A Sustainable Monitoring and Predicting Method for Coal Failure Using Acoustic Emission Event Complex Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

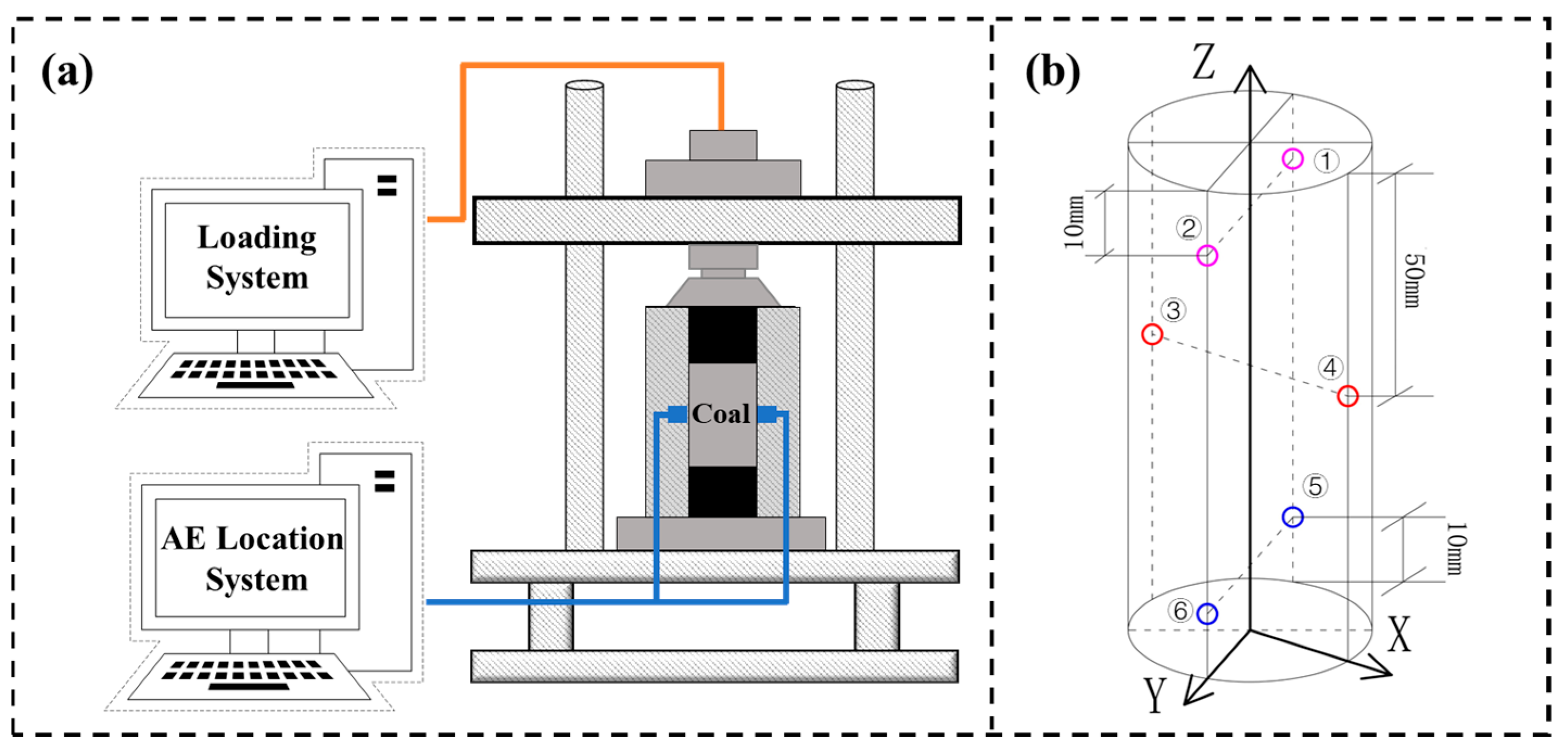

2. Materials and Methods

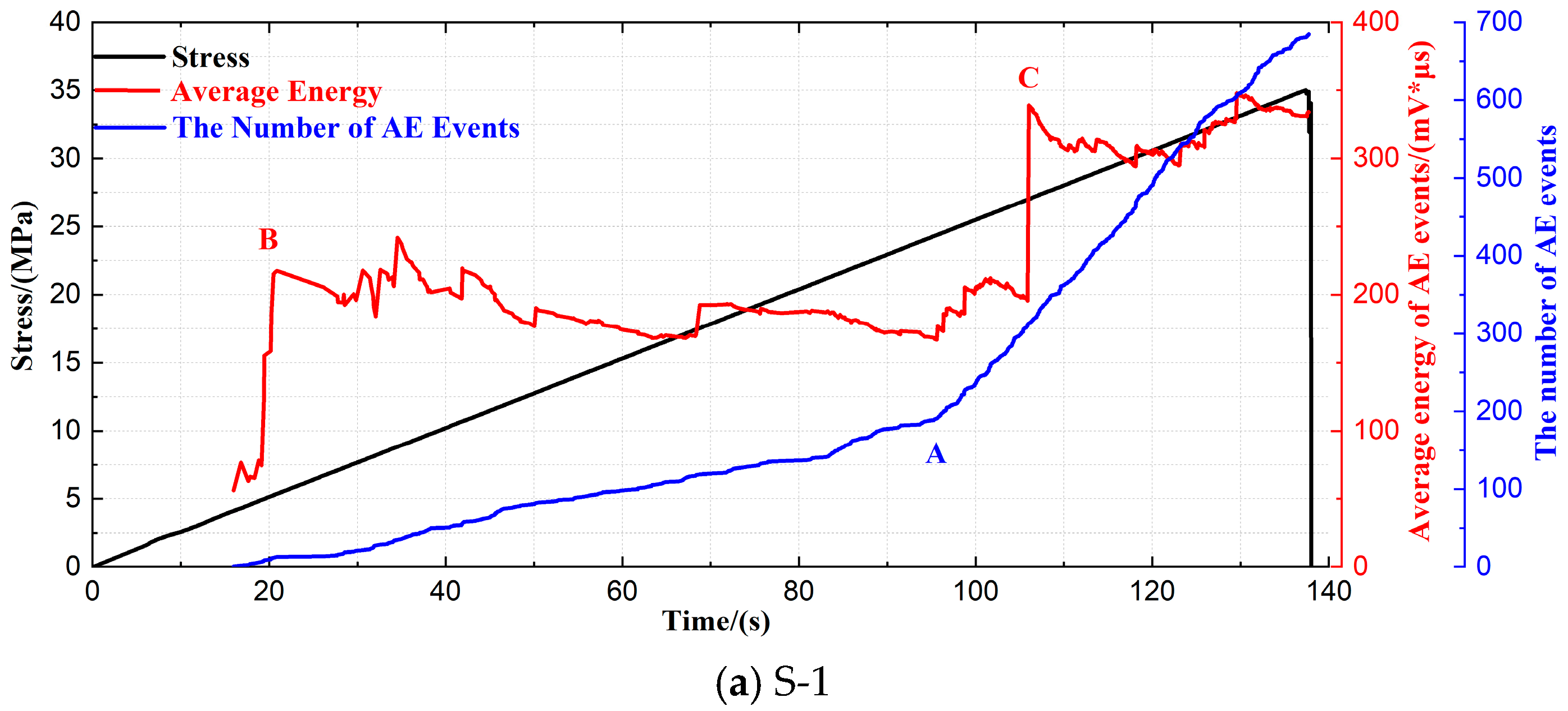

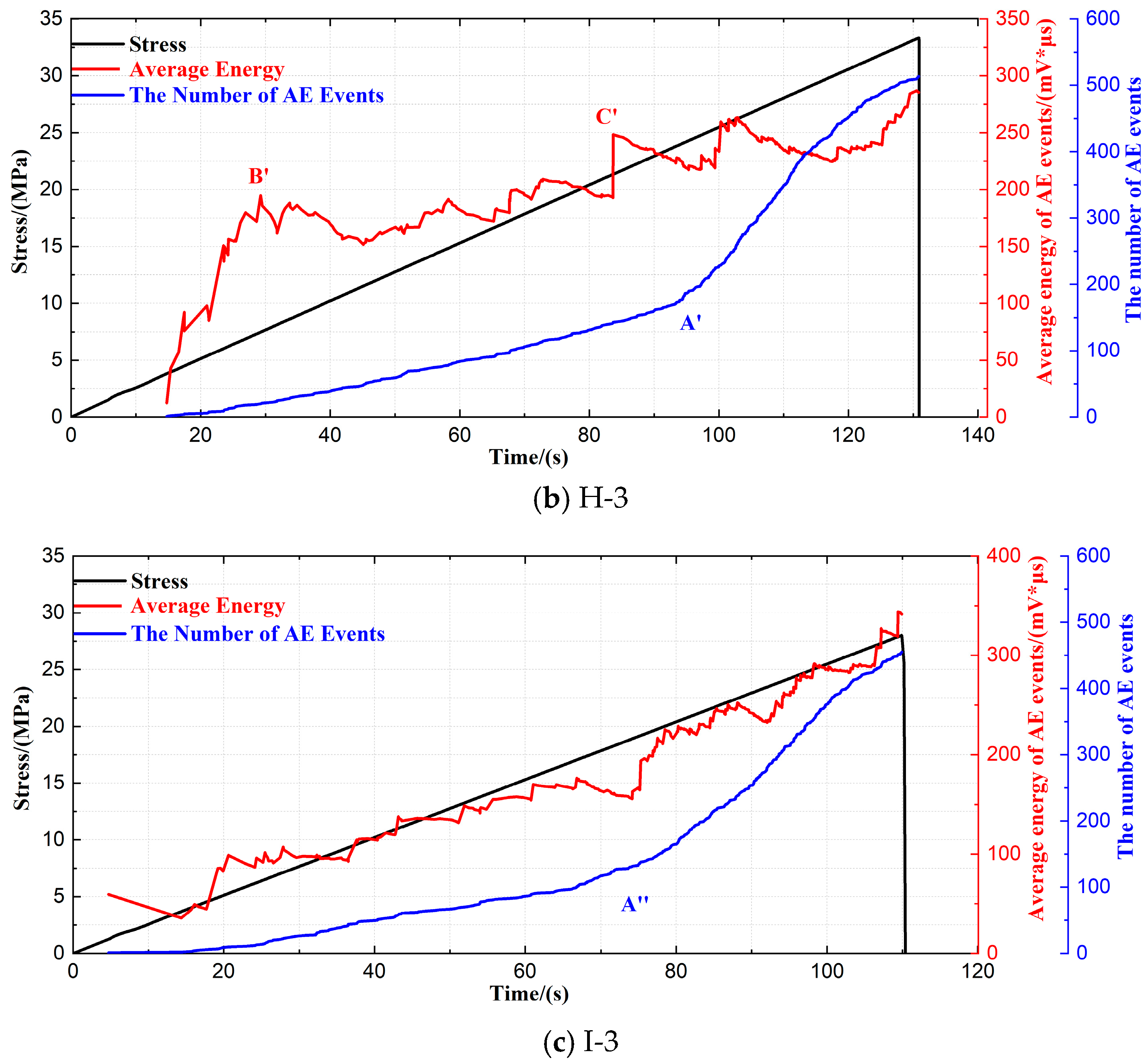

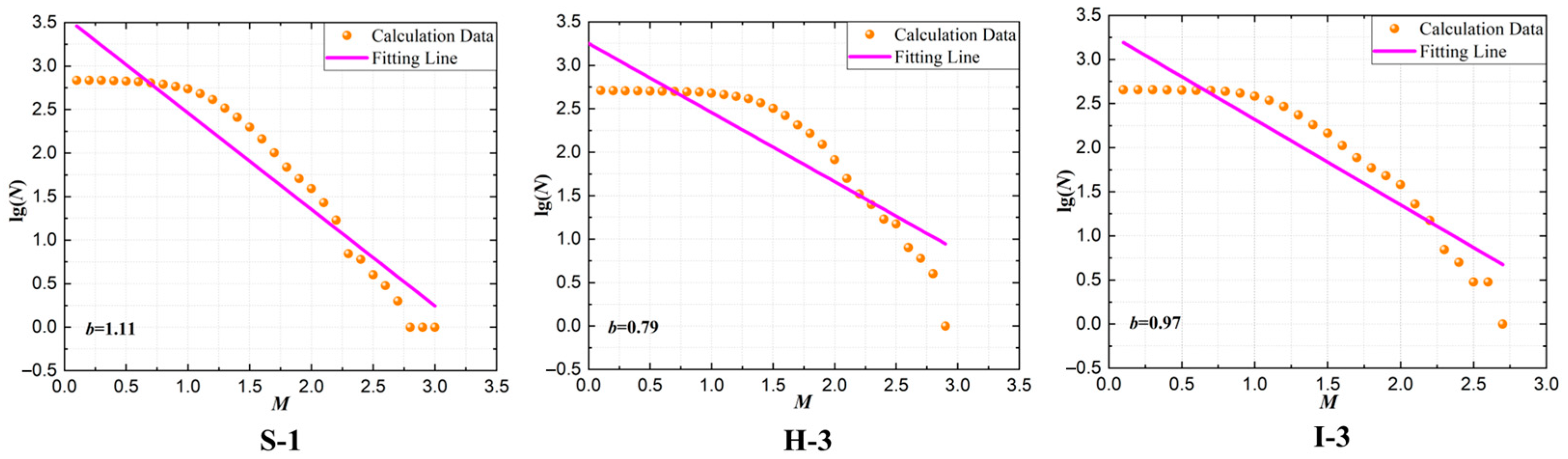

3. Experimental Results

4. Construction of a Complex Network Based on Multidimensional Correlation of AE Events

4.1. Quantitative Characterization of Multidimensional Correlation of AE Events

4.2. Construction of Complex Network for the AE Events

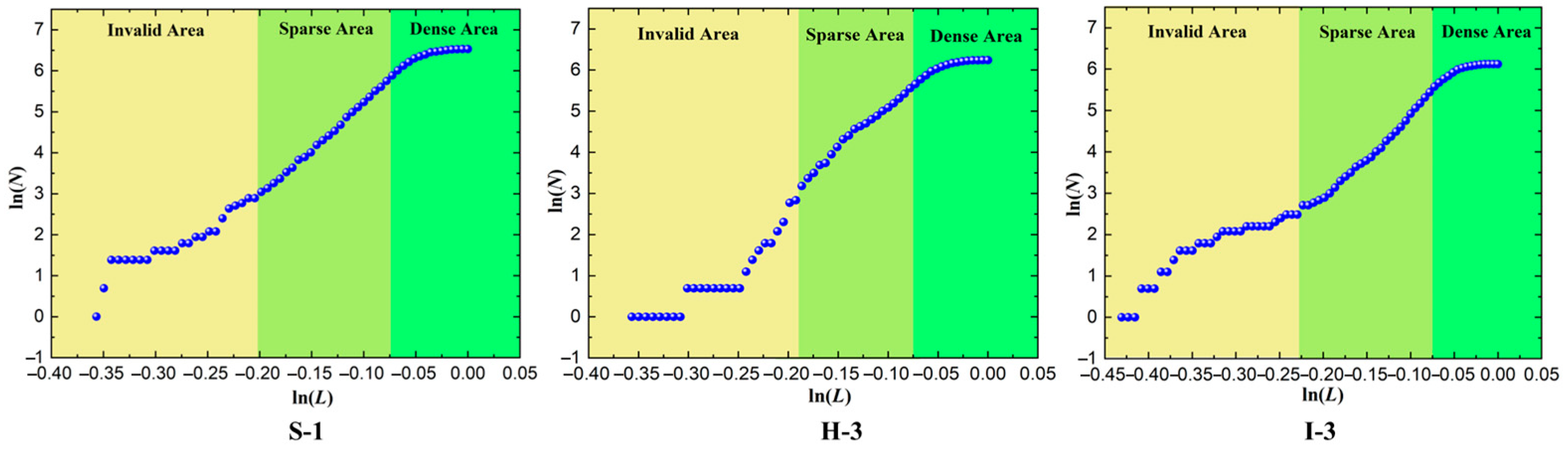

5. Quantitative Analysis of the Complex Network

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; Wang, A.; Li, J. Spatiotemporal air pollutant and carbon footprints of China’s coal sector and their synergetic mitigation pathway towards 2035. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 224, 108563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Bi, R.; Khandelwal, M.; Li, G.; Zhou, J. Occurrence mechanism and prevention technology of rockburst, coal bump and mine earthquake in deep mining. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour. 2024, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Xu, H.; Shan, P.; Hu, Q.; Ding, W.; Yang, S.; Yan, Z. Research on the mechanism of rockburst induced by mined coal-rock linkage of sharply inclined coal seams. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2024, 31, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Gao, F.; Xu, G.; Ren, H. Mechanical behaviors of coal measures and ground control technologies for China’s deep coal mines-A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2023, 15, 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ma, S.; Wang, K.; Yang, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, A.; Shu, L. Stress and permeability evolution of high-gassy coal seams for repeated mining. Energy 2023, 284, 128601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shi, R.; Song, J.; Tian, Z.; Deng, D.; Jiang, Y. Mechanical model for the calculation of stress distribution on fault surface during the underground coal seam mining. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 144, 104765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, S.; Wang, E.; Li, Z. Rockburst mechanism in coal rock with structural surface and the microseismic (MS) and electromagnetic radiation (EMR) response. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 124, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, B.; Nie, L.; Liu, Z.; Tian, M.; Wang, S.; Su, M.; Guo, Q. Detecting and monitoring of water inrush in tunnels and coal mines using direct current resistivity method: A review. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2015, 7, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Li, F.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, L. Infrared radiation characterization of damaged coal rupture based on stress distribution and energy. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 28545–28555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishal, V.; Ranjith, P.G.; Singh, T.N. An experimental investigation on behaviour of coal under fluid saturation, using acoustic emission. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 22, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Liu, S.-M.; Li, Z.-H. AE waveform characteristics of rock mass under uniaxial loading based on Hilbert-Huang transform. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xie, H.; Zhang, R.; Li, C.; Wang, M.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Acoustic emission characteristics and damage evolution of coal at different depths under triaxial compression. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Du, P. Acoustic emission characteristics of coal failure under triaxial loading and unloading disturbance. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 1043–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goszczynska, B.; Swit, G.; Trąmpczynski, W.; Krampikowska, A.; Tworzewska, J.; Tworzewski, P. Experimental validation of concrete crack identification and location with acoustic emission method. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2012, 12, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, L.; Li, M. Failure behaviour and acoustic emission characteristics of different rocks under uniaxial compression. J. Geophys. Eng. 2020, 17, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, V.; Kovalevska, I.; Krasnyk, V.; Chernyak, V.; Haidai, O.; Sachko, R.; Vivcharenko, I. Methodical principles of experimental-analytical research into the influence of pre-drilled wells on the intensity of gas-dynamic phenomena manifestations. Min. Miner. Depos. 2024, 18, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dai, F.; Gao, M.; Xu, N.; Zhang, C. Fractal analysis of acoustic emission during uniaxial and triaxial loading of rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2015, 79, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, X.; Khan, M. Comparative study on fracture characteristics of coal and rock samples based on acoustic emission technology. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 111, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X. Evolution of b-value and fractal dimension of acoustic emission events during shear rupture of an immature fault in granite. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.K.; Small, M.; Kurths, J. Complex network analysis of time series. Europhys. Lett. 2017, 116, 50001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, R.-R.; Lü, L.; Hu, M.-B.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.-C. Percolation on complex networks: Theory and application. Phys. Rep. 2021, 907, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiesi, M.; Paczuski, M. Complex networks of earthquakes and aftershocks. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2005, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, D.; Valdivia, J.; Bucheli, V. A revision of seismicity models based on complex systems and earthquake networks. J. Seismol. 2022, 26, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.O.; Thompson, B.D.; Young, R.P. Complex networks and waveforms from acoustic emissions in laboratory earthquakes. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2014, 21, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Ge, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q. The complexity of the fracture network in failure rock under cyclic loading and its characteristics in acoustic emission monitoring. J. Geophys. Eng. 2018, 15, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ge, H.; Wang, X.; Meng, F. Shale failure processes and spatial distribution of fractures obtained by AE monitoring. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 41, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, E.; Li, N. Fractal characteristics of acoustic emission events based on single-link cluster method during uniaxial loading of rock. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2017, 104, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, H.; Pei, J. Box-counting methods to directly estimate the fractal dimension of a rock surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 314, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahy, C.; Seal, A.; Mahato, N.K.; Bhattacharjee, D. Differential box counting methods for estimating fractal dimension of gray-scale images: A survey. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2019, 126, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhao, C.; Cai, X.; Huang, Y. Three-dimensional modeling and analysis of fractal characteristics of rupture source combined acoustic emission and fractal theory. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 160, 112308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, E.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research on macroscopic mechanical properties and microscopic evolution characteristic of sandstone in thermal environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 366, 130152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.P.; Liu, J.F.; Ju, Y.; Li, J.G.; Xie, L.Z. Fractal property of spatial distribution of acoustic emissions during the failure process of bedded rock salt. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutenberg, B.; Richter, C.F. Frequency of earthquakes in California. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 1944, 34, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.L.; Zhou, H.L. Temporal and Spatial Statistical Characteristics of Earthquakes in China by Single-Link Cluster Method. Chin. J. Geophys. 2000, 43, 200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, E.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Z. Damage evolution analysis of coal samples under cyclic loading based on single-link cluster method. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 152, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, F.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Gao, J. Deep learning resilience inference for complex networked systems. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Xiang, J.; Peng, Y. Complex Network Modeling and Analysis of Microfracture Activity in Rock Mechanics. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Wang, B.; Sheng, J.; Long, J.; Khan, N.; Sun, Z. Identifying vital nodes from local and global perspectives in complex networks. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 186, 115778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A. Greedy algorithms: A review and open problems. J. Inequalities Appl. 2025, 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favorskaya, A.V.; Khokhlov, N.I.; Podlesnykh, D.A. A Modification of Adaptive Greedy Algorithm for Solving Problems of Fractured Media Geophysics. Supercomput. Front. Innov. 2024, 11, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Production Regions | Abbreviation | Type | Average Compressive Strength (MPa) | Average Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanxi | S | Anthracite | 36.62 | 1.78 |

| Hebei | H | Anthracite | 31.15 | 1.56 |

| Inner Mongolia | I | Anthracite | 27.78 | 1.62 |

| Number | No.1 | No.2 | No.3 | No.4 | No.5 | No.6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X (mm) | 0 | 0 | −25 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Y (mm) | −25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | −25 | 25 |

| Z (mm) | 90 | 90 | 50 | 50 | 10 | 10 |

| Sampling Rate | Threshold | Resonant Frequency | PDT | HDT | HLT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 MSPS | 40 dB | 300 kHz | 220 μs | 800 μs | 1000 μs |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | ||||||

| S | 2.79 | 2.53 | 2.61 | 2.46 | 2.58 | |

| H | 2.55 | 2.57 | 2.61 | 2.42 | 2.53 | |

| I | 2.46 | 2.44 | 2.47 | 2.29 | 2.38 | |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | ||||||

| S | 1.11 | 0.98 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 1.16 | |

| H | 1.02 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.66 | 0.92 | |

| I | 0.92 | 0.90 | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.87 | |

| Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | ||||||

| S | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | |

| H | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | |

| I | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y.; Wang, J. A Sustainable Monitoring and Predicting Method for Coal Failure Using Acoustic Emission Event Complex Networks. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411349

Zhang Z, Sun J, Ma Y, Wang J. A Sustainable Monitoring and Predicting Method for Coal Failure Using Acoustic Emission Event Complex Networks. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411349

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhibo, Jiang Sun, Yankun Ma, and Jiabao Wang. 2025. "A Sustainable Monitoring and Predicting Method for Coal Failure Using Acoustic Emission Event Complex Networks" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411349

APA StyleZhang, Z., Sun, J., Ma, Y., & Wang, J. (2025). A Sustainable Monitoring and Predicting Method for Coal Failure Using Acoustic Emission Event Complex Networks. Sustainability, 17(24), 11349. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411349