Cities and Governance for Net-Zero: Assessing Procedures and Tools for Innovative Design of Urban Climate Governance in Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Contribute to understandings of the new experimental city governance theory of change model emerging by isolating and elaborating its core dimensions; and,

- (2)

- Set the stage for empirical work on whether/how concepts of good governance in the abstract (embodied in the tools’ design) are influencing changes to urban governance that can support policies for carbon neutrality.

1.1. Example 1: The Rise of Cities and Non-State Actors in the Global Governance Regime

1.2. Example 2: The Growing Influence of the Mission Approach–Public Sector Reform Can “Save the World”

1.3. Example 3: The Green Growth Narrative—Co-Benefits and Thriving in the Doughnut

1.4. Mobilization, Good Governance Models, and Procedural Governance Tools (PGTs)

2. Methodology

- (1)

- How do orchestrating bodies and transnational municipal networks (TMNs) supporting local actors envision good governance?

- (2)

- What procedural governance tools (PGTs) are local governance actors using?

- (3)

- What are the common theoretical underpinnings of emerging PGTs?

- (1)

- Mapping of framings and frameworks across initiatives targeting cities and local authorities from known initiatives (see Supplementary File S1); descriptive/guidance materials were quickly scanned for governance-related frameworks during searches.

- (2)

- Import into NVivo Release 1.0 (R1) to conduct word frequency scans for key governance, net-zero, tools/mechanisms, and resilience terms based on Step 1 (see Supplementary File S2 for terms used), plus a systematic scan for any tools/relevant concepts missed.

- (3)

- In-depth analysis of the 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities (Cities Mission) and Energy Cities corpus documents to identify key emerging mission-oriented governance concepts with academic literature in parallel and additional tools/concepts discovered in the process of reviewing existing documents (28) and associated materials via the snowballing method.

- (4)

- Finalize corpus with additional tools/conceptual materials from Step 3, repeat Step 2, and develop summaries of the 25 tools from 35 documents: detailing the purpose, climate action focus, design principles and values, and impact logics or assumptions toward a theory of change.

- (5)

- Construction of the evaluative framework—REPAIR: Reflexivity, Enabling/Embedding, Participatory, Integrative, Adaptive, and Radicality. Based on the steps above and the literature associated with the tools, iteratively developed the search terms/codes (see Supplementary File S2) using an inductive approach from observed frequencies and common descriptions/terms across the corpus. For example, during the corpus finalization in Step 4, the additional tools’ materials expanded the subthemes. Evaluation of tools against these dimensions based on their documents in the corpus (visualized in Table 2—see Supplementary File S3 for full list).

- (6)

- Critically reflected on the emerging EU Cities Mission governance innovation approach based on Steps 1–5 and relevant literature, with a focus on broader implications of circulating conceptions of governance versus governance development needs on the ground.

2.1. Selection of PGTs

- (1)

- Publicly available guidance/knowledge resources or synopses of local and/or city-scale net-zero governance approaches, structures, or frameworks; and,

- (2)

- (2) Policy instrument guidelines that specifically outlined governance processes or concepts (e.g., CCC, SECAP, SUMP).

2.2. Analysis of the City Governance Mechanisms/Frameworks

3. Results Toward a Procedural Governance Tool (PGT) Evaluative Framework

3.1. Good Governance Dimension I–Reflexivity

- (1)

- Consideration of and acting upon legitimacy tensions (i.e., political context, democratic structures vs. transformative ambitions/ways of working, and representation of wider interests/preferences beyond “business as usual” actors), including seeing the relationship between local government and citizens with new eyes;

- (2)

- Being mindful of which contextual factors/conditions (based on system analyses) are relevant to the radicality/innovation activities needed and adapting plans during the process; and,

- (3)

3.2. Good Governance Dimension II–Enabling/Embedding

3.3. Good Governance Dimension III–Participatory

3.4. Good Governance Dimension IV–Adaptivity

3.5. Good Governance Dimension V–Integrative

3.6. Good Governance Dimension VI–Radicality

- (1)

- The ways of governing leading to implementable, bankable climate neutrality plans (i.e., stakeholder identification, engagement, communication, and collaboration; information provision/knowledge development; on-the-ground collaboration dynamics; and establishing effective co-creation/production);

- (2)

- The structures of governance, including the allocation of budget and human resources for innovation managers, taskforces, or advisory boards/bodies responsible for consolidating and tracking innovation activities across the local government context (agreements, pilots, partnerships, etc.); and,

- (3)

- The capacities of governance, such as developing appropriate complex change initiative coordination, brokerage, engagement, and innovation systems development skills within local administrations and communities.

4. Discussion—Cities’ Net-Zero Journey and the Use of Procedural “Good Governance” Tools

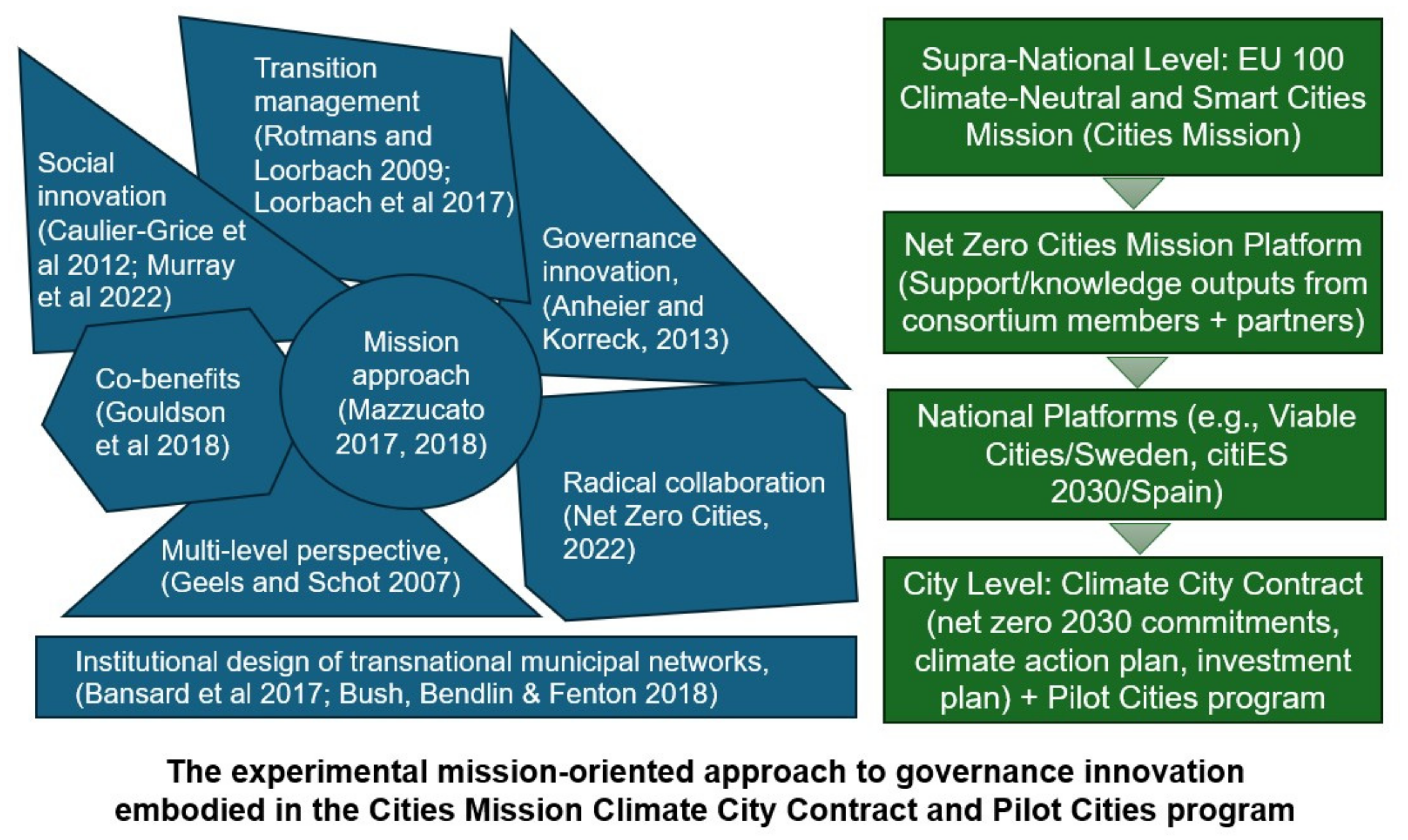

4.1. The Emerging EU Cities Mission Governance Innovation Approach

4.2. Common Governance Innovation Challenges and Emerging Questions

4.3. Limitations

- (1)

- Formal documents can only offer a partial (and idealized) perspective, especially given the often hidden institutional and political dynamics at play across local contexts and settings. As such, there are limits on the extent to which deeper insights can be gleaned solely from a corpus of public documents.

- (2)

- The volume, due to the proliferation of PGTs, creates challenges for capturing and analyzing all existing PGTs comprehensively.

- (3)

- While attention was paid to local perspectives countenanced in the documents on the frameworks and concepts analyzed, the analysis lacks firsthand accounts of challenges, limitations, significance, etc.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Net-zero as a broad appeal organizing construct with market-based and command and control logics and net-zero “badges” or credentialism (shallow, performative governance);

- (2)

- The possibilities of operationalizing deeper, more lasting, and transformative governance that accounts for alternative framings rooted in democratic, justice, and more resilience-oriented norms and visions.

- (1)

- Understanding the role and opportunities/limitations of national policy platforms referred to in the Introduction on the localization of SDGs/carbon neutrality pathways;

- (2)

- Developing monitoring (and learning) systems specific to governance innovation, with a focus on developing/refining governance process indicators (REPAIR could provide a useful starting point for this);

- (3)

- Unpacking and understanding (wider/other sets of) procedural tools and their interactions/influence on governance practice, using REPAIR as an analytical tool alongside more in-depth engagement with key actors; and,

- (4)

- Developing empirical insights and evidence for the most effective tools or set of tools, i.e., are they fit for purposes of aligning with the national level, cohering with existing local processes, engaging/mobilizing citizens and stakeholders, etc.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| Cities Mission | EU Mission for 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities |

| C40 | C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group |

| CCC | Climate City Contract |

| CoM | Covenant of Mayors |

| EC | Energy Cities |

| ECF | Enabling Conditions Framework to Mobilize Urban Climate Finance |

| ECP | European Climate Pact |

| GCC | GreenClimateCities |

| GCoM | Global Covenant of Mayors |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| ICLEI | Local Governments for Sustainability |

| LGD | Local Green Deal |

| Local PACT | Local Participatory Agreement for the Climate Transition |

| MEL | Monitoring, Evaluation, and Learning |

| NDCs | Nationally Determined Contributions |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NZC | NetZeroCities |

| PB | Participatory Budgeting |

| PCP/BARC | Partners for Climate Protection Program and Building Adaptive and Resilient Communities |

| PGTs | Procedural Governance Tools |

| SECAP | Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan |

| SCGP | Climate-Neutral and Smart City Guidance Package |

| SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| SUMP | Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan |

| TOC | Theory of Change |

| TMNs | Transnational Municipal Networks |

| UCLG | United Cities and Local Governments |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| WRI | World Resources Institute |

| WWF | World Wildlife Fund |

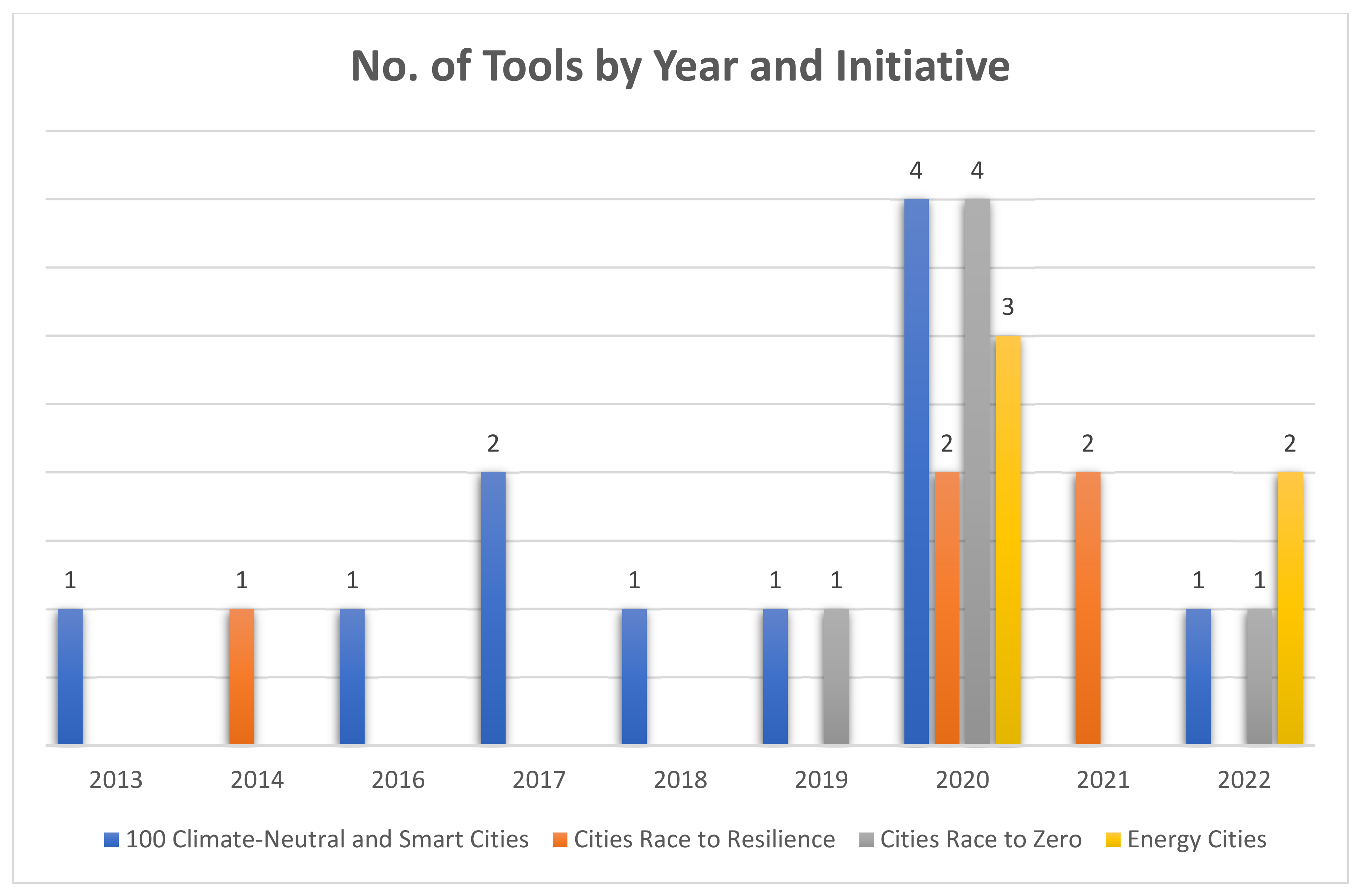

Appendix A. Procedural Governance Tools by Initiative

| Initiative | Organization(s)/Network(s) | Tool(s) | No. | Year |

| 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities | Rupprecht Consult (Germany), ICLEI Europe | Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan (SUMP) | 1 | 2013 |

| Participatory Budgeting Project (USA), NetZeroCities Knowledge Hub | Participatory budgeting (PB) | 1 | 2016 | |

| EuroCities, VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, Austrian Institute of Technology, City and R&I Partners | CITYkeys performance measurement framework | 1 | 2017 | |

| CARTIF Technology Centre (Spain), City and R&I Partners | Urban Regeneration Model (URM) | 1 | 2017 | |

| Global Covenant of Mayors, European Commission’s Joint Research Centre | Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) | 1 | 2018 | |

| European Smart Cities Marketplace, Norwegian University of Science and Technology | Climate-Neutral and Smart City Guidance Package (SCGP) | 1 | 2019 | |

| European Commission | European Climate Pact (ECP) | 1 | 2020 | |

| European Commission | Green City Accord (GCA) | 1 | 2020 | |

| ICLEI Europe, City of Mannheim, European Commission’s 100 Intelligent Cities Challenge | Local Green Deal (LGD) | 1 | 2020 | |

| European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation | Mission for 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities/Mission-Based Approach (100MC) | 1 | 2020 | |

| European Regions Research and Innovation Network | Climate City Contract (city input stage) (CCC) | (0) | 2021 | |

| ICLEI Europe | Climate City Contract conceptual model (CCC) | 1 | 2022 | |

| Energy Cities | Energy Cities | Local Participatory Agreement for the Climate Transition (Local PACT) | 1 | 2020 |

| Dutch Research Institute for Transitions, Energy Cities | X-Curve model + Uncovering systems tool (X-Curve + UST) | 2 | 2020 | |

| Doughnut Economics Action Lab (UK) | Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL) | 1 | 2022 | |

| Dutch Research Institute for Transitions, EIT Climate-KIC Transitions Hub | Transition legitimacy framework (TLF) | 1 | 2022 | |

| Cities Race to Zero | CPA Canada, C40 Knowledge Hub | Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework | 1 | 2019 |

| C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group | Climate Action Planning Framework + Vertically Integrated Action (CAP + VIA) | 2 * | 2020 | |

| ICLEI | Climate Neutrality Framework + GreenClimateCities guidance (CNF + GCC) | 2 | 2020 | |

| C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, Arup | Climate budgeting (CB) | 1 | 2022 | |

| Cities Race to Resilience | Arup, City Resilience Index, The Rockefeller Foundation | City Resilience Framework (CRF) | 1 | 2014 |

| C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group | Climate Action Planning Framework + Vertically Integrated Action (CAP + VIA) | 2 * | 2020 | |

| Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance, The World Bank | Enabling conditions framework to mobilize urban climate finance (ECF) | 1 | 2021 | |

| International Institute for Environment and Development | Principles for locally led adaptation (PLLA) | 1 | 2021 | |

| Total (27−2 = 25 unique tools) | 25 | |||

| * 2 tools are used in both Race to Zero and Race to Resilience. | ||||

References

- Stoddard, I.; Anderson, K.; Capstick, S.; Carton, W.; Depledge, J.; Facer, K.; Gough, C.; Hache, F.; Hoolohan, C.; Hultman, M.; et al. Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven’t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 653–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Geiges, A.; Gonzales-Zuñiga, S.; Hare, B.; Heck, S.; Helfmann, L.; Höhne, N.; Missirliu, A.; Hans, F.; Pelekh, N. Climate Action Tracker: Warming Projections Global Update. Climate Analytics, New Climate Institute, and the Institute for Essential Services Reform. November 2024. Available online: https://climateanalytics.org/publications/cat-global-update-as-the-climate-crisis-worsens-the-warming-outlook-stagnates (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2024: No More Hot Air … Please! UN Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2024 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Bulkeley, H.; Newell, P. Governing Climate Change, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattberg, P.; Kaiser, C.; Widerberg, O.; Stripple, J. 20 Years of global climate change governance research: Taking stock and moving forward. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2022, 22, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiarda, M.; Janssen, M.J.; Coenen, T.B.J.; Doorn, N. Responsible mission governance: An integrative framework and research agenda. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2024, 50, 100820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.; Clarke, A.; Tozer, L. Strategies and Governance for Implementing Deep Decarbonization Plans at the Local Level. Sustainability 2020, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, M.; Rayner, J. Chapter 7: Patching Versus Packaging in Policy Formulation: Assessing Policy Portfolio Design. 2017. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/display/edcoll/9781784719319/9781784719319.00013.xml (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Grönholm, S. Experimental governance and urban climate action—A mainstreaming paradox? Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrich, K. Chapter 8: Public Sector Innovation: Which Season of Public Sector Reform? 2023. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781800376748/book-part-9781800376748-12.xml (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Turnpenny, J.R.; Jordan, A.J.; Benson, D.; Rayner, T. Chapter 1: The Tools of Policy Formulation: An Introduction. 2015. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap-oa/edcoll/9781783477036/9781783477036.00011.xml (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Goyal, N.; Howlett, M. Types of learning and varieties of innovation: How does policy learning enable policy innovation? Policy Politics 2024, 52, 564–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, B.L. Policy learning governance: A new perspective on agency across policy learning theories. Policy Politics 2024, 52, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A.B. Governing the transnational: Exploring the governance tools of 100 Resilient Cities. In The Role of Non-State Actors in the Green Transition; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Capano, G.; Howlett, M. The Knowns and Unknowns of Policy Instrument Analysis: Policy Tools and the Current Research Agenda on Policy Mixes. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019900568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Cities. Systemic Changes in Governance. Equipping Local Governments for Realising Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities—Energy Cities. 2023. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/publication/systemic-changes-in-governance-equipping-local-governments-for-realising-climate-neutral-and-smart-cities%EF%BF%BC/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Bali, A.S.; Howlett, M.; Lewis, J.M.; Ramesh, M. Procedural policy tools in theory and practice. Policy Soc. 2021, 40, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Mission: Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe/climate-neutral-and-smart-cities_en (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- UCLG. Race to Zero & Race to Resilience: Global Campaigns for a Better Future. UCLG ASPAC. Available online: https://uclg-aspac.org/race-to-zero-race-to-resilience-global-campaigns-for-a-better-future/ (accessed on 12 July 2024).

- Chan, S.; van Asselt, H.; Hale, T.; Abbott, K.W.; Beisheim, M.; Hoffmann, M.; Guy, B.; Höhne, N.; Hsu, A.; Pattberg, P.; et al. Reinvigorating International Climate Policy: A Comprehensive Framework for Effective Nonstate Action. Glob. Policy 2015, 6, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T. The Role of Sub-State and Nonstate Actors in International Climate Processes. Chatham House: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.geg.ox.ac.uk/publication/role-sub-state-and-nonstate-actors-international-climate-processes (accessed on 21 October 2022).

- Bäckstrand, K.; Kuyper, J.W.; Linnér, B.-O.; Lövbrand, E. Non-state actors in global climate governance: From Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environ. Politics 2017, 26, 561–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. ‘Our Struggle for Global Sustainability Will Be Won or Lost in Cities’, Says Secretary-General, at New York Event. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2012/sgsm14249.doc.htm (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- UNFCCC. Guterres: ‘Cities Are Where the Climate Battle Will Largely Be Won or Lost’. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/guterres-cities-are-where-the-climate-battle-will-largely-be-won-or-lost (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- World Bank. Cities Key to Solving Climate Crisis. World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/05/18/cities-key-to-solving-climate-crisis (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Jernnäs, M.; Lövbrand, E. Accelerating Climate Action: The Politics of Nonstate Actor Engagement in the Paris Regime. Glob. Environ. Politics 2022, 22, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Boran, I.; van Asselt, H.; Ellinger, P.; Garcia, M.; Hale, T.; Hermwille, L.; Mbeva, K.L.; Mert, A.; Roger, C.B.; et al. Climate Ambition and Sustainable Development for a New Decade: A Catalytic Framework. Global Policy 2021, 12, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GGCA. Galvanizing the Groundswell of Climate Actions. Available online: http://www.climategroundswell.org (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- GGCA. The Future of Global Climate Action in the UNFCCC: A Galvanizing the Groundswell of Climate Actions ‘Online Atelier’. UNFCCC. May 2020. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/552be32ce4b0b269a4e2ef58/t/5f0aea8fe9cddf559fb3a650/1594550927666/35+Summary+report+-+Online+Atelier+on+Global+Climate+Action.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Climate Ambition and Sustainable Development for a New Decade: A Catalytic Framework—Chan—2021—Global Policy—Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.surrey.idm.oclc.org/doi/full/10.1111/1758-5899.12932 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- UNFCCC. The 5th P (Persuade) Handbook; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.alliancesforclimateaction.org/pdfs/The-5th-P-Handbook-1.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Chan, S.; Hale, T.; Deneault, A.; Shrivastava, M.; Mbeva, K.; Chengo, V.; Atela, J. Assessing the effectiveness of orchestrated climate action from five years of summits. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Climate Institute. Global Climate Action from Cities, Regions and Businesses. June 2021. Available online: https://newclimate.org/resources/publications/global-climate-action-from-cities-regions-and-businesses-2021 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- ICLEI. Race to Zero, Race to Resilience, and New Covenant Europe Commitments: FAQ DOCUMENT TO GUIDE CITIES. 2021. Available online: https://iclei-europe.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Our_Work/Advocacy/ICLEI-COM-RTZ-faq.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- UNFCCC. Joining Cities Race to Resilience: A Step-by-Step Guide for Cities. Available online: https://racetozero.unfccc.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Cities-RtR-Step-by-Step-guide-24-August-2021.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- UNFCCC. Race to Zero Criteria. Climate Champions. Available online: https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/system/criteria/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Bulkeley, H. The condition of urban climate experimentation. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2188726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H.; Broto, V.C. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Gov. Exp. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2013, 38, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Proposed Mission: 100 Climate-Neutral Cities by 2030—By and for the Citizens: Report of the Mission Board for Climate-neutral and Smart Cities. 2020. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/bc7e46c2-fed6-11ea-b44f-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search (accessed on 22 December 2022).

- NetZeroCities. WP13, D13.1, Report on City Needs, Drivers and Barriers Towards Climate Neutrality. May 2022. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/results-publications/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- NetZeroCities. Mission Platform website. NetZeroCities. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/ (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- European Commission. European Missions—Info Kit for Cities. 21 November 2021. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/document/download/cb258381-77d5-435a-8b25-9a590795dc9e_en?filename=ec_rtd_eu-mission-climate-neutral-cities-infokit.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- C40 Cities. C40 Cities—A Global Network of Mayors Taking Urgent Climate Action. C40 Cities. Available online: https://www.c40.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- ICLEI. ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. ICLEI. Available online: https://iclei.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- GCoM. Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy. Global Covenant of Mayors. Available online: https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Bulkeley, H.; Betsill, M.M. Revisiting the urban politics of climate change. Environ. Politics 2013, 22, 136–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.; Haindlmaier, G. The Evolving European Landscape of National Cities Mission Support Structures. Cluj-Napoca, Romania. 18 December 2023. Available online: https://dutpartnership.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/CapaCITIES_NetZeroCities_Cluj18122023.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Johansson, H.; EuC, M.G.P.; Krajewska, O.; Aschan, C.; EnC, A.M.; RCN, A.S. D1.7 National/Regional CCC Engagement Cluster Situation Report. NetZeroCities. October 2021. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/D1.7_National-Regional-CCC-Engagement-Cluster-Situation-Report-1.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- UK100. UK100|An Ambitious Network of 100+ UK Local Authorities|UK100. Available online: https://www.uk100.org/about (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Viable Cities. About Viable Cities. Viable Cities. Available online: https://viablecities.se/en/om/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- citiES 2030. Available online: https://cities2030.es/en/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- CDP. Overview of CDP-ICLEI Track Cities Questionnaire. Available online: https://cdn.cdp.net/cdp-production/comfy/cms/files/files/000/009/079/original/CDP-ICLEI_Track_Questionnaire_Changes_Overview_2024.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- GCoM. 19. How is Progress Monitored and Reported in the GCoM Initiative? Global Covenant of Mayors. Available online: https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/faq/how-is-progress-monitored-and-reported-in-the-gcom-initiative/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- GCoM. Global Common Reporting Framework. November 2022. Available online: https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/our-initiatives/data4cities/common-global-reporting-framework/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Mondal, R.; Bresciani, S.; Rizzo, F. What Cities Want to Measure: Bottom-Up Selection of Indicators for Systemic Change Toward Climate Neutrality Aligned with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 40 European Cities. Climate 2024, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NetZeroCities. Climate Transition Map. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/ClimateTransitionMap (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- European Commission. Creating National Governance Structures for the Implementation of EU Missions: Mutual Learning Exercise on EU Missions Implementation at National Level: First Thematic Report. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. January 2024. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/fd29d7a1-b103-11ee-b164-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Bellinson, R.; Chu, E. Learning pathways and the governance of innovations in urban climate change resilience and adaptation. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2019, 21, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy: Challenges and Opportunities. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper. September 2017. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/sites/public-purpose/files/moip-challenges-and-opportunities-working-paper-2017-1.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Mazzucato, M. Mission-oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities. Ind. Corp. Change 2018, 27, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabb, K.; McCormick, K.; Mujkic, S.; Anderberg, S.; Palm, J.; Carlsson, A. Launching the Mission for 100 Climate Neutral Cities in Europe: Characteristics, Critiques, and Challenges. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 3, 817804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen-Burge, C. Interview with Chris Skidmore: Learning the Lessons of the UK’s Net Zero Transition. Climate Champions. Available online: https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/learning-the-lessons-of-the-uks-net-zero-transition/ (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Skidmore, C. Mission Zero: Independent Review of Net Zero. January 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-net-zero (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- UK100. Zero in: Accelerating Climate Action. April 2024. Available online: https://www.uk100.org/publications/new-report-zero-accelerating-climate-action (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- NetZeroCities. Knowledge Repository. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- NetZeroCities. Twinning Learning Programme. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/twinning-learning-programme/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- NetZeroCities. Cities Mission Conference 2025: Harnessing City Successes—Vilnius. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/cities-mission-conference-2025/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Kaufmann, P.; Kofler, J.; Harding, R. Study Supporting the Assessment of EU Missions and the Review of Mission Areas: Mission Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Assessment Report. Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, European Commission. July 2023. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/35567 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Energy Cities. Our Vision: Energy Cities Empowers Cities and Citizens to Shape and Transition to Future Proof Cities. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/vision-mission/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- World Bank. Future-Proofing Cities: How Our Prosperity Tomorrow Depends on Transforming Cities Today. World Bank Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/voices/future-proofing-cities-how-our-prosperity-tomorrow-depends-transforming-cities-today (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Energy Cities. Local Alliance’s Vision for a Future-Proofed EU Budget: Empowering Local Communities. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/policy/local-alliances-vision-for-a-future-proofed-eu-budget-empowering-local-communities/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- ZOE. A Compass Towards 2030: Navigating the EU’s Economy Beyond GDP by Applying the Doughnut Economics Framework. ZOE Institute for Future-Fit Economies. Available online: https://zoe-institut.de/en/publication/a-compass-towards-2030/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Energy Cities and DRIFT. What Is TOMORROW? Available online: https://www.citiesoftomorrow.eu/what-tomorrow/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- De Geus, T.; Wittmayer, J.M.; Vogelzang, F. Biting the bullet: Addressing the democratic legitimacy of transition management. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2022, 42, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TOMORROW and DRIFT. Designing Participatory Processes for Just and Climate-Neutral Cities: Methodological Guidelines for Using Transition Management. 2022. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/publication/designing-participatory-processes-for-just-and-climate-neutral-cities/ (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- Energy Cities. Future-Proof Local Governance: Setting up Long-Term Local Partnerships & Trying out New Participatory Processes to Transform Local Ecosystems. Energy Cities. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/hub/local-governance/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Energy Cities and DRIFT. The TOMORROW Project Has Ended, but the Cities’ Journeys Have Just Begun: Key Takeaways from the 3-Year Project. January 2023. Available online: https://www.citiesoftomorrow.eu/news/tomorrow-project-has-ended-cities-journeys-have-just-begun-key-takeaways-3-year-project/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Energy Cities. Circular Economy and Doughnut Economics. Energy Cities. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/circular-economy-and-doughnut-economics/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Energy Cities. Resource-Wise & Socially Just Local Economies. Energy Cities. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/hub/local-economies/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- NetZeroCities. Futureproofed Webinar: Zero-Emission Strategies for Cities. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/resource-4040 (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Georgiadou, M.C.; Hacking, T.; Guthrie, P. A conceptual framework for future-proofing the energy performance of buildings. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, N.; Savage, R. Future Proofing Cities: Risks and Opportunities for Inclusive Urban Growth in Developing Countries; Atkins: Epsom, UK, 2012. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/future-proofing-cities-risks-and-opportunities-for-inclusive-urban-growth-in-developing-countries (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Wilson, B.D. Futureproof City: Ten Immediate Paths to Urban Resilience, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Futureproof-City-Ten-Immediate-Paths-to-Urban-Resilience/Wilson/p/book/9780367631956?srsltid=AfmBOooEEBjjlTKTUNna7awlfzBL8P9eXWd3UKMgFUj46AhIATyp98-L (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Wilson, B.D. An outline to futureproofing cities with ten immediate steps. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2018, 171, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEAL. Cities & Regions: Let’s Get Started—A Guide for Local and Regional Governments Offering Nine Pathways to Engage with Doughnut Economics. 2023. Available online: https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools/210 (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- DEAL. Doughnut Unrolled: Data Portrait of Place. July 2023. Available online: https://doughnuteconomics.org/tools/doughnut-unrolled-data-portrait-of-place (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- OECD. Reaching Net Zero: Do Mission-Oriented Policies Deliver on Their Many Promises? March 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-science-technology-and-innovation-outlook-2023_0b55736e-en/full-report/component-9.html (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Bansard, J.S.; Pattberg, P.H.; Widerberg, O. Cities to the rescue? Assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2017, 17, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabb, K.; McCormick, K. Achieving 100 climate neutral cities in Europe: Investigating climate city contracts in Sweden. NPJ Clim. Action 2023, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Roger, C. Orchestration and transnational climate governance. Rev. Int. Organ. 2014, 9, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilvers, J.; Kearnes, M. Remaking Participation: Science, Environment and Emergent Publics; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, J.J. Remaking Political Institutions: Climate Change and Beyond, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, E.; Christie, I. The Remaking of Institutions for Local Climate Governance? Towards Understanding Climate Governance in a Multi-Level UK Local Government Area: A Micro-Local Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. Organisational Architecture: Ideas for an Emergent Discipline. August 2022. Available online: https://www.geoffmulgan.com/post/mesh-organisational-archicture-theory (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Pahl-Wostl, C. A conceptual framework for analysing adaptive capacity and multi-level learning processes in resource governance regimes. Glob. Environ. Change 2009, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.J.; Moore, B. Durable by Design?: Policy Feedback in a Changing Climate; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torney, D. Deliberative mini-publics and the European Green Deal in turbulent times: The Irish and French climate assemblies. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buylova, A.; Nasiritousi, N.; Bergman, J.; Sanderink, L.; Wickenberg, B.; Flores, C.C.; McCormick, K. Bridging silos through governance innovations: The role of the EU cities mission. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 6, 1463870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deslatte, A.; Stokan, E. Sustainability Synergies or Silos? The Opportunity Costs of Local Government Organizational Capabilities. Public Adm. Rev. 2020, 80, 1024–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Governance in Complexity—Sustainability Governance Under Highly Uncertain and Complex Conditions. June 2024. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/governance-in-complexity-sustainability-governance (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Loorbach, D.A. Designing radical transitions: A plea for a new governance culture to empower deep transformative change. City Territ. Arch. 2022, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tõnurist, P.; Hanson, A. Anticipatory Innovation Governance: Shaping the Future Through Proactive Policy Making; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/anticipatory-innovation-governance_cce14d80-en.html (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Sabel, C.F.; Victor, D.G. Fixing the Climate: Strategies for an Uncertain World; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sabel, C.F. Beyond Principal-agent Governance: Experimentalist Organizations, Learning and Accountability; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wanzenböck, I.; Frenken, K. The subsidiarity principle in innovation policy for societal challenges. Glob. Transit. 2020, 2, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.T.; Stiftel, B. Adaptive Governance and Water Conflict: New Institutions for Collaborative Planning; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin, B.C.; Gosnell, H.; Cosens, B.A. A decade of adaptive governance scholarship: Synthesis and future directions. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 56. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269646 (accessed on 13 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Metagoverning Collaborative Innovation in Governance Networks. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 47, 826–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, C.F.; Zeitlin, J. Learning from Difference: The New Architecture of Experimentalist Governance in the EU. Eur. Law J. 2008, 14, 271–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkeley, H. Cities and the Governing of Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuenfschilling, L.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Coenen, L. Urban experimentation & sustainability transitions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, D.P.M.; Martín-López, B.; Wiek, A.; Bennett, E.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Horcea-Milcu, A.I.; Lang, D.J. Scaling the impact of sustainability initiatives: A typology of amplification processes. Urban Transform. 2020, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, E.; Kundu, O.; Ortega-Argiles, R.; Harbour, M. 17: Innovation-promoting impacts of public procurement. In Handbook of Innovation and Regulation; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781800884472/b-9781800884472.00026.xml (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Kivimaa, P.; Hildén, M.; Huitema, D.; Jordan, A.; Newig, J. Experiments in climate governance—A systematic review of research on energy and built environment transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, S.; Berg, A.; Annala, M. Dynamics of experimental governance: A meta-study of functions and uses of climate governance experiments. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. Multi-level Governance and Multi-level Metagovernance: Changes in the European Union as Integral Moments in the Transformation and Reorientation of Contemporary Statehood. In Multi-Level Governance; Bache, I., Flinders, M., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, E.; Torfing, J. Making Governance Networks Effective and Democratic Through Metagovernance. Public Adm. 2009, 87, 234–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhurst, N.; Chilvers, J. Mapping diverse visions of energy transitions: Co-producing sociotechnical imaginaries. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NetZeroCities. WP1, D1.3, Climate-neutral City Contract Concept. July 2022. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/results-publications/ (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- RUGGEDISED. Governance, Trust and Smart City Business Models: The Path to Maturity for Urban Data Platforms. 2020. Available online: https://ruggedised.eu/smart-solutions/urban-data-platforms/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Energy Cities. Local PACTs—How Municipalities Create Their Own COP21. 2021. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/publication/local-pacts/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- DRIFT. Transition Management in the Urban Context: Guidance Manual. November 2016. Available online: https://drift.eur.nl/app/uploads/2016/11/DRIFT-Transition_management_in_the_urban_context-guidance_manual.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- DRIFT and EIT Climate-KIC. X-Curve: A Sense-Making Tool to Foster Collective Narratives on System Change. February 2022. Available online: https://drift.eur.nl/app/uploads/2023/08/X-Curve-booklet-DRIFT-EIT-Climate-KIC-2022-1.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Van Mierlo, B.C.; Regeer, B.; van Amstel, M.; Arkesteijn, M.C.M.; Beekman, V.; Bunders, J.F.G.; de Cock Buning, T.; Elzen, B.; Hoes, A.C.; Leeuwis, C. Reflexive Monitoring in Action. A Guide for Monitoring System Innovation Projects. Communication and Innovation Studies, WUR; Athena Institute, VU, Wageningen/Amsterdam. 2010. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/395732 (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Beurden, J.B.-V.; Kallaos, J.; Gindroz, B.; Costa, S.; Riegler, J. Smart City Guidance Package (SCGP)—A Roadmap for Integrated Planning and Implementation of Smart City Projects. European Innovation Partnership Smart Cities and Communities (EIP-SCC). 2019. Available online: https://smart-cities-marketplace.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/2019/smart-city-guidance-package (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Energy Cities. Agenda for a Transformative Decade—Energy Cities. 2021. Available online: https://energy-cities.eu/publication/agenda-for-a-transformative-decade/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Beurden, J.B.-V.; Kruizinga, E.; de Almeida, J.R.; Kallaos, J.; Gindroz, B. Climate Neutral & Smart City Guidance Package—A Summary: Fast-Tracking Financially Viable Projects in an Integrated and Inclusive Way. 2020. Available online: https://smart-cities-marketplace.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/2020/climate-neutral-smart-city-guidance-package-summary (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- PBP. PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING: Next Generation Democracy. 2016. Available online: https://www.oidp.net/docs/repo/doc283.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- TOMORROW. Vilawatt: A New form of Governance PARTNERSHIP—Viladecans, Spain. 2019. Available online: https://www.citiesoftomorrow.eu/resources/toolbox/factsheets/vilawatt-new-form-governance-partnership-viladecans/ (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- REMOURBAN. Urban Regeneration Model: A Practical Toolkit to Transform Your City into a Smart and Sustainable Ecosystem. 2020. Available online: http://www.remourban.eu/technical-insights/best-practices-e-book/best-practices-e-book.kl (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- PBP. Participatory Budgeting Project—PB Scoping Toolkit: A Guide for Officials & Staff Interested in Starting PB. February 2020. Available online: https://www.participatorybudgeting.org/launch-pb/ (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- CITYkeys. City Handbook to Performance Measurement. City of Zagreb. 2017. Available online: https://eko.zagreb.hr/UserDocsImages/arhiva/Slike/projekt%20CITYKeys/rezultati/CITYkeysD46Cityhandbooktoperformancemeasurementweb.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Material Economics. Understanding the Economic Case Decarbonising Cities—Why Economic Case Analysis for City Decarbonisation is Crucial. 2020. Available online: https://materialeconomics.com/latest-updates/understanding-the-economic-case-for-decarbonizing-cities (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- ERRIN. Launch of the EU Mission on Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities—Concerns from Cities. ERRIN. 2021. Available online: https://errin.eu/system/files/2021-11/211118_Cities%20Mission_Letter%20on%20cities%20concerns.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- REMOURBAN. D1.19: Urban Regeneration Model—WP1, Task 1.5. 2017. Available online: http://www.remourban.eu/technical-insights/deliverables/urban-regeneration-model.kl (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Velten, E.K.; Duwe, M.; Schöberlein, P.; Stüdeli, L.M.; Evans, N.; Felthöfer, C.; Gardiner, J.; Tarpey, J.; de la Vega, R. Flagship Report: State of EU Progress to Climate Neutrality. An Indicator-Based Assessment Across 13 Building Blocks for a Climate Neutral Future. European Climate Neutrality Observatory (ECNO). June 2023. Available online: https://www.ecologic.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2023/50132-ECNO-Flagship-report-State-of-EU-progress-to-climate-neutrality-web.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- NetZeroCities. Quick Read: Climate City Contracts. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/QR-CCC (accessed on 11 June 2024).

- NetZeroCities. Pilot Cities Programme. NetZeroCities. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/pilot-cities-programme/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Complexity and Transition Management. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, H.; Bendlin, L.; Fenton, P. Shaping local response—The influence of transnational municipal climate networks on urban climate governance. Urban Clim. 2018, 24, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouldson, A.; Sudmant, A.; Khreis, H.; Papargyropoulou, E. The Economic and Social Benefits of Low-Carbon Cities: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. June 2018. Available online: http://newclimateeconomy.net/content/cities-working-papers (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- NetZeroCities. NetZeroCities Pilot Cities Programme Guidebook. June 2022. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/PilotGuideBook (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Caulier-Grice, J.; Davies, A.; Patrick, R.; Norman, W. Defining Social Innovation. The Young Foundation, Deliverable of the Project: “The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe” (TEPSIE). May 2012. Available online: https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/TEPSIE.D1.1.Report.DefiningSocialInnovation.Part-1-defining-social-innovation.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation. In Social Innovator Series: Ways to Design, Develop and Grow Social Innovation; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.youngfoundation.org/our-work/publications/the-open-book-of-social-innovation/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- NetZeroCities. Climate Transition Map Series|Activate an Inclusive Ecosystem for Change. 27 September 2022. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/resource-3066 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, D.; Cartron, E.; Fischer, L.; Beunderman, J.; Soberón, M.; Urrutia, K.; Dorst, H.; Carvajal, A.; Griffin, H. Transition Team Playbook: Orchestrating a Just Transition to Climate Neutrality. NetZeroCities. September 2022. Available online: https://netzerocities.app/TransitionPlaybook (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Bridgforth, J. What is Mission-Oriented Policy? Mission Action Lab. Available online: https://oecd-missions.org/key-topics/what-is-mission-oriented-policy/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- IPCC. Annex I: Glossary—Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/glossary/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- NetZeroCities. Spotlight Series: Cities as Ecosystems for Social Innovation. Available online: https://netzerocities.eu/2023/03/17/spotlight-series-cities-as-ecosystems-for-social-innovation/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Innovage. Defining Social Innovation. Available online: https://innovage.sites.sheffield.ac.uk/social-innovations/defining-social-innovation (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Anheier, H.K.; Korreck, S. Governance Innovations. In The Governance Report 2013; in The Governance Report Series; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 83–116. Available online: https://www.hertie-school.org/en/governancereport/govreport-innovations (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Gerrits, L.; Edelenbos, J. Management of sediments through stakeholder involvement: The risks and value of engaging stakeholders when looking for solutions for sediment-related problems. J. Soils Sediments 2004, 4, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Quality of Public Administration: A Toolbox for Practitioners. Principles and Values of Good Governance; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/593135 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Thijs, N.; Staes, P. European Primer on Customer Satisfaction Management. European Institute of Public Administration & European Public Administration Network. May 2008. Available online: https://www.venice.coe.int/images/SITE%20IMAGES/Publications/14th_UniDemMed_Thijs_EUPAN_CustomerSatisfaction_English__FINAL.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

| Characteristics | Cities Race to Zero Campaign | Cities Race to Resilience Campaign | 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities Mission | Energy Cities | Mission Zero Coalition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year Established/ Leadership | 2020/United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change + 7 partners | 2021/United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change + 8 partners | 2021/European Commission + 34 NetZeroCities partners | 1990/Energy Cities + leading: CoM Europe (2008), Eastern Europe/South Caucasus (2011) offices | 2023/Former UK Energy Minister + 27 member organizations |

| Focus | Mitigation and adaptation | Mitigation and adaptation | Primarily mitigation | Mitigation and adaptation | Primarily mitigation |

| Mobilizing Concept | Race to Zero | Race to Resilience | Mission-oriented innovation | Future-proof cities | Mission Zero |

| Cities Involved | 1143 cities globally | 733 cities globally | 112 cities; 27 EU, 8 non-EU countries | 174 cities; 22 EU, 10 non-EU countries | 112 UK100 local authorities |

| Approach and Time Horizon | Engage subnational and non-state signatories via partners to accelerate actions to half global emissions by 2030 and become net-zero by 2050 at the latest while ensuring a healthy, resilient, zero-carbon recovery | Engage subnational and non-state actors to strengthen 4 billion vulnerable people’s resilience to climate risks by 2030; ensure adaptation/resilience are fully integrated into local planning | Help 100 EU and 12 Horizon Europe-associated country cities become climate-neutral by 2030 and generate the insights, structures, and approaches that help all EU cities become climate-neutral by 2050 | Support member cities via learning hubs to reach climate neutrality by 2050 via systems approaches to realizing decarbonized, resilient cities: (a) access to affordable, secure, and sustainable energy; (b) local development aligned with SDGs | Net-zero proposed as a green growth opportunity; UK must seize this to remain a leader/competitor in the global “race” and reach net-zero by 2050 |

| Governance Model | Vertical integration of subnational and non-state net-zero actions to better align with NDCs and global SDGs | Vertical integration of subnational and non-state resilience actions to better align with NDCs and global SDGs | Multi-level governance using co-created Climate City Contracts focused on innovative “holistic” city governance and encouraging national support platforms for cities | Multi-level governance via policy dialog and multi-level, city-to-city cooperation to create favorable conditions to translate policies/actions across places/levels (EU to local) | Alignment of governance structures to harness public and private climate action via ten priority missions to 2035 |

| Good Governance | Harness the “groundswell” of voluntary targets via tools (e.g., campaigns, standard setting, and regulations) to create a high-integrity governance ecosystem and shape global economic “ground rules” | New, inclusive approaches that balance economic and well-being values, co-designing the vision/choices for a holistic strategy that integrates climate, social, and health objectives | A new city governance based on (a) a holistic approach to foster innovation and deployment; (b) a matrix of integrated and multi-level governance; and (c) deep, continuous stakeholder collaboration | Governance changes (revised economic rules and adapted legal frameworks) should enable a “local & sustainable first” approach to future-proof economies | A UK-wide, whole economy approach that is (a) participatory, delivery-based; (b) long-term to provide the clarity, certainty, and direction for net-zero |

| Initiative | Cluster | No. of Documents | No. of Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities | 1 | 21 | 11 |

| Energy Cities | 2 | 10 | 5 |

| Cities Race to Zero | 3 | 29 | 6 |

| Cities Race to Resilience | 4 | 29 | 5 * |

| Reflexivity | Enabling/Embedding | Participatory | Adaptivity | Integrative | Radicality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a. Internal and external listening and feedback loops (Mulgan 2022; Pahl-Wostl 2009) [94,95] | 2a. Deep and continuous dialog and engagement (Jordan and Moore 2020) [96] | 3a. Inclusivity (cross-sectoral, widening/deepening) (Torney 2021) [97] | 4a. Agility (Wegrich 2023) [10] | 5a. Long and short term | 6a. Holistic system innovation |

| 1b. Organizational development (Buylova et al., 2025; Deslatte and Stokan 2020) [98,99] | 2b. Awareness and education | 3b. Value-driven (Democracy, justice, trust, equity) (European Environment Agency 2024) [100] (p. 43) | 4b. Flexibility (change from best and worst practices) | 5b. Collective decision-making | 6b. Radical core/radical collaboration (de Geus et al., 2022; Loorbach 2022) [74,101] |

| 1c. Institutional restructuring and change (Tõnurist and Hanson 2020) [102] | 2c. Connecting learning and policy (Sabel 2004; Sabel and Victor 2022) [103,104] | 3c. Citizen-centric (Wanzenböck and Frenken 2020) [105] | 4c. New tools, working cultures, and models (Scholz and Stiftel 2005; Chaffin et al., 2014) [106,107] | 5c. Multi-modal collaborative roles (Sørensen and Torfing 2017) [108] | 6c. Experimental governance and finance (Sabel and Zeiling 2008) [109]; (Fünfschilling et al., 2019; Bulkeley 2010) [110,111] |

| 1d. Monitoring, evaluation, and learning (Mondal et al., 2024) [55] | 2d. Anticipatory measures for embedding (Lam et al., 2020) [112] | 3d. Multi-stakeholder partnerships (Uyarra et al., 2023) [113] | 4d. Adapting to new insights/risks (Kivimaa et al., 2017; Laakso, Berg, and Annala 2017) [114,115] | 5d. Multiple change levers (economic, social, carbon) and levels of governance (Jessop 2004; Sørensen and Torfing 2009) [116,117] | 6d. Alternative visions and voices (Longhurst and Chilvers 2019) [118] |

| Governance Concept | Description | Application | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-level perspective (Geels & Schot 2007) [147] | Innovation niches interact with and disrupt existing governance regimes, incumbent technologies, and socio-technical landscapes to eventually stabilize and become part of the dominant regimes/landscapes | Model inspired work to connect innovative experiments for participatory, just, and climate-neutral transformations at city level with national/EU platforms (e.g., Viable Cities, NetZeroCities) and a pillar of the Cities Mission’s “new city governance” | Describes dynamics of how governance innovations can become embedded but no means of open innovation management/iterations within niches/approaches |

| Transition management (Rotmans and Loorbach 2009; Loorbach et al., 2017) [139,140] | A reflexive change model to accelerate transitions via fundamental change in ways of doing (practices), ways of thinking (cultures), and ways of organizing (structures) based on a change management cycle used to implement strategies to influence societal transitions | Model inspired the design of more open, participatory models of governance, starting with a core transition team led by cities and expanding to involve key stakeholders and citizens (see [148]) | Describes the organizational change model for relating and developing collaborative transition arenas steered by a transition team but does not account specifically for measuring and refining processes and interventions |

| Mission approach (Mazzucato 2017, 2018) [59,60] | An innovation-led policy approach to structure wicked problems/grand societal challenges into clear, targeted “missions” through political agenda setting and civic engagement in order to co-create, shape, and fix markets to be better aligned with public goods using a portfolio of projects and bottom-up experimentation | The systemic innovation approach (see [149]) inspired the EU to structure its research and innovation funding around Missions, e.g., Cities Mission, with the public sector co-creating interventions that cut across sectoral systems to unlock pathways and investment towards climate neutrality | Sets out a broad direction of travel to open up governance to more participatory/co-creative processes for developing public value interventions/policies but no specificity in dealing with the added complexity and administration of the stakeholder/civic engagement and management required |

| Institutional design of transnational municipal networks (Bansard et al., 2017; Bush, Bendlin and Fenton 2018) [88,141] | Governance through the lens of the institutional design of transnational municipal networks (TMNs) and its connection to quantified emission reduction targets/bridging the climate mitigation action gap left by inaction at national/global levels | This body of work has spurred greater attention to monitoring, reporting, and verification of climate mitigation actions of TMN member cities, for example, tracking sector-based interventions to reduce emissions measured by GHG indicators on platforms: MyCovenant (GCoM), CDP-ICLEI Track, etc. | Helpful in explaining the role, dynamics, and functions of TMNs in influencing the global climate governance regime but does not account for evaluating governance processes at the local level, including relational dynamics between different levels of governance |

| Co-benefits (Gouldson et al., 2018) [142] | The positive effects that a policy or measure aimed at one objective might have on other objectives, irrespective of the net effect on overall social welfare (IPCC, 2018) [148] (p. 32), [150]; Ancillary impacts or positive side-effects of, and integral to, climate mitigation or adaptation interventions [143] | Cities develop an economic case for decarbonizing using a portfolio approach: A dynamic set of complementary climate actions (e.g., policies, regulatory and organizational changes, programs, projects, investments) that deliberately looks to involve multiple actors and to unlock synergies and co-benefits between actions and across sectors | Helpful in supporting efforts to mainstream climate action in cities and leverage climate-related finance but ignores the political dimensions and power relations of how action portfolios are developed and governed |

| Social innovation (Caulier-Grice et al., 2012) [144] | A collaborative and human-centric approach for cities to cultivate an enabling ecosystem for net-zero by and with residents to co-design new ideas and solutions and change norms and systems of governance [151]; a form of innovation that is social in its ends and its means (Murray et al., 2010) [145] (also see [143,152]) | Cities use learning-by-doing approaches that incorporate prototyping and quick experimentation alongside citizens via city labs or other participatory processes designed to meaningfully include end users/beneficiaries, address unmet local challenges, and incentivize mobilization around net-zero | Theorizes new relations between cities and citizens as a bottom-up complementarity to top-down approaches to net-zero but ignores the inherent power relations (similar to co-benefits) and does not account for the risks/conflicts associated with participation |

| Governance innovation (Anheier and Korreck, 2013) [153] | Novel rules, regulations, and approaches that seek to address a public problem in more efficacious and effective ways lead to better policy outcomes and enhance legitimacy [143] (p. 45) | Transition teams [148] co-led by cities transform traditional top-down governance to a network governance model and embrace a supportive, facilitator role to (1) build capacity across the local ecosystem of public, private, and civic actors; (2) co-develop and co-implement climate actions; and (3) build an added level of trust, alignment, and openness | Descriptive of embracing a more open/networked form of governance in novel ways connected to public problems and theorizes a general approach to co-developing solutions but lacks details of how to address the additional complexity |

| Radical collaboration (Net Zero Cities, 2022) [146] | Collaboration that is built into decision-making from the ground up, where stakeholders and citizens are seen as co-deciders and co-producers of outcomes rather than just as consultees. It needs a long-term commitment to building a culture of openness in government and other bodies and a financial commitment to supporting the social and digital infrastructure that can underpin that long-term engagement [143] (p. 46). | Cities employ long-term stakeholder and citizen engagement approaches that are designed to redefine the relationship and responsibility between cities and stakeholders/citizens towards a shared ownership model designed to activate an inclusive ecosystem for change (climate transition map) by building trust, ensuring transparency, continuously aligning actors’ expectations, and brokering compromises where needed via collective visioning (Net Zero Cities 2022) [146]. | Provides a general framing that local governments should actively engage in delegating, co-operating, and facilitating styles of governance (Gerrits and Edelenbos 2004) [154] in line with EU public administration best practices (Thijs, N., and Staes, P., 2008; Hauser, F. (Ed.), 2017) [155,156] but ignores political/power dynamics (like co-benefits and social innovation) and the resources/capacity constraints of such engagement processes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terwilliger, J.; Christie, I. Cities and Governance for Net-Zero: Assessing Procedures and Tools for Innovative Design of Urban Climate Governance in Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2698. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062698

Terwilliger J, Christie I. Cities and Governance for Net-Zero: Assessing Procedures and Tools for Innovative Design of Urban Climate Governance in Europe. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2698. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062698

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerwilliger, Joel, and Ian Christie. 2025. "Cities and Governance for Net-Zero: Assessing Procedures and Tools for Innovative Design of Urban Climate Governance in Europe" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2698. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062698

APA StyleTerwilliger, J., & Christie, I. (2025). Cities and Governance for Net-Zero: Assessing Procedures and Tools for Innovative Design of Urban Climate Governance in Europe. Sustainability, 17(6), 2698. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062698