The Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS 26) program used structural equation modelling (SEM) to examine the relationships between big data, product innovation, agile supply chains, and knowledge management in pharmaceutical manufacturing companies. The study used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), a sophisticated statistical technique, which is employed to understand the factor structure of a dataset and test hypotheses about the relationships between observed data and the underlying constructs. This method makes it possible to analyse complex causal networks and also the simultaneous investigation of multiple interactions. To validate measurement scales, items with factor loadings of at least 0.50 were included, although our final model showed that the loadings for all retained items were substantially higher than 0.75.

4.2. Measurement Model

The research revolves around four major constructs that were derived from the questionnaire and tested hypotheses. Big data, as the first construct, was evaluated through 14 items that covered 4 aspects: volume, velocity, variety, and veracity. Each of these aspects reflected a particular big data in the implementation of the pharmaceutical organisations. Volume (4 items) was about the amount of data analysed, whereas velocity (4 items) concerned the speed of data processing. Variety (3 items) dealt with the number of data sources used, and veracity (3 items) was about the quality and reliability of the data being processed [

86].

The second construct, knowledge management, was represented by 12 items that were split into three dimensions: acquire, transfer, and distribute. Acquire (3 items) is an internal capacity of an organisation to recognise and acquire knowledge from both external and internal sources. Transfer (6 items) looked at the organisation’s internal processes of synthesising and distributing knowledge, and distribute (3 items) referred to the efficiency with which the information was shared with the external stakeholders [

89].

The third one, agile supply chain, was a construct that had 9 associated items. All of these items, in their totality, describe the flexibility, responsiveness, and adaptability of the pharmaceutical companies’ supply chain operations with respect to supplier relationships, capacity adjustments, and responding to customer demands [

88].

The fourth construct, product innovation, was represented by two different dimensions: radical product innovation and incremental product innovation, each comprising five items. Radical innovation items depicted radical changes to existing products (e.g., products that differ substantially, radical innovations introduced more frequently than competitors), whereas Incremental Innovation items showed minor enhancements of existing products (e.g., products that differ slightly, incremental improvements to existing lines) [

87]. The questionnaire is included in the

Appendix A to provide a detailed description of all measurement components.

For hypothesis testing, product innovation was considered as individual dimensions and a combined construct as well. Since the original hypotheses (H1, H3, H4, H6, H7) refer to “product innovation” as one concept, this dual approach allowed us to test both.

Firstly, the overall influence of the predictors on innovation, in general, could be examined. Secondly, their differential effects on different types of innovation could be investigated.

4.4. Assessment of Common Method Bias

Since all the data were gathered through self-reported questionnaires from the same individuals at a single point in time, we evaluated the possible common method bias (CMB) by multiple approaches that are suggested in the recent methodological literature.

Full Collinearity Assessment. At first, we performed a full collinearity test by calculating variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all latent constructs according to the approach suggested by [

93]. This test is considered to be more robust than Harman’s single-factor test in identifying common method variance in structural equation models. The VIF values were in the range of 1.90 to 2.92, with all of them staying well below the conservative threshold of 3.3. To be exact, the VIF values were big data (2.61), knowledge management (2.92), agile supply chain (2.51), and product innovation (1.90). The findings from this analysis suggest that common method variance is not a significant source of error in the results.

Harman’s Single-Factor Test. Secondly, we executed Harman’s single-factor test by loading all 45 measurement items onto a single factor in exploratory factor analysis. The first unrotated factor accounted for 38.9% of the total variance, which is considerably less than the 50% threshold proposed by [

94]. This result can also be considered as evidence that a single source of common method factor does not dominate the covariance of the measures. The agreement between both statistical tests (VIF < 3.3 and Harman’s test < 50%) reinforces the trust in the absence of a substantial common method bias.

Procedural Remedies. Thirdly, to lessen potential CMB ex ante, we took several procedural actions were taken during the data collection: (1) through clear statements on the cover page of the questionnaire, we assured respondents were assured of their complete anonymity and confidentiality, (2) by placing predictor variables (big data, knowledge management, agile supply chain) and criterion variables (product innovation) in different sections with intervening demographic questions, the variables were psychologically separated thus helping respondents see them as different constructs, (3) to reduce the possibility of different interpretations of the questions and the complexity of the questionnaire, we used clear and concise item wording was used that was validated during the pre-test with five pharmaceutical managers, and (4) where it was possible within dimensional subscales, the counterbalancing of the question order was applied to minimise consistency motifs.

The convergence of two independent statistical tests and multiple procedural controls gives us substantial assurance that common method bias is not a major factor that undermines the validity of our structural model results.

4.5. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

We built a structural model to evaluate the impact of big data on product innovation, with knowledge management and agile supply chain as possible mediators. In line with our predictions that regarded “product innovation” as a single construct, we constructed a combined measure by fusing both radical and incremental innovation for the initial hypothesis testing. Moreover, we conducted additional analyses to determine the influence of radical and incremental innovation separately to shed more detailed light on the phenomena.

The

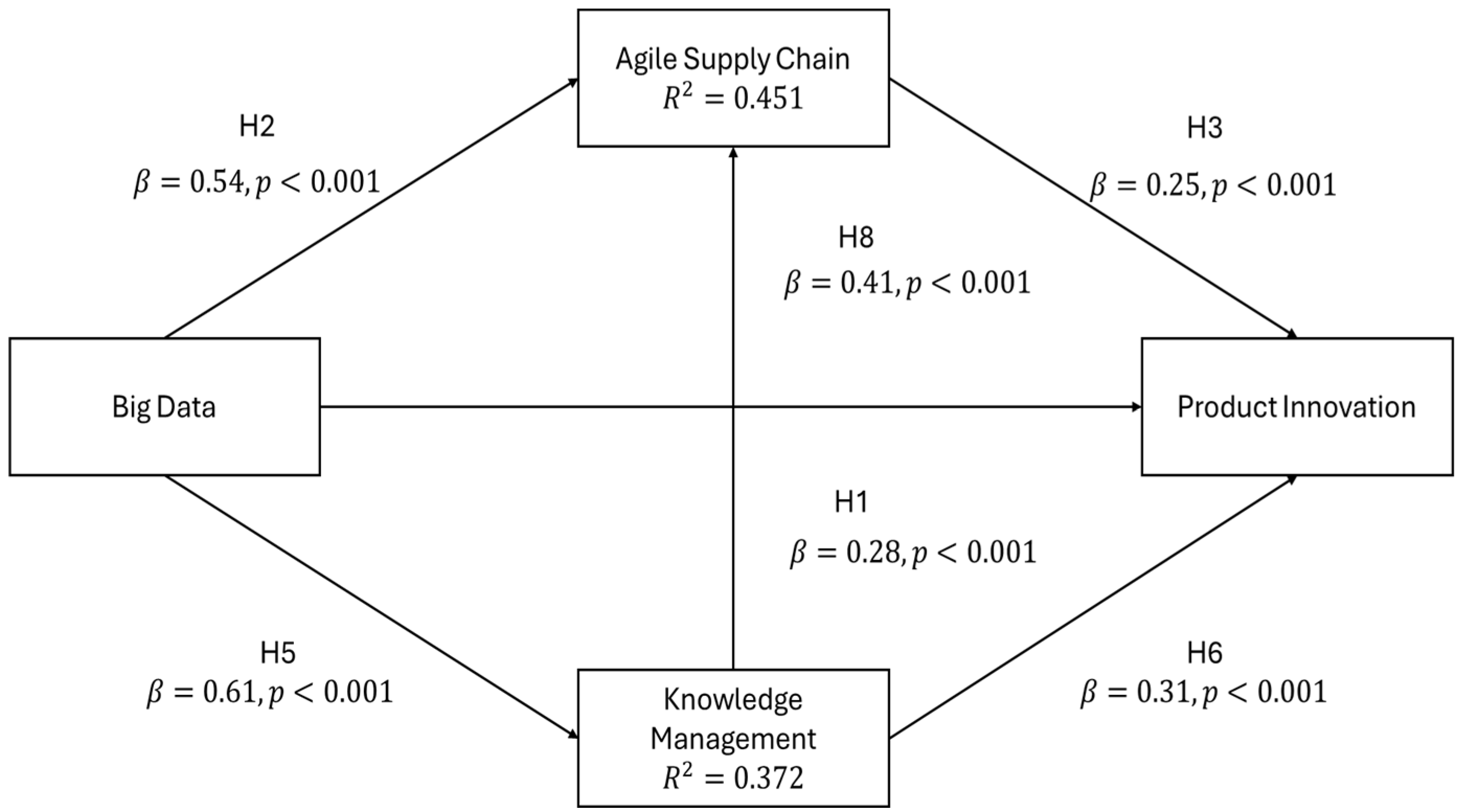

Table 6 shows that the results of the structural model support the confirmation of all hypothesised direct relationships. Big data has a very significant positive direct impact on product innovation (β = 0.28,

p < 0.001), knowledge management (β = 0.61,

p < 0.001), and an agile supply chain (β = 0.54,

p < 0.001). Knowledge management (β = 0.31,

p < 0.001) and an agile supply chain (β = 0.25,

p < 0.001) are both strongly positively correlated with product innovation. In addition, knowledge management has a positive effect on an agile supply chain (β = 0.41,

p < 0.001). None of the path coefficients is insignificant, as all the critical ratios (t-values) are far beyond the 1.96 threshold, providing strong evidence for the theoretical framework. The 95% bootstrap confidence intervals for all paths do not include zero, thus confirming the robust nature of the relationships.

In order to test the mediation hypotheses (H4 and H7), we used bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to generate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects. This was in line with the recommendations of [

95].

The

Table 7 shows that the examination of pathway contributions informed the researchers about the major changes that big data is making to product innovation. The direct pathway accounted for less than half (46.3%) of the total effect, whereas significant indirect influences were felt via two key organisational capabilities. Knowledge management was the main mediating mechanism, thereby explaining almost one-third (31.3%) of the total effect, while agile supply chain practices made up an additional 22.4%. The statistical strength of these results was verified by bootstrap confidence intervals that indicated the significance of all the pathways, as they did not include zero at the 95% confidence level.

This set of outcomes offers strong support for our mediation hypotheses, in particular, that both knowledge management capabilities (H7) and agile supply chain practices (H4) are the main sources of the intervening mechanisms by which big data capabilities lead to increased product innovation. The two mediating pathways, being complementary, imply that pharmaceutical companies have to develop not only the organisational knowledge infrastructure but also the operational supply chain flexibility in order to be able to fully exploit the innovation returns from big data investments.

4.6. Supplementary Analysis: Effects on Radical vs. Incremental Innovation

To grasp more clearly the different ways big data affects various innovation types, we examined the impacts of big data on radical and incremental product innovation separately. The findings showed that the positive effects of big data on radical innovation, as opposed to incremental innovation, were stronger and more consistent across all the channels.

The

Table 8 shows that the overall positive effect of big data on radical innovation was around 35.3% higher than its effect on incremental innovation (0.69 versus 0.51), which indicates that big data is of particular importance to disruptive innovations. The difference in the effect was very significant for the way through an agile supply chain (60% more for radical innovation), which suggests that supply chain flexibility may be especially necessary for breakthrough innovations that require a rapid reconfiguration of resources and processes. The way through knowledge management revealed more balanced effects (29.4% more for radical innovation), which implies that knowledge capabilities support both innovation types almost to the same extent. These results carry significant strategic implications: pharmaceutical companies looking for breakthrough innovations should focus on big data velocity and supply chain agility, while companies that are only interested in continuous improvement can obtain good results with moderate investments in these capabilities.

The

Table 9 shows the theoretical framework explains the majority of the variance for all the key constructs and thus can be said to have strong explanatory power. In the case of product innovation overall, the model accounts for 43.5% of the variance, meaning that the combination of big data capabilities, knowledge management practices, and agile supply chain processes explains a large part of the variation in pharmaceutical companies’ innovation outcomes. This R

2 value is regarded as quite substantial in the field of organisational research, where R

2 values above 0.33 are generally considered to indicate strong explanatory power [

96].

Analysing the different innovation types separately, the model has more explanatory power for radical innovation (47.2%) than for incremental innovation (37.6%), the difference being 9.6 percentage points. The pattern is consistent with the conclusion that big data and related mechanisms have far more impact on radical innovations than on incremental ones, probably because radical innovations obtain more pattern recognition and prediction capabilities from big data analytics.

Regarding knowledge management, the variance accounted for (37.2%) indicates that the implementation of big data is a major driver of the knowledge management capabilities of pharmaceutical companies, while other factors not included in the model (e.g., organisational culture, leadership support, IT infrastructure) should be considered as well. In the case of an agile supply chain, the model captures 45.1% of the variance, indicating that the interplay between big data and knowledge management is responsible for almost half of the changes in supply chain agility. The relatively high R2 for the agile supply chain (0.451) as compared to knowledge management (0.372) implies that these constructs are especially powerful in predicting supply chain flexibility.

Theoretically, the R2 values are a testament to the soundness of the framework and emphasise that big data is a key enabler of innovation, not only by direct impact but also through mediating mechanisms, in the Jordanian pharmaceutical industry. The levels of explained variance are either at the same level as or higher than those reported in the studies on innovation antecedents conducted in pharmaceutical and manufacturing contexts.

4.7. Summary of Hypothesis Testing

All eight hypotheses were substantiated by the data collected from the field, which is in line with the theoretical framework that was set up. H1, the hypothesis that big data would have a positive impact on product innovation, was corroborated with a substantially positive direct effect (β = 0.28, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.40]). This direct effect is responsible for 46.3% of the overall impact of big data on innovation, which means that the data analytics capabilities are a source of innovation even if the mediating mechanisms are not perfect.

H2, a statement that big data has a positive effect on agile supply chain, was confirmed with a high degree of certainty (β = 0.54, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.42, 0.66]). The model shows that this is the second-strongest path, thus indicating that data-driven insights have a major role in enhancing the supply chain responsiveness. The findings of H3 indicate that there is a positive link between the agile supply chain and product innovation (β = 0.25, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.13, 0.37]), thus implying that operational flexibility can be converted into innovation outcomes. H4, a statement that agile supply chain is a mediator in the relationship between big data and product innovation, was corroborated with a significant indirect effect of 0.14 (95% CI [0.08, 0.19], p = 0.002), which represents 22.4% of the total effect.

H5, a claim that big data has a positive effect on knowledge management, was supported with a high degree of confidence, as it was the path with the largest coefficient in the model (β = 0.61, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.49, 0.73]). The establishment of such a strong link indicates that big data is the main source of organisational knowledge capabilities. H6 substantiated the positive link between knowledge management and product innovation (β = 0.31, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.18, 0.44]), which means that knowledge infrastructure is a direct facilitator of innovation. H7, a statement that knowledge management is a mediator in the relationship between big data and product innovation, was corroborated with a significant indirect effect of 0.19 (95% CI [0.12, 0.26], p < 0.001), representing the most substantial mediating pathway at 31.3% of the total effect. Lastly, H8 established a positive dependency between knowledge management and the agile supply chain (β = 0.41, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.53]), implying that knowledge capabilities facilitate organisational flexibility.

The results show that big data in the pharmaceutical industries in Jordan has been a driving force behind product innovations through direct and indirect routes. There is a partial mediation in the relationship between big data and product innovation through two factors, i.e., agile supply chain practices (H4, which contributes to 22.4% of the total effect) and knowledge management capabilities (H7, which contributes to 31.3% of the total effect), with the direct effect making up the remaining 46.3%. The simultaneous development of these two capabilities, i.e., knowledge management and agile supply chain, would thus be the best strategy of pharmaceutical firms to maximise the innovation dividend coming from big data investments.

Moreover, additional analysis showed that the role of big data in radical innovation was much more prominent than in incremental innovation, with the overall effects for breakthrough innovations being 35.3% higher. The difference was especially noticeable through the agile supply chain channel (60% stronger for radical innovation), thereby indicating that supply chain agility is particularly necessary for transformative innovations that require a quick reconfiguration of the resource base. All the relationships were positive and statistically significant, thus lending support to the theoretical framework, which holds that big data, if effectively used through efficient knowledge management and agile supply chain, will significantly increase pharmaceutical companies’ capabilities to innovate, especially in the case of transformative innovations that require a considerable deviation from existing products.

The R2 values give an account of the proportion of explained variance in the endogenous constructs. The indices serving as model fit demonstrate that the data fit perfectly: χ2/df = 2.17 (threshold < 3.0), CFI = 0.93 (threshold > 0.90), TLI = 0.92 (threshold > 0.90), RMSEA = 0.055 with 90% CI [0.048, 0.062] (threshold < 0.08), and SRMR = 0.048 (threshold < 0.08). The 5000 times bootstrap confidence intervals are used for the robust estimates of the parameter stability.

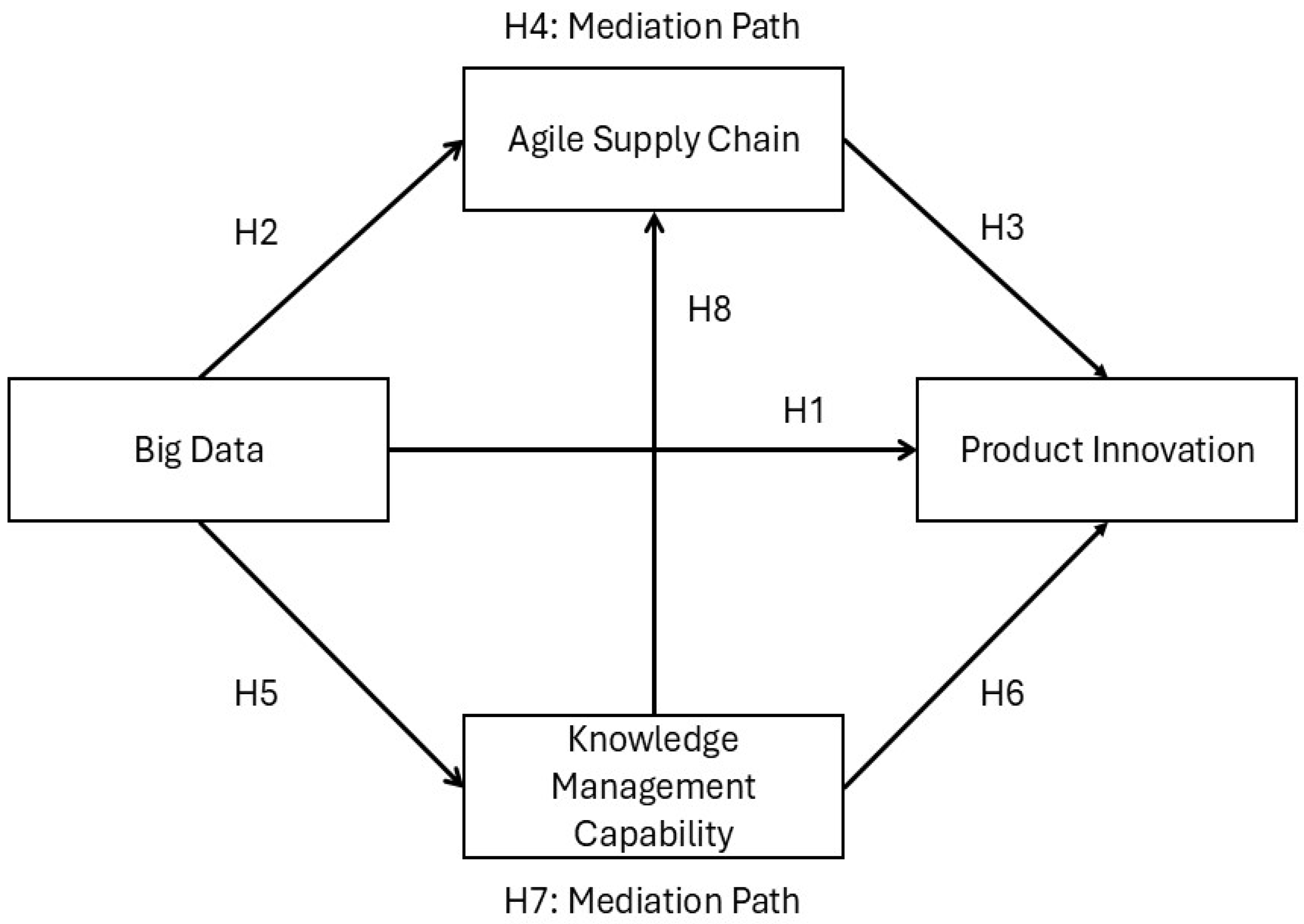

Figure 2 shows the structural equation model highlighting multiple routes that allow big data to have an impact on product innovation. In fact, the research uncovers that there exist, on the one hand, direct influences (big data directly enabling the innovation through improved analytical capabilities), and on the other, indirect influences, which are mediated via organisational capabilities.

The first indirect route is through knowledge management, where big data makes the firm proficient in acquiring, transferring, and distributing knowledge (β = 0.61) and, then, consequently, the organisation innovates in product development (β = 0.31); therefore, the indirect effect accounts for 0.19.

The second indirect route happens through the agile supply chain, where big data brings about supply chain flexibility and responsiveness (β = 0.54) that, in their turn, support innovation outcomes (β = 0.25) and, thereby, the indirect effect amounts to 0.14.

Moreover, a consecutive path is available through which big data empowers knowledge management (β = 0.61); thereafter, the agile supply chain capabilities are (β = 0.41), and, finally, the product innovation (β = 0.25) is getting credit. The intricate pattern of direct and indirect effects reflected in the study is consistent with the idea that data-driven innovation is a multi-layered process in pharmaceutical organisations.

The levels of variance that have been accounted for serve as proof of the model’s explanatory power. Product innovation (R2 = 0.435) is an example where the fusion of big data, knowledge management, and agile supply chain explains most of the variation in innovation outcomes.

Knowledge management (R2 = 0.372) indicates that big data capabilities are the key factor that leads to the development of the organisation’s knowledge infrastructure.

Agile supply chain (R2 = 0.451) points out that big data, together with knowledge management, explains nearly half of the changes in supply chain flexibility.

The difference in explanatory power for radical innovation (R2 = 0.472) as opposed to incremental innovation (R2 = 0.376) is an additional piece of evidence that the model is especially good at breakthrough innovations, which is in line with the theoretical expectation that big data analytics are particularly helpful in spotting patterns that lead to transformative rather than just incremental advances.