The Changes in Grassland Animal Husbandry and Herdsmen’s Life in the Qinghai Pastoral Area of China Based on the Perspective of Changes in the Grassland Property Rights System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Areas and Methods

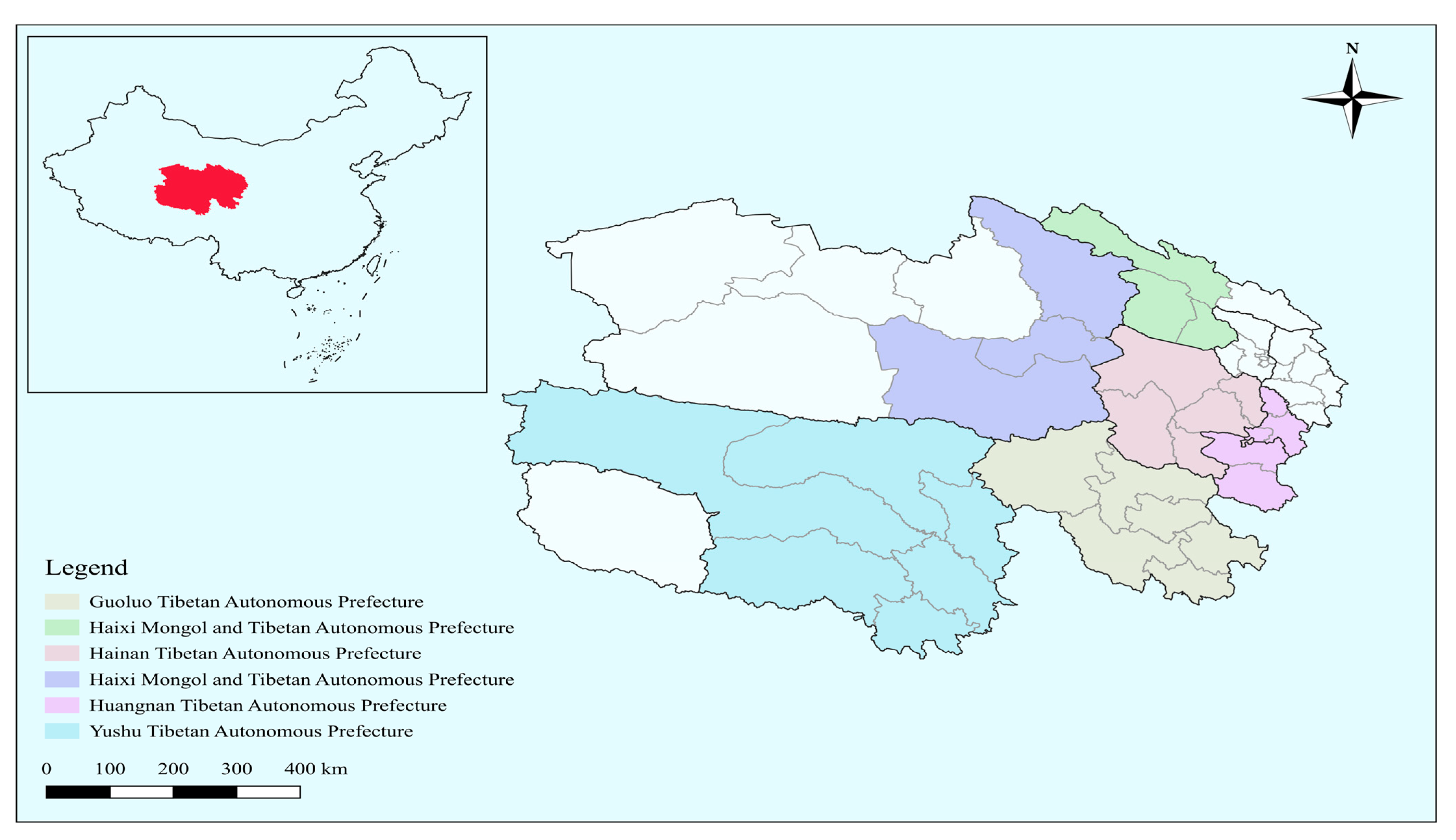

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Analyses

3. Results

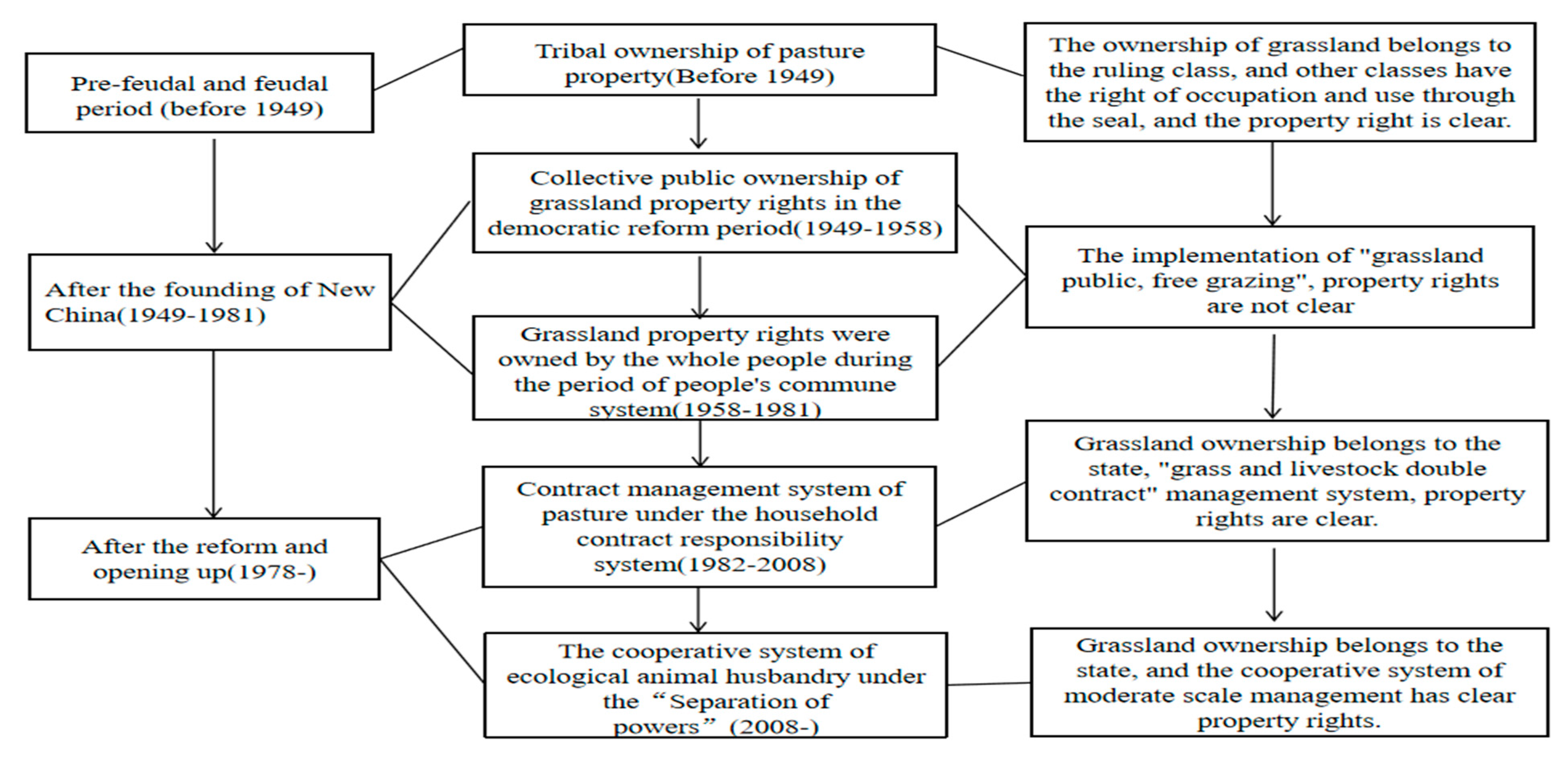

3.1. Historical Evolution of Grassland Property Rights System in Qinghai Province

3.1.1. Tribal Ownership System of Grassland Property Rights in Pre-Feudal and Feudal Society

3.1.2. Collective Public Ownership of Grassland Property Rights After the Founding of New China

- Collective public ownership of grassland property rights during the democratic reform period.

- Grassland property rights were owned by the whole people during the period of people’s commune

3.1.3. The Household Contract Management Responsibility System of Grassland Property Rights After the Reform and Opening-Up

3.1.4. Ecological Animal Husbandry Cooperative System Under “Three Rights Separation”

3.2. The Influence of the Property Right System on Grassland Animal Husbandry

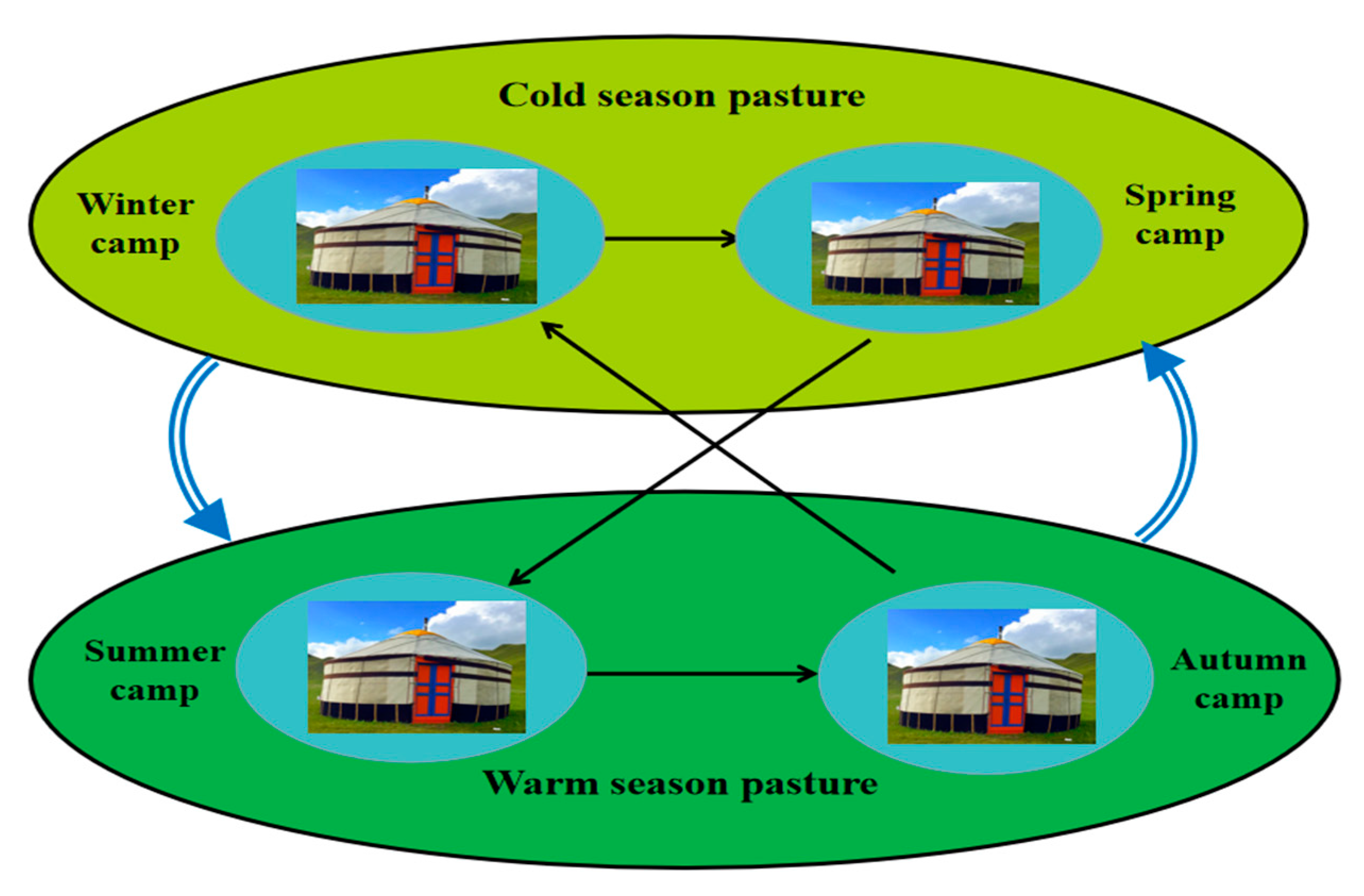

3.2.1. Influence on Livestock Grazing Form

- Grazing forms

- Grazing management

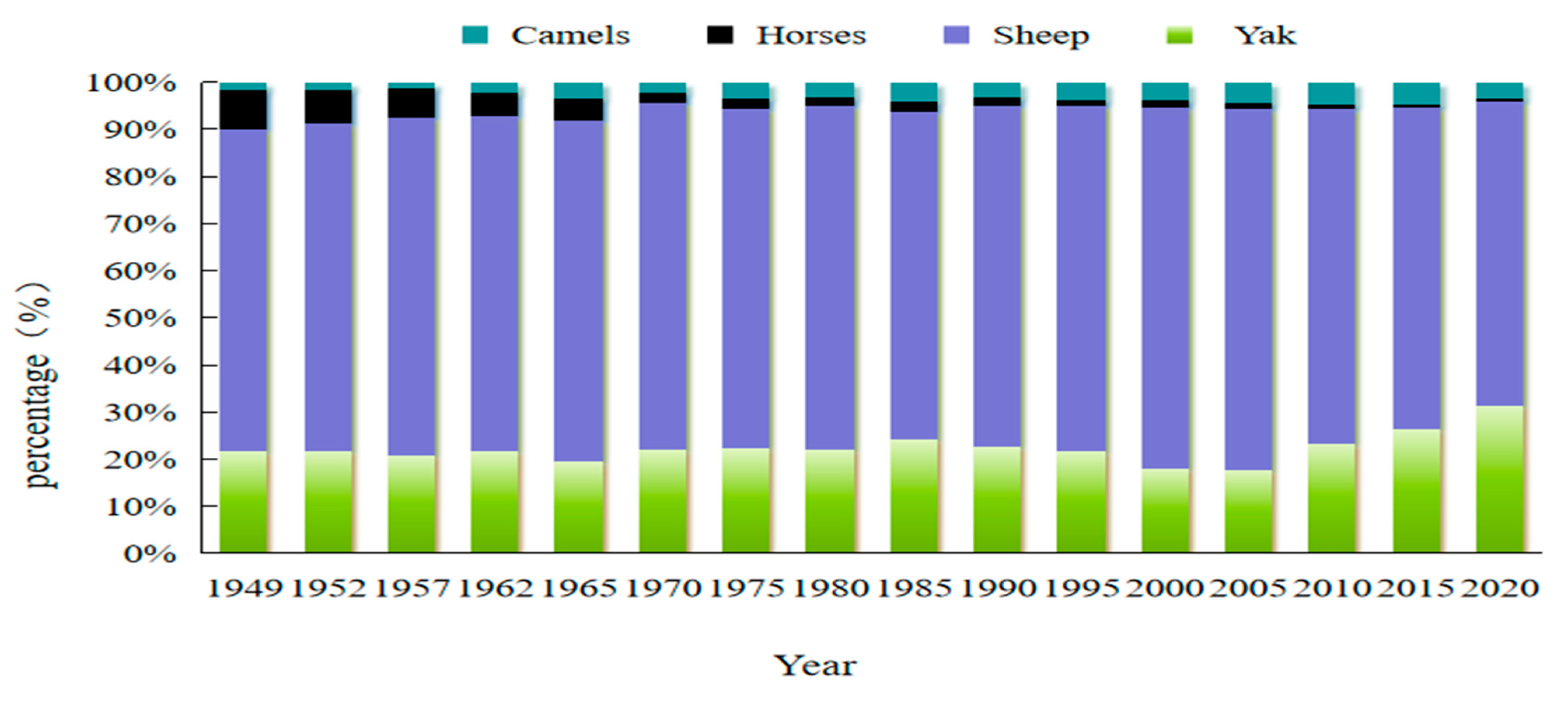

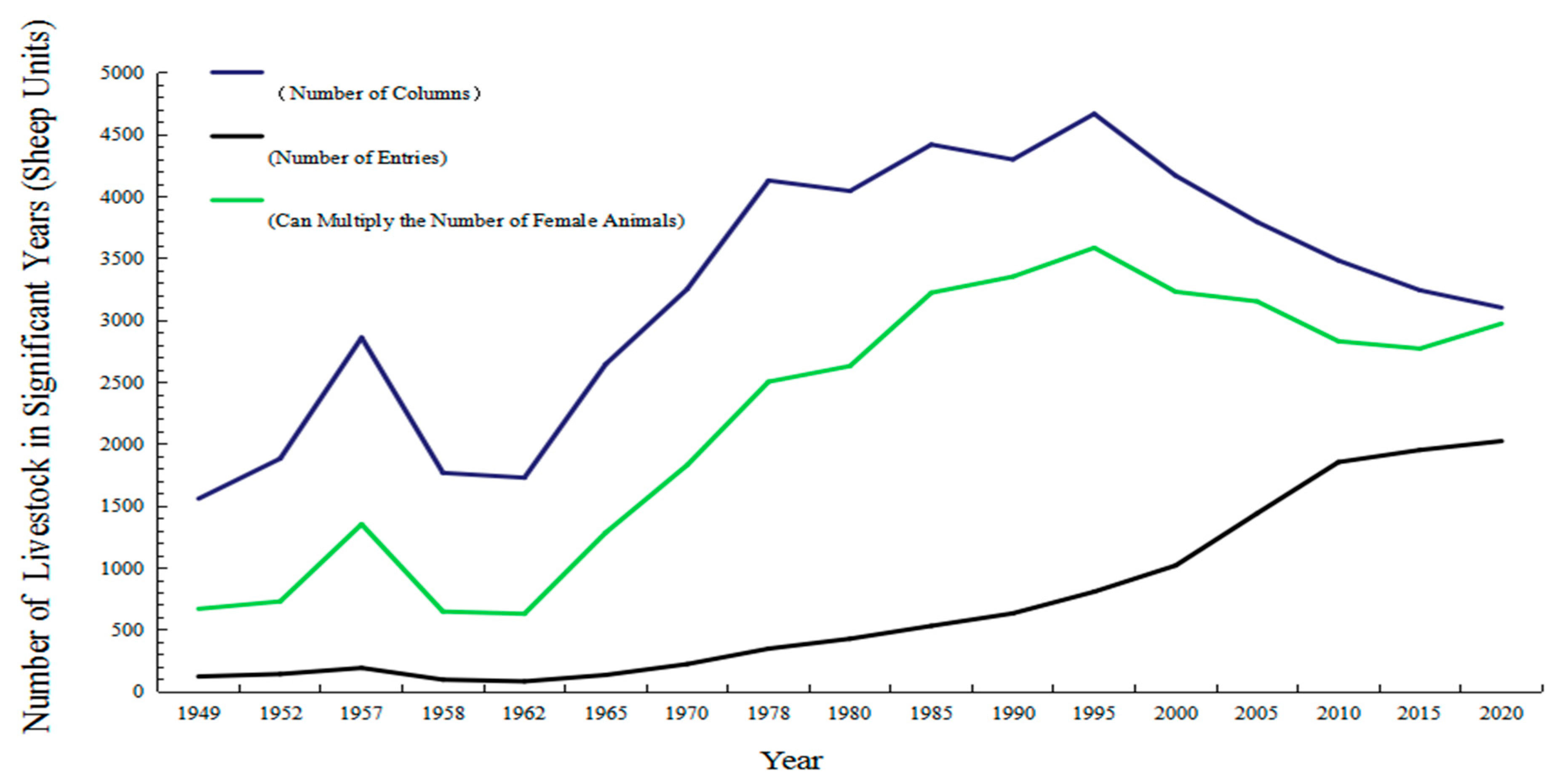

3.2.2. Impact on Herd Structure

- Changes in main livestock composition

- Proportion of main livestock and breeding capacity of female stock

3.2.3. Impact on Animal Husbandry Production

- Changes in natural grassland vegetation

- Construction of artificial grassland

- Changes in livestock breeding methods

3.3. The Influence of Property Rights Systems on Social Life in Pastoral Areas

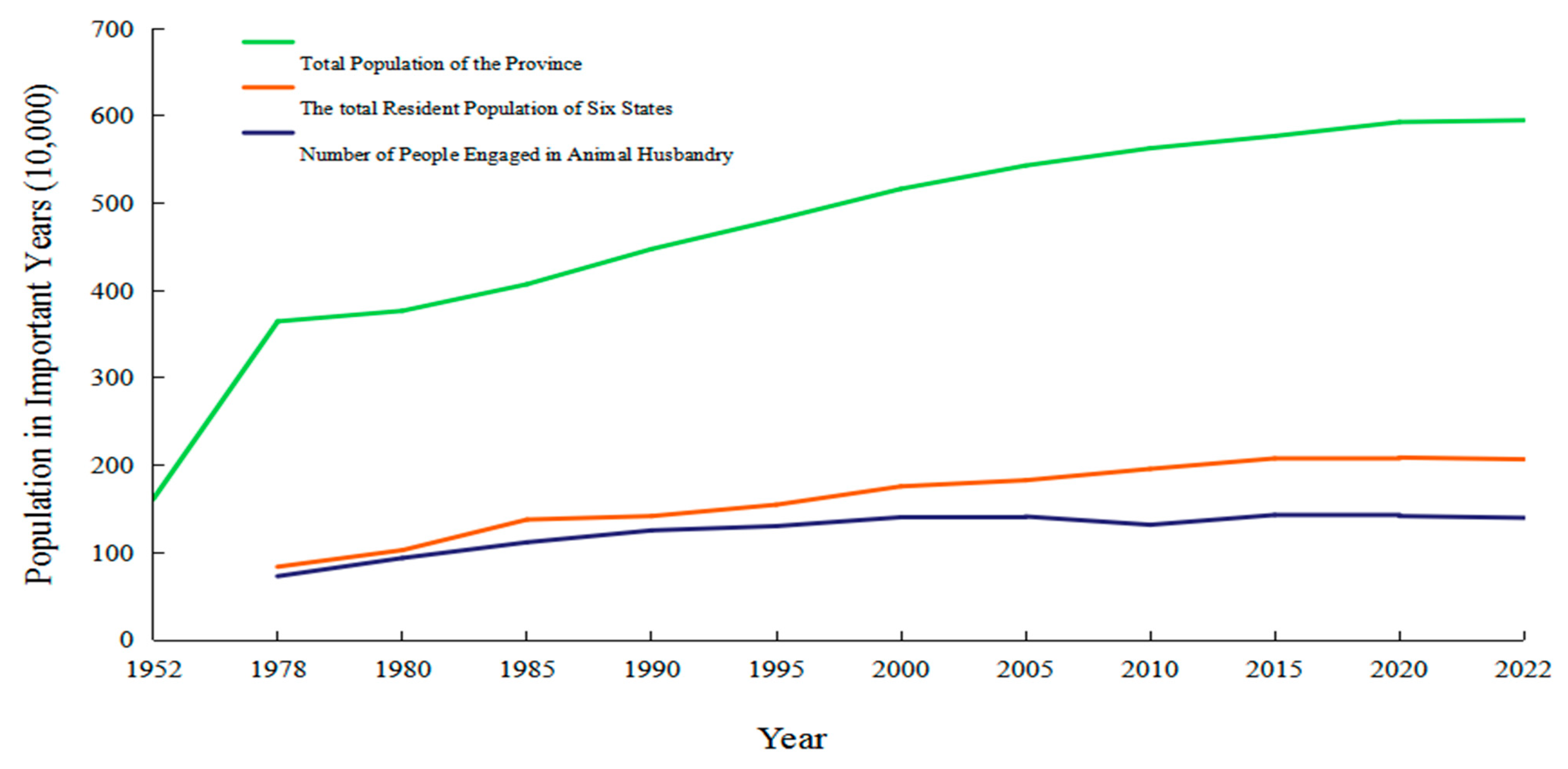

3.3.1. Impact on the Population Engaged in Animal Husbandry

- Proportion of the population engaged in animal husbandry

- Division of labor

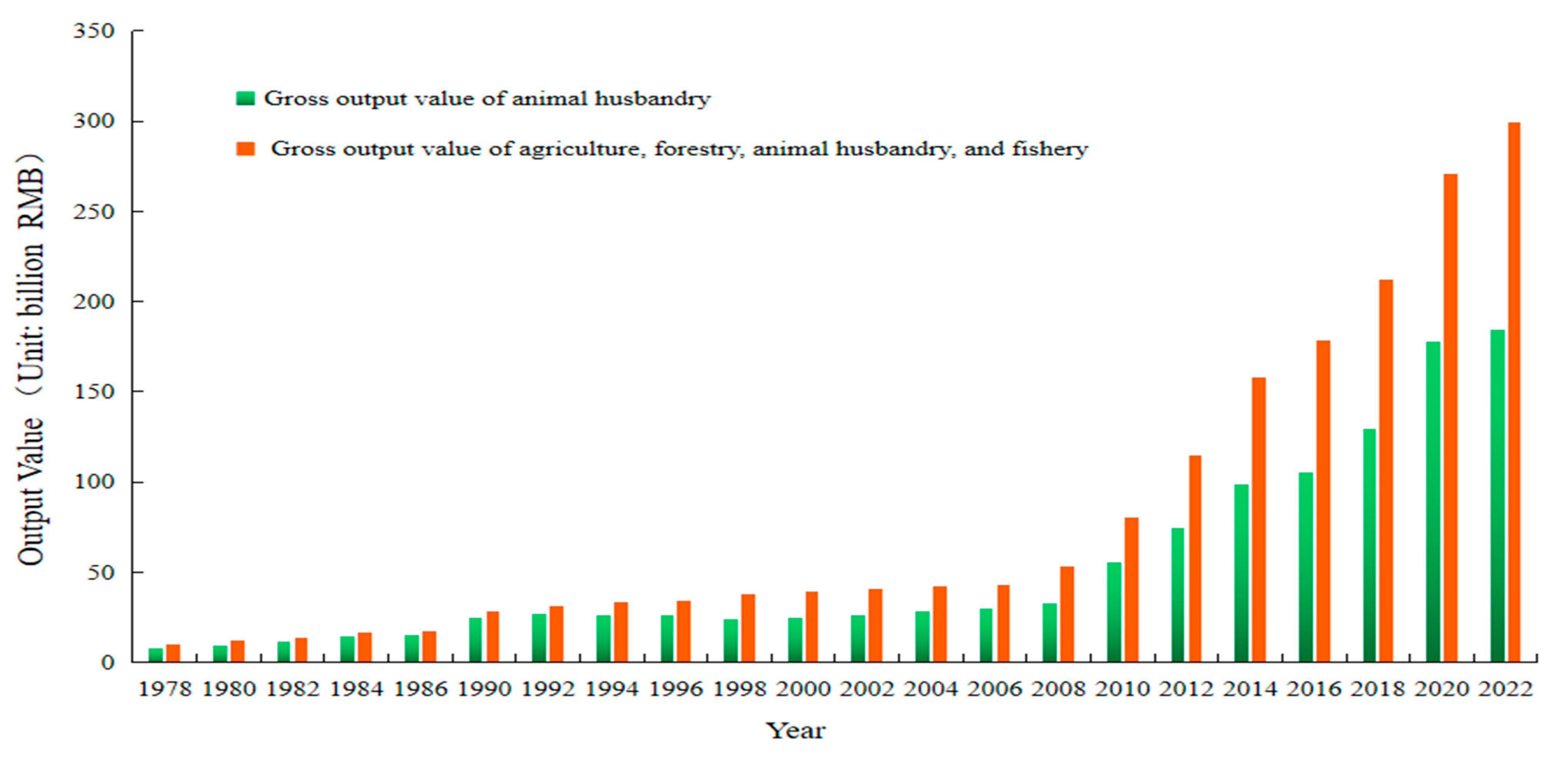

3.3.2. The Impact on the Output Value of Animal Husbandry

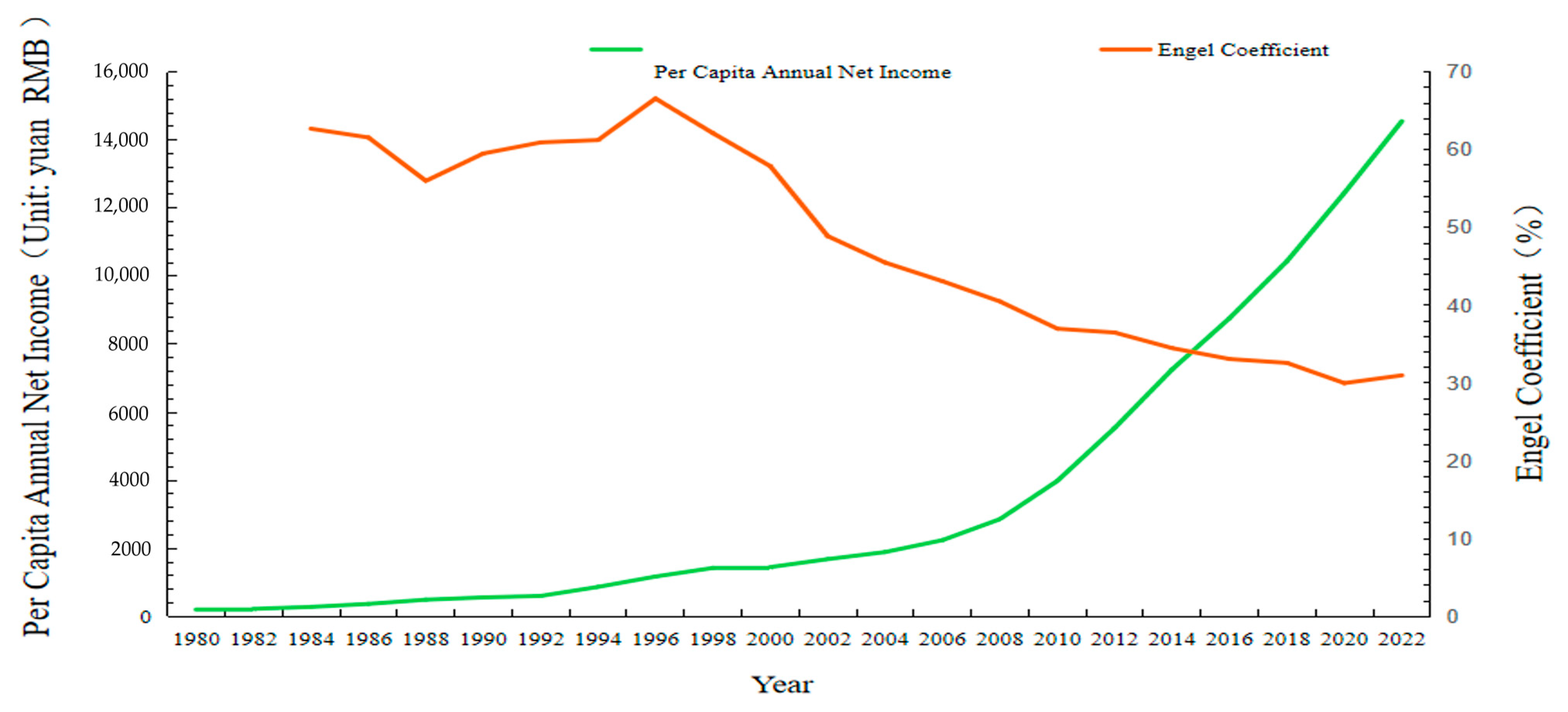

3.3.3. The Impact on the Life of Herdsmen

- The change in the humanistic environment of herdsmen’s life

- Changes in herdsmen’s income

- The change in income composition of herdsmen

4. Conclusions

5. Suggestions

5.1. Optimize the “Three-Rights Separation” Management Model to Lay a Solid Foundation for Property Rights System Reform

5.2. Improve the Guarantee Mechanism for the Reform of the Property Rights System and Form a New Pattern of Integrated Development of Industrial Management Entities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- MEA. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Desertification Synthesis; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, L.M.; Squires, V.R. Managing China’s pastoral lands: Current problems and future prospects. Land Use Policy 2015, 43, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Yang, M.; Ren, J.; Shang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Dong, Q.; Liu, W.; Ren, Q.; Dou, S.; Zhou, X. Sustainable grassland management based on grazing system unit: Concept and model. Pratacultural Sci. 2020, 37, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yang, C.; Meng, Z. Current situation, existing problems and suggestions of grassland ecological protection in China. Pratacultural Sci. 2016, 33, 1901–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Study on Ecological Poverty Reduction Effect of Herdsmen Grassland Turnover; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, J. Pathways for reintegration of fragmented grasslands. Man Biosph. 2021, 1, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B. Institutional Changes of Grassland Use and Management in the Process of Marketization on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau; Southwestern University of Finance and Economics Press: Chengdu, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council. Several Opinions on Strengthening the protection and restoration of grassland. Anim. Husb. Ind. 2021, 6, 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y. Research on Economic Effect of Grassland Transfer; Inner Mongolia University: Hohhot, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, G.; Yang, D.; Tang, Z. Analysis of Influencing factors of grassland transfer behavior of herdsmen on the Tibetan Plateau, based on a survey of 495 herdsmen. Chin. J. Grassl. Sci. 2019, 41, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, Z. On the Tribal Life of Tribes and Herdsmen in Modern Tibetan pastoral Areas. J. Liaoning Norm. Coll. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 2, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, M.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S. Research status and prospect of the impact of energy marketing on the local environment and human health in the pastoral group of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 43, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Yan, F.; Lu, Q. Spatiotemporal variation of vegetation on the Qinghai-Tibet plateau and the influence of climatic factors and human activities on vegetation trend (2000–2019). Remote Sensing. 2020, 12, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Fang, J.; Zhu, L.; Qu, J.; Han, F. Research on the construction of ecological compensation mechanism for grassland in pastoral areas in China. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2019, 41, 202–220. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Li, X.; Hou, F. Research progress and trends of grassland agroecology. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2002, 13, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Nan, Z.; Hao, D. Interface theory in pratacultural system. J. Pratacultural Ind. 2000, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Ma, S. Current situation and sustainable development of ecological animal husbandry in Tibetan areas of Qinghai Province. Contemp. Anim. Husb. 2019, 7, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. Research on Influencing Factors of Herdsmen’s Income from the Perspective of Cooperative Organizations-Based on a Survey in Yushu Prefecture; Southwest University of Finance and Economics: Chengdu, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B. Thoughts on accelerating the development of ecological animal husbandry in Qinghai Province. J. Climbing 2010, 1, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, S.; Li, M.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, J. Research progress on the causes of different grassland use patterns and their impacts on socio-ecosystem in the Tibetan Plateau. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 2149–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Analysis of influencing factors and countermeasures of ecological animal husbandry development in Qinghai Province. Resour. Environ. Qianearly Reg. 2019, 33, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Regional Culture and Regional Economic Development; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Study on Ecological Cognition and Grazing Behavior of Herdsmen in Northern China; Zhejiang University: Zhejiang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, X. Research on the reform of China’s rural collective property system under the background of new urbanization. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 10, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Ma, C.; Hou, X. Effects of livelihood strategies of herders on the transfer of contracted management rights of grassland. Resour. Environ. Ganchao Dist. 2019, 33, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Migulzab. The Development of Nomadic Animal Husbandry in the World; Ulaanbaatar Publishing House: Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, R.; Shi, Y. A comparative analysis of property rights system and grazing patterns of grassland in China and Mongolia. China Mongoliology 2008, 6, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jula, K. Research on Animal Husbandry Insurance in Mongolia; Inner Mongolia Agricultural University: Hohhot, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Melasu, U.T. Difficulties and Differences of animal husbandry in Mongolia since the transition of economic system. J. Inn. Mong. Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 6, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, T.P. Rights Reform in Rangeland China, Dilemma son the Road to the Household Ranch. World Dev. 2003, 31, 2129–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.H.B. Rangeland as a Common Property Resource, Contrasting Insights from Communal Areas of Central Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Hum. Ecol. 2007, 35, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Hou, X.; Yin, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, D. Are herders overloaded under the grassland subsidy policy? Who is overloading and its influencing factors, A case study of Inner Mongolia. J. Grassl. Sci. 2019, 28, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. 30 years of reform and development of grassland industry and animal husbandry in pastoral areas. Pratacultural Sci. 2009, 26, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, B.; Sun, D. The boundary and operation logic of “Relational Property Rights”—A Case study of Anhui L Farmer Cooperative Association. Chin. Rural Econ. 2018, 10, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Yang, H. The contradiction between the functions of the contract management system of grassland and the legal right structure of the “separation of three rights” in grassland. China Rural Obs. 2019, 1, 98–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Zhou, X. The historical evolution and future trend of the openness of rural collective property structure. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2019, 40, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. The inescapable “group”, Unit selection of China’s rural collective property reform, Based on the investigation of the rural collective property system reform pilot. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 47, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H. New institutional economic interpretation of ecological degradation in Sanjiangyuan area. Tibet Stud. 2007, 3, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Brockington, D.; Dyson, J.; Vira, B. Managing Tragedies, Understanding Conflictover Common Pool Resources. Science 2003, 302, 1915–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S. Impact of livestock system change on grassland degradation and its path. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 2, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Liu, M. Research on the Reform of land property right System and the development of Animal Husbandry Producties—A case study of land property Right reform in Inner Mongolia. Econ. Forum 2012, 5, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. Research on Economic Development of Southern Tibetan Areas in Qingnan; Qinghai Normal University: Qinghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. Research on Sustainable Economic and Social Development of Tibetan Areas in Qinghai; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y. Economic History of Qinghai (Ancient Volume); Qinghai People’s Publishing House: Xining, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. Research on grass rights system reform based on market economy. Issues Agric. Econ. 2011, 10, 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dan Zheng, C.D. Time limit system of pasture possession, A study on the new change of pasture property right system in a pastoral village in eastern Qinghai. Qinghai Ethn. Stud. 2019, 35, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M. Ecological migration Project and Mongolian cultural change. Inn. Mong. Sci. Technol. Econ. 2008, 11, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Gai, Z. Effect of grassland culture construction on sustainable development of grassland ecosystem. J. Grassl. Sci. 2008, 4, 765–786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B. Discussion on the development of animal husbandry in Qinghai during the Republic of China. Anc. Mod. Agric. 2011, 30, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S.; Cui, Y. Economic History of Qinghai (Contemporary Volume); Qinghai People’s Publishing House: Xining, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, P.Q.; Yao, Y.F. Reform of rural collective property rights system and Sustainable Development, from the perspective of New endogenous development theory. J. Agric. For. Econ. Manag. 2022, 5, 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Evolution of economic development path and strategic choice in the new era in western minority areas. Ethnic Forum. 2016, 5, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H. Economic stability and economic development in Tibetan Areas of China. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 12, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Du, M. Strategic transformation and implementation Strategy of economic development in Tibetan areas in China, a case study of Ganzi Tibetan Area. Econ. Res. 2017, 1, 123–124. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, S. Economic History of Qinghai (Modern Volume); Qinghai People’s Publishing House: Xining, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, J.S. Research on Reform of Collective Property Rights System in Agricultural and Pastoral Areas of Qinghai Province; Qinghai University: Xining, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. Realistic demands and path thinking on deepening rural property rights system reform under the new normal. Agric. Econ. 2024, 10, 107–109. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, L. Research on the Development Strategy of County Economy in China’s Minority Areas; Minzu University of China: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, F. On environmental justice in grassland ownership system. Pratacultural Sci. 2015, 32, 635–639. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Long, R.; Deng, B.; Zhang, M. Comparative analysis of grassland ecological outlook of herdsmen in three banners of Alxa League, Inner Mongolia. Acta Grassl. Sin. 2009, 17, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. Institutional Performance Analysis of Household Contract Responsibility System; Southwest Jiaotong University: Chengdu, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zu, K.; Luo, A.; Shresthan, N.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X. Altitudinal biodiversity patterns of seed plants along Gongga Mountain in the southeastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Evolution 2019, 9, 9586–9596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Tang, J.; Qiu, H. The effect of grassland transfer on herders’ livestock production and grazing intensity in Inner Mongolia and Gansu, China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. Ahead-Print 2021, 14, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, S. Performance evaluation of ecological animal Husbandry cooperatives, an empirical analysis of 55 ecological animal husbandry cooperatives in Tibetan areas of Qinghai Province. J. Qinghai Univ. Natl. 2014, 1, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Shao, K. The Development and Reform of China’s Farmer Cooperative Economic Organizations Under the New Situation, Summary of the International Symposium on “30 Years of Rural Reform in China, the Development of China’s Farmer Cooperative Economic Organizations”. Chin. Rural Econ. 2009, 1, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Chen, L.; Sun, Y. How to make the “three rights separation” of agricultural land more effective in the context of modern agricultural development, a study on the constraints and organizational governance based on the subdivision of property rights structure. Issues Agric. Econ. 2016, 37, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Ze, B.; Zhang, X. On the construction of ecological civilization in the Tibetan Plateau grassland. Rural Econ. 2015, 7, 106–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. Research on Tibetan Tribal System; China Tibetology Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. Study on the Transfer of Pasture and Its Impact on the Sustainability of Animal Husbandry; Northwest A&F University: Xianyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Zhao, M. Relationship network, social interaction and Herders’ pasture transfer behavior, a re-examination of the role of social capital in the transition period of pasture transfer market. J. Agric. Tech. Econ. 2023, 1, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.J. Research on Promoting the construction of modern agricultural management system under the background of “separation of three rights”. J. Agric. Econ. 2023, 8, 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Qinghai Bureau of Statistics. Qinghai Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Propaganda Department of Qinghai Provincial Committee. History of Animal Husbandry Economy in Qinghai; Qinghai Xinhua Printing Plant: Xining, China, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Ding, Z. Investigation and suggestions on the development of ecological animal husbandry cooperatives in Qinghai pastoral area. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F. Research on Grassland Property Rights Reform and Pastoral Area Governance, A Case Study of M Village, S Township, Xiahe County, Gansu Province; Central China Normal University: Wuhan, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, W. Effects of Grassland Subsidy Policy on Herders’ Satisfaction, Overloading Behavior and Livestock Reduction Decision-Making, A Case Study of Inner Mongolia; Lanzhou University: Lanzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.X.; de Jong, R.; Schmid, B.; Wulf, H.; Schaepman, M.E. Changes in grassland cover and in its spatial heterogeneity indicate degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 119, 106641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.L.; Fang, J.Y.; He, J.S. Variations in vegetation net primary production in the Qinghai-Xizang plateau, China, from 1982 to 1999. Clim. Change 2006, 74, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, W.; Zhou, C.; Ding, M.; Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Bai, W.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, D. Spatial and temporal variability in the nel primary production of alpine grassland on the Tibetan Plateau since 1982. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Liang, P.; Li, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, T.; Pan, K.; Liu, C. Trends in climate change and human interventions indicate grassland productivity on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau from 1980 to 2015. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 1008010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Ding, Q.; Meng, B.P.; Lv, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Yi, S. The relative contributions of climate and grazing on the dynamics of grassland NPP and PUE on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Kang, H.; Han, X.; Wang, Y. Spatial-temporal variation of grass yield in the source region of three Rivers from 2006 to 2015 based on MODIS NPP. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 1857–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ma, L.; Meng, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H. Effects of artificial grassland succession on forage quality in alpine region. Acta Grassl. Sin. 2023, 31, 2155–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Luo, F.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, J.; He, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Vegetation and soil characteristics of degraded alpine meadow during grazing recovery in warm season. J. Grassl. Sci. 2022, 1, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, L.; Li, D.; An, Y. Relationship between species diversity, functional composition and forage quality in typical alpine steppe of Qilian Mountains. Pratacultural Sci. 2012, 39, 1513–1520. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Chen, D.; Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Huo, L.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, X. Temporal and spatial distribution of herbage nutrition in alpine grassland of Sanjiangyuan. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 6304–6313. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zhou, B.; Song, M.; Qiao, A.; Wang, F.; Yu, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Ecological restoration of degraded grassland in Qinghai-Tibet alpine region: Degradation status, restoration measures, effects and prospects. Eff. Prospect. 2019, 39, 7441–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wu, S. Problems and sustainable development of prataculture in western alpine region. J. Pratacultural Sci. 2002, 11, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Sold, Y. Study on seasonal fluctuation of yak weight. Chin. Yak 1982, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, B. Study on the Appropriate Energy Level of Fattening and Meat Quality Control Diets for Growing Yaks; Qinghai University: Xining, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Hao, L.; Liu, S. Evaluation of forage nutrition value in different months of natural grazing in alpine meadow. Chin. J. Anim. Husb. Vet. Med. 2019, 47, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, J.; Hao, L.; Liu, S.; Chai, S.; Niu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Duoji, O. Evaluation of nutritional value of herbage in different phenological periods of alpine meadow in Zeku County, Qinghai Province by in vitro method. Chin. J. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 32, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. Research on property rights System reform of rural collective economic organizations under the background of rural revitalization. Agric. Econ. 2024, 21, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. Impact of pastoral household’s security cognition regarding grassland contracting rights on grassland transfer behavior: On the policy background of “extending the second round of land contracting for another 30 years after expiration”. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 38, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, C.; Long, R. Women’s social status and their awareness of grassland policy in Qilian Mountain grazing area. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 3472–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Research on Ecological Economy Development of Grassland in Qinghai Pastoral Area; Minzu University of China: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Analysis of economic environment and human environment of information construction in Qinghai. Qinghai Soc. Sci. 2007, 6, 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Analysis on the role of village rules and people’s conventions in the construction of rural style civilization. China Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 44, 202–226. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. Research on the Performance of Farmers’ Specialized Cooperatives; Sichuan Agricultural University: Ya’an, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, H. 2006–2007, Analysis and Forecast of Economic and Social Situation in Qinghai Province; Qinghai People’s Publishing House: Xining, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zaraga. Study on Collective Action Dilemma of Herdsmen Participating in Grassland Ecological Management; Tianjin University: Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Ownership | Right of Use | Grazing Range | Grazing Arrangements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clan tribe | Ruling class | Distributed by feudal lords | Fixed in a certain area for a period of time | Large-scale nomadic |

| Mutual Assistance and Cooperation | Country/Herdsman | Herdsman | Demarcated administrative areas | Rotational grazing by season |

| People’s Commune | Nation/Collective | Production team | Township/Town | Rotational grazing by season |

| Household Contract | Nation | Farm household | Contracted pasture | Rotational grazing on owned pastures |

| Ecological Animal Husbandry Cooperative | Nation | Farm household | Integrated available pasture | Rotational grazing by season |

| Data (Period) | Result | References |

|---|---|---|

| GIMMS (1982–1999) | The period from 1990 to 1991 witnessed a sharp decline, with no significant trend from 1982 to 1990. From 1991 to 1999, there was a significant increase of 7 × 109 g C per year. | Piao et al. [78] |

| GIMMS (1982–2000) SPOT (1998–2009) | NPP fluctuated and increased by 13.3%, NPP increased significantly in 32.56% of alpine grassland, and NPP decreased significantly in 5.55% of grassland. | Zhang et al. [79] |

| GIMMS (1980–2015) | The grasslands area increased at the rate of 1.08 g Cm-2a-1, and 75.13% of the grasslands area was significantly improved, with a slight negative trend in the northwest grasslands. | Xiong et al. [80] |

| MODIS (2000–2017) | Increased at a rate of 0.61 g Cm-2a-1, NPP increased significantly in 31.34% and decreased significantly in 0.68% of grasslands. | Yu et al. [81] |

| MODIS (2006–2015) | The overall grass yield (total) showed an upward trend, peaking in 2013 at close to 4000 × 104t, and slightly began to decline in 2014. The total grass yield in other years remained at about 2800 × 104t. | Lv et al. [82] |

| Period | Farming Methods |

|---|---|

| Clan tribe | Mainly free-range nomadic. |

| Mutual Assistance and Cooperation | Most herders began weeding ahead of time to reserve forage for their livestock to overwinter. |

| People’s Commune | Mowing, buying fodder for the winter, herdsmen began to feed moderately in the cold season. |

| Household Contract | Mowing, buying winter concentrate feed, good conditions of the family for warm season nutrition supplement. |

| Ecological Animal Husbandry Cooperative | Planting grass, mowing grass, buying winter concentrate feed, warm season nutrition supplement, etc. |

| Period | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Clan tribe | Young men take on tasks such as herding and hunting. | Young women cook, milk, and take care of the family. |

| Mutual Assistance and Cooperation | Men in the labor force are involved in livestock production. | Women in the labor force are engaged in milking, making livestock products, etc. |

| People’s Commune | Men are mainly responsible for most of the labor, such as animal husbandry production, installing fences, and planting. | Women assisted men in livestock production and took care of the family. |

| Household Contract and animal husbandry cooperatives | Men are responsible for the operation of cooperatives, overall planning of livestock production, and do most of the livestock labor. | Women assisted men in livestock production and took care of the family. |

| Age Group | Education | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illiteracy | Primary School | Junior School | Senior School and Above | |

| 8 to 20 years old | 0.00% | 1.19% | 5.32% | 19.13% |

| 21 to 30 years old | 0.06% | 2.26% | 14.09% | 19.45% |

| 31 to 40 years old | 1.19% | 3.19% | 3.26% | 1.01% |

| 41 to 50 years old | 2.26% | 13.96% | 1.06% | 0.06% |

| Over 51 years old | 8.28% | 3.10% | 1.13% | 0.00% |

| Total | 11.79% | 23.70% | 24.86% | 39.65% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gou, Y.; Hao, L.; Huang, Y.; Jin, X.; Zhang, A.; Ma, H. The Changes in Grassland Animal Husbandry and Herdsmen’s Life in the Qinghai Pastoral Area of China Based on the Perspective of Changes in the Grassland Property Rights System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031262

Gou Y, Hao L, Huang Y, Jin X, Zhang A, Ma H. The Changes in Grassland Animal Husbandry and Herdsmen’s Life in the Qinghai Pastoral Area of China Based on the Perspective of Changes in the Grassland Property Rights System. Sustainability. 2025; 17(3):1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031262

Chicago/Turabian StyleGou, Yujiao, Lizhuang Hao, Yayu Huang, Xinyan Jin, Airu Zhang, and Hongbo Ma. 2025. "The Changes in Grassland Animal Husbandry and Herdsmen’s Life in the Qinghai Pastoral Area of China Based on the Perspective of Changes in the Grassland Property Rights System" Sustainability 17, no. 3: 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031262

APA StyleGou, Y., Hao, L., Huang, Y., Jin, X., Zhang, A., & Ma, H. (2025). The Changes in Grassland Animal Husbandry and Herdsmen’s Life in the Qinghai Pastoral Area of China Based on the Perspective of Changes in the Grassland Property Rights System. Sustainability, 17(3), 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17031262