Enhancing Organizational Agility in Sustaining Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector: An Integrating Human-Technology-Organization Framework Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Organizational Agility and Agility Enablers

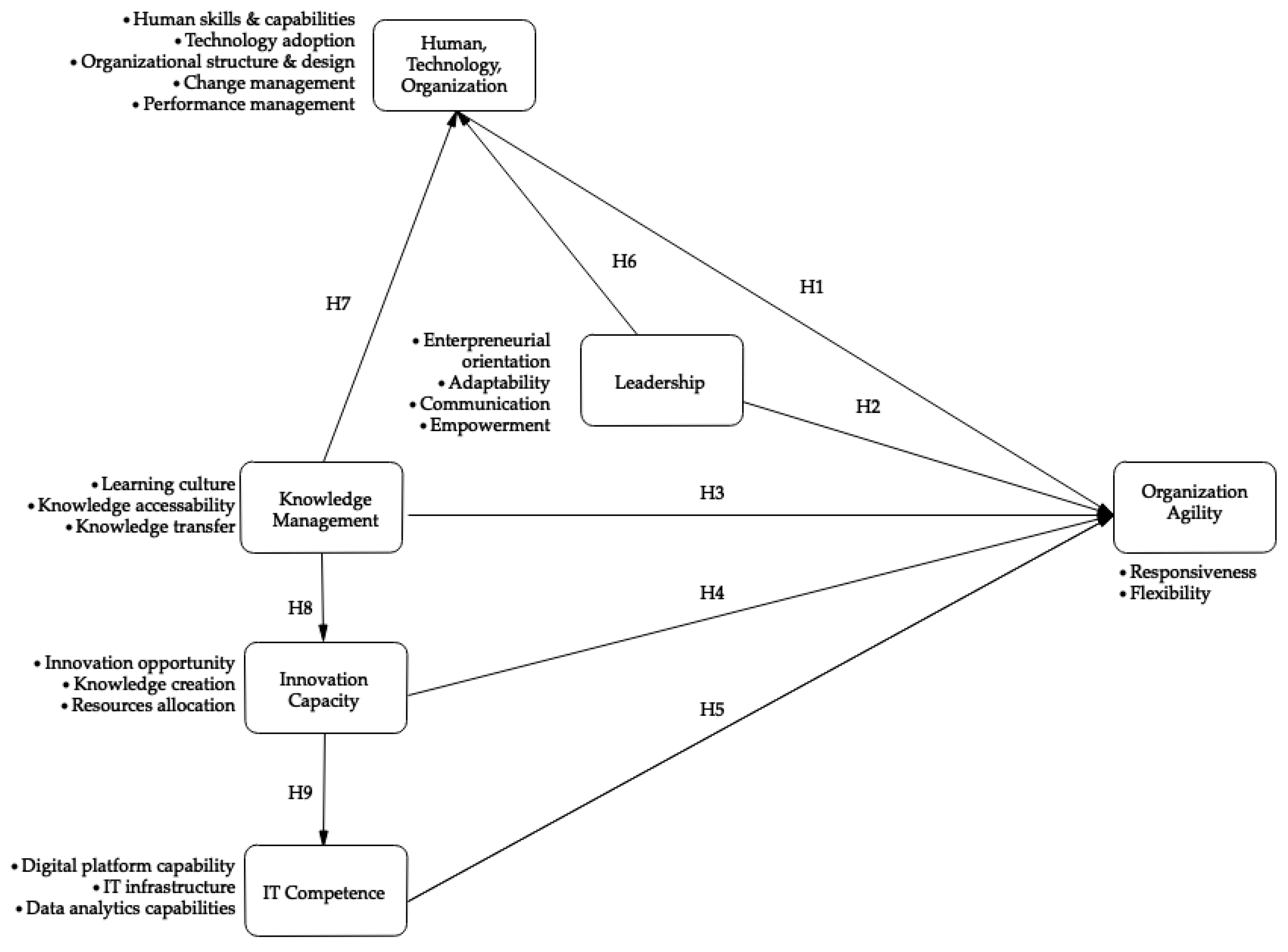

2.2. Proposed Framework

2.3. Hypothesis Development

2.3.1. Human–Technology–Organization (HTO)

2.3.2. Leadership

2.3.3. Knowledge Management

2.3.4. Innovation Capacity and IT Competence

2.3.5. Interaction Between Agility Enablers

- Relationship between leadership and human–technology–organization (HTO).

- Relationship between knowledge management and HTO.

- Relationship between knowledge management and innovation capacity.

- Relationship between innovation capacity and IT competence.

| No | Factors | References | Constructs | Indicator Codes (No of Question) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IT Competence | [18] | Digital platform capability (DPC) | DPC1-4 (4) | [18] |

| IT Infrastructure (ITI) | ITI1-4 (4) | [49,50] | |||

| Data Analytics Capabilities (DAC) | DAC1-4 (4) | [51] | |||

| 2 | Innovation capacity | [18] | Innovation opportunity (IO) | IO1-4 (4) | [47] |

| Knowledge creation (KC) | KC1-3 (3) | [11] | |||

| Resources allocation (RA) | RA1-4 (4) | [52] | |||

| 3 | Human–Technology–Organization (HTO) Relationship | [31,32,33] | Human skills & capabilities (HSC) | HSC1-5 (5) | [23] |

| Technology adoption (TA) | TA1-3 (3) | [33,53] | |||

| Organizational structure and design (OSD) | OSD1-3 (3) | [21,23,54] | |||

| Change management (CM) | CM1-4 (4) | [55] | |||

| Performance management (PM) | PM1-4 (4) | [56] | |||

| 4 | Leadership | [24,30] | Entrepreneurial orientation (ENT) | ENT1-2 (2) | [57] |

| Adaptability (ADA) | ADA1-3 (3) | [58] | |||

| Communication (COM) | COM1-4 (4) | [30,59] | |||

| Empowerment (EMP) | EMP1-3 (3) | [60] | |||

| 5 | Knowledge Management | [21] | Learning culture (LC) | LC1-2 (2) | [61] |

| Knowledge accessibility (KNO) | KNO1-2 (2) | [62,63] | |||

| Knowledge transfer (KT) | KT1-3 (3) | [21,64] | |||

| 6 | Organizational Agility | [10,15,27,65] | Responsiveness (RES) | RES1-3 (3) | [10,17] |

| Flexibility (FLE) | FLE1-2 (2) | [10,17] | |||

| Total | 6 Factors | 20 Constructs | 66 Indicators |

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants, Procedures, and Samples

3.2. Measures

3.3. Methodological Analysis

3.4. Homogeneity and Linearity

4. Results

4.1. Respondents and Demographic Characteristics

4.2. The Assessment of the Measurement Model

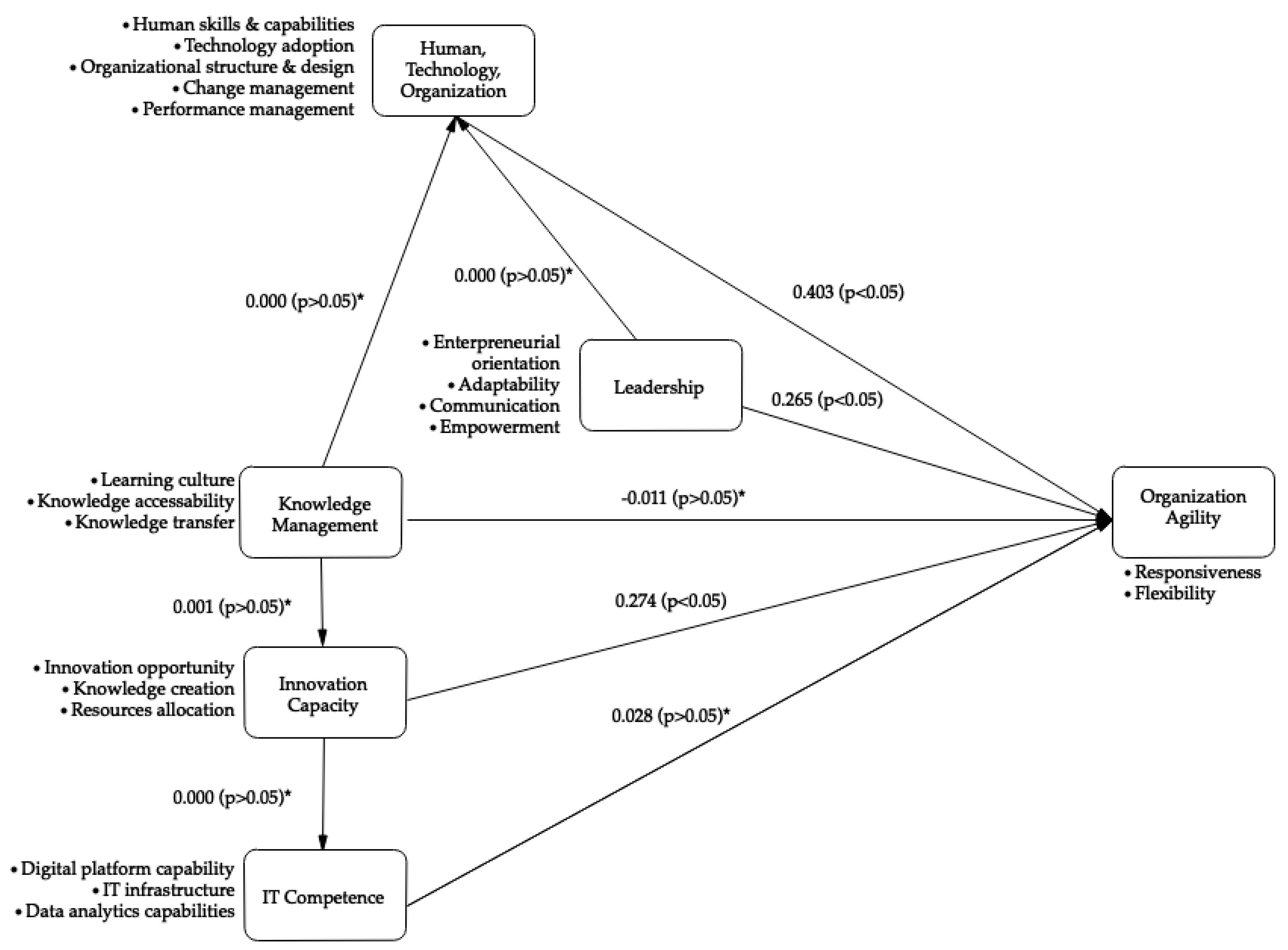

4.3. Structural Model Testing

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azizurrofi, A.A.; Mashari, D.P. Designing oil and gas exploration strategy for the future national energy sustainability based on statistical analysis of commercial reserves and production cost in Indonesia. Indones. J. Energy 2018, 1, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESDM. Menteri ESDM Minta Target Produksi Migas 2030 Dipercepat. 2022. Available online: https://migas.esdm.go.id/post/read/menteri-esdm-minta-target-produksi-migas-2030-dipercepat (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Aprizal, M.F.; Juanda, B.; Ratnawati, A.; Muin, A. Indonesian upstream oil & gas governance for sustainable innovation. J. Manaj. Organ. 2022, 13, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bundtzen, H.; Hinrichs, G. The link between organizational agility and VUCA—An agile assessment model. Socioecon. Chall. 2021, 5, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbeche, L. The Agile Organization: How to Build an Engaged, Innovative and Resilient Business, 2nd ed.; BusinessPro Collection: London, UK, 2018; pp. 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S.; Nagel, R.; Preiss, K. Agile Competitors and Virtual Organizations: Strategies for Enriching the Customer; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sherehiy, B.; Karwowski, W.; Layer, J.K. A review of enterprise agility: Concepts, frameworks, and attributes. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2007, 37, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowiak, A.; Oleśków-Szłapka, J. Agility capability maturity framework. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 17, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, R. Development of the organizational agility maturity model. In Proceedings of the Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems, Warsaw, Poland, 7–10 September 2014; pp. 1197–1206. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Sharifi, H. A methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organizations. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2000, 20, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsawan, I.W.E.; Hariyanti, N.K.D.; Atmaja, I.M.A.D.S.; Suhartanto, D.; Koval, V. Developing organizational agility in SMEs: An investigation of innovation’s roles and strategic flexibility. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsberg, D.; Callow, B.; Ryan, B.; Suthers, J.; Baker, P.A.; Richardson, J. Applying an organizational agility maturity model. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2018, 31, 1315–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtam, F.; Tourabi, A. Organizational agility assessment of a Moroccan healthcare organization in times of COVID-19. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. 2020, 5, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Patel, B.; Samuel, C.; Sutar, G. Designing of an agility control system: A case of an Indian manufacturing organization. J. Model. Manag. 2020, 15, 1591–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rehman, A.; Al-Zabidi, A.; AlKahtani, M.; Umer, U.; Usmani, Y.S. Assessment of supply chain agility to foster sustainability: Fuzzy-DSS for a Saudi manufacturing organization. Processes 2020, 8, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda, J.; Arias-Pérez, J. Information technology capabilities and organizational agility. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2019, 27, 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felipe, C.M.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal-Rodríguez, A.L. An explanatory and predictive model for organizational agility. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4624–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, T. Exploring the relationships between IT competence, innovation capacity and organizational agility. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2018, 27, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwandono, D.; Subriadi, A.P. IT and organizational agility: A critical literature review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, R.; Vrontis, D.; Belyaeva, Z.; Ferraris, A.; Czinkota, M.R. Strategic agility in international business: A conceptual framework for “agile” multinationals. J. Int. Manag. 2021, 27, 100737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.G.C.; Acosta, P.S.; Wensley, A.K.P. Structured knowledge processes and firm performance: The role of organizational agility. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocitto, M.; Youssef, M. The human side of organizational agility. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2003, 103, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, W.P.; Winkelhaus, S.; Grosse, E.H.; Glock, C.H. Industry 4.0 and the human factor—A systems framework and analysis methodology for successful development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 233, 107992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, N. Organizational evolution-how digital disruption enforces organizational agility. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 486–491. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Wang, T.; Teo, T.S.H.; Song, Q. Organizational agility through outsourcing: Roles of IT alignment, cloud computing and knowledge transfer. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteta, B.M.; Giachetti, R.E. A measure of agility as the complexity of the enterprise system. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2004, 20, 495–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.; Chiu, H.; Chu, P.Y. Agility index in the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2006, 100, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbeche, L. Organizational effectiveness and agility. J. Organ. Eff. 2018, 5, 302–313. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, A.T. Organizational agility: Ill-defined and somewhat confusing? A systematic literature review and conceptualization. Manag. Rev. Q. 2020, 71, 343–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagel, G. The effects of leadership behaviors on organization agility: A quantitative study of 126 U.S.-based business units. Manag. Organ. Stud. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karltun, A. Researcher-Supported work for change–improving the work situation of 15,000 postmen. In Proceedings of the Human Factors in Organizational Design and Management–IX, São Paulo, Brazil, 19–21 March 2008; pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karltun, J.; Karltun, A.; Berglund, M. Activity–the core of human-technology-organization. In Congress of the International Ergonomics Association; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 704–711. [Google Scholar]

- Karltun, J.; Vogel, K.; Bergstrand, M.; Eklund, J. Maintaining knife sharpness in industrial meat cutting: A matter of knife or meat cutter ability. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 56, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Kim, S.; Rouibah, K.; Shin, D. The moderating effects of leader member exchange for technology acceptance: An empirical study within organizations. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2021, 33, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, S.; Agusvina, N.; Lusa, S.; Sensuse, D.I. Knowledge management factors and its impact on organizational performance: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2023, 7, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Cln, A.I. Impact of knowledge management system in an organization: An overview. Samaru J. Inf. Stud. 2023, 23, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mardani, A.; Nikoosokhan, S.; Moradi, M.; Doustar, M. The relationship between knowledge management and innovation performance. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2018, 29, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simanaviciene, Z.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A.; Shaybakova, L. The Impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation. Adv. Econ. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 195, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Fernandez-Escobedo, R.; Cortes-Palacios, H.A.; Ramirez-Lemus, L. The relation between adoption of information and communication technologies and marketing innovation as a key strategy to improve business performance. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neziraj, E.; Shaqiri, A.B.; Pula, J.S.; Kume, V.; Krasniqi, B. The relation between information technology and innovation process in software and not software industries in Kosovo. J. Eur. Soc. Inf. Technol. 2018, 51, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, S.N.S.M.; Hirawaty, N.; Kamarulzaman, N.M.N.; Abdulhadi, A.H.I.; Hadiwiyanti, R. The moderating role of barriers to agility and their impacts on organizational performance. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2024, 13, 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaignanam, K.; Tuli, K.R.; Kushwaha, T.; Lee, L.; Gal, D. Marketing agility: The concept, antecedents, and a research agenda. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerur, S.; Mahapatra, R.; Mangalaraj, G. Challenges of migrating to agile methodologies. Commun. ACM 2005, 48, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, K.; Brendgens, F.M.; Gauster, S.P.; Matzler, K. Scaling organizational agility: Key insights from an incumbent firm’s agile transformation. Manag. Decis. 2023, 63, 1882–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlback, K.; Comella-Dorda, S.; Mahadevan, D. The Drawbacks of Agility. 2018. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-organization-blog/the-drawbacks-of-agility (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Taqi, A.; Talib, A. Leadership skills in the Kuwait oil & gas sector. Interdiscip. Soc. Stud. 2023, 2, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkees, M. Understanding the links between technological opportunism, marketing emphasis and firm performance: Implications for B2B. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.; Nguyen, P.; Le, N.; Tran, K. The relation among organizational culture, knowledge management, and innovation capability: Its implication for open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Siaus, K. Impact of business intelligence and IT infrastructure flexibility on competitive performance: An organizational agility perspective. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems 2011, Shanghai, China, 4–7 December 2011; pp. 2675–2685. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S.; Rath, S.K. Modelling the relationship between information technology infrastructure and organizational agility: A study in the context of India. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Darras, O.; Tanova, C. From big data analytics to organizational agility: What is the mechanism? SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingebiel, R.; Rammer, C. Resource allocation strategy for innovation portfolio management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azham, A.; Othman, Z.; Arshah, R.A.; Kamaludin, A. The suitability of technology, organization and environment (TOE) and socio technical system (STS) for assessing IT hardware support services (ITHS) Model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1874, 012040. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, R.; Brown, R.; Scanlon, M.; Rivera, A.; Karsh, B.T. Micro- and macroergonomic changes in mental workload and medication safety following the implementation of new health IT. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 49, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oreg, S.; Vakola, M.; Armenakis, A. Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2011, 47, 461–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D. The role of agility in the relationship between use of management control systems and organizational performance: Evidence from Korea and Japan. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2017, 33, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkosi, O.; Mire, M.S.; Tricahyadinata, I. The effects of entrepreneur orientation and strategic agility on SMEs business performance during the recession. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 6, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.; Lee, W.J. The venture firm’s ambidexterity: Do transformational leaders boost organizational learning for venture growth? Sustainability 2021, 13, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handscomb, C.; Honigmann, D.; Reddy, M. Unleashing the Power of Communication in Agile Transformations. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/the-organization-blog/unleashing-the-power-of-communication-in-agile-transformations (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Cyfert, S.; Szumowski, W.; Dyduch, W.; Zastempowski, M.; Chudzinski, P. The power of moving fast: Responsible leadership, psychological empowerment and workforce agility in energy sector firms. Heliyon 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, D.; Katic, M.; Burdon, S.; Gunsel, A. The Interplay among Organisational Learning Culture, Agility, Growth, and Big Data Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Malik, M.S.; Ijaz, M.; Irfan, M. Employer responses to poaching on employee productivitmediating role of organizational agility in technology companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5369. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J. How the effects of IT and knowledge capability on organizational agility are contingent on environmental uncertainty and information intensity. Inf. Dev. 2015, 31, 358–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahoo, L.A.; Buriro, M.A.; Khan, S.A. Examining the Relationship of Knowledge Management with Organization Agility in General Administration of Libraries; Library Philosophy and Practice: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eshlaghy, A.; Mashayekhi, A.N.; Ghatari, A.; Razavian, M. Applying path analysis method in defining effective factors in organization agility. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2010, 48, 1765–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuna, O.K.; Arslan, F.M. Impact of the number of scale points on data characteristics and respondent’s evaluations: An experimental design approach using 5-point and 7-point Likert-type scaled. Istanb. Univ. Siyasal Bilgiler Fak. Derg. 2016, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.E.; Hufit, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jhantasana, C. Should a rule of thumb be used to calculate PLS-SEM sample size. Asia Soc. Issues 2023, 16, e254658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budiman, M.A.; Soetjipto, B.W.; Kusumastuti, R.D.; Wijayanto, S. Organizational agility, dynamic managerial capability, stakeholder management, discretion, and project success: Evidence from the upstream oil and gas sectors. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indonesian_Petroleum_Association. Leadership to Support Oil and Gas Sector Adaptation in the Era of Energy Transition. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipa.or.id/en/news/convention-and-exhibition/leadership-to-support-oil-and-gas-sector-adaptation-in-the-era-of-energy-transition (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Ajay Guru Dev, C.; Senthil Kumar, V.S.; Rajesh, G. Effective human utilization in an original equipment manufacturing (OEM) industry by the implementation of agile manufacturing: A POLCA approach. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2017, 27, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Perrons, R.K. How innovation and R&D happen in the upstream oil & gas industry: Insights from a global survey. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2014, 124, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Atiq, M.; Maurya, L. A Current study on the limitations of agile methods in industry using secure google forms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 78, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiak, A.; Dewicka, A. Application of selected quantitative analysis methods in the design of an ergonomic system. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 3, 4776–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, D.N.; Duarte, L.G.; Perico, I. Driving change in the oil and gas industry: A digital transformation framework. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 24–26 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rbeawi, S. A review of modern approaches of digitalization in oil and gas industry. Upstream Oil Gas Technol. 2023, 11, 100098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohari, U. Digitalization in the Oil and Gas Industry—A Mindset Change. 2020. Available online: https://jpt.spe.org/twa/digitalization-oil-and-gas-industry-mindset-change?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQjwu8uyBhC6ARIsAKwBGpRakjIEZErIy7-f7JoCj6M_q9Go5H3pVkOCIUL1CTSg2y_NTk4X4hsaArLVEALw_wcB (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Grant, R.M. The development of knowledge management in the oil and gas industry. Universia Bus. Rev. 2013, 40, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- David, R.M.; Gupta, D.S. Knowledge management in the oil and gas industry and its transformation in the industry 4.0 era. Migr. Lett. 2024, 21, 483–503. [Google Scholar]

- Umeteme, O.M.; Adegbite, W.M. Project leadership in the oil and gas industry: The case for path-goal leadership theory. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, W.; Timsard, S.; Liu, J.; Khamaksorn, A. Application of knowledge management in oil and gas projects: A systematic literature review. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Digital Arts, Media, and Technology (DAMT) and 7th ECTI Northern Section Conference on Electrical, Electronics, Computer and Telecommunications Engineering (NCON), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 31 January–3 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alagoz, E.; Alghawi, Y.; Ergul, M.S. Innovation in exploration and production: How technology is changing the oil and gas landscape. J. Energy Nat. Resour. 2023, 12, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description Cluster | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company production size (KBOEPD) | 0–100 KBOEPD | 49 | 47.6 | 47.6 |

| >100 KBOEPD | 54 | 52.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 103 | 100.0 | - | |

| Ownership | State-owned company | 71 | 68.9 | 68.9 |

| Private company | 32 | 31.1 | 31.1 | |

| Total | 103 | 100.0 | - | |

| Company establishment | Fewer than 10 years | 36 | 35.0 | 35.0 |

| 10–20 years | 54 | 52.4 | 87.4 | |

| Over 20 years | 13 | 12.6 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 103 | 100.0 | - | |

| Number of Full-time Employees | Fewer than 250 | 20 | 19.4 | 19.4 |

| 250–500 | 21 | 20.4 | 39.8 | |

| 500–750 | 43 | 41.7 | 81.6 | |

| Over 750 | 19 | 18.4 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 103 | 100.0 | - | |

| Operation Type | Onshore | 46 | 44.7 | 44.7 |

| Offshore | 27 | 26.2 | 70.9 | |

| Onshore & offshore | 30 | 29.1 | 100.0 | |

| Total | 103 | 100.0 | - | |

| Cluster | Characteristics | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Company production size (KBOEPD) | 0–100 KBOEPD >100 KBOEPD | 0.05 | No evidence of a difference between group |

| Ownership | State-owned company private company | 0.398 | No evidence of a difference between group |

| Company establishment | Fewer than 10 years 10–20 years Over 20 years | 0.306 | No evidence of a difference between group |

| Number of Full-time Employees | Fewer than 250 250–500 500–750 Over 750 | 0.461 | No evidence of a difference between group |

| Operation Type | Onshore Offshore Onshore & offshore | 0.511 | No evidence of a difference between group |

| Construct | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| IT competence | 0.947 | 0.953 | 0.648 |

| Digital platform capability (DPC) | 0.926 | 0.947 | 0.817 |

| IT Infrastructure (ITI) | 0.844 | 0.904 | 0.759 |

| Data analytics capabilities (DAC) | 0.906 | 0.932 | 0.774 |

| Innovation capacity | 0.950 | 0.955 | 0.661 |

| Innovation opportunity (IO) | 0.928 | 0.948 | 0.819 |

| Knowledge creation (KC) | 0.860 | 0.914 | 0.780 |

| Resources allocation (RA) | 0.914 | 0.937 | 0.788 |

| Human–Technology–Organization | 0.966 | 0.968 | 0.655 |

| Human skills & capabilities (HSC) | 0.893 | 0.924 | 0.754 |

| Technology adoption (TA) | 0.901 | 0.938 | 0.834 |

| Organizational structure & design (OSD) | 0.912 | 0.958 | 0.919 |

| Change management (CM) | 0.861 | 0.935 | 0.877 |

| Performance management (PM) | 0.922 | 0.942 | 0.803 |

| Leadership | 0.958 | 0.963 | 0.745 |

| Entrepreneurial orientation (ENT) | 0.940 | 0.971 | 0.943 |

| Adaptability (ADA) | 0.861 | 0.934 | 0.876 |

| Communication (COM) | 0.921 | 0.950 | 0.863 |

| Empowerment (EMP) | 0.834 | 0.923 | 0.857 |

| Knowledge management | 0.916 | 0.935 | 0.704 |

| Learning culture (LC) | 0.934 | 0.968 | 0.938 |

| Knowledge accessibility (KNO) | 0.869 | 0.939 | 0.884 |

| Knowledge transfer (KT) | 0.866 | 0.937 | 0.882 |

| Organizational agility | 0.961 | 0.969 | 0.863 |

| HTO | IT Competence | Innovation Capacity | Knowledge Management | Leadership | Organization Agility | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTO | 4.843 | |||||

| IT Competence | 3.782 | |||||

| Innovation Capacity | 3.413 | 4.515 | ||||

| Knowledge Management | 4.932 | 3.230 | 4.044 | |||

| Leadership | 4.673 | 4.928 | ||||

| Organization Agility |

| Relationship Between Variables in Model | Estimated Value | Standard Error | t-Value | p Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: HTO ➔ organizational agility | 0.403 | 0.167 | 2.414 | 0.016 | H1 strongly supported |

| H2: Leadership ➔ organizational agility | 0.265 | 0.114 | 2.314 | 0.021 | H2 strongly supported |

| H3: Knowledge management ➔ organizational agility | −0.011 | 0.107 | 0.102 | 0.919 | H3 rejected |

| H4: Innovation capacity ➔ organizational agility | 0.274 | 0.103 | 2.667 | 0.008 | H4 strongly supported |

| H5: IT competence ➔ organizational agility | 0.028 | 0.076 | 0.372 | 0.710 | H5 rejected |

| H6: Leadership ➔ HTO | 0.000 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.969 | H6 rejected |

| H7: Knowledge management ➔ HTO | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.067 | 0.947 | H7 rejected |

| H8: Knowledge management ➔ innovation capacity | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.750 | 0.454 | H8 rejected |

| H9: Innovation capacity ➔ IT competence | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 0.904 | H9 rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Putra, O.G.; Suzianti, A.; Yassierli. Enhancing Organizational Agility in Sustaining Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector: An Integrating Human-Technology-Organization Framework Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411346

Putra OG, Suzianti A, Yassierli. Enhancing Organizational Agility in Sustaining Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector: An Integrating Human-Technology-Organization Framework Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411346

Chicago/Turabian StylePutra, Octaviandy Giri, Amalia Suzianti, and Yassierli. 2025. "Enhancing Organizational Agility in Sustaining Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector: An Integrating Human-Technology-Organization Framework Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411346

APA StylePutra, O. G., Suzianti, A., & Yassierli. (2025). Enhancing Organizational Agility in Sustaining Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Sector: An Integrating Human-Technology-Organization Framework Perspective. Sustainability, 17(24), 11346. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411346