the same rights to adopt children as straight couples. (1: Agree strongly; 2: Agree; 3: Neither agree nor disagree; 4: Disagree; 5: Disagree strongly) | The response scale was inverted. |

| If a close family member was a gay man or a lesbian, I would feel ashamed. (1: Agree strongly; 2: Agree; 3: Neither agree nor disagree; 4: Disagree; 5: Disagree strongly) | Not recoded. |

| To what extent do you feel a personal responsibility to try to reduce climate change? (11-point scale with the endpoints 0: Not at all and 10: A great deal) | Based on a previous filter, the question was posed only to those who think that climate change is happening. The value of 0 was assigned to those who don’t believe this. Then the scale was transformed with the formula (X + 2.5)/2.5 to a 1 to 5 format. |

| How worried are you about climate change? (1: Not at all worried; 2: Not very worried; 3: Somewhat worried; 4: Very worried; 5: Extremely worried) | Based on a previous filter, the question was posed only to those who think that climate change is happening. The value of 1 was assigned to those who don’t believe this. |

| Attitudes Towards Non-Heteronormative Ways of Life (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.78) | Attitudes Towards Climate Change (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.73) | Communality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gays and lesbians are free to live life as they wish | 0.87 | −0.02 | 0.74 |

| Gay and lesbian couples right to adopt children | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0.51 |

| Ashamed if a close family member is gay or lesbian | 0.7 | 0.01 | 0.49 |

| Personal responsibility to reduce climate change | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.58 |

| Worried about climate change | −0.01 | 0.76 | 0.57 |

| Group 1: Low/Low | Group 2: Only High Support, Non-Het. Ways of Life | Group 3: Only High Awareness of Climate Change | Group 4: High/High | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria (n = 2003) | 17.57 | 18.32 | 18.72 | 41.94 | 3.44 |

| Italy (n = 2640) | 31.02 | 13.45 | 24.02 | 23.11 | 8.41 |

| Poland (n = 2065) | 32.98 | 8.72 | 31.57 | 21.21 | 5.52 |

| Sweden (n = 2287) | 15.13 | 25.54 | 11.94 | 45.52 | 1.88 |

| All (n = 8995) | 24.44 | 16.52 | 21.50 | 32.56 | 4.98 |

| Group 1: Low/Low | Group 2: Only High Support, Non-Het. Ways of Life | Group 3: Only High Awareness of Climate Change | Group 4: High/High | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A big city | 17.91 | 18.48 | 19.39 | 44.22 |

| Suburbs or outskirts of a big city | 18.28 | 23.03 | 15.45 | 43.23 |

| Town or small city | 28.17 | 16.91 | 22.08 | 32.84 |

| Country village | 29.99 | 14.56 | 27.76 | 27.69 |

| Farm or home in the countryside | 24.56 | 20.11 | 20.64 | 34.70 |

| Group 2: Only High Support, Non-Het. Ways of Life | Group 3: Only High Awareness of Climate Change | Group 4: High/High | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR2 | SE2 | p-val2 | OR3 | SE3 | p-val3 | OR4 | SE4 | p-val4 | |

| Intercept | 3.49 | 0.170 | 0.000 | 0.58 | 0.168 | 0.001 | 3.49 | 0.154 | 0.000 |

| Gender (ref. male) | |||||||||

| Female | 1.47 | 0.073 | 0.000 | 1.30 | 0.065 | 0.000 | 2.29 | 0.064 | 0.000 |

| Domicile (ref. city) | |||||||||

| Town, village, farm | 0.68 | 0.085 | 0.000 | 0.92 | 0.081 | 0.292 | 0.62 | 0.075 | 0.000 |

| Education (ref. ISCED I/II) | |||||||||

| ISCED III | 1.53 | 0.095 | 0.000 | 1.22 | 0.080 | 0.013 | 2.03 | 0.086 | 0.000 |

| ISCED IV and V | 1.98 | 0.099 | 0.000 | 1.61 | 0.086 | 0.000 | 4.01 | 0.088 | 0.000 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 1.00 | 0.002 | 0.016 | 0.97 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Country (ref. Austria) | |||||||||

| Italy | 0.51 | 0.107 | 0.000 | 0.88 | 0.098 | 0.180 | 0.44 | 0.092 | 0.000 |

| Poland | 0.24 | 0.121 | 0.000 | 1.04 | 0.098 | 0.688 | 0.28 | 0.098 | 0.000 |

| Sweden | 1.90 | 0.108 | 0.000 | 0.77 | 0.115 | 0.024 | 1.46 | 0.097 | 0.000 |

| CoxSnell | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Nagelkerke | 0.24 | ||||||||

| McFadden | 0.10 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Donat, E.; Mataloni, B.; Ajanovic, E. Challenges to Inclusive and Sustainable Societies: Exploring the Polarizing Potential of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Forms of Living in Austria, Italy, Poland, and Sweden. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041457

Donat E, Mataloni B, Ajanovic E. Challenges to Inclusive and Sustainable Societies: Exploring the Polarizing Potential of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Forms of Living in Austria, Italy, Poland, and Sweden. Sustainability. 2025; 17(4):1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041457

Chicago/Turabian StyleDonat, Elisabeth, Barbara Mataloni, and Edma Ajanovic. 2025. "Challenges to Inclusive and Sustainable Societies: Exploring the Polarizing Potential of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Forms of Living in Austria, Italy, Poland, and Sweden" Sustainability 17, no. 4: 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041457

APA StyleDonat, E., Mataloni, B., & Ajanovic, E. (2025). Challenges to Inclusive and Sustainable Societies: Exploring the Polarizing Potential of Attitudes Towards Climate Change and Non-Heteronormative Forms of Living in Austria, Italy, Poland, and Sweden. Sustainability, 17(4), 1457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17041457