1. Introduction

The ornamental nursery industry is a thriving agricultural sector of significant economic and landscape value worldwide [

1,

2].

However, in Europe, its competitiveness is increasingly being challenged by rising production costs, largely due to higher prices of raw materials such as peat and energy [

3].

In Italy, it is recognized as a center of excellence, with production exceeding 3 billion euros in value [

4]. As urbanization advances and the focus on public and private green spaces increases, demand for ornamental potted plants continues to grow. Beyond their esthetic and economic value, ornamental potted plants are increasingly important in creating restorative and therapeutic green spaces, including green roofs, healing gardens, and indoor horticultural settings. These applications have been shown to support psychological well-being, aid recovery, and improve the quality of life in healthcare environments [

5,

6]. These emerging uses highlight the growing social relevance of high-quality ornamental plants and further reinforce the need for sustainable growing media that reduce the environmental footprint of their production.

This, in turn, demands high-performance growing media (GM) that can support the cultivation of top-quality plants [

7]. GM are defined as tailor-made substrates formulated to provide the physical support, water–air balance, and nutrient availability required for optimal root development and plant performance.

The performance of potted plants relies on selecting the appropriate GM. Peat has long been the preferred organic GM because of its excellent water retention, air porosity, and chemical stability [

8,

9,

10]. Worldwide, about 10.3 million tons—equivalent to 41 million m

3—of peat are mined each year for the production of horticultural growth medium [

11]. In China, production and sales of both imported and domestic peat have increased by 40% annually since 2015, reaching 4 million m

3 in sales by the end of 2021, with projections of reaching 50 million m

3 over the next decade [

12].

However, this resource, obtained from peat bogs that formed over millennia, is widely regarded as unsustainable because degraded peatlands release greenhouse gases, contributing to roughly 25% of all CO

2 emissions from the land-use sector [

13]. Additionally, peat extraction results in the destruction of moorlands, which are habitats for rare animal and plant species, and depletes some of the largest organic carbon reserves found in terrestrial ecosystems [

14,

15].

The environmental impact of peat is further increased by the long transport distances between extraction sites and ornamental plant production facilities [

16]. Hashemi et al. [

17] have demonstrated that, compared to alternative GM, peat is one of the main contributors to the carbon footprint over the entire life cycle of ornamentals: the Global Warming Potential of all peat alternatives was significantly lower than peat, ranging from 89% to 109%. In recent years, the discussion around peat use has also gained relevance at the policy level. Several European countries have introduced restrictions or phase-out strategies for peat in horticulture, driven by climate mitigation goals and the protection of peatland ecosystems [

18,

19]. This evolving regulatory framework further emphasizes the need to identify reliable and sustainable alternatives that can be adopted in nursery production without compromising crop quality or operational feasibility.

Therefore, when choosing a new GM, environmental factors are as important as agronomic and economic performance [

20,

21,

22]. In this context, the principle of circular economy (CE) emerges as a crucial paradigm for promoting more sustainable agriculture. CE aims to convert what was traditionally seen as ‘waste’ into valuable resources, thereby reducing waste, decreasing reliance on virgin raw materials, and establishing sustainable material cycles [

23]. Forestry and agro-industrial by-products, which are often plentiful and costly to dispose of, have substantial potential for valorization as innovative GM components [

24].

To ensure the sustainability of new agricultural solutions, it is essential to implement the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), a standardized method (ISO 14040/44) which evaluates the environmental impacts of a product or service throughout its entire lifespan—from ‘cradle to grave’ [

25]. LCA is vital for identifying environmental hotspots, balancing trade-offs between impact categories, and guiding efforts to minimize production impacts [

26,

27,

28]. By collecting inputs and outputs in the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) and assessing potential environmental impacts, LCA serves as a valuable tool for understanding differences among various production processes [

29].

Despite the growing interest in peat substitutes in horticulture, most current research tends to focus on either agronomic performance or environmental impact, often neglecting a comprehensive assessment that considers economic sustainability and eco-efficiency.

In agriculture, eco-efficiency involves optimizing the use of resources to produce crops while minimizing environmental impact. This concept is becoming increasingly important in tackling global challenges such as climate change and biodiversity loss.

There is also a lack of LCA studies [

30,

31,

32] applied to by-products, such as wood fiber (WF), coffee silverskin (CS), and brewers’ spent grain (BSG), which are used as partial peat replacements in soilless GM. These by-products, originating from the forestry and beverage industries, are locally available, low-cost materials that support the principles of CE.

Based on the above, this study could fill this gap by evaluating the use of such by-products compared to peat through a comprehensive approach that combines environmental assessment via the LCA methodology with eco-efficiency. In addition, the transition towards alternative growing media also involves practical aspects that are relevant for nursery production. Besides environmental and economic performance, growers often consider factors such as the regularity of supply, the consistency of material quality, and how easily a new substrate can be integrated into existing greenhouse routines. Including these elements in the background of the study helps to frame peat substitution as not only a technical comparison but also a change that must fit within real production systems [

33]. The aim is to provide new insights into the environmental and economic sustainability of these innovative GM.

The research question guiding this study is the following: which by-product (WF, CS, or BSG) and what percentages of peat replacement provide the best eco-efficiency with regard to environmental and economic sustainability in potted ornamental sage cultivation?

2. Materials and Methods

The environmental impact of ten potted sage production techniques was evaluated by modeling ten scenarios linked to ten different GMs. These included increased doses ranging from 0 to 40% v/v of peat replacement (PR) for each alternative by-product: wood fiber (WF), coffee silverskin (CS), and brewers spent grain (BSG).

The GMs were identified as follows: 0PR (100% peat), WF10 (90% peat + 10% WF), WF20 (80% peat + 20% WF), WF40 (60% peat + 40% WF), CS10 (90% peat + 10% CS), CS20 (80% peat + 20% CS), CS40 (60% peat + 40% CS), BSG10 (90% peat + 10% BSG), BSG20 (80% peat + 20% BSG), and BSG40 (60% peat + 40% BSG). All scenarios were modeled under the same cultivation conditions. Irrigation plant handling and general management were kept constant so that any differences in the results could be directly attributed to the composition of the GM. This approach reflects a common situation in nursery production, where growers tend to adjust the substrate formulation without modifying the rest of the cultivation protocol.

2.1. Materials

Salvia ‘Amistad’ plants were used in this study. Salvia ‘Amistad’ is a hybrid cultivar believed to be a cross between S. guaranitica Speg. (anise-scented sage) and S. gesneriiflora Lindl. & Paxton (Mexican scarlet sage). It was discovered in Argentina by Rolando Uria, a renowned Salvia specialist, and is commonly called the friendship sage, with its Spanish name ‘Amistad’ also meaning ‘friendship’. Reaching 1.2 m in height quickly, this long-lasting perennial produces tall spires of deep purple flowers above fragrant foliage; the tubular blooms burst from almost black buds throughout summer and autumn.

The production of the potted ‘Amistad’ ornamental sage (Lamiaceae family) took place on an ornamental farm situated in Monopoli (Bari, Italy, 40°54′19.1′′ N, 17°18′21.4′′ E; 66 m above sea level), under typical Mediterranean climatic conditions. The nine-month crop cycle was conducted in an unheated greenhouse and was monitored until the plants reached marketable quality, from September 2023 to June 2024. At transplanting (16 September 2023), young ‘Amistad’ plants were placed into recycled plastic pots measuring 14 cm in diameter and with a volume of 1.2 L The cultivation was performed in an unheated, naturally lit greenhouse covered with EVA film, located in Monopoli (Bari, Italy). According to the local meteorological station, average monthly outdoor temperatures ranged from 25 to 26 °C (max) and 18 to 20 °C (min) in September to approximately 27 °C (max) and 20 °C (min) in June. Irrigation was delivered through one pressure-compensated dripper per pot (2 L h−1), using water with an electrical conductivity of 0.45–0.65 dS m−1 and pH 6.3–6.5. The frequency and duration of irrigation were controlled by a timer and adjusted according to weather conditions to replenish substrate moisture losses and restore the weight of the pot. Agronomic inputs included irrigation, fertilizers, plant protection products (insecticides and fungicides in both liquid and solid formulations), adjuvants, and biostimulants in both liquid and granular forms.

Irrigation was managed using a drip system connected to an on-site well and applied in accordance with good agricultural practices. Fertirrigation was carried out weekly using water-soluble fertilizers, including various NPK formulations and micronutrients. The inventories, containing a detailed list of all the plastics and the amounts used in cultivation, are provided in

Appendix A (

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4,

Table A5,

Table A6,

Table A7,

Table A8,

Table A9 and

Table A10).

The irrigation water volume was 562.5 m3/ha, and the estimated energy use was 14,000 kWh/ha, based on data provided by the agronomist responsible for the farm.

The nature of plant protection products justifies such a comprehensive phytosanitary program: ornamental plants must be of impeccable esthetic and sanitary quality to be commercially viable. Even minor flaws in foliage or irregular growth patterns can compromise marketability, making effective pest and disease control essential to maintaining product uniformity and visual appeal.

2.2. Methodology

The system boundaries include all processes involved in sage production, from the greenhouse to the cultivation inputs (such as GM, fertilizers, pesticides, soil mulch film, recycled plastic pots, irrigation water, and energy use) throughout the growing cycle, until the plants are ready for market. The system includes all operations and inputs needed to produce ornamental sage plants meeting commercial standards, from transplanted seedlings onwards. The functional unit for this study is one hectare of greenhouse cultivation, equivalent to 90,000 pots of ‘Amistad’ sage.

Local drink industry companies (Brunocaffè and Birra Peroni, Bari, Italy) provided primary data for LCI on CS and BSG production processes. These data underwent an LCA analysis; the allocation of total impacts was based on the economic values of both CS and BSG, with 99% of the total impact attributed to the main products (roasted coffee and filtered beer) and the remaining 1% attributed to the two co-products. This method was preferred over other allocation methods (e.g., mass allocation or system expansion) because it was considered more appropriate to the reality of the case study, although applying another method would have led to more complex results. An experienced local farmer collected data on sage production.

Secondary LCI data for peat and WF are sourced from the Ecoinvent 5 database [

34] and from several databases used in the analysis.

The impact assessment was carried out using the software SimaPro 10.2.0.1. The evaluation methods employed were EPD 2018 (Environmental Product Declarations). The EPD is based on the ISO 14025 standard for conducting a type III environmental declaration [

35,

36]. Type III labels are found on LCA and report multiple environmental impacts [

37].

The used EPD method concentrated on eight impact categories that evaluate the main potential environmental impacts: Global Warming Potential (GWP) over 100 years, expressed in kg CO

2 eq.; ozone layer depletion (OLD), expressed in kg CFC

−11 eq.; Eutrophication (EU), expressed in kg

eq.; Acidification (AC), expressed in kg SO

2 eq.; photochemical oxidation (PO), expressed in kg NMVOC; Abiotic Depletion Elements (ADe), expressed in kg Sb eq.; Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels (ADff), expressed in MJ; and water scarcity (WS), expressed in m

3 eq. [

38].

These environmental considerations provide the context in which the economic performance of the different GM formulations can be better understood.

Regarding the economic aspect, we evaluated revenue, assuming that the ten scenarios (GM) exhibited different production responses in terms of shoot dry weight (g) in ‘Amistad’ sage. Notably, the 0PR and the three PR10 scenarios (WF10, CS10, and BSG10) showed similar mean values, ranging from 12.5 to 13.8 g, with limited yield differences compared to the control (12.4 g).The average shoot dry weight increased more significantly at 20% PR, reaching 13.5 g (WF20), 16.5 g (CS20), and 19.5 g (BSG20), while the 40% PR produced the highest yields, with 13.5 g (WF40), 19.8 g (CS40), and 20.0 g (BSG40), as shown in

Appendix A,

Table A11.

The production improvements of ‘Amistad’ in the different GM justify applying different market prices: EUR 3.50 for peat (0PR) and for 10% PR (WF10, CS10, BSG10); EUR 3.60 for WF20, EUR 3.70 for CS20, and EUR 4.00 for BSG20; and for 40% PR, EUR 3.60 for WF40, as well as EUR 4.00 for both CS40 and BSG40. This generates different revenue levels.

Eco-efficiency is increasingly regarded as a vital tool for inducing fundamental changes in the way societies generate and utilize resources, thus serving as a gauge of progress towards sustainability [

39]. From an operational perspective, eco-efficiency can be defined as the ratio of value added to the environmental impact involved. Consequently, enhancements in eco-efficiency can stem from improved economic performance, reduced environmental impacts, or a combination of both [

40].

In our study, the eco-efficiency indicator was calculated as the ratio of the costs of environmental impact resulting from the different energy consumptions (EUR) to the related revenues (EUR). This indicator highlights the influence of the economic value of each impact category on economic performance: the smaller the ratio, the higher the efficiency.

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Loads of the Production Process of By-Products

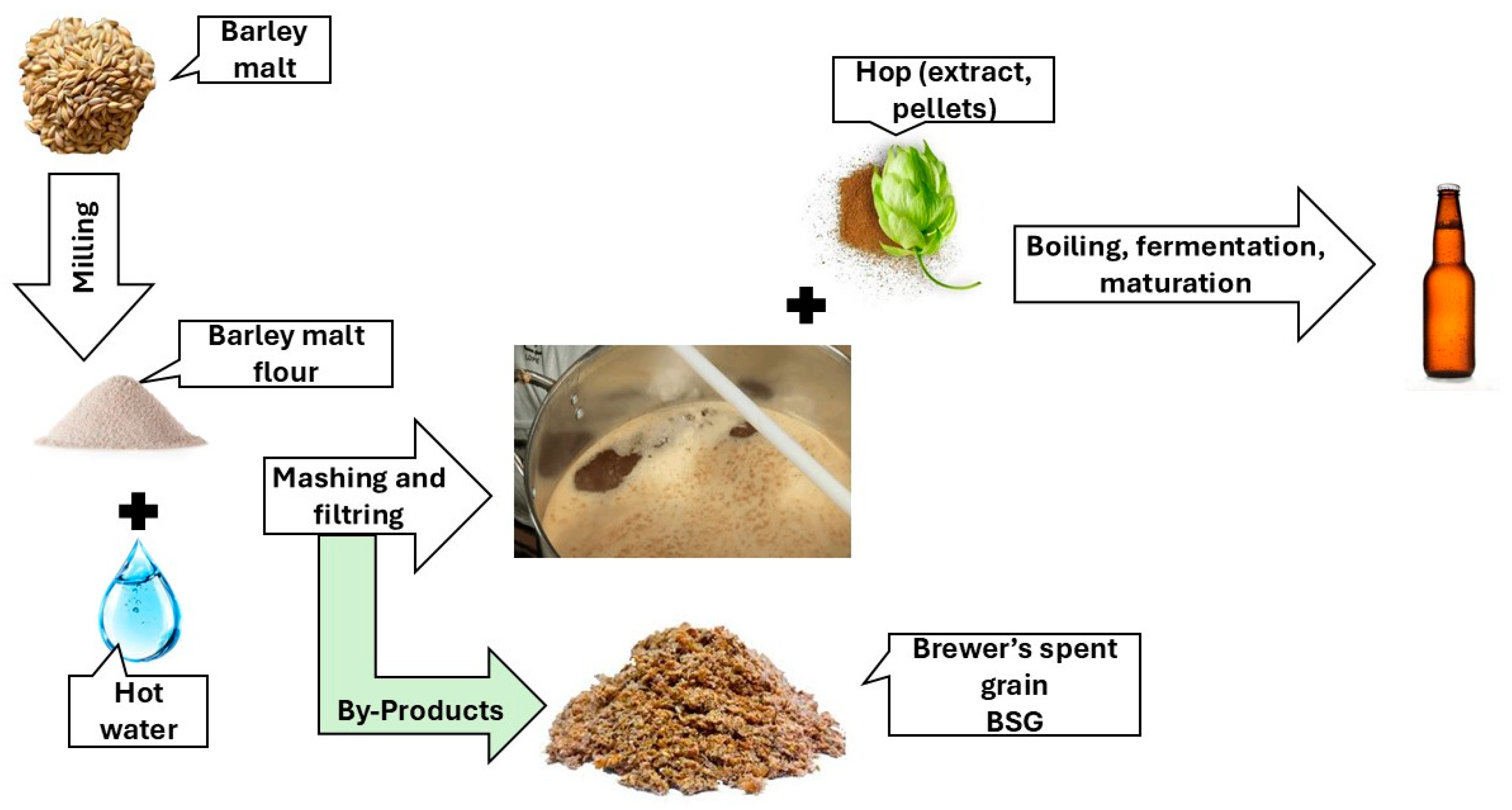

Wood fiber (WF) is produced by the wood industry from industrial residues and processing by-products through shredding, bleaching, drying, and sieving to obtain uniform particles suitable for growing media. Coffee silverskin (CS) is a by-product of the drink industry, generated during the roasting and grinding of coffee beans: the outer husks are separated, collected, and dried, retaining physicochemical properties suitable for GM use. Brewers’ spent grain (BSG), also from the drink industry, is derived from the processing of barley and other cereals in beer production. The solid residues from the wort are collected and sometimes dried and milled before being used as organic material in horticultural GM. The production processes of CS and BSG, as well as the related LCA of coffee and beer production with the consequent allocation of impacts to the by-products, are illustrated in

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 in

Appendix A.

3.2. LCA of the Sage’s Production Process

The impact assessment showed small differences among GM in most categories, except for Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels (see

Table 1). Acidification values were highly consistent, ranging from 0.0138 kg SO

2 eq (BSG20, BSG40) to 0.0139 kg SO

2 eq (0PR, WF10, WF20, WF40, CS10, CS20, CS40, BSG10). Eutrophication values varied slightly, ranging from 0.0029 kg

eq (BSG40) to 0.0031 kg

eq (CS40), with all other treatments reporting a value of 0.0030 kg

eq. Global Warming Potential (GWP100a) values ranged from 3.6138 kg CO

2 eq (BSG40) to 3.6425 kg CO

2 eq (0PR), with WF GM showing intermediate values of 3.6262 kg CO

2 eq (WF40), 3.6343 kg CO

2 eq (WF20), and 3.6384 kg CO

2 eq (WF10). CS ranged from 3.6374 kg CO

2 eq (CS40) to 3.6412 kg CO

2 eq (CS10), while BSG showed 3.6281 kg CO

2 eq (BSG20) and 3.6353 kg CO

2 eq (BSG10).

Photochemical oxidation potential ranged from 0.0119 kg NMVOCs (BSG20, BSG40) to 0.0121 kg NMVOC (WF40), with most GM, including CS and 0PR (peat), recording 0.0120 kg of NMVOCs.

More noticeable differences were seen in the Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels, with values ranging from 91.763 MJ (BSG40) to 96.889 MJ (0PR). In this category, the values for WF GM reached 91.9328 MJ (WF40), 94.410 MJ (WF20), and 95.6499 MJ (WF10); CS recorded 91.903 MJ (CS40), 94.396 MJ (CS20), and 95.6426 MJ (CS10). BSG showed the lowest values at each substitution level, ranging from 91.763 MJ (BSG40) to 95.6076 MJ (BSG10). The gradual reduction in fossil fuel use was associated with increasing levels of peat substitution, with effects already visible at 10% replacement and becoming more significant at higher replacement levels.

For water scarcity, the values ranged from 4.1627 m

3 eq (BSG40) to 4.1806 m

3 eq (0PR), with WF GM scoring from 4.1630 m

3 eq (WF40) to 4.1762 m

3 eq (WF10), CS from 4.1701 m

3 eq (CS40) to 4.1779 m

3 eq (CS10), and brewers’ spent grain from 4.1627 m

3 eq (BSG40) to 4.1761 m

3 eq (BSG10). Replacing peat was also linked to a gradual reduction in impact in this case, although differences remained modest. The LCA tables for the individual scenarios are shown in

Appendix A,

Table A12,

Table A13,

Table A14,

Table A15,

Table A16,

Table A17,

Table A18,

Table A19,

Table A20 and

Table A21.

Overall, the LCA results show that the environmental profiles of the ten GM formulations remain broadly similar across most impact categories, with only limited variation attributable to substrate composition. The most evident and consistent trend concerns the progressive reduction in the Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels (ADff) as peat is replaced by WF, CS, or BSG. BSG40 achieved the lowest value. This indicates that the choice of substrate primarily affects fossil resource use, while the impact of fertilizers, plastics, and energy inputs dominates the other categories.

3.3. Eco-Efficiency

The analysis of eco-efficiency in the Abiotic depletion of Fossil Fuels impact category revealed differences among the various GM (0PR, BSG10, CS10, WF10, BSG20, CS20, WF20, BSG40, CS40, WF40) in terms of fossil resource use, energy costs, and related revenues (

Table 2). Abiotic Depletion values ranged from 91.763 MJ (BSG40) to 96.889 MJ (0PR). GM with 40% peat replacement showed the lowest values (BSG40: 91.763 MJ; CS40: 91.903 MJ; WF40: 91.933 MJ), indicating reduced fossil fuel consumption compared with the peat-based control.

Using a conversion factor of 0.28 to convert MJ into kWh, energy consumption ranged from 25.694 kWh (BSG40) to 27.129 kWh (0PR). The corresponding energy costs, calculated at EUR 0.16/kWh [

41], ranged from EUR 4.111 (BSG40) to EUR 4.341 (0PR). GM with higher peat replacement percentages therefore exhibited the lowest energy costs, confirming a correlation between peat reduction and lower demand for fossil resources.

Revenues, calculated for nine plants per m2, varied according to the unit price assigned to each treatment. GM with 40% peat replacement showed unit prices of EUR 4.00/plant for BSG40 and CS40 and EUR 3.60/plant for WF40. This resulted in total revenues of EUR 36.00/m2, EUR 36.00/m2, and EUR 32.40/m2, respectively. For 20% peat replacement, the unit prices were EUR 4.00/plant (BSG20), EUR 3.70/plant (CS20), and EUR 3.60/plant (WF20), corresponding to total revenues of EUR 36.00/m2, EUR 33.30/m2, and EUR 32.40/m2. Treatments with 10% peat replacement (BSG10, CS10, WF10) and the peat control (0PR) were both priced at EUR 3.50/plant, yielding total revenues of EUR 31.50/m2.

The eco-efficiency ratio, calculated as the energy cost (EUR) divided by the revenue (EUR), ranged from 11.4% (BSG40 and CS40) to 13.8% (0PR). Intermediate values were observed for the other treatments: 12.7% for WF40, 11.7–12.7% for 20% peat replacement, and 13.2% for 10% peat replacement. These results indicate that increasing peat substitution reduces energy costs and fossil fuel consumption while maintaining balanced eco-efficiency across the tested GM.

Eco-efficiency analysis confirms this pattern: scenarios with higher level of peat replacement consistently show lower energy-related costs and improved revenue performance. Among these scenarios, BSG40 and CS40 provide the most favorable balance between reduced demand for fossil resource and economic returns, while the peat control exhibits the lowest efficiency.

4. Discussion

The LCA of cultivating potted ornamental sage with peat as a standalone organic GM indicates that, although environmental impacts are distributed across fertilizers, plastics, and energy, the most significant category is Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels (ADff). This is primarily because peat, the main organic component, being a fossil resource [

42], greatly contributes to the depletion of non-renewable resources and greenhouse gas emissions. Peat extraction leads to the degradation of peatland ecosystems and to the release of large amounts of CO

2, with greenhouse gas emissions comparable to those of fossil fuels, as noted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [

43], thereby accelerating climate change. ADff reflects an intrinsic property of peat: its link with fossil resource extraction. For this reason, even small reductions in peat content generate a significant decrease in this indicator, regardless of short-term variation in greenhouse operations. This explains why scenarios with higher shares of by-products consistently show lower values.

Therefore, partial replacement of peat is essential for reducing the environmental footprint of nursery production systems. In this regard, this study evaluated the use of three locally available organic by-products—wood fiber (WF), coffee silverskin (CS), and brewers’ spent grain (BSG)—as partial peat substitutes at levels of 10, 20, and 40%. Our results show that increasing the replacement rate leads to a gradual decline in ADff, with improvements already noticeable at 10% and more significant at 40%. Among the tested materials, BSG performed best, followed by CS and WF. In all cases, utilizing these by-products offers a dual benefit: decreasing reliance on fossil resources and enhancing the valorization of agro-industrial residues in line with circular economy principles. Regarding the other impact categories (Acidification, Eutrophication, Global Warming Potential, and water scarcity), differences among treatments were minor, confirming that baseline agronomic inputs tend to dominate the overall environmental profile. Nevertheless, peat remains a major contributor to ADff, making this category especially important in environmental assessments. This outcome reflects the considerable contribution of background inputs—plastics, fertilizers, and irrigation-related energy—which largely shape the footprint of greenhouse cultivation [

44]. Under this configuration, changes in substrate composition generate a comparatively smaller signal in most indicators, while the specific fossil resource nature of peat makes ADff more sensitive to replacement. The dominance of fertilizers, plastics, and energy inputs creates a substantial background footprint that dampens the relative influence of GM composition on categories such as GWP. As a result, peat’s distinct environmental burden emerges most clearly in the Abiotic Depletion of Fossil Fuels, reflecting its classification as a fossil resource and its extraction-related emissions. Based on this environmental framework, the economic assessment helps to clarify how substrate choices affect production costs and overall efficiency.

The eco-efficiency analysis, which combines the results of the analysis of the environmental impact and the economic performances analysis, further supports the advantages of alternative GM use (

Table 2). The updated results, which consider different plant prices and revenues, show that higher performances of peat replacement (20% and 40%) result in lower energy replacement costs and higher economic returns. Specifically, GM with 40% peat replacement (achieving the lowest eco-efficiency ratios, ≈11.4%) reflects reduced energy replacement costs (EUR 4.11–4.12) and increased revenues (EUR 36.00/m

2). WF40 also performed well (≈12.7%), with slightly lower revenues (EUR 32.40/m

2). Intermediate replacement levels (20%) display balanced values, ranging from 11.7% to 12.7%, while 10% replacement treatments and the peat control (0PR) recorded the highest ratios (≈13.2–13.8%), indicating lower overall economic and environmental performance. These findings confirm that increasing the substitution rate enhances both environmental and economic outcomes, with BSG 40 identified as the most efficient option.

Figure 1 shows the comparison between the revenue (green columns) and eco-efficiency indicator (red columns) for the different GMs by considering the percentage variation, in relation to the baseline (0PR), of revenue (dashed blue line) and eco-efficiency (continuous blue line). Notably, the highest peat replacements (40%) show the best performance both for the revenues and eco-efficiency, except for WF40. This is confirmed by the strong percentage variation in both revenue and eco-efficiency (+14.3% and −17.13%, respectively). On the contrary, peat replacements of 10% show weak performance for the eco-efficiency (−1.3%) and no revenue performances.

Nonetheless, the practical application of these by-products also hinges on their availability and current utilization [

45]. WF is already commercialized and adopted within the nursery sector [

46,

47], ensuring a well-established supply chain. CS remains an underutilized by-product, mainly destined for disposal, thus offering considerable potential for circularity. Although BSG exibits the most favorable environmental results, it is already widely used as livestock feed [

48,

49]. Therefore, when considering their utilization in GM, the competition with this well-established purpose must be taken into account, as well as the rising interest in their use for human food [

50]. In conclusion, peat remains the most critical resource regarding fossil depletion and its contribution to climate change. Its partial replacement with locally sourced organic by-products can significantly mitigate this impact without harming other categories. A combined evaluation of environmental performance, economic viability, and material availability positions WF as the most immediately feasible solution, CS as an innovative alternative with high potential [

51], and BSG as the most environmentally beneficial option, albeit limited by competition with existing uses.

The observed differences among GM may be partly linked to the intrinsic agronomic properties of the by-products. WF primarily enhances aeration and porosity, improving root respiration and the water–air balance. CS contributes minerals and bioactive compounds that may exert mild biostimulant effects on growth. BSG supplies organic nitrogen and structural fibers, potentially increasing nutrient availability and GM stability. These mechanisms, although not directly evaluated here, offer a plausible explanation for the improved plant performance observed [

52]. These differences in supply and existing uses influence how quickly each material can be adopted in nursery practice. Materials that are supported and well-established in processing and distribution chains can be introduced more easily, while those with more limited or variable availability require gradual integration. Considering these aspects helps interpret which substitution paths may be more feasible in different production contexts [

45].

5. Conclusions

The analysis confirmed that peat is the main hotspot in nursery systems with regard to fossil resource depletion and climate change contribution. Its partial replacement with locally available organic by-products therefore emerges as a practical strategy to reduce environmental impacts without affecting other impact categories. Incorporating environmental outcomes into the economic assessment reveals that replacement levels of 20–40% can already enhance overall sustainability by lowering fossil fuel use and increasing economic returns. Addressing the research question, BSG40 and CS40 recorded the lowest eco-efficiency ratios, demonstrating the best GM.

CS20, BSG20, and WF40 rank next in eco-efficiency. These results reinforce the idea that adopting alternative GM is not only an ecological benefit but also a competitive advantage for the ornamental nursery industry. An additional point concerns by-product availability: wood fiber is immediately usable, coffee silverskin offers potential high circularity, and brewers’ spent grain is the most environmentally friendly but faces limitations due to competition with its traditional use as animal feed. Diversifying sources of substitution, tailored to specific production and local conditions, may be crucial for overcoming logistical and market barriers. Overall, the findings suggest that partially replacing peat with local by-products should be seen not merely as a short-term solution but as part of the environmental transition in the nursery sector.

Beyond the specific outcomes obtained in this trial, the integrated use of LCA and eco-efficiency also provides nurseries with a practical framework for evaluating future substrate options. This type of combined assessment can support strategic decisions related to certification requirements, procurement policies, and long-term planning, especially as the sector progressively moves toward lower-impact materials. In this regard, the approach may help growers identify substitution pathways that are technically feasible, economically acceptable, and aligned with emerging sustainability standards. Although these findings were obtained on Salvia ‘Amistad’, they are largely transferable to other potted ornamentals, as the reduction in fossil resource depletion depends mainly on the intrinsic impact of peat rather than on species-specific responses. However, agronomic performance may vary according to crop traits and production conditions, suggesting that optimal substitution rates should be validated across species and cultivation environments. The robustness of the environmental benefits supports the broader applicability of partial peat replacement within ornamental nursery systems. From a practical point of view, the results indicate that peat reduction can be introduced without altering the general organization of the production cycle. Partial replacement offers a simple way to reduce dependence on fossil-based materials while maintaining the value of the final product. A gradual introduction of these materials may support a smoother transition. Using components with a stable supply first and integrating those linked to local by-product streams when conditions allow can help manage fluctuations in availability and quality while still reducing peat use.

Future research should explore long-term agronomic performance, evaluate the availability of by-product flows, and develop integrated supply chains to enable their recovery and large-scale use.