A Review of Mycelium-Based Composites in Architectural and Design Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To systematically identify the primary application fields of mycelium-based materials and determine the contexts (e.g., structural, insulating, esthetic) in which the material is currently employed.

- To identify the crucial functional properties (e.g., density, compressive strength, fire resistance) required for the material in specific application areas, correlating these needs with the type of mycelium strain and substrate utilized in the studied projects.

- To determine the dominant combinations of mycelium species and substrate types used in relation to a given application area.

- To discern and characterize the emerging trends in mycelium applications within the fields of architecture and design.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

- Quantitative analysis: the statistical compilation and visualization of all project data to quantify distribution patterns (e.g., the percentage distribution of fungal species, substrates, and applications over time).

- Qualitative analysis based on contextual thematic grouping and interpretive comparison of the quantified findings against established material science research and industry reports (e.g., justifying the preference for Ganoderma lucidum based on its documented mechanical properties, as discussed in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2).

2.2. The Selection Criteria

- Representing various applications in architecture, urban design, interior design, and art.

- Real-world projects only.

- Projects from 2007 to 2024, showcasing pioneering applications and more recent developments, indicating the evolution of mycelium-based solutions and the growing interest in their use.

- The analysis of each entry must document the fungal species and substrate composition, highlighting innovative approaches using agricultural byproducts and other organic materials.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data Summary

- Building materials: building blocks, bricks, self-supporting structures, and columns;

- Insulation and facade panels, used in building construction;

- Bioremediation.

- Furniture and lighting designs;

- Acoustic and decorative interior panels;

- Flooring;

- Upholstery and textiles;

- Coffins;

- Installations and sculptures of art;

- Packaging.

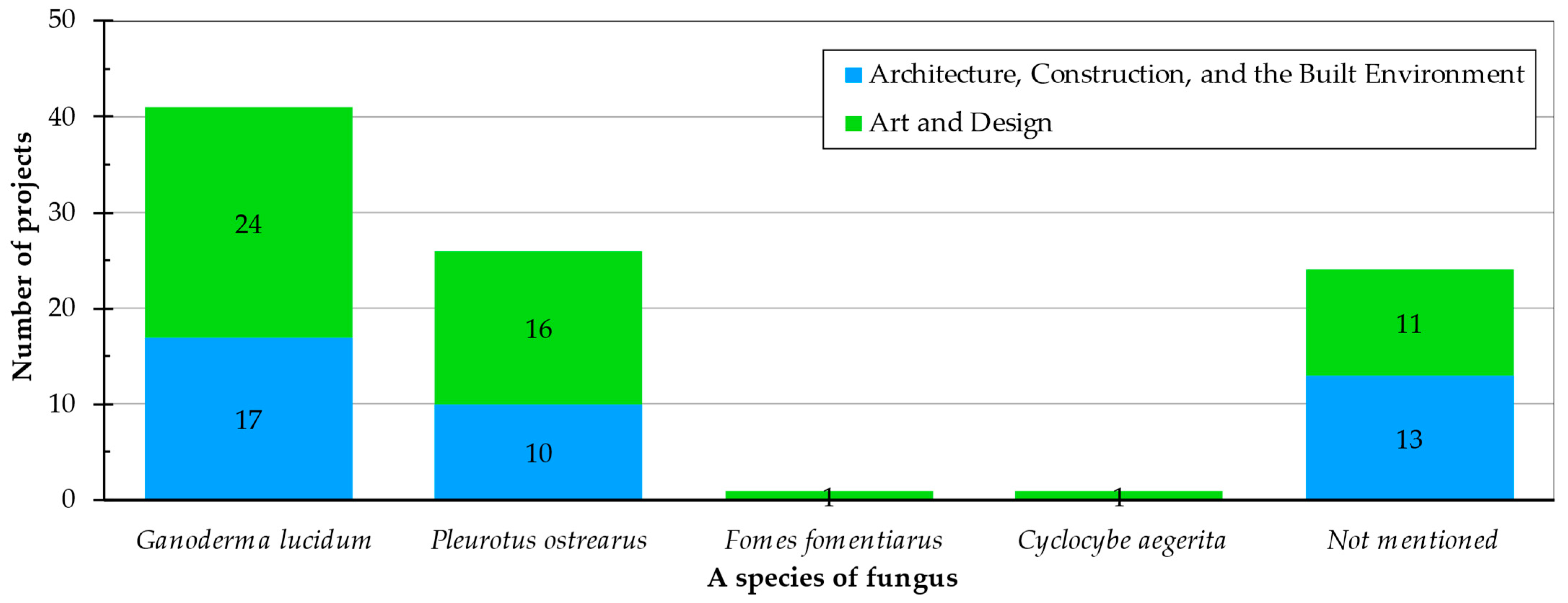

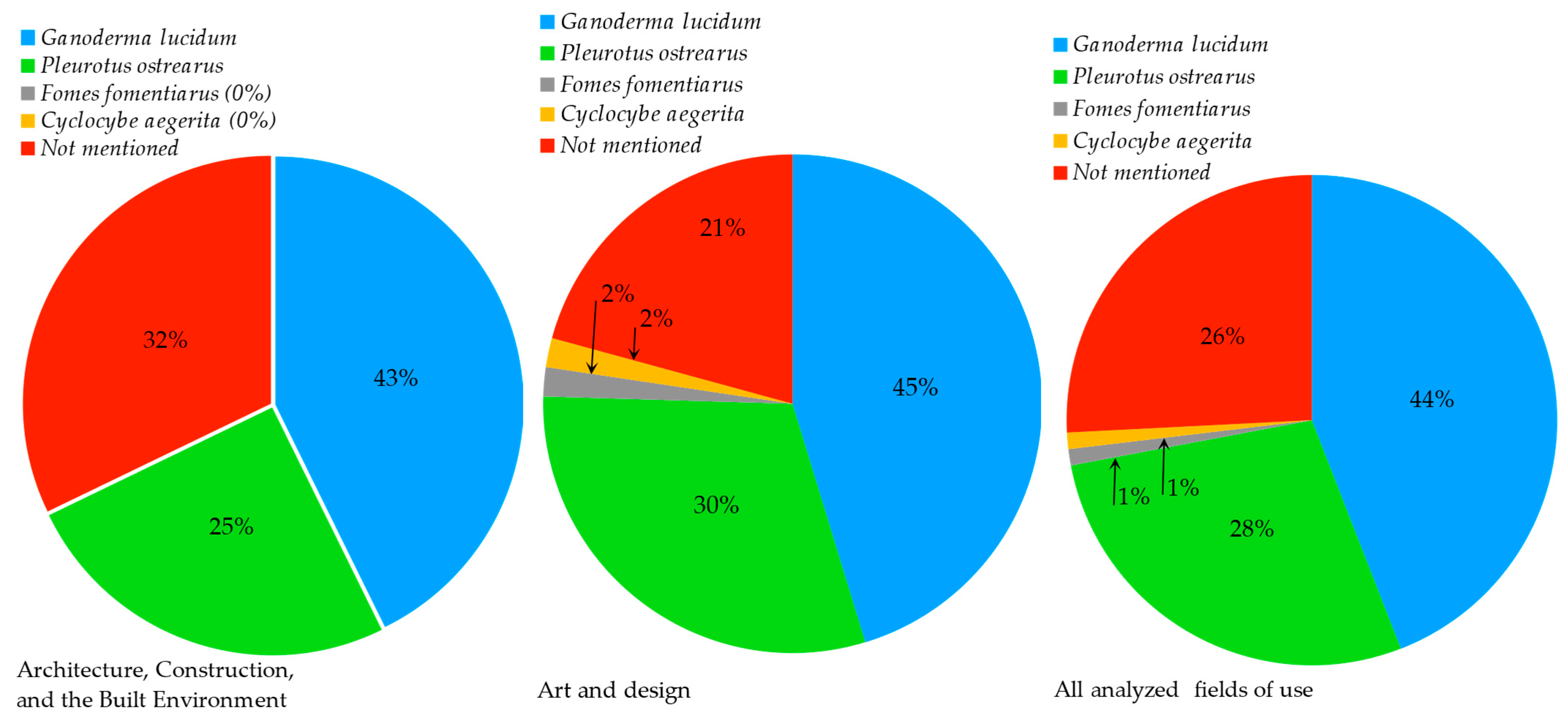

3.2. Mycelium Types

3.3. Substrates

3.4. Main Manufacturers

3.5. Trends and Prospects

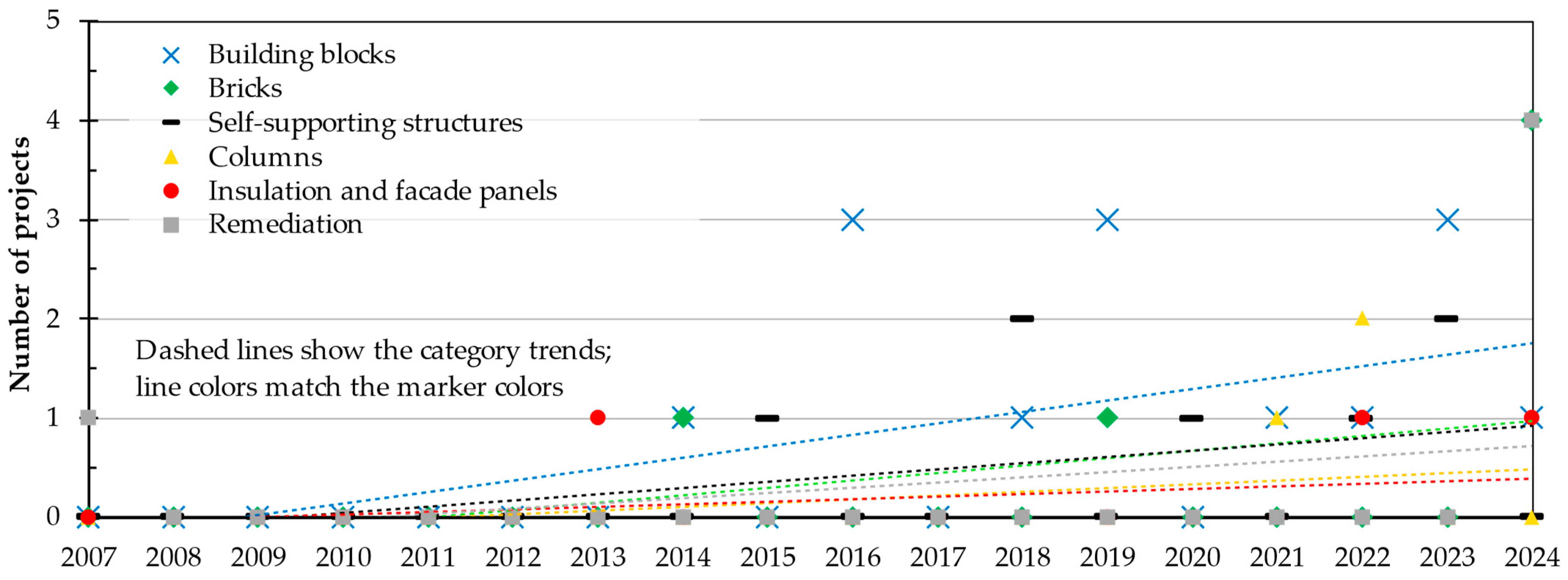

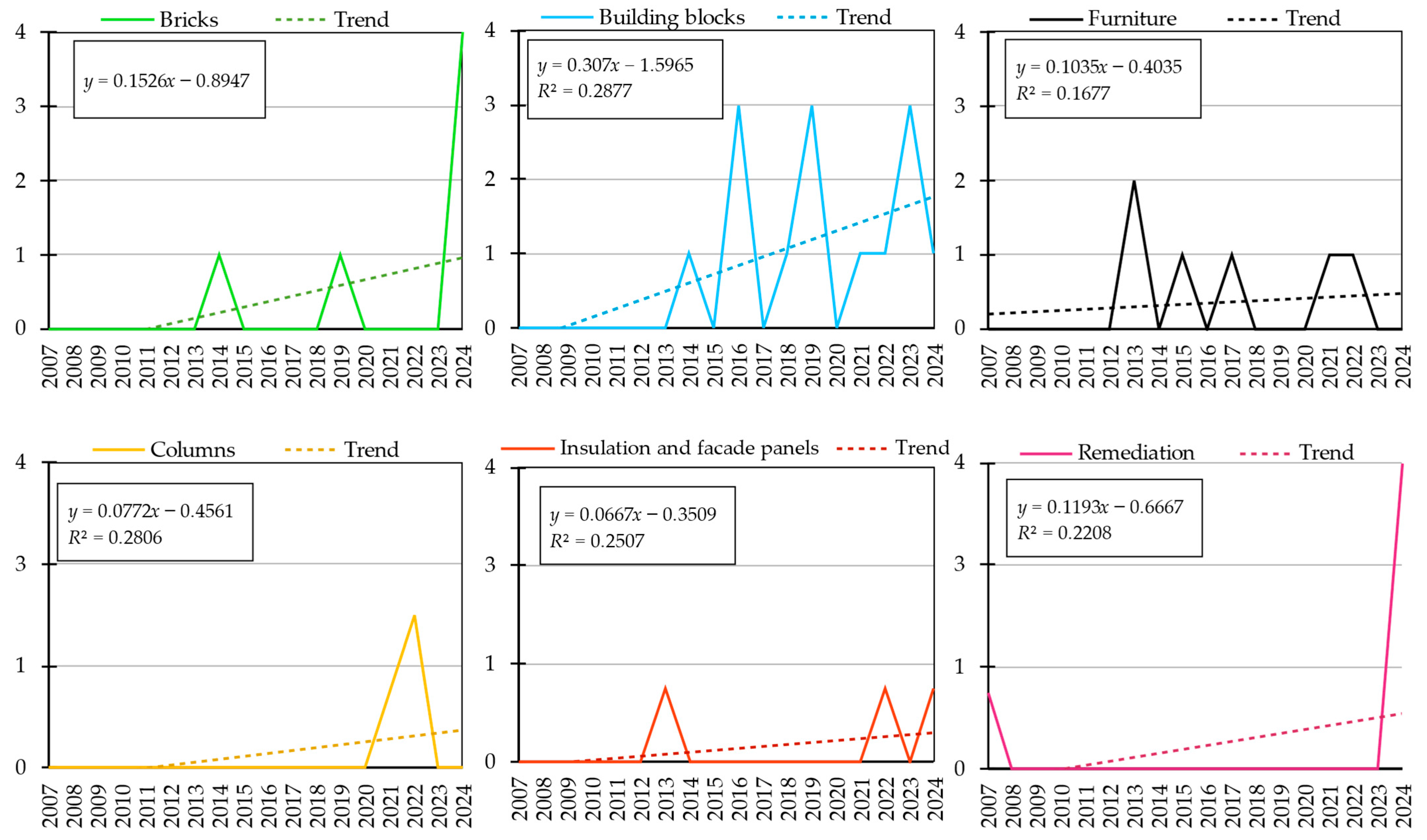

- Architecture, construction, and urban planning: Forty examples were analyzed. Next, the examples were divided into groups according to the type of mycelium application used in the project, as shown in Table 1. In the “Application” section, trends were examined across smaller subgroups.

- Design and art: An analysis was carried out on 50 examples, which were then further divided into groups according to the type of mycelium application used in the project, as shown in Table 1. In the “Application” section, trends were examined across smaller subgroups.

3.6. Extrapolation of the Trends and Possible Future Impacts

3.7. Study Limitations

4. Conclusions

- Architectural and technical applications primarily rely on Ganoderma lucidum and carefully selected lignocellulosic substrates (e.g., straw and wood/sawdust).

- Art and design projects show greater experimental diversity, frequently utilizing Pleurotus ostreatus and generalized agricultural waste for esthetic and conceptual purposes.

- Broadening the functional material palette by increasing the number of robust mycelium species utilized beyond the current two dominant strains.

- Developing protective treatments and processing techniques to significantly enhance mechanical strength, improve resistance to moisture uptake, and ensure long-term service life for applications requiring greater load-bearing capacity and outdoor exposure.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dyson, A.; Keena, N.; Lokko, M.; Reck, B.K.; Ciardullo, C. Building Materials and the Climate: Constructing a New Future; Technical Reports; United Nations Environment Programme, & Yale Center for Ecosystems + Architecture: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2022 Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Towards a Zero-Emission, Efficient and Resilient Buildings and Construction Sector; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; ISBN 978-92-807-3984-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sydor, M.; Bonenberg, A.; Doczekalska, B.; Cofta, G. Mycelium-Based Composites in Art, Architecture, and Interior Design: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Walczyk, D.; McIntyre, G.; Bucinell, R. A New Approach to Manufacturing Biocomposite Sandwich Structures: Mycelium-Based Cores. In Proceedings of the ASME 2016 11th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 27 June–1 July 2016; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2016; Volume 1, p. V001T02A025. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, G.A.; Mcintyre, G.; Flagg, D.; Bayer, E.; Wanjura, J.D.; Pelletier, M.G. Fungal Mycelium and Cotton Plant Materials in the Manufacture of Biodegradable Molded Packaging Material: Evaluation Study of Select Blends of Cotton Byproducts. J. Biobased Mat. Bioenergy 2012, 6, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attias, N.; Danai, O.; Abitbol, T.; Tarazi, E.; Ezov, N.; Pereman, I.; Grobman, Y.J. Mycelium Bio-Composites in Industrial Design and Architecture: Comparative Review and Experimental Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 246, 119037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimele, Z.; Irbe, I.; Grinins, J.; Bikovens, O.; Verovkins, A.; Bajare, D. Novel Mycelium-Based Biocomposites (MBB) as Building Materials. J. Renew. Mater. 2020, 8, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaneme, K.K.; Anaele, J.U.; Oke, T.M.; Kareem, S.A.; Adediran, M.; Ajibuwa, O.A.; Anabaranze, Y.O. Mycelium Based Composites: A Review of Their Bio-Fabrication Procedures, Material Properties and Potential for Green Building and Construction Applications. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 83, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerimi, K.; Akkaya, K.C.; Pohl, C.; Schmidt, B.; Neubauer, P. Fungi as Source for New Bio-Based Materials: A Patent Review. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, M.G.; Holt, G.A.; Wanjura, J.D.; Lara, A.J.; Tapia-Carillo, A.; McIntyre, G.; Bayer, E. An Evaluation Study of Pressure-Compressed Acoustic Absorbers Grown on Agricultural by-Products. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girometta, C.; Picco, A.M.; Baiguera, R.M.; Dondi, D.; Babbini, S.; Cartabia, M.; Pellegrini, M.; Savino, E. Physico-Mechanical and Thermodynamic Properties of Mycelium-Based Biocomposites: A Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Han, C.; Li, Y.; Price, E.; Wnek, G.; Liao, Y.-T.T.; Yu, X. (Bill) Novel Strategies to Grow Natural Fibers with Improved Thermal Stability and Fire Resistance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 320, 128729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandelook, S.; Elsacker, E.; Van Wylick, A.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Current State and Future Prospects of Pure Mycelium Materials. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiduang, W.; Jatuwong, K.; Jinanukul, P.; Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Thamjaree, W.; Teeraphantuvat, T.; Waroonkun, T.; Oranratmanee, R.; Lumyong, S. Sustainable Innovation: Fabrication and Characterization of Mycelium-Based Green Composites for Modern Interior Materials Using Agro-Industrial Wastes and Different Species of Fungi. Polymers 2024, 16, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.R.; Tudryn, G.; Bucinell, R.; Schadler, L.; Picu, R.C. Morphology and Mechanics of Fungal Mycelium. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amstislavski, P.; Pöhler, T.; Valtonen, A.; Wikström, L.; Harlin, A.; Salo, S.; Jetsu, P.; Szilvay, G.R. Low-Density, Water-Repellent, and Thermally Insulating Cellulose-Mycelium Foams. Cellulose 2024, 31, 8769–8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Vandelook, S.; Brancart, J.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mechanical, Physical and Chemical Characterisation of Mycelium-Based Composites with Different Types of Lignocellulosic Substrates. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livne, A.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Pearlmutter, D.; Gal, E. Fungal Mycelium Bio-Composite Acts as a CO2 -Sink Building Material with Low Embodied Energy. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12099–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Canale, C.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Athanassiou, A. Advanced Materials From Fungal Mycelium: Fabrication and Tuning of Physical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, F.V.W.; Camere, S.; Montalti, M.; Karana, E.; Jansen, K.M.B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Krijgsheld, P.; Wösten, H.A.B. Fabrication Factors Influencing Mechanical, Moisture- and Water-Related Properties of Mycelium-Based Composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 161, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Lee, K.-P. Unraveling the Sensorial Properties in Material Identity Innovation: A Study on Mycelium-Based Composite. In Proceedings of the DRS2024, Boston, MA, USA, 23–28 June 2024; Design Research Society: London, UK, 2024; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, K.; Dhiman, S.; Mukherjee, G. Embracing Microbial Systems in Built Environments Fostering Sustainable Development through Circular Economy Practices. In Waste to Wealth: Emerging Technologies for Sustainable Development; Dhiman, S., Mukherjee, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-1-040-45378-0. [Google Scholar]

- Heisel, F.; Schlesier, K.; Lee, J.; Rippmann, M.; Saeidi, N.; Javadian, A.; Hebel, D.E.; Block, P. Design of a Load-Bearing Mycelium Structure through Informed Structural Engineering. The MycoTree at the 2017 Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Sustainable Technologies (WCST-2017), Cambridge, UK, 11–14 December 2017; Infonomics Society: London, UK, 2017; pp. 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Beautiful World, Where Are You? Mc Carthy, S., Ed.; Art/Books: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-908970-44-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, P. Method for Producing Fungus Structures. Patent US 9410116 B2, 9 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, S.; Price, B.; Bourdon, P.; Gibby, P. The Hayes Pavilion 2023 6—An Investigation into Mycelium as an Alternative Material for the Creative Industries; Hayes Pavilion; Team Love and Temple Design Studio, in Association with Glastonbury Festival: Bristol, UK, 2023; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Ratti, C. A Living Architecture for the Digital Era. Diségno 2019, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despret, V.; Mahieu, F.; Dalon, C.; Aventin, C.; Salme, J. Demeurer en Mycélium/Living in Mycelium; Cellule Architecture de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelle: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; ISBN 978-2-930705-49-1. [Google Scholar]

- Meglio, C.D. MycoTemple. Available online: www.comedimeglio.com/copie-de-mycotemple-fr (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Rovers, I.; La Bianca, I.; Peuling, S.; Vette, J.; Ng-Caradt, W.; Pelkmans, J. Whitepaper: Building on Mycelium; Centre of Expertise Biobased Economy (CoE BBE): Breda, The Netherlands, 2022; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- MycoShell at BuildFest. Available online: https://labs.aap.cornell.edu/node/1127 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Rothschild, L.J.; Maurer, C.; Paulino Lima, I.G.; Senesky, D.; Wipat, A.; Head, J., III. Myco-Architecture of Planet: Growing Surface Structures at Destination. NIAC 2018 Phase I Final Report; NASA Ames Research Center: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2019; p. 57.

- Tupper, P. Welcome to Symbiocene Living! PLP Architecture International Ltd. 2023. Available online: https://plplabs.com/symbiocene/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Beneš, V. The Exhibition “Into the Depths of Fungi” Opens the Door. Inovace od Buřinky. 2023. Available online: www.inovaceodburinky.cz/en/the-exhibition-into-the-depths-of-fungi-open-the-door/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Crembil, G.; Lokko, M.-L.; Roland, T. Mycelium Pavilion [Summer Design & Build Studio]. Rensselaer Architecture. 2019. Available online: www.arch.rpi.edu/2019/09/2019su-summerstudio/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Material Atlas. The Growing Pavilion; van den Berg, J., Konings, B., Eds.; Company New Heroes: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/157rALVRRQzTuxdGf0MUf63IjbwVHWtD- (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Jones, M.; Mautner, A.; Luenco, S.; Bismarck, A.; John, S. Engineered Mycelium Composite Construction Materials from Fungal Biorefineries: A Critical Review. Mater. Des. 2020, 187, 108397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer Hahn Glastonbury’s Hayes Pavilion “Pushes the Boundaries” of What Bioplastic Can Do. Dezeen. 2024. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2024/06/27/glastonbury-hayes-pavilion-reright-design/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Wierzbicka, A.M.; Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M.; Ławińska, K.; Haupt, P.; Gubert, M.; Paoletti, G.; Lollini, R.; Kavka, U. Innovative Use of Mycelium in Construction. Sr. Mieszk. Hous. Environ. 2024, 49, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A. Homegrown Wonderland. Andre Kong Studio. 2024. Available online: www.andrekong.com/homegrown-wonderland.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Tupper, P. PLP Labs Showcase Mycelium Blocks at Edinburgh’s Fungi Forms. PLP Architecture. 2024. Available online: https://plparchitecture.com/plp-labs-showcase-mycelium-blocks-at-edinburghs-fungi-forms/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Jain, A.; Ardern, J. Mycotecture (Phil Ross). Design and Violence. 2014. Available online: https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2013/designandviolence/mycotecture-phil-ross/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Brayer, M.-A. Organic Design: Towards New Artefacts. PCA–STREAM. 2021. Available online: www.pca-stream.com/en/explore/organic-design-towards-new-artefacts/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Meyer, V.; Schmidt, B.; Pohl, C.; Schmidts, C.; Hoberg, F.; Weber, B.; Stelzer, L.; Angulo Meza, A.; Saalfrank, C.; Sharma, S.; et al. Engage with Fungi; Meyer, V., Pfeiffer, S., Eds.; Berlin Universities Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2022; ISBN 978-3-98781-001-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dessi-Olive, J. Monolithic Mycelium: Growing Vault Structures. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Non-Conventional Materials and Technologies—IC NOCMAT, IC-NOCMAT 2019, Nairobi, Kenya, 24–26 July 2019; pp. 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, A.; Vieira, F.R.; Pecchia, J.A.; Gürsoy, B. Three-Dimensional Printing of Living Mycelium-Based Composites: Material Compositions, Workflows, and Ways to Mitigate Contamination. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauk, J.; Gosch, L.; Vašatko, H.; Christian, I.; Klaus, A.; Stavric, M. MyCera. Application of Mycelial Growth within Digitally Manufactured Clay Structures. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 2022, 20, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.; Bridgens, B.; Elsacker, E.; Scott, J. BioKnit: Development of Mycelium Paste for Use with Permanent Textile Formwork. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1229693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Davidson, A.; Ravi, D.; Batmaz, D.; Do, D. Symbiocene Architecture: Building with Mycelium; Report; PLP Architecture: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- How Will We Live Together? Sarkis, H., Ed.; La Biennale di Venezia; La Biennale di Venezia in Collaboration with Silvana Editoriale: Venice, Italy, 2021; Volume 1, ISBN 978-88-366-4859-7. [Google Scholar]

- Robbie Jenkins Building Organic Sculptures Using Mycelium. Available online: https://www.myminifactory.com/stories/robbie-jenkins-building-organic-sculptures-using-mycelium (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Yang, K. Investigations of Mycelium as a Low-Carbon Building Material. Bachelor’s Thesis, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA, 2020. Available online: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/engs88/21 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Dias, P.P.; Jayasinghe, L.B.; Waldmann, D. Investigation of Mycelium-Miscanthus Composites as Building Insulation Material. Results Mater. 2021, 10, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattanavichean, N.; Phanthuwongpakdee, J.; Koedrith, P.; Laoratanakul, P.; Thaithatgoon, B.; Somrithipol, S.; Kwantong, P.; Nuankaew, S.; Pinruan, U.; Chuaseeharonnachai, C.; et al. Mycelium-Based Breakthroughs: Exploring Commercialization, Research, and Next-Gen Possibilities. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2025, 5, 3211–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noronha, M. Crema Lab. Furf Design Studio. 2024. Available online: http://furf.it (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Rodriguez, J. How It Works. Available online: https://mycocycle.com/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Shaw, M. What Is a Life Box and Who Is Paul Stamets, Anyway?—The Colorado Mycological Society. Available online: https://cmsweb.org/what-is-a-life-box-and-who-is-paul-stamets-anyway/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Stamets, P. The Petroleum Problem. Fungi Perfecti. 2010. Available online: https://fungi.com/blogs/articles/the-petroleum-problem?srsltid=AfmBOooM5CXcWF81qjmMm6HuC8KItL0xq6SyXu-0HSD0-z30HLwcusXw (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Khatua, S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Acharya, K. Myco-Remediation of Plastic Pollution: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. Biodegradation 2024, 35, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, A.; Mora, G.C. Mushroom Tech Cleans Up at Lake Erie State Park. New York State Parks and Historic Sites Blog. 2019. Available online: https://nystateparks.blog/2019/12/10/mushroom-tech-cleans-up-at-lake-erie-state-park/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Deniz, I.; Keskin Gundogdu, T. Biomimetic Design for a Bioengineered World. In Interdisciplinary Expansions in Engineering and Design with the Power of Biomimicry; Kokturk, G., Altun, T.D.A., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 57–75. ISBN 978-953-51-3936-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kieft, R. Waste as Resource. Mediamatic. 2014. Available online: www.mediamatic.net/nl/page/222463/waste-as-resource (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Frearson, A. Mushroom Mycelium Used to Create Suede-Like Furniture by Sebastian Cox and Ninela Ivanova. Dezeen. 2017. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2017/09/20/mushroom-mycelium-timber-suede-like-furniture-sebastian-cox-ninela-ivanova-london-design-festival/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Karana, E.; Blauwhoff, D.; Hultink, E.-J.; Camere, S. When the Material Grows: A Case Study on Designing (with) Mycelium-Based Materials. Int. J. Des. 2018, 12, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Totaro, A.I. Startup: Mycelium-Based Furniture and Packaging from RongoDesign Materia Rinnovabile. Renewable Matter. 2023. Available online: https://www.renewablematter.eu/en/Startup-Mycelium-based-Furniture-Packaging-from-RongoDesign-biomaterials (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Garnousset, P.; Detoeuf, M.; de Pingon, P. Tree Table/Endless Vase. Biobased Materials. 2022. Available online: https://biobasedmaterials.org/material/tree-table-endless-vase/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Edward Linacre Godlight and Toadstool: Mycelium Furniture and Lighting. Available online: https://www.edwardlinacre.com.au/light-/-object/nest-s7r92-4z6wb-zbpw4-3gf2t (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Van der Voorn, M.T. Conch Light. Marc Th. van der Voorn|Allround Furniture Designer 2023. Available online: https://marcvandervoorn.nl/category/lighting (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Saint, A. The Magic of Mushrooms for Sustainability [Sustainability Innovation]. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, N. Nir Meiri Makes Sustainable Lamp Shades from Mushroom Mycelium. Dezeen. 2019. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2019/01/07/nir-meiri-mycelium-lamps-design/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Those Light Fixtures Are Made out of Mushroom; Hogar line; Ola Luminárias Acústicas: Curitiba, Brasil, 2024; p. 12. Available online: https://ola-br.com/catalogos/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Montalti, M. Acoustic. Acoustic Mycelium-Based Products; Mogu: Inarzo, Italy, 2023; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft, T. FIKA Acoustic Wall Tiles by AllSfär | Dezeen Showroom. Dezeen. 2023. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2023/05/22/fika-allsfar-acoustic-wall-panel-mycelium-dezeen-showroom/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Astbury, J. Mycelium Insulates Experimental Timber Pavilion by Myceen and EKA PAKK. Dezeen. 2025. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2025/09/21/myceen-eka-pakk-pavilion-mycelium/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Osekowska, M. Fumo Panels. Mycelium Wall Panels. 2025. Available online: https://fumopanels.com/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Barta, G. Rongo Design. Available online: https://rongodesign.com/?elementor_library=coming-soon (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Yoneda, Y. Terreform ONE Unveils Mushroom Chair Grown out of Fungi in Just Seven Days Mycellium | Inhabitat-Green Design, Innovation, Architecture, Green Building. Inhabitat-Green Design, Innovation, Architecture, Green Building | Green Design & Innovation for a Better World 2016. Available online: https://inhabitat.com/terreform-one-unveils-mushroom-chair-grown-out-of-fungi-in-just-seven-days/terreform-one-unveils-mushroom-chair-grown-out-of-fungi-in-just-seven-days-mycellium/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Castenson, J. MycoBoard Offers an Innovative, Sustainable Solution for Building Products. Builder Magazine. 2017. Available online: www.builderonline.com/products/mycoboard-offers-an-innovative-sustainable-solution-for-building-products_o (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Gandia, A. Growing a Mycelium Panel. Available online: www.mediamatic.net/en/page/227540/growing-a-mycelium-panel (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Wösten, H. Fungal Futures. Officina Corpuscoli. 2014. Available online: www.corpuscoli.com/projects/fungal-futures/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Lempi, V. Bio-Based Industry: Is It Possible? Interni Magazine. 2023. Available online: www.internimagazine.com/features/industria-bio-based-si-puo/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Dorsch, E. Student Researcher Develops Building Materials from Mycelium. Available online: https://news.uoregon.edu/student-researcher-develops-building-materials-mycelium (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Melendez, F. bioMATTERS Crafts Tiling System by 3D Printing Mycelium, Algae, and Organic Waste. Designboom|Architecture & Design Magazine. 2023. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/design/biomatters-sustainable-tiling-system-3d-printing-mycelium-algae-myco-alga-11-06-2023/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Jarz, H. Re-Cell/Stanislaw Mlynski. Available online: www.archdaily.com/141008/re-cell-stanislaw-mlynski (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- McCandless, M. Appalachian Students Partner with Biomaterials Company, Build Sustainable Products. Available online: https://today.appstate.edu/2017/04/21/ecovative-design (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Michaeloudis, C. Orbit—Floor-Standing Screens. AllSfär. 2023. Available online: https://allsfar.com/product/orbit/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Williams, E.; Cenian, K.; Golsteijn, L.; Morris, B.; Scullin, M.L. Life Cycle Assessment of MycoWorks’ ReishiTM: The First Low-Carbon and Biodegradable Alternative Leather. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2022, 34, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, G. Profile of Bolt Threads: A Leader in Novel Biomaterials; Performance Apparel Markets; Textiles Intelligence: Cheshire, UK, 2021; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.; Dietrich, S.; Schulz, H.; Mondschein, A. Comparison of the Technical Performance of Leather, Artificial Leather, and Trendy Alternatives. Coatings 2021, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.; Somme, A.; Venzon, C.M.; McConihe, E.-M. The Furniture. Available online: www.mykotecture.com/furniture-leather-team (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Hoitink, A. Not Grown, Not Sewn: NEFFA Robotic Textiles from Mycelium|Tocco. Available online: https://tocco.earth/article/neffa-robotic-textiles-from-mycelium/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Chittenden, T. Foraging for Fashion’s Future: The Use of Mycelium Materials and Fungi Intelligence in Fashion Design. Fash. Style Pop. Cult. 2025, 12, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morby, A. Aniela Hoitink Creates Dress from Mushroom Mycelium. Dezeen. 2016. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2016/04/01/aniela-hoitink-neffa-dress-mushroom-mycelium-textile-materials-fashion/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Wagenaar, D. The Next Smart Move. A Decision Support System for Urban Implementation of Smart Mobility Solutions. Master’s Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, T. Mycelium—Textile. Studio Tjeerd Veenhoven. 2021. Available online: www.tjeerdveenhoven.com/portfolio_page/mycelium-textile/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Montalti, M.; Babbini, S. Sustainable Materials Mycelium-Based Biomaterials. Ephea®. 2022. Available online: https://ephea.bio/product/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Hendrikx, B. Loop Living CocoonTM. Available online: https://loop-biotech.com/product/living-cocoon/?srsltid=AfmBOorLtYnDrUc2NftVt81I3_dwrK7PzSnWELbdTAAlOtSx-PtTCoGc (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Khan, R. Furf Design Studio Grows Mycelium in 3D Printed Molds to Sculpt Sustainable Divine Deities. Designboom|Architecture & Design Magazine. 2022. Available online: https://www.designboom.com/art/furf-design-studio-grows-mycelium-3d-printed-molds-sculpt-sustainable-divine-deities-12-26-2022/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Gerrard, G. Fantastic Fungi: Harnessing the Magic of Mycelium to Create Striking Sculptures. Available online: https://www.lboro.ac.uk/alumni/news/2022/october/graduate-creates-sculptures-using-fungi/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Howarth, D. Fungi Kingdom Bio-Art Installation Offers Contemplative Space in Buenos Aires. Dezeen. 2023. Available online: www.dezeen.com/2023/12/02/fungi-kingdom-urban-farm-installation-buenos-aires-julio-oropel-jose-luis-zacarias-otin%cc%83ano/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Zeitoun, L. YUME YUME x MycoWorks Debut Head-to-Toe Outfit Made of Mycelium Leather. Designboom|Architecture & Design Magazine. 2023. Available online: www.designboom.com/design/yume-yume-mycoworks-debut-head-to-toe-outfit-made-of-mycelium-leather-reishi-interview-12-05-2023/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Dahmen, J. Mycelium Mockup. SALA. 2015. Available online: https://sala.ubc.ca/research/mycelium-mockup/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Hill, J. Studio Link-Arc’s “Inverted Architecture”. Available online: www.world-architects.com/en/architecture-news/found/studio-link-arcs-inverted-architecture (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Chowdhury, M.F.; Islam, Q.T.; Islam, Q.T. Ecovative: Growing a Sustainable Future in the Startup Ecosystem; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2025; ISBN 1-0719-6885-8. [Google Scholar]

- Šuput, D.; Popović, S.; Hromiš, N.; Ugarković, J. Degradable Packaging Materials: Sources, Application and Decomposition Routes. J. Process. Energy Agric. 2021, 25, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violano, A.; Del Prete, S. A Bio-Based Grown Material for Living Buildings. In Proceedings of the Beyond All Limits: International Congress on Sustainability in Architecture, Planning, and Design, Ankara, Turkey, 17–19 October 2018; pp. 762–768. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings, J. Grown Beneath Our Feet. Surf. Des. J. 2022, 24–29. Available online: https://www.jessicahemmings.com/uploads/general/4_Feature_GrownBeneathOurFeet_JessicaHemmings.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Bros, C. Monc Mycelium Packaging|Shortlists|Dezeen Awards 2024. Dezeen. Available online: www.dezeen.com/awards/2024/shortlists/monc-mycelium-packaging/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Thielen, A. UK Start-Up The Magical Mushroom Company Moves to Large-Scale Production Plastic-Free Packaging. Available online: www.bioplasticsmagazine.com/en/news/meldungen/20210315-UK-start-up-The-Magical-Mushroom-Company-moves-to-large-scale-production-plastic-free-packaging.php (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Yang, L.; Park, D.; Qin, Z. Material Function of Mycelium-Based Bio-Composite: A Review. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 737377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, M.; Cofta, G.; Doczekalska, B.; Bonenberg, A. Fungi in Mycelium-Based Composites: Usage and Recommendations. Materials 2022, 15, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vašatko, H.; Gosch, L.; Jauk, J.; Stavric, M. Basic Research of Material Properties of Mycelium-Based Composites. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.L.; Hotz, E.C.; Uehling, J.K.; Naleway, S.E. A Review of the Material and Mechanical Properties of Select Ganoderma Fungi Structures as a Source for Bioinspiration. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 3401–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazvinian, A.; Gursoy, B. Basics of Building with Mycelium-Based Bio-Composites. J. Green Build. 2022, 17, 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaleira, R.M.; Campos, M.J.; Alves, M.L. Mycelium-Based Composites: A New Approach to Sustainable Materials. In Sustainability and Automation in Smart Constructions; Rodrigues, H., Gaspar, F., Fernandes, P., Mateus, A., Eds.; Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 261–266. ISBN 978-3-030-35532-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza, F.A.; Reyes, J.C. Compressive Strength and Water Absorption Percentage of Pleurotus ostreatus and Ganoderma lucidum Mycelium. In Proceedings of the 21th LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology (LACCEI 2023): “Leadership in Education and Innovation in Engineering in the Framework of Global Transformations: Integration and Alliances for Integral Development”, Bogota, Colombia, 19–21 July 2023; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Obando, G.; Arcila, J.S.; Tolosa-Correa, R.A.; Valencia-Cardona, Y.L.; Montoya, S. Development and Characterization of Mycelium-Based Composite Using Agro-Industrial Waste and Ganoderma lucidum as Insulating Material. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuştaş, S.; Gezer, E.D. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Mycelium-Based Insulation Materials Produced from Desilicated Wheat Straws—Part A. BioRes 2024, 19, 1330–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Li, F.; Gao, Y.; Jin, J.; Jiang, W. A High-Performance Structural Material Based on Maize Straws and Its Biodegradable Composites of Poly (Propylene Carbonate). Cellulose 2021, 28, 11381–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, A.H.; El-Feky, M.S.; El-Tair, A.M.; Kohail, M. Wood Sawdust Waste-Derived Nano-Cellulose as a Versatile Reinforcing Agent for Nano Silica Cement Composites: A Systematic Study on Its Characterization and Performance. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecovative Design. Available online: https://ecovative.com/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- MycoWorks. Available online: www.mycoworks.com (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Mogu. Available online: https://mogu.bio/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- BIOHM. Available online: https://www.biohm.co.uk/mycelium (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- GROWN Bio BV. Available online: www.grown.bio (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Sullcapuma Morales, M.A. Modular Construction: A Sustainable Solution for Carbon Emission Reduction in the Construction Industry. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chippagiri, R.; Bras, A.; Sharma, D.; Ralegaonkar, R.V. Technological and Sustainable Perception on the Advancements of Prefabrication in Construction Industry. Energies 2022, 15, 7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, C.; Suchar, I.; Noonan, S.; Baidoo-Davis, J. Mycelium Filtration for Heavy Metal Removal from Water. In Proceedings of the 2025 Waste-Management Education Research Conference (WERC), Las Cruces, NM, USA, 23 May–13 June 2025; IEEE: Las Cruces, NM, USA, 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, E.; Narayan, S.; Lingam, D.; Blundell, R. Mycelium-Based Composites: An Updated Comprehensive Overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 2025, 79, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Ferrand, H. Critical Review of Mycelium-Bound Product Development to Identify Barriers to Entry and Paths to Overcome Them. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 450, 141859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Jujjavarapu, S.E.; Mahapatra, C. Green Sustainable Biocomposites: Substitute to Plastics with Innovative Fungal Mycelium Based Biomaterial. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; Zhang, M.; Dade-Robertson, M. Fungal Engineered Living Materials: The Viability of Pure Mycelium Materials with Self-Healing Functionalities. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2301875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, G.; Yemendzhiev, H.; Zaharieva, R.; Brazkova, M.; Koleva, R.; Stefanova, P.; Baldzhieva, R.; Vladev, V.; Krastanov, A. Mycelium-Based Composites Derived from Lignocellulosic Residual By-Products: An Insight into Their Physico-Mechanical Properties and Biodegradation Profile. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wylick, A.; Elsacker, E.; Yap, L.L.; Peeters, E.; De Laet, L. Mycelium Composites and Their Biodegradability: An Exploration on the Disintegration of Mycelium-Based Materials in Soil. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Bio-Based Building Materials, Barcelona, Spain, 16–18 June 2021; pp. 652–659. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Application | Name/Localization | Authors | Year | Fungus | Main Substrate Ingredients | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Building blocks | Hy-Fi Tower /Long Island City, NY, USA | David Benjamin, The Living (New York, NY, USA) | 2014 | G. lucidum | Straw and paper | [22] |

| 2 | Building blocks | MycoTree /Seul, KOR | ETH Zurich (CHE), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (DEU), Future Cities Laboratory (SGP) | 2017 | P. ostreatus | Straw and plant waste | [23] |

| 3 | Building blocks | Hack the Root/Mann Island, Liverpool, UK | Mae-Ling Lokko and Ecovative (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2018 | P. ostreatus | Sawdust and hemp | [24] |

| 4 | Building blocks | Mycelium Composites /Emeryville, CA, USA | MycoWorks (Emeryville, CA, USA) | 2016 | G. lucidum | Straw and paper | [25] |

| 5 | Building blocks | The Hayes Pavilion “6” /Glastonbury, UK | Simon Carroll and Biohm (London, UK) | 2023 | G. lucidum | Hemp waste | [26] |

| 6 | Building blocks | The Circular Garden/Milan, ITA | Carlo Ratti Associati (Torino, ITA) | 2019 | P. ostreatus | Sawdust and straw | [27] |

| 7 | Building blocks | In Vivo/Venice, ITA | Vinciane Despret, Bento Architecture (Lisbon, PRT) | 2023 | G. lucidum | Not mentioned | [28] |

| 8 | Building blocks | Myco-Temple /Port-de-Bouc, FRA | Côme Di Meglio | 2021 | G. lucidum | Sawdust | [29] |

| 9 | Building blocks | Mycelium on board /Breda, NLD | Shannon Peuling | 2022 | Trametes hirsuta, Ganoderma resinaceum, Lenzites betulina | Processed cellulose, rapeseed straw, hemp shives, and hemp fibers | [30] |

| 10 | Building blocks | MycoShell /Bethel Woods, NY, USA | Cornell University, Department of Architecture (Ithaca, NY, USA) | 2024 | G. lucidum | Corn cobs and hemp hurds | [31] |

| 11 | Building blocks | Myco-architecture off-planet Project /Moffett Field, CA, USA | NASA Ames Research Center (Moffett Field, CA, USA), Stanford University (Stanford, CA, USA) | 2016 | G. lucidum | Yard waste and wood chips | [32] |

| 12 | Building blocks | MycoHab /Windhuk, NAM | BioHab (Windhuk, NAM) | 2019 | P. ostreatus | Acacia mellifera | [33] |

| 13 | Building blocks | Symbiocene Living /London, UK | PLP Architecture, PLP Labs (London, UK) | 2023 | Not mentioned | Straw and wood chips | [33] |

| 14 | Building blocks | SAMOROST /České Budějovice, CZE | MYMO Association (Prague, CZE) | 2023 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [34] |

| 15 | Building units | Mycelium Pavilion /Troy, NY, USA | School of Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (Troy, NY, USA) | 2019 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [35] |

| 16 | Bricks | The Growing Pavilion /Ketelhuisplein, NLD | Company New Heroes (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2019 | G. lucidum | Plant fibers and organic composites | [36] |

| 17 | Bricks | Mycelium Brick /Green Island, NY, USA | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2014 | G. lucidum | Corn | [37] |

| 18 | Bricks | Glastonbury Mycelium Pavilion /Glastonbury, UK | Simon Carroll | 2024 | G. lucidum | Bioplastic made from seaweed | [38] |

| 19 | Bricks | Future Pavilion /Warsaw, POL | Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture (Warsaw, POL) | 2024 | G. lucidum | Wood | [39] |

| 20 | Bricks | Homegrown Wonderland /New York, NY, USA | Andre Kong Studio (London, UK) (with Ecovative Design [Green Island, NY, USA] and Arup [London, UK]) | 2024 | P. ostreatus | Hemp | [40] |

| 21 | Bricks | Lego-like bricks of fungi/Edinburgh, GB-SCT | PLP Architecture, PLP Labs (London, UK | 2024 | Not mentioned | Hemp | [41] |

| 22 | Self-supporting structures | Mycotecture Alpha, Düsseldorf, DEU | Phil Ross (inventor), Michael Sgambellone (design engineer) and Far West Fungi (Moss Landing, CA, USA) | 2009 | G. lucidum | Straw and paper | [42] |

| 23 | Self-supporting structures | Grown Structure (a mycelium chair), Paris, FRA | Klarenbeek and Dros (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2018 | P. ostreatus | Straw and sawdust | [43] |

| 24 | Self-supporting structures | MycoBuilt/Ithaca, NY, USA | Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (Ithaca, NY, USA) | 2018 | G. lucidum | Plant waste and organic composites | [44] |

| 25 | Self-supporting structures | El Monolito Micelio/Atlanta, GA, USA | Interspecific Collective (Mexico City, MEX) | 2019 | G. lucidum | Straw and agricultural waste | [45] |

| 26 | Self-supporting structures | MycoCreate 2.0 pavilion/Charlottesville, VA, USA | Benay Gürsoy Toykoç and Middle East Technical University, Department of Architecture (Ankara, TUR) | 2022 | Not mentioned | Organic waste | [46] |

| 27 | Self-supporting structures | MyCera structures/Graz, AUT | Graz University of Technology, Institute of Architecture and Media (Graz, AUT) | 2022 | P. ostreatus | Wood and sawdust | [47] |

| 28 | Self-supporting structures | BioKnit/London, UK | The Hub for Biotechnology and the Built Environment (Newcastle, UK) | 2023 | Not mentioned | Sawdust | [48] |

| 29 | Column | Op’t Oog Columns/Begijnendijk, BEL | Blast Studio (London, UK) | 2022 | Not mentioned | Paper coffee cups | [49] |

| 30 | Column | Woven mycelium/Venice, ITA | Polytechnic University of Milan, Architecture and Civil Engineering of the Built Environment, Material Balance Research (Milano, ITA) | 2021 | G. lucidum | Hemp and rattan | [50] |

| 31 | Column | Scan The World/London, UK | Robbie Jenkins | 2022 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [51] |

| 32 | Insulation panel | Ecovative’s Mushroom Tiny House/Green Island, NY, USA | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2013 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [52] |

| 33 | Insulation panel | Insulation panel/Hilversum, NLD | Grown.bio (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2016 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [53] |

| 34 | Insulation panel | Mykoslab/Bristol, UK | Mykor (Bristol, UK) | 2022 | G. lucidum | Cellulose | [54] |

| 35 | Facade panels | Crema Lab Façade/Curitiba, BRA | FURF Design Studio (Curitiba, BRA) and MUSH Design (Rotterdam, NLD) | 2024 | G. lucidum | Corn, wheat, soy, beans, and agricultural leftovers | [55] |

| 36 | Remediation of industrial and construction waste | Industrial Waste Bioremediation/Bolingbrook, IL, USA | Mycocycle (Bolingbrook, IL, USA) | 2023 | Not mentioned | Construction and industrial waste materials | [56] |

| 37 | Soil regeneration and reforestation | Life Box/Olympic Rainforest, WA, USA | Paul Stamets and Fungi Perfecti (Olympia, WA, USA) | 2025 | Not mentioned | Organic plant material and seeds | [57] |

| 38 | Bioremediation of oil-contaminated soil | Oil Spill Remediation/Olympic Rainforest, WA, USA | Paul Stamets and Fungi Perfecti (Olympia, WA, USA) | 2007 | P. ostreatus | Hydrocarbon-contaminated soil | [58] |

| 39 | Degradation of plastic polymers | Fungi Mutarium/Utrecht, NLD | Katharina Unger and the University of Utrecht, Faculty of Science (Utrecht, NLD) | 2024 | Not mentioned | Polyurethane and plastic waste | [59] |

| 40 | Water purification using biofiltration | Mycofiltration for Water Purification, Green Island, NY, USA | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2019 | P. ostreatus | Polluted water (bacteria, metals, chemicals) | [60] |

| No. | Application | Name | Authors | Year | Fungus | Main Substrate Ingredients | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Furniture | Mycelium Chair | Eric Klarenbeek | 2013 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [61] |

| 2 | Furniture | MYX | Jonas Edvard and Kasper Kjaergaard | 2013 | G. lucidum | Linen fibers | [62] |

| 3 | Furniture | Mycelium + Timber | Sebastian Cox and Ninela Ivanova | 2017 | G. lucidum | Wood waste | [63] |

| 4 | Furniture | The Growing Lab | Maurizio Montalti and Officina Corpuscoli (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2015 | P. ostreatus | Various agricultural byproducts | [64] |

| 5 | Furniture | Rongo Design furniture | Rongo Design (Cluj-Napoca, ROU) | 2021 | Not mentioned | Coffee grounds and agroindustrial waste | [65] |

| 6 | Furniture | Endless pot, endless vase | Blast Studio (London, UK) | 2022 | Not mentioned | Cardboard packaging and coffee cups | [66] |

| 7 | Furniture | Toad Stool | Ed Linacre, Philippa Abbott, and Mycelium Studios (Melbourne, VIC, AUS) with Brendon Morse | 2021 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [67] |

| 8 | Lighting | Conch light | Marc Theodoor van der Voorn and NEFFA (Utrecht, NLD) | 2018 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [68] |

| 9 | Lighting | MushLume Lighting Collection | Danielle Trofe | 2014 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [69] |

| 10 | Lighting | Mycelium Lights | Nir Meri Studio and Biohm (London, UK) | 2018 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [70] |

| 11 | Lighting | Luminaria Hogar | Ola Luminárias Acústicas (Curitiba, BRA), and Mush Mycotechnology Design (Ghent, BEL) | 2024 | Not mentioned | Corn, wheat, soy, beans, and agricultural leftovers | [71] |

| 12 | Acoustic panels | Mogu Acoustic Panels | Mogu (Inarzo, ITA) | 2019 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [72] |

| 13 | Acoustic panels | FIKA acoustic panels | AllSfär (Swindon, UK) | 2023 | G. lucidum | Hemp | [73] |

| 14 | Acoustic pannels | Acoustic panels | MYCEEN OÜ (Tallinn, EST) | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Industrial waste | [74] |

| 15 | Acoustic pannels | Fumo panels | mylab (Copenhagen, DNK) | 2021 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [75] |

| 16 | Acoustic and thermal insulation panels | Acoustic and thermal insulation panels | RongoDesign (Cluj-Napoca, ROU) | 2021 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [76] |

| 17 | Decorative structures | Mycelium Tiles | Terreform ONE (New York, NY, USA) | 2017 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [77] |

| 18 | Decorative structures | MycoBoard | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2016 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [78] |

| 19 | Decorative panels | Growing a mycelium panel | Antoni Gandia | 2014 | G. lucidum | Wheat husks | [79] |

| 20 | Decorative structures | Fungal Futures | Katharina Unger | 2013 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [80] |

| 21 | Flooring | Mogu Floor | Mogu (Inarzo, ITA) | 2019 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [81] |

| 22 | Flooring | Mycelium panels | Charlotte Kamman, Mark Fretz | 2014 | G. lucidum | Straw, sawdust, and hemp | [82] |

| 23 | Flooring | Myco-Alga Tiles | bioMATTERS (Vilnius, LTU) | 2023 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [83] |

| 24 | Flooring | Mycelium Flooring System | Stanislaw Młyński and Academy of Fine Arts and Design (Katowice, POL) | 2020 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [84] |

| 25 | Flooring | Grow It Yourself (GIY) Flooring | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2016 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [85] |

| 26 | Flooring | Orbit Floor-standing screens | AllSfär (Swindon, UK) | 2023 | G. lucidum | Hemp | [86] |

| 27 | Upholstery | Reishi™ | MycoWorks (Emeryville, CA, USA) | 2020 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [87] |

| 28 | Upholstery | Mylo™ | Bolt Threads (Emeryville, CA, USA) | 2018 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [88] |

| 29 | Upholstery | Muskin | Life Materials S.r.l. (Turin, ITA) | 2015 | Phellinus ellipsoideus | Agricultural waste | [89] |

| 30 | Upholstery | The furniture leather | MYKOS, University of California (Davis, CA, USA) and Yunnan Arts University (Kunming, CHN) | 2019 | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste | [90] |

| 31 | Upholstery | Parycel shell | NEFFA (Utrecht, NLD) | 2016 | G. lucidum | Agricultural waste | [91] |

| 32 | Upholstery | Forager™ Foams and Hides | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2022 | G. lucidum | Not mentioned | [92] |

| 33 | Textiles | Mycotex (a dress from mycelium) | Aniela Hoitink and NEFFA (Utrecht, NLD) | 2016 | G. lucidum and Fomes fomentarius | Not mentioned | [93] |

| 34 | Textiles | Mylium | Mylium B.V. (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2022 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [94] |

| 35 | Textiles | SashiFungi | School for Thinking Visual (Milano, ITA) | 2021 | P. ostreatus | Not mentioned | [95] |

| 36 | Textiles | Ephea | Vegea S.r.l. (Milano, ITA) | 2022 | P. ostreatus | Not mentioned | [96] |

| 37 | Coffin and urn | The loop cocoon | Loop Biotech (Delft, NLD) | 2020 | G. lucidum | Hemp fibers | [97] |

| 38 | Sculptures | Faith | FURF Design Studio (Curitiba, BRA) | 2022 | G. lucidum | Corn, wheat, soy, beans, and agricultural wastes | [98] |

| 39 | Sculptures | Mushroom of immorality | Georgia Gerrard and Kingston University, Kingston School of Art (London, UK) | 2022 | G. lucidum | Alpaca wool, sheep wool, and straw | [99] |

| 40 | Art installation | Fungi Kingdom bio-art | Julio Oropel and Jose Luis Zacarias Otiñano (in Buenos Aires, ARG) | 2023 | G. lucidum, P. ostreatus, and Cyclocybe aegerita | Not mentioned | [100] |

| 41 | Art installation | Living mycelium dunes | YUME YUME and MycoWorks (Emeryville, CA, USA) | 2023 | G. lucidum | Not mentioned | [101] |

| 42 | Art installation | Mycelium mockup | AFJD Studio (Vancouver, BC, CAN) | 2015 | P. ostreatus | Sawdust | [102] |

| 43 | Art installation | Inverted architecture | Studio Link-Arc (New York, NY, USA) | 2022 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [103] |

| 44 | Packaging | Mushroom® packaging (myco foam) | Ecovative Design (Green Island, NY, USA) | 2010 | P. ostreatus | Grain husks and straw | [104] |

| 45 | Packaging | MOGU packaging | MOGU (Inarzo, ITA) | 2015 | G. lucidum | Plant fibers | [105] |

| 46 | Packaging | Eco Packaging and DIY kits | Grown.bio (Amsterdam, NLD) | 2018 | P. ostreatus | Seed husks and wood chips | [106] |

| 47 | Packaging | Mycelium packaging | Mycotech Lab (Bandung, IDN) | 2015 | G. lucidum | Bamboo fibers | [107] |

| 48 | Packaging | Handcrafted packaging using Reishi mycelium leather alternative | MycoWorks (Emeryville, CA, USA) | 2013 | G. lucidum | Plant fibers and sawdust | [87] |

| 49 | Packaging | MONC Mycelium packaging | MONC (London, UK) | 2020 | P. ostreatus | Rice husks and plant fibers | [108] |

| 50 | Packaging | Mushroom packaging | Magical Mushroom Company (Esher, UK) | 2019 | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | [109] |

| Manufacturer | Fungal Species | Substrate | Mycelium Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecovative Design LCC (Green Island, NY, USA) [121] | P. ostreatus, G. lucidum | Agricultural waste: rice husks, straw, seed husks, sawdust | Eco-friendly packaging, composite materials, MycoFlex (flexible textiles) |

| MycoWorks Inc. (Emeryville, CA, USA) [122] | G. lucidum | Sawdust, agricultural waste, organic biomass | Reishi™ (leather-like material), leather finishes (fashion, interior design) |

| MOGU S.r.l. (Inarzo, ITA) [123] | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste: straw, hemp waste, organic residues | Acoustic panels, flooring, decorative elements made from mycelium |

| Biohm Ltd. (London, UK) [124] | P. ostreatus | Sawdust, straw, organic waste | Mycelium insulation panels, bio-based construction materials |

| Grown.bio B.V. (Amsterdam, NLD) [125] | P. ostreatus | Agricultural waste: straw, sawdust, organic biomass | Furniture (tables, chairs, lamps), decorative items, packaging, architectural elements |

| Category | Trend | Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Bricks | An upward trend, especially in recent years | Shows growing interest and development of building materials using mycelium |

| Building blocks | A consistent growing trend, the most prominent among others | Shows growing interest and development of building materials using mycelium |

| Self-supporting structures | A moderate and steady trend | Reflects potential in structural and architectural applications due to the mycelium’s natural properties |

| Column | Limited with a slight growth | Suggests that this is not a primary focus area for mycelium applications |

| Insulation and facade panels | Slight growth, especially in recent years | Indicates the development in this field in recent years |

| Remediation | Growth, especially in recent years | Highlights the development in this field in recent years |

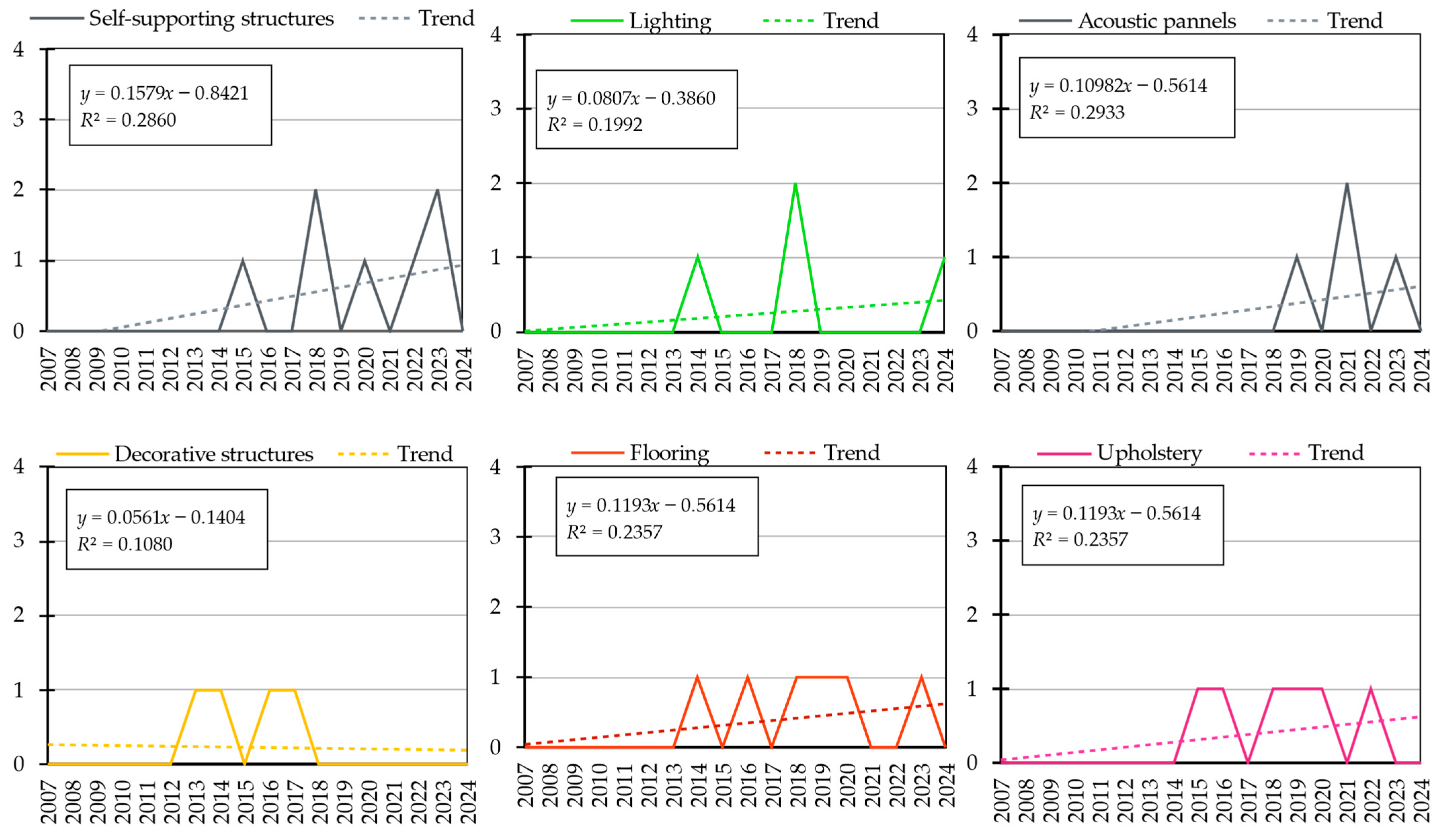

| Category | Trend | Insight |

|---|---|---|

| Furniture | Slight upward trend | Occasional interest, indicating a growing niche for innovative uses of mycelium in furniture. |

| Lighting | Irregular but increasing | Shows growing interest in aesthetic and functional lighting solutions using mycelium. |

| Acoustic Panels | Moderate and steady trend | Reflects potential in acoustic insulation applications due to the natural properties of mycelium. |

| Decorative Structures | Limited with a slight decline | Suggests that this is not a primary focus area for mycelium applications. |

| Flooring | Moderate and consistent growth | Indicates practical uses of mycelium in interior design and architecture. |

| Upholstery | Moderate and consistent growth | Highlights potential for further adoption in interior applications. |

| Textiles | Limited and sporadic | The remainder is experimental, with few projects exploring this category. |

| Sculptures and Art Installations | Significant upward trend | Reflects growing popularity in the creative and artistic industries. |

| Packaging | Relatively stable | Aligns with sustainable packaging solutions and shows moderate adoption. |

| Category | Extrapolation | Future Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Furniture | Steady growth is expected as sustainability becomes a priority, creating a niche for innovative, modular, or multifunctional designs. | Disruption in traditional furniture manufacturing and adoption by eco-friendly brands are expected. |

| Lighting | Rising interest in esthetic and functional designs is expected, as is growing recognition of its sustainability benefits and unique appearance. | Mainstream adoption of eco-conscious design is expected in residential, commercial, and public spaces. |

| Acoustic Panels | Continued steady growth is expected due to its natural sound-absorbing properties, making this material appealing in sustainable architecture. | It is expected to become widely used in residential and commercial soundproofing projects, with increased demand in the building industry. |

| Decorative Structures | The decline suggests limited growth potential; however, niche applications in art and design may persist. | It is unlikely that this trend will become a mass-market trend, but it may continue to find a home in specialized artistic projects. |

| Flooring | Moderate and consistent growth is expected, with sustainable building materials driving adoption. | It is expected to become mainstream in green building projects and prominent in eco-conscious residential and commercial developments. |

| Upholstery | Steady adoption as an alternative to synthetic materials in interior design is expected. | Strong growth in eco-friendly living and luxury markets, particularly in furniture design, is expected. |

| Textiles | The integration of mycelium in textiles remains limited and experimental, primarily due to persistent challenges in achieving scalability and durability. | The future can bring long-term breakthroughs for eco-conscious fashion and functional fabrics, but near-term growth remains a niche market. |

| Sculptures and Art | A significant upward trend is expected in line with an increasing use in creative and artistic industries. | The signature materials of environmental art are expected to feature more heavily in future installations and sculptures. |

| Packaging | Stable growth is expected as it represents a sustainable alternative to plastic, particularly for food and consumer goods. | Driven by anti-plastic initiatives, broader adoption is expected across the e-commerce, food, and electronics industries. |

| Bricks | The strong upward trend suggests continued innovation and increased adoption of mycelium-based bricks in sustainable construction. These bricks may become more competitive with traditional materials as material science advances. | This could lead to greater regulatory support and certification for sustainable building materials. |

| Building Blocks | Given the consistent and prominent growth, mycelium building blocks are likely to become a mainstream choice in modular, lightweight construction systems. | Enhanced integration of mycelium blocks into global supply chains could transform affordable housing and disaster relief construction. |

| Self-Supporting Structures | The steady trend suggests a growing niche market for mycelium in architectural innovation. We may see more experimental and functional uses in art installations as designers explore its unique properties. | In time, advances in engineering techniques may allow mycelium to play a more substantial role in permanent structural applications. |

| Columns | Limited growth suggests that this category may remain secondary unless significant breakthroughs in material strength and load-bearing capacity occur. | While not a primary focus, mycelium columns might find specialized applications in lightweight structures, artistic designs, or low-load installations. |

| Insulation and Facade Panels | Recent growth points to increasing adoption, particularly in energy-efficient buildings. | Mycelium panels could become standard in green construction, especially in retrofitting existing buildings |

| Remediation | The noticeable growth suggests expanding research and deployment in this field. Mycelium’s ability to degrade pollutants and restore ecosystems is likely to become a critical tool in environmental management. | Mycelium-based remediation could revolutionize the way industries handle pollution, offering scalable solutions for soil restoration, water purification, and even carbon sequestration. Partnerships with environmental organizations and governments may accelerate adoption. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewandowska, A.; Sydor, M.; Bonenberg, A. A Review of Mycelium-Based Composites in Architectural and Design Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11350. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411350

Lewandowska A, Sydor M, Bonenberg A. A Review of Mycelium-Based Composites in Architectural and Design Applications. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11350. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411350

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewandowska, Anna, Maciej Sydor, and Agata Bonenberg. 2025. "A Review of Mycelium-Based Composites in Architectural and Design Applications" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11350. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411350

APA StyleLewandowska, A., Sydor, M., & Bonenberg, A. (2025). A Review of Mycelium-Based Composites in Architectural and Design Applications. Sustainability, 17(24), 11350. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411350