Abstract

Co-production is viewed as a solution to deal with societal issues. For instance, citizens are encouraged to propose solutions and work together with the government to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. We have a solid understanding of the initial phase of co-production and the factors that influence this phase, such as motivation, resources, social capital, and a supportive culture. There is consensus in the literature that co-production initially exists between the state and the community. However, we still know relatively little about the connection between these factors and the development and the orientation of co-production. This narrative review examines the current understanding of shifts in co-production orientation. This study employs an analysis and synthesis of data derived from 76 peer-reviewed articles sourced from academic databases. The objective is to present a comprehensive conceptual model. We argue that these factors shape how co-production develops after the initial phase, potentially shifting its position between the domains of state, community, and market. Factors tend to push the orientation of co-production in the direction of the community, but not exclusively so. To better understand these dynamics, qualitative longitudinal research should be conducted to trace the interactions between and within the factors that influence co-production orientation.

1. Introduction

Societies face significant transitions to a climate-neutral society, which will require citizens’ active engagement in problem-solving [1]. Numerous examples of citizen initiatives that collaborate with local government already exist, such as the establishment of citizen-led energy corporations to generate sustainable energy or initiatives where citizens advise their neighbors on energy-saving methods. Co-production is one of the concepts used to describe the engagement of citizens in the development or delivery of policies. In the context of energy transition, this collaboration will intensify over the long term because we have set a goal to be energy neutral by 2050 and citizens should be involved in the process, creating a sense of joint responsibility as also formulated in the SDGs of the UN [2]. Co-production is one of the concepts that signifies this engagement of citizens in the development or delivery of policies. However, we do not know how this collaboration will endure. The co-production literature falls short of addressing this longitudinal collaboration and the developments that occur over time.

The literature discusses the role of several factors related to co-production, such as motivation, resources, social capital, and a supportive culture. These factors affect the effectiveness of co-production but also its location between the state, the market, and civil society. The positioning of co-production among these dimensions is what we call the orientation of co-production. Focusing on orientation highlights how responsibility is distributed within a collaboration, providing insight into how co-production can be leveraged to address societal issues.

We assume that co-production in its initial phase is typically located in between the state and civil society. Changes in orientation can take place over time; however, the factors affecting the initial orientation of co-production can change during co-production, and other factors may come into play. For instance, a citizen-led energy corporation can be influenced by resources from a for-profit energy company that might steer the co-production more toward the market domain.

As our understanding of the development of co-production orientation is limited, this article presents the results of a narrative review of the current literature. Based on the literature, it identifies several research gaps in the literature but also suggests that existing insights can be used in a different way to develop a new conceptual model to fill these gaps [3].

The overarching research question for this article is the following: What is currently understood in the co-production literature regarding the shifts in co-production orientation, and how can we comprehensively analyze these developments?

The conceptual model that is developed in this article allows us to better understand the orientation of co-production by turning to several dimensions. Doing so is needed to gain a more detailed understanding of the changes in orientation that take place over time. These different dimensions, in addition, can also be linked more clearly to several factors influencing co-production that are already discussed in the literature. This makes it possible to develop several expectations about how different factors influence the orientation dimensions.

Since the co-production literature is primarily comprised of case studies, of single moments in the development of co-production instead of the overall process [4,5], we do not know how it develops from the initial phase. As a result, we lack a good understanding of what possible developments in co-production can occur over time.

The urgency for citizens’ participation is increasing. However, we do not know how it settles after the start. The tools to evaluate co-production are limited due to the lack of a comprehensive approach or to pitfalls in the research design, like a high number of dropouts for quantitative longitudinal research [6]. To evaluate co-production, it is necessary to know how the collaboration between local government and citizens endures and how various factors related to co-production interact and affect orientation. This study takes the existing literature a step further with this narrative review by presenting a conceptual model that helps to evaluate the concept of co-production, especially in the long term, and its orientation by taking a more holistic approach to related co-production factors and orientation.

This is in line with a broader debate surrounding the use of co-production in the literature. An increasing number of scholars have identified potential disadvantages associated with co-production [7,8]. These include concerns about the level of democracy and the focus on private or social benefits rather than the public benefits that the work of the government should prioritize [6]. When we know more about orientation and the development that takes place, we can also evaluate the concept of co-production better. Does the development match the expectations we have of co-production?

Furthermore, the findings of this study are of relevance to those engaged in the practical and policy-making aspects of co-production. An awareness of the differences in orientation can facilitate a strategic approach by the government and assist in the development of co-production in a specific orientation. This article begins by reviewing the definition of co-production, highlighting its varied usage and the multiple definitions that exist across different contexts (Section 2). Although co-production has been conceptualized in various ways, these differences are often minor. In this section, we aim to establish a common understanding and definition that are useful for seeing co-production as a long-term process. We proceed to discuss the rationale behind the choice of narrative review design and the methods and materials employed in conducting the review in order to demonstrate its suitability for achieving the research aim (Section 3). Next, in the results section, we describe the potential orientations of co-production, which typically begin between the state and the civil society domains but may evolve into one of these domains or shift toward a new domain, such as that of the market (Section 4). Following this, we elaborate on the factors—motivation, resources, social capital, and a supportive culture—and examine how they influence the orientation of co-production. In the subsequent section, we delve deeper into the dynamics that may create tension in the development of orientation. Finally, we conclude by discussing the findings of this article in the broader context of the ongoing debate in the co-production literature (Section 5 and Section 6).

The research objective of this narrative review is to theoretically explore the relationship between a number of factors—motivation, resources, social capital, and a supportive culture—and the orientation of co-production, leading to several theoretical expectations presented in a comprehensive conceptual model that is a starting point for further empirical research.

2. Co-Production: A Conceptual Review

The term ‘co-production’ is employed for a wide range of areas and activities [9,10]. Many argue that co-production is about citizens’ active engagement or involvement in public service delivery [11,12,13]. Citizens’ input, especially in the climate transition, is considered a crucial element in the service delivery process: public sector organizations incorporate this input to achieve their objectives [9]. Co-production is thus a means to create public goods or public services, although some speak more broadly about attaining public values [14,15].

The actors involved in co-production can be divided into the state/regular producer and co-producing citizens [9]. The regular producer is often a local government or a public organization responsible for providing public services. Especially when it comes to the climate transition, most initiatives will occur at the local level and therefore automatically involve local government [16].

The co-producing citizens involved in co-production are more diverse. Co-production research has identified various types of citizens. One type is volunteers, who typically approach co-production with an altruistic mindset, aiming to contribute to a better world in general [17]. Another type is ‘clients’. This term is frequently used to describe co-producing citizens who pursue private values and have a formal relationship with the government [18]. Lastly, the term ‘citizens’ is used in the context of co-production, referring to a collective ‘we’ and social values. Empirical co-production research has identified different typologies of co-producing citizens, representing various characteristics of volunteers, clients, and citizens [17]. Whether for-profit and semi-profit organizations can be classified as co-producers as well is still debated [19]. Here, we will exclude them from our review of co-production, although it is possible that they come to play a role over the course of its development. We view co-production at the start in a stricter sense, in which citizens and (representatives of) public organizations both make a substantial contribution to public service delivery [20,21].

The concept of co-production is placed on one of the higher rungs of citizen participation by Arnstein [22]. As one of the founders of the conceptualization of citizen participation, Arnstein indicated that co-production represents a form of true citizen power, where citizens collaborate with public institutions, sharing power to the extent that both actors have a say. In this context, the ‘co’ of co-production stands for collaboration. To what extent powers are equally shared for co-production depends also on the position of the government on the ladder of governmental participation [23]. Co-production is situated somewhere on a spectrum ranging from citizens being almost fully responsible for outcomes to being a crucial but small part of a network of actors in which citizens have the power to influence decision-making through direct participation.

The timing of the collaboration in the policy cycle, however, is not as clear as some scholars might argue. Some scholars also include the planning phase or the policy-making process as part of co-production, particularly when the nature of co-production is highly technical, such as in energy projects [24,25]. Citizens act as stakeholders who help write and formulate policy. Due to the broad interpretation of the definition, the concept of co-production is also applied and attuned to other stages of the service delivery cycle; for instance, co-planning, co-design, co-prioritization, co-financing, co-managing, co-delivery, and co-assessment [9,26]. It is possible to involve citizens in multiple stages of the policy cycle to co-produce [27].

Case studies on co-production demonstrate the diversity of contexts in which co-production is used. For example, in the domain of community safety, citizens assist the police through neighborhood watch schemes [28]. In the housing sector, co-production initiatives have been observed [29,30]. In healthcare, collaboration between citizens and local government has been seen in the creation of sports programs that aid patient rehabilitation [17,31]. Additionally, in the field of energy transition, communities have been involved in the design of energy projects [24,25].

Earlier discussions and the conceptualization of co-production stressed the long-term relationship and interaction between co-producing citizens and governmental actors [20,32]. Ostrom argues that public services related to sustainability, but also to education and security, are by definition co-produced, and therefore, the long-term perspective should automatically be part of the conceptualization [10,33]. Concepts like ‘institutionalized’ or ‘long-term relationships’ were included in the definition of co-production. However, more recent definitions have omitted the specific period for which this relationship lasts [14,21,26,34].

3. Materials and Methods

The objective of this article is to examine the interrelationship between a number of factors related to co-production and the orientation of co-production. The existing literature on co-production is largely based on case studies that have identified a number of individual factors. The precise relationship between these factors and the overall development process remains unclear. It is evident from the existing literature that these factors exert an influence; however, the extent to which they contribute to the overall development of orientation remains uncertain. For this article, we employed a narrative review design. This approach allows for a comprehensive and critical analysis of the literature on shifts in the orientation of co-production and the factors influencing this [35,36]. The goal of this narrative review is an authoritative argument based on the existing literature [37]. It differs from a systematic review of the structured methods of data search, screening, selection, analysis, and the presentation of findings. Although the concepts of co-production, its orientation, and related factors, along with the orientations of state, market, and civil society, are well established in the literature, they have not been explicitly combined in previous research, making it hard to generalize findings on how these factors impact each other. As such, a systematic literature review would not align with the aim of this study [36]. Additionally, co-production is closely related to many other concepts, and its orientations are not always explicitly mentioned, further justifying our choice of a narrative review. Accordingly, a narrative review is a more suitable methodology for identifying this gap in the existing literature. The argument presented in the narrative review is that there is a relationship between co-production-related factors and the orientation of co-production. This article draws upon a combination of theoretical data, synthesis, and practical examples [38]. The theoretical data presented in this article have been derived from the existing literature, including literature reviews, empirical articles, and conceptual frameworks. The data presented herein offer insights into the factors and orientations involved in the review process. The theoretical data have been derived from peer-reviewed articles. The process of synthesis involves the combination of elements and ideas from related studies to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the concept in question. The context of the individual factors becomes less important as long as we can place it in the bigger picture. Empirical testing in future research should indicate whether the factors can be judged outside the original context. Practical examples are case studies that demonstrate the application of theory or the consequences of theoretical propositions.

For this narrative review, we exclusively utilized academic databases such as Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the Radboud University library to identify the relevant literature. The search was conducted across full-text journal articles and book chapters available in either English or Dutch. We employed keywords including co-production, citizen participation, citizen initiatives, co-delivery, and related synonyms of co-production. Additionally, we accounted for variations in spelling, such as co-production with and without hyphens. For orientation, we used search terms related to the different domains—state, market, and civil society—as well as institutional logic. Via snowball sampling, we collected more articles that were related to the topics. Furthermore, we have engaged with the work of established co-production scholars, including Alford, Bovaird, Steen, Van Eijk, and Verschuere. By combining these different strategies, we have identified a set of studies that are more relevant to our research question than those based solely on terminology. The review period extended from January 2023 through to August 2024.

Co-production is a term used in various contexts beyond the public sector, including knowledge co-production and applications in the private sector [10]. However, we have only included articles where the concept of co-production is specifically applied within the public sector. The research began with an examination of literature reviews and research agendas to identify and create an overview of the most relevant factors associated with co-production. Following an examination of case studies, a detailed analysis was conducted of the results sections in order to gain insight into the relationship between the relevant factors of co-production and its orientation. Despite the differing focal points of the case studies, trends emerged that suggested a relationship between the associated factors and the orientation of co-production. By drawing on the diverse literature, an analysis was conducted of the interrelationship between the factors relating to co-production and their influence on orientation. At first, this resulted in 16 expectations on how factors related to co-production affect orientation. These 16 expectations were divided into three main categories: motives, abilities and support, and organizational setting.

However, after reading articles gathered in the first round and formulating expectations, we argued that there was some overlap between the expectations. This would make it more difficult to carry out empirical tests for future research. Therefore, we searched for literature again based on interesting links we found in the first collection. The databases remained unchanged; however, the term ‘co-production’ and related terms were combined with more specific factors identified in the initial round; for example, motivation or social capital. The operator OR was employed to combine different synonyms and spellings of the term ‘co-production’, while the operator AND was used to combine these with the various factors related to co-production. A total of 76 articles were included in this narrative review.

This second round of literature gathering had an iterative character, aimed at deepening the understanding of factors and arguments identified during the first sampling round. The search was conducted with a broader scope, encompassing not only the co-production literature but also the literature from related fields, including voluntarism and collaborative governance. We looked at specific factors and found common ground on which we could merge some expectations. This resulted in the four main factors that are presented in the next paragraph: motives, use of resources, social capital, and a supportive culture. In particular, the number of subcategories within the motive category has been consolidated to facilitate a more effective observation of the diverse motives in empirical studies. Additionally, social capital, initially included as a component of abilities in the initial round, has been segregated to allow for a more nuanced examination. In the subsequent, more comprehensive round, we established a link between resources and a supportive culture through the mediating role of social capital, as explained below.

4. Results

4.1. Co-Production Orientations: A Combination of State, Community, and Market Domains

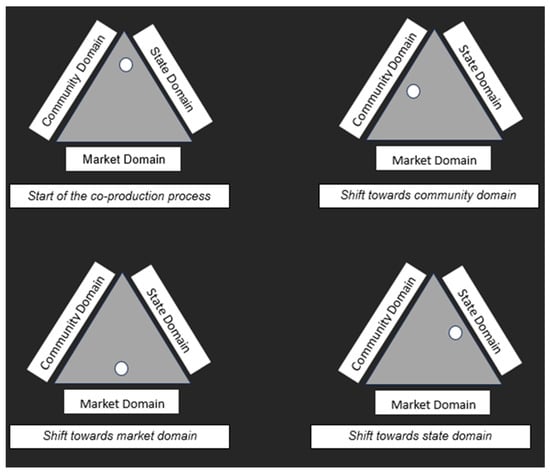

To describe the changes in orientations possibly taking place over time, we draw on three ideal types that span the boundaries and space on which co-production processes take place: the state, the market, and civil society [39]. We argue that co-production is affected by different factors that steer it toward different ideal-typical outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 1. We first explain what these ideal-typical types are, before explaining the relationship between the relevant factors and the ideal-typical types.

Figure 1.

Visualization of the development of co-production.

Firstly, in the domain of the state, hierarchy and formal rules are utilized to guide collaborative efforts [39]. The government assumes a central role, relying on inputs from both the market and citizens to achieve shared public goals. The behavior of the governmental actor may be characterized as steering and, at times, coercive as it seeks to strike a balance between top-down and bottom-up approaches [5]. In practice, co-production bending toward the state domain is often tasked with the implementation of one or more (semi-)public policies, functioning similarly to a public body. In the context of the climate transition, this might involve a public organization responsible for the sustainable energy production of households. The government has a significant influence over day-to-day activities, but the execution of public tasks might be co-produced with citizens.

Secondly, the market domain includes citizens who desire personal interest to co-produce or a local government that is driven by economic incentives [40]. Behavior in the market domain is considered predictable due to actors’ rationality and the pursuit of self-interest, leading to increased efficiency [41]. In the context of the climate transition, this might involve citizens starting an energy cooperative in collaboration with a local government to produce and manage sustainable energy. Later, the cooperation is taken over by or transformed into a private corporation with a profit motive.

Lastly, the domain of the community or civil society represents a smaller group of individuals who share personal and enduring relationships [39]. These communities often emerge in situations where the government is unable or unwilling to provide necessary public services. While these communities may be willing to collaborate with governmental actors, their collaboration is often less structured and formal compared to traditional official partnerships [5]. In the context of the climate transition, this might involve a group of citizens who voluntarily advise their neighbors on how to save energy in their homes. The group operates voluntarily and leverages its knowledge capital.

Overall, these domains differ from each other in three aspects: the utilization of rules, the interaction among various co-producing actors, and the goals targeted by the co-production. The differences between the domains are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the ideal-typical domains of co-production.

In the state domain, rules serve to formalize established structures and hierarchies, delineating the authorities of the involved actors [41]. Deviations from these rules prompt notifications, with consequences for non-compliance, whether informal or formal, being discretionary. In the civil society domain, rules are presented as flexible, contingent upon informal consensus among the actors involved, although they may be formalized when necessary [42]. Here, both formal and informal rules have equal importance. In the market domain, rules are designed to epitomize the most efficient operational processes, serving as a means rather than an end and kept to a minimum [43]. They are formalized, like in the state domain. However, rules serve a different purpose; rules reflect the perceived efficacy and efficiency of the working process. Overall, the use of rules can be classified as either formal or informal, with the state domain at one end and the civil society domain at the other end. The market domain cannot be fully classified according to either the formal or informal use of rules but shows a mix of both.

Interaction in the state domain is characterized by the predominant role of local government in co-production relative to other involved actors. Acting as the chair in meetings, local government sets the tone for acceptable behavior, and others adjust their actions accordingly [41]. Local government assumes responsibility for outcomes and holds hierarchical authority, making independent decisions perceived by others [44]. Possessing the majority of valuable resources, local government wields considerable influence. Conversely, interactions in the market domain prioritize efficiency. Efficiency, of both costs and time, is paramount. Key performance indicators are established beforehand to evaluate outcomes in subsequent phases. Resource utilization must be justified by the projected minimal effort required to achieve the specified indicators. In the civil society domain, meetings are characterized by flexibility, addressing current priorities. Attendees may vary depending on the topic under discussion, with new partners easily integrated into the co-production process. Van den Donk [40] calls this mechanism of interaction ‘love’ or ‘reciprocity’. If people feel connected, they are more willing to interact, and when this connection is missing, the interaction will be less intense.

In the state domain, the primary goal of co-production is to serve society [39,40]. While other objectives may intertwine with this goal, the overarching aim is societal service. In the market domain, the objective is to enhance the efficiency of public service delivery [43]. Conversely, the civil society domain lacks a distinct overarching goal like the other two domains, but caretaking catches it the best [40]. At its core, co-production within the civil society domain focuses on addressing the concerns and aspirations of the co-producing actors.

4.2. Shaping Orientation by Co-Production-Related Factors

Our narrative review of the literature reveals that a broad range of factors are discussed in the literature that play a role in the initiation of co-production. Several of these factors also affect the orientation of co-production or the underlying aspects; this influence is not discussed in a very systematic manner.

Below we will therefore link several factors in a more explicit way to the orientation of co-production. To do so, we turn to the three dimensions underlying the three ideal-type orientations: the utilization of rules, interaction, and goals. The connections we make between the factors and the dimension are sometimes grounded in the existing literature; in other instances, the link is established through logical reasoning and must be understood as loose expectations.

The relationships between these factors and the dimensions behind the ideal type are discussed below and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of the factors of co-production related to aspects of orientation.

First, we elaborate on the motives for participating in co-production. Then, we explain the resources related to enabling co-production, followed by an analysis of social capital that can help to overcome the shortcomings in the available resources. Lastly, we discuss the supportive culture that is beneficial for co-production. All the relationships between the factors related to co-production and the aspects of the ideal-typical outcomes are presented in Table 2.

4.2.1. Motives for Co-Production Affecting Orientation

To initiate a co-production process, it is essential to establish compelling motives for actors to invest their time, resources, and effort into the process. This is the case for citizens and for local governments/civil servants.

4.2.2. Legitimacies of Local Government Affecting Orientation

Local governments can have different motives to co-produce. Mostly, these are related to ‘legitimacy’ concerns, indicating that the actions of governmental actors are grounded on a base of justice. A prominent concern is output legitimacy, which is established through the greater effectiveness or efficiency of policies [45]. Involving or excluding service users in the production process can lead to more tailored services and, therefore, greater efficiency and effectiveness. The decline of the welfare state has led to a depletion of in-house knowledge within local governments, thereby increasing their reliance on external actors and resources [46].

Co-producing with citizens is often not merely an option for local governments but necessary to facilitate effective co-production [47].

We argue that co-production tends to move more toward the market domain when output or outcome legitimacy is dominant. As a result of the focus on efficiency, the relationship between local governments and co-producing citizens should be more formal. This also has consequences for the rules, which become more formal. For instance, rules about collaboration are formalized in a covenant.

We also argue that interaction becomes more efficient. We argue that economic incentives for co-production emphasize that meetings and interactions should have a purpose, leading to interactions based on efficiency. Additionally, the complexity of public service delivery necessitates collaboration; doing it solely through governmental efforts is impractical and cost-prohibitive. This aligns with efficiency-based interaction, as failing to collaborate with co-producing citizens would result in excessive public service costs.

The overall goal of co-production when output legitimacy is dominant is twofold. On the one hand, output legitimacy emphasizes cost reduction as a key goal for co-production, aligning with the business approach to justify local government’s participation. On the other hand, interdependency suggests that without collaboration with co-producing citizens, some public services might no longer be delivered. Therefore, we argue that the goal of co-producing according to output or outcome legitimacy is also tied to serving society. Local governments become more selective in choosing which co-production to participate in, but to prevent the erosion of necessary public services, they may still engage in co-production efforts.

Due to the interplay between cost reduction and the goal of serving society, co-production retains some characteristics of the state domain. However, overall, the market domain would prevail in the dynamics of co-production when output or outcome legitimacy is dominant.

Another motive besides output/outcome legitimacy is input legitimacy, which is based on the premise that co-production is legitimate when it enhances the relationship between citizens and local government despite the effectiveness or efficiency of the output [48]. Co-production is increasingly seen as a fundamental principle, driven by the belief that collective action involving all relevant actors can lead to greater achievements and outcomes [15]. In this respect, it is argued that co-production has become the new norm [47].

Overall, we can argue that orientation tends to lean toward the civil society domain, characterized by the use of informal rules, interaction focused on love, and the caretaking objectives of co-production when input legitimacy is dominant. We argue that the relationship between local government and co-producing citizens should be more horizontal [47]. The rules are likely to be more informal, fostering a thriving horizontal relationship.

This also implies that interactions are based on reciprocity. Hierarchical interaction contradicts the aim of input legitimacy.

The overall goal of co-production, according to input legitimacy, is to manage complex situations with collective action. This goal is tied to serving society and finding the best solutions to societal issues. Consistent with a horizontal relationship, we argue that when input legitimacy is dominant, the primary aim of co-production is to address citizens’ concerns and needs. Therefore, when input legitimacy is dominant, the overall goal of co-production is characterized by caretaking and serving society.

Due to the interplay between the overall goals, it is challenging to formulate precise expectations about the impact of input legitimacy on the orientation of co-production. The diffuse nature of goals means that orientation may also be influenced, to a lesser extent, by aspects of the state domain.

4.2.3. Motivation of Co-Producing Citizens Affecting Orientation

According to Alford [49], citizens are personally motivated to participate in co-production by either extrinsic or intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation involves tangible benefits such as monetary rewards, goods, or services. The underlying assumption is that citizens are willing to engage in co-production if it serves their interests. These incentives are particularly effective for tasks that are reproductive, relatively simple, frequent, and do not require excessive time or effort to accomplish. The task is considered complete if the co-producing citizen meets the specified conditions. It is important to note that making more effort to fulfill the task beyond the specified conditions is not necessary.

In general, when extrinsic motivation is the dominant factor in co-production, it can be argued that co-production is more aligned with the market domain due to the nature of the interaction and the overall objective achieved through co-production. It is difficult to argue that the use of formal rules is caused by extrinsic motivation. We argue that when citizens are motivated by extrinsic motivation, they pursue formal rules more.

When extrinsic motivation is dominant in co-production, the interaction will be characterized by efficiency. Interaction pursues the preset conditions to obtain the rewards that citizens gain from co-producing.

The goal of co-production, when extrinsic motivation is dominant, will be related to cost reduction. In contrast to the governmental perspective on cost reduction, for co-producing citizens, cost reduction is based on the consideration of whether the rewards for co-producing are beneficial compared to the effort it takes to co-produce.

Intrinsic motivation, contrary to extrinsic motivation, stemming from an individual’s interest or enjoyment, represents a source of motivation that cannot be triggered by external influences [49]. Citizens exhibit a willingness to engage in co-production due to several intrinsic motivations identified in the literature [9,17]. These motivations include a desire to belong to a certain group (solidary incentive), a drive to contribute to a meaningful cause (expressive incentive), and the perception that co-production is a social norm (normative purpose) [50]. Intrinsic motivation is recognized as a more sustainable source of motivation than extrinsic incentives.

Related to intrinsic motivation is public service motivation [51,52]. Public service motivation prescribes that motivation is triggered by doing something for the greater good and society in general. Although research on public service motivation initially focused on civil servants, there is a growing recognition in current research of its applicability to citizens [53].

Overall, when intrinsic motivation is dominant in co-production, we can argue that co-production moves toward the civil society domain because of the nature of the interaction and the overarching goals of co-production. Intrinsic motivation is enhanced by the use of informal rules, which accommodate the variation in co-producing citizens’ passions and drive. However, we cannot argue that intrinsic motivation enhances the use of informal rules. We can only say that intrinsic motivation flourishes with the use of informal rules and is diminished by the use of formal rules.

Despite differences in motivation, citizens can unite in groups with shared goals. It is argued that because intrinsic motivation is individually operationalized, co-production interactions tend to be based on reciprocity when co-producing citizens address their priorities. Within the interaction, there is some form of solidarity that everyone is co-producing for the greater good.

To form a group, co-producing citizens find a way to address all interests in one form. Therefore, when intrinsic motivation is present, the overall goal is assumed to be caretaking, which is more flexible in addressing what is seen as important at that moment. However, these co-producing citizen concerns are also related to serving society. Co-producing citizens observe a lack of governmental participation in some public services and try to fill those voids. Therefore, the overall goal of co-production can also be related to serving society, creating a mixture of the civil society domain and the state domain.

4.3. Use of Supportive Material and Financial Resources Affecting Orientation

Secondly, when there is drive, this does not guarantee that co-production gets off the ground. Resources and abilities are necessary to make local governments and co-producing citizens able to co-produce. Resources can be divided into various aspects, like human capital, material and financial support, knowledge, and workspace. As mentioned, citizens often bring in resources.

Local governments can also bring in resources. This support can take the form of financial aid, material resources, administrative assistance, or specialized training sessions aimed at bridging the knowledge gap between civil servants and citizen co-producers [54,55].

Such support, moreover, serves to establish co-producing citizens as genuine partners of the local government, thereby providing a motivation to co-produce. By receiving governmental support, co-production obtains some form of legitimacy and appreciation for the co-producing citizens as the preferred collaboration partner of the local government [56]. As co-producing citizens need to judge whether they are good enough to co-produce, this can affect their perception of self-efficacy to co-produce or not [57].

The use of resources has an impact on orientation. In contrast to the motives for co-production, the relationship between the use of resources and the utilization of rules remains undetermined. When the use of resources is dominant in co-production, we expect that co-production moves toward either the state domain or the civil society domain. This expectation arises from the diffused argumentation regarding the effect of resource use on the interaction and the overall goal of co-production.

The inverse relationship between the utilization of rules and the use of resources can be more clearly delineated. The negative impact of bureaucracy on social capital and input legitimacy, in turn, indirectly affects the utilization of resources. Nevertheless, this does not elucidate how the utilization of resources affects orientation.

The use of resources affects the interaction in co-production in two distinct ways. Firstly, the use of resources creates more possibilities for interaction, which in turn leads to the formation of some form of solidarity. The use of resources engenders a more benevolent and reciprocity-based interaction. Secondly, the use of resources also entails agreements regarding influence and how the resources may be allocated. Consequently, we posit that in addition to interaction based on love, we may also assume that the interaction becomes more hierarchical.

The overall goal of co-production based on the use of resources aligns with the interaction. On the one hand, we expect the goal to be addressing immediate issues of importance. The use of resources for immediate solutions demonstrates co-production involvement and a willingness to promptly address concerns. On the other hand, when resources are used in a long-term and structural manner, we can argue that the goal of using resources is to serve society. In this way, resources are allocated to issues that affect society as a whole.

4.4. Social Capital Affecting Orientation

Thirdly, when resources are not available, social capital might offer a solution for this shortcoming. Putman [58] describes social capital as the possibility of obtaining benefits from a connection. The type of resource offered depends on the nature of the link. In his later work, he makes a distinction between bridging social capital and bonding social capital [59].

Bridging social capital is characterized by weak relationships that serve as bridges between organizations within a network [59]. The primary purpose of these links is to form coalitions and establish external relationships, utilizing weak ties to disseminate information across the network. Conversely, bonding social capital is more intensive and focuses on offering emotional support and fostering loyalty within the group or network. Bonding social capital represents strong ties between actors or organizations.

Social capital can facilitate efficient interactions by reducing the obstacles to reaching the right person [60]. Social capital is inherently connected to the concept of trust, though the relationship between them is complex. There is debate over whether a low level of trust negatively or positively affects the willingness to interact [61]. On the one hand, low levels of trust may drive individuals to interact more to exert control over the actions of others. On the other hand, high levels of trust can lower barriers to interaction, facilitating easier engagement. Regardless of the initial level of trust, the outcome of successful interactions typically leads to an increase in trust among the actors involved, thereby positively affecting subsequent interactions.

The individual who makes the connection and is responsible for the social capital in the co-production process is the boundary spanner [62]. The boundary spanner acts as a mediator, simultaneously representing the local government or co-producing citizen while establishing connections among various actors involved in co-production [63]. They promote an array of broader outcomes, which are not (only) preset by public authorities [15]. To fulfill this role effectively, boundary spanners employ enabling skills to foster horizontal relationships and interpersonal skills such as active listening, empathy, effective communication, and open-mindedness [64]. Moreover, the number of links can be influenced by the available resources. There is a feedback loop within these concepts: when the co-production has access to a physical work environment, it becomes easier to meet and interact with people, thereby strengthening the ties between co-producing actors [65].

Based on the utilization of rules, interaction, and the overall goal of co-production, we expect that co-production moves toward a combination of the civil society domain and the state domain when social capital becomes dominant. We cannot determine the exact balance in which these domains might prevail.

We argue that rules are mostly informal. Rules are formed based on interaction and mutual consent and do not require formalization. Rules are flexible and can be adjusted when one of the actors initiates it with the consent of the other.

Social capital affects the interaction between co-producing citizens and the local government. On the one hand, interaction can become more efficient because social capital limits official barriers and procedures, thereby creating more possibilities to interact. On the other hand, interaction is based on reciprocity. Actors become more involved with each other the more social capital prevails. They know what concerns actors, and interaction creates more solidarity.

In line with interaction, the overall goal of co-production can be argued to be related to taking care of or serving society. Due to the reciprocal interaction and the mutual interest created through this dynamic, the overall goal often reflects a combination of the desires of the local government and those of the co-producing citizens. As they interact more frequently, the overall goal of co-production tends to align closely with the individual interests of the actors involved.

4.5. Supportive Culture Affecting Orientation

In addition to the motives for co-producing, the available resources, and social capital, a supportive culture plays a crucial role in determining the feasibility of such collaborative efforts. How citizens and local government entities organize themselves and in what institutional context they operate can either facilitate or impede the co-production process. This encompasses aspects such as openness toward co-production, political stability, and the level of bureaucracy.

Firstly, openness among civil servants and political actors plays a significant role. This aspect is particularly necessary during the initial phase of co-production [6]. An open culture can be understood from various perspectives, with one perspective defining it as an organization that is willing to share risks [66]. This entails the sharing of autonomy with citizens, which naturally leads to shared responsibilities [26]. When there is an open culture toward co-production, interactions among co-producing actors become easier.

Alongside an open culture, bureaucracy plays a mitigating role. Local governments typically operate through a rule-based and norm-driven approach, whereas co-production necessitates greater flexibility [23]. This creates a dilemma for local governments as they strive to standardize processes and adhere to regulations while also being expected to provide space within the boundaries of legislation [13]. Standardization is recognized as a barrier for boundary spanners to effectively carry out their work and realize an equal relationship between co-producing citizens and the local government [62]. Bureaucracy thus affects the input legitimacy of local government. Moreover, co-producing citizens often feel constrained by bureaucracy, as it coercively limits their space for action and hinders a proactive approach to engaging with new people [67]. Bureaucracy negatively affects the intrinsic motivation of co-producing citizens too [53].

Lastly, the stability of local politics can be classified as an aspect of the supportive culture in which co-production thrives. Co-production must be tolerated by public administrators or the city council, especially for co-production at a local level [54]. The relationship with political actors is essential for the allocation of governmental resources. Frequent changes in political actors necessitate rebuilding these connections, which can negatively impact co-production due to the instability of resource allocation.

When a supportive culture—open and politically stable without unnecessary bureaucracy—is dominant and present in co-production, we argue that co-production moves toward the civil society domain. Rules are most often informal. To create an open culture, formal rules are limited to a bare minimum to create space and offer customization.

The interaction between local government and co-producing citizens becomes characterized by reciprocity. A supportive culture enhances social capital among the actors, which results in solidarity for each other.

The overall goal co-production aims for is partly caretaking. This aligns with the utilization of rules and interaction. A supportive culture open to co-production can address citizens’ issues that require immediate action. On the other hand, a supportive culture also relates to serving society when there is a belief that such a culture improves public services.

4.6. Dynamics Within the Orientation of Co-Production

The factors discussed above are not static, meaning that shifts in these factors can lead to changes in the overall orientation. Although some examples of such changes can be found in the literature, their direct impact on the co-production orientation is not always visible or discussed in the literature.

In part, this seems to result from the fact that the factors are not only connected to orientation but also to each other. As a result, a change in a factor may impact orientation in an indirect way, via a different factor or set of factors. In some cases, these changing factors reinforce one another, pushing co-production toward a consistent orientation. However, in other cases, they can pull orientation in conflicting directions. We return to this in the discussion below.

In this section, we will explore some of these dynamics and show how they may influence orientation in ways that differ from our initial expectations. We do not aim to provide a full theorization of these dynamics. This would lead to a further complication of our conceptual model. However, in applying our conceptual model and exploring our expectations in future empirical research, it is important to be aware of these dynamics as a first step. One example is Van Eijk’s [28] research on neighborhood watch schemes. This study reveals a shift in motivation among co-producing citizens. Initially, the co-producing citizens were motivated to undergo specific training and participate in co-production. However, over time, and particularly during colder winter months, their motivation to assist the local police gradually waned. Moreover, citizens began to question the impact they could make and felt a lack of appreciation from local officials. The consequence was that citizens dropped out of the co-production.

Tonũrist and Surva [68] observed a similar pattern in their research on various co-production cases related to safety. Co-producing citizens who served as voluntary firefighters initially displayed high levels of motivation. However, similar to Van Eijk’s findings [28], this motivation decreased over time due to a desire for greater responsibility that could not be fulfilled given the nature of their tasks.

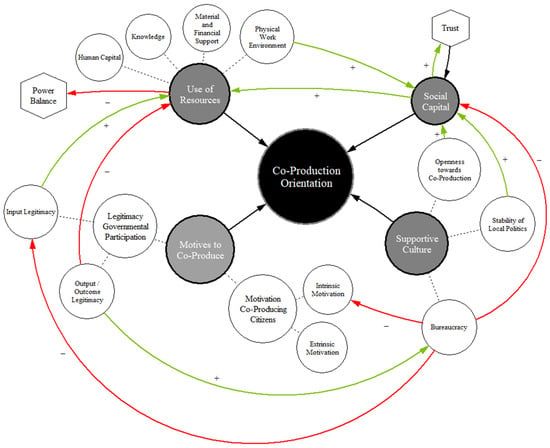

The two examples illustrate how factors related to co-production intertwine; for instance, a supportive culture influences the motivation of co-producing citizens. Individually, each factor would have guided co-production in different directions, but due to their interplay, the literature suggests that a supportive culture tends to be more dominant than citizens’ motivation. This is not the only connection between these factors. This is further clarified in Figure 2, which shows how some factors support each other due to positive relationships, resulting in the orientation of co-production being influenced in a comparable manner. For example, there is a positive relationship between input legitimacy and the use of resources. Conversely, some factors negatively relate to each other, creating dynamics that have opposing effects on the orientation of co-production.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of co-production orientation.

For example, the relationship between supportive culture and social capital can steer orientation in two ways. Social capital can be either positively or negatively affected by factors such as the level of bureaucracy, openness toward co-production, and the stability of local politics. In this case, it is not clear which of these factors has the most influence on the outcome, even though they might steer orientation in different directions. When a high level of bureaucracy negatively impacts social capital, we observe a clash between a factor that steers orientation more toward the state domain and a factor that steers orientation more toward the civil society domain.

The relationship between supportive culture and social capital also influences the use of resources. If supportive culture positively affects social capital, then social capital will, in turn, positively impact the use of resources more than if it were negatively affected. Additionally, the use of resources is influenced by the legitimacy of the local government to participate in co-production, which can have contrasting effects, leading to either a strict or generous use of resources.

The latter shows that, besides focusing on the tensions and dynamics between factors related to co-production, we should also be aware of the tensions within factors. Motives for co-production, for example, illustrate how factors themselves might steer the orientation of co-production in different directions. When citizens and local government share aligned motives—such as input legitimacy and intrinsic motivation or output/outcome legitimacy and extrinsic motivation—the factor of motive provides a clear direction. However, the situation becomes more complex and intriguing when the motives of the co-producing citizens and local government are not aligned. In such cases, understanding how orientation is decided and steered becomes crucial.

5. Discussion

The current co-production literature predominantly highlights cases in which co-production processes have developed into stable and more institutionalized forms, which may suggest that all co-production can be expected to develop toward a sustainable format [64]. In practice, much co-production fails to reach the stage of being fully established and stable. Even when co-production does get off the ground, there remains a possibility that it ceases to operate for various reasons, such as the withdrawal of citizens who want to participate or the termination of governmental support [28,69].

The focus on case studies often limits the development of a comprehensive theory in the context of co-production, as it tends to emphasize specific incidents and events that may not fit within the broader structure of co-production [4]. By shifting the focus to the orientation of co-production, we aim to enrich the literature and connect existing pieces that have yet to be fully integrated, as presented in our conceptual model. The literature argues that the field needs to move beyond situational research and focus more on the processes of change and development [70]. These aspects were integral to the original conceptualization of co-production [20,32] but have been somewhat neglected in subsequent studies [14,21,26,34]. In order to move away from the initial orientation of co-production, between the state and the civil society domains, co-production must proceed with some organizational development to move from an idea to an established organization. If co-production has processed this, then it can (re-)orientate itself at the level of state, market, and civil society [71]. To a certain degree, the level of stability might depend on the orientation of co-production. When co-production leans more toward the state domain and the local government decides to cut the budget, this decision impacts both the orientation of co-production and its level of stability.

We can say that the use of informal rules and interactions based on reciprocity are most profound in the theoretical expectations. This presumes that co-production moves more toward the civil society domain. If we take a closer look at the goal of co-production, we can argue that serving society and caretaking are equal in some way. This means that when the goal of co-production is more dominant compared to the utilization of rules and interaction in the orientation of co-production, co-production moves toward the state domain and the civil society domain. Compared to the origin of co-production, as visualized in Figure 1, this makes no significant difference because co-production is already positioned between those two domains in the initial phase. However, when output/outcome legitimacy or extrinsic motivation becomes more dominant over time in co-production, we presume that co-production moves more toward the market domain.

These outcomes are presented in Table 2. It shows that orientation depends partly on which factor—motive, resources, social capital, or a supportive culture—has the biggest influence on orientation but also on which aspect of orientation—the utilization of rules, interaction, or goal—determines that outcome the best.

One explanation for the diffuse outcome of some factors is that co-production, regardless of the definition used, is always related to public service delivery. The fact that most factors score on aspects of the state domain is therefore not related to the specific factor but to the core of co-production. Co-production always has a link to public service, which is best represented in the state domain. However, the literature also shows that public–private collaboration can effectively fulfil public services [72]. Even though the state domain opts for a collaborative effort, it still views a central position for the governmental actor, which might create tension with the market domain that pursues a different dynamic of hierarchy [39]. The fact that this aspect is not as extensively included in the aspects of the state domain might explain the observed outcomes. Additionally, it might become difficult to make a clear distinction between the state and other factors. McMullin [73] argues that a state strategy that aims to increase community goods inherently blurs the boundaries of the state and civil society. The same argument can be made for a state that aims for public–private collaborations, blurring the boundaries of the state and market domains.

Another explanation for the diffuse outcome of some factors is that the ideal types of state, market, and civil society are not exhaustive when it comes to the development of co-production orientation. As argued above, the distinction between the state and civil society domains can be blurry. Differences will be bridged, making them operate identically.

This aligns with a significant debate regarding the use of multiple institutional logics, which are often intertwined with the conceptualization of domains [74]. Institutional logics guide the behavior of organizations and institutions, much like how the domains themselves are assumed to operate [75]. To some theoretical extent, multiple aspects of the domains can coexist [41]. However, it becomes interesting to explore how these different aspects interact. Do they blend into a new domain? Do they collaborate, maintaining their individual characteristics? Or is it impossible for multiple aspects of different domains to coexist over the long term, eventually blocking each other and making it difficult for co-production to move away from its initial position? These questions are particularly relevant for empirical research on the development of the orientation of co-production as well as co-production in general. Some might argue that the aspects of domains are contested, which may lead to co-destruction instead of co-production in the long term [76]. It is crucial to explore whether these domains interact cooperatively or destructively when influencing co-production orientation.

We argue that it is time to move beyond merely identifying that co-production may have competing orientations. The next step should involve conducting explanatory research to understand the underlying causes of these competing orientations and developing strategies for effectively managing them. The development of orientation becomes especially relevant in the context of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 at the latest. Governmental actors emphasize the significant role that citizens can play in addressing societal issues. However, this emphasis brings with it a shared responsibility that must be sustainable over a longer period. By focusing on the development of orientation, we can gain insights into the expectations placed on each party within the co-production process. If there is a mismatch in these expectations, it can impact other factors related to co-production as well, as described in the previous paragraph. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for ensuring effective and long-lasting collaborations between citizens and governmental actors in the pursuit of climate neutrality.

Understanding the development of the orientation of co-production enables us to establish why and how co-production shifts from its initial position. This draws attention to the potential loss of democratic engagement [7,77]. When we encourage citizens to participate, in achieving climate goals, for instance, which are inherently public objectives, we might assume an inherent connection to the state domain. However, our theoretical research suggests that co-production can develop independently of local government influence, or at least, there are factors within co-production that promote such an orientation.

This raises critical questions about the true intentions behind promoting citizen participation. Is it a genuine effort to involve citizens in public decision-making, or is it a strategy to offload governmental responsibilities onto citizens? Moreover, are we overlooking the potential loss of democratic engagement by not critically evaluating the effectiveness of citizen participation? Co-production is often portrayed as a silver bullet, but in some cases, it falls short of delivering the expected outcomes [8,78]. The co-production literature is mostly built on successful case studies; limited failed cases are represented [4]. As McMullin highlights, co-production is not always the best solution, particularly when time and resources are limited, when it replaces paid work, or when it demands too much effort from citizens to effectively participate [8]. The literature on co-production is increasingly moving toward a debate in which the negative effects are given equal consideration alongside the positive aspects [7,34,79]. This shift contrasts with earlier research, which predominantly focused on the benefits of co-production. To do this correctly, we must not only focus on the short-term effects but also consider long-term development to comprehensively evaluate the concept of co-production. We argue that the orientation of co-production should be considered as a key aspect in evaluating the concept. Additionally, it is important to assess how local governments adapt their policies to support the evolving nature of co-production over time. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for ensuring that citizen participation in climate goals—and citizen participation in general—is both meaningful and effective.

Qualitative longitudinal research is needed to validate or refute theoretical predictions, particularly in examining the changes and dynamic relationships among the four main factors: motives, use of resources, social capital, and a supportive culture [80]. In practice, all orientations are possible, as illustrated when the domains were explained. However, we do not know which factors influence orientation the most. To continue with the example of budget cuts, if that happens, then the co-production should re-orient itself and obtain finances from other public bodies or move more toward private or community solutions. A co-production, for example, can make a profit to overcome financial shortages, which is more related to the market domain, or rely on crowdfunding, which is related to the civil society domain.

This research should also consider whether a new orientation still qualifies as co-production. Traditionally, co-production involves collaboration between citizens and local government, but the ‘co-’ in co-production may take on new meanings [11]. In extreme cases, it could evolve into ‘competitive’ production, shifting entirely to the market domain, or the ‘co-’ could diminish, resulting in public service delivery solely managed by the local government. The outcome of this discussion can introduce a new dimension to the conceptualization of co-production or restore elements of the concept that have been overlooked over time. For example, earlier definitions and conceptualizations explicitly highlighted the long-term aspect of co-production [20,32]. By focusing on change and development, we can further explore and deepen this often-omitted part of the conceptualization. One possibility is that co-production is always temporary and eventually becomes integrated into one of the three domains. Furthermore, future studies should explore how these factors influence the orientation of co-production and its effects on public service delivery. The goal of co-production research is to develop a more integrated theory [81].

Empirical research that considers various factors can establish a new theory on the development of co-production orientation. This research must adopt a longitudinal perspective. While retrospective research can identify some elements of a new theory on the orientation of co-production, it has pitfalls. Retrospective research may incorrectly attribute importance or logic to events after they have occurred. In contrast, longitudinal research, which follows developments in real-time, can provide a more accurate understanding of the events and their true impact on the orientation of co-production. A combination of both methods is favored to create better insights into the dynamics of the orientation of co-production.

6. Conclusions

To address the research question—What is currently understood in the co-production literature regarding the shifts in co-production orientation, and how can we comprehensively analyze these developments?—this article proposes a conceptual model that explains the factors contributing to this shift, which will be empirically tested in future research. To do so, the ideal-typical orientations have been distinguished from each other in three aspects: the utilization of rules, interaction, and the overall goal of co-production. Next, we have identified the relevant factors in the co-production process that affect the overall orientation, classifying them into four main categories: motives to co-produce, the use of resources, social capital, and a supportive culture. These aspects have been related to the aspects of orientation and how they influence the placement of co-production at the level of state, market, and civil society.

In this narrative review, we argue that these factors shape the development of co-production and can shift its positioning between the orientation of state, community, and market. Most factors tend to steer the orientation of co-production more toward civil society, but this is not a definitive prediction. The overall orientation of co-production depends on how the various factors interplay with each other and which aspects of orientation are most influential in determining its direction. To better understand these dynamics, qualitative longitudinal research should be conducted to trace the interactions between and within the factors that influence co-production orientation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ozaki, Y.; Shaw, R. Citizens’ Social Participation to Implement Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, J.; Ansell, C.; Sørensen, E. Metagoverning the Co-Creation of Green Transitions: A Socio-Political Contingency Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, B.; Brandsen, T.; Pestoff, V. Co-production: The State of the Art in Research and the Future Agenda. Voluntas 2012, 23, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Trommel, W.; Verschuere, B. The state and the reconstruction of civil society. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, J.; Honingh, M.; Brandsen, T. User co-production of public service delivery: Exploring mechanisms and conditions for building trust. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2015, 28, 550–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, T.; Brandsen, T.; Verschuere, B. The Dark Side of Co-Creation and Co-Production. In Co-Production and Co-Creation. Engaging Citizens in Public Services; Brandsen, T., Steen, T., Verschuere, B., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, C. The case against co-production as a silver bullet: Why and when citizens should not be involved in public service delivery. Public Manag. Gov. Rev. 2024, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nabatchi, T.; Sancino, A. Varieties of Participation in Public Service: The Who, When, and What of Coproduction. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.A.; Wyborn, C. Co-production in global sustainability: Histories and theories. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 113, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Honingh, M. Definitions of Co-Production and Co-Creation. In Co-Production and Co-Creation; Brandsen, T., Steen, T., Verschuere, B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pestoff, V. Collective Action and the Sustainability of Co-Production. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, C.; Cuppen, E. Coproduceren in een complex belangenspeelveld: Dilemma’s voor de gemeentelijke overheidsprofessional. Bestuurskunde 2022, 31, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, S.; Steen, T. Realizing public values in the co-production of public services: The effect of efficacy and trust on coping with public values conflicts. Int. Public Manag. J. 2022, 25, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Bryson, J.; Crosby, B. How public leaders can promote public value through co-creation. Policy Politics 2021, 49, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewello, H. Towards a Theory of Local Energy Transition. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, C.; Steen, T. Why people co-produce: Analyzing citizens’ perceptions on co-planning engagement in health care services. Public Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, J.L. The Multiple Facets of Co-Production: Building on the work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, D.; Van Eijk, C. In or Out: Developing a Categorization of Different Types of Co-Production by Using the Critical Case of Dutch Food Safety Services. Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 1044–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Service. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Honingh, M. Distinguishing Different Types of Coproduction: A Conceptual Analysis Based on the Classical Definitions. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.L.P.; Uittenbroek, C.J.; Hegger, D.L.T.; Driessen, P.P.J. From citizen participation to government participation: An exploration of the roles of local governments in community initiatives for climate change adaptation in the Netherlands. Environ. Policy Gov. 2019, 29, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjørtler Elkjær, L.; Horst, M.; Nyborg, S. Identities, innovation, and governance: A systematic review of co-creation in wind energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solman, H.; Smits, M.; Van Vliet, B.; Bush, S. Co-production in the wind energy sector: A systematic literature review of public engagement beyond invited stakeholder participation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 72, 101876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Loeffler, E. From Engagement to Co-production: The Contribution of Users and Communities to Outcome and Public Value. In New Public Governance, the Third Sector and Co-Production; Pestoff, V., Brandsen, T., Verschuere, B., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 35–60. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, J.; Nitz, S. Learning in Citizen Science: The Effects of Different Participation Opportunities on Students’ Knowledge and Attitudes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, C. Helping Dutch Neighborhood Watch Schemes to Survive the Rainy Season: Studying Mutual Perceptions on Citizens’ and Professionals’ Engagement in the Co-Production of Community Safety. Voluntas 2018, 29, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, S.; Steen, T. The sustainability of outcomes. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2020, 33, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, R.M. Sandwiched between patronage and bureaucracy: The plight of citizen participation in community-based housing organisations in the US. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.G.; Skjerning, H.T.; Burau, V. The why and how of co-production between professionals and volunteers: A qualitative study of community-based healthcare in Denmark. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2022, 43, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Moore, M. Institutionalised co-production: Unorthodox public service delivery in challenging environment. J. Dev. Stud. 2004, 40, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Formulating the elements of institutional analysis. In Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis; Indiana University: Bloomington, MN, USA, 1985; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.T.; Deniss, A.R. An Introduction to Writing Narrative and Systematic Reviews—Tasks, Tips and Traps for Aspiring Authors. Heart Lung Circ. 2018, 27, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaššaj, M.; Peráček, T. Sustainable Connectivity-Integration of Mobile Roaming, WiFi4EU and Smart City Concept in the European Union. Sustainability 2024, 16, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, T.; Van den Donk, W.; Putters, K. Griffins or Chameleons? Hybridity as a Permanent and Inevitable Characteristic of the Third Sector. Intl. J. Public Adm. 2005, 28, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Donk, W. De Gedragen Gemeenschap: Over Katholiek en Maatschappelijk Organiseren de Ontzuiling Voorbij; Sdu Uitgevers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hee Min, B. Hybridization in government-civil society organization relationship: An institutional logic perspective. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2021, 32, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubik, J. How to Study Civil Society: The State of the Art and What to Do Next. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2005, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karré, M.P. Heads and Tails: Both Sides of the Coin; Eleven International Publishing: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, P.H.; Ocasio, W.; Lounsbury, M. The Institutional Logics Perspective: A New Approach to Culture, Structure and Process; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, J.; Painter, G. From Citizen Control to Co-Production. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2019, 85, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriens, E.; Buskens, V.; De Moor, T. Networks and new mutualism: How embeddedness influences commitment and trust in small mutuals. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2021, 19, 1149–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Making Governance Networks Effective and Democratic Through Metagovernance. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V. Conceptualizing Legitimacy: Input, Output, and Throughput. In Europe’s Crisis of Legitimacy: Governing by Rules and Ruling by Number in the Eurozone; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, J.L. Why do public-sector clients coproduce? Toward a contingency theory. Adm. Soc. 2002, 34, 32–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanleene, D.; Verschuere, B.; Voets, J. Co-Producing a Nicer Neighbourhood: Why do People Participate in Local Community Development Projects? Lex Localis 2017, 15, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coursey, D.; Yang, K.; Pandey, S.K. Public Service Motivation (PSM) and Support for Citizen Participation: A Test of Perry and Vandelabeele’s Reformulation of PSM Theory. Public Adm. Rev. 2012, 72, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.E.; Egger-Peitler, I.; Höllerer, M.A.; Hammerschmid, G. Of Bureaucrats and passionate public managers: Institutional logics, executive identities and public service motivation. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 861–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, O.; Schott, C. Behavioral effects of public service motivation among citizens: Testing the case of digital co-production. Int. Public Manag. J. 2023, 26, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, H.; Van Eijk, C. Niet alleen lokaal. Beleidsonderzoek Online 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederhand, J.; Bekkers, V.; Voorberg, W. Self-Organization and the role of Government: How and why does self-organization evolve in the shadow of hierarchy? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, B.; De Corte, J. The Impact of Public Resource Dependence on the Autonomy of NPOs in Their Strategic Decision Making. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2014, 43, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M.K. Citizen Coproduction: The Influence of Self-Efficacy Perception and Knowledge of How to Coproduce. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2015, 47, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]